Mosaic of Rehob

The Mosaic of Reḥob, also known as the Tel Rehov inscription and Baraita of the Boundaries, is a late 3rd–6th century CE[2] mosaic discovered in 1973, inlaid in the floor of the foyer or narthex of an ancient synagogue near Tel Rehov,[3][4] 4.5 kilometers (2.8 mi) south of Beit She'an and about 6.5 kilometres (4.0 mi) west of the Jordan River, containing the longest written text hitherto discovered in any mosaic in the Land of Israel, and also the oldest known Talmudic text.[5]

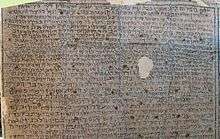

Mosaic of Rehob, 6th-century Talmudic text (click to enlarge) | |

Shown within Mandatory Palestine  Mosaic of Rehob (Israel) | |

| Alternative name | Inscription of Tel Rehov |

|---|---|

| Location | Tell el-Farwana (Khirbet Farwana), Israel |

| Region | Beit She'an, Israel |

| Coordinates | 32°27′47″N 35°29′37″E |

| Type | Mosaic |

| Part of | Synagogue |

| Area | 4.30 by 2.75 metres (14.1 ft × 9.0 ft) |

| History | |

| Founded | ca. late 3rd century CE[1] |

| Abandoned | 7th century CE |

| Periods | Roman to Byzantine |

| Cultures | Byzantine |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1973 |

| Archaeologists | Yaakov Sussmann, Shaul Lieberman, Fanny Vitto |

| Condition | Good (although removed from locale) |

| Ownership | Israel Museum |

| Public access | Yes, both to the museum and to the open field with scarce remains |

| Website | www |

Unlike other mosaics found in the region, the Reḥob mosaic has very little in the form of ornate design and symmetric patterns, but is unique due to its inscription, acclaimed by scholars to be one of the most important epigraphical findings discovered in Israel in the last century.[6] Its text sheds invaluable light on the historical geography (toponymy) of Palestine during the Late Roman and Byzantine periods, as well as on Jewish and non-Jewish ethnographic divisions in Palestine for the same periods and their relation to one another, specifically, on agricultural produce cultivated by farmers, and the extent of Jewish law regulating the use of such farm products grown in different regions.[7] These eight regions are: the area of Scythopolis (modern-day Beit She'an) and the Jordan valley (the longest paragraph), Susita (Hippos) and its neighbouring settlements on the east bank of the Sea of Galilee, Naveh (Nawā) in the Roman province of Arabia Petraea, Tyre and its neighbouring cities to the south, and the Land of Israel proper, dealt with in the second-longest paragraph, followed by the cities of Paneas and Caesarea, finishing with villages from the vicinity of Sebaste.[8]

By delineating the boundaries of the Land of Israel, it seeks to establish the legal status of the country in its various parts from the time of Israel's return from the Babylonian captivity,[9][10] and whether or not local farm products acquired by Jews from other Jews, or from gentiles and Samaritans, are exempt or obligated in what concerns the laws of Seventh Year produce, and of demai produce. The mosaic also describes different kinds of fruits and vegetables that were cultivated in the country at the time, and the laws which applied to them at the time.[11]

History

A Late Roman and Byzantine-period Jewish village located about one kilometre (half mile) northwest of Tel Rehov has preserved the old name in the form of Rehov (Hebrew) or Roob/Roōb (Latin).[12][13][14]

According to excavator F. Vitto, the village synagogue underwent three phases of construction and reconstruction: first built as a basilical hall in the 4th century CE, it was destroyed by a fire and rebuilt in the following century, with the addition of a bemah, of a new mosaic floor and a plaster coating for the walls and pillars, decorated with several inscriptions; and the last phase, dating to the 6th or 7th century CE, when the narthex was added on whose floor the halakhic inscription was laid.[8] Others put the creation of the halakhic inscription in the late 3rd century CE at the earliest.[15] The synagogue was probably abandoned after being destroyed in an earthquake.[16]

The site of the ancient Jewish village was later taken by the Arab village of Farwana, documented at least since the Ottoman period, and abandoned during the 1948 war. Kibbutz Ein HaNetziv was established in 1946 on land including the ancient site.[17]

The remains of the ancient synagogue were first discovered by members of Kibbutz Ein HaNetziv while preparing their lands for cultivation in the late 1960s. An archaeological excavation of the site in 1973, led by a team under IAA's Fanny Vitto, revealed the mosaic and its content, which is now on display at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.[18]

Description of mosaic

The mosaic pieces are made of black limestone tesserae contrasted against a white background, measuring 4.30 by 2.75 metres (14.1 ft × 9.0 ft), with an accompanying text written on 29 lines, comprising a total of 350 words,[19] with an average length of 4 metres (13 ft) to each line. It begins with the salutation, "Shalom" – Peace!, followed by a long halakhic text, and ends with the salutation, "Shalom," followed by an appendix where it lists some eighteen towns in the vicinity of Sebaste (the ancient city of Samaria) whose fruits and vegetables were exempt from tithes and the stringencies applied to Seventh Year produce. There is little uniformity in the size of the letters, while the spelling of some words is faulty. Portions of the main text contain elements that are related to late second-century rabbinic literature, particularly that found in the Tosefta (Shevi'it 4:8–11), the Jerusalem Talmud (Demai 2:1; Shevi'it 6:1) and Sifrei on Deuteronomy 11:24, although the mosaic of Reḥob expands on aspects of each. The more ancient text in the Reḥob mosaic has been used to correct errors in transmission of extant rabbinic texts.[20]

Legal (halakhic) background

The text in the Reḥob mosaic can only be understood in the context of Jewish law at the time, which required the tithing of agricultural produce six years out of a seven-year cycle, as well as the observance of Seventh Year law strictures on the same produce once in every seven years. This, too, was contingent upon lands that had been settled by returning Jews from the Babylonian captivity. The underlying principle in Jewish law states that when the Jewish exiles returned from the Babylonian captivity in the 4th century BCE, the extent of territories resettled by them in Galilee and in Judea did not equal nor exceed the territory originally conquered by Israel at the time of Joshua, more commonly referred to as "those who came-up from Egypt."[21] The practical bearing of this restructuring of boundaries (although still part of the biblical Land of Israel proper)[22] meant that places then settled by non-Jewish residents in the land (whether Phoenicians, Syrians, Grecians, or otherwise) and not taken by Israel were not deemed as consecrated land[23] and, therefore, fruits and vegetables grown in such places and purchased by Jews were exempt from the laws of tithing, and of Seventh Year restrictions. However, if fruits and vegetables were purchased by gentile vendors from Israelites in their respective places and transported into these non-consecrated places in order to be sold in the marketplaces, they were still made subject to tithing as demai-produce by prospective Jewish buyers.[24] The fruits and vegetables mentioned in the Reḥob mosaic with respect to Beit She'an (as detailed in the Jerusalem Talmud) were not locally grown in Beit She'an, but were transported there from places settled by Israel.[25] Beit She'an was a frontier city along the country's eastern front with Transjordan, and since it was not initially settled by Israelites upon their return from Babylon, although later Israelites had joined the local inhabitants,[26] all home-grown fruits and vegetables there were made exempt from tithing in the days of Rabbi Judah HaNasi.[27]

Translation of ancient text

Shalom. These fruits are forbidden in Beit She'an during the Seventh Year, but during other years of the seven-year cycle they are tithed as demai-produce: cucumbers,[28] watermelons, muskmelons,[29] parsnip (carrots),[30] mint that is bound by itself,[31] black-eyed peas[32] that are bound with rush,[33] wild leeks[34] between Shavuot and Hanukkah,[35] the seed kernels,[36] black cumin,[37] sesame, mustard, rice, cumin, dried lupines,[38] large-sized peas[39] that are sold by measure, garlic, scallions[40] of the city that are sold by measure, grape hyacinths,[41] late-ripening dates,[42] wine, [olive] oil, on the Seventh Year the seventh-year laws apply [to them]; on the [other] years of the seven-year cycle, they are tithed as demai-produce, and [if there was] a loaf of bread, the Dough portion (Heb. ḥallah) is always [separated from it].[43][44]

[Excursus: The agricultural products named above were not cultivated in Beit She'an, but were brought into the city by donkey drivers, whether they were Jewish rustics or in some cases non-Jews, who had bought them from Jewish planters in other regions of the country[45] to be sold in the marketplace of Beit She'an.[46] To this list can be added the special fruits peculiar to the Hebrew nation and mentioned in Mishnah Demai 2:1, if perchance they were acquired by a Jew from his fellow co-religionist who was unskillful in the laws of his countymen, such as a cultivar of dates grown only in Israel,[47] cakes of dried figs that were prepared strictly in Israel, and carob-fruit of a quality found only in Israel. In this case, they too would require the removal of the tithe known as demai. All other fruits and vegetables cultivated in Beit She'an would have been exempt from tithing altogether, seeing that when Rabbi Judah HaNasi permitted the eating of vegetables in the Seventh Year in Beit She'an,[48] it was one and the same enactment, namely, the release from the Seventh Year obligations and the release from tithing all produce throughout the remaining six years of the seven-year cycle.[49]]

These are the places that are permitted in the vicinity of Beit She'an:[50] southward, that is to say, [from] the Gate of Ḳumpōn[51] extending as far as the White Field;[52] from the west, that is to say, [from] the Gate of Zayara extending as far as the end of the pavement; from the north, that is to say, the Gate of Sakkūtha extending as far as Kefar Ḳarnos,[53] while Kefar Ḳarnos [itself] is deemed as Beit She'an;[54] and from the east, that is to say, the Gate of the Dung-spreaders[55] extending as far as the monument of Fannuqatiah,[56] while the Gate of Kefar Zimrin and the Gate of the marshland,[57] in those places that are within the gate, [what is grown] is permitted, but beyond [the gate without, what is grown] is prohibited.[58] The towns that are prohibited in the region of Sussitha (Hippos)[59] [are as follows]: 'Ayyanosh,[60] 'Ain-Ḥura,[61] Dambar, 'Ayūn,[62] Ya'arūṭ,[63] Kefar Yaḥrīb,[64] Nob,[65][66] Ḥisfiyyah,[67] Kefar Ṣemaḥ; now the Rabbi (Judah HaNasi) permitted Kefar Ṣemaḥ.[68] The towns that are of a dubious nature in the region of Naveh[69] [are as follows]: Ṣeir,[70] Ṣayyer,[71] Gashmai,[72] Zayzūn,[73] Renab and its ruin,[74] Igorei Ḥoṭem,[75] and the fortified city (kerakh) of the son of Harag.[44][76]

[Excursus: The import of detailing the above frontier towns and villages was to show the boundaries of the Land of Israel as retained by the Jews who returned from the Babylonian captivity. Where agricultural produce was prohibited unto Jews living in these areas, this implies that these places were originally part of those places settled by the Returnees from Babylon, and that since the land was consecrated by their arrival in those parts, all fruits and vegetables were prohibited until the time that they could be tithed, and the land was required to lie fallow during the Seventh Year. However, where the places were designated as "dubious," this is explained in the Tosefta (Shevi'it 4:8) as meaning that initially these places were permitted (as there was no requirement to tithe produce grown in these places), but later the Sages of Israel made all fruits and vegetables in these places prohibited until they were first tithed. This may have been the result of produce being brought into these towns and villages from regions liable to tithing and sold there, or else it was not clear unto the Sages if these places had actually been settled by the people of Israel who returned from Babylon. In any case, the practice is to behave stringently with regard to such produce.]

Regulation of produce between Achziv (Chezib) and Tyre

The maritime city of Akko (Ptolemais), and the river south of Achziv (Chezib),[77] a small coastal town ca. 15 kilometers (9.3 mi) north of Acre, according to the Mishnah (Demai 1:3 and Gittin 1:2), were the extent of the northern boundary settled by Jews returning from the Babylonian captivity in the days of Ezra.[78] Produce locally grown in the country beyond Achziv was exempt from the rules of demai-produce,[79] but if purchased from Achziv itself, it required tithing.[80] Although the towns and villages (in what follows here) were traditionally outside of the territorial bounds occupied by Jews returning from Babylonia, still, these cities attracted Jewish settlement.[81] In addition, fruits and vegetables grown in the Land of Israel were often transported northward, along the route known as the Promontory of Tyre (Heb. סולמות של צור). Israelites who frequented these areas, or who had moved there, were likely to buy fruits that had not been properly tithed in Israel, or had been marketed during the Sabbatical Year.[82] The emphasis on the regulation of agricultural produce obtained by Israel in the following northern areas, or, as the Rehob inscription says, "what an Israelite has purchased" in those parts, was because of its doubtful nature.

The towns that are prohibited in the region of Tyre [are as follows]: Shaṣat, Beṣet,[83] Pi Maṣūbah,[84] the Upper Ḥanūtha,[85] the Lower Ḥanūtha,[86] Bebarah,[87] Rosh Mayya,[88] 'Ammon,[89] Mazih which is the Castle,[90] and all which an Israelite has bought is prohibited.[91][44]

Boundary of the Land of Israel in the 4th c. BCE

The following frontier cities once marked the boundary of the Land of Israel, or the extent of places repopulated after the return from Babylonian exile. In a broader sense, the list of frontier towns and villages herein named represent the geographical limits of regulations imposed upon all agricultural produce, making them fully liable to tithing and to sabbatical-year restrictions within that same border, or, in the event of being purchased from the common people of the land, to separate therefrom only the demai-tithe. As one moved further east of Achziv, the border extended northward, into what are now portions of south Lebanon, and as far east as places in the present-day Kingdom of Jordan. While the settlements here named reflect a historical reality, bearing heavily on Jewish legal law (Halacha), they did not always reflect a political reality, insofar that the political borders have since changed owing to a long history of occupiers and conquerors.[92]

The boundaries of the Land of Israel, [that is to say], the place h[eld][93] by those returning from Babylonia, [are as follows]: The passage of Ashkelon,[94] the wall of Sharoshan Tower [of Caesarea],[95] Dor,[96] the wall of Akko, the source of the spring of Ǧiyāto[97] and Ǧiyāto itself,[98] Kabri[tha],[99] [B]eit Zanitha,[100] the Castle of Galilee,[101] Quba'ya of Ayata,[102] Mamṣi’ of Yarkhetha,[103] Miltha of Kurayim,[104] Saḥratha of Yatī[r],[105] [the riveri]ne brook of Baṣāl,[106] Beit 'Ayit,[107] Barashatha,[108] Awali of Battah,[109] the Gorge of 'Iyyon,[110] Massab Sefanḥa,[111] the walled city of B[ar-Sa]nnigora,[112] the Upper Rooster of Caesarion,[113] Beit Sabal,[114] Ḳanat,[115] Reḳam,[116] Trachonitis[117] [of] Zimra[118] which is in the region of Buṣrah,[119] Yanqah, Ḥeshbon,[120] the brook of Zered,[121] Igor Sahadutha,[122] Nimrin,[123] Melaḥ of Zayzah, Reḳam of Ǧayāh,[124] the Gardens of Ashkelon[125] and the great road that leads into the desert.[126] These are the fruits that are prohibited in Paneas[127] on the sabbatical-year,[128] but in the remaining years of the seven-year cycle they are tithed entirely as demai-produce: Rice, walnuts, sesame, black-eyed peas, [and] there are those who also say early ripening Damascene plums,[129] lo! These are [all] to be treated on the Seventh Year as seventh-year produce,[130] but in the remaining years of the seven-year cycle they are tithed as produce that has certainly been left untithed, and even [had they been brought] from the Upper Rooster[131] and beyond.[44]

[Excursus: Jose ben Joezer of Ẓareda and Jose ben Yoḥanan of Jerusalem decreed defilement in respect of the country of the gentiles (BT, Shabbat 14b), so that the priests of Aaron's lineage will not venture beyond the borders of Israel and, in so doing, become defiled unawares by corpse-uncleanness and turn again to defile their offerings (which must needs be eaten by them in a state of ritual purity). Ashkelon was long deemed as one of such cities, as it was settled by gentiles and not conquered by Israel upon their return from the Babylonian exile.[132] The Jerusalem Talmud (Shevi'it 6:1) relates how that Rabbi Phinehas ben Jair, a priest of Aaron's lineage, and others with him, used to go down into the marketplace of the Saracens in Ashkelon to buy wheat during the Seventh Year, and return to their own city, and immerse themselves in order to eat their bread (Terumah) in a state of ritual purity. The Beth-Din of Rabbi Ishmael, the son of Rabbi Jose, and Ben HaKapar, when they heard about what Rabbi Phinehas ben Jair had done, a most pious man on all other accounts, but who went down into Ashkelon when it was not permitted for priests to venture outside the Land of Israel, understood thereby that Ashkelon – though not conquered by those returning from the Babylonian exile – was not like other lands of the gentiles, and that defilement had not been decreed upon that city.[133] Therefore, taking as an exemplum the act they heard performed by Rabbi Phinehas ben Jair, they assembled themselves and reverted the old practice, decreeing a state of cleanness over the city's air, and that, henceforth, Jews (including those of the priestly stock) were permitted to go into the city without harboring feelings of guilt or fear of contracting uncleanness. The next day, they assembled themselves again, this time to declare, by a majority vote, that the city's agricultural produce was exempt from tithes – even with such doubtful produce as had been carried into the city from places in Israel proper, unlike the restrictions regarding produce brought into the region of Tyre.[134] This was done with the intent of easing the burden of the poor of Israel during the Seventh Year.[135]]

Caesarea Maritima

The maritime city of Caesarea Maritima was an enclave along the Mediterranean coast not immediately settled by Jewish émigrés returning from the Babylonian exile. Later, however, Jews joined the inhabitants of the city, yet, by the 1st century CE, it was still principally settled by foreigners, mostly Grecians.[136] To ease the strictures placed upon the poor of the Jewish nation during the Seventh Year (since planting was prohibited throughout that year, and after-growths could not be taken by the people), Rabbi Judah HaNasi (2nd century CE) found the juridical legitimacy to release the city (and its bounds) from the obligation of tithing locally-grown produce, and from the restrictions associated with Seventh Year produce.[137] Notwithstanding, on certain fruits and on one commodity spice (see infra.), they still required the separation of the demai tithe because of the majority of these specific items being transported into Caesarea from other places of the country held by Israel. However, during the Seventh Year, since these items were usually not harvested or worked by Jews in that year, the majority of such produce were esteemed as such that had been harvested and worked by the gentiles of that place and who are not obligated in the laws of the Seventh Year. This, therefore, made it permissible unto Jews to purchase from them such items.

These fruits are tithed as demai-produce in Caesarea: wheat and [if] bread stuffs the dough-portion is always removed, but as for wine and [olive] oil, dates, rice and cumin, lo! These are permitted during the Seventh Year in Caesarea, but on the remaining years of the seven-year cycle they are mended by separating [only] the demai tithe. Now there are some who prohibit [eating] white-petal grape hyacinths[138] that come from the King's Mountain.[139] Unto which place [is it considered] 'within the parameters' of Caesarea? Unto Ṣuwarnah and the Inn of Ṭabitha and [the Inn of] 'Amuda,[140] and Dor and Kefar Saba,[141] and if there is any place purchased by an Israelite,[142] our masters (i.e. the rabbis) are apprehensive concerning it [i.e. in what concerns the requirement to separate tithes]. Shalom.[44][143]

Addendum: Permitted towns in region of Sebaste

Between the country of Judea and the country of Galilee lies an intermediate stretch of land known as "the strip of the Samaritans."[144] Jews often passed through the region, while en route from Galilee to Jerusalem during the three annual pilgrimages, and again when returning home.

Although the region of Samaria was not seized at the very outset by those Jews returning from the Babylonian exile,[145] the priests of Aaron's descent were still permitted to pass through their country, without fear of contracting defilement in respect to the country of the gentiles. Nonetheless, with respect to fruits and vegetables had in Samaria, there were some places in Samaria that were exempt from tithes, as if they had been a foreign land.

The Jerusalem Talmud, when speaking about the impropriety of leaving the Land of Israel, describes the standard rule of practice of the time: "Said Rabbi Abbahu: 'There are hamlets belonging to the Samaritans wherein it has been customary to permit [a Jew's passage through them], since the days of Joshua, the son of Nun, and they are permitted' (i.e. released from the laws requiring tithing of produce)."[146] The reason for this exemption is explained by Talmudic exegete, Solomon Sirilio, as being that these villages in Samaria and their suburbs had the status of feudal or usufruct lands given by grant from the State to farm-laborers for a share of its increase, while the majority of increase accrued unto the State.[147] This was enough to exempt such produce from the requirement of tithing, since the kingdom (Ptolemaic or Roman, or otherwise) had not forfeited its hold over such lands, and since the Jewish regulations for tithing prescribe that produce or grain that is to be tithed must be the property of its tither, in accordance with Deuteronomy 14:22, "…you shall tithe all the produce of your seed" – meaning, your seed, but not the seed belonging to others.[148] The following list of towns concerns those hamlets held by the State (kingdom) in the region of Sebaste (the biblical city of Samaria) and which were, therefore, exempt from the laws of tithing.[149] The list is not known from any other source, and is only alluded to in the Jerusalem Talmud.[150]

The towns that are permitted[151] in the region of Sebaste [are as follows]: Iḳbin,[152] Kefar Kasdiya,[153] 'Ir (sic),[154] Azeilin, [155] Shafīrīn,[156] 'Ananin,[157] the Upper Bal'am,[158] Mazḥaru,[159] Dothan,[160] Kefar Maya,[161] Shilta,[162] Penṭāḳūmewatha, [163] Libiya, Fardeseliya,[164] Yaṣat,[165] Arbanūrin,[166] Kefar Yehūdit,[167] Mūnarit,[168] and half of Shelāf.[44][169]

By this it is implied that other towns and villages that were settled by the Samaritans, such as Gebaʻ[170] and Badan, fruits grown therein were still under the obligation to have all tithes separated therefrom before they could be eaten.[171]

| Original Hebrew-Aramaic transcript |

|---|

|

שלום הפירות הללו אסורין בבית שאן בשביעית ובשאר שבוע מתאסרין[172] דמי הקישואין והאבטיחין והממלפפונות והאסטפליני והמינתה הנאגרת בפני עצמה ופול המצרי הנאגד בשיפה והקפלוטות מן העצרת עד החנוכה והזירעונין והקצע והשמשמין והחרדל והאורז והכמן והתורמסין היבישין והאפונין הגמלונין הנימכרין במידה והשום ובצלין בני מדינה הנימכרין במידה והבולבסין והתמרין אפסיות והיין והשמן בשביעית שביעית שני שבוע דמי והפת חלה לעולם אילו המקומות המותרין סביבות בית שאן מן הדרום שהיא פילי דקמפון עד חקלה חיורתה מן המערב שהיא פילי דזיירה עד סוף הרצפה מן הצפון שהיא פילי דסכותה עד כפר קרנוס וכפר קרנוס כבית שאן ומן המיזרח שהיא פילי דזבלייה עד נפשה דפנוקטייה ופילי דכפר זמרין ופילי ראגמה[173] לפנים מן השער מותר ולחוץ אסור העיירות האסורות ביתחום סוסיתה עינוש ועינחרה ודמבר עיון ויערוט וכפר יחריב ונוב וחספייה וכפר צמח ורבי היתיר כפר צמח העיירות שהן ספיק בתחום נווה ציר וצייר וגשמיי וזיזון ורנב וחרבתה ואיגרי חוטם וכרכה דבר הרג העיירות אסורות בתחום צור שצת ובצת ופימצובה וחנותה עלייתה וחנותה ארעייתה וביברה וראש מייה ואמון ומזה היא קסטלה וכל מה שקנו ישראל נאסר תחומי ארץ ישראל מקום שה[חזיקו][174] עולי בבל פורשת אשקלון וחומת מיגדל שרושן דור וחומת עכו וראש מי גיאתו וגיאתו עצמה וכבר[תה וב]ית[174] זניתה וקסטרה רגלילה וקובעייה ראייתה וממצייה דירכתה ומלתה דכוריים וסחרתה דיתי[ר ונחל]ה[174] דבצאל ובית עיט וברשתה ואולי דבתה וניקבתה רעיון ומסב ספנחה וכרכה רב[ר ס]נגורה[175] ותרנגולה עלייה דקיסריון ובית סבל וקנת ורקם טרכון זימרה דמתחם לבוצרה ינקה זחשבון[176] ונחלח[177] דזרד איגר סהדותה נימרין ומלח רזיזה רקם דגיאה וגנייה דאשקלון ודרך הגדולה ההולכת למירבר[178] הפירות הללו אסורין בפנים[179] בשביעית ובישאר שני שבוע הן מתעסרין דמיי משלם האורז והאגוזין והשמשמין ופול המצרי יש אומרין אוף אחוניות הבכירות הדי[180] אלו בשביעית שביעית ובשאר שני שבוע הן מתעסרין וריי[181] ואפילו מן תרנוגלה עלייה ולחוצ הפירות הללו מתעסרין דמיי בקסרין החיטין והפת חלה לעולם והיין והשמן והתמרין והאורז והכמן הרי אלו מותרין בשביעית בקסרין ובישאר שני שבוע הן מתקנין דמיי ויש אוסרין בולבסין הלבנין הבאין מהר המלך ועד איכן סביב לקיסרין עד צוורנה ופנדקה דטביתה ועמודה ודור וכפר סבה ואם יש מקום שקנו אותו ישראל חוששין לו רבותינו שלום העיירות המו<ת>דות[182] בתחום סבסטי איקבין וכפר כסדיה ועיר[183] ואזילין ושפירין ועננין ובלעם עלייתה ומזחרו ודותן וכפר מייה ושילתה ופנטאקומוותה ולבייה ופרדיסלייה ויצת וארבנורין וכפר יהודית ומונרית ופלגה דשלאף |

See also

References

- Feliks, Yehuda (1986), pp. 454–455 (the actual time-frame of its making is disputed)

- Feliks, Yehuda (1986), pp. 454–455, who puts the Jerusalem Talmud's redaction no later than the end of the 3rd century CE, and the making of the mosaic immediately thereafter; Sussmann, Jacob (1975). Jewish legal inscription from a synagogue, p. 124. Israel Museum, Jerusalem. Retrieved on 2019-07-15 from https://www.imj.org.il/en/collections/395953.

- Vitto, Fanny (1975), p. 119

- The actual archaeological site was located ca. 800 metres (2,600 ft) northwest of Tel Rehov. See Vitto, Fanny (2015), p. 10, note 2.

- Sussmann, Jacob (1975), pp. 123, 124. Quote: [p. 123] "The inscription contains twenty-nine long lines, among which are 1807 letters! It is, by far, larger than all the inscriptions discovered until now among mosaic flooring, whether those belonging to ancient synagogues or those belonging to other structures. Thus, for example, it is more than three-times larger than the inscription found at Ein Gedi, which was discovered a few years ago, and which was, until now, the largest one discovered in the country." [...] [p. 124] "This is the first time that we have access to any Talmudic text inscribed close to the time of its inception and in close proximity to the centers of Talmudic formulation in the Land of Israel, a text that was inscribed, presumably, not too far after the redaction of the original Palestinian work, and in a place that is nigh the spiritual center of the Land of Israel during the Talmudic era: viz., Tiberias of the 5th-century (B)CE (sic). The text before us is not dependent upon the textual tradition of handwritten manuscripts, the pathway in which the Palestinian Talmudic literature has reached us; nor was it transferred unto us by way of reed pens (calamus) used by the scribes, copyists and proofreaders of various kinds, and for this reason it is invaluable for offering a critique on the Talmudic text. What is especially important is the clear Palestinian spelling of words, and their original versions of many geographical place-names, two areas that were rife with copyist-errors, and those made by proofreaders." END QUOTE

- Sussmann, Jacob (1975), p. 123

- Vitto, Fanny (2015), p. 7; Sussmann, Jacob (1975), p. 124; et al.

- Ben David, Chaim (2011), pp. 231-240

- Ben David, Chaim (2011), p. 238; Lieberman, S. (1976), p. 55; et al.

- The Baraitta of the borders of Eretz-Israel is, for all practical purposes, only a geographical reference to the old borders, as once settled, but not an ethnographic reference to the border for all time, since demographics change.

- Sussmann, Jacob (1975), p. 124; Feliks, Yehuda (1986), p. 454; Jewish legal inscription from a synagogue, Israel Museum, Jerusalem

- Mazar, A. (1999)

- Onomasticon (1971), "Roōb" (entry No. 766)

- Marcellius, R.P. Henricus (n.d.), p. 469 (s.v. Roob)

- Feliks, Yehuda (1986), pp. 454–455

- Alexandre, Yardenna (2017)

- Vitto, Fanny (1975), p. 119; Vitto, Fanny (2015), p. 3

- Archaeology Wing - Ward 6 (The Holy Land).

- Vitto, Fanny (1974), pp. 102–104

- Sussmann, Jacob (1975), p. 124

- Babylonian Talmud (Hullin 7a; Yebamot 16a); Maimonides (1974), vol. 4, Hil. Terumot 1:5–6

- As argued by Ishtori Haparchi (2007), pp. 40, 42. Although Rashi in BT Hullin 6b (s.v. את בית שאן כולה) says that Beit She'an was not part of the Land of Israel, Ishtori Haparchi argues that the sense here is to places not captured by the Returnees from Babylon, although they were conquered by Joshua, and which places have only the technical name of "outside the Land of Israel," just as we see with Akko in BT Gittin 76b. Likewise, Beit She'an was subdued by Israel during the time of Joshua, forcing its inhabitants to pay tribute unto Israel (BT Hullin 7a on Judges 1:27–28), but was not taken by the Returnees from Babylon.

- As explained by Menachem Meiri in his Beit HaBechirah (Hullin 6b, s.v. בית שאן), although Ishtori Haparchi (Kaftor Vaferach) disputes this, saying that the land was always consecrated, but that the laws regarding the land differed with Israel's return from the Babylonian exile.

- Safrai, Z. (1977), p. 17 (note 91). The term "demai" is a Halakhic term meaning "dubious," referring to agricultural produce, the owner of which was not trusted with regard to the correct separation of the tithes assigned to the Levites, although the terumah (the part designated unto priests) was believed to have been separated from such fruits. In such "dubious" cases, all that was necessary was to separate the one-tenth portion due to the priests from the First Tithe given to the Levites, being the 1/100th part of the whole. The Second Tithe is also removed (redeemed) from the fruit in such cases of doubt.

- Jerusalem Talmud, Demai 2:1 (Commentary of Solomon Sirilio); p. 16a in the Oz veHadar edition of the Jerusalem Talmud.

- Josephus mentions a population of above 13,000 Jews in Beit She'an at the outset of the war with Rome in the second half of the 1st century CE. See Josephus (1981), s.v. The Jewish War 2.18.3. (p. 493).

- Babylonian Talmud (Hullin 6b–7a); Jerusalem Talmud (Demai 2:1, s.v. ר' זעירא ר' חייא בשם ר' יוחנן רבי התיר בית שאן). According to the Talmud, Rabbi Judah HaNasi, taking as an exemplum an act that he heard performed by Rabbi Meir, released the entire region of Beit Shean from the obligations of tithing home-grown produce, and from observing the Seventh Year laws with respect to the same produce. He also did the same for the cities of Kefar Ṣemaḥ, Caesarea and Beit Gubrin. Rabbi Abraham ben David of Posquières holds that the enactment made by Rabbi Judah HaNasi applied only to vegetables, but not unto produce belonging to harvested grain (wheat, barley, spelt, etc.), the fruit of the vine (grapes, raisins, wine), or to produce derived from the olive tree (olives and olive oil), since the commandment to tithe these products is a biblical injunction.

- The Hebrew word used is הקישואין (ha-qishū'īn), a word that has since changed in meaning, but which had the original connotation of "cucumbers," as explained by Maimonides' commentary on Mishnah (Terumah 8:6), and just as it is found in the Aramaic Targums of Numbers 11:5 = בוציניא / קטייה, which words, in both cases, are explained by Smith, J. Payne (1903), pp. 39, 500, as meaning "cucumbers." Rabbi Saadia Gaon, in his Judeo-Arabic translation of the Pentateuch, uses the Arabic word אלקת'א (Ar. القثاء) for the same fruit, meaning "cucumbers," believed by scholars to have been the Armenian cucumber, or related varieties, such as Cucumis melo convar adzhur, and what is now known as al-fāḳḳūs in Arabic.

- The Hebrew word used here is a Greek loanword, המלפפונות (ha-melephephonot; sing. melephephon). The Jerusalem Talmud (Kilayim 1:2) relates an ancient belief that if one were to take a seed from a watermelon and a seed from an apple, and then place them together in an impression made in the earth, the two seeds would fuse together and become diverse kinds. "It is for this reason," says the narrator of the Talmud, "that they call it (i.e. the fruit) by its Greek name, melephephon. The old Greek word for "melon" was actually μήλο = mêlo(n) apple + πεπόν = pépōn melon, meaning literally "apple-shaped melon" (see: Random House Webster's College Dictionary, s.v. melon). This fruit, muskmelon (Cucumis melo), was thought to be a cross-breed between a watermelon and an apple. Maimonides, however, calls "melephephon" in Mishnah Kilayim 1:2 and Terumah 8:6 by the Arabic name, al-khiyyar, meaning "cucumbers" (Cucumis sativus) – far from being anything related to apples and watermelons. Talmudic exegete, Rabbi Solomon Sirilio (1485–1554), disputed Maimonides' view in his commentary on the Jerusalem Talmud (Kila'im 1:2, s.v. קישות), saying that Maimonides explained "melephephon" to mean in Spanish "pepinos" = cucumbers (Cucumis sativus), which, in the opinion of an early Mishnaic exegete, Rabbi Isaac of Siponto (c. 1090–1160), was really to be identified as “small, round melons” (Cucumis melo), since Rabbi Yehudah in our Mishnah holds that it is a diverse kind in relation to kishūt (a type of cucumber). Moreover, had the "melephephon" simply been a subspecies of kishūt, explained by Maimonides as having the meaning of al-fakous (Egyptian cucumber = Cucumis melo var. chate), in the Arabic language, they would not have been considered diverse kinds with respect to each other, similar to a black ox and a white ox that plough together are not considered diverse kinds. Nevertheless, today, in Modern Hebrew, the word melephephon is now used to denote "cucumbers," based on Maimonides' identification. Cf. Kapah, E. (2007), p. 74; Zohar Amar (2012), p. 79.

- The Hebrew word used here is האסטפליני (ha-esṭafulīnī), being a Greek loanword (σταφυλῖνος), meaning carrot (Daucus carota). Cf. Tosefta (Uktzin 1:1). Amar, Z. (2000), p. 270, cites physician and botanist Ibn al-Baitar (1197–1248), and his identification of flora described by Dioscorides, in Ibn al-Baitar's seminal work; see Ibn al-Baitar (1989), chapter 3, section 49, pp. 230– 231, and where he writes that this word can mean either the wild carrot, or cultivated carrot. The word was also used to describe the "white carrot," or what is now called in English parsnip (Pastinaca sativa). Ibn al-Baitar, who lived and worked in the Levant during the Ayyubid period, mentions "eṣṭafulīn" as being the carrot, so-called in the dialect spoken by the inhabitants of al-Shām (i.e. Greater Syria). The old Hebrew word for carrot is found in Tosefta Uktzin 1:1, but also in the Jerusalem Talmud (Maaserot, ch. 2; Hallah, 4 (end); Kila'im, ch. 1).

- The binding of the mint leaves (Menta) renders them liable to tithes and was a sign that they were not locally grown in Beit Shean. As for the mint grown in Beit Shean, it was customarily bound with other herbs and was exempt from tithing (Solomon Sirilio in Jerusalem Talmud, Demai 2:1).

- Called in Hebrew, פול המצרי (pōl ha-miṣrī), which is effectually translated as the "Egyptian fava bean," although not a real Fava bean, but as Rabbi Nissim has described it in his commentary known as Ketav ha-Mafteach, as being the bean which has the Arabic name of "lubiya" and which has "a dark eye in its center," meaning to say, our regular black-eyed pea, a sub-species of the cowpea (Vigna unguiculata).

- Meaning, freshly grown black-eyed peas with their bean pods. Those in the marketplace which were not bound by rush were locally grown produce, and exempt from tithing.

- The Hebrew word used here is הקפלוטות (ha-qaflūṭot), a word explained in the Jerusalem Talmud (Kilayim 2:1) as meaning "wild leeks," and by Nathan ben Abraham as "Syrian leeks" (Judeo-Arabic: אלכראת אלשאמי). This may refer to Allium ascalonicum, or to Allium ampeloprasum, but especially to Allium ampeloprasum var. kurrat. The latter herb is called in Arabic, in the dialect spoken in Palestine, karrāth berri (=wild leek).

- Explained by Rabbi Ze'ira in the Jerusalem Talmud (Demai 2:1) who said that wild leeks were prohibited in Beit Shean until tithed, because the majority of wild leeks brought into the Beit Shean marketplace during these months were those wild leeks grown in other places of the country which required tithing and the observance of Seventh Year restrictions (per after growths).

- The Hebrew word used here is הזירעונין, and refers principally to vegetable seeds, such as chickpeas (Cicer arietinum), or white peas (Lathyrus sativus), but not to cereal grains, as explained by Maimonides (1963), s.v. Kilayim 3:2, when describing the זרעונים of the previous Mishnah (ibid. 3:1) Cf. Maimonides (1967), s.v. Kelim 3:2.

- The Hebrew word used here is הקצע (ha-qeṣaʿ), more commonly spelled הקצח (ha-qeṣaḥ), since the Hebrew characters `ayin and ḥet were often interchanged in the Palestinian dialect. Cf. Pesikta de-Rav Kahana (1949), § 25, s.v. Shuvah, p. 162b, note 110.

- The Hebrew word used here is התורמסין (ha-tūrmosīn), a plant that is endemic to the hill-country of Judea. One of the more common species of lupine in the Land of Israel is Lupinus pilosus, and its large bean-like seed is ready for gathering in mid-summer. The seeds, though edible, require leaching several times in boiling water to cure them from their acidity and to render them soft. Once cured, they are served salted and peppered on a platter.

- Possibly, beans (Marcus Jastrow). The Hebrew words used here are האפונין הגמלונין (ha-afūnīn ha-ğimlōnīn), explained by Maimonides (1963), s.v. Kilayim 3:2, as meaning "large-sized peas." The Jerusalem Talmud (Demai 2:1), when speaking about the same peas, says that they were black in color (possibly, Vigna mungo). In any rate, these were to be distinguished from the ordinary pea (Pisum sativum). In Modern Hebrew, אפונים is understood as meaning garden pea (Pisum sativum). However, in old Hebrew, the word אפונים, as explained by Maimonides (1963), s.v. Peah 3:3 and Shabbat 21:3, meant garbanzo beans (Cicer arietinum), and where he uses the Judeo-Arabic word אלחמץ (garbanzo beans) for this plant. However, according to one of the oldest Mishnah commentaries now at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, in which it preserves the commentaries of Rabbi Nathan (President of the Academy in Eretz Israel during the 11th century), the word אפונים also had the equivalent meaning of the Arabic word الكشد, meaning stringed beans Vigna nilotica (see: Kapah, E. (2007), p. 25).

- The sense here is to spring onions.

- The Hebrew word used here is הבולבסין (ha-būlḇosīn), meaning the grape hyacinth (Muscari commutatum), endemic to Israel; a pleasant flowering plant with bulbous roots that are eaten fresh or pickled after boiling several times (see Method of Preparing). The plant was formerly cultivated in the hill country of Judea, and used also as an ornamental or for use in perfume. Other species of the grape hyacinth endemic to Israel are Muscari parviflorum and M. neglectum. The Hebrew word is a Greek loanword, derived from βολβός, an edible bulbous plant described in Theophrastus' Enquiry into Plants.

- The Hebrew words used here are התמרין אפסיות (ha-temarin afsiyot), which meaning is disputed by the commentators. Some say, by way of conjecture, that the adjective (Afsiyot) may probably be a denominative, meaning dates brought into Beit Shean from Ephes or Afsit. See Moses Margolies' Commentary P'nei Moshe in the Jerusalem Talmud; also Jastrow, M. (2006), s.v. אפסיות. Others (Löw, I. (1924–1934), vol. 2, p. 343) say that "it seems to be referring to late ripening dates." Elijah of Fulda says that the sense here is to "bitter dates." In contrast, Dr. Akiva London, an agronomist from the Department of Land of Israel Studies and Archaeology at Bar-Ilan University, has suggested that temarim afsiyot may have actually been a cultivar of date that grew either in Jericho (the Posittatium) and used primarily for matting, or else a cultivar that grew in Hippos near the Sea of Galilee, from whence it derived its name ipposiyot (rather than afsiyot), literally meaning "from Hippos." In any rate, this cultivar of date was brought into Beit Shean from other regions of the country and, therefore, was subject to tithes and to the laws regulating Seventh Year produce, but their locally grown dates were exempt from tithing.

- A rule that applies to places outside of the Land of Israel states that whenever one wishes to bake a quantity of bread, the Hallah, or dough portion taken from a quantity of kneaded flour, ca. 1.67 kilograms (3.7 lb), when the bread is baked, one small loaf is to be removed from the batch and designated as Hallah and burnt, while another small loaf from the same batch, being non-consecrated bread, is given to a small child of the priestly stock and eaten by him, so that the practice of giving the Hallah will not be forgotten amongst Israel. See: Ishtori Haparchi (2007), p. 32. (cf. Halakhot Gedolot, vol. 3 of the Makitzei Nirdamim edition, ed. Ezriel Hildesheimer, "Hilkot Ḥallah", Jerusalem 1987, p. 400).

- Vitto, Fanny (1974)

- That is to say, the country settled by Israelites upon their return from the Babylonian captivity.

- Sussmann, J. (1975), p. 126

- Formerly, dates (Phoenix dactylifera) grown in the Land of Israel were renowned for their high-quality, both, in sweetness and in moisture content. A nearly 2,000 year-old date pit retrieved from Masada was recently germinated in Israel, and DNA studies revealed that the cultivar, although not the same, was very similar to the Egyptian Hayani (Hayany) cultivar, a date that is dark-red to nearly black in color, and soft. (See: Miriam Kresh (2012-03-25). "2000-Year-Old Date Pit Sprouts in Israel". Green Prophet Weekly Newsletter. Retrieved 2012-05-13.).

- That is to say, when he released Israel from observing the restrictions associated with that year (such as the rabbinic prohibition of eating "aftergrowths," or the requirement to discard from one's home any Seventh Year fruit once the growing season for such fruit had ended and the like of such fruit could no longer be found in the fields (see: Ishtori Haparchi (2004), p. 62; Obadiah of Bertinoro). However, Ishtori Haparchi (2004), p. 68, has explained that Rabbi Judah HaNasi would still require the tithing of any of the five cereal grains, grapes, and olives in Beit She'an, since their ordinance is a rabbinic ordinance that is still applicable and has not been cancelled.

- Jerusalem Talmud (Shevi'it 6:4); p. 51a in the Oz veHadar edition, or 18a in most other editions.

- Meaning, those places which have the same status as Beit She'an owing to their proximity to Beit She'an, and if local Jewish husbandmen or gardeners should happen to grow their own produce, or if buyers should happen to buy locally grown produce from others, such fruits and vegetables are permitted to be eaten by them and others without tithing them, and without the strictures normally associated with Seventh Year produce.

- Text: פילי דקמפון (pillei dekumpon); the Aramaic word used for gate פילי is actually a Greek loanword, πύλη (pillei = gate) + ד (de = the genitive case of) + קמפון (ḳumpon = ḳumpon). The word, ḳumpon, is a Greek loanword, derived from κάμπον (campus), and used in Mishnah Kelim 23:2, s.v. קומפון. Rabbi Hai Gaon explains its import as meaning: "a [level] field where kings entertain themselves" (i.e. in the presence of their soldiers), hence: "Gate of the open field." Maimonides, writing similarly, says that it has the connotation of a "stadium, where the king's soldiers would show-off their valor and good horsemanship by riding their horses while standing upon the stirrups" (cf. Marcus Jastrow, Dictionary of the Targumim, s.v. קומפון). Rabbi Hillel ben Eliakim of Salonika (12th century CE) explained the word קומפון in the Sifrei of Deuteronomy as meaning, "hippodrome in the Greek language in which all the people enter." See Weiss, Zeev (2001), p. 40.

- The name of this place is written in Aramaic, חקלה = field + חיורתה = white (White Field).

- Text: כפר קרנוס (=The Village of Ḳarnos). In Pesikta de-Rav Kahana (1949), p. 66a, is mentioned a town by the name of כפר קריינוס (= Kefar Ḳarianos), perhaps being the same village named here.

- Meaning, the butts and bounds of Beit She'an and its special laws of release from tithing of produce, &c. apply to the village of Kefar Ḳarnos as well, making its inhabitants as the citizens of Beit She'an in this regard.

- The name of this place is written in Aramaic, פילי = gate + ד = the genitive case of + זבלייה = the dung spreaders. This last word, "dung spreaders," is the same word used in Midrash Rabba (Canticles Rabba 1:9): "Said Rabbi Elʻazar: In all my days, no man has ever gone into the House of Study before me. Neither have I ever left a man sitting there by himself while I departed. Once, I rose up [from my sleep] and I found those that spread manure (Aramaic: זבלייה) [in their fields] and those that mowed hay [who had already risen up before me to do their work], etc."

- The sense here is to a burial monument, just as the word נפש is explained by Rabbi Hai Gaon, in his commentary on the Mishnah (Seder Ṭaharot, Ohelot 7:1).

- Fanny Vitto understood the graphemes of the text to read: ופילי ראגמה = the Gate of Ragama, but since the Hebrew character resh (ר) is often confounded with daleth (ד), Sussmann, Jacob (1975), p. 125, has corrected the text to read: ופילי דאגמה = the Gate of the marshland.

- Meaning, the release from tithes applies to them as well only where produce is grown within the village walls.

- Meaning, the town that once stood 3 km. east of the lower eastern shore of the Sea of Galilee, also known as Qalʻat el-Ḥuṣn. The novelty of this teaching is that, although this part of the country was partly settled by Israel during their return from Babylonia, by the late 1st century CE, it was mostly populated by a non-Jewish majority, as evidenced by Josephus (The Jewish War ii.xviii.§5), who relates how the Syrians of that place persecuted the Jews during the First Jewish–Roman War. Elsewhere, Josephus (Antiquities xvii.xi.iv) writes that in the days of Herod Archelaus (died c. 18 CE), Hippos was already a Grecian city. According to Ishtori Haparchi (2004), p. 69, a discrepancy is found in the Tosefta. In one place (Ohelot 18:4) it says: "Towns that are swallowed-up in the Land of Israel, such as Sussitha and her neighboring towns, [or] Ashqelon and her neighboring towns, even though they are exempt from tithing and from the law of Seventh Year produce, they do not fall under the category of [defilement by] the land of the gentiles," but in another place (Tosefta, Shevi'it 4:10) it says: "The towns that are obligated in what concerns tithes in the region of Sussitha, etc." In one place it says they are exempt, but in another place it says they are obligated. Ishtori Haparchi (ibid.) attempts to rectify the discrepancy by saying that "region" (in Shevi'it) and the "neighboring towns" (in Ohelot) have two distinct halakhic implications. The "neighboring towns" (in Ohelot) refer to non-Jewish towns (such as Sussitha) stretching along the periphery of Israel's borders; the word "region" (in Shevi'it) refers to Jewish towns in the region of Sussitha. In any rate, by saying "towns that are prohibited," the Rehob inscription requires tithing in such places.

- Text: עינוש, a place identified by Avi-Yonah, M. (1979), p. 170, as being what is now called `Awânish.

- A destroyed village in the upper Golan Heights, ca. 16 kilometers (9.9 mi) east of where the Hasbani River, and the Dan and Banias tributaries converge to form the Jordan River. In the Rehob mosaic, the name is written as one word, עינחרה.

- Possibly referring to a destroyed village by that name and which formerly stood 2 kilometers (1.2 mi) from 'Ain-Ḥura in the upper Golan Heights, some 14 kilometers (8.7 mi) east of the confluence of the Banias, Dan and Hasbani Rivers, which form the upper Jordan River. The town was known by its Arab inhabitants as 'Ayūn al-Ḥajal (ca. 3 kilometers (1.9 mi) south of Buq'ata). There was also a farm by the same name, Al 'Ayūn (Al 'Uyūn) in the southernmost end of the Golan Heights, situated ca. 4.8 kilometers (3.0 mi) east of the Sea of Galilee at its southern end, and ca. 1.2 kilometers (0.75 mi) north of the Yarmuk River.

- Avi-Yonah, M. (1979), p. 170, identified this place with a ruin, now known as Khurbet el 'Arayis, to the east of Kefar Haruv, on the north bank of the Yarmuk River.

- Now a destroyed village in the southern Golan Heights, 2 kilometers (1.2 mi) east of the Sea of Galilee, formerly called "Kafr Ḥarib" by its Arab inhabitants, being but a corruption of the older name "Kefar Yaḥrib." Adjoining thereto on a precipice north of the old village ruins was built the newer Israeli settlement of Kefar Haruv in 1973, a little southeast of Kibbutz Ein Gev.

- A town situated ca. 12.5 kilometers (7.8 mi) east of the Sea of Galilee, formerly called by its Arab inhabitants "Nab," but resettled by Jews in 1974 and now called Nov. (This place is not to be confused with "Nob" the city of priests, near Jerusalem, during the period of King Saul and David) See: Dan Urman and Paul V.M. Flesher (1998), p. 565.

- HaReuveni, I. (1999), pp. 662–663

- Text: חספייה (Ḥisfiyyah), a town called Khisfīn by its Arab inhabitants, but since 1978 resettled by Israel and given the name Haspin, located ca. 14.2 kilometers (8.8 mi) east of the Sea of Galilee. According to archaeologist, Avi-Yonah, M. (1979), p. 170, this is the town that is called Caspien or Chasphon in the Book of Maccabees (1 Macc. 5:26; 2 Macc. 12:13).

- In Gleichen, Edward, ed. (1925). First List of Names in Palestine - Published for the Permanent Committee on Geographical Names by the Royal Geographical Society. London: Royal Geographical Society. p. 10. OCLC 69392644., this site is identified with Samakh, Tiberias. Meaning, Kefar Ṣemaḥ was not considered a place settled by the people who returned from Babylon, and therefore its fruits and vegetables did not require tithing. Nor did the Seventh Year laws apply to produce.

- A town, now called Nawā, situated further northeast from Sussitha, formerly one of the principal towns in the territory of Hauran, and which is now a part of Syria. Eusebius calls it a Jewish town (Onomasticon 136:3). Naveh and the neighboring gentile city of Ḥalamish were often at odds (Lamentations Rabba 1:60).

- Text: ציר, a town written in plene scriptum; perhaps the same town mentioned in Joshua 19:35, צֵר, although there written in defective scriptum. The town was one of many settled by the tribe of Naphtali during the time of Joshua. Samuel Klein, whose textual variant reads צור (Ṣūr), thought this place to be Ṣureya (Sreya), a place northeast of Naveh, in Syria. See Klein, S. (1925), p. 42.

- Text: צייר. Avi-Yonah, M. (1979), pp. 168–169, identified this place with the small village in Syria east of the Golan Heights, near the Israeli border, and now called Sreya. The place can be seen on the Library of Congress map of the Golan Heights and vicinity, October 1994, a little to the southeast of Qāsim.

- Text: גשמיי. Avi-Yonah, M. (1979), pp. 168–169, identified this place with Jāsim (also spelt Qāsim), a Syrian village east of the Golan Heights and north of Naveh, near the Israeli border. The same identification is given by Klein, S. (1925), p. 42. The village (Qāsim) can be seen marked in orange on the Library of Congress map of the Golan Heights and vicinity, October 1994.

- This place is still an inhabited village today, located southwest of Naveh (Nawa, Syria), and lying on the Syrian side of the Syrian-Jordanian border. It can be seen in the Library of Congress map of the Golan Heights and vicinity, October 1994, with village marked in orange color. Zayzun of the Rehob Mosaic is not to be confused with Zayzun in the far north of Syria, near the Turkish-Syrian border.

- The Rehob inscription reads: רנב וחרבתה, which can effectually be translated as "Renab and its ruin," or "Renab and Ḥorḇatah" (meaning, a place name). Samuel Klein cited a variant text which exchanged the resh in "Renab" for a daleth, giving the reading "Denab," which he thought to be al-Deneiba, east of Naveh in Syria. See: Klein, S. (1925), p. 42

- A place formerly so-called, having the meaning of "Nose-like Heaps [of stone]," איגרי = heaps + חוטם = nose / nostril; now unidentified. The variant reading in the Tosefta 4:8 records יגרי (heaps of stone) instead of איגרי, but by the inscription's use of the same word and spelling further along in the construct state, איגר סהדותה, a sentence derived from Genesis 31:47 (Stone Heap of Witness), it is evident that the sense here is to "heaps of stone." Samuel Klein thinks this place to be what is, today, known as 'Ataman, in Syria, east of Zayzun. See: Klein, S. (1925), p. 42.

- The Aramaic is represented by the words: כרכה דבר הרג; meaning, כרכה = the walled city + דבר = of the son of + הרג = Harag. The place has yet to be identified.

- On the far western coastline, the precise place marking the extent of the boundary of Eretz Israel in the vicinity of Chezib was understood to be the River below Chezib (i.e. Nahr Mefshukh, or what is now called Naḥal Ga'athon), in accordance with a teaching in Tosefta (Shevi'it 4:6): "Which is the Land of Israel? From the river south of Achzib, etc." Some have erroneously identified this river as the Kasmieh River (also called Litani River) in southern Lebanon. The river (Nahr Mefshukh) is shown in the Palestine Exploration Fund map produced in 1878. As one moved further east of this place, the border extended northward.

- A view largely held by many, including by Ishtori Haparchi (2004), p. 69 (note 120). Although the butts and bounds of Akko were mentioned to imply that bills of divorce written there must be done in the presence of competent witnesses, see the Babylonian Talmud (Gittin 76b), where it states that whenever the Rabbis would escort their companions northbound, they would only go with them as far as Akko, so as not to leave the border of the country taken by the Returnees from Babylonia. Nevertheless, part of the country taken by the Returnees from Babylon also bypassed Akko to the right-hand side, and extended as far as Achziv (Chezib) to the north, just as it is explained in the Tosefta (Ohelot 18:14): "He that walks [northbound] from Akko to Chezib, from his right-side towards the east the route is pure in terms of [defilement from] land of the gentiles, and he is obligated in what concerns the tithe and Seventh Year produce, until it becomes known [to him once again] that it is exempt; but from his left-side towards the west the route is defiled in terms of land of the gentiles, and [such produce] is exempt from tithes and from the laws governing the Seventh Year, until it becomes known [to him once more] that it is obligated, until he reaches Chezib." The same Baraitta is quoted in the Jerusalem Talmud, (Shevi'it 16a). On the Palestine Exploration Fund Map of 1878, the coastal city of Achziv is written there by its Arabic name, ez-Zīb.

- The Mishnah (ed. Herbert Danby), Oxford University Press: Oxford 1933, s.v. Tractate Demai 1:3

- Based on Tosefta Demai 1:10 (end), which states: " [Produce purchased from] a caravan which goes down to Kheziv is liable [to be tithed] since it is presumed to have come from Galilee."

- As evidenced by Rabbi Ami in the Jerusalem Talmud (Rome MS.) on Demai 2:1, when referencing these same cities between Akko and Tyre.

- Frankel, Rafael; et al. (2001), p. 153 (Appendix III)

- A Phœnician border-town, identified as el-Baṣṣeh (Arabic: البصة), a village situated 19 kilometers (12 mi) north of Acre and 4 kilometers (2.5 mi) southeast of Ras an-Naqura, abandoned in 1948 by its Arab citizens and subsequently resettled by Israel in 1951. See: Avi-Yonah, M. (1976), p. 42; Marcus Jastrow, Dictionary of the Targumim, s.v. בצת, citing Neubauer's Geography of the Talmud, p. 22. The site is shown in the Palestine Exploration Fund Map made by Lieut C. R. Conder & HH Kitchener in May of 1878.

- Until 1940, this place had long been uninhabited and called by its Arabic corruption, Khurbet Maṣ'ub (Arabic: مصعُب), "the Ruin of Maṣ'ub," but a collective community based on agriculture has since been built near the old-site and renamed Matzuva. The site is shown a few hundred metres to the east of el-Basseh in the Palestine Exploration Fund Map made by Lieut C. R. Conder & HH Kitchener in May of 1878. Marcus Jastrow, citing Neubauer, A. (1868), p. 22, also identifies this proper noun with the ruin known as Maasûb. See also: Haltrecht, E. (1948), p. 43.

- The text of the Rehob inscription reads: חנותה עלייתה (Ḥanūtha 'aliyatha), meaning literally, "the upper shop." In the 19th century, the site was a ruin called Khurbet Hanuta, located a little northeast of el-Baṣṣeh, and shown in the Palestine Exploration Fund Map made by Lieut C. R. Conder & HH Kitchener in May of 1878, and described in SWP:Memoirs. In 1938, a Kibbutz was built on the ancient site, now called Hanita, along the Israeli-Lebanese border in northern Israel.

- The text of the Rehob inscription reads: חנותה ארעייתה (Ḥanūtha 'aliyatha), meaning literally, "the nether shop" (Ḥanūtha ara'itha). See previous note for its location.

- The word, as spelt in the original mosaic, reads as ביברה, which Raphael Frankel suggests is the town formerly known as Bibra [sic], but which is now a ruin, known as Khurbet Bobriyeh, and which lies ca. 5.5 kilometers (3.4 mi) east of Naḥal Keziv, what was formerly called Wady el Kurn (see: Raphael Frankel - 1979). The ancient mound is shown on the Survey of Western Palestine map produced by CR. Conder and H.H. Kitchener (sheet # 3). See Safrai, Z. (1977), p. 17, who suggested that the word Bebarah (or Bebadah, as he understood its graphemes) is actually a contraction of two words: Be (בי), meaning "House" + Bada (בדה), meaning the shortened form of ʿAbdah, being the ancient city of ʿAbdon, a city called in late antiquity by the name ʿAbdah and where is now built the Israeli settlement Avdon.

- Hebrew: ראש מייה; Samuel Klein suggests its identification with Ras al-Ain (Lit. Fountain-head), just as its name implies in Hebrew, a place located 6 km. south of Tyre, in the municipality of Batouliyat in south Lebanon, in the District of Tyre (Sour), which, to this very day, is the main source of water for the people of Tyre since Phoenician days. Its artesian wells gush up into stone reservoirs that have been maintained through the ages. One of the reservoirs fed the arched aqueducts of the Roman period that once stretched as far as Tyre. Remains of these aqueducts can be seen along the Roman road running under the monumental arch on the necropolis. Klein's identification of this place is supported by Ze'ev Safrai (1977, p. 17). A. Neubauer (1868), citing Robinson, also identifies it with Ras el-Ain of southern Lebanon.

- Archaeologist, J. Braslawski, conjectured by giving plausible arguments that it is the place now called Khurbet Umm el Amud, ca. 2 km. north of Kh. Mazi, and what is shown in the Palestine Exploration Fund Map made by Lieut C. R. Conder & HH Kitchener in May of 1878. It is said to be the Ḥammon of Joshua 19:28. See also Braslawski, J. (1942), pp. 26–27.

- Text: מזה היא קסטלה. The word "castella" is a Latin loanword, from castellum, a word which, in Latin, has the connotation of either: castle, village, stronghold, citadel, or reservoir (water tower). The identification of this place is now a ruin, called by the name Khurbet Mazi, to the immediate south-side and adjoining to the present town of en-Nakurah in southern Lebanon. The site is shown in the Palestine Exploration Fund Map made by Lieut C. R. Conder & HH Kitchener in May of 1878. Archaeologist, J. Braslawski, holds this to be the ancient site mentioned in late 2nd-century Jewish sources. See: Braslawski, J. (1942), pp. 26–27.

- According to a Tosefta (Ma'aser Rishon 3:8), a rabbinic ordinance prohibited taking out untithed fruits and vegetables from the Land of Israel, and any of such fruits and vegetables that are taken outside of the country for selling to gentiles are presumed to be untithed.

- Frankel & Finkelstein (1983), pp. 39–46.

- This word was damaged in the mosaic floor, but has been reconstructed by Jacob Sussmann (1975).

- The words inscribed in the Rehob mosaic are פורשת אשקלון, meaning, the Crossing of Ashkelon, or the Passage of Ashkelon. The same description of the boundaries of the Land is brought down also in Sifre on Deuteronomy 11:24 and in Tosefta (Shevi'it 4:11).

- The Rehob mosaic has inscribed חומת מיגדל שרושן (wall of Sharoshan Tower), without the words "of Caesarea." The completion of this text is based on a conflation of the Rehob mosaic with its parallel text found in the Tosefta (Shevi'it 4:11), which latter places the Sharoshan Tower in Caesarea (חומת מגדל שרשן דקיסרי). Some suggest that this Sharoshan Tower may have actually been the old Hebrew appellation given for the city of Caesarea, or what Josephus calls "Straton's Tower" (Στράτωνος Πυργὸς). See Josephus (1981), s.v. Antiquities 15.9.6. (p. 331). The copyist of the Leiden MS. of the Jerusalem Talmud (from which text all modern copies of the Jerusalem Talmud were printed), while copying his own manuscript from an older version had at his disposal, seemed to have been unsure about the proper rendering of the word Sharoshan, or else made use of a corrupt text, and wrote in reference to the same place: חומת מגדל שיד ושינה, dividing the word Sharoshan into two words, viz. "the wall of the Tower of Sīd and Shinah."

- The coastal city of Dora, ca. 8 kilometers north of Caesarea Maritima.

- This place has been identified by archaeologists, Raphael Frankel and Israel Finkelstein (1983), p. 43, and where they describe it as "natural springs issuing from the fountain-head of the riverine-brook called Gaʻaton, being two springs: ʻain a-tinah and ʻain al-ʻanqalit." The aforenamed place is situated inland between Achziv and Akko. Today, the mound is located to the northwest of the modern-day kibbutz, Ga'aton. See: Frankel & Finkelstein (1983), pp. 39–46.

- Text: וגיאתו עצמה. Described by archaeologists, Raphael Frankel and Israel Finkelstein, as the ruin, Khurbet Ǧa'thūn (Ja'thun), situated ca. 3 miles east of el-Kabireh, now near the present-day site of kibbutz Ga'aton.

- The last letters of this word were broken in the Rehob mosaic, but reconstructed by using the parallel text in Sifrei (on Deuteronomy 11:24). Place identified by archaeologists, Raphael Frankel and Israel Finkelstein (1983), as the village site of Al-Kabri which, in turn was built to the east of the old ruin Tell Kabri. Today, a kibbutz by the name of Kabri is built on the site Al-Kabri. The place, under its variant spelling, el-Kabry, can be seen in the Palestine Exploration Fund Map of 1878. Samuel Klein (1928), citing G. Dalman (Palästina Jahrbuch, pp. 18–19) had formerly identified this place with Kh. Kabarsa, directly north of Akko where Nahariya is now built, but with the discovery of the Rehob mosaic its place has been readjusted (Raphael Frankel and Israel Finkelstein, 1983).

- Part of the writing of this toponym was defected in the Rehob mosaic. However, its reconstruction by Jacob Sussmann (1975) is based after its parallel text in Sifrei (on Deuteronomy 11:24). Archaeologist, Raphael Frankel, identified the town as being what is now a ruin, Kh. Zuweinita, about 5 km. (3.1 miles) northeast of Kabri and shown in the Palestine Exploration Fund Map of 1878. See: Frankel, Raphael (1979), pp. 194-196.

- Text: קסטרה רגלילה (sic), but corrected to read קסטרה דגלילה. Identified by archaeologists, Raphael Frankel and Israel Finkelstein (1983), as Khurbet Jalil (Kh. Jelil). Kh. Jelil is shown on the Palestine Exploration Fund Map of 1878, north of Wady el Kûrn. Kh. Jelil would have been the first station one encounters as he proceeds northbound across Wady el Kûrn. Today, the ruins are in the vicinity of the new settlements of Eilon and Goren.

- The original text reads: קובעייה ראייתה, the genitive case “of” (ד) being mistaken for the letter resh (ר) by its copyist, but corrected by Jacob Sussmann (1975) to read קובעייה דאייתה. The Aramaic word קובעייה (Syriac ܩܘܒܥܝܐ) has the connotation of “hats; habits; hoods; caps” (Payne Smith, Thesaurus Syriacus), which words when joined together mean “The Hats of Ayta.” Abel, F.M. (1933), p. 309, translates the same name as "Teats of ʻAïtha," and which he said should be identified with the Lebanese village of ʻAīṭā eš-Šaʻb. Likewise, the place has been identified by archaeologists, Raphael Frankel and Israel Finkelstein (1983), as being Ayta ash Shab (sic) in south Lebanon, ca. 1.5 km. from the Israeli border, and about 14 kilometers (8.7 mi) northeast of Qal'at al-Qurain. Neubauer thought this place may have been el-Koubéa (now Qabba'a), north of Safed, as did Joseph Schwarz. See: Neubauer, A. (1868), p. 15) and Schwarz, Joseph (1969), p. 35.

- Neubauer, A. (1868), p. 16, wrote: "[It] is perhaps Memçi, a village at the foot of Mount Hermon (djebel Esh-sheikh). The Tosefta reads here ממציא דגתא. It would then be Memçi from the province of Ghouta (a province where Mount Hermon is located)." Today, in the Quneitra Governorate, there is a depopulated village called Mumsiyah.

- Text: מלתה דכוריים. Believed by Raphael Frankel and Israel Finkelstein (1983) to be the ruin known as Khurbet Kuriyyah, a place situated to the north of Kafr 'Ain Abil in south Lebanon.

- Text: ...סחרתה דיתי. The last letter of this proper noun was defected in the Rehob mosaic, but its reconstruction was made by comparing it with parallel texts in Sifrei on Deuteronomy 11:24, and Tosefta (Shevi'it 4:11). The Aramaic word סחרתה (or what is in Syriac ܣܚܪܬܐ), according to Smith, J. Payne (1903), p. 372 (online), has the meaning of "a walled enclosure; a palace." Together, the sense would be: the Walled enclosure of Yatīr. Jastrow, M. (2006), s.v. סחרתא (p. 972), believes it has the connotation of "neighborhood," being a derivative of the word סחר = "enclosure." Accordingly, the meaning would be "environs" – viz. the environs of Yatir (cf. Ezek. 32:22). In any case, the place has been identified by archaeologists, Raphael Frankel and Israel Finkelstein (1983), as being the village Ya'ṭer in Jabal Amel, in south Lebanon.

- This part of the Rehob mosaic was partly defective, but its reconstruction by Jacob Sussmann (1975), based on a comparison with its parallel text in Sifrei on Deuteronomy 11:24, reads: נחלה דבצאל. Baṣāl itself has been identified by archaeologists, Frankel & Finkelstein (1983), p. 44, as the riverine brook (Heb. נחל) that is located near a former Lebanese town by the name of Baṣāl. Today, a mountain in southern Lebanon bears the name, Jabal Bâssîl, believed to be a corruption of the former name. The variant forms of spelling for Jabal Bâssîl are: Jebel Bassîl, Jabal Bāşīl, Jabal Bâssîl, Jabal Basil, Jabal Bassil, Jabal Bâssîl, Jabal Bāşīl, Jebel Bassil, Jebel Bassîl. On an 1858 map of southern Lebanon compiled by C.W.M. van de Velde, to the west of Aitha esh-Shab, there is a mountain called el-Bassal Ajleileh, directly adjacent to and south of Rameh (Ramah) and east of Terbikhah (see Section 3 in Map). The riverine brook (naḥal) runs from it in a south-easterly direction to the sea.

- Frankel & Finkelstein (1983), p. 44, have identified this place with Aita az Zutt (also known as Aita al Jebal) in south Lebanon.

- Text: ברשתה, a place identified by archaeologists, Frankel & Finkelstein (1983), p. 44, as the Lebanese village Baraachit in Jabal Amel of South Lebanon; Abel, F.M. (1933), p. 309, s.v. Meraḥseth.

- There is often confusion between the Hebrew letters daleth (ד) and resh (ר) in the Rehob mosaic. Archaeologist, Fanny Vitto, understood the graphemes of the text here to read with the genitive case "of" = אולי דבתה, as in: Awali of Battah, or Awali Debattah), although Frankel and Finkelstein saw the same word as carrying the Hebrew character resh (ר) and wrote in their essay, אולי רבתה (the Great Awali).

- Text: ניקבתה רעיון, the text corrected to read: ניקבתה דעיון, a place identified by archaeologists, Raphael Frankel and Israel Finkelstein (ibid., p. 44), as Marjayoun (Merj 'Ayun). The word ניקבתה, according to the said archaeologists, means "cleft; mountain pass." Cf. Jastrow, M. (2006), s.v. נקיפתא = Hollow of Iyyon; in Conder & Kitchener (1881), p. 96, they interpret its meaning as the Gorge of 'Iyyon. Iyyon (Ijon) itself was once a village, but is now a ruin called Tell Dibbin in the plain called Merj 'Ayyun, between the Upper Jordan and the Leontes River, first mentioned in II Kings 15:29 (See Muḳaddasi (1886), p. 95 note 5).

- Klein, S. (1928), p. 203, who wrote: "Sefanta (sic) can only be the es-Sefine located between Hasbaya and Rashaya." Klein, citing Hildesheimer, adds: "That it is 'too far up north' may surprise us, but does not speak in the least against the correctness of the equation."

- Text here defected in Rehob mosaic, but its reconstruction by Jacob Sussmann (1975) was based on parallel texts in Sifrei on Deuteronomy 11:24 and Tosefta (Shevi'it 4:11). Cf. Jastrow, M. (2006), s.v. בר סניגורא (p. 1007), where the words "Bar-Sannigora" can effectually be translated as 'The son of Sannigora," a border town between Syria and Palestine. Palmer, E.H. (1881), p. 28, identified the place with Khŭrbet Shâghûry (on Sheet ii of the SWP map) - "the ruins of Shâghûry (Shâgûr for Shanghûr, the Senigora סניגורא of the Talmud)." Abel, F.M. (1933), p. 309, citing Hirsch Hildesheimer, thought it to be Qalaʻat eṣ-Ṣubeibé (the Castle of Nimrod). The name "Bar-Sannigora" is also mentioned in the description of the northeastern border of the land of Canaan in the Targum Yerushlami (Targum Pseudo-Jonathan), on Numbers 34:8, as corresponding with the biblical Zedad: "...the outer reaches of the boundary thereof will be from the two sides reaching as far as to the walled cities of Bar-Za'amah, thought by Klein, S. (1939), p. 161, to mean "the son of Soëmos," a former governor of a tetrarchy about Libanus) and to the walled cities of Bar-Sannigora, and from the shape of the Rooster (Turnegol) as far as Caesarion (Baniyas), etc."

- Text: תרנגולה עלייה דקיסריון; = turnegolah 'aliyah de-qesariyon, a proper noun indicating that anything lying below this place is within the boundary of Israel, but anything lying above it is not. According to Wilson, John F. (2004), p. 76, the place has yet to be identified, but, using his own words, "it is reasonable that the term refers to the hill just behind and east of Banias where the ruins of the medieval castle of Subaybah now stand." The Castle of Subaybah is also known as Nimrod Fortress. Abel, F.M. (1933), p. 309, citing Hirsch Hildesheimer, disputes this view, saying that the walled city of Bar-Sannigora should be identified with Qalaʻat eṣ-Ṣubeibé (the Castle of Subaybah), but the place known as the "Upper Rooster" should be identified with Saḥītha, a town located between Baniyas and Beit Ǧenn in Hermon. A description of these places is had in the Targum Yerushlami (Targum Pseudo-Jonathan), on Numbers 34:8, as corresponding with the biblical Zedad: "...the outer reaches of the boundary thereof will be from the two sides reaching as far as to the walled cities of Bar-Za'amah and to the walled cities of Bar-Sannigora, and from the shape of the Rooster (Turnegol) as far as Caesarion (Baniyas), etc." According to Tosefta Shevi'it 4:11, the Upper Rooster was above Cesarea-Philippi.

- The Mosaic text clearly writes "Sabal" with the Hebrew letter "bet," and which the copyist of the Aramaic Targum Jonathan ben Uzziel on Numbers 34:9–10, when describing this region of the country, writes "Beit Sakal," the Hebrew "bet" being interchanged with "kaf." According to the Aramaic Targum, this place is associated with the biblical Ḥazar ʿEnan, translated in Aramaic as ṭirath ʿenawatha ("walled suburb of the springs"), a place in Israel's far northeast as one goes in the direction of Damascus. It was located between the "walled suburb of the springs" (Ḥazar ʿEnan) and Damascus.

- Text: קנת, a place mentioned in Numbers 32:42 and which Ishtori Haparchi (2007), p. 88, identifies with אל-קונייא (el-Quniyye), possibly Ein Qiniyye, ca. 3.5 kilometers (2.2 mi) southeast of Banias. According to Hildesheimer, Hirsch (1886), p. 50, there was also another place by the name Ḳanat (=Kanata or Kanatha), located in the middle of Batanea, at the point of today's ruins known as Kerak, in Syria's Daraa Governorate, meaning "fortress," 4 hours east of Edre'at in Wadi Talit. Avi-Yonah, M. (1949), p. 42, held the view that the reference here is to Canatha (Qanawat), in Syria, as did Freimark, P. (1969), p. 9.

- According to Jacob Sussmann, this was a place in the region of Trachonitis and is not to be confused with the other Rekem, now known as Petra in Arabia. See: Sussmann, Jacob (1976), p. 239.

- Text: טרכון, the usual designation for a wide area east of the Golan Heights (Gaulonitis).

- Klein, S. (1928), p. 206, following Sifrei on Deut. 11:24 and a manuscript of the Yalkut, corrects this to read: "Trachonitis of Zimra which is in the region of Buṣrah" (טרכונא דזימרא דבתחום בוצרא). He suggests that the name "Zimra" refers to a Babylonian Jew who was so-called and who, with his family and group of followers, had moved to that region of the country and settled there under the directives of Herod the Great, and were made exempt from paying taxes. Although they initially settled in the toparchy called Batanea which country is bounded with Trachonitis, they held sway over Trachonitis and protected Herod's subjects there from the brigandage of robbers. Based on this eponym, perhaps due to the benevolent acts of Zimra and his kin who built the country and protected its citizens, the pioneering founder's name was applied to the toparchy of Trachonitis. See Josephus (1981), s.v. Antiquities 17.2.1–3 (pp. 357–358).

- Buṣrah is now called Busra al-Harir, a town in southern Syria.

- Today, the site is a ruin bearing its old namesake, Tell Ḥesbān, located ca. 9 kilometers (5.6 miles) north of Madaba, in the plains east of the Dead Sea.

- A place mentioned also in the Hebrew Bible (Deuteronomy 2:13; Numbers 21:12, etc.) and being identified with Wadi el-Hesa (Arabic:وادي الحسا), a riverine gulch that stretches for ca. 35 miles in Jordan and empties into the Dead Sea. The first to identify this place as such was Edward Robinson, a view nearly unanimously accepted by scholarship today. Even so, there is still with respect to this place a conflict of opinions, with some holding "the brook of Zered" to be Wadi Tarfawiye (now Wadi Ḥafirah) in Jordan, and others suggesting that it is Wadi Sa'idah (Ben-Gad Hacohen, David. – 1998, pp. 21– ff.).

- Text: איגר סהדותה; Apparently the place mentioned in Genesis 31:47, with a slightly different spelling: יְגַר שָׂהֲדוּתָא, meaning "the Heap of Witness."

- A village that is now a ruin in present-day Jordan, located approximately 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) north of the Dead Sea and 16 kilometers (9.9 miles) east of Jericho. The village is also mentioned by Josephus (1981), s.v. The Jewish War 4.7.4–5 (p. 538), as being inhabited by Jewish insurgents during the War with Rome.

- Text: רקם דגיאה, the Aramaic translation in all places for Kadesh-barnea (קדש ברנע), whence the spies were sent to search out the Land of Canaan, near Canaan's southern border. Identified by Eusebius (Onomasticon) and by Jacob Sussmann as being Petra in Arabia, the southernmost extent of the boundary of Israel in the 4th century BCE. See: Sussmann, Jacob (1976), p. 239. Cf. Josephus (1981), s.v. Antiquities 4.7.1. (p. 94), who names five Madianite kings who formerly governed the region, but by the 1st century CE the place had already come under the possession of the Arabs: "Of these there were five: Ochus and Sures, Robees and Ures, and, the fifth, Rekem; the city which bears his name ranks highest in the land of the Arabs and to this day is called by the whole Arabian nation, after the name of its royal founder, Rekeme: it is the Petra of the Greeks" (Loeb Classical Library). Others have identified Kadesh-barnea, not with Petra, but with Ein el Qudeirāt, or what is also called Tell Qudeirāt near Quseimah in the region of the central Negev, now belonging to Egypt (Ben-Gad Hacohen, David (1998), pp. 28–29), arguing that Reḳam (Petra) in Mishnah Gittin was not considered the Land of Israel, while Reḳam of Ǧayāh is listed as a frontier city of the Land of Israel. See also Aharoni, Y. (n.d.), "Kadesh-barnea," Encyclopaedia Biblica, 7:39-42; R. Cohen, "Kadesh-Barnea," New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavation 3:843–847.

- The Jerusalem Talmud (Shevi'it 6:1) says that this place of gardens was situated north of the city of Ashkelon, and that Ashkelon itself was considered outside the boundaries of Israel held by those returning from the Babylonian exile.

- Ben-Gad Hacohen, David (1998), p. 25, has suggested that this expanse of territory extended from Ashkelon as far as Zoar, on the southeastern shore of the Dead Sea, passing in a southeasterly direction as far as Tell Qudeirāt before turning eastward toward the Akrabbim pass and thence to Ein Haṣeba, and continuing northeast to the southern end of the Dead Sea.