Amorites

The Amorites (/ˈæməˌraɪts/; Sumerian 𒈥𒌅 MAR.TU; Akkadian Amurrūm or Tidnum; Egyptian Amar; Hebrew: אמורי ʼĔmōrī; Ancient Greek: Ἀμορραῖοι) were an ancient Semitic-speaking people[1] from Syria who also occupied large parts of southern Mesopotamia from the 21st century BC to the end of the 17th century BC, where they established several prominent city states in existing locations, such as Isin, Larsa and later notably Babylon, which was raised from a small town to an independent state and a major city. The term Amurru in Akkadian and Sumerian texts refers to both them and to their principal deity.

The Amorites are also mentioned in the Bible as inhabitants of Canaan both before and after the conquest of the land under Joshua.

Origin

In the earliest Sumerian sources concerning the Amorites, beginning about 2400 BC, the land of the Amorites ("the Mar.tu land") is associated not with Mesopotamia but with the lands to the west of the Euphrates, including Canaan and what was to become Syria by the 3rd century BC, then known as The land of the Amurru, and later as Aram and Eber-Nari.

They appear as an uncivilized and nomadic people in early Mesopotamian writings from Sumer, Akkad, and Assyria, especially connected with the mountainous region now called Jebel Bishri in northern Syria called the "mountain of the Amorites". The ethnic terms Mar.tu ("Westerners"), Amurru (suggested in 2007 to be derived from aburru, "pasture") and Amor were used for them in Sumerian, Akkadian,[2] and Ancient Egyptian respectively.[3] From the 21st century BC, possibly triggered by a long major drought starting about 2200 BC, a large-scale migration of Amorite tribes infiltrated southern Mesopotamia. They were one of the instruments of the downfall of the Third Dynasty of Ur, and Amorite dynasties not only usurped the long-extant native city-states such as Isin, Larsa, Eshnunna, and Kish, but also established new ones, the most famous of which was to become Babylon, although it was initially a minor insignificant state.

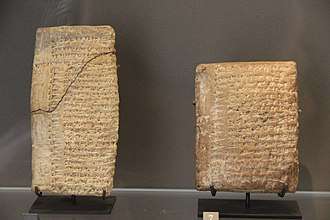

Known Amorites wrote in a dialect of Akkadian found on tablets at Mari dating from 1800–1750 BC. Since the language shows northwest Semitic forms, words and constructions, the Amorite language is a Northwest Semitic language, and possibly one of the Canaanite languages. The main sources for the extremely limited knowledge about Amorite are the proper names, not Akkadian in style, that are preserved in such texts. The Akkadian language of the native Semitic states, cities and polities of Mesopotamia (Akkad, Assyria, Babylonia, Isin, Kish, Larsa, Ur, Nippur, Uruk, Eridu, Adab, Akshak, Eshnunna, Nuzi, Ekallatum, etc.), was from the east Semitic, as was the Eblaite of the northern Levant.

History

In the earliest Sumerian texts, all western lands beyond the Euphrates, including the modern Levant, were known as "the land of the mar.tu (Amorites)". The term appears in Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, which describes it in the time of Enmerkar as one of the regions inhabited by speakers of a different language. Another text known as Lugalbanda and the Anzud bird describes how, 50 years into Enmerkar's reign, the Martu people arose in Sumer and Akkad (southern Mesopotamia), necessitating the building of a wall to protect Uruk.

There are also sparse mentions in tablets from the East Semitic-speaking kingdom of Ebla, dating from 2500 BC to the destruction of the city c. 2250 BC: from the perspective of the Eblaites, the Amorites were a rural group living in the narrow basin of the middle and upper Euphrates in northern Syria.[4] For the Akkadian kings of central Mesopotamia Mar.tu was one of the "Four Quarters" surrounding Akkad, along with Subartu/Assyria, Sumer, and Elam. Naram-Sin of Akkad records successful campaigns against them in northern Syria c. 2240 BC, and his successor, Shar-Kali-Sharri, followed suit.

By the time of the last days of the Third Dynasty of Ur, the immigrating Amorites had become such a force that kings such as Shu-Sin were obliged to construct a 270-kilometre (170 mi) wall from the Tigris to the Euphrates to hold them off.[5] The Amorites appear as nomadic tribes under chiefs, who forced themselves into lands they needed to graze their herds. Some of the Akkadian literature of this era speaks disparagingly of the Amorites and implies that the Akkadian- and Sumerian-speakers of Mesopotamia viewed their nomadic and primitive way of life with disgust and contempt:

The MAR.TU who know no grain.... The MAR.TU who know no house nor town, the boors of the mountains.... The MAR.TU who digs up truffles... who does not bend his knees (to cultivate the land), who eats raw meat, who has no house during his lifetime, who is not buried after death[.][6]

"They have prepared wheat and gú-nunuz (grain) as a confection, but an Amorite will eat it without even recognizing what it contains!"[7]

As the centralized structure of the Third Dynasty slowly collapsed, the component regions, such as Assyria in the north and the city-states of the south such as Isin, Larsa and Eshnunna, began to reassert their former independence, and the areas in southern Mesopotamia with Amorites were no exception. Elsewhere, the armies of Elam, in southern Iran, were attacking and weakening the empire, making it vulnerable.

.jpg)

Many Amorite chieftains in southern Mesopotamia aggressively took advantage of the failing empire to seize power for themselves. There was not an Amorite invasion of southern Mesopotamia as such, but Amorites ascended to power in many locations, especially during the reign of the last king of the Neo-Sumerian Empire, Ibbi-Sin. Leaders with Amorite names assumed power in various places, usurping native Akkadian rulers, including in Isin, Eshnunna and Larsa. The small town of Babylon, unimportant both politically and militarily, was raised to the status of a minor independent city-state, under Sumu-abum in 1894 BC.

The Elamites finally sacked Ur in c. 2004 BC. Some time later, the Old Assyrian Empire (c. 2050 – 1750 BC) became the most powerful entity in Mesopotamia immediately preceding the rise of the Amorite king Hammurabi of Babylon. The new Assyrian monarchic line was founded by c. 2050 BC; their kings repelled attempted Amorite incursions, and may have countered their influence in the south as well under Erishum I, Ilu-shuma and Sargon I. However, even Assyria eventually found its throne usurped by an Amorite in 1809 BC: the last two rulers of the Old Assyrian Empire period, Shamshi-Adad I and Ishme-Dagan, were Amorites who originated in Terqa (now in northeastern Syria).

There is a wide range of views regarding the Amorite homeland.[8] One extreme is the view that kur mar.tu/māt amurrim covered the whole area between the Euphrates and the Mediterranean Sea, the Arabian Peninsula included. The most common view is that the “homeland” of the Amorites was a limited area in central Syria identified with the mountainous region of Jebel Bishri.[9] Since the Amorite language is closely related to the better-studied Canaanite languages, both being branches of the Northwestern Semitic languages, as opposed to the South Semitic languages found in the Arabian Peninsula, they are usually considered native to the region around Syria and the Transjordan.

Effects on Mesopotamia

The rise of the Amorite kingdoms in Mesopotamia brought about deep and lasting repercussions in its political, social and economic structure, especially in southern Mesopotamia.

The division into kingdoms replaced the Babylonian city-states in southern Mesopotamia. Men, land and cattle ceased to belong physically to the gods or to the temples and the king. The new Amorite monarchs gave or let out for an indefinite period numerous parcels of royal or sacerdotal land, freed the inhabitants of several cities from taxes and forced labour, which seems to have encouraged a new society to emerge: a society of big farmers, free citizens and enterprising merchants, which was to last throughout the ages. The priest assumed the service of the gods and cared for the welfare of his subjects, but the economic life of the country was no longer exclusively (or almost exclusively) in their hands.

In general terms, Mesopotamian civilization survived the arrival of Amorites, as the indigenous Babylonian civilisation had survived the short period of Gutian dynasty of Sumer's domination of the south during the restless period after the fall of the Akkadian Empire that had preceded the rise of the Third Dynasty of Ur (the "Neo-Sumerian Empire"). The religious, ethical, technological, scientific and artistic directions in which Mesopotamia had been developing since the 4th millennium BC were not greatly affected by the Amorites' hegemony. They continued to worship the Sumero-Akkadian gods, and the older Sumerian myths and epic tales were piously copied, translated, or adapted, generally with only minor alterations. As for the scarce artistic production of the period, there is little to distinguish it from the preceding Ur III era.

The era of the Amorite kingdoms, c. 2000 – 1595 BC, is sometimes known as the "Amorite period" in Mesopotamian history. The principal Amorite dynasties arose in Mari, Yamhad, Qatna, fairly briefly in Assyria (under Shamshi-Adad I), Isin, Larsa and Babylon.

Babylon, originally a minor state at its founding in 1894 BC, became briefly the major power in the ancient world during the reign of Hammurabi in the first part of the 18th century BC, and it was from then that southern Mesopotamia came to be known as Babylonia, the north long before it evolved into Assyria.

Downfall

The era ended in northern Mesopotamia, with the defeat and expulsion of the Amorites and Amorite-dominated Babylonians from Assyria by Puzur-Sin and king Adasi between 1740 and 1735 BC, and in the far south, by the rise of the native Sealand Dynasty c. 1730 BC. The Amorites clung on in a once-more small and weak Babylon until the Hittite sack of Babylon (c. 1595 BC), which ended the Amorite presence, and brought new ethnic groups, particularly the Kassites, to the forefront in southern Mesopotamia. From the 15th century BC onward, the term Amurru is usually applied to the region extending north of Canaan as far as Kadesh on the Orontes River in northern Syria.[10]

After their expulsion from Mesopotamia, the Amorites of Syria came under the domination of first the Hittites and, from the 14th century BC, the Middle Assyrian Empire (1365–1050). They appear to have been displaced or absorbed by a new wave of semi-nomadic West Semitic-speaking peoples, known collectively as the Ahlamu during the Late Bronze Age collapse. The Arameans rose to be the prominent group amongst the Ahlamu, and from c. 1200 BC on, the Amorites disappeared from the pages of history. From then on, the region that they had inhabited became known as Aram ("Aramea") and Eber-Nari.

States

|

In the Levant:

|

In Mesopotamia:

|

Biblical Amorites

The term Amorites is used in the Bible to refer to certain highland mountaineers who inhabited the land of Canaan, described in Genesis as descendants of Canaan, the son of Ham (Gen. 10:16). They are described as a powerful people of great stature "like the height of the cedars" (Amos 2:9) who had occupied the land east and west of the Jordan. The height and strength mentioned in Amos 2:9 has led some Christian scholars, including Orville J. Nave, who wrote the Nave's Topical Bible, to refer to the Amorites as "giants".[11]

In Deuteronomy, the Amorite king, Og, was described as the last "of the remnant of the Rephaim" (Deut 3:11). The terms Amorite and Canaanite seem to be used more or less interchangeably, Canaan being more general and Amorite a specific component among the Canaanites who inhabited the land.

The Biblical Amorites seem to have originally occupied the region stretching from the heights west of the Dead Sea (Gen. 14:7) to Hebron (Gen. 13:8; Deut. 3:8; 4:46–48), embracing "all Gilead and all Bashan" (Deut. 3:10), with the Jordan valley on the east of the river (Deut. 4:49), the land of the "two kings of the Amorites". Sihon and Og (Deut. 31:4 and Joshua 2:10; 9:10). Both Sihon and Og were independent kings. The Amorites seem to have been linked to the Jerusalem region, and the Jebusites may have been a subgroup of them (Ezek. 16:3). The southern slopes of the mountains of Judea are called the "mount of the Amorites" (Deut. 1:7, 19, 20).

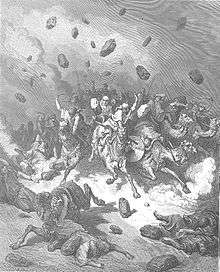

The Book of Joshua speaks of the five kings of the Amorites were first defeated with great slaughter by Joshua (Josh. 10:5). Then, more Amorite kings were defeated at the waters of Merom by Joshua (Josh. 11:8). It is mentioned that in the days of Samuel, there was peace between them and the Israelites (1 Sam. 7:14). The Gibeonites were said to be their descendants, being an offshoot of the Amorites who made a covenant with the Hebrews. When Saul later broke that vow and killed some of the Gibeonites, God sent a famine to Israel.

Indo-European hypothesis

The view that Amorites were fierce, tall nomads led to an anachronistic theory among some racialist writers in the 19th century that they were a tribe of "Aryan" warriors who at one point dominated the Israelites. Then, the evidence fitted then-current models of Indo-European migrations. The theory originated with Felix von Luschan, who later abandoned it.[12]

Houston Stewart Chamberlain claimed that King David and Jesus were both Aryans of Amorite extraction. The argument was repeated by the Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg.[13]

In reality, however, the Amorites certainly spoke exclusively a Semitic language, followed Semitic religions of the Near East and had distinctly Semitic personal names. Their origins were believed to have been the lands immediately to the west of Mesopotamia, in the Levant (modern Syria), and so they are regarded as one of the Semitic peoples.[14][15][16]

References

- "Amorite (people)". Encyclopædia Britannica online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- Issar, Arie S.; Zohar, Mattanyah (2013). "Dark Age, Renaissance, and Decay". Climate Change: Environment and History of the Near East (PDF). Springer Science and Business Media. p. 148.

- ibd, Mattanyah Zohar, "Climate Change Environment" 2007, p. 178

- Giorgio Bucellati, "Ebla and the Amorites", Eblaitica 3 (1992):83-104.

- William H. Stiebing Jr. Ancient Near Eastern History And Culture Longman: New York, 2003: 79

- E. Chiera, Sumerian Epics and Myths, Chicago, 1934, Nos.58 and 112.

- E. Chiera, Sumerian Texts of Varied Contents, Chicago, 1934, No. 3.

- Alfred Haldar, Who Were the Amorites (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1971), p. 7

- Minna Lönnqvist, Markus Törmä, Kenneth Lönnqvist and Milton Nunez, Jebel Bishri in Focus: Remote sensing, archaeological surveying, mapping and GIS studies of Jebel Bishri in central Syria by the Finnish project SYGIS. BAR International Series 2230. (Oxford: Archaeopress, 2011)

-

- Nave's Topical Bible: Amorites, Nave, Orville J., Retrieved:2013-03-14

- "Are the Jews a Race?" by Sigmund Feist in "Jews and Race: Writings on Identity and Difference, 1880-1940", edited by Mitchell Bryan Hart, UPNE, 2011, p. 88

- Hans Jonas, New York Review of Books, 1981

- Who Were the Amorites?, by Alfred Haldar, 1971, Brill Archive

- Semitic Studies, Volume 1, by Alan Kaye, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 1991, p.867

- The Semitic Languages, by Stefan Weninger, Walter de Gruyter, 23 Dec 2011, p.361

Bibliography

- E. Chiera, Sumerian Epics and Myths, Chicago, 1934, Nos.58 and 112;

- E. Chiera, Sumerian Texts of Varied Contents, Chicago, 1934, No.3.;

- H. Frankfort, AAO, pp. 54–8;

- F.R. Fraus, FWH, I (1954);

- G. Roux, Ancient Iraq, London, 1980.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amorites. |

- Amorites in the Jewish Encyclopedia

| Ancient Syria and Mesopotamia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syria | Northern Mesopotamia | Southern Mesopotamia | |||||||

| c. 3500–2350 BCE | Semitic nomads | Sumerian city-states | |||||||

| c. 2350–2200 BCE | Akkadian Empire | ||||||||

| c. 2200–2100 BCE | Gutians | ||||||||

| c. 2100–2000 BCE | Third Dynasty of Ur (Sumerian Renaissance) | ||||||||

| c. 2000–1800 BCE | Mari and other Amorite city-states | Old Assyrian Empire (Northern Akkadians) | Isin/Larsa and other Amorite city-states | ||||||

| c. 1800–1600 BCE | Old Hittite Kingdom | Old Babylonian Empire (Southern Akkadians) | |||||||

| c. 1600–1400 BCE | Mitanni (Hurrians) | Karduniaš (Kassites) | |||||||

| c. 1400–1200 BCE | Middle Hittite Kingdom | Middle Assyria | |||||||

| c. 1200–1150 BCE | Bronze Age Collapse ("Sea Peoples") | Arameans | |||||||

| c. 1150–911 BCE | Phoenicia | Neo-Hittite city-states |

Aram- Damascus |

Arameans | Middle Babylonia | Chal- de- ans | |||

| 911–729 BCE | Neo-Assyrian Empire | ||||||||

| 729–609 BCE | |||||||||

| 626–539 BCE | Neo-Babylonian Empire (Chaldeans) | ||||||||

| 539–331 BCE | Achaemenid Empire | ||||||||

| 336–301 BCE | Macedonian Empire (Ancient Greeks and Macedonians) | ||||||||

| 311–129 BCE | Seleucid Empire | ||||||||

| 129–63 BCE | Seleucid Empire | Parthian Empire | |||||||

| 63 BCE–243 CE | Roman Empire/Byzantine Empire (Syria) | ||||||||

| 243–636 CE | Sassanid Empire | ||||||||