Syriac Orthodox Church

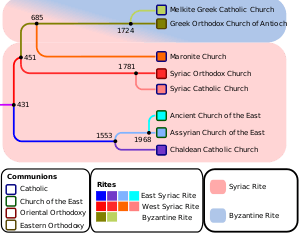

The Syriac Orthodox Church (Classical Syriac: ܥܺܕܬܳܐ ܣܽܘ̣ܪܝܳܝܬܳܐ ܬܪܺܝܨܰܬ ܫܽܘ̣ܒ̣ܚܳܐ, romanized: ʿIdto Suryoyto Triṣaṯ Šuḇḥo; Arabic: الكنيسة السريانية الأرثوذكسية), or Syriac Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch and All the East, or informally the Jacobite Church, is a Oriental Orthodox church branched from the Church of Antioch. The Bishop of Antioch, known as the Patriarch, heads the church, claiming apostolic succession through Saint Peter (Classical Syriac: ܫܸܡܥܘܿܢ ܟܹ݁ܐܦ݂ܵܐ, romanized: Šemʿōn Kēp̄ā) in the c. 1st century, according to sacred tradition.[9][10] The autocephalous patriarchate was established in Antioch by Severus the Great in the c. 6th century and was organized by Jacob Baradaeus (c. 500-578) in rejection of Dyophysitism.[11][12][13]

Syriac Orthodox Church | |

|---|---|

| Classical Syriac: ܥܺܕܬܳܐ ܣܽܘ̣ܪܝܳܝܬܳܐ ܬܪܺܝܨܰܬ ܫܽܘ̣ܒ̣ܚܳܐ | |

| |

| Type | Antiochian |

| Classification | Eastern Christian |

| Orientation | Oriental Orthodox |

| Scripture | Peshitta |

| Theology | Miaphysitism |

| Polity | Episcopal |

| Structure | Communion |

| Patriarch | Ignatius Aphrem II Patriarch |

| Catholicate of India | Jacobite Syrian Christian Church |

| Associations | World Council of Churches |

| Region | Middle East, India, and diaspora |

| Language | Classical Syriac |

| Liturgy | West Syriac: Liturgy of Saint James |

| Headquarters | Cathedral of Saint George, Damascus, Syria (since 1959) |

| Origin | 1st century *[1][2][3] Antioch, Roman Empire[4][5] |

| Independence | 518 A.D.[6] |

| Branched from | Church of Antioch[7] |

| Aid organization | EPDC St. Ephrem Patriarchal Development Committee[8] |

| Official website | Syriac Orthodox Patriarchate |

| *Origin is according to Sacred tradition. West Syriac Cross Unicode (U+2670) : ♰ | |

| Part of a series on |

| Oriental Orthodoxy |

|---|

|

| Oriental Orthodox churches |

|

Subdivisions

|

|

History and theology

|

|

Major figures

|

|

|

The church employs the Divine Liturgy of Saint James, associated with James, the "brother" of Jesus and leader among the Jewish Christians at Jerusalem.[14] Syriac is the official and liturgical language of the church. Mor Hananyo Monastery was the headquarters of the church from c. 1160 until 1932.[15] The patriarchate was transferred to Homs due to the effects of World War I. The current see of the church is the Cathedral of Saint George, Bab Tuma, Damascus, Syria, since 1959.[16][17][18] Since 2014, Ignatius Aphrem II is the current Patriarch of Antioch. The church has archdioceses and patriarchal vicariates in countries covering six continents. Being an active member of World Council of Churches, the church participates in various ecumenical dialogues with other churches.

Name and identity

Syriac-speaking Christians have referred to themselves as "Ārāmayē/Āṯūrāyē/Sūryāyē" in native Aramaic terms based on their ethnic identity.[19] In most languages besides English, a unique name has long been used to distinguish the church from the polity of Syria. In Arabic (the official language of Syria), the church is known as the "Suriania Church" as the term "Suriania" identifies the Syriac language. Chalcedonians referred to the church as "Jacobite" (after Jacob Baradaeus) since the Nestorian Schism in the c. 5th century.[20] English-speaking historians identified the church as the "Syrian Church". The English term "Syrian" (from Aramaic: "Aššūrāyu"; "Assyria") was used to describe the community of Assyrian people in ancient Syria. In the 15th century, the term "Orthodox" (from Greek: "orthodoxía"; "correct opinion") was used to identify churches that practiced the set of doctrines believed by the early Christians. Since 1922, the term "Syrian" started being used for things named after the Syrian Federation. Hence, in 2000, the Holy Synod ruled that the church be named as "Syriac Orthodox Church" after the Syriac language, the official liturgical language of the church.[21]

The ethnic groups in the community contest their ethnic identification as "Assyrians" and "Arameans".[22] "Suryoye" is the term used to identify the Syriacs in the diaspora.[23] The Syriac Orthodox identity included auxiliary cultural traditions of the pagan Assyria and Aramean kingdoms.[24] Church traditions crystallized into ethnogenesis through the preservation of their stories and customs by the 12th century. Syriac Orthodox intellectuals predominantly used the "Assyrian" identification in the 19th century. Since the 1910s, the identity of Syriac Orthodoxy in the Ottoman Empire was principally religious and linguistic.[25][26]

History

Early history

The church claims apostolic succession through the pre-Chalcedonian Patriarchate of Antioch to the Early Christian communities from Jerusalem led by Saint Barnabas and Saint Paul in Antioch, during the Apostolic era, as described in the Acts of the Apostles; "The disciples were first called Christians in Antioch" (New Testament, Acts 11:26). Saint Peter was selected by Jesus Christ (New Testament, Matthew 16:18) and is venerated as the first bishop of Antioch in c. 37 A.D. after the Incident at Antioch.[27][28][29]

Saint Evodius was Bishop of Antioch until 66 AD and was succeeded by Saint Ignatius of Antioch.[30] The earliest recorded use of the term "Christianity" (Greek: Χριστιανισμός) was by Ignatius of Antioch, in around 100 AD.[31] In A.D 169, Theophilus of Antioch wrote three apologetic tracts to Autolycus.[32] Patriarch Babylas of Antioch was considered the first saint recorded as having had his remains moved or "translated" for religious purposes—a practice that was to become extremely common in later centuries.[33] Eustathius of Antioch supported Athanasius of Alexandria who opposed the followers of the condemned doctrine of Arius (Arian controversy) at the First Council of Nicaea.[34] During the time of Meletius of Antioch the church split due to his being deposed for Homoiousian leanings—which became known as the Meletian Schism and saw several groups and several claimants to the See of Antioch.[35][36][37][38]

Patriarchate of Antioch

Given the antiquity of the Bishopric of Antioch and the importance of the Christian community in the city of Antioch, a commercially significant city in the eastern parts of the Roman Empire, the First Council of Nicaea (325) recognized the Bishopric as a Primacy (Patriarchate), along with the Bishoprics of Rome, Alexandria, and Jerusalem, bestowing authority for the "Church of Antioch and All of the East" on the Patriarch.[39][40] Because of the significance attributed to Ignatius of Antioch in the church, most of the Syriac Orthodox patriarchs since 1293 have used the name of Ignatius in the title of the Patriarch preceding their own Patriarchal name.[41]

Even though the Synod of Nicaea was convened by the Roman Emperor Constantine, the authority of the ecumenical synod was also accepted by the Church of the East which was politically isolated from the churches in the Roman Empire.[42] Until Synod of Beth Lapat, Church of the East accepted the spiritual authority of the Patriarch of Antioch. The Christological controversies that followed the Council of Chalcedon in 451 resulted in a long struggle for the Patriarchate between those who accepted and those who rejected the Council.[43] Flavian II of Antioch was appointed as Patriarch by Emperor Anastasius I in c. 498 A.D.[44]

In c. 518 A.D., Patriarch Severus the Great was exiled from the city of Antioch by Byzantine Emperor Justin I, who enforced a uniform Chalcedonian Christian orthodoxy throughout the empire.[45][46][47] Those who sought communion with Rome and Constantinople accepted the Council of Chalcedon and the formula of Pope Hormisdas and recognized the new Chalcedonian Patriarch of Antioch Paul the Jew. The patriarchate was forced to move from Antioch with Severus the Great who took refuge in Alexandria. The non-Chalcedonian community was divided between "Severians", followers of Severus, and aphthartodocetae, and divisions remained unresolved until 527.[48] Severians continued to recognize Severus as the legitimate Patriarch even after his exile in 518 until his death in 538.

Bishop Jacob Baradaeus (died 578) is credited for ordaining most of the miaphysite hierarchy while facing heavy persecution in the 6th century. In 544, Jacob Baradeus ordained Sergius of Tella continuing the non-Chalcedonian succession of patriarchs of the Church of Antioch.[49] That was done in opposition to the government-backed Patriarchate of Antioch held by the pro-Chalcedonian believers leading to the Syriac Orthodox Church being known popularly as the "Jacobite" Church, while the Chalcedonian believers were known popularly as Melkites—coming from the Syriac word for king (malka), an implication of the Chalcedonian Church's relationship to the Roman Emperor (later emphasised by the Melkite Greek Catholic Church).[50] Because of many historical upheavals and consequent hardships that the Syriac Orthodox Church had to undergo, the patriarchate was transferred to different monasteries in Mesopotamia for centuries. John III of the Sedre was elected and consecrated Patriarch after the death of Athanasius I Gammolo in 631 A.D., followed by the fall of Roman Syria and the Muslim conquest of the Levant. John and several bishops were summoned before Emir Umayr ibn Sad al-Ansari of Hims to engage in open debate regarding Christianity and represent the entire Christian community, including non-Syriac Orthodox communities, such as Greek Orthodox Syrians.[51] The Emir demanded translations of the Gospels into Arabic to confirm John's beliefs, which according to the Chronicle of Michael the Syrian was the first translation of the Gospels into Arabi

Transfer to new locations During 1160,[52] the patriarchate was transferred from Antioch to Mor Hananyo Monastery (Deir al-Za`faran), in southeastern Anatolia near Mardin, where it remained until 1933 and re-established in Homs, Syria, due to the adverse political situation in Turkey. In 1959, the patriarchate was transferred to Damascus. The mother church and official seat of the Syriac Orthodox Church are now situated in Bab Tuma, Damascus, capital of Syria.

Middle Ages

The 8th-century hagiography Life of Jacob Baradaeus is evidence of a definite social and religious differentiation between the Chalcedonians and Miaphysites (Syriac Orthodox).[53] The longer hagiography shows that the Syriac Orthodox (called "Jacobites" in the work, suryoye yaquboye) self-identified with Jacob's story more than those of other saints.[54] Coptic Bishop Severus ibn al-Muqaffa (ca. 897), of Miaphysite (Syriac Orthodox) ancestry, speaks of Jacobite origins, on the veneration of Jacob Baradaeus. He explained that the Chalcedonian "Melkites" were labeled as such because the Miaphysite Jacobites never traded their Orthodoxy to win the favor of the king as the Melkites had done (malko is derived from "king, ruler").[55][56]

In Antioch, after the 11th-century persecutions, the Syriac Orthodox population was almost extinguished.[57] Only one Jacobite church is attested in Antioch in the first half of the 12th century, while a second and third are attested in the second half of the century, perhaps due to refugee influx.[57] Dorothea Weltecke thus concludes that the Syriac Orthodox populace was very low in this period in Antioch and surroundings.[57] In Adana, an anonymous 1137 report speaks of the entire population consisting of Syriac Orthodox.[57] In the 12th century, several Syriac Orthodox Patriarchs visited Antioch and some established temporary residences.[58] In the 13th century, the Syriac Orthodox hierarchy in Antioch was prepared to accept Latin supervision.[59] The Syriac Orthodox were the most numerous non-Latin sect in Jerusalem and Bethlehem before 1187.[60] Before the advent of the Crusades, the Syriacs occupied most of the hill country of Jazirah (Upper Mesopotamia).[61]

Early modern period

16th century

Moses of Mardin (fl. 1549–d. 1592) was a diplomat of the Syriac Orthodox Church in Rome in the 16th century.[62]

17th century

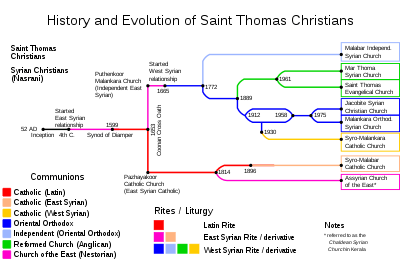

By the early 1660s, 75% of the 5,000 Syriac Orthodox of Aleppo had converted to Roman Catholicism following the arrival of mendicant missionaries.[63] The Catholic missionaries had sought to place a Catholic Patriarch among the Jacobites and consecrated Andrew Akhijan as the Patriarch of the newly founded Syriac Catholic Church.[63] The Propaganda Fide and foreign diplomats pushed for Akhijan to be recognized as the Jacobite Patriarch, and the Porte then consented and warned the Syriac Orthodox that they would be considered an enemy if they did not recognize him.[64] Despite the warning and gifts to priests, frequent conflicts and violent arguments continued between the Catholic and Orthodox Syriacs.[64] Around 1665, many Saint Thomas Christians of Kerala, India, committed themselves in allegiance to the Syriac Orthodox Church, which established the Malankara Syrian Church, reuniting with the See of Antioch for the first time since the schism of the Church of the East from the jurisdiction of Antioch in 484 after the execution of Babowai. The Malankara Church consolidated under Mar Thoma I welcomed Gregorios Abdal Jaleel, who regularised the canonical ordination of Mar Thoma I as a native democratically elected Bishop of the Malabar Syrian Christians.[65]

Late modern period

In the 19th century, the various Syriac Christian denominations did not view themselves as part of one ethnic group.[66] During the Tanzimat reforms (1839–78), the Syriac Orthodox was granted independent status by gaining recognition as their own millet in 1873, apart from Armenians and Greeks.[67]

In the late 19th century, the Syriac Orthodox community of the Middle East, primarily from the cities of Adana and Harput, began the process of creating the Syriac diaspora, with the United States being one of their first destinations in the 1890s.[68] Later, in Worcester, the first Syriac Orthodox Church in the United States was built.[69]

The 1895–96 massacres in Turkey affected the Armenian and Syriac Orthodox communities when an estimated 105,000 Christians were killed.[70] By the end of the 19th century, 200,000 Syriac Orthodox Christians remained in the Middle East, most concentrated around Saffron Monastery, the Patriarchal Seat.[71]

In 1870, there were 22 Syriac Orthodox settlements in the vicinity of Diyarbakır.[72] In the 1870–71 Diyarbakır salnames, there were 1,434 Orthodox Syriacs in that city.[73][74] On 10 December 1876, Ignatius Peter IV consecrated Geevarghese Gregorios of Parumala as metropolitan.[75] Rivalry within the Syriac Orthodox Church in Tur Abdin resulted in many conversions to the Syriac Catholic Church (the Uniate branch).[76]

Genocide (1914–18)

The Ottoman authorities killed and deported Orthodox Syriacs, then looted and appropriated their properties.[77] During 1915–16, the number of Orthodox Syriacs in the Diyarbakır province was reduced by 72%, and in the Mardin province by 58%.[78]

Interwar period

In 1924, the patriarchate of the Church was transferred to Homs after Kemal Atatürk expelled the Syriac Orthodox Patriarch, who took the library of Deir el-Zaferan and settled in Damascus.[79][71] The Syriac Orthodox villages in Tur Abdin suffered from the 1925–26 Kurdish rebellions and massive flight to Lebanon, northern Iraq and especially Syria ensued.[80]

In the early 1920s, the city of Qamishli was built mainly by Syriac Orthodox refugees, escaping the Assyrian genocide.

1945–2000

In 1959, the seat of the Syriac Orthodox Church was transferred to Damascus in Syria.[79] In the mid-1970s, the estimate of Syriac Orthodox lived in Syria is 82,000.[81] In 1977, the number of Syriac Orthodox followers in diaspora dioceses was: 9,700 in the Diocese of Middle Europe; 10,750 in the Diocese of Sweden and surrounding countries.[82]

On 20 October 1987, Geevarghese Mar Gregorios of Parumala was declared a saint by Ignatius Zakka I Iwas, Patriarch permitting additions to the diptychs.[83][84]

Leadership

Patriarch

The supreme head of the Syriac Orthodox Church is named Patriarch of Antioch, in reference to his titular pretense to one of the five patriarchates of the Pentarchy of early Eastern Christianity. Considered the "father of fathers", he must be an ordained bishop. He is the general administrator to Holy Synod and supervises the spiritual, administrative, and financial matters of the church. He governs external relations with other churches and signs agreements, treaties, contracts, pastoral encyclicals (bulls), pastoral letters related to the affairs of the church.[85]

Bishops

The title bishop comes from the Greek word episkopos, meaning "the one who oversees".[86] A bishop is a spiritual ruler of the church who has different ranks. The highest rank in the ecclesiastical hierarchy is the Patriarch. The second-highest rank is the Maphrian, also known as Catholicos of India, who is the head of the Malankara Syrian Jacobite Church in India. Then there are Metropolitan bishops or Archbishops, and under them, there are auxiliary bishops. Historically, in the Malankara Church, the local chief was called as Archdeacon, who was the ecclesiastical authority of the Saint Thomas Christians in the Malabar region of India.[87]

Priests

The priest is the seventh rank and is the one duly appointed to administer the sacraments. Unlike in the Roman Catholic Church, Syriac deacons may marry before ordained as priests; they cannot marry after ordained as priests. There is an honorary rank among the priests that are Corepiscopos who has the privileges of "first among the priests" and is given a chain with a cross and specific vestment decorations. Corepiscopos is the highest rank a married man can be elevated to in the Syriac Orthodox Church. The ranks above the Corepiscopos are unmarried.

Deacons

In the Syriac Orthodox tradition, different ranks among the deacons are specifically assigned with particular duties. The six ranks of the diaconate are:

- ‘Ulmoyo (Faithful)

- Mawdyono (Confessor of faith)

- Mzamrono (Singer)

- Quroyo (Reader)

- Afudyaqno (Sub-deacon)

- Masamsono (Full deacon)

Only a full deacon can take the censer during the Divine Liturgy to assist the priest. In Jacobite Syrian Christian Church, because of the lack of deacons, altar assistants who do not have a rank of deaconhood may assist the priest. Historically the Malankara Church was administered by a local chief called Archdeacon ("Arkadiyokon").

Deaconess

An ordained deaconess is entitled to enter the sanctuary only for cleaning, lighting the lamps and is limited to give Holy Communion to women and the children who are under the age of five.[88] She can read scriptures, Holy Gospel in a public gathering. The name of deaconess can also be given to a choirgirl. Deaconess is not ordained as chanter before reaching fifteen years of age. The ministry of the deaconess assists the priest and deacon outside the altar including in the service of baptizing women and anointing them with holy chrism.[89]

Worship

Bible

Syriac Orthodox Churches use the Peshitta (Syriac: simple, common) as its Bible. The New Testament books of this Bible are estimated to have been translated from Greek to Syriac between the late 1st century to the early 3rd century AD.[90] The Old Testament of the Peshitta was translated from Hebrew, probably in the 2nd century. The New Testament of the Peshitta, which originally excluded certain disputed books, had become the standard by the early 5th century, replacing two early Syriac versions of the gospels.

Doctrine

The Syriac Orthodox Church theology is based on the Nicene Creed. The Syriac Orthodox Church teaches that it is the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church founded by Jesus Christ in his Great Commission,[91] that its metropolitans are the successors of Christ's Apostles, and that the Patriarch is the successor to Saint Peter on whom primacy was conferred by Jesus Christ.[92][93] The church accepted first three synods held at Nicaea (325), Constantinople (381), and Ephesus (431), shaping the formulation and early interpretation of Christian doctrines.[94] The Syriac Orthodox Church is part of Oriental Orthodoxy, a distinct communion of Churches claiming to continue the Patristic and Apostolic Christology before the schism following the Council of Chalcedon in 451.[95] In terms of Christology, the Oriental Orthodox (Non-Chalcedonian) understanding is that Christ is "One Nature—the Logos Incarnate, of the full humanity and full divinity". Just as humans are of their mothers and fathers and not in their mothers and fathers, so too is the nature of Christ according to Oriental Orthodoxy. The Chalcedonian understanding is that Christ is "in two natures, full humanity and full divinity". This is the doctrinal difference that separated the Oriental Orthodox from the rest of Christendom. The church believes in the mystery of Incarnation and venerate Virgin Mary as Theotokos or Yoldath Aloho (Meaning: ‘Bearer of God’).[96][97]

The Fathers of the Syriac Orthodox Church gave a theological interpretation to the primacy of Saint Peter.[98] They were fully convinced of the unique office of Peter in the early Christian community. Ephrem, Aphrahat, and Maruthas unequivocally acknowledged the office of Peter. The different orders of liturgies used for sanctification of church buildings, marriages, ordinations etc., reveal that the primacy of Peter is a part of faith of the church. The church does not believe in Papal Primacy as understood by the Roman See, rather, Petrine Primacy according to the ancient Syriac tradition.[99] The church uses both Julian calendar and Gregorian calendar based on their regions and traditions they adapted.

Language

- Classical Syriac: The Syriac language, of the Semitic Aramaic family, is the literary language of the Syriac Orthodox Church. In Tur Abdin, Turoyo is the Neo-Aramaic dialect spoken by the Syriac Orthodox community. The Turoyo-speaking population prior to the 1915 genocide largely adhered to the Syriac Orthodox Church.[100][101] This Language is used Globally with regional languages for Liturgy.

- Arabic had become the dominant language of Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, and Egypt by the 11th century.[102] Syriac Orthodox clergy wrote in Arabic using Garshūni, a Syriac script in the 15th century and later adopted the Arabic script.[102] An English missionary in the 1840s noted that the Arabic speech of the Syriacs was intermixed with Syriac vocabulary.[102] They chose Arabic and Muslim-sounding names, while women had Biblical names.[102]

- English: Used Globally along with Syriac.

- Malayalam, Tamil, Kannada are presently used in India. Suriyani Malayalam, also known as Karshoni or Syriac Malayalam, is a dialect of Malayalam written in a variant form of the Syriac alphabet which was popular among the Saint Thomas Christians (also known as Syrian Christians or Nasranis) of Kerala in India.[103][104][105][106] It uses Malayalam grammar, the Maḏnḥāyā or "Eastern" Syriac script with special orthographic features, and vocabulary from Malayalam and East Syriac. This originated in the South Indian region of the Malabar Coast (modern-day Kerala). Until the 19th century, the script was widely used by Syrian Christians in Kerala.

- Swedish, German, Dutch, Turkish, Spanish, Portuguese are used in diasporas along with Syriac.[107][108]

Liturgy

The liturgical service is called Holy Qurobo in the Syriac language meaning "Eucharist". Liturgy of Saint James is celebrated on Sundays and special occasions. The Holy Eucharist consists of Gospel reading, Bible readings, prayers, and songs. The recitation of the Liturgy is performed according to with specific parts chanted by the presider, the lectors, the choir, and the congregated faithful, at certain times in unison. Apart from certain readings, prayers are sung in the form of chants and melodies. Hundreds of melodies remain preserved in the book known as Beth Gazo, the key reference to Syriac Orthodox church music.[109]

Prayer

Syriac Orthodox clergy and some devout laity follow a regimen of seven prayers a day, in accordance with Psalm 119.[110] According to the Syriac tradition, an ecclesiastical day starts at sunset and the Canonical hours are based on West Syriac Rite:

- Evening or Ramsho prayer (Vespers)[111]

- Night prayer or Sootoro prayer (Compline)[112]

- Midnight or Lilyo prayer (Matins)

- Morning or Saphro prayer (Prime or Lauds, 6 a.m.)

- Third Hour or tloth sho`in prayer (Terce, 9 a.m.)

- Sixth Hour or sheth sho`in prayer (Sext, noon)

- Ninth Hour or tsha` sho'in prayer (None, 3 p.m.)

Sacraments

The seven Holy Sacraments of the church are:

- Chrismation (Smearing of Holy Muron)

- Baptism

- Confession

- Holy Communion (Queen of the Sacraments)[113]

- Marriage

- Unction (Anointing of the Sick)

- Ordination[114]

Vestments

The clergy of the Syriac Orthodox Church has unique liturgical vestments with their order in the priesthood: the deacons, the priests, the chorbishops, the bishops, and the patriarch each have different vestments.[115]

Bishops usually wear a black or a red robe with a red belt. They should not wear a red robe in the presence of the patriarch, who wears a red robe. Bishops visiting a diocese outside their jurisdiction also wear black robes in deference to the bishop of the diocese, who alone wears red robes. They carry a crosier stylised with serpents representing the staff of Moses during sacraments. Corepiscopos wear a black or a purple robe with a purple belt. Bishops and corepiscopos have hand-held crosses.[116]

A priest also wears a phiro, or a cap, which he must wear for the public prayers. Monks also wear eskimo, a hood. Priests also have ceremonial shoes which are called msone. Without wearing these shoes, a priest cannot distribute Eucharist to the faithful. Then there is a white robe called kutino symbolizing purity. Hamniko or stole is worn over this white robe. Then he wears a girdle called zenoro, and zende, meaning sleeves. If the celebrant is a bishop, he wears a masnapto, or turban (different from the turbans worn by Sikh men). A cope called phayno is worn over these vestments. Batrashil, or pallium, is worn over the phayno by bishops, like hamnikho worn by priests.[117] The priest's usual dress is a black robe. In India, due to the hot weather, priests usually wear white robes except during prayers in the church, when they wear a black robe over the white one. Deacons wear a phiro, white kutino(robe) and of rank Quroyo and higher wear an uroro 'stole' in various shapes according to their rank. The deaconess wears a stole (uroro) hanging down from the shoulder in the manner of an archdeacon.[118]

Global presence

Demography

The Patriarchate was initially established in Antioch (present-day Syria, Turkey, and Iraq), due to the persecutions by Romans followed by Muslim Arabs, the Patriarchate was seated in Mor Hananyo Monastery, Mardin, in the Ottoman Empire (1160-1933); following Homs (1933-1959); and Damascus, Syria, since 1959. Historically, the followers of the church are mainly ethnic Assyrians who comprise the indigenous pre-Arab populations of modern Syria, Iraq and southeastern Turkey.[119] A diaspora has also spread from the Levant, Iraq, and Turkey throughout the world, notably in Sweden, Germany, United Kingdom, Netherlands, Austria, France, United States, Canada, Guatemala, Argentina, Brazil,Pakistan,Indonesia, Australia, and New Zealand.

The Church's members are divided into 26 Archdioceses, and 13 Patriarchal Vicariates.[120]

It is estimated that the church has 500,000 Assyrian adherents, in addition to 2 million members of the Jacobite Syrian Christian Church and their own ethnic diaspora in India.[95][121][122] Additionally, there is also a large Syriac community among Mayan converts in Guatemala.

The number of Assyrians in Turkey is rising, due to refugees from Syria and Iraq fleeing ISIS, as well as Assyrians from the Diaspora who fled the region during the Turkey-PKK conflict (since 1978) returning and rebuilding their homes. The village of Kafro was populated by Syriacs from Germany and Switzerland.[123][124]

In the Syriac diaspora, there are approximately 80,000 members in the United States, 80,000 in Sweden, 100,000 in Germany, 15,000 in the Netherlands, 200,000 members in Brazil, Switzerland, and Austria.[125]

Jurisdiction of the patriarchate

The Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch originally covered the whole region of the Middle East and India. In recent centuries, its parishioners started to emigrate to other countries over the world. Today, the Syriac Orthodox Church has several archdioceses and patriarchal vicariates (exarchates) in many countries covering six continents.

- Patron: The Patriarch of Antioch and All the East, the Supreme Head of the Universal Syriac Orthodox Church Ignatius Aphrem II.

- Patriarchal Seat: Cathedral of Saint George, Damascus, Syria

- Headquarters and patriarchal office: Damascus

Americas

The presence of the Syrian Orthodox faithful in America dates back to the late 19th century.[126][127]

North America

- Patriarchal Vicariate of Eastern United States[128][129]

- Patriarchal Vicariate of Western United States [130]

- Malankara Archdiocese of North America

- Patriarchal Vicariate of Canada.[131]

Central America

In the Guatemala region, a Charismatic movement emerged in 2003 was excommunicated in 2006 by the Roman Catholic Church later joined the church in 2013. Members of this archdiocese are Mayan in origin and live in rural areas, and display charismatic-type practices.[132]

- Archdiocese of Central America, the Caribbean Islands and Venezuela[133][134][135]

South America

Eurasia

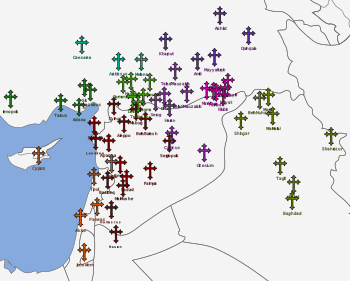

Middle East regions

Syriac Orthodox Church in the Middle East and the diaspora, numbering between 150,000 and 200,000 people in their indigenous area of habitation in Syria, Iraq, and Turkey according to estimations.[138] The community formed and developed in the Middle Ages. The Syriac Orthodox Christians of the Middle East speak Aramaic. Archbishoprics in the Middle East include regions of Jazirah, Euphrates, Aleppo, Homs, Hama, Baghdad, Basrah, Mosul, Kirkuk, Kurdistan, Mount Lebanon, Beirut, Istanbul, Ankara and Adiyaman,[139] Israel, Palestine, Jordan.[140][141][142]

Patriarchal Vicariates in the Middle East includes Damascus, Mardin, Turabdin, Zahle, UAE and the Arab States of the Persian Gulf.

India

Syriac Orthodox Church of Malankara (India)

The Jacobite Syrian Christian Church, one of the various Saint Thomas Christian churches in India, is an integral part of the Syriac Orthodox Church, with the Patriarch of Antioch as its supreme head. The local head of the church in Malankara (Kerala) is Baselios Thomas I, ordained by Patriarch Ignatius Zakka I Iwas in 2002 and accountable to the Patriarch of Antioch. The headquarters of the church in India is at Puthencruz near Ernakulam in the state of Kerala in South India. Simhasana Churches and Honavar Mission is under the direct control of Patriarch. Historically, the St. Thomas Christians were part of the Church of the East, based in Persia which was under the Patriarch of Antioch until Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon(410 AD.) and reunited with Syriac Orthodox Patriarchs of Antioch since c. 1652.[143] Assyrian monks Mar Sabor and Mar Proth arrived at Malankara between the 8th and 9th centuries from Persia.[144] They established churches in Quilon, Kadamattom, Kayamkulam, Udayamperoor, and Akaparambu.[145]

The Malankara Marthoma Syrian Church is an independent reformed church under the jurisdiction of Marthoma Metropolitan and its first Reforming Metropolitan Mathews Athanasius was ordained by Ignatius Elias II in 1842.[146] Catholicate was re-established in Malankara in 1912 by Ignatius Abded Mshiho II by the consecration of Paulose I as first Catholicos. Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church accepts the Patriarch of Antioch only as its spiritual Father as stated by the constitution of 1934.[147]

Knanaya Arch Diocese

The Knanaya Syriac Orthodox Church is an archdiocese under the guidance and direction of Archbishop Severious Kuriakose with the patriarch as its spiritual head. They are the followers of the Syrian merchant Knāy Thoma (Thomas of Cana) in the 4th or 8th century, while another legend traces their origin to Jews in the Middle East.[148][149][150][151]

Evangelistic Association Of The East

E.A.E Arch Diocese is the missionary association of Syriac Orthodox Church founded in 1924 by Geevarghese Athunkal Cor-Episcopa at Perumbavoor.[152] This archdiocese is under the direct control of the patriarch under the guidance of Chrysostomos Markose, It is an organization with churches, educational institutions, orphanages, old age homes, convents, publications, mission centers, gospel teams, care missions, and a missionary training institute. It is registered in 1949 under the Indian Societies Registration Act. XXI of 1860 (Reg. No. S.8/1949ESTD 1924).[153][154][155]

Europe

Earlier in the 20th century many Syrian Orthodox immigrated to Western Europe diaspora, located in the Sweden, Netherlands, Germany, and Switzerland for economic and political reasons.[156][157] Dayro d-Mor Ephrem in Netherlands is the first Syriac Orthodox monastery in Europe established in 1981.[158] Dayro d-Mor Awgen, Arth, Switzerland,Dayro d-Mor Ya`qub d-Sarug, Warburg, Germany are the other monasteries located in Europe.

Patriarchal Vicariates:

Oceania

- Australia and New Zealand

- Patriarchal Vicariate of Australia and New Zealand under Archbishop Malatius Malki Malki.[163][164][165]

Institutions

The church has various seminaries, colleges, and other institutions.[166] Patriarch Aphrem I Barsoum established St. Aphrem's Clerical School in 1934 in Zahlé. In 1946, the school was moved to Mosul, where it provided the church with a selection of graduates, the first among them being Patriarch Ignatius Zakka I Iwas and many other church leaders. In 1990, the Order of St. Jacob Baradaeus was established for nuns. Seminaries have been instituted in Sweden and in Salzburg for the study of Syriac theology, history, language, and culture. Happy Child House project started in 2019 provides childcare services in Damascus, Syria. The church has an international Christian education center for religious education.[167] The Antioch Syrian University was established on 8 September 2018 in Maarat Saidnaya, near Damascus.[168] The university is offering engineering, management and economics courses.[169]

Ecumenical relations

The Syriac Orthodox Church is active in ecumenical dialogues with various churches including the Roman Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox Churches, Anglican Communion, Russian Orthodox Church, Assyrian Church of the East and other Non-Chalcedonian Churches. The Church is an active member of the World Council of Churches since 1960 and Patriarch Ignatius Zakka I Iwas was one of the former presidents of WCC. It has also been involved in the Middle East Council of Churches since 1974. There are common Christological and pastoral agreements with the Catholic Church by the 20th century as the Chalcedonian schism was not seen with the same relevance, and from several meetings between the authorities of the Catholic Church and the Oriental Orthodoxy, reconciling declarations emerged in the common statements of the Patriarch Ignatius Jacob III and Pope Paul VI in 1971, Patriarch Ignatius Zakka I Iwas and Pope John Paul II in 1984:

The confusions and schisms that occurred between their Churches in the later centuries, they realise today, in no way affect or touch the substance of their faith, since these arose only because of differences in terminology and culture and in the various formulae adopted by different theological schools to express the same matter. Accordingly, we find today no real basis for the sad divisions and schisms that subsequently arose between us concerning the doctrine of Incarnation. In words and life, we confess the true doctrine concerning Christ our Lord, notwithstanding the differences in interpretation of such a doctrine which arose at the time of the Council of Chalcedon.[170]

The precise differences in theology that caused the Chalcedonian controversy is said to have arisen "only because of differences in terminology and culture and in the various formulae adopted by different theological schools to express the same matter", according to a common declaration statement between Patriarch Ignatius Jacob III and Pope Paul VI on Wednesday 27 October 1971. In 2015, Pope Francis addressed the Syriac Orthodox Church as "a Church of Martyrs " welcoming the visit of Ignatius Aphrem II to Holy See.[171] In 2015, Ignatius Aphrem II visited Patriarch Kirill of Moscow of the Russian Orthodox Church and discussed prospects of bilateral and theological dialogue existing since the late 1980s.[172] Since 1998, the heads of the Oriental Orthodox churches including Coptic Orthodox Church, Armenian Apostolic Church participates in Interfaith dialogues each year.[41]

See also

- List of Syriac Orthodox Patriarchs of Antioch

- Dioceses of the Syriac Orthodox Church

- Syriac Christianity

- Oriental Orthodoxy

- Patriarchate of Alexandria

- Miaphysitism, Cyril of Alexandria's Christology

Communities

- Assyrians/Syriacs originating from Middle East´

- Turabdin in Turkey, former Syriac cultural heartland

- Saffron Monastery, important site in Turabdin

- Turabdin in Turkey, former Syriac cultural heartland

- Saint Thomas Christians in India

- Malankara Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church

- Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church (Indian Orthodox Church)

- Södertälje, Swedish town with many Syriac people and churches

- Guatemalans (recent convert activity)

References

- Chaillot, Christine (1998). The Syrian Orthodox Church of Antioch and All the East: A Brief Introduction to Its Life and Spirituality. Inter-Orthodox Dialogue. pp. 21–22.

- Beggiani, Seely J. (2014). Early Syriac Theology. CUA Press. ISBN 9780813227016.

- Simon, Thomas Collins (1862). The Mission and Martyrdom of St. Peter: Or, Did St. Peter Ever Leave the East? Containing the Original Text of All the Passages in Ancient Writers Supposed to Imply a Journey Into Europe, with Translations and Roman-catholic Comments ... by Thomas Collyns Simon. Rivingtons. p. 70.

- "Cave Church of St. Peter - Antioch, Turkey". www.sacred-destinations.com.

- "BBC - Religions - Christianity: Eastern Orthodox Church". www.bbc.co.uk.

- Rassam, Suha (2005). Christianity in Iraq: Its Origins and Development to the Present Day. Gracewing Publishing. ISBN 9780852446331.

- "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Church of Antioch". www.newadvent.org.

- "St. Ephrem Patriarchal Development Committee". Humanitarian Aid Relief Trust.

- Gregorios, Paulos (1999). Introducing the Orthodox Churches. ISPCK. ISBN 9788172144876.

- O'Connor, Daniel William (2019). "Saint Peter the Apostle". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. p. 5. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- "Syriac Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch and All the East | Christianity". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Hilliard, Alison; Bailey, Betty (1999). Living Stones Pilgrimage. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9780826422491.

- Taylor 2014, p. 67.

- "Saint James apostle, the Lord's brother". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Markessini, Joan (2012). Around the World of Orthodox Christianity - Five Hundred Million Strong: The Unifying Aesthetic Beauty. Dorrance Publishing. ISBN 9781434914866.

- "The Hidden Pearl: The Syrian Orthodox Church and Its Ancient Aramaic Heritage". Trans World Film Italia. 19 March 2018. Retrieved 19 March 2018 – via Google Books.

- Lukenbill, W. Bernard (2012). Research in Information Studies: A Cultural and Social Approach. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 9781469179612.

- Atiya, Aziz Suryal (1968). A History of Eastern Christianity. Methuen.

- Minahan & Greenwood Press (Westport) 2002, p. 205-209.

- Grabar et al. 2001, p. 227.

- "Syrian Orthodox Church - Full record view - Libraries Australia Search". librariesaustralia.nla.gov.au.

- Donabed & Mako 2009, p. 90.

- Hämmerli & Mayer 2016, "Suryoye as a Social Category in the Homeland"

- Hengel 2004, p. 331.

- Taylor 2014, p. 201; Romeny 2005

- Donabed & Mako 2009, p. 77.

- Smith 1863, p. 73.

- Barratt, Peter J. H. (2014). Absentis: St Peter, the Disputed Site of His Burial Place and the Apostolic Succession. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 9781493168392.

- Gould, Sabine Baring (1872). The lives of the saints. 12 vols. [in 15]. p. 365.

Patriarchate of Antioch in AD 37.

- "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Evodius". www.newadvent.org.

- Elwell & Comfort 2001, pp. 266, 828.

- "Theophilus of Antioch (Roberts-Donaldson)". www.earlychristianwritings.com.

- Eduard Syndicus; Early Christian Art; p. 73; Burns & Oates, London, 1962

- Sellers, Robert Victor (1927). "Eustathius of Antioch and His Place in the History of Early Christian Doctrine".

- Stillingfleet, Edward (1685). Origines Britannicæ [i.e., Britannicae], Or, The Antiquities of the British Churches: With a Preface Concerning Some Pretended Antiquities Relating to Britain, in Vindication of the Bishop of St. Asaph. M. Flesher.

- Gardner, Rev James (1858). The Faiths of the World: An Account of All Religions and Religious Sects, Their Doctrines, Rites, Ceremonies, and Customs. A. Fullarton & Company. p. 403.

- General History of the Christian Religion and Church. Crocker & Brewster. 1855.

- Joseph, John (1983). Muslim-Christian Relations and Inter-Christian Rivalries in the Middle East: The Case of the Jacobites in an Age of Transition. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780873956000.

- Wordsworth, Christopher (1881). A Church History to the Council of Nicaea, A.D. 325. Rivingtons. p. 7.

Antioch First Council of Nicaea (325).

- Ecclesiastical History: A History of the Church in 5 Books from A.D.322 to the Death of Theodore of Mopsuestia, A.D.427 by Theodoretus Bishop of Cyrus a New Tr...with a Memoir of the Author... Greek ecclesiastical historians of the first 6 centuries. Bagster & sons. 1844. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Chaillot, Christine. The Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch and All the East. Geneva: Inter-Orthodox Dialogue, 1988.

- "Wilhelm Baum, Dietmar W. Winkler, The Church of the East: A Concise History (Routledge 2003), pp. 3 and 30" (PDF).

- Neale 2008, p. 202.

- "Flavian II of Antioch ; Biography, History, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Menze, Volker L. (2008). Justinian and the Making of the Syrian Orthodox Church. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780191560095.

- "Severus of Antioch Greek theologian". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Honigmann, Ernest (1947). "THE PATRIARCHATE OF ANTIOCH: A Revision of Le Quien and the Notitia Antiochena". Traditio. 5: 135–161. doi:10.1017/S0362152900013544. JSTOR 27830138.

- Jugie, Martin (1910). J. Lebon. Le monophysisme sévérien. Étude historique, littéraire et théologique de la résistance monophysite au concile de Chalcédoine jusqu'à la constitution de l'Église jacobite. pp. 368–369.

- Loetscher 1977, p. 82.

- Thomas 2001, p. 47.

- van Ginkel et al. 2005, p. 98.

- Markessini 2012, p. 31.

- Saint-Laurent 2015, p. 131.

- Saint-Laurent 2015, p. 103, 106.

- Saint-Laurent 2015, p. 136.

- Trimingham, J. Spencer (1990). Christianity Among the Arabs in Pre-Islamic Times. Stacey Publishing. ISBN 9781900988681.

- Ciggaar & Metcalf 2006, p. 108.

- Ciggaar & Metcalf 2006, p. 123.

- Ciggaar & Metcalf 2006, pp. 123–124.

- Benjamin Arbel (15 April 2013). Intercultural Contacts in the Medieval Mediterranean: Studies in Honour of David Jacoby. Routledge. pp. 69–. ISBN 978-1-135-78195-8.

- Masters 2004, p. 45.

- Dale A. Johnson. Living as a Syriac Palimpsest. Lulu.com. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-0-557-40255-7.

- Joseph 1983, p. 40.

- Joseph 1983, p. 41.

- "Oriens christianus : Hefte für die Kunde des christlichen Orients : Gesamtregister für die Bände 1(1901) bis 70(1986)" (in German). O. Harrassowitz. 2005.

- Jongerden & Verheij 2012, p. 21.

- Taylor 2014, p. 87.

- Sargon & Ninos Donabed (2010). Assyrians of Eastern Massachusetts. pp. 1–38.

- Sargon & Ninos Donabed (2010). Assyrians of Eastern Massachusetts. pp. 77–78.

- Peter C. Phan (21 January 2011). Christianities in Asia. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 251–. ISBN 978-1-4443-9260-9.

- Tozman & Tyndall 2012, p. 9.

- Jongerden & Verheij 2012, p. 225.

- Jongerden & Verheij 2012, p. 222.

- Jongerden & Verheij 2012, p. 223.

- Hage, Wolfgang (2007). Das orientalische Christentum (in German). Kohlhammer Verlag. ISBN 9783170176683.

- Hunter 2014, p. 549.

- Kevorkian 2011.

- Gaunt, David. Massacres, Resistance, Protectors: Muslim-Christian Relations in Eastern Anatolia during World War I. Piscataway, N.J.: Gorgias Press, 2006, pp. 433–436

- Parry 2010, p. 259.

- Michael Angold (17 August 2006). The Cambridge History of Christianity: Volume 5, Eastern Christianity. Cambridge University Press. pp. 513–. ISBN 978-0-521-81113-2.

- Joseph 1983, p. 110.

- Sobornost. 28–30. 2006. p. 21.

- "Patriarchal Encyclical: Permitting additions to Diptychs in Malankara - Oct 20, 1987". sor.cua.edu.

- "Melkite :: Patriarch". www.melkitepat.org.

- "With Wisdom and Courage, New Syriac Orthodox Patriarch Reaffirms the Church's Commitment to Syria Duke Religious Studies". religiousstudies.duke.edu.

- "Definition of BISHOP". www.merriam-webster.com.

- Tang, Li; Winkler, Dietmar W. (2013). From the Oxus River to the Chinese Shores: Studies on East Syriac Christianity in China and Central Asia. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 9783643903297.

- Kollanoor, Greger. The Office of the Deaconess in Orthodox Churches1 -A Historical Analysis.

- Wainwright, Geoffrey (2006). The Oxford History of Christian Worship. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 9780195138863.

- Brock, Sebastian P. The Bible in Syriac Bible. Kottayam: SEERI.

- Esomba, Steve. THE BOOK OF LIFE, KNOWLEDGE AND CONFIDENCE. Lulu.com. ISBN 9781471734632.

- Holy Bible: Matthew 16:19

- Aydin, Mor Polycarpus Augin (3 July 2018). "The Syriac tradition of the work of the Holy Spirit in the Church to make it One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic". International Journal for the Study of the Christian Church. Informa UK Limited. 18 (2–3): 124–131. doi:10.1080/1474225x.2018.1516428. ISSN 1474-225X.

- Butler, Alban (1821). The lives of the fathers, martyrs, and other principal saints.

- "CNEWA - The Syrian Orthodox Church". www.cnewa.org.

- O'Mahony & Loosley 2009, p. 4.

- Kurian & Nelson 2001, p. 8905.

- The Primacy of the Apostolic See, and the Authority of General Councils Vindicated. In a Series of Letters to the Rt. Rev. J. H. Hopkins. 1838.

- Benni 1871, p. 93.

- Weninger 2012, p. 697.

- Jastrow, Otto (1985). "Mlaḥsô: An Unknown Neo-Aramaic Language of Turkey". Journal of Semitic Studies. 30 (2): 265–270. doi:10.1093/jss/xxx.2.265.

- Joseph 1983, p. 22.

- "City Youth Learn Dying Language, Preserve It". The New Indian Express. 9 May 2016. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- Suriyani Malayalam, Nasrani Foundation

- "A sacred language is vanishing from State". The Hindu. 11 August 2008.

- Radhakrishnan, M. G. (4 August 1997). "Tiny village in Kerala one of the last bastions of Syriac in the world". India Today.

- "Surayt-Aramaic Online Project". Morephrem Monastery – Monastery Morephrem Website.

- "v. 1 n. 1 (2013): Anais do I Simpósio Nacional de Teologia Oriental Simpósio Internacional de Teologia Oriental". fasbam.edu.br.

- Patrologia syriaca: complectens opera omnia ss. patrum, doctorum scriptorumque catholicorum, quibus accedunt aliorum acatholicorum auctorum scripta quae ad res ecclesiasticas pertinent, quotquot syriace supersunt, secundum codices praesertim, londinenses, parisienses, vaticanos accurante R. Graffin ... Firmin-Didot et socii. 1926.

- The Oxford selection of Psalms and hymns, for the use of parish churches 1857, p. 89.

- Jarjour 2018, p. 236.

- Syrian Orthodox Church (2005). The Book of Common Prayer of the Syrian Church. Gorgias Press. ISBN 9781593330330.

- Rajan, Kannanayakal Mani (1991). Queen of the Sacraments: A Treatise on the Liturgy of the Holy Mass as Celebrated in the Syrian Orthodox Church. St. Mary's Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church.

Queen of the Sacraments Syriac Orthodox Church.

- Fahlbusch et al. 2008, p. 284.

- "TRC exhibition proposal: Faith and Attire. Vestments and embroidery within the Syriac Orthodox Church". www.trc-leiden.nl.

- Detailed explanation of vestments of Syriac Orthodox Church http://sor.cua.edu/Vestments/index.html

- Heilbrunn Timeline, Art History. "Batrashil". www.metmuseum.org. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Parry, Ken (2010). The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444333619.

- Gall, Timothy L. (ed). Worldmark Encyclopedia of Culture & Daily Life: Vol. 3 – Asia & Oceania. Cleveland, OH: Eastword Publications Development (1998); pg. 720–721.

- "The Syriac Orthodox Church Today". sor.cua.edu.

- "Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch - Dictionary definition of Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch - Encyclopedia.com: FREE online dictionary". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- "Syrian Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch and All the East — World Council of Churches". www.oikoumene.org. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- "Reclaiming Syriac heritage: A village in Turkey finds its voice". america.aljazeera.com.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Refworld – World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples – Turkey : Syriacs". Refworld. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- "Adherents.com". Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Taft, Robert F.; Affairs, Catholic Church National Conference of Catholic Bishops Bishops' Committee for Ecumenical and Interreligious (1986). The Oriental Orthodox Churches in the United States. United States Catholic Conference.

- Kiraz 2019.

- "Our Archbishop". Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch. 1 November 2016.

- Gasgous, S. (10 May 2016). "Appointment of Dionysius Jean Kawak". Sts. Peter and Paul Syriac Orthothox Church.

- "Archbishop Clemis Eugene Kaplan, Member of the Suryoyo Assyrian Hall of the Shame". www.bethsuryoyo.com.

- "Our church worldwide". St. Barsaumo Syriac Orthodox Church.

- Hager, Anna (3 July 2019). "The emergence of a Syriac Orthodox Mayan Church in Guatemala". International Journal of Latin American Religions. 3 (2): 370–389. doi:10.1007/s41603-019-00083-1. ISSN 2509-9965.

- "NOTICIAS DE MARZO 2012". www.icergua.org.

- "Orthodoxy in Guatemala". orthodox-institute.org.

- "Yacoub Eduardo Aguirre Oestmann - Names - Orthodoxia". www.orthodoxia.ch.

- "New Archbishop for Syriac Orthodox Church Enthroned in Argentina". News Orthodoxy Cognate PAGE. 10 April 2013.

- "Igreja Sirian Ortodoxa de Antioquia no Brasil". Igreja Sirian Ortodoxa de Antioquia no Brasil (in Portuguese).

- "Kiliseler - Manastırlar". mardin.ktb.gov.tr.

- "İstanbul - Ankara Süryani Ortodoks Metropolitliği". www.suryanikadim.org.

- "King receives Patriarch of Antioch and head of Syriac Orthodox Church". Jordan Times. 10 April 2019.

- Berg, Heleen Murre-van den. A Center of Transnational Syriac Orthodoxy: St. Mark's Convent in Jerusalem.

- "Consecration of Archbishop Patriarchal Vicar for Jerusalem". Malankara Archdiocese of the Syriac Church in North America. 10 April 2019. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- Curta & Holt 2016, p. 336.

- Journal of Kerala Studies. University of Kerala. 2010.

- Congress, Indian History (1959). Proceedings.

- Neill 2002, p. 251–252.

- "The Constitution of the Malankara Orthodox Church". mosc.in.

- Swiderski 1988a, p. 83.

- Sharma & Sharma 2004, p. 12.

- Whitehouse 1873, p. 125.

- "Valiapally, St. Mary's Knanaya Church, Pilgrim Centre, Kottayam, Kerala, India Kerala Tourism". www.keralatourism.org.

- Thomas, Anthony Korah (1993). The Christians of Kerala: A Brief Profile of All Major Churches. A.K. Thomas.

- "Ministry Of Corporate Affairs - societiesregistrationact". www.mca.gov.in.

- "പൗരസ്ത്യ സുവിശേഷ സമാജം ജനറൽ കൺവൻഷൻ തുടങ്ങി". ManoramaOnline.

- "Missionary Training Institute,Mission centres-The Evangelistic Association of the East,EAE,Perumbavoor,Kerala,India". eaepbr.org.

- Mayer, Dr Jean-François; Hämmerli, Ms Maria (2014). Orthodox Identities in Western Europe: Migration, Settlement and Innovation. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 9781472439314.

- Atto 2011.

- Brock et al. 2011.

- "Reception in the honor of His Holiness in Brussels". Syrian Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch. 7 September 2017.

- "The Holy Virgin Mary Church, Montfermeil, France". sor.cua.edu.

- "Warburg, Syrisch-orthodoxes Kloster - Klosterorte - Klöster - Kulturland Kreis Höxter". www.kulturland.org.

- "Duizenden Syrisch-Orthodoxen vieren Pasen in Glane". RTV Oost (in Dutch).

- "LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL NOTICE PAPER NSW" (PDF). www.parliament.nsw.gov.au.

- "HE Archbishop Mor Malatius Malki thank you letter to ACM Australian Coptic Movement (ACM)". www.auscma.com.

- "Home St Peter's". stpeters.

- "Orthodox Christian Educational Institutions (OCEI) - Orthodoxy Cognate PAGE - Society". Orthodoxy Cognate PAGE - Society.

- "Christian Education". Syrian Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch. 22 February 2015.

- "Antioch Syrian University". asu.edu.sy.

- "Despite adversities, Antioch Syrian University opens doors of hope — World Council of Churches".

- From the common declaration of Pope John Paul II and Patriarch Ignatius Zakka I Iwas, 23 June 1984

- "Pope, Orthodox patriarch express commitment for unity". National Catholic Reporter. 19 June 2015.

- "His Holiness Patriarch Kirill meets with Patriarch of the Syriac Orthodox Church | The Russian Orthodox Church".

Bibliography

Books

- Ahmet Taşğın; Eyyüp Tanrıverdi; Canan Seyfeli (2005). Süryaniler ve süryanilik (in Turkish). Orient. ISBN 978-975-98974-8-2.

- Atto, N. (2011). Hostages in the Homeland, Orphans in the Diaspora: Identity Discourses Among the Assyrian/Syriac Elites in the European Diaspora. LUP Dissertaties Series. Leiden University Press. ISBN 978-90-8728-148-9. Retrieved 25 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Aziz Günel (1970). Türk Süryaniler tarihi (in Turkish). Yazan.

- Bardakci, M.; Freyberg-Inan, A.; Giesel, C.; Leisse, O. (2017). Religious Minorities in Turkey: Alevi, Armenians, and Syriacs and the Struggle to Desecuritize Religious Freedom. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-1-137-27026-9. Retrieved 25 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ecclesiastical History: A History of the Church in 5 Books from A.D.322 to the Death of Theodore of Mopsuestia, A.D.427 by Theodoretus Bishop of Cyrus a New Tr...with a Memoir of the Author... Greek ecclesiastical historians of the first 6 centuries. Bagster & sons. 1844. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Benni, C.B. (1871). The Tradition of the Syriac Church of Antioch, Concerning the Primacy and the Prerogatives of St. Peter and of His Successors the Roman Pontiffs. Burns, Oates. Retrieved 25 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1992). Studies in Syriac Christianity: History, Literature, and Theology. Aldershot: Variorum. ISBN 9780860783053.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1996). Syriac Studies: A Classified Bibliography, 1960-1990. Kaslik: Parole de l'Orient.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1997). A Brief Outline of Syriac Literature. Kottayam: St. Ephrem Ecumenical Research Institute.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brock, S.P.; Taylor, D.G.K. (2001). The Hidden Pearl: At the turn of the third millennium ; the Syrian Orthodox witness. The Hidden Pearl: The Syrian Orthodox Church and Its Ancient Aramaic Heritage. Trans World Film Italia. Retrieved 25 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2006). Fire from Heaven: Studies in Syriac Theology and Liturgy. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 9780754659082.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brock, S.P.; Kiraz, G.; Gorgias Press; Butts, A.M.; Beth Mardutho--The Syriac Institute; Van Rompay, L. (2011). Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage. Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-59333-714-8. Retrieved 25 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ciggaar, Krijna Nelly; Metcalf, David Michael (2006). East and West in the Medieval Eastern Mediterranean: Antioch from the Byzantine reconquest until the end of the Crusader principality. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-90-429-1735-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Curta, F.; Holt, A. (2016). Great Events in Religion: An Encyclopedia of Pivotal Events in Religious History [3 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-566-4. Retrieved 25 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Elwell, Walter; Comfort, Philip Wesley (2001), Tyndale Bible Dictionary, Tyndale House Publishers, ISBN 0-8423-7089-7

- Fahlbusch, E.; Bromiley, G.W.; Lochman, J.M.; Mbiti, J.; Pelikan, J. (2008). The Encyclodedia of Christianity. The Encyclopedia of Christianity. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8028-2417-2. Retrieved 25 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gabriyel Akyüz (2001). Osmanlı Devleti'nde Süryani Kilisesi: Osmanlı padişahları tarafından Süryani Kilisesi'nin ruhani liderlerine gönderilen fermanlar (in Turkish). Mardin Kırklar Kilisesi. ISBN 978-975-8233-09-0.

- Grabar, G.W.B.P.R.L.B.O.; Bowersock, G.W.; Brown, P.; Brown, P.R.L.; Grabar, O.; Caseau, B.; Cameron, A.; Chadwick, H.; Fowden, G.; Geary, P.J. (2001). Interpreting Late Antiquity: Essays on the Postclassical World. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00598-3. Retrieved 1 November 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hämmerli, Maria; Mayer, Jean-François (2016). Orthodox Identities in Western Europe: Migration, Settlement and Innovation. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-08490-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hengel, M. (2004). Studies in Early Christology. Academic Paperback Series. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-0-567-04280-4. Retrieved 1 November 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hunter, Erica C. D. (2014). "The Syrian Orthodox Church". In Leustean, Lucian N. (ed.). Eastern Christianity and Politics in the Twenty-First Century. Routledge. pp. 541–562. ISBN 978-1-317-81866-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jarjour, T. (2018). Sense and Sadness: Syriac Chant in Aleppo. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-063528-2. Retrieved 25 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jongerden, Joost; Verheij, Jelle (2012). Social Relations in Ottoman Diyarbekir, 1870-1915. BRILL. pp. 222–. ISBN 978-90-04-22518-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Joseph, John (1983). Muslim-Christian Relations and Inter-Christian Rivalries in the Middle East: The Case of the Jacobites in an Age of Transition. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-87395-600-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kevorkian, Raymond (2011). The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. I.B.Tauris. pp. 91, 94, 365, 366, 368, 371–379, 887, 901. ISBN 978-0-85773-020-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kiraz, G.A. (2019). The Syriac Orthodox in North America (1895-1995): A Short History. Gorgias handbooks. Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-4632-4037-0. Retrieved 25 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kurian, G.; Nelson, T. (2001). Nelson's Dictionary of Christianity: The Authoritative Resource on the Christian World. Thomas Nelson. ISBN 978-1-4185-3981-8. Retrieved 25 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kurian, George (2011). "Syriac Orthodox Church". The encyclopedia of Christian civilization. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub. Ltd. p. 2304. ISBN 978-1-4051-5762-9. OCLC 227191238.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Loetscher, L.A. (1977). The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge: Embracing Biblical, Doctrinal, and Practical Theology and Biblical, Theological, and Eclesiastical Biography from the Earliest Times to the Present Day, Based on the 3d Ed. of the Realencyklopädie Founded by J. J. Herzog, and Edited by Albert Hauck, Prepared by More Than Six Hundred Scholars and Specialists Under the Supervision of Samuel Macauley Jackson (editor-in-chief) with the Assistance of Charles Colebrook Sherman and George William Gilmore (associate Editors) ... [et. Al.]. Baker. ISBN 978-0-8010-7947-4. Retrieved 25 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Markessini, J. (2012). Around the World of Orthodox Christianity - Five Hundred Million Strong: The Unifying Aesthetic Beauty. Dorrance Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-4349-1486-6. Retrieved 25 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Masters, B. (2004). Christians and Jews in the Ottoman Arab World: The Roots of Sectarianism. Cambridge Studies in Islamic Civilization. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00582-1. Retrieved 6 November 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Meinardus, O.F.A. (1964). The Syrian Jacobites in the Holy City. Almqvist & Wiksells Boktryckerl AB. Retrieved 6 November 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Menze, Volker L. (2008). Justinian and the Making of the Syrian Orthodox Church. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-156009-5.

- Meyendorff, John (1989). Imperial unity and Christian divisions: The Church 450–680 A.D. The Church in history. 2. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 9780881410556.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Minahan, J.; Greenwood Press (Westport), Conn.) (2002). Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: A-C. Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-32109-2. Retrieved 1 November 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Neale, J.M. (2008). A History of the Holy Eastern Church: The Patriarchate of Antioch: The Patriarchate of Antioch. Wipf & Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-60608-330-7. Retrieved 25 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Neill, S. (2002). A History of Christianity in India: 1707-1858. History of Christianity in India / Stephen Neill. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89332-9. Retrieved 25 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Mahony, A.; Loosley, E. (2009). Eastern Christianity in the Modern Middle East. Culture and Civilization in the Middle East. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-135-19371-3. Retrieved 25 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Parry, Ken (2010). The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-3361-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pohl, W.; Gantner, C.; Payne, R. (2016). Visions of Community in the Post-Roman World: The West, Byzantium and the Islamic World, 300â€"1100. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-00136-2. Retrieved 25 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Saint-Laurent, Jeanne-Nicole Mellon (2015). Missionary Stories and the Formation of the Syriac Churches. University of California Press. pp. 94–. ISBN 978-0-520-96058-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sharma, S.K.; Sharma, U. (2004). Cultural and Religious Heritage of India: Christianity. Cultural and Religious Heritage of India. Mittal Publications. ISBN 978-81-7099-959-1. Retrieved 25 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, W. (1863). A Dictionary of the Bible: Comprising Its Antiquities, Biography, Geography, and Natural History. A Dictionary of the Bible: Comprising Its Antiquities, Biography, and Natural History. J. Murray. p. 73. Retrieved 25 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Taylor, William (2014). Narratives of Identity: The Syrian Orthodox Church and the Church of England 1895-1914. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-6946-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- The Oxford selection of Psalms and hymns, for the use of parish churches. 1857. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Thomas, D.R. (2001). Syrian Christians Under Islam: The First Thousand Years. Biblical Studies and Religious Studies. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-12055-6. Retrieved 25 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tozman, Markus K.; Tyndall, Andrea (2012). The Slow Disappearance of the Syriacs from Turkey and of the Grounds of the Mor Gabriel Monastery. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3-643-90268-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- van Ginkel, J.J.; Den Berg, H.M.V.; Ginkel, J.J.; van Ginkel, J.; den Berg, H.L.M.; van Lint, T.M.; van Lint, T. (2005). Redefining Christian Identity: Cultural Interaction in the Middle East Since the Rise of Islam. Orientalia Lovaniensia analecta. Uitgeverij Peeters en Departement Oosterse Studies. ISBN 978-90-429-1418-6. Retrieved 27 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Weninger, Stefan (2012). The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-025158-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Whitehouse, T. (1873). Lingerings of light in a dark land: researches into the Syrian church of Malabar. Retrieved 25 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Yakup Bilge (1991). Süryanilerin kökeni ve Türkiyeli Süryaniler (in Turkish). Y. Bilge.

Journals

- Aydin, Mor Polycarpus Augin (3 July 2018). "The Syriac tradition of the work of the Holy Spirit in the Church to make it One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic". International Journal for the Study of the Christian Church. Informa UK Limited. 18 (2–3): 124–131. doi:10.1080/1474225x.2018.1516428. ISSN 1474-225X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Donabed, Sargon; Mako, Shamiran (2009). "Ethno-Cultural and Religious Identity of Syrian Orthodox Christians". Chronos: Revue d'Histoire de l'Université de Balaman. Elsevier BV. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1541167. ISSN 1556-5068.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Janin, Raymond (1919). "Le rite syrien et les Églises syriennes". Revue des études byzantines (in French). 18 (115): 321–341. doi:10.3406/rebyz.1919.4214.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Romeny, Bas Ter Haar (2005). "From religious association to ethnic community: a research project on identity formation among the Syrian orthodox under muslim rule". Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations. Informa UK Limited. 16 (4): 377–399. doi:10.1080/09596410500250248. ISSN 0959-6410.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Swiderski, Richard Michael (1988). "Northists and Southists: A Folklore of Kerala Christians". Asian Folklore Studies. Nanzan University. 47 (1): 73–92. doi:10.2307/1178253. JSTOR 1178253.

Further reading

- Armbruster, Heidi (2002), Homes in crisis: Syrian orthodox Christians in Turkey and Germany, pp. 17–33

- Millar, Fergus (2013), "The Evolution of the Syrian Orthodox Church in the Pre-Islamic Period: From Greek to Syriac?", Journal of Early Christian Studies, 21 (1): 43–92, doi:10.1353/earl.2013.0002

- Öktem, Kerem (2004), "Incorporating the time and space of the ethnic 'other': nationalism and space in Southeast Turkey in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries", Nations and Nationalism, 10 (4): 559–578, doi:10.1111/j.1354-5078.2004.00182.x

- Palmer, Andrew (1991), "The History of the Syrian Orthodox in Jerusalem", Oriens Christianus (75): 16–43

- Sato, Noriko (2005), "Selective Amnesia: Memory and History of the Urfalli Syrian Orthodox Christians", Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power 12.3: 315–333

- Snelders, Bas (2010), Identity and Christian-Muslim interaction: medieval art of the Syrian Orthodox from the Mosul area, Leiden Institute for Religious Studies, Faculty of the Humanities

- Van Ginkel, Jan J. (2006), "The perception and presentation of the Arab conquest in Syriac Historiography: How did the changing social position of the Syrian orthodox community influence the account of their historiographers?", The Encounter of Eastern Christianity with Early Islam, Brill, pp. 171–184

- Weltecke, Dorothea (2003), Contacts between Syriac Orthodox and Latin Military Orders

- Weltecke, Dorothea (2006), The Syriac Orthodox in the principality of Antioch during the Crusader period

- Wozniak, Marta (2015). "From religious to ethno-religious: Identity change among Assyrians/Syriacs in Sweden" (PDF). Joint Sessions of Workshops organized by the European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR). ECPR.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Ecumenical relations with the Catholic Church

- Pope Benedict XIV, Allatae Sunt (On the observance of Oriental Rites), Encyclical, 1755

- Addresses of Pope Paul VI and His Holiness Mar Ignatius Jacob III, 1971

- Common Declaration of Pope John Paul II and His Holiness Mar Ignatius Zakka I Iwas, 1984

- Address of John Paul II on Occasion of the Visit to the Catholicos of the Malankarese Syrian Orthodox Church, 1986

- Address of His Holiness Pope Francis to His Holiness Mor Ignatius Aphrem II Syriac orthodox patriarch of Antioch and all the East, 19 June 2015

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Syriac Orthodox Church. |

- Syriac Orthodox Patriarchate (Official website)

- Department of Syriac Studies

Media

- Syriac religious TV channel of Syriac Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch

- Syriac Liturgy description and photos

- Syriac Music Online

Relating to Syriac Orthodox Church

Relating to Malankara Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church

_(40443308951).jpg)

%2C_overlooking_Bashiqa_and_Bartella%2C_between_the_Kurdistan_Region_and_Iraq_22.jpg)

.jpg)