Ganzhou Uyghur Kingdom

The Ganzhou Uyghur Kingdom (traditional Chinese: 甘州回鶻; simplified Chinese: 甘州回鹘; pinyin: Gānzhōu Huíhú), also referred to as the Hexi Uyghurs, was established in 894 around Gan Prefecture in modern Zhangye.[1][2] The kingdom lasted from 894 to 1036; during that time, many of Ganzhou's residents converted to Buddhism.[3]

Ganzhou Uyghur Kingdom | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 894–1036 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Status | Kingdom | ||||||||

| Capital | Gan Prefecture (Zhangye) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Old Uyghur language Middle Chinese | ||||||||

| Religion | Manichaeism Buddhism | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Idiqut | |||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 894 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1036 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | China | ||||||||

| History of the Turkic peoples pre-14th century |

|---|

History of the Turkic peoples |

| Göktürks |

|

| Khazar Khaganate 618–1048 |

| Xueyantuo 628–646 |

| Kangar union 659–750 |

| Turk Shahi 665-850 |

| Türgesh Khaganate 699–766 |

| Kimek confederation 743–1035 |

| Uyghur Khaganate 744–840 |

| Oghuz Yabgu State 750–1055 |

| Karluk Yabgu State 756–940 |

| Kara-Khanid Khanate 840–1212 |

| Ganzhou Uyghur Kingdom 848–1036 |

| Qocho 856–1335 |

| Pecheneg Khanates 860–1091 |

| Ghaznavid Empire 963–1186 |

| Seljuk Empire 1037–1194 |

| Cumania 1067–1239 |

| Khwarazmian Empire 1077–1231 |

| Kerait Khanate 11th century–13th century |

| Delhi Sultanate 1206–1526 |

| Qarlughid Kingdom 1224–1266 |

| Golden Horde 1240s–1502 |

| Mamluk Sultanate (Cairo) 1250–1517 |

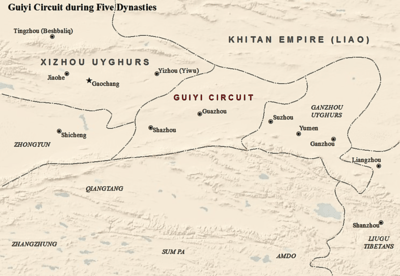

The Hexi Corridor, located within modern Gansu, was traditionally a Chinese inroad into Central Asia. From the 9th to 11th centuries this area was shared between the Ganzhou Uyghurs and the Guiyi Circuit. By the early 11th century both the Uyghurs and Guiyi Circuit were conquered by the Tangut people of the Western Xia dynasty.[4]

The Ganzhou Uyghur rulers were descended from the House of Yaglakar.

History

There was a pre-existing community of Uyghurs at Gan Prefecture by 840 at the very latest.

Around the years 881 and 882, Gan Prefecture slipped from the control of the Guiyi Circuit.

In 894 the Uyghurs established the Ganzhou Uyghur Kingdom in Gan Prefecture.

In 910 the Ganzhou Uyghurs attacked the Kingdom of Jinshan (Guiyi).

In 911 the Ganzhou Uyghurs attacked the Kingdom of Jinshan and forced them into an alliance as a lesser partner.

In 916 a Ganzhou Uyghur princess was married to Cao Yijin, governor of the Guiyi Circuit.

In 920 Huaijian Khagan became sickly.

In 924 Huaijian Khagan died and his sons Diyin and Renmei fought over the throne with Diyin coming out on top.

In 925 Cao Yijin led an attack on the Ganzhou Uyghurs and defeated them.

In 926 Diyin died and Aduoyu succeeded him as Shunhua Khagan. Shunhua Khagan married Cao Yijin's daughter.

In 930 Cao Yijin visited the Ganzhou Uyghur court in Gan Prefecture.

In 933 Shunhua Khagan died and Jingqiong succeeded him.

In 961 the Ganzhou Uyghurs accepted the Song dynasty as suzerains.[5]

In 975 Jingqiong died and Yeluohe Mili'e succeeded him.

In 983 Jingqiong died and Lusheng succeeded him.

In 1003 Lusheng died and Zhongshun Baode Khagan succeeded him. The Tanguts attacked the Ganzhou Uyghurs but were defeated.

In 1008 the Ganzhou Uyghurs and Tanguts engaged in combat and the Uyghurs emerged victorious. The Liao dynasty attacked the Ganzhou Uyghurs and defeated them.

In 1009 the Ganzhou Uyghurs captured Liang Prefecture.

In 1010 the Liao dynasty attacked the Ganzhou Uyghurs and defeated them.

In 1016 Zhongshun Baode Khagan died and Huaining Shunhua Khagan succeeded him.

In 1023 Huaining Shunhua Khagan died and Guizhong Baoshun Khagan succeeded him.

In 1026 the Ganzhou Uyghurs were defeated in battle by the Liao dynasty.

In 1028 the Ganhzhou Uyghurs were defeated by the Tanguts. Guizhong Baoshun Khagan died and Baoguo Khagan succeeded him.

In 1036 the Ganzhou Uyghur Kingdom was annexed by the Tanguts. After the destruction of their realm, the Ganzhou Uyghurs migrated west and settled between Dunhuang and the Qaidam Basin, where they came be known as the Yellow Head Uyghurs. They practiced Buddhism and lived as pastoral nomads. Their descendants are today known as the Yugurs.

See also

References

- Golden 2011, p. 47.

- Millward 2007, p. 46.

- Bosworth 2000, p. 70.

- Bell, Connor Joseph (2008). The Uyghur Transformation in Medieval Inner Asia: From Nomadic Turkic Tradition to Cultured Mongol Administrators. ProQuest. pp. 65–69. ISBN 9780549807957. Retrieved 21 December. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - http://www.chinaknowledge.de/History/Altera/uighurs.html

- Manichaeism and Nestorian Christianity, H. J. Klimkeit, History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol.4, Part 2, 70

- Fu-Hsüeh, Yang. 1994. “On the Sha-chou Uighur Kingdom”. Central Asiatic Journal 38 (1). Harrassowitz Verlag: 80–107. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41929460.

Bibliography

- Asimov, M.S. (1998), History of civilizations of Central Asia Volume IV The age of achievement: A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century Part One The historical, social and economic setting, UNESCO Publishing

- Barfield, Thomas (1989), The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China, Basil Blackwell

- Benson, Linda (1998), China's last Nomads: the history and culture of China's Kazaks, M.E. Sharpe

- Bregel, Yuri (2003), An Historical Atlas of Central Asia, Brill

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (2000), The Age of Achievement: A.D. 750 to the End of the Fifteenth Century - Vol. 4, Part II : The Achievements (History of Civilizations of Central Asia), UNESCO Publishing

- Bughra, Imin (1983), The history of East Turkestan, Istanbul: Istanbul publications

- Drompp, Michael Robert (2005), Tang China And The Collapse Of The Uighur Empire: A Documentary History, Brill

- Golden, Peter B. (2011), Central Asia in World History, Oxford University Press

- Haywood, John (1998), Historical Atlas of the Medieval World, AD 600-1492, Barnes & Noble

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott (1964), The Chinese, their history and culture, Volumes 1-2, Macmillan

- Mackerras, Colin (1990), "Chapter 12 - The Uighurs", in Sinor, Denis (ed.), The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, Cambridge University Press, pp. 317–342, ISBN 0 521 24304 1

- Millward, James A. (2007), Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang, Columbia University Press

- Mackerras, Colin, The Uighur Empire: According to the T'ang Dynastic Histories, A Study in Sino-Uighur Relations, 744–840. Publisher: Australian National University Press, 1972. 226 pages, ISBN 0-7081-0457-6

- Rong, Xinjiang (2013), Eighteen Lectures on Dunhuang, Brill

- Sinor, Denis (1990), The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-24304-9

- Soucek, Svat (2000), A History of Inner Asia, Cambridge University Press

- Xiong, Victor (2008), Historical Dictionary of Medieval China, United States of America: Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 0810860538

- Xue, Zongzheng (1992), Turkic peoples, 中国社会科学出版社