Urfa

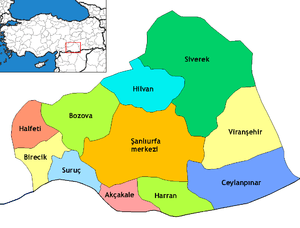

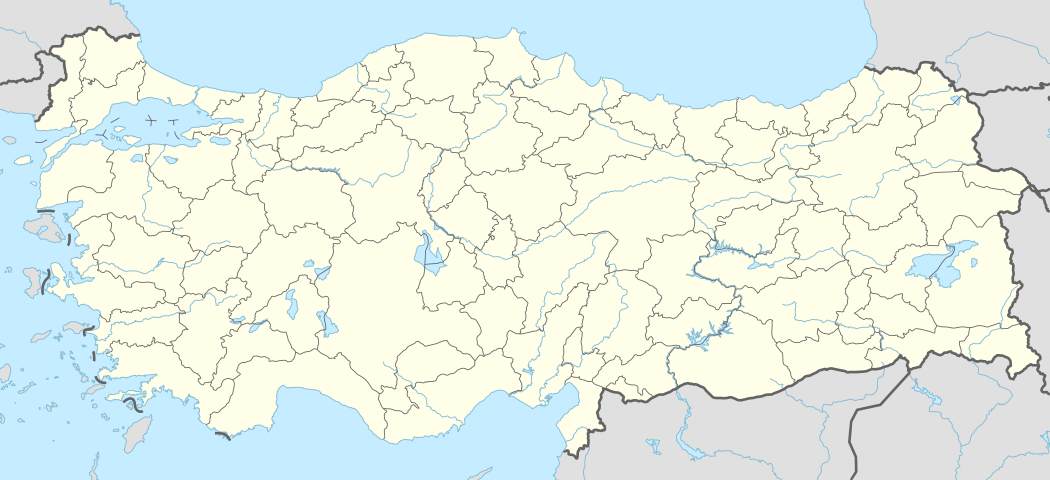

Urfa, officially known as Şanlıurfa (pronounced [ʃanˈɫɯuɾfa]; Arabic: al-Ruha; Kurdish: Riha[2]; Armenian: Ուռհա, romanized: Uṙha; Syriac: ܐܘܪܗܝ, romanized: Ūrhāi and known in ancient times as Edessa, is a city with a population of over 2 million residents[3] in south-eastern Turkey, and the capital of Şanlıurfa Province. Urfa is a multiethnic city with a Turkish, Kurdish and Arab population. Urfa is situated on a plain about eighty kilometres east of the Euphrates River. Its climate features extremely hot, dry summers and cool, moist winters.

Urfa | |

|---|---|

| Şanlıurfa | |

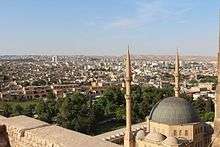

Urfa skyline | |

Urfa  Urfa | |

| Coordinates: 37°09′30″N 38°47′30″E | |

| Country | Turkey |

| Province | Şanlıurfa |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Zeynel Abidin Beyazgül (AKP) |

| • Governor | Abdullah Erin |

| Area | |

| • District | 3,668.76 km2 (1,416.52 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 477 m (1,565 ft) |

| Population (2018) | |

| • Total | 2,031,425 |

| Website | https://www.sanliurfa.bel.tr |

Name

For a while during the rule of Antiochus IV Epiphanes (175 - 164 BCE) the city was named Callirrhoe or Antiochia on the Callirhoe (Ancient Greek: Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Καλλιρρόης). During Byzantine rule it was named Justinopolis. Prior to Turkish rule, it was often best known by the name given it by the Seleucids, Ἔδεσσα, Édessa.

Şanlı means "great, glorious, dignified" in Turkish, and Urfa was officially renamed Şanlıurfa ("Urfa the Glorious") by the Turkish Grand National Assembly in 1984, in recognition of the local resistance in the Turkish War of Independence. The title was achieved following repeated requests by the city's members of parliament, desirous to earn a title similar to those of neighbouring cities Gazi (veteran) Antep and Kahraman (Heroic) Maraş.

History

.jpg)

The history of Urfa is recorded from the 4th century BC, but may date back at least to 9000 BC, when there is ample evidence for the surrounding sites at Duru, Harran and Nevali Cori.[5]

Neolithic

Urfa is one of the truly ancient cities of the world. In shares the Balikh River Valley region with two other signifigant Neolithic sites at Nevalı Çori and Göbekli Tepe. The city began circa 9000 BCE as a PPNA Neolithic site located near Abrahams Pool (Site Name: Balıklıgöl). It was part of a network of first settlements spanning West Asia where agriculture began. It was here that the life-sized limestone "Urfa Man" statue was found during an excavation and is now on display at the Şanlıurfa Archaeology and Mosaic Museum.[6] The Urfa Man resembles both carvings at nearby Gobekli Tepe and statues found at 'Ain Ghazal. The village at Balıklıgöl was followed by a string of four PPNB villages on four hilltops at the Gürcütepe site. Beginning in 6200 BCE small Halaf culture villages began to appear in the Balikh Valley. The typical Halaf village is 2ha with a population of 500 people surrounded by agricultural fields. By 5000 BCE the entire valley was densely filled. Two of the these villages would become the nuclei for the major cities of Urfa and Harran.

Bronze Age

The Uruk period expansion triggered the formation of cities on the upper Euphrates. in a process known as secondary urbanization the countryside villages emptied out and was replaced by a city. this process began in about 3200 BC. The rise of Urfa and Harran mirror the rise of Ebla as all three were driven by the same underlying economic expansion of Uruk. By the Early Bronze Age (2900-2600 BCE) Urfa had grown into a walled city of 200ha. This city is located at the archeological site Kazane Tepe adjacent to modern Urfa. There is a tentative, yet unproven identification of ancient Urfa (Kazane Tepe) with the city of Urshu. Urshu is mentioned in the Ebla archives as an kingdom joined in political alliance with Ebla by marrige through a princess of the royal house. Ancient Urfa continued as an soverign bronze age city-state until its annexation into the Akkadian Empire and its successor the Neo-Sumerian Empire. After the fall of Ur it was again independant for a time until it was abandoned in the Amorite expansion in 1800 BCE.

Biblical History

According to Jewish and Muslim sources, Urfa is Ur Kasdim, the hometown of Abraham, the grandfather of Jacob whom God named Israel. This identification was disputed by Leonard Woolley, the excavator of the Sumerian city of Ur in 1927 and scholars remain divided on the issue. Urfa is also one of several cities that have traditions associated with Job.

Aremenian History

For the Armenians, Urfa is considered a holy place since it is believed that the Armenian alphabet was invented there.[7]

Urfa was conquered repeatedly throughout history, and has been dominated by many civilizations, including the Ebla, Akkadians, Sumerians, Babylonians, Hittites, Hurri-Mitannis, Assyrians, Medes, Persians, Ancient Macedonians (under Alexander the Great), Seleucids, Armenians, Arameans, the Neo-Assyrian Osrhoenes, Romans, Sassanids, Byzantines, and Arabs

City of Edessa

Although the site of Urfa has been inhabited since prehistoric times, the modern city was founded in 304 B.C by Seleucus I Nicator and named after the ancient capital of Macedonia. In the late 2nd century, as the Seleucid dynasty disintegrated, it became the capital of the Arab Nabataean Abgar dynasty, which was successively a Parthian, Armenian, and Roman client state and eventually a Roman province. Its location on the eastern frontier of the Empire meant it was frequently conquered during periods when the Byzantine central government was weak, and for centuries, it was alternately conquered by Arab, Byzantine, Armenian, Turkish rulers. In 1098, the Crusader Baldwin of Boulogne induced the final Armenian ruler to adopt him and then seized power, establishing the first Crusader State known as the County of Edessa and imposing Latin Christianity on the Greek Orthodox and Armenian Apostolic majority of the population.

Age of Islam

Islam first arrived in Urfa around 638 AD, when the region surrendered to the Rashidun army without resisting, and became a significant presence under the Ayyubids (see: Saladin Ayubbi), Seljuks. In 1144, the Crusader state fell to the Turkish Abassid general Zengui, who had most of the Christian inhabitants slaughtered together with the Latin archbishop (see Siege of Edessa) and the subsequent Second Crusade failed to recapture the city.[8] Subsequently, Urfa was ruled by Zengids, Ayyubids, Sultanate of Rum, Ilkhanids, Memluks, Akkoyunlu and Safavids before Ottoman conquest in 1516.

Under the Ottomans Urfa was initially made centre of Raqqa Eyalet, laterly part Urfa (Sanjak) of the Aleppo Vilayet. The area became a centre of trade in cotton, leather, and jewellery. There was a small but ancient Jewish community in Urfa,[9] with a population of about 1,000 by the 19th century.[10] Most of the Jews emigrated in 1896, fleeing the Hamidian massacres, and settling mainly in Aleppo, Tiberias and Jerusalem. There were three Christian communities: Syriac, Armenian, and Latin. According to Lord Kinross,[11] 8,000 Armenians were massacred in Urfa in 1895. The last Neo-Aramaic Christians left in 1924 and went to Aleppo (where they settled in a place that was later called Hay al-Suryan "The Syriac Quarter").[12]

First World War and after

During the First World War, Urfa was a site of the Armenian and Assyrian Genocides, beginning in August 1915.[13] By the end of the war, the entire Christian population had been killed, had fled, or was in hiding.

The British occupation of the city of Urfa started de facto on 7 March 1919 and officially de jure as of 24 March 1919, and lasted until 30 October 1919. French forces took over the next day and lasted until 11 April 1920, when they were defeated by local resistance forces before the formal declaration of the Republic of Turkey on 23 April 1920).

The French retreat from the city of Urfa was conducted under an agreement reached between the occupying forces and the representatives of the local forces, commanded by Captain Ali Saip Bey assigned from Ankara. The withdrawal was meant to take place peacefully, but was disrupted by an ambush on the French units by irregular Kuva-yi Milliye Şebeke Pass on the way to Syria, leading to 296 casualties among the French.

Modern Urfa presents stark contrasts between its old and new quarters.

Politics

It is a stronghold of the governing Justice and Development Party. However, in the 2009 local elections, the city elected an independent, Ahmet Eşref Fakibaba, as mayor.[14]

Cuisine

As the city of Urfa is deeply rooted in history, so its unique cuisine is an amalgamation of the cuisines of the many civilizations that have ruled in Urfa . Dishes carry names in Kurdish, Arabic, Armenian, Syriac, and Turkish, and are often prepared in a spicy manner. It is widely believed that Urfa is the birthplace of many dishes, including Raw Kibbé (Çiğ Köfte), that according to the legend, was crafted by the Prophet Abraham from ingredients he had at hand.[15] The walnut-stuffed Turkish dessert crepe (called şıllık) is a regional specialty.[16]

Many vegetables are used in the Urfa cuisine, such as the "'Ecır," the "Kenger," and the "İsot", the legendary local red capsicum that is a smaller and darker cultivar of the Aleppo pepper that takes a purplish black hue when dried and cured.

Unlike most of the Turkish cities that use different versions of regular butter in their regional cuisine, Urfa is, together with Antep, Mardin and Siirt a big user of clarified butter, made exclusively from sheep's milk, called locally "Urfayağı" ("Urfabutter").

Transport

Şanlıurfa GAP Airport is located about 34 km (21 mi) northeast of the city and has direct flights to Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir.

The first 7.7km section, connecting the city centre with the museum quarter, of a planned 4-route, 78km network of trolleybus lines opened on 16 October 2018. An initial fleet of 10 bi-articulated trolleybuses, together with all fixed equipment, has been supplied by manufacturer Bozankaya.[17]

Climate

Urfa has a hot summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification Csa). Urfa is very hot during the summer months. Temperatures in the height of summer usually reach 39 °C (102 °F). Rainfall is almost non-existent during the summer months. Winters are cool and wet. Frost is common and there is sporadic snowfall. Spring and autumn are mild and also wet.

| Climate data for Urfa (1960-2012) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.6 (70.9) |

25.5 (77.9) |

29.5 (85.1) |

36.4 (97.5) |

40.3 (104.5) |

44.1 (111.4) |

46.8 (116.2) |

46.2 (115.2) |

42.1 (107.8) |

37.8 (100.0) |

30.8 (87.4) |

26.0 (78.8) |

46.8 (116.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 10.0 (50.0) |

11.8 (53.2) |

16.5 (61.7) |

22.2 (72.0) |

28.6 (83.5) |

34.6 (94.3) |

38.7 (101.7) |

38.2 (100.8) |

33.8 (92.8) |

26.9 (80.4) |

18.5 (65.3) |

12.0 (53.6) |

24.3 (75.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.6 (42.1) |

6.9 (44.4) |

10.9 (51.6) |

16.1 (61.0) |

22.2 (72.0) |

28.2 (82.8) |

31.9 (89.4) |

31.2 (88.2) |

26.8 (80.2) |

20.2 (68.4) |

12.7 (54.9) |

7.5 (45.5) |

18.3 (65.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.3 (36.1) |

2.9 (37.2) |

6.2 (43.2) |

10.5 (50.9) |

15.6 (60.1) |

20.8 (69.4) |

24.4 (75.9) |

24.0 (75.2) |

20.1 (68.2) |

14.8 (58.6) |

8.4 (47.1) |

4.1 (39.4) |

12.8 (55.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −10.6 (12.9) |

−12.4 (9.7) |

−7.3 (18.9) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

2.5 (36.5) |

8.3 (46.9) |

15.0 (59.0) |

16.0 (60.8) |

10 (50) |

1.9 (35.4) |

−6 (21) |

−6.4 (20.5) |

−12.4 (9.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 86.5 (3.41) |

71.2 (2.80) |

64.3 (2.53) |

48.0 (1.89) |

28.3 (1.11) |

3.4 (0.13) |

0.7 (0.03) |

0.9 (0.04) |

2.9 (0.11) |

27.4 (1.08) |

46.6 (1.83) |

78.8 (3.10) |

459 (18.06) |

| Average rainy days | 12.4 | 11.3 | 10.9 | 9.8 | 6.5 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 2.9 | 5.3 | 8.1 | 11.2 | 80.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74 | 72 | 61 | 51 | 43 | 27 | 22 | 24 | 28 | 43 | 57 | 72 | 48 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 127.1 | 137.2 | 195.3 | 228 | 310 | 363 | 381.3 | 350.3 | 303 | 238.7 | 174 | 124 | 2,931.9 |

| Source 1: Devlet Meteoroloji İşleri Genel Müdürlüğü[18] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weatherbase[19] | |||||||||||||

Places of interest

- Urfa castle – built in antiquity, the current walls were constructed by the Abbasids in 814 AD.

- The legendary Pool of Sacred Fish (Balıklıgöl) where Abraham was thrown into the fire by Nimrod. The pool is in the courtyard of the mosque of Halil-ur-Rahman, built by the Kurdish Ayyubids in 1211 and now surrounded by the attractive Gölbaşı-gardens designed by architect Merih Karaaslan. The courtyard is where the fishes thrive. A local legend says seeing a white fish will open the door to the heavens.

- Rızvaniye Mosque – a more recent (1716) Ottoman mosque, adjoining the Balıkligöl complex.

- 'Ayn Zelîha – A source nearby the historical center, named after Zulaykha, a follower of Abraham.

- The Great Mosque of Urfa was built in 1170, on the site of a Christian church the Arabs called the "Red Church," probably incorporating some Roman masonry. Contemporary tradition at the site identifies the well of the mosque as that into which the towel or burial cloth (mendil) of Jesus was thrown (see Image of Edessa and Shroud of Turin). In the south wall of the medrese adjoining the mosque is the fountain of Firuz Bey (1781).

- Ruins of the ancient city walls.

- Eight Turkish baths built in the Ottoman period.

- The traditional Urfa houses were split into sections for family (harem) and visitors (selâm). There is an example open to the public next to the post office in the district of Kara Meydan.

- The Temple of Nevali Çori – Neolithic settlement dating back to 8000BC, now buried under the waters behind the Atatürk Dam, with some artefacts relocated above the waterline.

- Göbekli Tepe – The world's oldest known temple, dated 10th millennium BC (ca 11,500 years ago).[20]

Gallery

Mevlid-i Halil Mosque, built next to the site where prophet Abraham is believed to have been born.

Mevlid-i Halil Mosque, built next to the site where prophet Abraham is believed to have been born. 'Ayn Zelîha Lake

'Ayn Zelîha Lake Gölbaşı-Garden

Gölbaşı-Garden Ruins of Urfa castle

Ruins of Urfa castle Euphrates River

Euphrates River- Surrounding fields of Göbekli Tepe, the site of the oldest temple in the world.[20]

Notable people

- Matthew of Edessa – Historian

- Ephrem - Deacon, Hymn-writer, Theological writer

- Yusuf Nabi – 17th-century Ottoman poet

- Fuat Necati Öncel - politician

- Aysel Özakın - Turkish-British writer, born 1942

- Corinna Shattuck (1848-1910), American missionary at Urfa

- İbrahim Tatlıses (Ibo) – Kurdish singer

- Seyyal Taner- Turkish pop singer.

Twin towns and sister cities

See also

- Cilicia War

- Assyrian homeland

- Urfa Resistance

- Chronology of the Turkish War of Independence

- Knanaya

- Cities of the ancient Near East

- Haliliye

- Karaköprü

- Göbekli Tepe

References

- "Area of regions (including lakes), km²". Regional Statistics Database. Turkish Statistical Institute. 2002. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- Avcýkýran, Dr. Adem (ed.). "Kürtçe Anamnez, Anamneza bi Kurmancî" (PDF). Tirsik. p. 57. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Turkey: Major cities and provinces". citypopulation.de. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- Renfrew, Colin; Boyd, Michael J.; Morley, Iain (2016). Death Rituals and Social Order in the Ancient World: Death Shall Have No Dominion. Cambridge University Press. p. 74. ISBN 9781107082731.

- Segal, J. B. (2001) [1970]. "I. The Beginnings". Edessa:'The Blessed City' (2 ed.). Piscataway, New Jersey, United States: Gorgias Press. p. 5. ISBN 0-9713097-1-X.

It is certainly surprising that no obvious reference to Orhay has been found so far in the early historical texts dealing with the region, and that, unlike Harran, its name does not occur in cuneiform itineraries. This may be accidental, or Orhay may be alluded to under a different name which has not been identified. Perhaps it was not fortified, and therefore at this time a place of no great military significance. With the Seleucid period, however, we are on firm historical ground. Seleucus I founded—or rather re-founded—a number of cities in the region. Among them, probably in 303 or 302 BC, was Orhay.

- "TOMBOLARE — Urfa Man / Balıklıgöl Statue, c. 10,000 BC". Tumblr. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- Öktem, Kerem (2003). Creating the Turk's Homeland: Modernization, Nationalism and Geography in Southeast Turkey in the late 19th and 20th Centuries (PDF). Harvard: University of Oxford, School of Geography and the Environment, Mansfield Road, Oxford, OX1 3TB, UK. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

For Armenians, the city has a great symbolic value, as the Armenian alphabet was invented there, thanks to a group of scholars and clergy headed by Mesrop Mashtots in the 5th century

- Roberts, J. M. (1996). "II/4. Frontiers and neighbours". The Penguin History of Europe. London: Penguin Books. pp. 162–163. ISBN 978-0-14-026561-3.

- "Edessa". Jewish Encyclopedia. 1906.

- "Interview with Harun Bozo". The Library of Rescued Memories. Central Europe Center for Research and Documentation.

- Kinross, Lord (1977). The Ottoman Centuries, The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire. United States: Harper Perennial. pp. 560. ISBN 0-688-08093-6.

- Joseph, John (1983). Muslim-Christian Relations and Inter-Christian Rivalries in the Middle East: The Case of the Jacobites in an Age of Transition. United States: State University of New York Press. pp. 150. ISBN 0-87395-612-5.

- armenian-genocide.org

- "Kurds in Southeast Anatolia celebrate DTP's boost in votes". Today's Zaman. 31 March 2009. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- From Kâtib el Bağdadî in p.196Urfa'da Pişer Bize de Düşer, Halil & Munise Yetkin Soran, Alfa Yayın, 2009, Istanbul ISBN 978-605-106-065-1

- "Şanlıurfa'nın 'şıllık' tatlısı tescillendi". Sabah. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- Metro Report International (24 Oct 2018) https://www.metro-report.com/news/single-view/view/sanliurfa-trolleybus-route-opens.html

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 20 June 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.weatherbase.com/weather/weatherall.php3?s=7271&refer=&units=us&cityname=Urfa-Turkey

- "The World's First Temple - Archaeology Magazine Archive". archive.archaeology.org. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Şanlıurfa. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Urfa. |

- Şanlıurfa Governor's Office (English)

- Urfa Haber

- Old and new photos

- Sanliurfa Mayor's Office

- Tourism information is available in English at the Southeastern Anatolian Promotion Project site.

- Photos from Balikli Gol in the old part of Urfa

- Over 1000 pictures of sites in town