Russian Orthodox Church

The Russian Orthodox Church (ROC; Russian: Ру́сская правосла́вная це́рковь, tr. Rússkaya pravoslávnaya tsérkov), alternatively legally known as the Moscow Patriarchate (Russian: Моско́вский патриарха́т, tr. Moskóvskiy patriarkhát),[14] is one of the autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Christian churches. The primate of the ROC is the Patriarch of Moscow and all Rus'. The ROC, as well as its primate, officially ranks fifth in the Orthodox order of precedence, immediately below the four ancient patriarchates of the Greek Orthodox Church: Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem.[15] As of October 15, 2018, the ROC suspended communion with the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, having unilaterally severed ties in reaction to the establishment of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine, which was finalised by the Ecumenical Patriarchate on 5 January 2019.

Russian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) | |

|---|---|

| Russian: Ру́сская правосла́вная це́рковь | |

| |

| Abbreviation | ROC |

| Classification | Eastern Orthodox |

| Orientation | Russian Orthodoxy |

| Scripture | Septuagint, New Testament |

| Theology | Eastern Orthodox theology |

| Polity | Episcopal |

| Governance | Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church |

| Structure | Communion |

| Primate | Patriarch Kirill of Moscow |

| Bishops | 382 (2019)[1] |

| Clergy | 40 514 full-time clerics, including 35 677 presbyters and 4837 deacons[1] |

| Parishes | 38 649 (2019)[1] |

| Dioceses | 314 (2019)[2] |

| Monasteries | 972 (474 male and 498 female) (2019)[1] |

| Associations | World Council of Churches[3] |

| Language | Church Slavonic, local languages |

| Liturgy | Byzantine Rite |

| Headquarters | Danilov Monastery, Moscow, Russia 55°42′40″N 37°37′45″E |

| Founder | Saint Vladimir the Great[4][5][lower-alpha 1] |

| Origin | 988 Kievan Rus', Ruthenia |

| Independence | 1448, de facto [8] |

| Recognition | 1589, by Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople 1593, by Pan-Orthodox Synod of Patriarchs at Constantinople |

| Separations | Old Believers (mid-17th century) Catacomb Church (1925) True Russian Orthodox Church (2007; very small) |

| Members | 112 million (100 million in Russia, total of 12 million in the linked autonomous churches[9][10][11][12][13] |

| Other name(s) | Russian Church Moscow Patriarchate |

| Official website | patriarchia.ru |

The Christianization of Kievan Rus', widely seen as the birth of the ROC, is believed to have occurred in 988 through the baptism of the Kievan prince Vladimir and his people by the clergy of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, whose constituent part the ROC remained for the next six centuries, while the Kievan see remained in the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate until 1686.

The ROC currently claims exclusive jurisdiction over the Orthodox Christians, irrespective of their ethnic background, who reside in the former member republics of the Soviet Union, excluding Georgia and Armenia. Such countries as Estonia, Moldova, and Ukraine dispute this claim and have established parallel canonical Orthodox jurisdictions: the Estonian Apostolic Orthodox Church, the Metropolis of Bessarabia, and the Orthodox Church of Ukraine, respectively. The ROC also exercises ecclesiastical jurisdiction over the autonomous Church of Japan and the Orthodox Christians resident in the People's Republic of China. The ROC branches in Belarus, Estonia, Latvia, Moldova and Ukraine since the fall of the Soviet Union in the 1990s enjoy various degrees of self-government, albeit short of the status of formal ecclesiastical autonomy.

The ROC should not be confused with the Orthodox Church in America (OCA). It has been an autocephalous Orthodox church since 1970, but it is not universally recognised in this status. The Ecumenical Patriarchate views it as a branch of the ROC. It traces its history in North America to the late 18th century, when Russian missionaries in Alaska (then part of the Russian Empire) first established churches among the Alaska Natives and other indigenous peoples.

The ROC should also not be confused with the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (also known as the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, or ROCOR), headquartered in the United States. The ROCOR was instituted in the 1920s by Russian communities outside Communist Russia, which had refused to recognize the authority of the Moscow Patriarchate that was de facto headed by Metropolitan Sergius Stragorodsky. The two churches reconciled on 17 May 2007; the ROCOR is now a self-governing part of the Russian Orthodox Church.

History

Kievan period

The Christian community that developed into what is now known as the Russian Orthodox Church is traditionally said to have been founded by the Apostle Andrew, who is thought to have visited Scythia and Greek colonies along the northern coast of the Black Sea. According to one of the legends, Andrew reached the future location of Kiev and foretold the foundation of a great Christian city.[16][17] The spot where he reportedly erected a cross is now marked by St. Andrew's Cathedral.

By the end of the first millennium AD, eastern Slavic lands started to come under the cultural influence of the Eastern Roman Empire. In 863–69, the Byzantine monks Saint Cyril and Saint Methodius, both from the region of Macedonia in the Eastern Roman Empire translated parts of the Bible into the Old Church Slavonic language for the first time, paving the way for the Christianization of the Slavs and Slavicized peoples of Eastern Europe, the Balkans, Northern Russia, Southern Russia and Central Russia. There is evidence that the first Christian bishop was sent to Novgorod from Constantinople either by Patriarch Photius or Patriarch Ignatios, c. 866–867.

By the mid-10th century, there was already a Christian community among Kievan nobility, under the leadership of Bulgarian and Byzantine priests, although paganism remained the dominant religion. Princess Olga of Kiev was the first ruler of Kievan Rus′ who became a Christian. Her grandson, Vladimir of Kiev, made Rus' officially a Christian state. The official Christianization of Kievan Rus' is widely believed to have occurred in 988 AD, when Prince Vladimir was baptised himself and ordered his people to be baptised by the priests from the Eastern Roman Empire.

The Kievan church was a junior metropolitanate of the Patriarchate of Constantinople and the Ecumenical Patriarch appointed the metropolitan, who usually was a Greek, who governed the Church of Rus'. The Kiev Metropolitan's residence was originally located in Kiev itself, the capital of the medieval Rus' state.

Transfer of the see to Moscow; de facto independence of the Moscow Church

As Kiev was losing its political, cultural, and economical significance due to the Mongol invasion, Metropolitan Maximus moved to Vladimir in 1299; his successor, Metropolitan Peter moved the residence to Moscow in 1325.

Following the tribulations of the Mongol invasion, the Russian Church was pivotal in the survival and life of the Russian state. Despite the politically motivated murders of Mikhail of Chernigov and Mikhail of Tver, the Mongols were generally tolerant and even granted tax exemption to the church. Such holy figures as Sergius of Radonezh and Metropolitan Alexis helped the country to withstand years of Mongol rule, and to expand both economically and spiritually. The Trinity monastery north of Moscow founded by Sergius of Radonezh became the setting for the flourishing of spiritual art, exemplified by the work of Andrey Rublev, among others. The followers of Sergius founded four hundred monasteries, thus greatly extending the geographical extent of the Grand Duchy of Moscow.

In 1439, at the Council of Florence, some Orthodox hierarchs from Byzantium as well as Metropolitan Isidore, who represented the Russian Church, signed a union with the Roman Church, whereby the Eastern Church would recognise the primacy of the Pope. However, the Moscow Prince Vasili II rejected the act of the Council of Florence brought to Moscow by Isidore in March 1441. Isidore was in the same year removed from his position as an apostate and expelled from Moscow. The Russian metropolitanate remained effectively vacant for the next few years due largely to the dominance of Uniates in Constantinople then. In December 1448, Jonas, a Russian bishop, was installed by the Council of Russian bishops in Moscow as Metropolitan of Kiev and All Russia[18] (with permanent residence in Moscow) without the consent from Constantinople. This occurred five years prior to the fall of Constantinople in 1453 and, unintentionally, signified the beginning of an effectively independent church structure in the Moscow (North-Eastern Russian) part of the Russian Church. Subsequently, there developed a theory in Moscow that saw Moscow as the Third Rome, the legitimate successor to Constantinople, and the Primate of the Moscow Church as head of all the Russian Church. Meanwhile, the newly established in 1458 Russian Orthodox (initially Uniate) metropolitanate in Kiev (then in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and subsequently in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth) continued under the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical See until 1686, when it was transferred to the jurisdiction of Moscow.

The reign of Ivan III and his successor was plagued by a number of heresies and controversies. One party, led by Nil Sorsky and Vassian Kosoy, called for the secularisation of monastic properties. They were opposed by the influential Joseph of Volotsk, who defended ecclesiastical ownership of land and property. The sovereign's position fluctuated, but eventually he threw his support to Joseph. New sects sprang up, some of which showed a tendency to revert to Mosaic law: for instance, the archpriest Aleksei converted to Judaism after meeting a certain Zechariah the Jew.

In the 1540s, Metropolitan Macarius codified Russian hagiography and convened a number of church synods, which culminated in the Hundred Chapter Council of 1551. This Council unified church ceremonies and duties throughout the Moscow Church. At the demand of the church hierarchy, the government lost its jurisdiction over ecclesiastics. Reinforced by these reforms, the Moscow Church felt powerful enough to occasionally challenge the policies of the tsar. Metropolitan Philip, in particular, decried the abuses of Ivan the Terrible, who eventually engineered his deposition and murder.

Autocephaly and schism

During the reign of Tsar Fyodor I his brother-in-law Boris Godunov contacted the Ecumenical Patriarch, who "was much embarrassed for want of funds,"[19] with a view to establishing a patriarchal see in Moscow. As a result of Godunov's efforts, Metropolitan Job of Moscow became in 1589 the first Patriarch of Moscow and All Rus', making the Russian Church autocephalous. The four other patriarchs have recognized the Moscow Patriarchate as one of the five honourable Patriarchates. During the next half a century, when the tsardom was weak, the patriarchs (notably Hermogenes and Philaret) would help run the state along with (and sometimes instead of) the tsars.

At the urging of the Zealots of Piety, in 1652 Patriarch Nikon of Moscow resolved to centralize power that had been distributed locally, while conforming Russian Orthodox rites and rituals to those of the Greek Orthodox Church, as interpreted by pundits from the Kiev Ecclesiastical Academy. For instance, he insisted that Russian Christians cross themselves with three fingers, rather than the then-traditional two. This aroused antipathy among a substantial section of believers, who saw the changed rites as heresy, although the extent to which these changes can be regarded as minor or major ritual significance remains open to debate. After the implementation of these innovations at the church council of 1666–1667, the church anathematized and suppressed those who acted contrary to them with the support of Muscovite state power. These traditionalists became known as "Old Believers" or "Old Ritualists".

Although Nikon's far-flung ambitions of steering the country to a theocratic form of government precipitated his defrocking and exile, Tsar Aleksey deemed it reasonable to uphold many of his innovations. During the Schism of the Russian Church, the Old Ritualists were separated from the main body of the Orthodox Church. Archpriest Avvakum Petrov and many other opponents of the church reforms were burned at the stake, either forcibly or voluntarily. Another prominent figure within the Old Ritualists' movement, Boyarynya Morozova, was starved to death in 1675. Others escaped from the government persecutions to Siberia.

Several years after the Council of Pereyaslav (1654) that heralded the subsequent incorporation of eastern regions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth into the Tsardom of Russia, the see of the Metropolitan of Kiev and all Rus' was transferred to the Moscow Patriarchate (1686).

Peter the Great

Peter the Great (1682–1725) had an agenda of radical modernization of Russian government, army, dress and manners. He made Russia a formidable political power. Peter was not religious and had a low regard for the Church, so he put it under tight governmental control. He replaced the Patriarch with a Holy Synod, which he controlled. The Tsar appointed all bishops. A clerical career was not a route chosen by upper-class society. Most parish priests were sons of priests, were very poorly educated, and very poorly paid. The monks in the monasteries had a slightly higher status; they were not allowed to marry. Politically, the church was impotent. Catherine the Great later in the 18th century seized most of the church lands, and put the priests on a small salary supplemented by fees for services such as baptism and marriage.[20]

Expansion

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the Russian Orthodox Church experienced a vast geographic expansion. Numerous financial and political incentives (as well as immunity from military service) were offered local political leaders who would convert to Orthodoxy, and bring their people with them.

In the following two centuries, missionary efforts stretched out across Siberia into Alaska. Eminent people on that missionary effort included St. Innocent of Irkutsk and St. Herman of Alaska. In emulation of Stephen of Perm, they learned local languages and translated gospels and hymns. Sometimes those translations required the invention of new systems of transcription.

.jpg)

In the aftermath of the Treaty of Pereyaslav, the Ottomans (supposedly acting on behalf of the Russian regent Sophia Alekseyevna) pressured the Patriarch of Constantinople into transferring the Metropolis of Kiev from the jurisdiction of Constantinople to that of Moscow. The handover brought millions of faithful and half a dozen dioceses under the ultimate administrative care of the Patriarch of Moscow and all Rus' (and later of the Holy Synod of Russia), leading to the significant Ukrainian presence in the Russian Church, which continued well into the 18th century, with Theophanes Prokopovich, Epiphanius Slavinetsky, Stephen Yavorsky and Demetrius of Rostov being among the most notable representatives of this trend.[21] The exact terms and conditions of the handover of the Kiev Metropolis are a contested issue.[22][23][24][25]

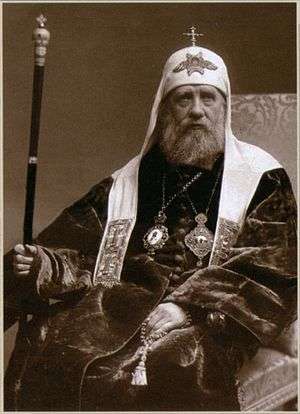

In 1700, after Patriarch Adrian's death, Peter the Great prevented a successor from being named, and in 1721, following the advice of Feofan Prokopovich, Archbishop of Pskov, the Holy and Supreme Synod was established under Archbishop Stephen Yavorsky to govern the church instead of a single primate. This was the situation until shortly after the Russian Revolution of 1917, at which time the Local Council (more than half of its members being lay persons) adopted the decision to restore the Patriarchate. On 5 November (according to the Julian calendar) a new patriarch, Tikhon, was named through casting lots.

The late 18th century saw the rise of starchestvo under Paisiy Velichkovsky and his disciples at the Optina Monastery. This marked a beginning of a significant spiritual revival in the Russian Church after a lengthy period of modernization, personified by such figures as Demetrius of Rostov and Platon of Moscow. Aleksey Khomyakov, Ivan Kireevsky and other lay theologians with Slavophile leanings elaborated some key concepts of the renovated Orthodox doctrine, including that of sobornost. The resurgence of Eastern Orthodoxy was reflected in Russian literature, an example is the figure of Starets Zosima in Fyodor Dostoyevsky's Brothers Karamazov.

Fin-de-siècle religious renaissance

During the final decades of the imperial order in Russia many educated Russians sought to return to the church and tried to bring their faith back to life. No less evident were non-conformist paths of spiritual searching known as "God-Seeking". Writers, artists and intellectuals in large numbers were drawn to private prayer, mysticism, spiritualism, theosophy and Eastern religions. A fascination with primitive feeling, with the unconscious and the mythic was apparent, along with visions of coming catastrophes and redemption.

In 1909, a volume of essays appeared under the title Vekhi ("Milestones" or "Landmarks"), authored by a group of leading left-wing intellectuals, including Sergei Bulgakov, Peter Struve and former Marxists. They bluntly repudiated the materialism and atheism that had dominated the thought of the intelligentsia for generations as leading inevitably to failure and moral disaster. The essays created a sensation.

It is possible to see a similarly renewed vigor and variety in religious life and spirituality among the lower classes, especially after the upheavals of 1905. Among the peasantry there was widespread interest in spiritual-ethical literature and non-conformist moral-spiritual movements, an upsurge in pilgrimage and other devotions to sacred spaces and objects (especially icons), persistent beliefs in the presence and power of the supernatural (apparitions, possession, walking-dead, demons, spirits, miracles and magic), the renewed vitality of local "ecclesial communities" actively shaping their own ritual and spiritual lives, sometimes in the absence of clergy, and defining their own sacred places and forms of piety. Also apparent was the proliferation of what the Orthodox establishment branded as "sectarianism", including both non-Orthodox Christian denominations, notably Baptists, and various forms of popular Orthodoxy and mysticism.[26]

Russian revolution and Civil War

In 1914, there were 55,173 Russian Orthodox churches and 29,593 chapels, 112,629 priests and deacons, 550 monasteries and 475 convents with a total of 95,259 monks and nuns in Russia.[27]

The year 1917 was a major turning point in Russian history, and also the Russian Orthodox Church.[28] In early March 1917 (O.S.), the Czar was forced to abdicate, the Russian empire began to implode, and the government's direct control of the Church was all but over by August 1917. On 15 August (O.S.), in the Moscow Dormition Cathedral in the Kremlin, the Local (Pomestniy) Council of the ROC, the first such convention since the late 17th century, opened. The council continued its sessions until September 1918 and adopted a number of important reforms, including the restoration of Patriarchate, a decision taken 3 days after the Bolsheviks overthrew the Provisional Government in Petrograd on 25 October (O.S.). On 5 November, Metropolitan Tikhon of Moscow was selected as the first Russian Patriarch after about 300 years of the Synodal rule.

In early February 1918, the Bolshevik-controlled government of Soviet Russia enacted the Decree on separation of church from state and school from church that proclaimed separation of church and state in Russia, freedom to "profess any religion or profess none", deprived religious organisations of the right to own any property and legal status. Legal religious activity in the territories controlled by Bolsheviks was effectively reduced to services and sermons inside church buildings. The Decree and attempts by Bolshevik officials to requisition church property caused sharp resentment on the part of the ROC clergy and provoked violent clashes on some occasions: on 1 February (19 January O.S.), hours after the bloody confrontation in Petrograd's Alexander Nevsky Lavra between the Bolsheviks trying to take control of the monastery's premises and the believers, Patriarch Tikhon issued a proclamation that anathematised the perpetrators of such acts.[29]

The church was caught in the crossfire of the Russian Civil War that began later in 1918, and church leadership, despite their attempts to be politically neutral (from the autumn of 1918), as well as the clergy generally were perceived by the Soviet authorities as a "counter-revolutionary" force and thus subject to suppression and eventual liquidation.

In the first five years after the Bolshevik revolution, 28 bishops and 1,200 priests were executed.[30]

Under Soviet rule

The Soviet Union, formally created in December 1922, was the first state to have elimination of religion as an ideological objective espoused by the country's ruling political party. Toward that end, the Communist regime confiscated church property, ridiculed religion, harassed believers, and propagated materialism and atheism in schools. Actions toward particular religions, however, were determined by State interests, and most organized religions were never outlawed.

Orthodox clergy and active believers were treated by the Soviet law-enforcement apparatus as anti-revolutionary elements and were habitually subjected to formal prosecutions on political charges, arrests, exiles, imprisonment in camps, and later could also be incarcerated in mental hospitals.[31][32]

Thousands of church buildings and initially all the monasteries were taken over by the Soviet government and either destroyed or converted to secular use. It was impossible to build new churches. Practising Orthodox Christians were restricted from prominent careers and membership in communist organizations (the party, the Komsomol). Anti-religious propaganda was openly sponsored and encouraged by the government, which the Church was not given an opportunity to publicly respond to. The government youth organization, the Komsomol, encouraged its members to vandalize Orthodox churches and harass worshippers. Seminaries were closed down, and the church was restricted from using the press. Theological schools were closed (until some were re-opened in the latter 1940s), and church publications were suppressed.

However, the Soviet policy vis-a-vis organised religion vacillated over time between, on the one hand, a utopian determination to substitute secular rationalism for what they considered to be an outmoded "superstitious" worldview and, on the other, pragmatic acceptance of the tenaciousness of religious faith and institutions. In any case, religious beliefs and practices did persist, not only in the domestic and private spheres but also in the scattered public spaces allowed by a state that recognized its failure to eradicate religion and the political dangers of an unrelenting culture war.[33]

The Russian Orthodox church was drastically weakened in May 1922, when the Renovated (Living) Church, a reformist movement backed by the Soviet secret police, broke away from Patriarch Tikhon (also see the Josephites and the Russian True Orthodox Church), a move that caused division among clergy and faithful that persisted until 1946.

The sixth sector of the OGPU, led by Yevgeny Tuchkov, began aggressively arresting and executing bishops, priests, and devout worshippers, such as Metropolitan Veniamin in Petrograd in 1922 for refusing to accede to the demand to hand in church valuables (including sacred relics). In the time between 1927 and 1940, the number of Orthodox Churches in the Russian Republic fell from 29,584 to less than 500. Between 1917 and 1935, 130,000 Orthodox priests were arrested. Of these, 95,000 were put to death. Many thousands of victims of persecution became recognized in a special canon of saints known as the "new martyrs and confessors of Russia".

When Patriarch Tikhon died in 1925, the Soviet authorities forbade patriarchal election. Patriarchal locum tenens (acting Patriarch) Metropolitan Sergius (Stragorodsky, 1887–1944), going against the opinion of a major part of the church's parishes, in 1927 issued a declaration accepting the Soviet authority over the church as legitimate, pledging the church's cooperation with the government and condemning political dissent within the church. By this declaration Sergius granted himself authority that he, being a deputy of imprisoned Metropolitan Peter and acting against his will, had no right to assume according to the XXXIV Apostolic canon, which led to a split with the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia abroad and the Russian True Orthodox Church (Russian Catacomb Church) within the Soviet Union, as they allegedly remained faithful to the Canons of the Apostles, declaring the part of the church led by Metropolitan Sergius schism, sometimes coined Sergianism. Due to this canonical disagreement it is disputed which church has been the legitimate successor to the Russian Orthodox Church that had existed before 1925.[34][35][36][37]

In 1927, Metropolitan Eulogius (Georgiyevsky) of Paris broke with the ROCOR (along with Metropolitan Platon (Rozhdestvensky) of New York, leader of the Russian Metropolia in America). In 1930, after taking part in a prayer service in London in supplication for Christians suffering under the Soviets, Evlogy was removed from office by Sergius and replaced. Most of Evlogy's parishes in Western Europe remained loyal to him; Evlogy then petitioned Ecumenical Patriarch Photius II to be received under his canonical care and was received in 1931, making a number of parishes of Russian Orthodox Christians outside Russia, especially in Western Europe an Exarchate of the Ecumenical Patriarchate as the Archdiocese of Russian Orthodox churches in Western Europe.

Moreover, in the 1929 elections, the Orthodox Church attempted to formulate itself as a full-scale opposition group to the Communist Party, and attempted to run candidates of its own against the Communist candidates. Article 124 of the 1936 Soviet Constitution officially allowed for freedom of religion within the Soviet Union, and along with initial statements of it being a multi-candidate election, the Church again attempted to run its own religious candidates in the 1937 elections. However the support of multicandidate elections was retracted several months before the elections were held and in neither 1929 nor 1937 were any candidates of the Orthodox Church elected.[38]

After Nazi Germany's attack on the Soviet Union in 1941, Joseph Stalin revived the Russian Orthodox Church to intensify patriotic support for the war effort. On 4 September 1943, Metropolitans Sergius (Stragorodsky), Alexius (Simansky) and Nicholas (Yarushevich) had a meeting with Stalin and received a permission to convene a council on 8 September 1943, which elected Sergius Patriarch of Moscow and all the Rus'. This is considered by some as violation of the XXX Apostolic canon, as no church hierarch could be consecrated by secular authorities.[34] A new patriarch was elected, theological schools were opened, and thousands of churches began to function. The Moscow Theological Academy Seminary, which had been closed since 1918, was re-opened.

In December 2017, the Security Service of Ukraine lifted classified top secret status of documents revealing that the NKVD of the USSR and its units were engaged in the selection of candidates for participation in the 1945 Local Council from the representatives of the clergy and the laity. NKVD demanded "to outline persons who have religious authority among the clergy and believers, and at the same time checked for civic or patriotic work". In the letter sent in September 1944, it was emphasized: "It is important to ensure that the number of nominated candidates is dominated by the agents of the NKBD, capable of holding the line that we need at the Council".[39][40]

Between 1945 and 1959 the official organization of the church was greatly expanded, although individual members of the clergy were occasionally arrested and exiled. The number of open churches reached 25,000. By 1957 about 22,000 Russian Orthodox churches had become active. But in 1959 Nikita Khrushchev initiated his own campaign against the Russian Orthodox Church and forced the closure of about 12,000 churches. By 1985 fewer than 7,000 churches remained active. Members of the church hierarchy were jailed or forced out, their places taken by docile clergy, many of whom had ties with the KGB. This decline was evident from the dramatic decay of many of the abandoned churches and monasteries that were previously common in even the smallest villages from the pre-revolutionary period.

Persecution under Khrushchev

A new and widespread persecution of the church was subsequently instituted under the leadership of Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev. A second round of repression, harassment and church closures took place between 1959 and 1964 when Nikita Khrushchev was in office. The number of Orthodox churches fell from around 22,000 in 1959 to around 8,000 in 1965;[41] priests, monks and faithful were killed or imprisoned and the number of functioning monasteries was reduced to less than twenty.

Subsequent to Khrushchev's overthrow, the Church and the government remained on unfriendly terms until 1988. In practice, the most important aspect of this conflict was that openly religious people could not join the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, which meant that they could not hold any political office. However, among the general population, large numbers remained religious.

Some Orthodox believers and even priests took part in the dissident movement and became prisoners of conscience. The Orthodox priests Gleb Yakunin, Sergiy Zheludkov and others spent years in Soviet prisons and exile for their efforts in defending freedom of worship.[42] Among the prominent figures of that time were Father Dmitri Dudko[43] and Father Aleksandr Men. Although he tried to keep away from practical work of the dissident movement intending to better fulfil his calling as a priest, there was a spiritual link between Fr Aleksandr and many of the dissidents. For some of them he was a friend; for others, a godfather; for many (including Yakunin), a spiritual father.[44]

By 1987 the number of functioning churches in the Soviet Union had fallen to 6,893 and the number of functioning monasteries to just 18. In 1987 in the Russian SFSR, between 40% and 50% of newborn babies (depending on the region) were baptized. Over 60% of all deceased received Christian funeral services.

Glasnost and evidence of KGB links

Beginning in the late 1980s, under Mikhail Gorbachev, the new political and social freedoms resulted in many church buildings being returned to the church, to be restored by local parishioners. A pivotal point in the history of the Russian Orthodox Church came in 1988, the millennial anniversary of the Baptism of Kievan Rus'. Throughout the summer of that year, major government-supported celebrations took place in Moscow and other cities; many older churches and some monasteries were reopened. An implicit ban on religious propaganda on state TV was finally lifted. For the first time in the history of the Soviet Union, people could see live transmissions of church services on television.

Gleb Yakunin, a critic of the Moscow Patriarchate who was one of those who briefly gained access to the KGB archive documents in the early 1990s, argued that the Moscow Patriarchate was "practically a subsidiary, a sister company of the KGB".[45] Critics charge that the archives showed the extent of active participation of the top ROC hierarchs in the KGB efforts overseas.[46][47][48][49][50][51] George Trofimoff, the highest-ranking US military officer ever indicted for, and convicted of, espionage by the United States and sentenced to life imprisonment on 27 September 2001, had been "recruited into the service of the KGB"[52] by Igor Susemihl (a.k.a. Zuzemihl), a bishop in the Russian Orthodox Church (subsequently, a high-ranking hierarch—the ROC Metropolitan Iriney of Vienna, who died in July 1999[53]).

Konstanin Kharchev, former chairman of the Soviet Council on Religious Affairs, explained: "Not a single candidate for the office of bishop or any other high-ranking office, much less a member of Holy Synod, went through without confirmation by the Central Committee of the CPSU and the KGB".[49] Professor Nathaniel Davis points out: "If the bishops wished to defend their people and survive in office, they had to collaborate to some degree with the KGB, with the commissioners of the Council for Religious Affairs, and with other party and governmental authorities".[54] Patriarch Alexy II, acknowledged that compromises were made with the Soviet government by bishops of the Moscow Patriarchate, himself included, and publicly repented of these compromises.[55]

Post-Soviet recovery and problems

Under Patriarch Aleksey II (1990–2008)

Metropolitan Alexy (Ridiger) of Leningrad, ascended the patriarchal throne in 1990 and presided over the partial return of Orthodox Christianity to Russian society after 70 years of repression, transforming the ROC to something resembling its pre-communist appearance; some 15,000 churches had been re-opened or built by the end of his tenure, and the process of recovery and rebuilding has continued under his successor Patriarch Kirill. According to official figures, in 2016 the Church had 174 dioceses, 361 bishops, and 34,764 parishes served by 39,800 clergy. There were 926 monasteries and 30 theological schools.[56]

The Russian Church also sought to fill the ideological vacuum left by the collapse of Communism and even, in the opinion of some analysts, became "a separate branch of power".[57]

In August 2000, the ROC adopted its Basis of the Social Concept[58] and in July 2008, its Basic Teaching on Human Dignity, Freedom and Rights.[59]

Under Patriarch Aleksey, there were difficulties in the relationship between the Russian Orthodox Church and the Vatican, especially since 2002, when Pope John Paul II created a Catholic diocesan structure for Russian territory. The leaders of the Russian Church saw this action as a throwback to prior attempts by the Vatican to proselytize the Russian Orthodox faithful to become Roman Catholic. This point of view was based upon the stance of the Russian Orthodox Church (and the Eastern Orthodox Church) that the Church of Rome is in schism, after breaking off from the Orthodox Church. The Roman Catholic Church, on the other hand, while acknowledging the primacy of the Russian Orthodox Church in Russia, believed that the small Roman Catholic minority in Russia, in continuous existence since at least the 18th century, should be served by a fully developed church hierarchy with a presence and status in Russia, just as the Russian Orthodox Church is present in other countries (including constructing a cathedral in Rome, near the Vatican).

There occurred strident conflicts with the Ecumenical Patriarchate, most notably over the Orthodox Church in Estonia in the mid-1990s, which resulted in unilateral suspension of eucharistic relationship between the churches by the ROC.[60] The tension lingered on and could be observed at the meeting in Ravenna in early October 2007 of participants in the Orthodox–Catholic Dialogue: the representative of the Moscow Patriarchate, Bishop Hilarion Alfeyev, walked out of the meeting due to the presence of representatives from the Estonian Apostolic Orthodox Church which is in the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate. At the meeting, prior to the departure of the Russian delegation, there were also substantive disagreements about the wording of a proposed joint statement among the Orthodox representatives.[61] After the departure of the Russian delegation, the remaining Orthodox delegates approved the form which had been advocated by the representatives of the Ecumenical Patriarchate.[62] The Ecumenical See's representative in Ravenna said that Hilarion's position "should be seen as an expression of authoritarianism whose goal is to exhibit the influence of the Moscow Church. But like last year in Belgrade, all Moscow achieved was to isolate itself once more since no other Orthodox Church followed its lead, remaining instead faithful to Constantinople."[63][64]

Canon Michael Bourdeaux, former president of the Keston Institute, said in January 2008 that "the Moscow Patriarchate acts as though it heads a state church, while the few Orthodox clergy who oppose the church-state symbiosis face severe criticism, even loss of livelihood."[65] Such a view is backed up by other observers of Russian political life.[66] Clifford J. Levy of The New York Times wrote in April 2008: "Just as the government has tightened control over political life, so, too, has it intruded in matters of faith. The Kremlin's surrogates in many areas have turned the Russian Orthodox Church into a de facto official religion, warding off other Christian denominations that seem to offer the most significant competition for worshipers. […] This close alliance between the government and the Russian Orthodox Church has become a defining characteristic of Mr. Putin's tenure, a mutually reinforcing choreography that is usually described here as working 'in symphony'."[67]

Throughout Patriarch Alexy's reign, the massive program of costly restoration and reopening of devastated churches and monasteries (as well as the construction of new ones) was criticized for having eclipsed the church's principal mission of evangelizing.[68][69]

On 5 December 2008, the day of Patriarch Alexy's death, the Financial Times said: "While the church had been a force for liberal reform under the Soviet Union, it soon became a center of strength for conservatives and nationalists in the post-communist era. Alexei's death could well result in an even more conservative church."[70]

Under Patriarch Kirill (since 2009)

On 27 January 2009, the ROC Local Council elected Metropolitan Kirill of Smolensk Patriarch of Moscow and All Rus′ by 508 votes out of a total of 700.[71] He was enthroned on 1 February 2009.

Patriarch Kirill implemented reforms in the administrative structure of the Moscow Patriarchate: on 27 July 2011 the Holy Synod established the Central Asian Metropolitan District, reorganizing the structure of the Church in Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan.[72] In addition, on 6 October 2011, at the request of the Patriarch, the Holy Synod introduced the metropoly (Russian: митрополия, mitropoliya), administrative structure bringing together neighboring eparchies.[73]

Under Patriarch Kirill, the ROC continued to maintain close ties with the Kremlin enjoying the patronage of president Vladimir Putin, who has sought to mobilize Russian Orthodoxy both inside and outside Russia.[74] Patriarch Kirill endorsed Putin's election in 2012, referring in February to Putin's tenure in the 2000s as "God′s miracle."[75][76] Nevertheless, Russian inside sources were quoted in the autumn 2017 as saying that Putin's relationship with Patriarch Kirill had been deteriorating since 2014 due to the fact that the presidential administration had been misled by the Moscow Patriarchate as to the extent of support for pro-Russian uprising in eastern Ukraine; also, due to Kirill's personal unpopularity he had come to be viewed as a political liability.[77][78][79]

The Moscow Patriarchate's traditional rivalry with the Patriarchate of Constantinople led to the ROC's non-attendance of the Holy Great Council that had been prepared by all the Orthodox Churches for decades.[80]

The Holy Synod of the ROC, at its session on 15 October 2018, severed full communion with the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople.[81][82] The decision was taken in response to the move made by the Patriarchate of Constantinople a few days prior that effectively ended the Moscow Patriarchate's jurisdiction over Ukraine and promised autocephaly to Ukraine,[83] the ROC's and the Kremlin's fierce opposition notwithstanding.[74][84][85][86] While the Ecumenical Patriarchate finalised the establishment of an autocephalous church in Ukraine on 5 January 2019, the ROC continued to claim that the only legitimate Orthodox jurisdiction in the country was its branch, namely the "Ukrainian Orthodox Church".[87] Under a law of Ukraine adopted at the end of 2018, the latter was required to change its official designation (name) so as to disclose its affiliation with the Russian Orthodox Church based in an "aggressor state".[88][89]

In October 2019, the ROC unilaterally severed communion with the Church of Greece following the latter's recognition of the Ukrainian autocephaly.[90] On 3 November, Patriarch Kirill failed to commemorate the Primate of the Church of Greece, Archbishop Ieronymos II of Athens, during a liturgy in Moscow.[91] Additionally, the ROC leadership imposed pilgrimage bans for its faithful in respect of a number of dioceses in Greece, including that of Athens.[92]

On 8 November 2019, the Russian Orthodox Church announced that Patriarch Kirill would stop commemorating the Patriarch of Alexandria and all Africa after the latter and his Church recognized the OCU that same day.[93][94][95]

Structure and organization

The ROC constituent parts in other than the Russian Federation countries of its exclusive jurisdiction such as Ukraine, Belarus et al., are legally registered as separate legal entities in accordance with the relevant legislation of those independent states.

Ecclesiastiacally, the ROC is organized in a hierarchical structure. The lowest level of organization, which normally would be a single ROC building and its attendees, headed by a priest who acts as Father superior (Russian: настоятель, nastoyatel), constitute a parish (Russian: приход, prihod). All parishes in a geographical region belong to an eparchy (Russian: епархия—equivalent to a Western diocese). Eparchies are governed by bishops (Russian: епископ, episcop or архиерей, archiereus). There are 261 Russian Orthodox eparchies worldwide (June 2012).

Further, some eparchies may be organized into exarchates (currently the Belorussian exarchate), and since 2003 into metropolitan districts (митрополичий округ), such as the ROC eparchies in Kazakhstan and the Central Asia (Среднеазиатский митрополичий округ).

Since the early 1990s, the ROC eparchies in some newly independent states of the former USSR enjoy the status of self-governing Churches within the Moscow Patriarchate (which status, according to the ROC legal terminology, is distinct from the ″autonomous″ one): the Estonian Orthodox Church of Moscow Patriarchate, Latvian Orthodox Church, Moldovan Orthodox Church, Ukrainian Orthodox Church, the last one being virtually fully independent in administrative matters. Similar status, since 2007, is enjoyed by the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (previously fully independent and deemed schismatic by the ROC). The Chinese Orthodox Church and the Japanese Orthodox Churches were granted full autonomy by the Moscow Patriarchate, but this autonomy is not universally recognized.

Smaller eparchies are usually governed by a single bishop. Larger eparchies, exarchates, and self-governing Churches are governed by a Metropolitan archbishop and sometimes also have one or more bishops assigned to them.

The highest level of authority in the ROC is vested in the Local Council (Pomestny Sobor), which comprises all the bishops as well as representatives from the clergy and laypersons. Another organ of power is the Bishops' Council (Архиерейский Собор). In the periods between the Councils the highest administrative powers are exercised by the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church, which includes seven permanent members and is chaired by the Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia, Primate of the Moscow Patriarchate.

Although the Patriarch of Moscow enjoys extensive administrative powers, unlike the Pope, he has no direct canonical jurisdiction outside the diocese of Moscow, nor does he have single-handed authority over matters pertaining to faith as well as issues concerning the entire Orthodox Christian community such as the Catholic-Orthodox split.

Orthodox Church in America (OCA)

Russian traders settled in Alaska during the 18th century. In 1740, a Russian ship off the Alaskan coast recorded celebrating the Divine Liturgy. In 1794, the Russian Orthodox Church sent missionaries—among them Herman of Alaska (who was later canonized)—to establish a formal mission in Alaska. Their missionary endeavors contributed to the conversion of many Alaskan natives to the Orthodox faith, especially after they learned the local languages and began to translate the liturgy into these. The ROC established a diocese, whose first bishop was Innocent of Alaska (also later canonized). Around the mid-19th century, the ROC moved this headquarters of the North American Diocese from Alaska to northern California.

Following additional changes in population, the headquarters of the North American Diocese was moved in the late 19th century from California to New York City, which had become a destination of numerous Greek and other Orthodox immigrants. At this time, many Greek Catholics shifted into the Orthodox Church in the East of the United States, increasing the numbers of Orthodox Christians in America.

There had been a conflict between John Ireland, the politically powerful Roman Catholic Archbishop of Saint Paul, Minnesota; and Alexis Toth, an influential Ruthenian Catholic priest of St. Mary's church in Minneapolis. Because Archbishop Ireland refused to accept Fr. Toth's credentials as a priest, Fr Toth converted his parish of St. Mary's to the Orthodox Church. Under his guidance and inspiration, tens of thousands of other Greek Catholics in North America converted to the Orthodox Church. Ireland is sometimes honored as the "Father of the Orthodox Church in America". Such Greek Catholics were received into Orthodoxy into the existing North American diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church.

At the same time large numbers of Greek and other Orthodox Christians were also immigrating to America. All Orthodox Christians in North America were united under the omophorion (church authority and protection) of the Patriarch of Moscow, through the Russian Church's North American diocese. There was then no other Orthodox diocese on the continent. A Syro-Arab mission was established under the episcopal leadership of Fr. Raphael of Brooklyn (later canonized in the church), who was the first Orthodox bishop to be consecrated in the United States.

In 1920, after the Russian Revolution and establishment of the Soviet Union, Patriarch Tikhon of Moscow issued an ukase (decree) that dioceses of the Church of Russia that were cut off from the governance of the highest Church authority should be managed independently until such time as normal relations could be resumed. Accordingly, the North American diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church (known as the "Metropolia") operated in a de facto autonomous mode of self-governance. The Russian Revolution resulted in financial hardship for the North American diocese, as well as for the church in the Soviet Union. Other national Orthodox communities in North America tended to turn to the churches in their respective homelands for pastoral care and governance.

A group of bishops who had left Russia as refugees in the wake of the Russian Civil War, gathered in Sremski-Karlovci. This was traditionally known as the seat of Serbian Orthodox Church under the Habsburg Monarchy. In 1918, following the Great War, this city became part of the Kingdom of Serbia and, subsequently that year, of the new Yugoslavia. The bishops adopted a pro-monarchist stand. They claimed to speak as a synod for the entire "free" Russian church. This group was formally dissolved in 1922 by Patriarch Tikhon. He appointed metropolitans Platon and Evlogy as ruling bishops in the United States and Europe, respectively. Both of these metropolitans continued to entertain relations intermittently with the synod in Karlovci. Many of the Russian emigrants ignored Patriarch Tikhon's attempts to control the church outside Russia, believing that he was too subservient to the Soviets.

Between the world wars, the Metropolia coexisted and at times cooperated with an independent synod, later known as the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (ROCOR), sometimes called the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad. The two groups eventually operated independently. After World War II, ROCOR moved its headquarters to North America, following renewed Russian immigration especially to the United States. It claimed but failed to establish jurisdiction over all parishes of Russian origin in North America. The Metropolia, as a former diocese of the Russian Church, continued to consider the latter as its highest church authority, although it was cut off under the conditions of the Communist regime in Russia.

After World War II, the Patriarchate of Moscow made unsuccessful attempts to regain control over the groups abroad. After resuming communication with Moscow in early 1960s, and being granted autocephaly in 1970, the Metropolia became known as the Orthodox Church in America.[96][97] But such recognition of its autocephalous status is not universal. The Ecumenical Patriarch (under whom is the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America) and some other jurisdictions have not officially accepted it. The Ecumenical Patriarch and the other jurisdictions remain in communion with the OCA. The Patriarchate of Moscow thereby renounced its former canonical claims in the United States and Canada; it acknowledged an autonomous church also established in Japan in 1970.

Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (ROCOR)

Russia's Church was devastated by the repercussions of the Bolshevik Revolution. One of its effects was a flood of refugees from Russia to the United States, Canada, and Europe. The Revolution of 1918 severed large sections of the Russian church—dioceses in America, Japan, and Manchuria, as well as refugees in Europe—from regular contacts with the main church.

Based on an ukase (decree) issued by Patriarch Tikhon, Holy Synod and Supreme Council of the Church stated that dioceses of the Church of Russia that were cut off from the governance of the highest Church authority (i.e. the Holy Synod and the Patriarch) should be managed independently until such time as normal relations with the highest Church authority could be resumed, the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia was established; by bishops who had left Russia in the wake of the Russian Civil War. They first met in Constantinople, and then moved to Sremski-Karlovci, Yugoslavia. After World War II, they moved their headquarters to Munich, and 1950 to New York City, New York, where it remains to this day.

On 28 December 2006, it was officially announced that the Act of Canonical Communion would finally be signed between the ROC and ROCOR. The signing took place on 17 May 2007, followed immediately by a full restoration of communion with the Moscow Patriarchate, celebrated by a Divine Liturgy at the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, at which the Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia Alexius II and the First Hierarch of ROCOR concelebrated for the first time.

Under the Act, the ROCOR remains a self-governing entity within the Church of Russia. It is independent in its administrative, pastoral, and property matters. It continues to be governed by its Council of Bishops and its Synod, the Council's permanent executive body. The First-Hierarch and bishops of the ROCOR are elected by its Council and confirmed by the Patriarch of Moscow. ROCOR bishops participate in the Council of Bishops of the entire Russian Church.

In response to the signing of the act of canonical communion, Bishop Agathangel (Pashkovsky) of Odessa and parishes and clergy in opposition to the Act broke communion with ROCOR, and established ROCA(A)[98] Some others opposed to the Act have joined themselves to other Greek Old Calendarist groups.[99]

Currently both the OCA and ROCOR, since 2007, are in communion with the ROC.

Self-governing branches of the ROC

The Russian Orthodox Church has four levels of self-government.[100][101]

- Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate), a special status autonomy close to autocephaly

- Self-governed churches (Estonia, Latvia, Moldova)

- Belarusian Orthodox Church

- Metropolitan Districts of Kazakhstan

- Japanese Orthodox Church

- Chinese Orthodox Church

Worship and practices

Canonization

In accordance with the practice of the Orthodox Church, a particular hero of faith can initially be canonized only at a local level within local churches and eparchies. Such rights belong to the ruling hierarch and it can only happen when the blessing of the patriarch is received. The task of believers of the local eparchy is to record descriptions of miracles, to create the hagiography of a saint, to paint an icon, as well as to compose a liturgical text of a service where the saint is canonized. All of this is sent to the Synodal Commission for canonization which decides whether to canonize the local hero of faith or not. Then the patriarch gives his blessing and the local hierarch performs the act of canonization at the local level. However, the liturgical texts in honor of a saint are not published in all Church books but only in local publications. In the same way these saints are not yet canonized and venerated by the whole Church, only locally. When the glorification of a saint exceeds the limits of an eparchy, then the patriarch and Holy Synod decides about their canonization on the Church level. After receiving the Synod's support and the patriarch's blessing, the question of glorification of a particular saint on the scale of the entire Church is given for consideration to the Local Council of the Russian Orthodox Church.

In the period following the revolution, and during the communist persecutions up to 1970, no canonizations took place. Only in 1970 did the Holy Synod made a decision to canonize a missionary to Japan, Nicholas Kasatkin (1836–1912). In 1977, St. Innocent of Moscow (1797–1879), the Metropolitan of Siberia, the Far East, the Aleutian Islands, Alaska, and Moscow was also canonized. In 1978 it was proclaimed that the Russian Orthodox Church had created a prayer order for Meletius of Kharkov, which practically signified his canonization because that was the only possible way to do it at that time. Similarly, the saints of other Orthodox Churches were added to the Church calendar: in 1962 St. John the Russian, in 1970 St. Herman of Alaska, in 1993 Silouan the Athonite, the elder of Mount Athos, already canonized in 1987 by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. In the 1980s the Russian Orthodox Church re-established the process for canonization; a practice that had ceased for half a century.

In 1989, the Holy Synod established the Synodal Commission for canonization. The 1990 Local Council of the Russian Orthodox Church gave an order for the Synodal Commission for Canonisation to prepare documents for canonization of new martyrs who had suffered from the 20th century Communist repressions. In 1991 it was decided that a local commission for canonization would be established in every eparchy which would gather the local documents and would send them to the Synodal Commission. Its task was to study the local archives, collect memories of believers, record all the miracles that are connected with addressing the martyrs. In 1992 the Church established 25 January as a day when it venerates the new 20th century martyrs of faith. The day was specifically chosen because on this day in 1918 the Metropolitan of Kiev Vladimir (Bogoyavlensky) was killed, thus becoming the first victim of communist terror among the hierarchs of the Church.

During the 2000 Council of the Russian Orthodox Church, the greatest general canonization in the history of the Orthodox Church took place: not only regarding the number of saints but also as in this canonization, all unknown saints were mentioned. There were 1,765 canonized saints known by name and others unknown by name but "known to God".

Icon painting

The use and making of icons entered Kievan Rus' following its conversion to Orthodox Christianity in AD 988. As a general rule, these icons strictly followed models and formulas hallowed by Byzantine art, led from the capital in Constantinople. As time passed, the Russians widened the vocabulary of types and styles far beyond anything found elsewhere in the Orthodox world. Russian icons are typically paintings on wood, often small, though some in churches and monasteries may be much larger. Some Russian icons were made of copper.[102] Many religious homes in Russia have icons hanging on the wall in the krasny ugol, the "red" or "beautiful" corner. There is a rich history and elaborate religious symbolism associated with icons. In Russian churches, the nave is typically separated from the sanctuary by an iconostasis (Russian ikonostas, иконостас), or icon-screen, a wall of icons with double doors in the centre. Russians sometimes speak of an icon as having been "written", because in the Russian language (like Greek, but unlike English) the same word (pisat', писать in Russian) means both to paint and to write. Icons are considered to be the Gospel in paint, and therefore careful attention is paid to ensure that the Gospel is faithfully and accurately conveyed. Icons considered miraculous were said to "appear." The "appearance" (Russian: yavlenie, явление) of an icon is its supposedly miraculous discovery. "A true icon is one that has 'appeared', a gift from above, one opening the way to the Prototype and able to perform miracles".[103]

Bell ringing

Bell ringing, which has a history in the Russian Orthodox tradition dating back to the baptism of Rus', plays an important part in the traditions of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Ecumenism and interfaith relations

In May 2011, Hilarion Alfeyev, the Metropolitan of Volokolamsk and head of external relations for the Moscow Patriarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church, stated that Orthodox and Evangelical Christians share the same positions on "such issues as abortion, the family, and marriage" and desire "vigorous grassroots engagement" between the two Christian communions on such issues.[104]

The Metropolitan also believes in the possibility of peaceful coexistence between Islam and Christianity because the two religions have never fought religious wars in Russia.[105] Alfeyev stated that the Russian Orthodox Church "disagrees with atheist secularism in some areas very strongly" and "believes that it destroys something very essential about human life."[105]

Today the Russian Orthodox Church has ecclesiastical missions in Jerusalem and some other countries around the world.[106][107]

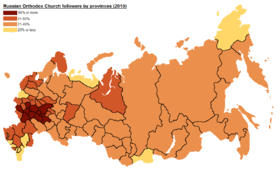

Membership

The ROC is often said[108] to be the largest of the Eastern Orthodox churches in the world. Including all the autocephalous churches under its supervision, its adherents number more than 112 million worldwide—about half of the 200 to 230 million[109][9] estimated adherents of the Eastern Orthodox Church. Among Christian churches, the Russian Orthodox Church is second only to the Roman Catholic Church in terms of numbers of followers. Within Russia the results of a 2007 VTsIOM poll indicated that about 75% of the population considered themselves Orthodox Christians.[110] Up to 65% of ethnic Russians[111][112] as well as Russian-speakers belonging to other ethnic groups from Russia (Ossetians, Caucasus Greeks etc.) and a similar percentage of Belarusians and Ukrainians identify themselves as "Orthodox".[110][111][113] However, according to a poll published by the church related website Pravmir.com in December 2012, only 41% of the Russian population identified itself with the Russian Orthodox Church.[114] Pravmir.com also published a 2012 poll by the respected Levada organization VTsIOM indicating that 74% of Russians considered themselves Orthodox.[115]

See also

- Eparchies of the Russian Orthodox Church

Notes

References

Citations

- "Внутренняя жизнь и внешняя деятельность Русской Православной Церкви с 2009 года по 2019 год". Патриархия.ru.

- Доклад Святейшего Патриарха Кирилла на Епархиальном собрании г. Москвы (20 декабря 2019 года)

- Russian Orthodox Church at World Council of Churches

- "Vladimir I – Russiapedia History and mythology Prominent Russians". Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Voronov, Theodore (13 October 2001). "The Baptism of Russia and Its Significance for Today". orthodox.clara.net. Archived from the original on 18 April 2007. Retrieved 12 July 2007.

- Damick, Andrew S. "Life of the Apostle Andrew". chrysostom.org. Archived from the original on 27 July 2007. Retrieved 12 July 2007.

- Voronov, Theodore (13 October 2001). "The Baptism of Ukraine and Its Significance for Today". orthodox.clara.net. Archived from the original on 18 April 2007. Retrieved 12 July 2007.

- "Primacy and Synodality from an Orthodox Perspective". Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- "Orthodox Christianity in the 21st Century". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 8 November 2017.

- "Religions in Russia: a New Framework". www.pravmir.com.

- "Number of Orthodox Church Members Shrinking in Russia, Islam on the Rise - Poll". www.pravmir.com.

- "Russian Orthodox Church | History & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Brien, Joanne O.; Palmer, Martin (2007). The Atlas of Religion. Univ of California Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-520-24917-2.

- "I. Общие положения – Русская православная Церковь". Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- "Диптих". Archived from the original on 28 October 2012. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Damick, Andrew S. "Life of the Apostle Andrew". Chrysostom. Archived from the original on 27 July 2007. Retrieved 25 June 2007.

- Voronov, Theodore (13 October 2001). "The Baptism of Russia and Its Significance for Today". Orthodox. Clara. Archived from the original on 18 April 2007. Retrieved 25 June 2007.

- "ИОНА". Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Karl August von Hase. A history of the Christian Church. Oxford, 1855. p. 481.

- Lindsey Hughes, Russia in the Age of Peter the Great (1998) pp. 332–56.

- Yuri Kagramanov, "The war of languages in Ukraine Archived 1 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine", Novy Mir, 2006, № 8

- РПЦ: вмешательство Константинополя в ситуацию на Украине может породить новые расколы: Митрополит Волоколамский Иларион завил, что Русская православная церковь представит доказательства неправомерности притязаний Константинополя на Украину TASS, 1 September 2018.

- Ecumenical Patriarch Takes Moscow Down a Peg Over Church Relations with Ukraine orthodoxyindialogue.com, 2 July 2018.

- Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew: “As the Mother Church, it is reasonable to desire the restoration of unity for the divided ecclesiastical body in Ukraine” (The Homily by Patriarch Bartholomew after the memorial service for the late Metropolitan of Perge, Evangelos) The official website of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, 2 July 2018.

- Константин Ветошников. «Передача» Киевской митрополии Московскому патриархату в 1686 году: канонический анализ risu.org.ua, 25 December 2016.

- A. S. Pankratov, Ishchushchie boga (Moscow, 1911); Vera Shevzov, Russian Orthodoxy on the Eve of Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004); Gregory Freeze, 'Subversive Piety: Religion and the Political Crisis in Late Imperial Russia', Journal of Modern History, vol. 68 (June 1996): 308–50; Mark Steinberg and Heather Coleman, eds. Sacred Stories: Religion and Spirituality in Modern Russia (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2007)

- "What role did the Orthodox Church play in the Reformation in the 16th Century?". Living the Orthodox Life. Archived from the original on 29 August 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- Palmieri, F. Aurelio. “The Church and the Russian Revolution,” Part II, The Catholic World, Vol. CV, N°. 629, August 1917.

- "Анафема св. патриарха Тихона против советской власти и призыв встать на борьбу за веру Христову". Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Ostling, Richard (24 June 2001). "Cross meets Kremlin". TIME Magazine.

- Father Arseny 1893–1973 Priest, Prisoner, Spiritual Father. Introduction pp. vi–1. St Vladimir's Seminary Press ISBN 0-88141-180-9

- Sullivan, Patricia (26 November 2006). "Anti-Communist Priest Gheorghe Calciu-Dumitreasa". The Washington Post. p. C09.

- John Shelton Curtis, The Russian Church and the Soviet State (Boston: Little Brown, 1953); Jane Ellis, The Russian Orthodox Church: A Contemporary History (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986); Dimitry V. Pospielovsky, The Russian Church Under the Soviet Regime 1917–1982 (St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1984); idem., A History of Marxist-Leninist Atheism and Soviet Anti-Religious Policies (New York; St. Martin's Press, 1987); Glennys Young, Power and the Sacred in Revolutionary Russia: Religious Activists in the Village (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997); Daniel Peris, Storming the Heavens: The Soviet League of the Militant Godless (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1998); William B. Husband, "Godless Communists": Atheism and Society in Soviet Russia (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2000; Edward Roslof, Red Priests: Renovationism, Russian Orthodoxy, and Revolution, 1905–1946 (Bloomington, Indiana, 2002)

- (in Russian) Alekseev, Valery. Historical and canonical reference for reasons making believers leave the Moscow patriarchate. Created for the government of Moldova Archived 29 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Talantov, Boris. 1968. The Moscow Patriarchate and Sergianism (English translation).

- Protopriest Yaroslav Belikow. 11 December 2004. The Visit of His Eminence Metropolitan Laurus to the Parishes of Argentina and Venezuela Archived 29 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine."

- Tserkovnye Vedomosti Russkoy Istinno-Pravoslavnoy Tserkvi (Russian True Orthodox Church News). Patriarch Tikhon's Catacomb Church. History of the Russian True Orthodox Church.

- Fitzpatrick, Sheila. 1999. Everyday Stalinism: Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times: Soviet Russia in the 1930s. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 179-82.

- "Московський патріархат створювали агенти НКВС, – свідчать розсекречені СБУ документи". espreso.tv.

- СБУ рассекретила архивы: московского патриарха в 1945 году избирали агенты НКГБ

- Sally, Waller. Tsarist and Communist Russia 1855–1964 (Second ed.). Oxford. ISBN 9780198354673. OCLC 913789474.

- "Dissent in the Russian Orthodox Church," Russian Review, Vol. 28, N 4, October 1969, pp. 416–27.

- "Father Dmitri Dudko". The Independent Obituaries

- Keston Institute and the Defence of Persecuted Christians in the USSR

- Born Again. Putin and Orthodox Church Cement Power in Russia. by Andrew Higgins, Wall Street Journal, 18 December 2007.

- Выписки из отчетов КГБ о работе с лидерами Московской патриархии Archived 8 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine Excerpts from KGB reports on work with the leaders of the Moscow Patriarchate

- Russian Patriarch 'was KGB spy' The Guardian, 12 February 1999

- Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin, The Mitrokhin Archive: The KGB in Europe and the West, Gardners Books (2000), ISBN 0-14-028487-7

- Yevgenia Albats and Catherine A. Fitzpatrick. The State Within a State: The KGB and Its Hold on Russia – Past, Present, and Future. 1994. ISBN 0-374-52738-5, p. 46.

- Konstantin Preobrazhenskiy – Putin's Espionage Church Archived 9 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, an excerpt from a forthcoming book, "Russian Americans: A New KGB Asset" by Konstantin Preobrazhenskiy

- Confirmed: Russian Patriarch Worked with KGB, Catholic World News. Retrieved 29 December 2007.

- George Trofimoff Affidavit Archived 27 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Ириней (Зуземиль) Archived 9 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine Biography information on the web-site of the ROC

- Nathaniel Davis, A Long Walk to Church: A Contemporary History of Russian Orthodoxy, (Oxford: Westview Press, 1995), p. 96 Davis quotes one bishop as saying: "Yes, we—I, at least, and I say this first about myself—I worked together with the KGB. I cooperated, I made signed statements, I had regular meetings, I made reports. I was given a pseudonym—a code name as they say there. ... I knowingly cooperated with them—but in such a way that I undeviatingly tried to maintain the position of my Church, and, yes, also to act as a patriot, insofar as I understood, in collaboration with these organs. I was never a stool pigeon, nor an informer."

- He said: "Defending one thing, it was necessary to give somewhere else. Were there any other organizations, or any other people among those who had to carry responsibility not only for themselves but for thousands of other fates, who in those years in the Soviet Union were not compelled to act likewise? Before those people, however, to whom the compromises, silence, forced passivity or expressions of loyalty permitted by the leaders of the church in those years caused pain, before these people, and not only before God, I ask forgiveness, understanding and prayers." From an interview of Patriarch Alexy II, given to Izvestia No 137, 10 June 1991, entitled "Patriarch Alexy II: – I Take upon Myself Responsibility for All that Happened", English translation from Nathaniel Davis, A Long Walk to Church: A Contemporary History of Russian Orthodoxy (Oxford: Westview Press, 1995), p. 89. See also History of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad Archived 13 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine, by St. John (Maximovich) of Shanghai and San Francisco, 31 December 2007

- Русская церковь объединяет свыше 150 млн. верующих в более чем 60 странах – митрополит Иларион Interfax.ru 2 March 2011

- Charles Clover (5 December 2008). "Russia's church mourns patriarch". Financial Times. London. Archived from the original on 29 March 2010. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

- "The Basis of the Social Concept". Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- "The Russian Orthodox Church's Basic Teaching on Human Dignity, Freedom and Rights". Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Телеграмма Патриаха Алексия Патриаху Константинопольскому Варфоломею I от 23 февраля 1996 // ЖМП 1996, № 3 (Официальная часть).

- "No 130 (October 21, 2007) » Europaica Bulletin » OrthodoxEurope.org". Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- "Interfax-Religion". Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Progress in dialogue with Catholics, says Ecumenical Patriarchate new.asianews.it 19 October 2007. Archived 26 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Ecumenical progress, Russian isolation, after Catholic-Orthodox talks CWNews.com 19 October 2007.

- President Putin and the patriarchs. by Michael Bourdeaux, The Times, 11 January 2008.

- Piety's Comeback as a Kremlin Virtue. Archived 11 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Alexander Osipovich, The Moscow Times, 12 February 2008. p. 1.

- Clifford J. Levy. "At Expense of All Others, Putin Picks a Church." The New York Times. 24 April 2008.

- Патриарх Алексий Второй: эпоха упущенных возможностей RISU 11 December 2008

- Ветряные мельницы православия Vlast 15 December 2008.

- Clover, Charles (5 December 2008). "Russia's church mourns patriarch". The Financial Times. Archived from the original on 29 March 2010. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

- Незнакомый патриарх, или Чему нас учит история храма Христа Спасителя Izvestia 26 January 2009. Archived 1 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Решением Священного Синода образован Среднеазиатский митрополичий округ

- ЖУРНАЛЫ заседания Священного Синода от 5–6 октября 2011 года

- Tisdall, Simon (14 October 2018). "Archbishop's defiance threatens Putin's vision of Russian greatness". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- Стенограмма встречи председателя Правительства РФ В.В. Путина со Святейшим Патриархом Кириллом и лидерами традиционных религиозных общин России patriarchia.ru, 6 February 2012.

- Julia Gerlach and Jochen Töpfer, eds. (2014). The Role of Religion in Eastern Europe Today. Springer. p. 135. ISBN 978-3658024413.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Почему испортились отношения патриарха Кирилла с Путиным religiopolis.org, 30 October 2017.

- Борьба башен или неумеренный аппетит? Почему Путин избегает патриарха sobesednik.ru, 23 October 2017.

- Из-за чего Путин сторонится патриарха: «Собеседник» узнал, за что Кирилл попал в опалу

- Chichowlas, Ola (30 June 2016). "Ukrainian Question Divides Orthodox World". The Moscow Times. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- Священный Синод Русской Православной Церкви признал невозможным дальнейшее пребывание в евхаристическом общении с Константинопольским Патриархатом patriarchia.ru, 15 October 2018.

- ЖУРНАЛЫ заседания Священного Синода Русской Православной Церкви от 15 октября 2018 года patriarchia.ru, 15 October 2018.

- Announcement (11/10/2018). patriarchate.org, 11 October 2018.

- "Putin Is the Biggest Loser of Orthodox Schism".

- "Russian Orthodox Church Breaks Ties With Constantinople Patriarchate". RFERL. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- "Russian Church breaks with Orthodox body". BBC News. 16 October 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- Журналы заседания Священного Синода от 28 декабря 2018 года. Журнал № 98. patriarchia.ru, 28 December 2018.

- "Ukraine's President Signs Law Forcing Russia-Affiliated Church To Change Name". Radio Liberty. 22 December 2018.

- "Poroshenko signs law on Ukrainian Orthodox Church renaming". TASS. 22 December 2018.

- "Заявление Священного Синода Русской Православной Церкви". Department of External Church Affairs of the Moscow Patriarchate. 17 October 2019.

- "Патриарх Кирилл впервые не помянул главу Элладской церкви в богослужении: Священный синод РПЦ ранее постановил прекратить молитвенное общение с иерархами ЭПЦ". TASS (in Russian). 3 November 2018.

- "Church of Greece calmly monitors the actions of Moscow". Orthodox Times. 4 November 2019.

- "Patriarch Kirill to cease liturgical commemoration of Patriarch of Alexandria - Moscow Patriarchate spokesman". www.interfax-religion.com. 8 November 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- "РПЦ считает невозможным дальнейшее поминовение Александрийского патриарха". www.interfax-religion.ru (in Russian). 8 November 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- "Patriarchate of Alexandria recognizes Autocephalous Church of Ukraine (upd)". Orthodox Times. 8 November 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- Very Rev. John Matusiak, Director of Communications, Orthodox Church in America. "A History and Introduction of the Orthodox Church in America"

- OrthodoxWiki. ROCOR and OCA Archived 6 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Russian Orthodox Church Abroad (ROCA), Synod of Bishops". Sinod.ruschurchabroad.org. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- "The Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia – Official Website". Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Belarusian Orthodox Church wants autonomy from Moscow. Ukrayinska Pravda. 19 December 2014

- "Belarusian Orthodox Church Seeks More Independence from Russia". Belarus Digest: News and analytics on Belarusian politics, economy, human rights and more. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- Ahlborn, Richard E. and Vera Beaver-Bricken Espinola, eds. Russian Copper Icons and Crosses From the Kunz Collection: Castings of Faith. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. 1991. 85 pages with illustrations, some colored. Includes bibliographical references pp. 84–85. Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology: No. 51.

- Father Vladimir Ivanov (1988). Russian Icons. Rizzoli Publications.

- "From Russia, with Love". Christianity Today. Retrieved 31 December 2007.

Many evangelicals share conservative positions with us on such issues as abortion, the family, and marriage. Do you want vigorous grassroots engagement between Orthodox and evangelicals? Yes, on problems, for example, like the destruction of the family. Many marriages are split. Many families have either one child or no child.

- "From Russia, with Love". Christianity Today. Retrieved 31 December 2007.

If we speak about Islam (and of course if we mean moderate Islam), then I believe there is the possibility of peaceful coexistence between Islam and Christianity. This is what we have had in Russia for centuries, because Russian Islam has a very long tradition. But we never had religious wars. Nowadays we have a good system of collaboration between Christian denominations and Islam. Secularism is dangerous because it destroys human life. It destroys essential notions related to human life, such as the family. And here we disagree with atheist secularism in some areas very strongly, and we believe that it destroys something very essential about human life. We should be engaged in a very honest and direct conversation with representatives of secular ideology. And of course when I speak of secular ideology, I mean here primarily atheist ideology.

- "Russian Orthodox Mission in Haiti – Home". Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- "The Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia – Official Website". Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Because the ROC does not keep any formal membership records the claim is based on public polls and the number of parishes. The actual number of regular church-goers in Russia varies between 1% and 10%, depending on the source. However, strict adherence to Sunday church-going is not traditional in Eastern Orthodoxy, specifically in Russia.

- "BBC - Religions - Christianity: Eastern Orthodox Church". www.bbc.co.uk.

- Русская церковь объединяет свыше 150 млн. верующих в более чем 60 странах – митрополит Иларион Interfax.ru 2 March 2011

- Опубликована подробная сравнительная статистика религиозности в России и Польше Religare.ru 6 June 2007

- Большинство, напоминающее меньшинство Gazeta.ru 21 August 2007

- "Russian Orthodox Church denies plans to create private army". RIA Novosti. BBC News. 21 November 2008. Retrieved 13 December 2008.