Bayt Nattif

Bayt Nattif or Beit Nattif (Arabic: بيت نتّيف, Hebrew: בית נטיף and בית נתיף alternatively) was a Palestinian Arab village, located some 20 kilometers (straight line distance) southwest of Jerusalem, midway on the ancient Roman road between Beit Guvrin and Jerusalem, and 21 km northwest of Hebron.[4]

Bayt Nattif بيت نتّيف | |

|---|---|

Bayt Nattif 1948 | |

| Etymology: The house of Nettif[1] | |

Bayt Nattif | |

| Coordinates: 31°41′44″N 34°59′46″E | |

| Palestine grid | 149/122 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Hebron |

| Date of depopulation | October 21, 1948[2] |

| Population (1945) | |

| • Total | 2,150 |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Military assault by Yishuv forces |

| Current Localities | Netiv HaLamed-Heh,[3] Aviezer,[3] Neve Michael[3] |

In Roman times the town was known as Bethletepha, and commonly known by its Greek equivalent, Bethletephon.[5][6] The original Arabic version of the name was Bayt Lettif.[7]

The village lay nestled on a hilltop, surrounded by olive groves and almonds, with woodlands of oak and carobs overlooking Wadi es-Sunt (the Elah Valley) to its south.[4] It contained several shrines, including a notable one dedicated to al-Shaykh Ibrahim.[4] Roughly a dozen khirbas lay in the vicinity.[4]

During the British Mandate it was part of the Hebron Subdistrict. Bayt Nattif was depopulated during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War on October 21, 1948 under Operation Ha-Har.[4]

History

Roman and Byzantine periods (63 BCE - 6th century CE)

Bayt Nattif stood on the much-traveled ancient road connecting Eleutheropolis (Beit Guvrin) with Jerusalem, about midway between the two towns.[8]

The city had been assigned the status of toparchy, one of eleven toparchies or prefectures in Judaea given certain administrative responsibilities, known in classical sources by the name Betholetepha.[9][10]

According to Josephus, the city was sacked under Vespasian and Titus, during the first Jewish uprising against Rome.[11] During the 12th year of the reign of Nero, when the Roman army had suffered a great defeat under Cestius Gallus, with more than five-thousand foot soldiers killed, the people of the surrounding countryside feared reprisals from the Roman army and made haste to appoint generals and to fortify their cities. Generals were at that time appointed for Idumea, namely, over the entire region immediately south and south-west of Jerusalem, and which incorporated within it the towns of Bethletephon, Betaris, Kefar Tobah, Adurim, and Maresha. This region was called Idumea by the Romans on account of it being inhabited largely by the descendants of Esau (Edom) who became proselytes to Judaism during the time of John Hyrcanus.[12]

Ottoman period (1517 – 1917)

In 1596, Bayt Nattif was listed among villages belonging to the nahiya Quds, in the administrative district Liwā` of Jerusalem, in a tax ledger of the "countries of Syria" (wilāyat aš-Šām) and which lands were then under Ottoman rule. During that year, Bayt Nattif was inhabited by 94 households and 10 bachelors, all Muslim. The Ottoman authority levied a 33.3% taxation on agricultural products produced by the villagers (primarily on wheat, barley, olives, sesame seeds and grapes, among other fruits), besides a marriage tax and supplement tax on goats and beehives. Total revenues accruing from the village of Bayt Nattif for that year amounted to 12,000 akçe.[13][14]

In 1838 Edward Robinson visited, and remarks that their party was very well received by the villagers. He further noted that the villagers belonged to the "Keis" faction.[15][16] By the mid-19th century, a rift had divided families in the region over control of the district Bani Hasan, until at length it broke out into actual fighting between the Keis (Qays) faction, on the one side, and the Yaman faction, on the other.[17] Meron Benvenisti, writing of this period, says that Sheikh 'Utham al-Lahham waged "a bloody war against Sheikh Mustafa Abu Ghosh, whose capital and fortified seat was in the village of Suba."[18][19] In 1855, Mohammad Atallah in Bayt Nattif, a cousin of 'Utham al-Lahham, contested his rule over the region. In order to win support from Abu Ghosh, Mohammad Atallah gave his allegiance to the Yaman faction. This is said to have enraged 'Utham al-Lahham. He raised a fighting force and fell on Bayt Nattif on 3 January 1855. The village lost 21 dead. According to an eyewitness description by the horrified British consul, James Finn, their corpses were terribly mutilated.[20][21]

In 1863 Victor Guérin visited twice. The first time he visited he estimated that the village contained about one thousand inhabitants. He further noted that the houses were crudely built, one of them, which was assigned to the reception of foreigners, the al-Medhafeh, was a square tower. Above the entrance of the al-Medhafeh was a large block for lintel, featuring elegant mouldings, Guérin assumed it came from an ancient destroyed monument. Many other ancient stones were embedded here and there in private homes. Two wells, several cisterns and a number of silos and stores carved in the rock, and in continued use, were also ancient.[22][23]

Socin, citing an official Ottoman village list compiled around 1870, noted that Bayt Nattif had 66 houses and a population of 231, though the population count included men only.[24] Hartmann found that Bayt Nattif had 120 houses.[25]

In 1883, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine described Bayt Nattif as being "a village of fair size, standing high on a flat-topped ridge between two broad valleys. On the south, about 400 feet below, is a spring (`Ain el Kezbeh), and on the north a rock-cut tomb was found. There are fine olive-groves round the place, and the open valleys are very fertile in corn."[26]

Around 1896 the population of Bayt Nattif was estimated to be about 672 persons.[27]

British Mandate (1917 – 1948)

For all practical purposes, the British inherited from their Turkish counterparts the existing laws in regard to land tenures as defined in the Ottoman Land Code, to which laws there was later added subsidiary legislation.[28] At the time of the British occupation the land tax was collected at the rate of 12.5% of the gross yield of the land. Crops were assessed on the threshing floor or in the field and the tithe was collected from the cultivators.[29] In 1925, additional legislation provided that taxation on crops and other produce not exceed 10%. In 1928, as a measure of reform, the Mandate Government of Palestine began to apply an Ordinance for the "Commutation of Tithes," this tax in effect being a fixed aggregate amount paid annually. It was related to the average amount of tithe (tax) that had been paid by the village during the four years immediately preceding the application of the Ordinance to it.[30]

In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Bayt Nattif had a population of 1,112, all Muslims,[31] increasing in the 1931 census to 1,649, still all Muslim, in a total of 329 houses (which figure includes houses built in the nearby ruin, Khirbet Umm al-Ra’us).[32]

In 1926, some 259 dunums (61.77 acres) of land near Beit Nattif were designated as "Jabal es-Sira Forest Reserve no. 73," held by the State.[33]

In 1934, Dimitri Baramki of the Mandate Department of Antiquities directed the excavation of two cisterns in the village of Bayt Nattif which produced mostly ceramic ware dating from between the 1st and 3rd centuries CE.[4]

By the 1945 statistics, the population had increased to 2,150 Muslims.[34][35] In 1944/45, a total of 20,149 dunums were allocated to cereal grains in the adjacent lowlands; 688 dunums were irrigated or used for orchards,[36] while 162 dunams were built-up (urban) areas.[37]

1948 war and depopulation

In the proposed 1947 UN Partition Plan, it was designated as part of the Arab state.[38]

As hostilities broke out in the wake of the publication of the plan, Yohanan Reiner and Fritz Eisenstadt, military advisors of David Ben-Gurion proposed, on December 18, 1947, that any Arab attack be met with a decisive blow, consisting of the "destruction of the place or chasing out the inhabitants and taking their place." Such proposals were mulled and shelved - one participant likening such proposals to the destruction of Lidice - but in January 1948, a Jerusalem District HQ document entitled "Lines of Planning for Area Campaigns for the Month of February 1948," foresaw taking steps to secure the Jerusalem-Tel Aviv route. In this document one measure consisted of "the destruction of villages or objects dominating our settlements or threatening our lines of transportation," and among the objectives of the plan the destruction of the southern bloc of Beit Nattif was envisaged.[39][40]

The official Jewish account (The "History of Haganah") alleges that the village of Bayt Nattif took part in the killing of thirty-five Jewish fighters (see the Convoy of 35, the "Lamed-Heh") who were en route with supplies to the besieged block of kibbutzim of Gush Etzion, on January 16, 1948. However, reports from the New York Times correspondent indicate that the convoy took a wrong turn, and ended up in Surif. The Arab version is that the convoy had attacked Surif deliberately, and had held it for an hour before being driven out. After this, the Haganah mounted a "punitive" attack on Bayt Nattif, Dayr Aban and Az-Zakariyya.[3] In late January 1948, the Haganah's Jerusalem HQ suggested "the destruction of the southern block of Bayt Nattif" in order to secure transportation along the Tel-Aviv-Jerusalem highway.[41]

The Israeli Air Force bombed the area of Bayt Nattif on October 19, 1948, which started panic flights from Bayt Nattif and Bayt Jibrin.[42] Bayt Nattif was depopulated during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War on October 21, 1948 under Operation Ha-Har, by the Fourth Battalion of the Har'el Brigade.[4][43][44] There are conflicting reports about its conquest, one Palmach report says that the villagers "fled for their lives",[45] while a Haganah report says that the village was occupied "after some light resistance."[4]

During late 1948, the IDF continued to destroy conquered Arab villages, in order to block the villagers return.[46] Among these destroyed villages was Bayt Nattif which, based on Jewish sources, was completely destroyed as a punitive measure for the village's involvement in the detection and massacre of the Convoy of the thirty-five.[47] There are also conflicting reports about which other villages were destroyed with it; one report says that Dayr Aban was destroyed with it,[46] while another report says that Dayr al-Hawa was destroyed with it.[45]

On 5 November, the Harel Brigade raided the area south of Bayt Nattif, driving out any Palestinian refugee they could find.[48]

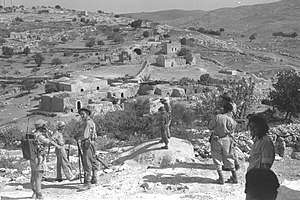

Harel Brigade clearing Bayt Nattif. 1948

Harel Brigade clearing Bayt Nattif. 1948 5th Battalion, Harel Brigade in Bayt Nattif, 1948

5th Battalion, Harel Brigade in Bayt Nattif, 1948 Houses being demolished by the Harel Brigade. Bayt Nattif, 1948

Houses being demolished by the Harel Brigade. Bayt Nattif, 1948 Bayt Nattif during demolition by the Harel Brigade, 1948

Bayt Nattif during demolition by the Harel Brigade, 1948 Members of the Yiftach Brigade in Bayt Nattif. 1948

Members of the Yiftach Brigade in Bayt Nattif. 1948

Israeli rule since 1948

Netiv HaLamed-Heh was built on village land in 1949, while Aviezer and Neve Michael were built on village land in 1958.[3] After the Arab-Israeli War of 1948, the ruin of Bayt Nattif remained under Israeli control under the terms of the 1949 Armistice Agreement[49] between Israel and Jordan, until such time that the agreement was dissolved in 1967.[50][51]

Today, the land whereon was once built Bayt Nattif comprises what is now called The Forest of the Thirty-Five (Hebrew: יַעֲר הַל"ה) and is maintained by the Jewish National Fund. Erik Ader, former Dutch ambassador to Norway, whose father Bastiaan Jan Ader is memorialized in the forest as one of the Righteous Among the Nations for saving 200 Jews from the Holocaust, has asked that his father's name be removed as a protest against what Ader called "the ethnic cleansing" of Palestinians. In response, the Jewish National Fund expressed its respect for the actions of Ader’s parents, stating that the monument was legally constructed on state-owned lands.[52][53]

Archaeology

Based upon archaeological finds that were discovered in Bayt Nattif, the city was still an important site in the Late Roman period. The place was now inhabited by Roman citizens and veterans, who settled the region as part of the Romanization process that took place in the rural areas of Judaea after the Bar Kokhba revolt.[54]

In 2013, archaeological survey-excavations of Bayt Nattif were conducted by Yitzhak Paz and Elena Kogan-Zahavi on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA), and by Boaz Gross on behalf of Tel-Aviv University's Institute of Archaeology.[55] In 2014, eight separate surveys were conducted on the site.[56]

The "Beit Nattif lamp"[57] is a type of ceramic oil lamp that was recovered during the archaeological excavation of two cisterns at the site.[58] Some of them were decorated with a depiction of the Temple Menorah.[59] Based on the discovery of unused oil lamps and molds, it is believed that during the late Roman or Byzantine period the village manufactured pottery, possibly selling its wares in Jerusalem and Beit Guvrin.[60] During a 2014 dig at Khirbet Shumeila, 1 km north of Beit Nattif, stone molds for 3rd-4th century "Beit Nattif lamps" were found within the remains of a large villa.[61]

A Roman milestone dated 162 CE was discovered 3/4 km southeast of Bayt Nattif showing the distance from Jerusalem and bearing the following Latin and Greek inscription:[62][63]

- lmp(erator) Caesar M(arcus) Aurelius Antoninus Aug(ustus) pont(ifex) max(imus) trib(unicaiae) potest(atis) XVI co(n)s(ul) III et Imp(erator) Caesar L(ucius) Aurelius Uerus trib(uniciae) potest(atis) II co(n)s(ul) II [diui Anton]ini fili diui Traia[ni Par]thici [pronepotes] diui [Neru]ae abnepotes

- [ἀπὁ Κ]ολωνίας Αἰλ(ίας) μέχρι ὦδε μίλι(α) lH

A mosaic pavement, probably belonging to a church has been excavated at Bayt Nattif. The type of mosaic found are usually dated to the 5th and the 6th century CE.[64]

Gallery

Razed structure at Bayt Nattif

Razed structure at Bayt Nattif Mouth of cistern near Bayt Nattif

Mouth of cistern near Bayt Nattif General view of Bayt Nattif, looking south toward the Elah Valley

General view of Bayt Nattif, looking south toward the Elah Valley Carob tree on the ascent to Bayt Nattif

Carob tree on the ascent to Bayt Nattif Mouth of cistern in Bayt Nattif

Mouth of cistern in Bayt Nattif Old cistern with secure stone cover

Old cistern with secure stone cover Carved steps along ancient Roman road, adjacent to regional hwy 375 in Israel (near Bayt Nattif)

Carved steps along ancient Roman road, adjacent to regional hwy 375 in Israel (near Bayt Nattif) Old road in Bayt Nattif, lined with field stones

Old road in Bayt Nattif, lined with field stones Tombs at Bayt Nattif

Tombs at Bayt Nattif Wine press carved in rock at Bayt Nattif

Wine press carved in rock at Bayt Nattif Walled structure at Bayt Nattif

Walled structure at Bayt Nattif

References

- Palmer, 1881, p. 286

- Morris, 2004, p. xx, village #342. Also gives cause of depopulation.

- Khalidi, 1992, p. 212

- Khalidi, 1992, pp. 211-212.

- Emil Schürer and Fergus Millar, The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ: 175 B.C.-A.D. 135, Volume III Part 2, Bloomsbury 2000, p. 910

- Tsafrir, Di Segni and Green, 1994, p. 84

- In an interview with Muhammad Abu Halawa (born 1929), he disclosed unto his interviewer, Rakan Mahmoud, in 2009, that the original name of the village was Bayt Lettif, but since it was phonetically easier for the tongue to say Bayt Nattif, so did the name change. See Palestine Oral History: Interview with Muhammad Halawa #1, Bayt Nattif-Hebron, Arabic (In video: 2:48 – 2:56)

- Geggel, Laura (9 March 2017). "Ancient Route Connected to Roman 'Emperor's Road' Unearthed in Israel". LiveScience.com (via Yahoo.com). Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- Petersen (2001), pp. 125–126

- The 11 were: 1) The toparchy of Gophna; 2) The toparchy of Acrabatta; 3) The toparchy of Thamna; 4) The toparchy of Lydda; 5) The toparchy of Emmaus; 6) The toparchy of Pella; 7) The toparchy of Idumea, one of whose principal cities being Bethletephon; 8) The toparchy of En Gedi; 9) The toparchy of Herodium; 10) The toparchy of Jericho, and 11) The toparchy of Jamnia and Joppa. These all answered to Jerusalem.Josephus, De Bello Judaico (The Jewish War), 3.3.4

- Josephus, De Bello Judaico (The Jewish War) 4.8.1.

- Josephus, De Bello Judaico (The Jewish War), 2.20.3-4

- Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 114

- Toledano, 1984, p. 290, gives the position of 34°59′20″E 31°41′45″N

- Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 2, pp. 341-347

- Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, p. 16

- Schölch, 1993, p. 229

- Benvenisti, 2002, in a chapter named "The Convenience of the Crusades", p. 301

- Schölch, 1993, p. 231

- Schölch, 1993, p. 232

- Finn, 1878, vol 2, pp. 194-210

- Guérin, 1869, pt. 2, pp. 374-377

- Guérin, 1869, pt. 3, pp. 329-330

- Socin, 1879, p. 147

- Hartmann, 1883, p. 145

- Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p. 24

- Schick, 1896, p. 123

- A Survey of Palestine (Prepared in December 1945 and January 1946 for the information of the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry), chapter 8, section 5, British Mandate Government of Palestine: Jerusalem 1946, p. 255

- A Survey of Palestine (Prepared in December 1945 and January 1946 for the information of the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry), chapter 8, section 4, British Mandate Government of Palestine: Jerusalem 1946, p. 246

- A Survey of Palestine (Prepared in December 1945 and January 1946 for the information of the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry), chapter 8, section 4, British Mandate Government of Palestine: Jerusalem 1946, pp. 246 – 247

- Barron, 1923, Table V, Sub-district of Hebron, p. 10

- Mills, 1932, p. 28

- May 1939, Office of the Commissioner for Lands and Surveys, Jerusalem, Conservator of Forest, Government of Palestine (Department of Forests)

- Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 23

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 50

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 93

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 143

- "Map of UN Partition Plan". United Nations. Archived from the original on 24 January 2009.

- Benny Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee problem Recvisited, Cambridge University Press 2004 pp.73-74.

- Gerard Michaud,'A matter of choice:Palestinians say they wouldn't necessarily exercise the 'right of return,' Jerusalem Post 7 February 2008

- Morris, 2004, p. 74

- Morris, 2004, p. 468, note #32 in Morris, 2004, p. 494

- Morris, 2008, p. 329

- Morris, 2004, p. 462

- Morris, 2004, p. 466 note #14, in Morris, 2004, p. 493. "Book of the Palmah, II" pp. 646, 652

- Morris, 2004, p. 355, footnote #85, on Morris, 2004, p. 400: Harel Brigade HQ, "Daily report for 22 October", 23 Oct. 1948, IDFA 4775\49\3, for the destruction of Bait Nattiv and Deir Aban

- Har’el: Palmach brigade in Jerusalem, Zvi Dror (ed. Nathan Shoḥam), Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishers: Benei Barak 2005, p. 270 (Hebrew)

- Morris, 2004, p. 518

- The 1949 Armistice Agreement between Israel and Jordan

- Enlarged map showing Bayt Nattif (Beit Nattif) in relation to the "Green-Line"

- Larger map showing "1949 Cease-fire line" (Green-line) between Israel and Jordan (Hebrew)

- Cnaan Liphshiz, Gentile’s Son Wants Name Pulled From Razed Palestinian Village,' The Forward 22 November 2016.

- England, Charlotte Man whose father saved Jews from Nazis asks Israel to take his name off 'ethnic cleansing' memorial The Independent 23 November 2016

- Zissu and Klein, 2011, A Rock-Cut Burial Cave from the Roman Period at Beit Nattif, Judaean Foothills Archived 2014-08-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Israel Antiquities Authority, Excavators and Excavations Permit for Year 2013, Survey Permits # A-6696 and # B-400

- Zubair Adawi and Yitzhak Paz conducted archaeological research in one area (Israel Antiquities Authority, Excavators and Excavations Permit for Year 2014, Survey Permit # A-7002), while another was conducted by Daniel Ein-Mor and Yitzhak Paz (Israel Antiquities Authority, Survey Permit # A-7003), another by Ron Lavi and Yitzhak Paz (Israel Antiquities Authority, Survey Permit # A-7049), another by Natalia German and Yitzhak Paz (Israel Antiquities Authority, Survey Permit # A-7097), and others conducted by Mizrahi Sivan and Yitzhak Paz (Israel Antiquities Authority, Survey Permit # A-7261), by Elena Kogan-Zahavi and Yitzhak Paz (Israel Antiquities Authority, Survey Permit # A-7263), and by Boaz Gross and Tamar Harpak on behalf of Tel-Aviv University's Institute of Archaeology (Israel Antiquities Authority, Survey Permits # B-412 and # B-416).

- "Judean Beit Nattif Oil Lamp". Archived from the original on 2014-02-03. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- New light on daily life at Beth Shean

- Eisenbud, Daniel K. (January 3, 2017). "HIKERS FIND SECOND TEMPLE PERIOD ENGRAVINGS OF MENORAH IN JUDEAN SHEPHELAH CISTERN". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- Jerusalem Ceramic Chronology: Circa 200-800 CE, Jodi Magness

- http://www.lightingsibiu.eu/ila-speaker/benyamin-storchan/ Benyamin Storchan, A New Light on the "Beit Nattif" Lamp., Abstract

- See pp. 80–81 (§ 288) in: Thomsen, Peter (1917). "Die römischen Meilensteine der Provinzen Syria, Arabia und Palaestina". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 40 (1/2): 1–103. JSTOR 27929302. Mentioned also by Clermont-Ganneau in Archaeological Researches in Palestine During the Years 1873–1874, vol. 1, Palestine Exploration Fund: London 1899, p. 470 (note 3).

- Ze'ev Safrai, Boundaries and Administration (גבולות ושלטון בארץ ישראל בתקופת המשנה והתלמוד), Ha-kibbiutz Ha-meuchad: Tel-Aviv 1980, p. 89 (Hebrew)

- Baramki, 1935, pp. 119–121

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bayt Nattif. |

Bibliography

- Baramki, D.C. (1935). "Recent Discoveries of Byzantine Remains in Palestine. A Mosaic Pavement at Beit Nattif". Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities in Palestine. 4: 119–121.

- Baramki, D.C. (1936). "Two Roman Cisterns at Beit Nattif". Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities in Palestine. 5: 3–10.

- Barron, J. B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Benvenisti, M. (2002). Sacred Landscape: The Buried History of the Holy Land Since 1948. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23422-2.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. (p. 52)

- Dauphin, Claudine (1998). La Palestine byzantine, Peuplement et Populations. BAR International Series 726 (in French). III : Catalogue. Oxford: Archeopress. ISBN 0-860549-05-4. (p. 918)

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Finn, J. (1878). E.A. Finn (ed.). Stirring Times, or, Records from Jerusalem Consular Chronicles of 1853 to 1856. Edited and Compiled by His Widow E. A. Finn. With a Preface by the Viscountess Strangford. 2. London: C.K. Paul & co.

- Guérin, V. (1869). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 1: Judée, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie nationale.

- Guérin, V. (1869). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 1: Judée, pt. 3. Paris: L'Imprimerie nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Josephus, De Bello Judaico (The Jewish War), Translated by William Whiston, A.M. Auburn and Buffalo. John E. Beardsley. 1895

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All that Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington DC: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Morris, B. (2008). 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War. Yale University Press. ISBN 1-902210-67-0.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Petersen, Andrew (2001). A Gazetteer of Buildings in Muslim Palestine (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology). I. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-727011-0.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 2. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Schick, C. (1896). "Zur Einwohnerzahl des Bezirks Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 19: 120–127.

- Schölch, Alexander (1993). Palestine in Transformation, 1856-1882: Studies in Social, Economic, and Political Development. Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-234-2.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

- Toledano, E. (1984). "The Sanjaq of Jerusalem in the Sixteenth Century: Aspects of Topography and Population". Archivum Ottomanicum. 9: 279–319.

- Tsafrir, Y.; Leah Di Segni; Judith Green (1994). (TIR): Tabula Imperii Romani: Judaea, Palaestina. Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities. ISBN 965-208-107-8.

- Zissu, Boaz; Klein, Eitan (2011). "A Rock-Cut Burial Cave from the Roman Period at Beit Nattif, Judaean Foothills" (PDF). Israel Exploration Journal. 61 (2): 196–216. Archived from the original on 2015-12-07.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

External links

- Horbat Bet Natif - Israel Antiquities Authority

- Welcome To Bayt Nattif

- Bayt Nattif, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, 1880 Map, Map 17: IAA, Wikimedia commons Coordinates: East longitude, 34.59; North latitude, 31.41

- Bayt Nattif, Palestine Family.net