Xiongnu

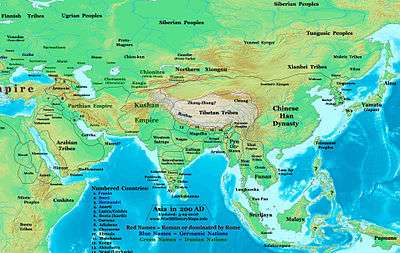

The Xiongnu [ɕjʊ́ŋ.nǔ] (Chinese: 匈奴; Wade–Giles: Hsiung-nu) were a tribal confederation[3] of nomadic peoples who, according to ancient Chinese sources, inhabited the eastern Eurasian Steppe from the 3rd century BC to the late 1st century AD. Chinese sources report that Modu Chanyu, the supreme leader after 209 BC, founded the Xiongnu Empire.[4]

| Xiongnu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 匈奴 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History of Mongolia | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ancient period

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Medieval period

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Modern period

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Xinjiang |

|

|

Medieval and early modern period |

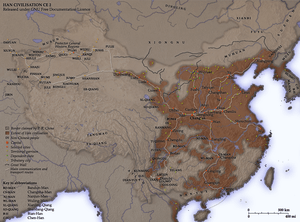

After their previous rivals, the Yuezhi, migrated into Central Asia during the 2nd century BC, the Xiongnu became a dominant power on the steppes of north-east Central Asia, centered on an area known later as Mongolia. The Xiongnu were also active in areas now part of Siberia, Inner Mongolia, Gansu and Xinjiang. Their relations with adjacent Chinese dynasties to the south-east were complex, with repeated periods of conflict and intrigue, alternating with exchanges of tribute, trade, and marriage treaties (heqin).

During the Sixteen Kingdoms era, they were also known as one of the Five Barbarians who took part in an uprising against Chinese rule known as the Uprising of the Five Barbarians.

Attempts to identify the Xiongnu with later groups of the western Eurasian Steppe remain controversial. Scythians and Sarmatians were concurrently to the west. The identity of the ethnic core of Xiongnu has been a subject of varied hypotheses, because only a few words, mainly titles and personal names, were preserved in the Chinese sources. The name Xiongnu may be cognate with that of the Huns or the Huna,[5] although this is disputed.[6][7] Other linguistic links – all of them also controversial – proposed by scholars include Iranian,[8][9][10] Mongolic,[11] Turkic,[12][13] Uralic,[14] Yeniseian,[6][15][16] Tibeto-Burman[17] or multi-ethnic.[18]

History

Early history

An early reference to the Xiongnu was by the Han dynasty historian Sima Qian who wrote about the Xiongnu in the Records of the Grand Historian (c. 100 BC). The ancestor of Xiongnu was a descendent of the rulers of Xia dynasty by the name of Chunwei.[19] It also draws a distinct line between the settled Huaxia people (Chinese) to the pastoral nomads (Xiongnu), characterizing it as two polar groups in the sense of a civilization versus an uncivilized society: the Hua–Yi distinction.[20] Pre-Han sources often classify the Xiongnu as a Hu people, which was a blanket term for nomadic people; it only became an ethnonym for the Xiongnu during the Han.[21]

Ancient China often came in contact with the Xianyun and the Xirong nomadic peoples. In later Chinese historiography, some groups of these peoples were believed to be the possible progenitors of the Xiongnu people.[22] These nomadic people often had repeated military confrontations with the Shang and especially the Zhou, who often conquered and enslaved the nomads in an expansion drift.[22] During the Warring States period, the armies from the Qin, Zhao, and Yan states were encroaching and conquering various nomadic territories that were inhabited by the Xiongnu and other Hu peoples.[23]

Sinologist Edwin Pulleyblank argued that the Xiongnu were part of a Xirong group called Yiqu, who had lived in Shaanbei and had been influenced by China for centuries, before they were driven out by the Qin dynasty.[24] Qin's campaign against the Xiongnu expanded Qin's territory at the expense of the Xiongnu.[25] after the unification of Qin dynasty, Xiongnu was a threat to the northern board of Qin. They were like to attack Qin dynasty when they suffered natural disasters.[26] In 215 BC, Qin Shi Huang sent General Meng Tian to conquer the Xiongnu and drive them from the Ordos Loop, which he did later that year.[27] After the catastrophic defeat at the hands of Meng Tian, the Xiongnu leader Touman was forced to flee far into the Mongolian Plateau.[27] The Qin empire became a threat to the Xiongnu, which ultimately led to the reorganization of the many tribes into a confederacy.[25]

State formation

In 209 BC, three years before the founding of Han China, the Xiongnu were brought together in a powerful confederation under a new chanyu, Modu Chanyu. This new political unity transformed them into a more formidable state by enabling the formation of larger armies and the ability to exercise better strategic coordination. The Xiongnu adopted many of the Chinese agriculture techniques such as slaves for heavy labor, wore silk like the Chinese, and lived in Chinese-style homes.[28] The reason for creating the confederation remains unclear. Suggestions include the need for a stronger state to deal with the Qin unification of China[29] that resulted in a loss of the Ordos region at the hands of Meng Tian or the political crisis that overtook the Xiongnu in 215 BC when Qin armies evicted them from their pastures on the Yellow River.[30]

After forging internal unity, Modu Chanyu expanded the empire on all sides. To the north he conquered a number of nomadic peoples, including the Dingling of southern Siberia. He crushed the power of the Donghu people of eastern Mongolia and Manchuria as well as the Yuezhi in the Hexi Corridor of Gansu, where his son, Jizhu, made a skull cup out of the Yuezhi king. Modu also reoccupied all the lands previously taken by the Qin general Meng Tian.

Under Modu's leadership, the Xiongnu threatened the Han dynasty, almost causing Emperor Gaozu, the first Han emperor, to lose his throne in 200 BC.[31] By the time of Modu's death in 174 BC, the Xiongnu had driven the Yuezhi from the Hexi Corridor, killing the Yuezhi king in the process and asserting their presence in the Western Regions.[5]

The Xiongnu were recognized as the most prominent of the nomads bordering the Chinese Han empire[31] and during early relations between the Xiongnu and the Han, the former held the balance of power. According to the Book of Han, later quoted in Duan Chengshi's ninth century Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang:

Also, according to the Han shu, Wang Wu (王烏) and others were sent as envoys to pay a visit to the Xiongnu. According to the customs of the Xiongnu, if the Han envoys did not remove their tallies of authority, and if they did not allow their faces to be tattooed, they could not gain entrance into the yurts. Wang Wu and his company removed their tallies, submitted to tattoo, and thus gained entry. The Shanyu looked upon them very highly.[32]

Xiongnu hierarchy

After Modu, later leaders formed a dualistic system of political organisation with the left and right branches of the Xiongnu divided on a regional basis. The chanyu or shanyu, a ruler equivalent to the Emperor of China, exercised direct authority over the central territory. Longcheng (蘢城) became the annual meeting place and served as the Xiongnu capital.[33]

The ruler of the Xiongnu was called the Chanyu.[34] Under him were the Tuqi Kings.[34] The Tuqi King of the Left was normally the heir presumptive.[34] Next lower in the hierarchy came more officials in pairs of left and right: the guli, the army commanders, the great governors, the dunghu and the gudu. Beneath them came the commanders of detachments of one thousand, of one hundred, and of ten men. This nation of nomads, a people on the march, was organized like an army.[35]

Yap,[36] apparently describing the early period, places the Chanyu's main camp north of Shanxi with the Tuqi King of the Left holding the area north of Beijing and the Tuqi King of the Right holding the Ordos Loop area as far as Gansu. Grousset,[37] probably describing the situation after the Xiongnu had been driven north, places the Chanyu on the upper Orkhon River near where Genghis Khan would later establish his capital of Karakorum. The Tuqi King of the Left lived in the east, probably on the high Kherlen River. The Tuqi King of the Right lived in the west, perhaps near present-day Uliastai in the Khangai Mountains.

Marriage diplomacy with Han China

In the winter of 200 BC, following a Xiongnu siege of Taiyuan, Emperor Gaozu of Han personally led a military campaign against Modu Chanyu. At the Battle of Baideng, he was ambushed reputedly by Xiongnu cavalry. The emperor was cut off from supplies and reinforcements for seven days, only narrowly escaping capture.

The Han sent princesses to marry Xiongnu leaders in their efforts to stop the border raids. Along with arranged marriages, the Han sent gifts to bribe the Xiongnu to stop attacking.[31] After the defeat at Pingcheng in 200 BC, the Han emperor abandoned a military solution to the Xiongnu threat. Instead, in 198 BC , the courtier Liu Jing was dispatched for negotiations. The peace settlement eventually reached between the parties included a Han princess given in marriage to the chanyu (called heqin) (Chinese: 和親; lit.: 'harmonious kinship'); periodic gifts to the Xiongnu of silk, distilled beverages and rice; equal status between the states; and the Great Wall as mutual border.

This first treaty set the pattern for relations between the Han and the Xiongnu for sixty years. Up to 135 BC, the treaty was renewed nine times, each time with an increase in the "gifts" to the Xiongnu Empire. In 192 BC, Modun even asked for the hand of Emperor Gaozu of Han widow Empress Lü Zhi. His son and successor, the energetic Jiyu, known as the Laoshang Chanyu, continued his father's expansionist policies. Laoshang succeeded in negotiating with Emperor Wen terms for the maintenance of a large scale government sponsored market system.

While the Xiongnu benefited handsomely, from the Chinese perspective marriage treaties were costly, very humiliating, and ineffective. Laoshang Chanyu showed that he did not take the peace treaty seriously. On one occasion his scouts penetrated to a point near Chang'an. In 166 BC he personally led 140,000 cavalry to invade Anding, reaching as far as the imperial retreat at Yong. In 158 BC, his successor sent 30,000 cavalry to attack Shangdang and another 30,000 to Yunzhong.

The Xiongnu also practiced marriage alliances with Han dynasty officers and officials who defected to their side. The older sister of the Chanyu (the Xiongnu ruler) was married to the Xiongnu General Zhao Xin, the Marquis of Xi who was serving the Han dynasty. The daughter of the Chanyu was married to the Han Chinese General Li Ling after he surrendered and defected.[38][39][40][41] Another Han Chinese General who defected to the Xiongnu was Li Guangli, general in the War of the Heavenly Horses, who also married a daughter of the Chanyu.[42]

When the Eastern Jin dynasty ended the Xianbei Northern Wei received the Han Chinese Jin prince Sima Chuzhi 司馬楚之 as a refugee. A Northern Wei Xianbei Princess married Sima Chuzhi, giving birth to Sima Jinlong 司馬金龍. Northern Liang Xiongnu King Juqu Mujian's daughter married Sima Jinlong.[43]

Han-Xiongnu war

The Han dynasty made preparations for war when the Han Emperor Wu dispatched the explorer Zhang Qian to explore the mysterious kingdoms to the west and to form an alliance with the Yuezhi people in order to combat the Xiongnu. During this time Zhang married a Xiongnu wife, who bore him a son, and gained the trust of the Xiongnu leader.[44][45][46][47][48][49][50] While Zhang Qian did not succeed in this mission,[51] his reports of the west provided even greater incentive to counter the Xiongnu hold on westward routes out of China, and the Chinese prepared to mount a large scale attack using the Northern Silk Road to move men and material.

While Han China was making preparations for a military confrontation since the reign of Emperor Wen, the break did not come until 133 BC, following an abortive trap to ambush the chanyu at Mayi. By that point the empire was consolidated politically, militarily and economically, and was led by an adventurous pro-war faction at court. In that year, Emperor Wu reversed the decision he had made the year before to renew the peace treaty.

Full-scale war broke out in autumn 129 BC, when 40,000 Chinese cavalry made a surprise attack on the Xiongnu at the border markets. In 127 BC, the Han general Wei Qing retook the Ordos. In 121 BC, the Xiongnu suffered another setback when Huo Qubing led a force of light cavalry westward out of Longxi and within six days fought his way through five Xiongnu kingdoms. The Xiongnu Hunye king was forced to surrender with 40,000 men. In 119 BC both Huo and Wei, each leading 50,000 cavalrymen and 100,000 footsoldiers (in order to keep up with the mobility of the Xiongnu, many of the non-cavalry Han soldiers were mobile infantrymen who traveled on horseback but fought on foot), and advancing along different routes, forced the chanyu and his Xiongnu court to flee north of the Gobi Desert.[52] Major logistical difficulties limited the duration and long-term continuation of these campaigns. According to the analysis of Yan You (嚴尤), the difficulties were twofold. Firstly there was the problem of supplying food across long distances. Secondly, the weather in the northern Xiongnu lands was difficult for Han soldiers, who could never carry enough fuel.[note 1] According to official reports, the Xiongnu lost 80,000 to 90,000 men, and out of the 140,000 horses the Han forces had brought into the desert, fewer than 30,000 returned to China.

In 104 and 102 BC, the Han fought and won the War of the Heavenly Horses against the Kingdom of Dayuan. As a result, the Han gained many Ferghana horses which further aided them in their battle against the Xiongnu. As a result of these battles, the Chinese controlled the strategic region from the Ordos and Gansu corridor to Lop Nor. They succeeded in separating the Xiongnu from the Qiang peoples to the south, and also gained direct access to the Western Regions. Because of strong Chinese control over the Xiongnu, the Xiongnu became unstable and were no longer a threat to the Han Chinese.[54]

Ban Chao, Protector General (都護; Duhu) of the Han dynasty, embarked with an army of 70,000 soldiers in a campaign against the Xiongnu remnants who were harassing the trade route now known as the Silk Road. His successful military campaign saw the subjugation of one Xiongnu tribe after another. Ban Chao also sent an envoy named Gan Ying to Daqin (Rome). Ban Chao was created the Marquess of Dingyuan (定遠侯, i.e., "the Marquess who stabilized faraway places") for his services to the Han Empire and returned to the capital Luoyang at the age of 70 years and died there in the year 102. Following his death, the power of the Xiongnu in the Western Regions increased again, and the emperors of subsequent dynasties did not reach as far west until the Tang dynasty.[55]

Xiongnu Civil War (60–53 BC)

When a Chanyu died, power could pass to his younger brother if his son was not of age. This system, which can be compared to Gaelic tanistry, normally kept an adult male on the throne, but could cause trouble in later generations when there were several lineages that might claim the throne. When the 12th Chanyu died in 60 BC, power was taken by Woyanqudi, a grandson of the 12th Chanyu's cousin. Being something of a usurper, he tried to put his own men in power, which only increased the number of his enemies. The 12th Chanyu's son fled east and, in 58 BC, revolted. Few would support Woyanqudi and he was driven to suicide, leaving the rebel son, Huhanye, as the 14th Chanyu. The Woyanqudi faction then set up his brother, Tuqi, as Chanyu (58 BC). In 57 BC three more men declared themselves Chanyu. Two dropped their claims in favor of the third who was defeated by Tuqi in that year and surrendered to Huhanye the following year. In 56 BC Tuqi was defeated by Huhanye and committed suicide, but two more claimants appeared: Runzhen and Huhanye's elder brother Zhizhi Chanyu. Runzhen was killed by Zhizhi in 54 BC, leaving only Zhizhi and Huhanye. Zhizhi grew in power, and, in 53 BC, Huhanye moved south and submitted to the Chinese. Huhanye used Chinese support to weaken Zhizhi, who gradually moved west. In 49 BC, a brother to Tuqi set himself up as Chanyu and was killed by Zhizhi. In 36 BC, Zhizhi was killed by a Chinese army while trying to establish a new kingdom in the far west near Lake Balkhash.

Tributary relations with the Han

In 53 BC Huhanye (呼韓邪) decided to enter into tributary relations with Han China.[56] The original terms insisted on by the Han court were that, first, the Chanyu or his representatives should come to the capital to pay homage; secondly, the Chanyu should send a hostage prince; and thirdly, the Chanyu should present tribute to the Han emperor. The political status of the Xiongnu in the Chinese world order was reduced from that of a "brotherly state" to that of an "outer vassal" (外臣). During this period, however, the Xiongnu maintained political sovereignty and full territorial integrity. The Great Wall of China continued to serve as the line of demarcation between Han and Xiongnu.

Huhanye sent his son, the "wise king of the right" Shuloujutang, to the Han court as hostage. In 51 BC he personally visited Chang'an to pay homage to the emperor on the Lunar New Year. In the same year, another envoy Qijushan (稽居狦) was received at the Sweet Spring Palace in the north-west of modern Shanxi.[57] On the financial side, Huhanye was amply rewarded in large quantities of gold, cash, clothes, silk, horses and grain for his participation. Huhanye made two further homage trips, in 49 BC and 33 BC; with each one the imperial gifts were increased. On the last trip, Huhanye took the opportunity to ask to be allowed to become an imperial son-in-law. As a sign of the decline in the political status of the Xiongnu, Emperor Yuan refused, giving him instead five ladies-in-waiting. One of them was Wang Zhaojun, famed in Chinese folklore as one of the Four Beauties.

When Zhizhi learned of his brother's submission, he also sent a son to the Han court as hostage in 53 BC. Then twice, in 51 BC and 50 BC, he sent envoys to the Han court with tribute. But having failed to pay homage personally, he was never admitted to the tributary system. In 36 BC, a junior officer named Chen Tang, with the help of Gan Yanshou, protector-general of the Western Regions, assembled an expeditionary force that defeated him at the Battle of Zhizhi and sent his head as a trophy to Chang'an.

Tributary relations were discontinued during the reign of Huduershi (18 AD–48), corresponding to the political upheavals of the Xin Dynasty in China. The Xiongnu took the opportunity to regain control of the western regions, as well as neighboring peoples such as the Wuhuan. In 24 AD, Hudershi even talked about reversing the tributary system.

Southern Xiongnu and Northern Xiongnu

The Xiongnu's new power was met with a policy of appeasement by Emperor Guangwu. At the height of his power, Huduershi even compared himself to his illustrious ancestor, Modu. Due to growing regionalism among the Xiongnu, however, Huduershi was never able to establish unquestioned authority. In contravention of a principle of fraternal succession established by Huhanye, Huduershi designated his son Punu as heir-apparent. However, as the eldest son of the preceding chanyu, Bi (Pi) – the Rizhu King of the Right – had a more legitimate claim. Consequently, Bi refused to attend the annual meeting at the chanyu's court. Nevertheless, in 46 AD, Punu ascended the throne.

In 48 AD, a confederation of eight Xiongnu tribes in Bi's power base in the south, with a military force totalling 40,000 to 50,000 men, seceded from Punu's kingdom and acclaimed Bi as chanyu. This kingdom became known as the Southern Xiongnu.

The Northern Xiongnu

The rump kingdom under Punu, around the Orkhon (modern north central Mongolia) became known as the Northern Xiongnu. Punu, who became known as the Northern Chanyu, began to put military pressure on the Southern Xiongnu.

In 49 AD, Tsi Yung, a Han governor of Liaodong, allied with the Wuhuan and Xianbei, attacked the Northern Xiongnu.[58] The Northern Xiongnu suffered two major defeats: one at the hands of the Xianbei in 85 AD, and by the Han during the Battle of Ikh Bayan, in 89 AD. The northern chanyu fled to the north-west with his subjects.

In about 155 AD, the Northern Xiongnu were decisively "crushed and subjugated" by the Xianbei.[59]

The Southern Xiongnu

Coincidentally, the Southern Xiongnu were plagued by natural disasters and misfortunes – in addition to the threat posed by Punu. Consequently, in 50 AD, the Southern Xiongnu submitted to tributary relations with Han China. The system of tribute was considerably tightened by the Han, to keep the Southern Xiongnu under control. The chanyu was ordered to establish his court in the Meiji district of Xihe Commandery and the Southern Xiongnu were resettled in eight frontier commanderies. At the same time, large numbers of Chinese were also resettled in these commanderies, in mixed Han-Xiongnu settlements. Economically, the Southern Xiongnu became reliant on trade with the Han.

Tensions were evident between Han settlers and practitioners of the nomadic way of life. Thus, in 94, Anguo Chanyu joined forces with newly subjugated Xiongnu from the north and started a large scale rebellion against the Han.

During the late 2nd century AD, the southern Xiongnu were drawn into the rebellions then plaguing the Han court. In 188, the chanyu was murdered by some of his own subjects for agreeing to send troops to help the Han suppress a rebellion in Hebei – many of the Xiongnu feared that it would set a precedent for unending military service to the Han court. The murdered chanyu's son Yufuluo, entitled Chizhisizhu (持至尸逐侯), succeeded him, but was then overthrown by the same rebellious faction in 189. He travelled to Luoyang (the Han capital) to seek aid from the Han court, but at this time the Han court was in disorder from the clash between Grand General He Jin and the eunuchs, and the intervention of the warlord Dong Zhuo. The chanyu had no choice but to settle down with his followers in Pingyang, a city in Shanxi. In 195, he died and was succeeded as chanyu by his brother Huchuquan Chanyu.

In 215–216 AD, the warlord-statesman Cao Cao detained Huchuquan Chanyu in the city of Ye, and divided his followers in Shanxi into five divisions: left, right, south, north, and centre. This was aimed at preventing the exiled Xiongnu in Shanxi from engaging in rebellion, and also allowed Cao Cao to use the Xiongnu as auxiliaries in his cavalry.

Later the Xiongnu aristocracy in Shanxi changed their surname from Luanti to Liu for prestige reasons, claiming that they were related to the Han imperial clan through the old intermarriage policy. After Huchuquan, the Southern Xiongnu were partitioned into five local tribes. Each local chief was under the "surveillance of a chinese resident", while the shanyu was in "semicaptivity at the imperial court."[60]

Later Xiongnu states in northern China

The Southern Xiongnu that settled in northern China during the Eastern Han dynasty retained their tribal affiliation and political organization and played an active role in Chinese politics. During the Sixteen Kingdoms (304–439 CE), Southern Xiongnu leaders founded or ruled several kingdoms, including Liu Yuan's Han Zhao Kingdom (also known as Former Zhao), Helian Bobo's Xia and Juqu Mengxun's Northern Liang

Fang Xuanling's Book of Jin lists nineteen Xiongnu tribes: Túgè 屠各, Xiānzhī (Fresh Branch) 鮮支, Kòutóu (Thief-Head) 寇頭, Wūtán 烏譚, Chìlè (Red Bridle) 赤勒, Hànzhì 捍蛭, Hēiláng (Black Wolf) 黑狼, Chìshā (Red Sand) 赤沙, Yùgāng 鬱鞞, Wěisuō 萎莎, Tūtóng (Bald Youth) 禿童, Bómiè 勃蔑, Qiāngqú 羌渠, Hèlài 賀賴, Zhōngqīn 鐘跂, Dàlóu (Great Tower) 大樓, Yōngqū 雍屈, Zhēnshù (True Tree) 真樹, Lìjié 力羯.[61]

Former Zhao state (304–329)

- Han Zhao dynasty (304–318)

In 304, Liu Yuan became Chanyu of the Five Hordes. In 308, declared himself emperor and founded the Han Zhao Dynasty. In 311, his son and successor Liu Cong captured Luoyang, and with it the Emperor Huai of Jin China.

In 316, the Emperor Min of Jin China was captured in Chang'an. Both emperors were humiliated as cupbearers in Linfen before being executed in 313 and 318.

North China came under Xiongnu rule while the remnants of the Jin dynasty survived in the south at Jiankang.[62]

- The reign of Liu Yao (318–329)

In 318, after suppressing a coup by a powerful minister in the Xiongnu-Han court, in which the emperor and a large proportion of the aristocracy were massacred), the Xiongnu prince Liu Yao moved the Xiongnu-Han capital from Pingyang to Chang'an and renamed the dynasty as Zhao (Liu Yuan had declared the empire's name Han to create a linkage with Han Dynasty—to which he claimed he was a descendant, through a princess, but Liu Yao felt that it was time to end the linkage with Han and explicitly restore the linkage to the great Xiongnu chanyu Maodun, and therefore decided to change the name of the state. (However, this was not a break from Liu Yuan, as he continued to honor Liu Yuan and Liu Cong posthumously; it is hence known to historians collectively as Han Zhao).

However, the eastern part of north China came under the control of a rebel Xiongnu-Han general of Jie ancestry named Shi Le. Liu Yao and Shi Le fought a long war until 329, when Liu Yao was captured in battle and executed. Chang'an fell to Shi Le soon after, and the Xiongnu dynasty was wiped out. North China was ruled by Shi Le's Later Zhao dynasty for the next 20 years.[63]

However, the "Liu" Xiongnu remained active in the north for at least another century.

Tiefu and Xia (260–431)

The northern Tiefu branch of the Xiongnu gained control of the Inner Mongolian region in the 10 years between the conquest of the Tuoba Xianbei state of Dai by the Former Qin empire in 376, and its restoration in 386 as the Northern Wei. After 386, the Tiefu were gradually destroyed by or surrendered to the Tuoba, with the submitting Tiefu becoming known as the Dugu. Liu Bobo, a surviving prince of the Tiefu fled to the Ordos Loop, where he founded a state called the Xia (thus named because of the Xiongnu's supposed ancestry from the Xia dynasty) and changed his surname to Helian (赫連). The Helian-Xia state was conquered by the Northern Wei in 428–31, and the Xiongnu thenceforth effectively ceased to play a major role in Chinese history, assimilating into the Xianbei and Han ethnicities.

Tongwancheng (meaning "Unite All Nations") was the capital of the Xia (Sixteen Kingdoms), whose rulers claimed descent from Modu Chanyu.

The ruined city was discovered in 1996[64] and the State Council designated it as a cultural relic under top state protection. The repair of the Yong'an Platform, where Helian Bobo, emperor of the Da Xia regime, reviewed parading troops, has been finished and restoration on the 31-meter-tall turret follows.[65][66]

Juqu and Northern Liang (401–460)

The Juqu were a branch of the Xiongnu. Their leader Juqu Mengxun took over the Northern Liang by overthrowing the former puppet ruler Duan Ye. By 439, the Juqu power was destroyed by the Northern Wei. Their remnants were then settled in the city of Gaochang before being destroyed by the Rouran.

Significance

The Xiongnu confederation was unusually long-lived for a steppe empire. The purpose of raiding China was not simply for goods, but to force the Chinese to pay regular tribute. The power of the Xiongnu ruler was based on his control of Chinese tribute which he used to reward his supporters. The Han and Xiongnu empires rose at the same time because the Xiongnu state depended on Chinese tribute. A major Xiongnu weakness was the custom of lateral succession. If a dead ruler's son was not old enough to take command, power passed to the late ruler's brother. This worked in the first generation but could lead to civil war in the second generation. The first time this happened, in 60 BC, the weaker party adopted what Barfield calls the 'inner frontier strategy.' They moved south and submitted to China and then used Chinese resources to defeat the Northern Xiongnu and re-establish the empire. The second time this happened, about 47 AD, the strategy failed. The southern ruler was unable to defeat the northern ruler and the Xiongnu remained divided.[67]

Ethnolinguistic origins

| Pronunciation of 匈 Source: http://starling.rinet.ru | |

|---|---|

| Preclassic Old Chinese: | sŋoŋ |

| Classic Old Chinese: | [ŋ̊oŋ] |

| Postclassic Old Chinese: | hoŋ |

| Middle Chinese: | xöuŋ |

| Modern Mandarin: | [ɕjʊ́ŋ] |

The Chinese name for the Xiongnu was a pejorative term in itself, as the characters (匈奴) have the meaning of "fierce slave".[33] (The Chinese characters are pronounced as Xiōngnú [ɕjʊ́ŋnǔ] in modern Mandarin Chinese.)

There are several theories on the ethnolinguistic identity of the Xiongnu.

Huns

The sound of the first Chinese character (匈) in the name has been reconstructed as /qʰoŋ/ in Old Chinese.[68] This sound has a possible similarity with the name "Hun" in European languages. The second character (奴) means slave and appears to have no parallel in Western terminology. Whether the similarity is evidence of kinship or mere coincidence is hard to tell. It could lend credence to the theory that the Huns were in fact descendants of the Northern Xiongnu who migrated westward, or that the Huns were using a name borrowed from the Northern Xiongnu, or that these Xiongnu made up part of the Hun confederation.

The Xiongnu-Hun hypothesis originated with the 18th-century French historian Joseph de Guignes, who noticed that ancient Chinese scholars had referred to members of tribes associated with the Xiongnu by names similar to "Hun", albeit with varying Chinese characters. Étienne de la Vaissière has shown that, in the Sogdian script used in the so-called "Sogdian Ancient Letters", both the Xiongnu and Huns were referred to as γwn (xwn), indicating that the two were synonymous.[69] DNA testing of the remains of purported Huns has so far proved inconclusive in determining their origin. Although the theory that the Xiongnu were precursors of the Huns known later in Europe is now accepted by many scholars, it has yet to become a consensus view. The identification with the Huns may be either incorrect or an oversimplification (as would appear to be the case with a proto-Mongol people, the Rouran, who have sometimes been linked to the Avars of Central Europe).

Iranian theories

Harold Walter Bailey proposed an Iranian origin of the Xiongnu, recognizing all the earliest Xiongnu names of the 2nd century BC as being of the Iranian type.[9] This theory is supported by turkologist Henryk Jankowski.[10] Central Asian scholar Christopher I. Beckwith notes that the Xiongnu name could be a cognate of Scythian, Saka and Sogdia, corresponding to a name for Northern Iranians.[27][70] According to Beckwith the Xiongnu could have contained a leading Iranian component when they started out, but more likely they had earlier been subjects of an Iranian people and learned from them the Iranian nomadic model.[27]

In the 1994 UNESCO-published History of Civilizations of Central Asia, its editor János Harmatta claims that the royal tribes and kings of the Xiongnu bore Iranian names, that all Xiongnu words noted by the Chinese can be explained from a Scythian language, and that it is therefore clear that the majority of Xiongnu tribes spoke an Eastern Iranian language.[8]

Mongolic theories

Mongolian and other scholars have suggested that the Xiongnu spoke a language related to the Mongolic languages.[71][72] Mongolian archaeologists proposed that the Slab Grave Culture people were the ancestors of the Xiongnu, and some scholars have suggested that the Xiongnu may have been the ancestors of the Mongols.[11] According to the "Book of Song", the Rourans, whom Book of Wei identified as offspring of Proto-Mongolic[73] Donghu people,[74] possessed the alternative name(s) 大檀 Dàtán "Tatar" and/or 檀檀 Tántán "Tartar" and they were a Xiongnu tribe;[75] Nikita Bichurin considered Xiongnu and Xianbei to be two subgroups (or dynasties) of but one same ethnicity.[76]

Genghis Khan refers to the time of Modu Chanyu as "the remote times of our Chanyu" in his letter to Daoist Qiu Chuji.[77] Sun and moon symbol of Xiongnu that discovered by archaeologists is similar to Mongolian Soyombo symbol.[78][79][80]

Turkic theories

Proponents of a Turkic language theory include E.H. Parker, Jean-Pierre Abel-Rémusat, Julius Klaproth, Kurakichi Shiratori, Gustaf John Ramstedt, Annemarie von Gabain, and Omeljan Pritsak.[13] Some sources say the ruling class was proto-Turkic.[12][81] Craig Benjamin sees the Xiongnu as either proto-Turks or proto-Mongols who possibly spoke a language related to the Dingling.[82]

Chinese sources link the Tiele people and Ashina to the Xiongnu, According to the Book of Zhou and the History of the Northern Dynasties, the Ashina clan was a component of the Xiongnu confederation.[83][84]

Uyghur Khagans claimed descent from the Xiongnu (according to Chinese history Weishu, the founder of the Uyghur Khaganate was descended from a Xiongnu ruler).[85]

Both the 7th-century Chinese History of the Northern Dynasties[86] and the Book of Zhou,[87] an inscription in the Sogdian language, report the Göktürks to be a subgroup of the Xiongnu.[88][89]

Yeniseian theories

Lajos Ligeti was the first to suggest that the Xiongnu spoke a Yeniseian language. In the early 1960s Edwin Pulleyblank was the first to expand upon this idea with credible evidence. In 2000, Alexander Vovin reanalyzed Pulleyblank's argument and found further support for it by utilizing the most recent reconstruction of Old Chinese phonology by Starostin and Baxter and a single Chinese transcription of a sentence in the language of the Jie people, a member tribe of the Xiongnu Confederacy. Previous Turkic interpretations of the aforementioned sentence do not match the Chinese translation as precisely as using Yeniseian grammar.[90] Pulleybank and D. N. Keightley asserted that the Xiongnu titles "were originally Siberian words but were later borrowed by the Turkic and Mongolic peoples".[91] The Xiongnu language gave to the later Turkic and Mongolian empires a number of important culture words including Turkish tängri, Mongolian tenggeri, was originally the Xiongnu word for "heaven", chengli (tháːŋ-wrə́j). Titles such as tarqan, tegin and kaghan were also inherited from the Xiongnu language and probably of Yeniseian origin.[92]

According to Vovin (2007) the Xiongnu likely spoke a Yeniseian language. They were possibly a southern Yeniseian branch.[93]

Multiple ethnicities

Since the early 19th century, a number of Western scholars have proposed a connection between various language families or subfamilies and the language or languages of the Xiongnu. Albert Terrien de Lacouperie considered them to be multi-component groups.[18] Many scholars believe the Xiongnu confederation was a mixture of different ethno-linguistic groups, and that their main language (as represented in the Chinese sources) and its relationships have not yet been satisfactorily determined.[94] Kim rejects "old racial theories or even ethnic affiliations" in favour of the "historical reality of these extensive, multiethnic, polyglot steppe empires".[95]

Chinese sources link the Tiele people and Ashina to the Xiongnu, not all Turkic peoples. According to the Book of Zhou and the History of the Northern Dynasties, the Ashina clan was a component of the Xiongnu confederation,[83][84] but this connection is disputed,[96] and according to the Book of Sui and the Tongdian, they were "mixed nomads" (traditional Chinese: 雜胡; simplified Chinese: 杂胡; pinyin: zá hú) from Pingliang.[97][98] The Ashina and Tiele may have been separate ethnic groups who mixed with the Xiongnu.[99] Indeed, Chinese sources link many nomadic peoples (hu; see Wu Hu) on their northern borders to the Xiongnu, just as Greco-Roman historiographers called Avars and Huns "Scythians". The Greek cognate of Tourkia (Greek: Τουρκία) was used by the Byzantine emperor and scholar Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus in his book De Administrando Imperio,[100][101] though in his use, "Turks" always referred to Magyars.[102] Such archaizing was a common literary topos, and implied similar geographic origins and nomadic lifestyle but not direct filiation.[103]

Some Uyghurs claimed descent from the Xiongnu (according to Chinese history Weishu, the founder of the Uyghur Khaganate was descended from a Xiongnu ruler),[104] but many contemporary scholars do not consider the modern Uyghurs to be of direct linear descent from the old Uyghur Khaganate because modern Uyghur language and Old Uyghur languages are different.[105] Rather, they consider them to be descendants of a number of people, one of them the ancient Uyghurs.[106][107][108]

Language isolate theories

The Turkologist Gerhard Doerfer has denied any possibility of a relationship between the Xiongnu language and any other known language. He also strongly rejected any connection with Turkic or Mongolian.[109]

Geographic origins

The original geographic location of the Xiongnu is disputed among steppe archaeologists. Since the 1960s, the geographic origin of the Xiongnu has attempted to be traced through an analysis of Early Iron Age burial constructions. No region has been proven to have mortuary practices that clearly match those of the Xiongnu.[111]

Archaeology

In the 1920s, Pyotr Kozlov's excavations of the royal tombs at the Noin-Ula burial site in northern Mongolia that date to around the first century CE provided a glimpse into the lost world of the Xiongnu. Other archaeological sites have been unearthed in Inner Mongolia. Those include the Ordos culture of Inner Mongolia, which has been identified as a Xiongnu culture. Sinologist Otto Maenchen-Helfen has said that depictions of the Xiongnu of Transbaikalia and the Ordos show individuals with "Europoid" features.[112] Iaroslav Lebedynsky said that Europoid depictions in the Ordos region should be attributed to a "Scythian affinity".[113]

Portraits found in the Noin-Ula excavations demonstrate other cultural evidences and influences, showing that Chinese and Xiongnu art have influenced each other mutually. Some of these embroidered portraits in the Noin-Ula kurgans also depict the Xiongnu with long braided hair with wide ribbons, which is seen to be identical with the Ashina clan hair-style.[114] Well-preserved bodies in Xiongnu and pre-Xiongnu tombs in the Mongolian Republic and southern Siberia show both Mongoloid and Caucasian features.[115]

Analysis of skeletal remains from some sites attributed to the Xiongnu provides an identification of dolichocephalic Mongoloid, ethnically distinct from neighboring populations in present-day Mongolia.[116] Russian and Chinese anthropological and craniofacial studies show that the Xiongnu were physically very heterogenous, with six different population clusters showing different degrees of Mongoloid and Caucasoid physical traits.[11]

Presently, there exist four fully excavated and well documented cemeteries: Ivolga,[117] Dyrestui,[118] Burkhan Tolgoi,[119][120] and Daodunzi.[121][122] Additionally thousands of tombs have been recorded in Transbaikalia and Mongolia. The Tamir 1 excavation site from a 2005 Silkroad Arkanghai Excavation Project is the only Xiongnu cemetery in Mongolia to be fully mapped in scale.[123] Tamir 1 was located on Tamiryn Ulaan Khoshuu, a prominent granitic outcrop near other cemeteries of the Neolithic, Bronze Age, and Mongol periods.[124] Important finds at the site included a lacquer bowl, glass beads, and three TLV mirrors. Archaeologists from this project believe that these artifacts paired with the general richness and size of the graves suggests that this cemetery was for more important or wealthy Xiongnu individuals.[124]

The TLV mirrors are of particular interest. Three mirrors were acquired from three different graves at the site. The mirror found at feature 160 is believed to be a low-quality, local imitation of a Han mirror, while the whole mirror found at feature 100 and fragments of a mirror found at feature 109 are believed to belong to the classical TLV mirrors and date back to the Xin Dynasty or the early to middle Eastern Han period.[125] The archaeologists have chosen to, for the most part, refrain from positing anything about Han-Xiongnu relations based on these particular mirrors. However, they were willing to mention the following:

"There is no clear indication of the ethnicity of this tomb occupant, but in a similar brick-chambered tomb of the late Eastern Han period at the same cemetery, archaeologists discovered a bronze seal with the official title that the Han government bestowed upon the leader of the Xiongnu. The excavators suggested that these brick chamber tombs all belong to the Xiongnu (Qinghai 1993)."[125]

Classifications of these burial sites make distinction between two prevailing type of burials: "(1) monumental ramped terrace tombs which are often flanked by smaller "satellite" burials and (2) 'circular' or 'ring' burials."[126] Some scholars consider this a division between "elite" graves and "commoner" graves. Other scholars, find this division too simplistic and not evocative of a true distinction because it shows "ignorance of the nature of the mortuary investments and typically luxuriant burial assemblages [and does not account for] the discovery of other lesser interments that do not qualify as either of these types."[127]

Culture

Artistic distinctions

Within the Xiongnu culture more variety is visible from site to site than from "era" to "era," in terms of the Chinese chronology, yet all form a whole that is distinct from that of the Han and other peoples of the non-Chinese north.[128] In some instances iconography can not be used as the main cultural identifier because art depicting animal predation is common among the steppe peoples. An example of animal predation associated with Xiongnu culture is a tiger carrying dead prey.[128] We see a similar image in work from Maoqinggou, a site which is presumed to have been under Xiongnu political control but is still clearly non-Xiongnu. From Maoqinggou, we see the prey replaced by an extension of the tiger's foot. The work also depicts a lower level of execution; Maoqinggou work was executed in a rounder, less detailed style.[128] In its broadest sense, Xiongnu iconography of animal predation include examples such as the gold headdress from Aluchaideng and gold earrings with a turquoise and jade inlay discovered in Xigouban, Inner Mongolia.[128] The gold headdress can be viewed, along with some other examples of Xiongnu art, from the external links at the bottom of this article.

Xiongnu art is harder to distinguish from Saka or Scythian art. There was a similarity present in stylistic execution, but Xiongnu art and Saka art did often differ in terms of iconography. Saka art does not appear to have included predation scenes, especially with dead prey, or same-animal combat. Additionally, Saka art included elements not common to Xiongnu iconography, such as a winged, horned horse.[128] The two cultures also used two different bird heads. Xiongnu depictions of birds have a tendency to have a moderate eye and beak and have ears, while Saka birds have a pronounced eye and beak and no ears.[128]:102–103 Some scholars claim these differences are indicative of cultural differences. Scholar Sophia-Karin Psarras claims that Xiongnu images of animal predation, specifically tiger plus prey, is spiritual, representative of death and rebirth, and same-animal combat is representative of the acquisition of or maintenance of power.[128]:102–103

Rock art and writing

The rock art of the Yin and Helan Mountains is dated from the 9th millennium BC to the 19th century AD. It consists mainly of engraved signs (petroglyphs) and only minimally of painted images.[129]

Excavations conducted between 1924 and 1925 in the Noin-Ula kurgans produced objects with over twenty carved characters, which were either identical or very similar to that of to the runic letters of the Old Turkic alphabet discovered in the Orkhon Valley. From this a some scholars hold that the Xiongnu had a script similar to Eurasian runiform and this alphabet itself served as the basis for the ancient Turkic writing.[130]

The Records of the Grand Historian (vol. 110) state that when the Xiongnu noted down something or transmitted a message, they made cuts on a piece of wood; they also mention a "Hu script".

2nd century BCE – 2nd century CE characters of Hun-Xianbei script (Mongolia and Inner Mongolia), N. Ishjamts, "Nomads In Eastern Central Asia", in the History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume 2, Fig 5, p. 166, UNESCO Publishing, 1996, ISBN 92-3-102846-4

2nd century BCE – 2nd century CE characters of Hun-Xianbei script (Mongolia and Inner Mongolia), N. Ishjamts, "Nomads In Eastern Central Asia", in the History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume 2, Fig 5, p. 166, UNESCO Publishing, 1996, ISBN 92-3-102846-4 2nd century BCE – 2nd century CE, characters of Hun-Xianbei script (Mongolia and Inner Mongolia), N. Ishjamts, "Nomads In Eastern Central Asia", in the History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume 2, Fig 5, p. 166, UNESCO Publishing, 1996, ISBN 92-3-102846-4

2nd century BCE – 2nd century CE, characters of Hun-Xianbei script (Mongolia and Inner Mongolia), N. Ishjamts, "Nomads In Eastern Central Asia", in the History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume 2, Fig 5, p. 166, UNESCO Publishing, 1996, ISBN 92-3-102846-4

Diet

Xiongnu were a nomadic people. From their lifestyle of herding flocks and their horse-trade with China, it can be concluded that their diet consist mainly of mutton, horse meat and wild geese that were shot down.

Possible connection to Korean Silla Dynasty

In various kinds of ancient inscriptions on monuments of Munmu of Silla, it is recorded that King Munmu possibly came from an unknown Xiongnu-tribe or that he has partially Xiongnu ancestry. According to several historians, it is possible that this unknown tribe was originally of Koreanic origin and joined the Xiongnu confederation. Later the tribes ruling family returned to Korea and married into the royal family of Silla. There are also some Korean researchers that point out that the grave goods of Silla and of the eastern Xiongnu are alike.[131][132][133][134][135]

See also

- List of Xiongnu rulers (Chanyus)

- Rulers family tree

- Nomadic empire

- Ethnic groups in Chinese history

- History of the Han Dynasty

- Ban Yong

- Zubu

- List of largest empires

References

Citations

- Zheng Zhang (Chinese: 鄭張), Shang-fang (Chinese: 尚芳). 匈 – 字 – 上古音系 – 韻典網. ytenx.org [韻典網]. Rearranged by BYVoid.

- Zheng Zhang (Chinese: 鄭張), Shang-fang (Chinese: 尚芳). 奴 – 字 – 上古音系 – 韻典網. ytenx.org [韻典網]. Rearranged by BYVoid.

- "Xiongnu People". britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- di Cosmo 2004: 186

- Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 19, 26–27. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

- Beckwith 2009, pp. 51–52, 404–405

- Vaissière 2006

- Harmatta 1994, p. 488: "Their royal tribes and kings (shan-yü) bore Iranian names and all the Hsiung-nu words noted by the Chinese can be explained from an Iranian language of Saka type. It is therefore clear that the majority of Hsiung-nu tribes spoke an Eastern Iranian language."

- Bailey 1985, pp. 21–45

- Jankowski 2006, pp. 26–27

- Tumen D., "Anthropology of Archaeological Populations from Northeast Asia Archived 2013-07-29 at the Wayback Machine page 25, 27

- Hucker 1975: 136

- Pritsak 1959

- Di Cosmo, 2004, pg 166

- Adas 2001: 88

- Vovin, Alexander. "Did the Xiongnu speak a Yeniseian language?". Central Asiatic Journal 44/1 (2000), pp. 87–104.

- 高晶一, Jingyi Gao (2017). 確定夏國及凱特人的語言為屬於漢語族和葉尼塞語系共同詞源 [Xia and Ket Identified by Sinitic and Yeniseian Shared Etymologies]. Central Asiatic Journal. 60 (1–2): 51–58. doi:10.13173/centasiaj.60.1-2.0051. JSTOR 10.13173/centasiaj.60.1-2.0051.

- Geng 2005

- "The Account of the Xiongnu,Records of the Grand Historian",Sima Qian.DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004216358_00

- Di Cosmo 2002, 2.

- Di Cosmo 2002, 129.

- Di Cosmo 2002, 107.

- Di Cosmo 1999, 892–893.

- Pulleyblank 2000, p. 20.

- Di Cosmo 1999, 892–893 & 964.

- Rawson, Jessica (2017). "China and the steppe: reception and resistance". Antiquity. 91 (356): 375–388. doi:10.15184/aqy.2016.276. ISSN 0003-598X.

- Beckwith 2009, pp. 71–73

- Bentley, Jerry H., Old World Encounters, 1993, pg. 38

- Barfield 1989

- di Cosmo 1999: 885–966

- Jerry Bentley, Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 36.

- 又《漢書》:"使王烏等窺匈奴。法,漢使不去節,不以墨黥面,不得入穹盧。王烏等去節、黥面,得入穹盧,單於愛之。" from Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang, Scroll 8 Translation from Reed, Carrie E. (2000). "Tattoo in Early China". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 120 (3): 360–376. doi:10.2307/606008. JSTOR 606008.

- Yü, Ying-shih (1986). "Han Foreign Relations". The Cambridge History of China, Volume 1: The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BC – AD 220. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 384. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- Barfield, Thomas J. (1981). "The Hsiung-nu imperial confederacy: Organization and foreign policy". The Journal of Asian Studies. 41 (1): 45–61. doi:10.2307/2055601. JSTOR 2055601.

- Grousset 1970

- Yap, page liii

- Grousset, page 20

- , p. 31.

- Qian Sima; Burton Watson (January 1993). Records of the Grand Historian: Han dynasty. Renditions-Columbia University Press. pp. 161–. ISBN 978-0-231-08166-5.

- Monumenta Serica. H. Vetch. 2004. p. 81.

- Frederic E. Wakeman (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 41–. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- Lin Jianming (林剑鸣) (1992). 秦漢史 [History of Qin and Han]. Wunan Publishing. pp. 557–8. ISBN 978-957-11-0574-1.

- China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200–750 AD. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2004. pp. 18–. ISBN 978-1-58839-126-1.

sima.

- James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian crossroads: a history of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- Julia Lovell (2007). The Great Wall: China Against the World, 1000 BC – AD 2000. Grove Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-8021-4297-9. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- Alfred J. Andrea; James H. Overfield (1998). The Human Record: To 1700. Houghton Mifflin. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-395-87087-7. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- Yiping Zhang (2005). Story of the Silk Road. China Intercontinental Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-7-5085-0832-0. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- Charles Higham (2004). Encyclopedia of ancient Asian civilizations. Infobase Publishing. p. 409. ISBN 978-0-8160-4640-9. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- Indian Society for Prehistoric & Quaternary Studies (1998). Man and environment, Volume 23, Issue 1. Indian Society for Prehistoric and Quaternary Studies. p. 6. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- Adrienne Mayor (22 September 2014). The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World. Princeton University Press. pp. 422–. ISBN 978-1-4008-6513-0.

- Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

- Loewe 1974.

- Han Shu (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju ed) 94B, p. 3824.

- Bentley, Jerry H, "Old World Encounters", 1993, p. 37

- Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 42–47. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

- Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

- Fairbank & Têng 1941.

- Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

- Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

- Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

- Fang, Xuanling (1958). 晉書 [Book of Jin] (in Chinese). Beijing: Commercial Press. Vol. 97

- Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

- Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

- Sand-covered Hun City Unearthed, CN: China

- National Geographic (online ed.)

- Obrusánszky 2006.

- Barfield, Thomas J (1989), The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China, 221 BC to AD 1757

- Baxter-Sagart (2014).

- Vaissière, Étienne. "Xiongnu". Encyclopedia Iranica. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Beckwith 2009, p. 405: "Accordingly, the transcription now read as Hsiung- nu may have been pronounced * Soγdâ, * Soγlâ, * Sak(a)dâ, or even * Skla(C)da, etc."

- Ts. Baasansuren "The scholar who showed the true Mongolia to the world", Summer 2010 vol.6 (14) Mongolica, pp.40

- Denis, Sinor. Aspects of Altaic Civilization III.

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (2000). "Ji 姬 and Jiang 姜: The Role of Exogamic Clans in the Organization of the Zhou Polity", Early China. p. 20

- Wei Shou. Book of Wei. vol. 91 "蠕蠕,東胡之苗裔也,姓郁久閭氏" tr. "Rúrú, offsprings of Dōnghú, surnamed Yùjiŭlǘ"

- Golden, Peter B. "Some Notes on the Avars and Rouran", in The Steppe Lands and the World beyond Them. Ed. Curta, Maleon. Iași (2013). pp. 54-55

- N.Bichurin "Collection of information on the peoples who inhabited Central Asia in ancient times", 1950, p. 227

- Howorth, Henry H. (Henry Hoyle). History of the Mongols from the 9th to the 19th century. London : Longmans, Green – via Internet Archive.

- "Sun and Moon" (JPG). depts.washington.edu.

- "Xiongnu Archaeology". depts.washington.edu.

- Elite Xiongnu Burials at the Periphery (Miller et al. 2009)

- Wink 2002: 60–61

- Craig Benjamin (2007, 49), In: Hyun Jin Kim, The Huns, Rome and the Birth of Europe. Cambridge University Press. 2013. page 176.

- Linghu Defen et al., Book of Zhou, Vol. 50. (in Chinese)

- Li Yanshou (李延寿), History of the Northern Dynasties, Vol. 99. (in Chinese)

- Peter B. Golden (1992). "Chapter VI – The Uyğur Qağante (742–840)". An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples: Ethnogenesis and State-Formation in Medieval and Early Modern Eurasia and the Middle East. p. 155. ISBN 978-3-447-03274-2.

- History of Northern Dynasties, vol. 99

- Book of Zhou, vol. 50

- Henning 1948

- Sims-Williams 2004

- Vovin 2000

- Nicola Di Cosmo (2004). Cambridge. page 164

- THE PEOPLES OF THE STEPPE FRONTIER IN EARLY CHINESE SOURCES, Edwin G. Pulleyblank, page 49

- "ONCE AGAIN ON THE ETYMOLOGY OF THE TITLE qaγan" Alexander VOVIN (Honolulu) – Studia Etymologica Cracoviensia vol. 12 Kraków 2007 (http://ejournals.eu/sj/index.php/SEC/article/viewFile/1100/1096)

- Di Cosmo 2004: 165

- Hyun Jin Kim, The Huns, Rome and the Birth of Europe. ISBN 978-1-107-00906-6. Cambridge University Press. 2013. page 31.

- Christian, p. 249

- Wei Zheng et al., Book of Sui, Vol. 84. (in Chinese)

- Du, You (1988). 辺防13 北狄4 突厥上. 《通典》 [Tongdian] (in Chinese). 197. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. p. 5401. ISBN 978-7-101-00258-4.

- "Об эт нической принадлежности Хунну". rudocs.exdat.com.

- Jenkins, Romilly James Heald (1967). De Administrando Imperio by Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus. Corpus fontium historiae Byzantinae (New, revised ed.). Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-88402-021-9. Retrieved 28 August 2013. According to Constantine Porphyrogenitus, writing in his De Administrando Imperio (ca. 950 AD) "Patzinakia, the Pecheneg realm, stretches west as far as the Siret River (or even the Eastern Carpathian Mountains), and is four days distant from Tourkia (i.e. Hungary)."

- Günter Prinzing; Maciej Salamon (1999). Byzanz und Ostmitteleuropa 950–1453: Beiträge zu einer table-ronde des XIX. International Congress of Byzantine Studies, Copenhagen 1996. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 46. ISBN 978-3-447-04146-1. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- Henry Hoyle Howorth (2008). History of the Mongols from the 9th to the 19th Century: The So-called Tartars of Russia and Central Asia. Cosimo, Inc. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-60520-134-4. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- Sinor (1990)

- Peter B. Golden (1992). "Chapter VI – The Uyğur Qağante (742–840)". An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples: Ethnogenesis and State-Formation in Medieval and Early Modern Eurasia and the Middle East. p. 155. ISBN 978-3-447-03274-2.

- Nabijan Tursun. "The Formation of Modern Uyghur Historiography and Competing Perspectives toward Uyghur History". The China and Eurasia Forum Quarterly. 6 (3): 87–100.

- James A. Millward & Peter C. Perdue (2004). "Chapter 2: Political and Cultural History of the Xinjiang Region through the Late Nineteenth Century". In S. Frederick Starr (ed.). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland. M. E. Sharpe. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-0-7656-1318-9.

- Susan J. Henders (2006). Susan J. Henders (ed.). Democratization and Identity: Regimes and Ethnicity in East and Southeast Asia. Lexington Books. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-7391-0767-6. Retrieved 2011-09-09.

- Reed, J. Todd; Raschke, Diana (2010). The ETIM: China's Islamic Militants and the Global Terrorist Threat. ABC-CLIO. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-313-36540-9.

- Di Cosmo 2004: 164

- Helfen-Maenchen,-Helfen, Otto (1973). The World of the Huns: Studies of Their History and Culture, pp.371. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 371.

- Honeychurch, William. "Thinking Political Communities: The State and Social Stratification among Ancient Nomads of Mongolia". The Anthropological Study of Class and Consciousness: 47.

- Maenchen-Helfen, Otto (1 August 1973). The World of the Huns (1 ed.). UC Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 370–371. ISBN 0520015967.

- Lebedynsky 2007, p. 125 "Europoid faces in some depictions of the Ordos, which should be attributed to a Scythian affinity"

- Camilla Trever, "Excavations in Northern Mongolia (1924–1925)", Leningrad: J. Fedorov Printing House, 1932

- The Great Empires of the Ancient World – Thomas Harrison – 2009 – page 288

- Fu ren da xue (Beijing, China), S.V.D. Research Institute, Society of the Divine Word – 2003

- A. V. Davydova, Ivolginskii arkheologicheskii kompleks II. Ivolginskii mogil'nik. Arkheologicheskie pamiatniki Siunnu 2 (Sankt-Peterburg 1996). А. В. Давыдова, Иволгинский археологи-ческий комплекс II. Иволгинский могильник. Археологические памятники Сюнну 2 (Санкт-Петербург 1996).

- S. S. Miniaev, Dyrestuiskii mogil'nik. Arkheologicheskie pamiatniki Siunnu 3 (Sankt-Peterburg 1998). С. С. Миняев, Дырестуйский могильник. Археологические памятники Сюнну 3 (Санкт-Петербург 1998).

- Ts. Törbat, Keramika khunnskogo mogil'nika Burkhan-Tolgoi. Erdem shinzhilgeenii bichig. Arkheologi, antropologi, ugsaatan sudlal 19,2003, 82–100. Ц. Тѳрбат, Керамика хуннского могильника Бурхан-Толгой. Эрдэм шинжилгээний бичиг. Археологи, антропологи, угсаатан судлал 19, 2003, 82–100.

- Ts. Törbat, Tamiryn Ulaan khoshuuny bulsh ba Khünnügiin ugsaatny büreldekhüünii asuudald. Tükhiin setgüül 4, 2003, 6–17. Ц. Төрбат, Тамирын Улаан хошууны булш ба Хүннүгийн угсаатны бүрэлдэхүүний асуудалд. Түүхийн сэтгүүл 4, 2003, 6–17.

- Ningxia Cultural Relics and Archaeology Research Institute (寧夏文物考古研究所); Chinese Academy of Social Sciences Archaeology Institute Ningxia Archaeology Group; Tongxin County Cultural Relics Administration (同心縣文物管理所) (1988). 寧夏同心倒墩子匈奴墓地. 考古學報 [Archaeology Journal] (3): 333–356.

- Miller, Bryan (2011). Jan Bemmann (ed.). Xiongnu Archaeology. Bonn: Vor- und Fruhgeschichtliche Archaeologie Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universitat Bonn. ISBN 978-3-936490-14-5.

- Purcell, David. "Maps of the Xiongnu Cemetery at Tamiryn Ulaan Khoshuu, Ogii nuur, Arkhangai Aimag, Mongolia" (PDF). The Silk Road. 9: 143–145.

- Purcell, David; Kimberly Spurr. "Archaeological Investigations of Xiongnu Sites in the Tamir River Valley" (PDF). The Silk Road. 4 (1): 20–31.

- Lai, Guolong. "The Date of the TLV Mirrors from the Xiongnu Tombs" (PDF). The Silk Road. 4 (1): 34–43.

- Miller, Bryan (2011). Jan Bemmann (ed.). Xiongnu Archaeology. Bonn: Vor- und Fruhgeschichtliche Archaologie Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universitat Bonn. p. 23. ISBN 978-3-936490-14-5.

- Miller, Bryan (2011). Jan Bemmann (ed.). Xiongnu Archaeology. Bonn: Vor- und Fruhgeschichtliche Archaologie Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universitat Bonn. p. 24. ISBN 978-3-936490-14-5.

- Psarras, Sophia-Karin (2003). "Han and Xiongnu: A Reexamination of Cultural and Political Relations". Monumenta Serica. 51: 55–236. doi:10.1080/02549948.2003.11731391. JSTOR 40727370.

- Demattè 2006

- Ishjamts 1996: 166

- Cho Gab-je. 騎馬흉노국가 新羅 연구 趙甲濟(月刊朝鮮 편집장)의 심층취재 내 몸속을 흐르는 흉노의 피 (in Korean). Monthly Chosun. Retrieved 2016-09-25.

- 김운회 (2005-08-30). 김운회의 '대쥬신을 찾아서' <23> 금관의 나라, 신라" (in Korean). 프레시안. Retrieved 2016-09-25.

- 경주 사천왕사(寺) 사천왕상(四天王像) 왜 4개가 아니라 3개일까 (in Korean). 조선일보. 2009-02-27. Archived from the original on 2014-12-30. Retrieved 2016-09-25.

- 김창호, 〈문무왕릉비에 보이는 신라인의 조상인식 – 태조성한의 첨보 -〉, 《한국사연구》, 한국사연구회, 1986년

- "자료검색>상세_기사 | 국립중앙도서관". www.nl.go.kr. Archived from the original on 2018-10-02. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

Sources

- Primary sources

- Ban Gu et al., Book of Han, esp. vol. 94, part 1, part 2.

- Fan Ye et al., Book of the Later Han, esp. vol. 89.

- Sima Qian et al., Records of the Grand Historian, esp. vol. 110.

- Other sources consulted

- Adas, Michael. 2001. Agricultural and Pastoral Societies in Ancient and Classical History, American Historical Association/Temple University Press.

- Bailey, Harold W. (1985). Indo-Scythian Studies: being Khotanese Texts, VII. Cambridge University Press. JSTOR 312539. Retrieved 30 May 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barfield, Thomas. 1989. The Perilous Frontier. Basil Blackwell.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (16 March 2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13589-2. Retrieved 30 May 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brosseder, Ursula, and Bryan Miller. Xiongnu Archaeology: Multidisciplinary Perspectives of the First Steppe Empire in Inner Asia. Bonn: Freiburger Graphische Betriebe- Freiburg, 2011.

- Csányi, B. et al. 2008. Y-Chromosome Analysis of Ancient Hungarian and Two Modern Hungarian-Speaking Populations from the Carpathian Basin. Annals of Human Genetics, 2008 March 27, 72(4): 519–534.

- Demattè, Paola. 2006. Writing the Landscape: Petroglyphs of Inner Mongolia and Ningxia Province (China). In: Beyond the steppe and the sown: proceedings of the 2002 University of Chicago Conference on Eurasian Archaeology, edited by David L. Peterson et al. Brill. Colloquia Pontica: series on the archaeology and ancient history of the Black Sea area; 13. 300–313. (Proceedings of the First International Conference of Eurasian Archaeology, University of Chicago, May 3–4, 2002.)

- Davydova, Anthonina. The Ivolga archaeological complex. Part 1. The Ivolga fortress. In: Archaeological sites of the Xiongnu, vol. 1. St Petersburg, 1995.

- Davydova, Anthonina. The Ivolga archaeological complex. Part 2. The Ivolga cemetery. In: Archaeological sites of the Xiongnu, vol. 2. St Petersburg, 1996.

- (in Russian) Davydova, Anthonina & Minyaev Sergey. The complex of archaeological sites near Dureny village. In: Archaeological sites of the Xiongnu, vol. 5. St Petersburg, 2003.

- Davydova, Anthonina & Minyaev Sergey. The Xiongnu Decorative bronzes. In: Archaeological sites of the Xiongnu, vol. 6. St Petersburg, 2003.

- Di Cosmo, Nicola. 1999. The Northern Frontier in Pre-Imperial China. In: The Cambridge History of Ancient China, edited by Michael Loewe and Edward Shaughnessy. Cambridge University Press.

- Di Cosmo, Nicola. 2004. Ancient China and its Enemies: The Rise of Nomadic Power in East Asian History. Cambridge University Press. (First paperback edition; original edition 2002)

- J.K., Fairbank; Têng, S.Y. (1941). "On the Ch'ing Tributary System". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 6 (2): 135–246. doi:10.2307/2718006. JSTOR 2718006.

- Geng, Shimin [耿世民] (2005). 阿尔泰共同语、匈奴语探讨 [On Altaic Common Language and Xiongnu Language]. Yu Yan Yu Fan Yi 语言与翻译(汉文版) [Language and Translation] (2). ISSN 1001-0823. OCLC 123501525. Archived from the original on 25 February 2012.

- Genome News Network. 2003 July 25. "Ancient DNA Tells Tales from the Grave"

- Grousset, René. 1970. The empire of the steppes: a history of central Asia. Rutgers University Press.

- (in Russian) Gumilev L. N. 1961. История народа Хунну (History of the Hunnu people).

- Hall, Mark & Minyaev, Sergey. Chemical Analyses of Xiong-nu Pottery: A Preliminary Study of Exchange and Trade on the Inner Asian Steppes. In: Journal of Archaeological Science (2002) 29, pp. 135–144

- Harmatta, János (1 January 1994). "Conclusion". In Harmatta, János (ed.). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The Development of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilizations, 700 B. C. to A. D. 250. UNESCO. pp. 485–492. ISBN 978-9231028465. Retrieved 29 May 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- (in Hungarian) Helimski, Eugen. "A szamojéd népek vázlatos története" (Short History of the Samoyedic peoples). In: The History of the Finno-Ugric and Samoyedic Peoples. 2000, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary.

- Henning W. B. 1948. The date of the Sogdian ancient letters. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies (BSOAS), 12(3–4): 601–615.

- Hill, John E. (2009) Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd Centuries CE. BookSurge, Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1. (Especially pp. 69–74)

- Hucker, Charles O. 1975. China's Imperial Past: An Introduction to Chinese History and Culture. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2353-2

- N. Ishjamts. 1999. Nomads In Eastern Central Asia. In: History of civilizations of Central Asia. Volume 2: The Development of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilizations, 700 bc to ad 250; Edited by Janos Harmatta et al. UNESCO. ISBN 92-3-102846-4. 151–170.

- Jankowski, Henryk (2006). Historical-Etymological Dictionary of Pre-Russian Habitation Names of the Crimea. Handbuch der Orientalistik [HdO], 8: Central Asia; 15. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-15433-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- (in Russian) Kradin N.N., "Hun Empire". Acad. 2nd ed., updated and added., Moscow: Logos, 2002, ISBN 5-94010-124-0

- Kradin, Nikolay. 2005. Social and Economic Structure of the Xiongnu of the Trans-Baikal Region. Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia, No 1 (21), p. 79–86.

- Kradin, Nikolay. 2012. New Approaches and Challenges for the Xiongnu Studies. In: Xiongnu and its eastward Neighbours. Seoul, p. 35–51.

- (in Russian) Kiuner (Kjuner, Küner) [Кюнер], N.V. 1961. Китайские известия о народах Южной Сибири, Центральной Азии и Дальнего Востока (Chinese reports about peoples of Southern Siberia, Central Asia, and Far East). Moscow.

- (in Russian) Klyashtorny S.G. [Кляшторный С.Г.]. 1964. Древнетюркские рунические памятники как источник по истории Средней Азии. (Ancient Türkic runiform monuments as a source for the history of Central Asia). Moscow: Nauka.

- (in German) Liu Mau-tsai. 1958. Die chinesischen Nachrichten zur Geschichte der Ost-Türken (T'u-küe). Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

- Loewe, Michael. 1974. The campaigns of Han Wu-ti. In: Chinese ways in warfare, ed. Frank A. Kierman, Jr., and John K. Fairbank. Harvard Univ. Press.

- Maenschen-Helfen, Otto (1973). The World of the Huns: Studies in Their History and Culture. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-01596-8. Retrieved February 18, 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Minyaev, Sergey. On the origin of the Xiongnu // Bulletin of International association for the study of the culture of Central Asia, UNESCO. Moscow, 1985, No. 9.

- Minyaev, Sergey. News of Xiongnu Archaeology // Das Altertum, vol. 35. Berlin, 1989.

- Miniaev, Sergey. "Niche Grave Burials of the Xiong-nu Period in Central Asia", Information Bulletin, Inter-national Association for the Cultures of Central Asia 17(1990): 91–99.

- Minyaev, Sergey. The excavation of Xiongnu Sites in the Buryatia Republic// Orientations, vol. 26, n. 10, Hong Kong, November 1995.

- Minyaev, Sergey. Les Xiongnu// Dossiers d' archaeologie, # 212. Paris 1996.

- Minyaev, Sergey. Archaeologie des Xiongnu en Russie: nouvelles decouvertes et quelques Problemes. In: Arts Asiatiques, tome 51, Paris, 1996.

- Minyaev, Sergey. The origins of the "Geometric Style" in Hsiungnu art // BAR International series 890. London, 2000.

- Minyaev, Sergey. Art and archeology of the Xiongnu: new discoveries in Russia. In: Circle of Iner Asia Art, Newsletter, Issue 14, December 2001, pp. 3–9

- Minyaev, Sergey & Smolarsky Phillipe. Art of the Steppes. Brussels, Foundation Richard Liu, 2002.

- (in Russian) Minyaev, Sergey. Derestuj cemetery. In: Archaeological sites of the Xiongnu, vol. 3. St-Petersburg, 1998.

- Miniaev, Sergey & Sakharovskaja, Lidya. Investigation of a Xiongnu Royal Tomb in the Tsaraam valley, part 1. In: Newsletters of the Silk Road Foundation, vol. 4, no.1, 2006.

- Miniaev, Sergey & Sakharovskaja, Lidya. Investigation of a Xiongnu Royal Tomb in the Tsaraam valley, part 2. In: Newsletters of the Silk Road Foundation, vol. 5, no.1, 2007.

- (in Russian) Minyaev, Sergey. The Xiongnu cultural complex: location and chronology. In: Ancient and Middle Age History of Eastern Asia. Vladivostok, 2001, pp. 295–305.

- Miniaev, Sergey & Elikhina, Julia. On the chronology of the Noyon Uul barrows. The Silk Road 7 (2009: 21–30).

- (in Hungarian) Obrusánszky, Borbála. 2006 October 10. Huns in China (Hunok Kínában) 3.

- (in Hungarian) Obrusánszky, Borbála. 2009. Tongwancheng, city of the southern Huns. Transoxiana, August 2009, 14. ISSN 1666-7050.

- (in French) Petkovski, Elizabet. 2006. Polymorphismes ponctuels de séquence et identification génétique: étude par spectrométrie de masse MALDI-TOF. Strasbourg: Université Louis Pasteur. Dissertation

- (in Russian) Potapov L.P. [Потапов, Л. П.] 1969. Этнический состав и происхождение алтайцев (Etnicheskii sostav i proiskhozhdenie altaitsev, Ethnic composition and origins of the Altaians). Leningrad: Nauka. Facsimile in Microsoft Word format.

- (in German) Pritsak O. 1959. XUN Der Volksname der Hsiung-nu. Central Asiatic Journal, 5: 27–34.

- Psarras, Sophia-Karin. "HAN AND XIONGNU: A REEXAMINATION OF CULTURAL AND POLITICAL RELATIONS (I)." Monumenta Serica. 51. (2003): 55–236. Web. 12 Dec. 2012. <https://www.jstor.org/stable/40727370>.

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (2000). "Ji 姬 and Jiang 姜: The Role of Exogamic Clans in the Organization of the Zhou Polity" (PDF). Early China. 25 (25): 1–27. doi:10.1017/S0362502800004259. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-11-18. Retrieved 2017-12-01.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sims-Williams, Nicholas. 2004. The Sogdian ancient letters. Letters 1, 2, 3, and 5 translated into English.

- (in Russian) Talko-Gryntsevich, Julian. Paleo-Ethnology of Trans-Baikal area. In: Archaeological sites of the Xiongnu, vol. 4. St Petersburg, 1999.

- Taskin V.S. [Таскин В.С.]. 1984. Материалы по истории древних кочевых народов группы Дунху (Materials on the history of the ancient nomadic peoples of the Dunhu group). Moscow.

- Toh, Hoong Teik (2005). "The -yu Ending in Xiongnu, Xianbei, and Gaoju Onomastica" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. 146.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vaissière (2005). "Huns et Xiongnu". Central Asiatic Journal (in French). 49 (1): 3–26.

- Vaissière, Étienne de la. 2006. Xiongnu. Encyclopædia Iranica online.

- Vovin, Alexander (2000). "Did the Xiongnu speak a Yeniseian language?". Central Asiatic Journal. 44 (1): 87–104.

- Wink, A. 2002. Al-Hind: making of the Indo-Islamic World. Brill. ISBN 0-391-04174-6

- Yap, Joseph P. (2009). "Wars with the Xiongnu: A translation from Zizhi tongjian". AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4490-0604-4

- Zhang, Bibo (张碧波); Dong, Guoyao (董国尧) (2001). 中国古代北方民族文化史 [Cultural History of Ancient Northern Ethnic Groups in China]. Harbin: Heilongjiang People's Press. ISBN 978-7-207-03325-3.

Further reading

| Library resources about Xiongnu |

- (in Russian) Потапов, Л. П. 1966. Этнионим Теле и Алтайцы. Тюркологический сборник, 1966: 233–240. Moscow: Nauka. (Potapov L.P., The ethnonym "Tele" and the Altaians. Turcologica 1966: 233–240).

- Houle, J. and L.G. Broderick 2011 "Settlement Patterns and Domestic Economy of the Xiongnu in Khanui Valley, Mongolia", 137–152. In Xiongnu Archaeology: Multidisciplinary Perspectives of the First Steppe Empire in Inner Asia.

- Yap, Joseph P, (2019). The Western Regions, Xiongnu and Han, from the Shiji, Hanshu and Hou Hanshu. ISBN 978-1792829154

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Xiongnu. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Hiung-nu. |

- Li, Chunxiang; Li, Hongjie; Cui, Yinqiu; Xie, Chengzhi; Cai, Dawei; Li, Wenying; Victor, Mair H.; Xu, Zhi; Zhang, Quanchao; Abuduresule, Idelisi; Jin, Li; Zhu, Hong; Zhou, Hui (2010). "Evidence that a West-East admixed population lived in the Tarim Basin as early as the early Bronze Age". BMC Biology. 8: 15. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-8-15. PMC 2838831. PMID 20163704.

- Material Culture presented by University of Washington

- Encyclopedic Archive on Xiongnu

- The Xiongnu Empire

- The Silk Road Volume 4 Number 1

- The Silk Road Volume 9

- Gold Headdress from Aluchaideng

- Belt buckle, Xiongnu type, 3rd–2nd century B.C.

- Videodocumentation: Xiongnu – the burial site of the Hun prince (Mongolia)

- The National Museum of Mongolian History :: Xiongnu

.png)