History of Xinjiang

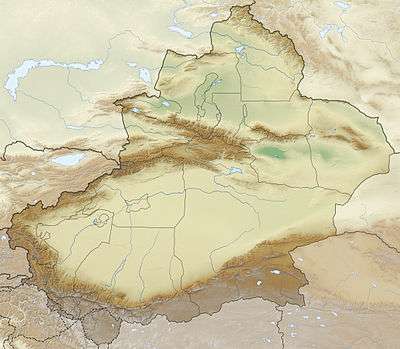

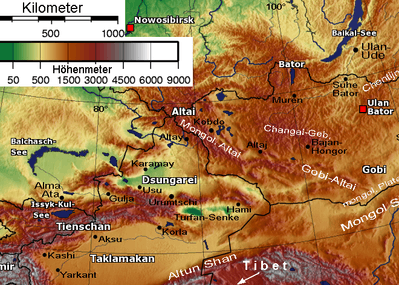

The History of Xinjiang concerns two main geographically, historically, and ethnically distinct regions with different historical names: Dzungaria north of the Tianshan Mountains; and the Tarim Basin south of the Tianshan Mountains, currently mainly inhabited by the Uyghurs. They were renamed Xinjiang (新疆) in 1884, meaning "new frontier," when both regions were reconquered by the Chinese Qing dynasty after the Dungan revolt (1862–1877).

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Xinjiang |

|

|

Medieval and early modern period |

The first inhabitants came from the west.[1] The oldest Tarim mummies, found in the Tarim Basin, are dated to the 2nd millennium BCE, when the Indo-European Tocharians inhabited the Tarim Basin. In the first millennium BCE the Tarim Basin was inhabited by the Indo-European Yuezhi nomads. In the second century BCE the region became part of the Xiongnu empire, a confederation of nomads centered on present-day Mongolia.

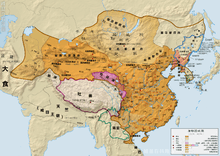

The Tarim Basin was first referred to as "Xiyu" (Chinese: 西域) under the Han dynasty, which drove the Xiongnu out of the Tarim Basin in 60 BCE (Han–Xiongnu War) in an effort to build and secure the profitable Silk Road,[2] maintaining a variable military presence until the early 3rd century CE. From the 2nd to the 5th century local rulers controlled the region. In the 6th century, the First Turkic Khaganate was established. In the 7th-8th century Tang, Turks and Tibetans warred for control, and the Tang dynasty established the Anxi Protectorate of Xinjiang and Central Asia.

This was followed by the Uyghur Khaganate in the 8th-9th century. Uyghur power declined, and three main regional kingdoms vied for power around Xinjiang, namely the Buddhist Uyghur Kara-Khoja, the Turkic Muslim Kara-Khanid, and the Iranian Buddhist Khotan. Eventually, the Turkic Muslim Kara-Khanids prevailed and Islamized the region. In the 13th century it was part of the Mongol Empire. After that, the Turkic people prevailed again.

In the 18th century, the area was conquered by the Chinese Qing dynasty. In 1884, after the Dungan Revolt (1862–77), the area was renamed Xinjiang. It is now a part of the People's Republic of China, despite resistance of the local population.

Etymology

Xinjiang consists of two main geographically, historically, and ethnically distinct regions with different historical names: Dzungaria north of the Tianshan Mountains; and the Tarim Basin south of the Tianshan Mountains.

In ancient China, the Tarim Basin was known as "Xiyu" or "Western Regions", a name that became prevalent in Chinese records after the Han Dynasty took control of the region in the 2st century BCE.[2][3] It soon was traversed by the Northern Silk Road.[4]

For the Uyghurs, who took control of northern Xinjiang in the 8th century, the traditional name of the Tarim Basin in southern Xinjiang was Altishahr, which means "six cities" in the Uyghur language. The region of Dzungaria in northern Xinjiang was named after its native inhabitants, the Dzungar Mongols.

The name "East Turkestan" was created by the Russian Sinologist Nikita Bichurin to replace the term "Chinese Turkestan" in 1829,[5] both being used to refer to the Tarim Basin.

In 1759 the Qing China conquered the region. In 1884 Qing China, after the Dungan revolt (1862–1877), unified Dzungaria and the Tarim Basin into one political entity called Xinjiang (新疆) or roughly "New border", which was used to refer to any area of former Chinese empires that had been previously lost but was regained by the Qing. Eventually it came to mean this northwestern Xinjiang alone.[6] In the Uyghur language, Xinjiang is considered more central than northwestern in orientation.[7] In the late 19th century, there was a proposal to restore the old administration of Xinjiang into two provinces, the areas north and south of Tianshan. It was never adopted.[8]

Ethnic identity

At the time of the Qing conquest in 1759, Dzungaria was inhabited by steppe dwelling, nomadic Tibetan Buddhist Oirat Mongol Dzungar people, while the Tarim Basin was inhabited by sedentary, oasis dwelling, Turkic speaking Muslim farmers, now known as the Uyghur people. They were governed separately until 1884.

The Qing dynasty was well aware of the differences between the former Buddhist Mongol area to the north of the Tianshan and Turkic Muslim south of the Tianshan, and ruled them in separate administrative units at first.[9] However, Qing people began to think of both areas as part of one distinct region called Xinjiang.[10] The very concept of Xinjiang as one distinct geographic identity was created by the Qing, and it was originally not the native inhabitants who viewed it that way.[11] During Qing rule, there was not much sense of "regional identity" held by ordinary Xinjiang people. Rather, Xinjiang's distinct identity was given by the Qing. It had distinct geography, history, and culture, while at the same was still Chinese territory, settled by Han and Hui, distinct from the rest of Central Asia, and largely multicultural.[12]

Genetic studies

The modern Uyghurs are now a mixed hybrid of East Eurasian and West Eurasian.[13][14][15] James A. Millward described the original Uyghurs as physically Mongoloid, giving as an example the images in Bezeklik at temple 9 of the Uyghur patrons, until they began to mix with the Tarim Basin's eastern Iranian inhabitants.[16]

Studies show that modern Uyghurs descend from both Turkic Uyghurs and the pre-Turkic Tocharians (Yuezhi), and that relatively fair hair and eyes (i.e. blonde hairs and blue eyes) are not uncommon among Uyghurs either (not exclusively Western Eurasian). Genetic analyses suggest West Eurasian (West Asian and Persian) maternal contribution to Uyghurs is 42.6% and the paternal between 43.9% and 61.2%. The estimation of total Western Asian component in modern Uyghur population ranged from 30 to 60%.[17]

Li et al. (2010) analyzed the remains of Xiaohe individuals found at the Xiaohe Tomb complex (2nd millennium BCE) for Y-DNA and mtDNA markers. The study found that while Y-DNA corresponded to West Eurasian populations, the mtDNA haplotypes were an admixture of East Asian and European origin.[18] The initial admixture may have taken place in Southern Siberia, which was settled by the Indo-European Andronovo and Afanasevo culture.[19]

Local inhabitants at Sampul cemetery (Shanpula; 山普拉) around 14 km (8.7 mi), from the archaeological site of Hotan in Lop County,[20] where art such as the Sampul tapestry has been found,[21] buried their dead from roughly 217 BCE to 283 CE.[22] The analysis of mtDNA haplogroup distribution showed that the Sampula inhabitants had a large mixture of East Asian, Persian and European characteristics.[20][23] According to Chengzhi et al. (2007), analysis of maternal mitochondrial DNA of the human remains has revealed genetic affinities at the maternal side to Ossetians and Iranians, an Eastern-Mediterranean paternal lineage.[20][24][note 1]

Early inhabitants (2nd–1st millennium BCE)

Tarim mummies

Well preserved mummies with Caucasoid features, often with reddish or blond hair, have been found in the Tarim Basin, dating from 1800 BCE to the first centuries BCE.[31][32][33] The mummies, particularly the early ones, are frequently associated with the presence of the Indo-European Tocharian languages in the Tarim Basin.[34]

The Shan Hai Jing (4th-2nd century BCE) describes the existence of "white people with long hair" or Bai (白), who lived beyond the northwestern border. These are thought to have referred to the Yuezhi people. According to J. P. Mallory and Victor H. Mair, "[s]uch a description could accord well with a Caucasoid population beyond the frontiers of Ancient China," possibly the Yuezhi.[35]

Mallory and Mair relate the earliest Bronze Age settlers of the Tarim and Turpan basins to the Afanasevo culture. The Afanasevo culture (c. 3500–2500 BCE) displays cultural and genetic connections with the Indo-European-associated cultures of the Eurasian Steppe yet predates the specifically Indo-Iranian-associated Andronovo culture (c. 2000–900 BCE) enough to isolate the Tocharian languages from Indo-Iranian linguistic innovations like satemization.[36] Han Kangxin, who examined the skulls of 302 mummies, found the closest relatives of the earlier Tarim Basin population in the populations of the Afanasevo culture situated immediately north of the Tarim Basin and the Andronovo culture that spanned Kazakhstan and reached southwards into West Central Asia and the Altai.[37]

Victor H. Mair's team concluded that the mummies are Caucasoid, likely speakers of Indo-European languages such as the Tocharians:[38][39]:p. 40

From the evidence available, we have found that during the first 1,000 years after the Loulan Beauty, the only settlers in the Tarim Basin were Caucasoid. East Asian peoples only began showing up in the eastern portions of the Tarim Basin about 3,000 years ago, Mair said, while the Uighur peoples arrived after the collapse of the Orkon Uighur Kingdom, largely based in modern day Mongolia, around the year 842.[38][40]

Physical anthropologists propose the movement of at least two Caucasian physical types into the Tarim Basin. Mallory and Mair associate these types with the Tocharian and Iranian (Saka) branches of the Indo-European language family, respectively.[41] However, archaeology and linguistics professor Elizabeth Wayland Barber cautions against assuming the mummies spoke Tocharian, noting a gap of about a thousand years between the mummies and the documented Tocharians: "people can change their language at will, without altering a single gene or freckle."[42] Hemphill & Mallory (2004) confirm a second Caucasian physical type at Alwighul (700–1 BCE) and Krorän (200 CE) different from the earlier one found at Qäwrighul (1800 BCE) and Yanbulaq (1100–500 BCE). Mallory and Mair associate this later (700 BCE – 200 CE) Caucasian physical type with the populations who introduced the Iranian Saka language to the western part of the Tarim basin.[43]

Yuezhi

Various nomadic tribes, such as the Yuezhi, Saka, and Wusun are conjectured to be part of the migration of Indo-European speakers who were settled in Central Asia at that time. The Ordos culture (6th to 2nd centuries BCE) in northern China east of the Yuezhi, whose excavated skeletal remains have been predominantly Mongoloid.

The first reference to the nomadic Yuezhi was in 645 BC by Guan Zhong in his Guanzi (Guanzi Essays: 73: 78: 80: 81). He described the Yuzhi (禺氏), or Niuzhi (牛氏), as a people from the north-west who supplied jade to the Chinese from the nearby mountains of Yuzhi (禺氏) at Gansu.[44][note 2]

The nomadic tribes of the Yuezhi are documented in Chinese historical accounts, in particular the 2nd–1st century BC "Records of the Great Historian", or Shiji, by Sima Qian.[note 3] According to Han accounts, the Yuezhi "were flourishing" during the time of the first great Chinese Qin emperor, but were regularly in conflict with the neighboring Xiongnu tribe to the northeast.

Xiongnu rule and Chinese military protectorate (2nd c. BCE – 2nd c. CE)

This is the beginning of what Millward calls the 'classical period.'[48] In the 20th century, China changed many of the place names of Xinjiang back to the original Chinese names of 2000 years earlier. They saw this as a patriotic act restoring the greatness and borders of the Han dynasty.[48] Millward notes that from a 'modern nationalist perspective' the Han unified the Chinese empire, at least its furthest western extents.[48]

The Han expansion into Xinjiang is well supported by 'rich' textual sources and the material evidence, from archaeological artifacts excavated in the Taklamakan Desert and trade items across Eurasia.[48] These point to the influence of Chinese culture and Han settlements in the region, and the exchange of luxury items between China, India, and the west lends credence to the view that Xinjiang was the center of Silk Road trade.[48]

Xiongnu (2nd–1st c. BCE)

At the beginning of the Han dynasty (206 BC – AD 220), the region was subservient to the Xiongnu, a powerful nomadic people based in modern Mongolia. The Xiongnu were a tribal confederation[49] of nomadic peoples who, according to ancient Chinese sources, inhabited the eastern Eurasian Steppe from the 3rd century BC to the late 1st century AD. Chinese sources report that Modu Chanyu, the supreme leader after 209 BC, founded the Xiongnu Empire.[50]

In 209 BC, three years before the founding of Han China, the Xiongnu were brought together in a powerful confederation under a new chanyu, Modu Chanyu. This new political unity transformed them into a more formidable state by enabling formation of larger armies and the ability to exercise better strategic coordination. After their previous rivals, the Yuezhi, migrated into Central Asia during the 2nd century BC, the Xiongnu became a dominant power on the steppes of north-east Central Asia, centered on an area known later as Mongolia. The Xiongnu were also active in areas now part of Siberia, Inner Mongolia, Gansu and Xinjiang. Their relations with adjacent Chinese dynasties to the south east were complex, with repeated periods of conflict and intrigue, alternating with exchanges of tribute, trade, and marriage treaties (heqin).

The reason for creating the confederation remains unclear. Suggestions include the need for a stronger state to deal with the Qin unification of China[51] that resulted in a loss of the Ordos region at the hands of Meng Tian or the political crisis that overtook the Xiongnu in 215 BC when Qin armies evicted them from their pastures on the Yellow River.[52]

After forging internal unity, Modu Chanyu expanded the empire on all sides. To the north he conquered a number of nomadic peoples, including the Dingling of southern Siberia. He crushed the power of the Donghu people of eastern Mongolia and Manchuria as well as the Yuezhi in the Hexi Corridor of Gansu, where his son, Jizhu, made a skull cup out of the Yuezhi king. Modu also reoccupied all the lands previously taken by the Qin general Meng Tian.

Under Modu's leadership, the Xiongnu threatened the Han dynasty, almost causing Emperor Gaozu, the first Han emperor, to lose his throne in 200 BC. By the time of Modu's death in 174 BC, the Xiongnu had driven the Yuezhi from the Hexi Corridor, killing the Yuezhi king in the process and asserting their presence in the Western Regions.

Han penetrations and military protectorate (1st c. BCE – 2nd c. CE)

.png)

.svg.png)

In 139 BCE the Emperor Wu of Han dispatched the former palace attendant Zhang Qian to form an alliance with the Yuezhi people in order to combat the Xiongnu. He was captured by the Xiongnu, and held prisoner for a decade. After his return, his knowledge of the lands of the west was the main information the Han had of this region.[53] Between 133 BCE and 89 CE, the Hand and the Xiongnu fought a series of battles, known as the Han–Xiongnu War.

In 102 BC the Han defeated Dayuan, who had not been willing to supply the Han with Ferghana horses, in the War of the Heavenly Horses. After a series of victories against the Xiongnu, the Chinese penetrated the strategic region from the Ordos and Gansu corridor as far as Lop Nor.[53] Between 120 BCE and 60 BCE, fighting between Han and Xiongnu continued.[53] At that time, the Tarim Basin was inhabited by various peoples, including Tocharians (in Turfan and Kucha) and Indo-Iranian Saka peoples around Kashgar and Khotan.[54]

In 60 BC Han China established the Protectorate of the Western Regions at Wulei (烏壘; near modern Luntai) to oversee the Tarim Basin as far west as the Pamir. The Tarim Basin and Indo-European kingdoms were controlled through military colonies by the Han dynasty, but the Han "never had a foothold in Zungharia (northern Xinjiang), which the Xiongnu and the Wusun dominated for this whole period."[55][note 4]

During Wang Mang's usurpation (8–25 CE), and the civil war in the central Han territory, the Han left the Tarim basin, and the Northern Xiongnu re-established their overlordship.[56] At the end of the 1st century, Han China conducted several expeditions into the region, re-establishing militaru colonies "and bullied the Tarim city-states into renewing their vow of allegiance to Han,"[56] from 74–76 and 91–107. From 107 to 125 the Han left the Tarim Basin again, leaving it to the Xiongnu.[56] From 127 to c.150 it was controlled again by the Han, whereafter the Tocharian-speaking Kushan Empire (30-375) took control of the western and northern Tarim Basin.[56][57] The Kushan played a role in introducing Buddhism to the Tarim Basin and China, and in translating Buddhist texts into Chinese and other languages.[58][note 5]

Local rule and Turkic expansion (3rd–12th c.)

Local rule (3rd–6th century)

After the fall of the Han dynasty (220), there was "only limited and sporadic involvement in the Tarim Basin" by the Chinese.[59][note 6] During the third and fourth century, the region was ruled by local rulers.[60] Local city-states such as the Kingdom of Khotan (56-1006), Kashgar (Shule Kingdom), Hotan (Yutian), Kucha (Guizi) and Cherchen (Qiemo) controlled the western half, while the central region around Turpan was controlled by Gaochang (later known as Qara-hoja). In the 4th century, Zungharia was occupied by Ruanruan confederation, while the oasis cities south of Tianshan paid tribute to the Ruanruan.[61] From c. 450 to 560 the Tarim Basin was controlled by the Hephthalites (White Huns), until they were defeated in 560 by the Kök Türk.[62]

Gokturk Khaganate and Tuyuhun (5th–7th c.)

In the 5th century the Turks began to emerge in the Altay region, subservient to the Rouran. Within a century they had defeated the Rouran and established a vast Turkic Khaganate (552–581), stretching over most of Central Asia past both the Aral Sea in the west and Lake Baikal in the east. In 581 the Gokturks split into the Western Turkic Khaganate (581–657) and Eastern Turkic Khaganate (581–630), with Xinjiang coming under the western half.

Parts of southern Xinjiang were controlled by the Tuyuhun Kingdom (284–670), who established a vast empire that encompassed Qinghai, Gansu, Ningxia, northern Sichuan, eastern Shaanxi, southern Xinjiang, and most of Tibet, stretching 1,500 kilometers from east to west and 1,000 kilometers from north to south. They unified parts of Inner Asia for the first time in history, developed the southern route of the Silk Road, and promoted cultural exchange between the eastern and western territories, dominating the northwest for more than three and half centuries until it was destroyed by the Tibetan Empire.[63] The Tuyuhun Empire existed as an independent kingdom outside China[64] and was not included as part of Chinese historiography.

Tang, Turks, Tibet, and Arabs (7th–8th c.)

Tang expeditions

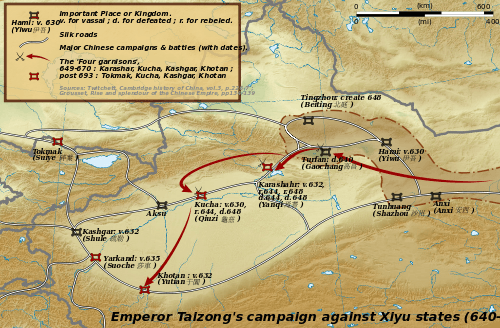

Starting from the 620s and 630s, the Tang dynasty conducted a series of expeditions against the Eastern Turks.[65] By 640, military campaigns were dispatched against the Western Turkic Khaganate, and their vassals, the oasis states of southern Xinjiang.[66] The campaigns against the oasis states began under Emperor Taizong with the annexation of Gaochang in 640.[67] The nearby kingdom of Karasahr was captured by the Tang in 644 and the kingdom of Kucha was conquered in 649.[68]

The expansion into Central Asia continued under Taizong's successor, Emperor Gaozong, who dispatched an army in 657 led by Su Dingfang against the Western Turk qaghan Ashina Helu. Ashina's defeat strengthened Tang rule in southern Xinjiang and brought the regions formerly controlled by the khaganate into the Tang empire.[68] The military expedition included 10,000 horsemen supplied by the Uyghurs, who were close allies of the Tang.[68] The Uyghurs had allied with the Tang ever since the dynasty supported their revolt against the reign of the Xueyantuo, a tribe of Tiele people.[69] Xinjiang was administered through the Anxi Protectorate (安西都護府; '"Protectorate Pacifying the West"') and the Four Garrisons of Anxi.

Unlike the Han dynasty, the Tang ruling house of Li had intermarriages and close affinity to the nomads of the north, due to the establishment of nomadic kingdoms in northern Chibna after the fall of the Han Empire, and the mutual sinication and Turkification of Turkish and Chinese elites. This affinity with the Turks may partly explain why the Tang were able to expand their influence westward into the Tarim Basin, which they ruled indirectly through protectorates and garrisons.[70][71][72]

For five years, Tang suzerainty extended as far west as over Samarkand and Bukhara (Uzbekistan), Kabul and Herat (Afghanistan), and even Zaranj near Iran,[71] but in 662 Tang hegemony beyond the Pamir Mountains in modern Tajikistan and Afghanistan ended with revolts by the Turks. The Tang only retained a military foothold in Beiting.[71]

Tibetan expansion

Tang rule over Xinjiang and Central Asia was threatened by Tibetan expansion into the Southern Tarim.[71] After defeating the Tang in 670, the Tang retreated eastwards "and was in full flight from its empire in Central Asia."[73] The Tibetans subjugated Kashgar in 676-678 and retained possession until 693, when China regained control of southern Xinjiang, and retained it for the next fifty years, though under constant threat from Tibetan and Turkic forces.[74] The Tang were not able to intervere beyond the Pamir Mountains, where Arab forces were moving into Bactria, Ferghana and Soghdiana in the early 8th century, and had no direct influence on the fights bteween Turks, Tibetans and Arabs for control over Central Asia.[75] Tang outposts were repeatedly attacked by Tibetans and the Türgesh, and in 736 Tibet conquered the Pamir regio.[75] In 744 the Tang defeated the Türgesh, and drove the Tibetans out of Pamir.[75] A few years later, war between Ferghana and Tashkent, with the Han supporting Fergahna, resulted in Arab intervention,[75] and in the Battle of Talas (751) the Tang lost to the Abbasid Caliphate, which did not proceed to Xinjiang further into Xinjiang.[76][note 7]

The devastating Anshi Rebellion (755–763) ended Tang presence in the Tarim Basin, when the Tibetan Empire invaded the Tang on a wide front from Xinjiang to Yunnan, sacking the Tang capital Chang'an in 763, and taking control of the southern Tarim.[71]

Sinification and Turkification

According to Millward, "Tang military farms and settlements left an enduring stamp upon local culture and administration in eastern Xinjiang," also leaving "cultural traces in Central Asia and the west," and continued circulation of Chinese coins.[77][note 8] Later Turkic empires gained prestige by associating themselves with north Chinese states established by non-Chinese nomadic people, referring to themselves as "Chinese emperor." "Khitay" was used by the Qara-Khitay, and "Tabghach" was used by the Qarakhanids.[81][note 9] Later Arabian and Persian references to China may actually have referred to Central Asia.[note 10] In Central Asia the Uighurs viewed the Chinese script as "very prestigious" so when they developed the Old Uyghur alphabet, based on the Syriac script, they deliberately switched it to vertical like Chinese writing from its original horizontal position in Syriac.[89]

The Tang presence in Xinjiang also marked the end of Indo-European influence in Xinjiang.[67] This was partially spurred by Chinese policies of using Turkic soldiers, which unintentionally sped the Turkification of Xinjiang,[71] rather than the Sinification that had occurred in other territories conquered by the Tang.[90] The Tang dynasty recruited a large number of Turkic soldiers and generals, and the Chinese garrisons of Xinjiang were for the most part staffed by Turks rather than those of the Han ethnicity. Xinjiang began its transition into a linguistically and culturally Turko-Mongolic region, which continues today.[71] Protected by the Taklamakan Desert from steppe nomads, elements of Tocharian culture survived until the 7th century, when Turkic immigrants from the collapsing Uyghur Khaganate of modern-day Mongolia began to absorb the Tocharians to form the modern-day Uyghur ethnic group.[40]

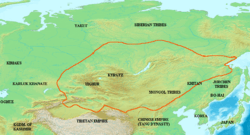

Uyghur Khaganate (8th–9th c.)

In 744 the Uyghur Khaganate (744–840) was formed as a confederation of nine Uyghur clans. The Tang allied with the Uyghur Bayanchur Khan to suppress the An Lushan rebellion, An Lushan himself being from Soghdian-Turkish descend.[91] For their aid, the Tang sent 20,000 rolls of silk and bestowed them with honorary titles. In addition the horse trade was fixed at 40 rolls of silk for every horse and Uyghurs were given "guest" status while staying in Tang China.[92][93] While the Tang thereafter lost their military power in the Tarim, the Uyghurs pressed for control of the eastern basin and Gansu.[91]

In 762 Tengri Bögü planned to invade the Tang with 4,000 soldiers, but after negotiations switched sides, and assisted them in defeating the An Lushan rebels at Luoyang. For their aid, the Tang was forced to pay 100,000 pieces of silk to get the Uyghurs to leave.[94] During the campaign Khagan Tengri Bögü encountered Persian Manichaean priests, and converted Manichaeism, adopting it as the official religion of the Uyghur Khaganate.[95]

In 779 Tengri Bögü, adviced by Sogdian courtiers, planned to invade Tang China, but was killed by his uncle Tun Bagha Tarkhan, who opposed this plan and ascended the throne.[96][97] During his reign Manichaeism was suppressed, but his successors restored it as the official religion.[97]

In 790 the Uyghurs and Tang forces were defeated by the Tibetans at Ting Prefecture (Beshbalik).[98] In 803 the Uyghurs captured Qocho.[99] In 808 the Uyghurs seized Liang Prefecture from the Tibetans.[100] In 822 the Uyghurs sent troops to help the Tang in quelling rebels. The Tang refused the offer but had to pay them 70,000 pieces of silk to go home.[101]

In 840, the Kyrgyz tribe invaded from the north with a force of around 80,000 horsemen, destroying the Uyghur capital at Ordu Baliq and other cities, and killing the Uyghur Khagan, Kürebir (Hesa). The last legitimate khagan, Öge, was assassinated in 847, having spent his 6-year reign in fighting the Kyrgyz and the supporters of his rival Ormïzt, a brother of Kürebir. After the fall of the Uyghur Khaganate, the Uyghurs migrated south and established the Ganzhou Uyghur Kingdom in modern Gansu[102] and the Kingdom of Qocho near modern Turpan. The Uyghurs in Qocho converted to Buddhism, and, according to Mahmud al-Kashgari, were "the strongest of the infidels" while the Ganzhou Uyghurs were conquered by the Tangut people in the 1030s.[103]

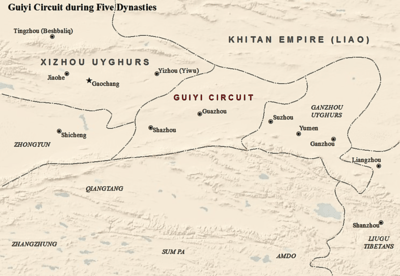

Regional kingdoms (9th c.)

Both Tibet and the Uyghur Khanate declined in the mid-9th century. There were three main regional kingdoms that vied for power in and around Xinjiang: the Persian Buddhist Kingdom of Khotan (56–1006); the Buddhist Uyghur Qocho (Kara-Khoja), founded by Uyghurs who migrated southwards;and the Turkic Muslim Kara-Khanid, which eventually conquered the whole Tarim Basin. The Turkic Qarakhanid and Uyghur Qocho Kingdoms were both states founded by invaders, while the native populations of the region were Iranian, Tocharian, Chinese (Qocho), and Indian. They married and mixed with the Turkic invaders.

Iranian Buddhist Khotan (56–1006)

Iranian Saka peoples originally inhabited Yarkand and Kashgar in ancient times. They formed the Buddhist Kingdom of Khotan (56–1006). Its ruling family used Indian names and the population were devout Buddhists. The Buddhist entitles of Dunhuang and Khotan had a tight-knit partnership, with intermarriage between Dunhuang and Khotan's rulers and Dunhuang's Mogao grottos and Buddhist temple funded and sponsored by the Khotan royals, depicted in the Mogao grottoes.[104] In the Mogao caves, the rulers of Khotan hired artists to paint divine figures alongside the Khotans to give them strength against their Turkic rivals.

Buddhist-Manichean Western Uyghur kingdom Qocho (Kara-Khoja) (843 – mid 14th c.)

In 840, after the Uyghur Khanate in Mongolia had been conquered by the Kirghiz, Uyghurs migrated southwards into the Tarim Basin, to Kara-khoja and to Beshbalik near today's Turpan and Urumqi. They formed the Western Uyghur Kingdom Qocho (Kara-Khoja Kingdom), which remained in eastern Xinjiang until the 14th century, though it was subject to various overlords during that time, including the Karakhanid. The Uyghur state in eastern Xinjiang was initially Manicheaean, but later converted to Buddhism. Analysis of Tarim mummies confirms that Turkic-speaking Uighur began migrating to the region by the 9th century (842 CE) from Central Asia.[108]

Iranian monks maintained a Manichaean temple in the Kingdom, but the Tang military presence in Qocho and Turfan also left traces upon the Buddhist Uyghur Kingdom of Qocho. The Persian Hudud al-'Alam uses the name "Chinese town" to refer to Qocho, the capital of the Uyghur kingdom, and Tang names were kept in use for more than 50 Buddhist temples, with Emperor Tang Taizong's edicts stored in the "Imperial Writings Tower," and Chinese dictionaries like Jingyun, Yuian, Tang yun, and da zang jing (Buddhist scriptures) stored inside the Buddhist temples.[109] The Turfan Buddhist Uighurs of the Kingdom of Qocho continued to produce the Chinese Qieyun rime dictionary and developed their own pronunciations of Chinese characters, left over from the Tang influence over the area.[110]

The modern Uyghur linguist Abdurishid Yakup pointed out that the Turfan Uyghur Buddhists studied the Chinese language and used Chinese books like Qianziwen (the thousand character classic) and Qieyun *(a rime dictionary).[111]

Turkic Muslim Kara-Khanids (840–1212)

Around the 9th century the Kara-Khanid Khanate rose from a confederation of Turkic tribes living in Semirechye (modern Kazakhstan), Western Tian Shan (modern Kyrgyzstan), and Western Xinjiang (Kashgaria).[112] They later occupied Transoxania. The Karakhanids were made up mainly of the Karluks, Chigils and Yaghma tribes. The capital of Karakhanid Khanate was Balasaghun on the Chu River and then later Samarkand and Kashgar.

The Kara-Khanids converted to Islam. Their administrative language was Middle Chinese, though Persian, Arabic, and Turkic were also spoken.

In a series of wars, the Karakhanid conquered Khotan. In 966, Sultan Satuq Bughra Khan of the Kara-Khandids converted to Islam after contacts with the Muslim Samanid Empire. He then launched Karakhanid invasions of Khotan cities east of Kashgar.[113]

Halfway into the 10th century, Karakhanid ruler Musa again attacked Khotan. The Karakhanid general Yusuf Qadir Khan finally conquered Khotan around 1006, thereby beginning the Turkification and Islamicization of the region.[104][114]

After Yusuf's conquest of Altishahr, he adopted the title "King of the East and China".[115]

Bughra Khan was overthrown by his nephew Satuq. The Arslan Khans were also toppled and Balasaghun taken by Satuq, with the conversion of the Qarakhanid Turk population to Islam following Satuq's accession to power. With the spread of Islam the Qarakhanid Turks conquered Transoxiana from the Arabs and the Samanids from the Persians.[116]

Islamization of Xinjiang

The majority of the Turks converted to Islam in the mid 10th century under Sultan Satuq Bughra Khan when they established the Kara-Khanid Khanate.[117][118][119][120][121][122] Satuq Bughra Khan and his son directed endeavors to proselytize Islam among the Turks and engage in military conquests.[123] Dunhuang's Cave 17, which contained Khotanese literary works, was shut possibly after its caretakers heard that Khotan's Buddhist buildings were being razed by the Muslims. Buddhism then ceased to exist in Khotan.[124]

The Imams who helped Yusuf were assassinated by the Buddhists prior to the last Muslim victory. So Yusuf assigned Khizr Baba, born in Khotan but whose mother originated from Western Turkestan's Mawarannahr, to take care of the shrine of the four Imams at their tomb. Due to the Imam's death in battle and burial in Khotan, Altishahr, and despite their foreign origins, the Kara-khanids are viewed as local saints by the current Hui people in the region.[115]

The Karakhanid also converted the Uyghurs. Prominent Qarakhanids such as Mahmud Kashghari hold a high position among modern Uyghurs.[125] Kashghari viewed the least Persianified Turkic dialects as the "purest" and "the most elegant".[126]

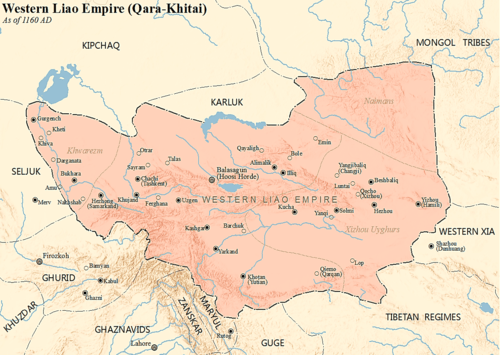

Western Liao (1124–1218)

In 1124 the Khitan people, nomadic people from northeast Asia, led by Yelü Dashi and the royal family marched from Kedun to establish the Qara Khitai in Central Asia. The migration included Han Chinese, Bohai, Jurchen, Mongol tribes, the Xiao consort clan, etc.[127] Some Khitans migrated into western areas even before.[128] In 1132, further remnants of the Liao dynasty from Manchuria and North China entered Xinjiang, fleeing the onslaught of the Jurchens into North China. They established an exile regime, the Qara Khitai, which became overlord over both Kara-Khanid held and Uyghur held parts of the Tarim Basin for the next century. During the Liao, many Han Chinese lived in Kedun, situated in present-day Mongolia.[129]

In 1208, a Naiman prince named Kuchlug fled his homeland after being defeated by the Mongols. He fled westward to the Qara Khitai, where he became an advisor. However, he rebelled three years later and usurped the throne of Qara Khitai. His regime proved to be short-lived however because the Mongols under Genghis Khan would soon invade Central Asia including the Qara Khitai.

The Qara-Khitai empire retained Chinese characteristics in their state to appeal to the Muslim Central Asians and legitimize Khitai rule.[130] This was because China had a good reputation among the Muslims, who viewed China as extremely civilized, with their unique script (hanzi), expert artisans, legal system, justice and religious tolerance. These were among the virtues attributed to the Chinese despite their idol worship. At the time, the Turkic, Arab, Byzantine, Indian rulers, and the Chinese emperor were known as the world's "five great kings." The memory of Tang China was so engraved into the Muslim perception that they continued to view China through the lens of the Tang. Anachronisms appeared in Muslim writings even after the end of the Tang.[131]

Mongol-Turkic Khanates (12th–18th c.)

Mongol Empire and Chagatai Khanate (1225–1340s)

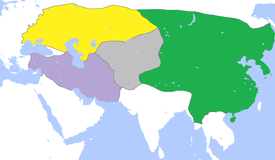

* Golden Horde (yellow)

* Chagatai Khanate (gray)

* Great Yuan−Yuan Dynasty (green)

* Ilkhanate (purple).

In 1206 Genghis Khan unified the Mongol and Turkic tribes on the Mongolian plateau, estanblishing the Mongol Empire (1206–1368). In 1209, after they began their advance west, the Uyghur state in the Turfan-Urumqi area offered its allegiance to the Mongol Empire. It paid taxes and sent troops to fight for the Mongol imperial effort and work as civil servants. In return, the Uyghur rulers retained control of their kingdom. In 1218, Genghis captured Qara Khitai.

After the dead of Möngke Khan in 1259, the Mongol Empire was divided into four khanates. In 1271 the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) was founded by Kublai Khan and based in modern-day Beijing, but lost control of the Tarim Basin and Zungharia to Ariq Böke, ruler of Mongolia.[132]

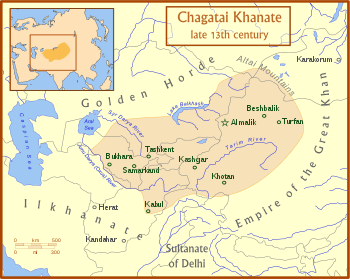

Chagatai Khanate (1225–1340s)

The Chagatai Khanate was a Mongol and later Turkicized khanate[133][134] that comprised the lands ruled by Chagatai Khan,[135] second son of Genghis Khan, and his descendants and successors. Initially it was a part of the Mongol Empire, but it became a functionally separate khanate with the fragmentation of the Mongol Empire after 1259. The Chagatai Khanate recognized the nominal supremacy of the Yuan dynasty in 1304,[136] but became split into two parts in the mid-14th century: the Western Chagatai Khanate and the Moghulistan Khanate.

Chagatai's grandson Alghu (1260–1266) took advantage of the Toluid Civil War (1260-1264) between Kublai Khan and Ariq Böke by revolting against the latter, seizing new territories and gaining the allegiance of the Great Khan's authorities in Transoxiana.[137] Most of the Chagatayids first supported Kublai but in 1269 they joined forces with the House of Ögedei.[138]

After the Kaidu–Kublai war (1268–1301) between the Yuan and Chagatai Khanate (led by Kaidu), most of Xinjiang was controlled by the Chagatai Khanate (1225–1340s). This lasted until the mid-14th century, when Chagatai split into the Western Chagatai Khanate (1340s–1370) and Moghulistan (1340s–1680s), also called the Eastern Chagatai Khanate.

Buddhism survived in Uyghurstan (Turfan and Qocho) during the Ming dynasty (1368 to 1644).[139]

The Buddhist Uyghurs of the Kingdom of Qocho and Turfan were converted to Islam by conquest during a ghazat (holy war) at the hands of the Muslim Chagatai Khizr Khwaja, Khan of Moghulistan during the Chagatai Khanate (reign 1390-1399).[140]

Kara Del (c. 1389–1513) was a Mongolian-ruled and Uighur-populated Buddhist kingdom. The Muslim Chagatai Khan Mansur invaded and "used the sword" to make the population convert to Islam.[141]

After being converted to Islam, the descendants of the previously Buddhist Uyghurs in Turfan failed to retain memory of their ancestral legacy and falsely believed that the "infidel Kalmuks" (Dzungars) were the ones who built Buddhist monuments in their area.[142][143]

During the Mongol Empire, more Han Chinese moved into Besh Baliq, Almaliq and Samarqand in Central Asia to work as artisans and farmers.[144] The Liao Chinese traditions helped the Qara Khitai avoid Islamization.[145] They continued to use Chinese as the administrative language.

Moghulistan (Eastern Chagatai Khanate)(1462–1680s)

.png)

After the death of Qazan Khan in 1346, the Chagatai Khanate, which embraced both East and West Turkestan, was divided into Transoxiana (west) and Moghulistan (east, controlling parts of Xinjiang). Power in the western half devolved into the hands of several tribal leaders, most notably the Qara'unas. Khans appointed by the tribal rulers were mere puppets.

In the east, Tughlugh Timur (1347–1363), a Chaghataite adventurer, defeated the nomadic Mongols and converted to Islam. During his rein (until 1363), the Moghuls converted to Islam and slowly Turkified. In 1360, and again in 1361, Timur invaded the western half in the hope that he could reunify the khanate. At their height, the Chaghataite domains extended from the Irtysh River in Siberia down to Ghazni in Afghanistan, and from Transoxiana to the Tarim Basin.

Moghulistan occupied the settled lands of Eastern Turkestan as well as nomad lands north of Tengri tagh. The settled lands were known at the time as Manglai Sobe or Mangalai Suyah, which translates as "Shiny Land" or "Advanced Land that faced the Sun." These included west and central Tarim oasis-cities, such as Khotan, Yarkand, Yangihisar, Kashgar, Aksu, and Uch Turpan; and hardly involved eastern Tangri Tagh oasis-cities, such as Kucha, Karashahr, Turpan and Kumul, where a local Uyghur administration and Buddhist population still existed. The nomadic areas comprised present-day Kyrgyzstan and parts of Kazakhstan, including Jettisu, the area of seven rivers.

Moghulistan existed around 100 years and then split into two parts: 1) Yarkand state (mamlakati Yarkand), with its capital at Yarkand, which embraced all the settled lands of Eastern Turkestan; and 2) nomadic Moghulistan, which embraced the nomad lands north of Tengri Tagh. The founder of Yarkand was Mirza Abu-Bakr, who was from the Dughlat tribe. In 1465, he raised a rebellion, captured Yarkand, Kashgar, and Khotan, and declared himself an independent ruler, successfully repelling attacks by the Moghulistan rulers Yunus Khan and his son Akhmad Khan (or Ahmad Alaq, named Alach, "Slaughterer", for his war against the Kalmyks).

Dughlat amirs had ruled the country that lay south of the Tarim Basin from the middle of the thirteenth century, on behalf of Chagatai Khan and his descendants, as their satellites. The first Dughlat ruler, who received lands directly from the hands of Chagatai, was amir Babdagan or Tarkhan. The capital of the emirate was Kashgar, and the country was known as Mamlakati Kashgar. Although the emirate, representing the settled lands of Eastern Turkestan, was formally under the rule of the Moghul khans, the Dughlat amirs often tried to put an end to that dependence, and raised frequent rebellions, one of which resulted in the separation of Kashgar from Moghulistan for almost 15 years (1416–1435). Mirza Abu-Bakr ruled Yarkand for 48 years.[146]

Yarkand Khanate (1514–1705)

In May, 1514, Sultan Said Khan, grandson of Yunus Khan (ruler of Moghulistan between 1462 and 1487) and third son of Ahmad Alaq, made an expedition against Kashgar from Andijan with only 5000 men, and having captured the Yangi Hissar citadel, that defended Kashgar from south road, took the city, dethroning Mirza Abu-Bakr. Soon after, other cities of Eastern Turkestan — Yarkant, Khotan, Aksu, and Uch Turpan — joined him, and recognized Sultan Said Khan as ruler, creating a union of six cities, called Altishahr. Sultan Said Khan's sudden success is considered to be contributed to by the dissatisfaction of the population with the tyrannical rule of Mirza Abu-Bakr and the unwillingness of the dughlat amirs to fight against a descendant of Chagatai Khan, deciding instead to bring the head of the slain ruler to Sultan Said Khan. This move put an end to almost 300 years of rule (nominal and actual) by the Dughlat Amirs in the cities of West Kashgaria (1219–1514). He made Yarkand the capital of a state, "Mamlakati Yarkand" which lasted until 1678.

The Khojah Kingdom

In the 17th century, the Dzungars (Oirats, Kalmyks) established an empire over much of the region. Oirats controlled an area known as Grand Tartary or the Kalmyk Empire to Westerners, which stretched from the Great Wall of China to the Don River, and from the Himalayas to Siberia. A Sufi master Khoja Āfāq defeated Saidiye kingdom and took the throne at Kashgar with the help of the Oirat (Dzungar) Mongols. After Āfāq's death, the Dzungars held his descendants hostage. The Khoja dynasty rule in the Altishahr (Tarim Basin) region lasted until 1759.

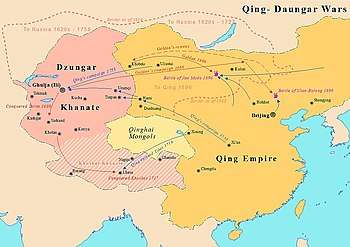

Dzungar Khanate (1634–1758)

The Mongolian Dzungar (also Zunghar; Mongolian: Зүүнгар Züüngar) was the collective identity of several Oirat tribes that formed and maintained one of the last nomadic empires, the Dzungar Khanate. The Dzungar Khanate covered the area called Dzungaria and stretched from the west end of the Great Wall of China to present-day eastern Kazakhstan, and from present-day northern Kyrgyzstan to southern Siberia. Most of this area was only renamed "Xinjiang" by the Chinese after the fall of the Dzungar Empire. It existed from the early 17th century to the mid-18th century.

The Turkic Muslim sedentary people of the Tarim Basin were originally ruled by the Chagatai Khanate while the nomadic Buddhist Oirat Mongol in Dzungaria ruled over the Dzungar Khanate. The Naqshbandi Sufi Khojas, descendants of the Prophet Muhammad, had replaced the Chagatayid Khans as the ruling authority of the Tarim Basin in the early 17th century. There was a struggle between two factions of Khojas, the Afaqi (White Mountain) faction and the Ishaqi (Black Mountain) faction. The Ishaqi defeated the Afaqi, which resulted in the Afaqi Khoja inviting the 5th Dalai Lama, the leader of the Tibetan Buddhists, to intervene on his behalf in 1677. The 5th Dalai Lama then called upon his Dzungar Buddhist followers in the Dzungar Khanate to act on this invitation. The Dzungar Khanate then conquered the Tarim Basin in 1680, setting up the Afaqi Khoja as their puppet ruler.

Khoja Afaq asked the 5th Dalai Lama when he fled to Lhasa to help his Afaqi faction take control of the Tarim Basin (Kashgaria).[147] The Dzungar leader Galdan was then asked by the Dalai Lama to restore Khoja Afaq as ruler of Kashgararia.[148] Khoja Afaq collaborated with Galdan's Dzungars when the Dzungars conquered the Tarim Basin from 1678-1680 and set up the Afaqi Khojas as puppet client rulers.[149][150][151] The Dalai Lama blessed Galdan's conquest of the Tarim Basin and Turfan Basin.[152]

67,000 patman (each patman is 4 piculs and 5 pecks) of grain 48,000 silver ounces were forced to be paid yearly by Kashgar to the Dzungars and cash was also paid by the rest of the cities to the Dzungars. Trade, milling, and distilling taxes, corvée labor, saffron, cotton, and grain were also extracted by the Dzungars from the Tarim Basin. Every harvest season, women and food had to be provided to Dzungars when they came to extract the taxes from them.[153]

When the Dzungars levied the traditional nomadic Alban poll tax upon the Muslims of Altishahr, the Muslims viewed it as the payment of jizyah (a tax traditionally taken from non-Muslims by Muslim conquerors).[154]

After being converted to Islam, the descendants of the previously Buddhist Uyghurs in Turfan failed to retain memory of their ancestral legacy and falsely believed that the "infidel Kalmuks" (Dzungars) were the ones who built Buddhist monuments in their area.[142][143]

Manchu Qing conquest and local revolts (18th–20th century)

Dzungar–Qing Wars (1687–1757) and revolts (1757–1866)

The Dzungars lost control of Dzungari and the Tarim Basin to the Manchu Qing dynasty as a result of the Dzungar–Qing Wars (1687–1757). Between 1755 and 1760 the Qing Qianlong Emperor finally conquered the Dzungarian plateau and the Tarim Basin, bringing the two separate regions, respectively north and south of the Tianshan mountains, under his rule as Xinjiang.[155] The south was inhabited by Turkic Muslims (Uyghurs) and the north by Dzungar Mongols,[156] also called "Eleuths" or "Kalmyks".

In 1755, the Qing Empire attacked Ghulja, and captured the Dzungar Khan. Over the next two years, the Manchus and Mongol armies of the Qing destroyed the remnants of the Dzungar Khanate, and attempted to divide the Xinjiang region into four sub-Khanates under four chiefs. Similarly, the Qing made members of a clan of Sufi shaykhs known as the Khojas, rulers in the western Tarim Basin, south of the Tianshan Mountains.

After Oirat nobel Amursana's request to be declared Dzungar khan went unanswered, he led a revolt against the Qing. Qing attention became temporarily focused on the Khalka prince Chingünjav, a descendant of Genghis Khan, who between the summer of 1756 and January 1757 mounted the most serious Khalka Mongol rebellion against the Qing until its demise in 1911. Before dealing with Amursana, the majority of Qianlong's forces were reassigned to ensure stability in Khalka until Chingünjav's army was crushed by the Qing in a ferocious battle near Lake Khövsgöl in January, 1757.[157] After the victory, Qianlong dispatched additional forces to Ili where they quickly routed the rebels. Amursana escaped for a third time to the Kazakh Khanate, but not long afterwards Ablai Khan pledged tributary status to the Chinese, which meant Amursana was no longer safe.[158] Over the next two years, Qing armies destroyed the remnants of the Dzungar khanate. The Qing Manchu Bannermen carried out the Dzungar genocide (1755-1758) on the native Dzungar Oirat Mongol population, nearly wiping them from existence and depopulating Dzungaria.

The Turkic Muslims of the Turfan and Kumul Oases then submitted to the Qing dynasty of China, and the Qing accepted the rulers of Turfan and Kumul as Qing vassals.

The Qing freed the Afaqi Khoja leader Burhān al-Dīn Khoja and his brother Jahān Khoja from their imprisonment by the Dzungars, and appointed them to rule as Qing vassals over the Tarim Basin. The Khoja brothers decided to renege on this deal, igniting the revolt of the Altishahr Khojas (1757–1759), and declaring themselves as independent leaders of the Tarim Basin. The Qing and the Turfan leader Emin Khoja crushed their revolt, and Manchu Qing then took control of both Dzungaria and the Tarim Basin by 1759. For almost one hundred years, the Āfāqi Khojas waged numerous military campaigns as a part of the Āfāqī Khoja Holy War in an effort to retake Altishahr from the Qing.

The Qing tried to consolidate their authority by settling Chinese emigrants, together with a Manchu Qing garrison. The Qing put the whole region under the rule of a General of Ili, headquartered at the fort of Huiyuan (the so-called "Manchu Kuldja", or Yili), 30 km (19 mi)west of Ghulja (Yining).

Ush rebellion (1765)

The Ush rebellion in 1765 by Uyghurs against the Manchus occurred after Uyghur women were gang raped by the servants and son of Manchu official Su-cheng.[159][160][161] It was said that Ush Muslims had long wanted to sleep on [Sucheng and son's] hides and eat their flesh. because of the rape of Uyghur Muslim women for months by the Manchu official Sucheng and his son.[162] The Manchu Emperor ordered that the Uyghur rebel town be massacred, the Qing forces enslaved all the Uyghur children and women and slaughtered the Uyghur men.[163] Manchu soldiers and Manchu officials regularly having sex with or raping Uyghur women caused massive hatred and anger by Uyghur Muslims to Manchu rule. The invasion by Jahangir Khoja was preceded by another Manchu official, Binjing who raped a Muslim daughter of the Kokan aqsaqal from 1818–1820. The Qing sought to cover up the rape of Uyghur women by Manchus to prevent anger against their rule from spreading among the Uyghurs.[164]

Qing governance

Qing legitimization by appeal to Han and Tang precedents

The Mancu Qing belonged to the Manchu people, one of the Tungusic peoples, whose language is related to Turkic and Mongolic. They identified their state as "China" (中國), and referred to it as "Dulimbai Gurun" in Manchu. The Qing equated the lands of the Qing state (including present-day Manchuria, Dzungaria in Xinjiang, Mongolia, and other areas) as "China" in both the Chinese and Manchu languages, defining China as a multi-ethnic state. The Qianlong Emperor compared his achievements with that of the Han and Tang ventures into Central Asia to gain prestige and legitimization.[165]

Qianlong's conquest of Xinjiang was driven by his mindfulness of the examples set by the Han and Tang[166] Qing scholars who wrote the official Imperial Qing gazetteer for Xinjiang made frequent references to the Han and Tang era names of the region.[167] The Qing conqueror of Xinjiang, Zhao Hui, is ranked for his achievements with the Tang dynasty General Gao Xianzhi and the Han dynasty Generals Ban Chao and Li Guangli.[168]

Both Han and Tang models for ruling Xinjiang provided some precedence for the Qing, but their style og go ernance mostly resembled that of nomadic powers like the Qara Khitay, and the centralized European and Russian empires.[169]

The Qing portrayed their conquest of Xinjiang in official works as a continuation and restoration of the Han and Tang accomplishments in the region, mentioning the previous achievements of those dynasties.[170] The Qing justified their conquest by claiming that the Han and Tang era borders were being restored,[171] and identifying the Han and Tang's grandeur and authority with the Qing.[172]

Many Manchu and Mongol Qing writers who wrote about Xinjiang did so in the Chinese language, from a culturally Chinese point of view.[173] Han and Tang era stories about Xinjiang were recounted, and ancient Chinese places names were reused and circulated.[174] Han and Tang era records and accounts of Xinjiang were the only writings on the region available to Qing era Chinese in the 18th century and needed to be replaced with updated accounts by the literati.[156][173]

Migration-politics in Dzungaria

After Qing dynasty defeated the Dzungar Oirat Mongols, the Qing settled Han, Hui, Manchus, Xibe, and Taranchis (Uyghurs) from the Tarim Basin, into Dzungaria. Han Chinese criminals and political exiles were exiled to Dzungaria, such as Lin Zexu. Hui Muslims and Salar Muslims belonging to banned Sufi orders like the Jahriyya were also exiled to Dzhungaria. After crushing the 1781 Jahriyya rebellion, the Qing exiled Jahriyya adherents too.

Han and Hui merchants were initially only allowed to trade in the Tarim Basin. Han and Hui settlement in the Tarim Basin was banned until the 1830 Muhammad Yusuf Khoja invasion, after which the Qing rewarded the merchants for fighting off Khoja by allowing them to settle down.[175]

In 1870, there were many Chinese of all occupations living in Dzungaria, and they were well settled in the area, while in Turkestan (Tarim Basin) there were only a few Chinese merchants and soldiers in several garrisons among the Muslim population.[176][177]

At the start of the 19th century, 40 years after the Qing reconquest, there were around 155,000 Han and Hui Chinese in northern Xinjiang and somewhat more than twice that number of Uyghurs in southern Xinjiang.[178]

Dungan Revolt (1862–1877)

Reclaiming the Tarim Basin

Yakub Beg ruled Kashgaria at the height of the Great Game era when the British, Russian, and Manchu Qing empires were all vying for Central Asia. Kashgaria extended from the capital Kashgar in south-western Xinjiang to Ürümqi, Turfan, and Hami in central and eastern Xinjiang more than a thousand kilometers to the north-east, including a majority of what was known at the time as East Turkestan.[179]

They remained under his rule until December 1877 when General Zuo Zongtang (also known as General Tso) reconquered the region in 1877 for Qing China. In 1881, Qing recovered the Gulja region through diplomatic negotiations in the Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1881).

In 1884, Qing China renamed the conquered region, established Xinjiang (新疆; '"new frontier"') as a province, formally applying onto it the political system of China proper. The two previously separate regions,

- Dzungaria, known as Zhunbu (準部), Tianshan Beilu (天山北路; 'Northern March'),[180][181][182]

- The Tarim Basin, which had been known as Altishahr, Huibu (Muslim region), Huijiang (Muslim-land) or "Tianshan Nanlu" (天山南路; 'Southern March'),[183][184] were combined into a single province called Xinjiang in 1884.[185] Before this, there was never one administrative unit in which North Xinjiang (Zhunbu) and Southern Xinjiang (Huibu) were integrated together.[186] Dzungaria's alternate name is 北疆 (Běijiāng; 'North Xinjiang') and Altishahr's alternate name is 南疆 (Nánjiāng; 'South Xinjiang').[187]

After Xinjiang was converted into a province by the Qing, the provincialization and reconstruction programs initiated by the Qing resulted in the Chinese government helping Uyghurs migrate from southern Xinjiang to other areas of the province, like the area between Qitai and the capital, formerly nearly completely inhabited by Han Chinese, and other areas like Urumqi, Tacheng (Tabarghatai), Yili, Jinghe, Kur Kara Usu, Ruoqiang, Lop Nor, and the Tarim River's lower reaches.[188] It was during Qing times that Uyghurs were settled throughout all of Xinjiang, from their original home cities in the western Tarim Basin.

Turki-Russian clash quelled by the Qing

An anti-Russian uproar broke out when Russian customs officials, three Cossacks and a Russian courier invited local Turki Muslim prostitutes to a party in January 1902 in Kashgar. This caused a massive brawl between the inflamed local Turki Muslim populace against the Russians on the pretense of protecting Muslim women because of swelling anti-Russian sentiment. Even though morality was not strict in Kashgar, the local Turki Muslims violently clashed with the Russians before they were dispersed. The Chinese sought to end to tensions to prevent the Russians from using this as a pretext to invade.[189][190][191]

After the riot, the Russians sent troops to Sarikol in Tashkurghan and demanded that the Sarikol postal services be placed under Russian supervision. The locals of Sarikol believed that the Russians would seize the entire district from the Chinese and send more soldiers even after the Russians tried to negotiate with the Begs of Sarikol and sway them to their side. They failed since the Sarikoli officials and authorities demanded in a petition to the Amban of Yarkand that they be evacuated to Yarkand to avoid being harassed by the Russians. They also objected to the Russian presence in Sarikol, as the Sarikolis did not believe Russian claims that they would leave them alone and were only involved in mail service.[192][193]

Education

Mosques ran the schools (or maktab مكتب in Arabic).[194][195] Madrasas and mosques were where most education took place. The Madrasas taught poetry, logic, syntax, Arabic grammar, Islamic law, the Quran, but not much history.[196][197][198]

The Jadidists Turkic Muslims from Russia spread new ideas on education.[199][200][201][202][203][204] Between the 1600s and 1900s many Turki language tazkirah texts were written.[205]

Indian-produced literature in the Persian language was exported to Kashgar.[206][207]

Chinese books were also popular among Uyghurs.[208] Kashgar's earliest printed work was translated by Johannes Avetaranian. He helped in producing the Turki language version of the Shung-chi Emperor's work.[209] The "Sacred Edict" by the Kangxi Emperor was released in both Turki and Chinese when printed in Xinjiang by Zuo Zongtang.[210] One of the Shunzhui Emperor's literary works was rendered into Turki and published in Kashgar by Nur Muhammad.[211] Various attempts at publishing and printing were attempted.[212][213]

Population

Starting 1760, the Qing dynasty gave large amounts of land to Chinese Hui Muslims and Han Chinese who settled in Dzungaria, while Turkic Muslim Taranchis were also moved into Dzungaria in the Ili region from Aqsu. In the following 60 years, the population of the Tarim Basin swelled to twice its original size during Qing rule.

No permanent settlement was allowed in the Tarim Basin, with only merchants and soldiers being allowed to stay temporarily.[214]

To the 1830s after Jahangir's invasion, Altishahr was open to Han and Hui settlement. Then 19th century rebellions caused the Han population to drop. The demonym "East Turkestan" was used for the area consisting of Uyghuristan (Turfan and Hami) in the northeast and Altishahr or Kashgaria in the southwest.

Various estimates were given by foreign visitors on the entire region's population.

| Year | Population | Notes and sources |

|---|---|---|

| Beginning of Qing c.1650 | 260K (Altishahr) | the population was concentrated more towards Kucha's western region |

| 1900 | 1.015, 1.2, or 2.5 M | Kuropatkin,[215] Forsyth, Grennard;[216] other estimates show 300K living in Alitshahr; Uyghuristan in the east had 10% while Kashgaria had 70% of the population.[217] |

| 1920 | 1.5M | Percy Sykes: Almost entirely confined to oases, chiefly Kashgar 300K, Yangi Shahr 200K, Yarkand 200K, and Aksu and Khotan each with 190K inhabitants. The population may be grouped into " settled " and " nomadic," with a small semi-nomadic division. The nomads, together with the semi-nomads, do not aggregate more than 125K in all.[218] |

| 1922 | 2-3, or 5M | Yang Zengxin[216] |

| 1931 | 6-8M | [216] |

| 1933+ | 2,900,173 Uyghurs, ?? Han, ?? other | [219] |

| 1941 | 3,730,000 | Toops: 65,000 Kirghiz, 92,000 Hui, 326,000 Kazakh, 187,000 Han, and 2,984,000 Uyghur[220]

3,439,000 of which were Muslims; 2,941,000 of those Muslims were Uyghurs (1940s)[221] Jean Bowie Shor wrote that there were 3,000,000 Uigurs and gave 3,500,000 as the total number of residents in Xinjiang.[222] |

| 1949 | 4,334,000 | Hoppe[220] |

Republic of China and East Turkistan Republics (1912–1949)

In 1912 the Qing dynasty was replaced by the Republic of China. Yuan Dahua, the last Qing governor of Xinjiang, fled to Siberia. One of his subordinates Yang Zengxin, acceded to the Republic of China in March of the same year, and maintained control of Xinjiang until his assassination in 1928.

The name "Altishahr and Zungharia",[223] "Altisheher-Junghar",[224] "Altishähär-Junghariyä"[225] were used to refer to the region.

The ROC era in Xinjiang saw the rise of East Turkestan separatist movements.

Oirat rebellions

Legends grew and prophecies circulated among the remaining Oirats that Amursana had not died after he fled to Russia, but was alive and would return to his people to liberate them from Manchu Qing rule and restore the Oirat nation.[226][227]

The Oirat Kalmyk Ja Lama claimed to be a grandson of Amursana and then claimed to be a reincarnation of Amursana himself, preaching anti-Manchu propaganda in western Mongolia in the 1890s and calling for the overthrow of the Qing dynasty.[228] Ja Lama was arrested and deported several times. However, in 1910 he returned to the Oirat Torghuts in Altay (in Dzungaria), and in 1912 he helped the Outer Mongolians mount an attack on the last Qing garrison at Kovd, where the Manchu Amban was refusing to leave and fighting the newly declared independent Mongolian state.[229][230][231][232][233][234] The Manchu Qing force was defeated and slaughtered by the Mongols after Khovd fell.[235][236]

Ja Lama told the Oirat remnants in Xinjiang: "I am a mendicant monk from the Russian Tsar's kingdom, but I am born of the great Mongols. My herds are on the Volga river, my water source is the Irtysh. There are many hero warriors with me. I have many riches. Now I have come to meet with you beggars, you remnants of the Oirats, in the time when the war for power begins. Will you support the enemy? My homeland is Altai, Irtysh, Khobuk-sari, Emil, Bortala, Ili, and Alatai. This is the Oirat mother country. By descent, I am the great-grandson of Amursana, the reincarnation of Mahakala, owning the horse Maralbashi. I am he whom they call the hero Dambijantsan. I came to move my pastures back to my own land, to collect my subject households and bondservants, to give favour, and to move freely."[237][238]

Ja Lama built an Oirat fiefdom centered on Kovd,[239] he and fellow Oirats from Altai wanted to emulate the original Oirat empire and build another grand united Oirat nation from the nomads of western China and Mongolia,[240] but was arrested by Russian Cossacks and deported in 1914 on the request of the Mongolian government after the local Mongols complained of his excesses, and out of fear that he would create an Oirat separatist state and divide them from the Khalkha Mongols.[241] Ja Lama returned in 1918 to Mongolia and resumed his activities and supported himself by extorting passing caravans,[242][243][244] but was assassinated in 1922 on the orders of the new Communist Mongolian authorities under Damdin Sükhbaatar.[245][246][247]

Mongolian separatism

Mongols have at times advocated for the historical Oirat Dzungar Mongol area of Dzungaria in northern Xinjiang to be annexed to the Mongolian state in the name of Pan-Mongolism.

In 1918 the part Buryat Mongol Transbaikalian Cossack Ataman Grigory Semyonov declared a "Great Mongol State" and had designs to unify the Oirat Mongol lands, portions of Xinjiang, Transbaikal, Inner Mongolia, Outer Mongolia, Tannu Uriankhai, Khovd, Hu-lun-pei-erh and Tibet into one.[248]

The Buryat Mongol Agvan Dorzhiev tried advocating for Oirat Mongol areas like Tarbagatai, Ili, and Altai to get added to the Outer Mongolian state.[249] Out of concern that China would be provoked, this proposed addition of the Oirat Dzungaria to the new Outer Mongolian state was rejected by the Soviets.[250]

Uyghur violence against Christians and Hindus

Uyghur Muslims rioted against Indian Hindu traders when the Hindus attempted to practice their religious affairs in public. They Uyghurs also attacked the Swedish Christian mission in 1907.[251]

An anti-Christian mob broke out among the Muslims in Kashgar against the Swedish missionaries in 1923.[252]

In the name of Islam, the Uyghur leader Abdullah Bughra violently physically assaulted the Yarkand-based Swedish missionaries and would have executed them, except they were only banished due to the British Aqsaqal's intercession in their favor.[253]

During the 1930s Kumul Rebellion in Xinjiang, Buddhist murals were deliberately vandalized by Muslims.[254]

Xinjiang wars (1933–1945)

First East Turkistan Republic

Following insurgencies against Governor Jin Shuren in the early 1930s, a rebellion in Kashgar led to the establishment of the short-lived First East Turkistan Republic (First ETR) in 1933. The ETR claimed authority around the Tarim Basin from Aksu in the north to Khotan in the south, and was suppressed by the armies of the Chinese Muslim warlord Ma Zhongying in 1934.

Second East Turkistan Republic

Sheng invited a group of Chinese Communists to Xinjiang including Mao Zedong's brother Mao Zemin, but in 1943, fearing a conspiracy against him, Sheng killed all the Chinese Communists, including Mao Zemin. In the summer of 1944, during the Ili Rebellion, a Second East Turkistan Republic (Second ETR) was established, this time with Soviet support, in what is now Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture in northern Xinjiang.

The Three Districts Revolution, as it is known in China, threatened the Nationalist provincial government in Ürümqi. Sheng Shicai fell from power and Zhang Zhizhong was sent from Nanjing to negotiate a truce with the Second ETR and the USSR. An uneasy coalition provincial government was formed and brought nominal unity to Xinjiang with separate administrations.

The coalition government came to an end at the conclusion of the Chinese Civil War when the victorious Chinese Communists entered Xinjiang in 1949. The leadership of the Second ETR was persuaded by the Soviet Union to negotiate with the Chinese Communists. Most were killed in an airplane crash en route to a peace conference in Beijing in late August. The remaining leadership under Saifuddin Azizi agreed to join the newly founded People's Republic of China. The Nationalist military commanders in Xinjiang, Tao Zhiyue and provincial governor Burhan Shahidis surrendered to the People's Liberation Army (PLA) in September. Kazak militias under Osman Batur resisted the PLA into the early 1950s. The Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of the PRC was established on 1 October 1955, replacing Xinjiang Province.

Intermarriages between Han and Uyghurs

In Urumqi (Uyghur) Muslim women who married Han Chinese men were assaulted, seized, and kidnapped by hordes of (Uyghur) Muslims on 11 July 1947. Old (Uyghur) Muslim men forcibly married the women. In response to the chaos a curfew was placed at 11 p.m.[255]

The marriages between Muslim (Uyghur) women and Han Chinese men infuriated the Uyghur leader Isa Yusuf Alptekin.[256]

Mixed Han-Uyghur partners were pressured to leave their parents and sometimes Xinjiang entirely. During the Republic era from 1911 to 1949, Han military generals were pursued and wooed by Uyghur women. In 1949 when the Communists took over, the Uyghur population branded such women as milliy munapiq (ethnic scum), threatening and coercing them in accompanying their Han partners in moving to Taiwan and "China proper." Uyghur parents warned such women not to return any of their children, male or female, to Xinjiang after moving to "China proper" for attending educational institutions. This was so they could avoid ostracism and condemnation from their fellow Uyghurs. A case where a Han male dating a Uyghur woman and then a Han man and her elder sister incited the Uyghur community to condemn and harass her mother.[257]

People's Republic of China and Xinjiang conflict (1949–present)

Takeover by the People's Liberation Army

During the Ili Rebellion the Soviet Union backed Uyghur separatists to form the Second East Turkistan Republic (2nd ETR) from 1944 to 1949 in what is now Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture (Ili, Tarbagatay and Altay Districts) in northern Xinjiang while the majority of Xinjiang was under Republic of China Kuomintang control.[258] The People's Liberation Army entered Xinjiang in 1949 and the Kuomintang commander Tao Zhiyue surrendered the province to them.[259]

According to the PRC, the 2nd ETR was Xinjiang's revolution, a positive part of the communist revolution in China; the 2nd ETR acceded to and 'welcomed' the PLA when it entered Xinjiang, a process known as the Incorporation of Xinjiang into the People's Republic of China.

Uyghur nationalists often incorrectly claim that 5% of Xinjiang's population in 1949 was Han, and that the other 95% was Uyghur, erasing the presence of Kazakhs, Xibes, etc., and ignoring the fact that Hans were around one third of Xinjiang's population at 1800, during the Qing Dynasty.[260]

The autonomous region was established on 1 October 1955.[259] In 1955 (the first modern census in China was taken in 1953), Uyghurs were counted as 73% of Xinjiang's total population of 5.11 million.[261] Although Xinjiang as a whole is designated as a "Uyghur Autonomous Region", since 1954 more than 50% of Xinjiang's land area are designated autonomous areas for 13 native non-Uyghur groups.[262] The modern Uyghur people experienced ethnogenesis especially since 1955, when the PRC officially recognized their ethnic category—distinct from the Han—of formerly separately self-identified oasis peoples.[263]

The PRC's first nuclear test was carried out at Lop Nur, Xinjiang, on 16 October 1964. Japanese physicist Jun Takada, known for prominently opposing the tests as "the Devil's conduct" speculated that between 100,000 and 200,000 people may have been killed due to the consequential radiation. According to the Scientific American article, Jun Takada was not allowed into China. Moreover, he 'studied radiation effects from tests conducted by the U.S., the former Soviet Union and France'.[264] However the Lop Nur area has not been permanently inhabited since the 1920s.[265] This is because it is located between the Taklamakan and Kumtag deserts in Ruoqiang County, which has an area of almost 200,000 km2 (77,000 sq mi) with a population density of only 0.16/km2. Furthermore, Chinese media rejected Takada's conclusion.[266]

Han migration into the region

The PRC has stimulated Han migration into the sparsely populated Dzungaria (Dzungar Basin). Before 1953 most of Xinjiang's population (75%) lived in the Tarim Basin, so the new Han migrants changed the distribution of population between Dzungaria and the Tarim.[267][268][269] Most new Chinese migrants ended up in the northern region Dzungaria.[270] Han and Hui made up the majority of the population in Dzungaria's cities while Uighurs made up most of the population in the Tarim's Kashgarian cities.[271] Eastern and Central Dzungaria are the specific areas where these Han and Hui are concentrated.[272]

Xinjiang conflict

The Xinjiang conflict is a conflict in China's far-west province of Xinjiang centred around the Uyghurs, a Turkic minority ethnic group who make up the largest group in the region.[273][274]

Factors such as the massive state-sponsored migration of Han Chinese from the 1950s to the 1970s, government policies promoting Chinese cultural unity and punishing certain expressions of Uyghur identity,[275][276] and heavy-handed responses to separatist terrorism[277][278] have contributed to tension between Uyghurs, and state police and Han Chinese.[279] This has taken the form of both frequent terrorist attacks and wider public unrest (such as the July 2009 Ürümqi riots).

In recent years, government policy has been marked by mass surveillance, increased arrests, and a system of "re-education camps", estimated to hold hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs and members of other Muslim minority groups.[280][281][note 12]

Uyghur nationalism

Uyghur nationalist historians such as Turghun Almas claim that Uyghurs were distinct and independent from Chinese for 6000 years, and that all non-Uyghur peoples are non-indigenous immigrants to Xinjiang.[282] This constructed history was so successful, that China ceased publishing Uyghur historiography in 1991.[283] Chinese historians state that the region was 'multicultural' since ancient times,[284] refuting Uyghur nationalist claims by pointing out the 2,000-year history of Han settlement in Xinjiang, documenting the history of Mongol, Kazakh, Uzbek, Manchu, Hui, Xibo indigenes in Xinjiang, and by emphasizing the relatively late "westward migration" of the Huigu (equated with "Uyghur" by the PRC government) people from Mongolia the 9th century.[282][285][286]

Yet, Bovingdon notes that both Uygur and Chinese narratives do not accord with the historical facts and developments, which are complex and interwoven, noting that the Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD) established military colonies (tuntian) and commanderies (duhufu) to control Xinjiang from 120 BC, while the Tang dynasty (618–907) also controlled much of Xinjiang until the An Lushan rebellion.[287] In the 9th century, after the fall of the Uyghur Khanate, the Uyghurs migrated to Xinjiang from the area encompassed by Mongolia, Inner Mongolia, and Siberia,[284] having originated from the 'Mongolian core lands of the Orkhon river valley'.[288][289][290][291] The name "Uyghur" originally was associated with a Buddhist people in the Tarim Basin in the 9th century, but completely disappeared by the 15th century, until it was revived by the Soviet Union in the 20th century.[292]

Bovingdon notes that China faces similar problems in constructing a narrative that has to fill gaps in the desired historical record.[293]

Soviet support during Cold war

The Soviet Union supported Uyghur nationalist propaganda and Uyghur separatist movements against China. The Soviets incited separatist activities in Xinjiang through propaganda, encouraging Kazakhs to flee to the Soviet Union and attack China. China responded by reinforcing the Xinjiang-Soviet border area specifically with Han Bingtuan militia and farmers.[294] Since 1967 the Soviets intensified their broadcasts inciting Uyghurs to revolt against the Chinese via Radio Tashkent and directly harbored and supported separatist guerilla fighters to attack the Chinese border. In 1966 the number of Soviet sponsored separatist attacks on China numbered 5,000.[295]

After the Sino-Soviet split in 1962, over 60,000 Uyghurs and Kazakhs defected from Xinjiang to the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic, in response to Soviet propaganda which promised Xinjiang independence. Uyghur exiles later threatened China with rumors of a Uyghur "liberation army" in the thousands that were supposedly recruited from Sovietized emigres.[296]

In 1968 the Soviet Union was involved in funding and supporting the East Turkestan People's Revolutionary Party (ETPRP), the largest militant Uyghur separatist organization in its time, to start a violent uprising against China.[297][298][299][300][301] In the 1970s, the Soviets also supported the United Revolutionary Front of East Turkestan (URFET) to fight against the Chinese.[302]

In 1966-67 "bloody incidents" flared up as Chinese and Soviet forces clashed along the border. The Soviets trained anti-Chinese guerillas and urged Uyghurs to revolt against China, hailing their "national liberation struggle".[303] In 1969, Chinese and Soviet forces directly fought each other along the Xinjiang-Soviet border.[304][305][306][307]

A chain of aggressive and belligerent press releases in the 1990s making false claims about violent insurrections in Xinjiang, and exaggerating both the number of Chinese migrants and the total number of Uyghurs in Xinjiang were made by the former Soviet supported URFET leader Yusupbek Mukhlisi.[308][309]

Chinese response

Xinjiang's importance to China increased after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, leading to China's perception of being encircled by the Soviets.[310] The Chinese supported the Afghan mujahideen during the Soviet invasion, and broadcast reports of Soviet atrocities on Afghan Muslims to Uyghurs in order to counter Soviet propaganda broadcasts into Xinjiang, which boasted that Soviet minorities lived better and incited Muslims to revolt.[311] Chinese radio beamed anti-Soviet broadcasts to Central Asian ethnic minorities like the Kazakhs.[304]

The Soviets feared disloyalty among the non-Russian Kazakh, Uzbek, and Kyrgyz in the event of Chinese troops attacking the Soviet Union and entering Central Asia. Russians were goaded with the taunt "Just wait till the Chinese get here, they'll show you what's what!" by Central Asians when they had altercations.[312]

The Chinese authorities viewed the Han migrants in Xinjiang as vital to defending the area against the Soviet Union.[313] China opened up camps to train the Afghan Mujahideen near Kashgar and Khotan and supplied them with hundreds of millions of dollars worth of small arms, rockets, mines, and anti-tank weapons.[314][315]

Incidents

Since the late 1970s Chinese economic reform exacerbated uneven regional development, more Uyghurs have migrated to Xinjiang cities and some Hans have also migrated to Xinjiang for independent economic advancement. Increased ethnic contact and labor competition coincided with Uyghur separatist terrorism from the 1990s, such as the 1997 Ürümqi bus bombings.[316]

After a number of student demonstrations in the 1980s, the Baren Township riot of April 1990 led to more than 20 deaths.[317]

1997 saw the Ghulja Incident and Urumqi bus bombs,[318] while police continue to battle with religious separatists from the East Turkestan Islamic Movement.

Recent incidents include the 2007 Xinjiang raid,[319] a thwarted 2008 suicide bombing attempt on a China Southern Airlines flight,[320] and the 2008 Xinjiang attack which resulted in the deaths of sixteen police officers four days before the Beijing Olympics.[321][322] Further incidents include the July 2009 Ürümqi riots, the September 2009 Xinjiang unrest, and the 2010 Aksu bombing that led to the trials of 376 people.[323] In 2013 and 2014 a series of attacks on railway stations and a market, which claimed the lives of 70 people, and wounded hundreds more, resulted in a 12-month government clampdown. Two mass sentencing trials involving 94 people convicted of terrorism charges, resulted in three receiving death sentences, and the others lengthy jail terms.[324]

Xinjiang re-education camps