Ein Karem

Ein Karem (Hebrew: עֵין כֶּרֶם, lit. "Spring of the Vineyard", and Arabic: عين كارم - ʿEin Kārem, or in literary Arabic ʿAyn Kārim;[9] also Ain Karem, Ein Kerem) is an ancient village southwest of historical Jerusalem, and now a neighbourhood of the modern city, within Jerusalem District, Israel. It is the site of the Hadassah Medical Center. It was a Palestinian town in Mandatory Palestine's Jerusalem Subdistrict, depopulated during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War on July 16, 1948.[10][11]

'Ayn Karim عين كارم | |

|---|---|

Village | |

Postcard from 'Ayn Karim, pre-1948 | |

| Etymology: 'Ain Kârim (Arabic): spring of the vinyard, generous spring,[1] spring of the dresser of the soil.[2] Ein Karem (Hebrew): spring of the vinyard.[1] | |

| Palestine grid | 165/130 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Jerusalem |

| Date of depopulation | 10 and 21 April 1948, 16 July 1948[3] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 15,029 dunams (15.029 km2 or 5.803 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 650 m (2,130 ft) |

| Population (1948[6]) | |

| • Total | 3,689 |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Influence of nearby town's fall |

| Secondary cause | Military assault by Yishuv forces |

| Current Localities | Ein Karem[7] Beit Zayit,[8] Even Sapir[8] |

Christian tradition holds that Saint John the Baptist was born in Ein Karem, this leading to the establishment of many churches and monasteries in the area. In 2010 the neighborhood had a population of 2,000.[12] It attracts three million visitors a year, one-third of them pilgrims from around the world.[12]

Etymology

The Arabic name can be translated as either "spring of the vinyard", which is identical to the Hebrew meaning of the name, or as "generous spring".[1]

History

A spring that provides water to the village of Ein Karem stimulated settlement there from an early time.[13]

Bronze Age

Pottery has been found near the spring dating to the Middle Bronze Age.[13]

Iron Age/Israelite period

During the Iron Age, or Israelite period, it could be identified as the location of Beth HaKerem[14] (Jeremiah 6:1; Nehemiah 3:14), where the name comes from.

Second Temple period

A well-preserved mikveh (Jewish ritual bath) indicates there was a Jewish settlement in the Second Temple period along with some other discoveries such as handful of graves, bits of a wall, and an olive press.[15][16] A reservoir here was mentioned in the Copper Scroll, one of the Dead Sea Scrolls.[17][18]

Roman and Byzantine periods

During excavations in the Church of Saint John the Baptist, a marble statue of Aphrodite (or Venus) was found, broken in two. It is believed to date from the Roman era and was probably toppled in Byzantine times. Today, the statue is at the Rockefeller Museum.[19] Excavations in front of the same church, which has at its core the cave which Christian tradition identifies as the birthplace of John the Baptist, have unearthed remains of two Byzantine chapels, one containing an inscription mentioning Christian "martyrs", but without any mention of John. Ceramics from the Byzantine period have also been found in Ein Karem.[20]

Sources from the Byzantine period are associating Ein Karem with the place where Elizabeth, the mother of John the Baptist, had lived, which is not properly named by the New Testament. In around 530 CE, the Christian pilgrim Theodosius places Elizabeth's town at a distance of five miles from Jerusalem,[21] which suits Ein Karem.

Early Islamic period

Ein Karem was recorded after the Islamic conquest. Al-Tamimi, the physician (d. 990), mentions a church in Ein Karem that was venerated by the Christians, also mentioning an old custom of the Jews of Ein Karem to make wreaths from the boughs (branches) of a wild plant belonging to the mint family (Lamiaceae) during the Jewish holiday of Shavu'ot.[22]

Crusader period

It is mentioned under the name St. Jehan de Bois, "Saint John in the Mountains",[9] during the Crusades. The Crusaders were the first to build here a church dedicated to St John, rebuilt in the 17th century by the Franciscans and still active today, and Moshe Sharon considers it as "almost sure" that the Crusaders are the ones who started the tradition of identifying that particular site as St John's birthplace.[23]

Mamluk period

A coin from the reign of As-Salih Hajji (1389 CE.) was found here, together with pottery, glassware and other coins from the Mamluk era.[24]

Ottoman period

Most of the village - some 15,000 dunams - was waqf land set aside charitably to benefit the Moroccan Muslim community in Jerusalem, belonging to the endowment established by Abu Madyan in the 14th century.[25]

In 1517, the village was included in the Ottoman empire with the rest of Palestine and in the 1596 tax-records it appeared as 'Ain Karim, located in the Nahiya of Jabal Quds of the Liwa of Al-Quds. The village had at this time 29 households, all Muslim. The villagers paid a fixed tax rate of 33.3% on agricultural products, which included wheat, barley, summer crops, vineyards, grape syrup/molasse, goats and beehives in addition to "occasional revenues"; a total of 5,300 akçe. All of the revenue went to a waqf.[26][27]

In the course 17th century, the Franciscans manage to recover the ruins of the church raised by the Crusaders over the traditional birth cave of St. John and, in spite of local Muslim opposition, to rebuild and fortify it as the Monastery of St. John in the Mountains.

James Silk Buckingham visited in the early 1800s, and found he was "more pleased with this village [...] than with any other place I had yet visited in Palestine."[28]

In 1838, Ain Karim was noted as a Muslim and Latin Christian village in the Beni Hasan district.[29][30]

In 1863 Victor Guérin noted a thousand inhabitants "of whom there are barely two hundred and fifty who are Catholics; the others are Muslim."[31] The ancestors of the latter were held to descend from Maghrabins, that is to say, originating from the Maghreb (North Africa).[32] Guérin describes them as rowdy and fanatical, until a few years before his visit having very often attacked the Catholic monks at the Monastery of St John in order to extort from them food and money, a habit that had subsided only lately.[32][9]

An official Ottoman village list from about 1870 showed that Ain Karim had 178 houses and a population of 533, though the population count included only men. The population consisted of 412 Muslims in 138 houses, 66 Latin Christians in 18 houses, and 55 Greek Christians in 12 houses.[33][34]

In 1883, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine (SWP) described Ain Karim as: "A flourishing village of about 600 inhabitants, 100 being Latin Christians. It stands on a sort of natural terrace projecting from the higher hills on the east of it, with a broad flat valley below on the west. On the south below the village is a fine spring ('Ain Sitti Miriam), with a vaulted place for prayer over it. The water issues from a spout into a trough."[35]

In 1896 the population of 'Ain karim was estimated to be about 1,290 persons.[36]

British Mandate period

In the 1922 census of Palestine, conducted by the British Mandate authorities, the population of 'Ain Karim was 1,735; consisting of 1,282 Muslims and 453 Christians,[37] increasing in the 1931 census to 2,637, in 555 houses.[38]

In the 1945 statistics, Ein Karim had a population of 3,180; 2,510 Muslims and 670 Christians,[39] The total land area was 15,029 dunams,[4] of this, a total of 7,960 dunums of land were irrigated or used for plantations, 1,199 were used for cereals;[40] while a total of 1,704 dunams were classified as built-up (urban) areas.[41]

The 1947 United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine placed 'Ayn Karim in the Jerusalem enclave intended for international control.[42] In February 1948 the village's 300 guerilla fighters were reinforced by a well-armed Arab Liberation Army force of mainly Syrian fighters, and on March 10 a substantial Iraqi detachment arrived in the village, followed within days by some 160 Egyptian fighters. On March 19, the villagers joined their foreign guests in attacking a Jewish convoy on the Tel Aviv-Jerusalem road.[43] Immediately after the April 1948 massacre at the nearby village of Deir Yassin (2 km to the north), most of the women and children in the village were evacuated.[44]

State of Israel

It was attacked by Israeli forces during the ten-day campaign of July 1948. The remaining civilian inhabitants fled on July 10–11. The Arab Liberation Army forces which had camped in the village left on July 14–16 after Jewish forces captured two dominating hilltops, Khirbet Beit Mazmil and Khirbet al-Hamama, and shelled the village. During its last days, 'Ayn Karim suffered from severe food shortages.[44]

Israel later incorporated the village into the municipal boundaries of Jerusalem.[44] Ein Kerem was one of the few depopulated Arab localities which survived the war with most of the buildings intact. The abandoned homes were resettled with new immigrants. Over the years, the bucolic atmosphere attracted a population of artisans and craftsmen.

In 1961, Hadassah built its medical center on a nearby hilltop, including the Hadassah Ein Kerem hospital and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem schools of medicine, dentistry, nursing, and pharmacology.[45]

Biblical connections

Old Testament

Only the Septuagint translation of the Hebrew Bible, the base for the Christian Old Testament, names a place in the hills of Judah as "Carem" (Joshua 15:30).[9][46]

New Testament

According to the New Testament, Mary went "into the hill country, to a city of Judah" (Luke 1:39) when she visited her cousin Elizabeth, the wife of Zechariah.

During the Byzantine period, Theodosius (530 CE) gives the distance between Jerusalem and the town of Elizabeth as five miles.[21]

The Jerusalem Calendar (Kalendarium Hyerosolimitanum) or the Georgian Festival Calendar, dated by some before 638, the year of the Muslim conquest, mentions the village by name, "Enqarim," as the place of a festival in memory of Elizabeth celebrated on the twenty-eighth of August.[47]

The English writer Saewulf, on pilgrimage to Palestine in 1102-1103, wrote of a monastery in the area of Ein Karim dedicated to St. Sabas, where 300 monks had been "slain by Saracens", but without mentioning any tradition connected to St. John.[23]

Landmarks

Church of the Visitation

The Church of the Visitation, or Abbey Church of St John in the Woods, is located across the village to the southwest from St. John's. The ancient sanctuary there was built against a rock declivity. It is venerated as the pietra del nascondimento, the "stone in which John was concealed," in reference to the Protevangelium of James. The site is also attributed to John the Baptist's parental summer house, where Mary visited them. The modern church was built in 1955, also on top of ancient church remnants. It was designed by Antonio Barluzzi, an Italian architect, who designed many other churches in the Holy Land during the 20th century.[48]

Monastery of St. John in the Mountains

The Catholic Monastery of St. John ba-Harim (St. John "in the Mountains"[49] in Hebrew) is centered on a church containing the cave identified by tradition as the birthplace of Saint John the Baptist. The church is built over the remnants of a Crusader church and its porch stands over the remains of two Byzantine chapels, both containing mosaic floors. The current structure received its outlook as the result of the latest large architectural intervention, finished in 1939 under the guidance of the Italian architect, Antonio Barluzzi.[50]

In 1941–1942 the Franciscans excavated the area west of the church and monastery. The southernmost of the rock-cut chambers they found can probably be dated to the first century CE.[51][52] Some remnants below the southern part of the porch suggests the presence of a mikve (Jewish ritual bath) that is dated to the Second Temple Period.

The church is mentioned in the Book of the Demonstration, attributed to Eutychius of Alexandria (940): "The church of Bayt Zakariya in the district of Aelia bears witness to the visit of Mary to her kinswoman Elizabeth."[53]

The site of the Crusader church built above the traditional birth cave of St John, destroyed after the departure of the Crusaders, was purchased by Franciscan custos, Father Thomas of Novara in 1621.[54][55] After a decades-long struggle with the Muslim inhabitants, the Fraciscans finally managed to rebuild and fortify their church and monastery by the 1690s.[56][57]

Convent of the Sisters of Zion

The monastery of Les Sœurs de Notre-Dame de Sion (Sisters of Our Lady of Zion), built in 1860,[9] was founded by two brothers from France, Theodore and Marie-Alphonse Ratisbonne, who were born Jewish and converted to Christianity.[58] They established an orphanage here. Alphonse himself lived in the monastery and is buried in its garden.

Gorny or "Moscobia" Convent

The convent was established by the Jerusalem mission of the Russian Orthodox Church in 1871[23] (see also Russian Wikipedia page here). The name "Gorny Convent" refers to the visit of the Virgin Mary to her cousin St. Elizabeth "into the hill country, to a town in Judah,"[59] gorny meaning mountainous in Russian. It was nicknamed "Muskobiya" (Arabic for Moscow) by the local Arab villagers, which mutated in Hebrew to "Moskovia." Apart from the structures serving the nunnery and a pilgrims hostel, it now contains three churches, enclosed within a compound wall. The Church of Our Lady of Kazan (Kazanskaya) is dedicated to the holy icon of Our Lady of Kazan and is the oldest among the three churches, being consecrated in 1873. The Cathedral of All Russian Saints, with its gilded domes, was started before the Russian Revolution and could only be completed in 2007. The cave church of St. John the Baptist was consecrated in 1987.

Mary's Spring

According to a Christian tradition which started in the 14th century, the Virgin Mary drank water from this village spring, and here is also the place where Mary and Elizabeth met. Therefore, since the 14th century the spring is known as the Fountain of the Virgin. The spring waters are considered holy by some Catholic and Orthodox Christian pilgrims who visit the site and fill their bottles. What looks like a spring is actually the end of an ancient aqueduct. The former Arab inhabitants built a mosque and school on the site, of which a Maqam (shrine) and minaret still remain. An inscribed panel to the courtyard of the mosque dates it to 1828-1829 CE (1244 H.)[60] The spring was repaired and renovated by Baron Edmond de Rothschild.[61]

St. Vincent

St. Vincent-Ein Kerem is a home for physically or mentally handicapped children. Founded in 1954, St. Vincent-Ein Kerem is a non-profit enterprise under leadership of the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul.[62]

Other churches and religious institutions

Catholic

Greek Orthodox

- The Greek Orthodox Church of St John,[49] built in 1894 on the remnants of an ancient church

Related sites in the area

Monastery of St. John in the Wilderness

The Monastery of St. John in the Wilderness, containing a cave associated with the saint, is located in the nearby moshav Even Sapir.

Notable residents

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ein Kerem. |

- 1948 Palestine War

- Beit HaKerem, a biblical fortress in Judah identified with either the later Herodium site, Ramat Rachel, or Ein Karem

- Carem, a town mentioned only in the Septuagint

- Ein Kerem Agricultural School

- List of Arab towns and villages depopulated during the 1948 Palestinian exodus

- List of villages depopulated during the Arab–Israeli conflict

- Hadassah Medical Center

References

- Guérin, 1868, pp. 84-85

- Palmer, 1881, p. 280

- Morris, 2004, p. xx, village #360. Also gives the cause for depopulation

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 57

- Ein Karem Elevation (649.83 M), on Distancesto.com

- Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics Depopulated Jerusalem Localities of the year 1948 by Selected Variables

- Morris, 2004, p. xxii, settlement #107. 1949

- Khalidi, 1992, p. 273

- Sharon, 2004, p. 155

- Morris, 2004, p. xx, village #360. Also gives cause of depopulation.

- "'Ayn Karim - عين كارم -Jerusalem - Palestine Remembered". www.palestineremembered.com. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Dvir, Noam (25 August 2010). "Ein Karem Under Threat". Haaretz. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- G. Ernest Wright, Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 71 [Oct. 1938], pp. 28f

- Carta's Official Guide to Israel and Complete Gazetteer to all Sites in the Holy Land. (3rd edition 1993) Jerusalem, Carta, p.233, ISBN 965-220-186-3 (English)

- "Jerusalem family finds 2,000-year-old ritual bath under living room". timesofisrael.com. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Re'em, 2016, Jerusalem, ‘En Kerem

- Tsafrir, Di Segni and Green, 1994, p. 82

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-03-14. Retrieved 2017-09-09.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) (line 46)

- "Ein Kerem". My Holy Land. Archived from the original on 2011-07-14. Retrieved 2007-11-08.

- Dauphin, 1998, p. 906

- Theodosius, 1893, p. 10

- Zohar Amar and Yaron Serri, The Land of Israel and Syria as Described by al-Tamimi – Jerusalem Physician of the 10th Century, Ramat-Gan 2004, p. 26 ISBN 965-226-252-8 (Hebrew)

- Sharon, 2004, p. 156

- Landes-Nagar, 2017, Jerusalem, ʽEn Kerem

- Kark & Oren-Nordheim 2001, p. 212.

- Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 118

- NB: Clerical persons, whether Muslim, Jewish or Christian, were not included

- Buckingham, 1821, pp. 227-229

- Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol. 3, 2nd appendix, p. 123

- Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol. 2, pp. 141, 157

- Guérin, 1868, pp. 83-96

- Guérin, 1868, p. 84

- Socin, 1879, p. 143. It was also noted to be in the Beni Hasan district

- Hartmann, 1883, p. 122 noted 144 houses

- Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, pp. 19-21

- Schick, 1896, p. 125

- Barron, 1923, Table VII, Sub-district of Jerusalem, p. 14

- Mills, 1932, p. 39

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 24

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 102

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 152

- UN map of Jerusalem Corpus Separatum Archived 2006-12-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Efraim Karsh, Palestine Betrayed (2010) p182.

- Morris, 2004, p. 436, quoting: Entries for 10 and 11 July 1948, General Staff∖Operations Logbook, IDFA∖922∖75∖∖1176; and Mordechai Abir, ´The local Arab Factor in the War of Independence (Jerusalem Area)`18-19, IDFA 1046∖70∖185∖∖; and Yeruham, `Arab Information (from 14.7.48)´, 15 July 1948 HA 105∖127aleph.

- "Hadassah opens new pediatric bone marrow transplantation unit - Israel News - Jerusalem Post". www.jpost.com. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- Guérin, 1869, pp. 2-3

- Sharon, 2004, p. 157

- Pringle, 1993, pp. 38–46

- The Ain Karem Casa Nova is Back, Custodia Terrae Sanctae, 30 April 2014, accessed 21 May 2019

- Ain Karem: Saint John the Baptist, at custodia.org, accessed 21 May 2019

- Abel, 1938, pp. 295f

- Pringle, 1993, pp. 30–38

- Jack Finegan (2014). The Archeology of the New Testament: The Life of Jesus and the Beginning of the Early Church (revised ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 4. ISBN 9781400863181. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- Pringle, 1993, p. 32

- Sharon, 2004, p. 156

- Sharon, 2004, pp. 156-157

- Maundrell, 1703, p. 92

- "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Maria Alphonse Ratisbonne". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- "Bible Gateway passage: Luke 1:39-56 - New International Version". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Petersen, 2001 pp. 100-103

- טיולי, אתר. "ירושלים עין כרם - אתר טיולי". tiuli.com. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Sisters of mercy Haaretz, 8 November 2007

Bibliography

- Abel, F.M. (1938). Geographie de la Palestine. 2 Geographie Politique. Les villes. Librairie Lecoffre.

- Avner, Rina (2006-01-08). "Jerusalem, 'En Kerem" (118). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Buckingham, J.S. (1821). Travels in Palestine Through the Countries of Bashan and Gilead, East of the River Jordan, Including a Visit to the Cities of Geraza and Gamala in the Decapolis. London: Longman.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Dauphin, Claudine (1998). La Palestine byzantine, Peuplement et Populations. BAR International Series 726 (in French). III : Catalogue. Oxford: Archeopress. ISBN 0-860549-05-4.

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Guérin, V. (1868). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 1: Judee, pt. 1. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Guérin, V. (1869). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 1: Judee, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Centre.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Kark, R.; Oren-Nordheim, Michal (2001). Jerusalem and Its Environs: Quarters, Neighborhoods, Villages, 1800-1948. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-814-32909-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Landes-Nagar, Annette (2017-05-14). "Jerusalem, 'En Kerem" (129). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Petersen, Andrew (2001). A Gazetteer of Buildings in Muslim Palestine (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology). 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-727011-0.

- Pringle, Denys (1993). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: A-K (excluding Acre and Jerusalem). I. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39036-2.

- Radashkovsky, Igal (2018-02-27). "Jerusalem, 'En Kerem" (130). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Re'em, Amit (2016-06-05). "Jerusalem, 'En Kerem" (128). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 2. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Schick, C. (1896). "Zur Einwohnerzahl des Bezirks Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 19: 120–127.

- Schick C. (1899). "Ancient Rock-cut Wine-presses at 'Ain Karim". Quarterly Statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 31: 41–42.

- Schick C. (1905). "The birthplace of St. John the Baptist". Quarterly Statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 37: 61–69.

- Sharon, M. (2004). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, D-F. 3. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-13197-3.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

- Theodosius (1893). Theodosius (A.D. 530). Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society.

- Tobler, T. (1854). Dr. Titus Toblers zwei Bucher Topographie von Jerusalem und seinen Umgebungen (in German). 2. Berlin: G. Reimer. pp. 344 ff)

- Tsafrir, Y.; Leah Di Segni; Judith Green (1994). (TIR): Tabula Imperii Romani: Judaea, Palaestina. Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities. ISBN 965-208-107-8.

Further reading

- Olivier Rota, « L’exode arabe d’Eïn-Kerem en 1948. La relation des événements par les sœurs de Notre-Dame de Sion, St. Jean in Montana », in Tsafon, n°46, winter 2003, pp. 179–195.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Jerusalem/Ein Kerem. |

- Welcome To 'Ayn Karim, from Palestine Remembered

- Ayn Karim, Zochrot

- Ein Kerem (Karem), biblewalks

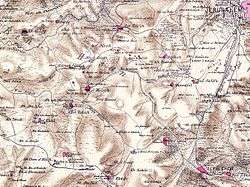

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 17: IAA, Wikimedia commons