Ulysses S. Grant

| Ulysses S. Grant | |

|---|---|

| |

| 18th President of the United States | |

|

In office March 4, 1869 – March 4, 1877 | |

| Vice President |

Schuyler Colfax (1869–1873) Henry Wilson (1873–1875) None (1875–1877) |

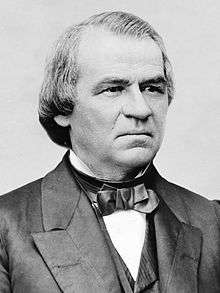

| Preceded by | Andrew Johnson |

| Succeeded by | Rutherford B. Hayes |

| United States Secretary of War Acting | |

|

In office August 12, 1867 – January 14, 1868 | |

| President | Andrew Johnson |

| Preceded by | Edwin Stanton |

| Succeeded by | Edwin Stanton |

| 6th Commanding General of the United States Army | |

|

In office March 9, 1864 – March 4, 1869 | |

| President |

Abraham Lincoln Andrew Johnson |

| Preceded by | Henry W. Halleck |

| Succeeded by | William Tecumseh Sherman |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Hiram Ulysses Grant April 27, 1822 Point Pleasant, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died |

July 23, 1885 (aged 63) Wilton, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place | Grant's Tomb, New York City, NY |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | Frederick, Ulysses Jr., Nellie, and Jesse |

| Parents |

Jesse Root Grant Hannah Simpson |

| Education | United States Military Academy (BS) |

| Signature |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service |

1839–1854 1861–1869 |

| Rank |

|

| Commands |

Company F, 4th Infantry 21st Illinois Infantry Regiment District of Southeast Missouri District of Cairo Army of the Tennessee Division of the Mississippi United States Army |

| Battles/wars |

|

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

American Civil War President of the United States

Post-Presidency

|

||

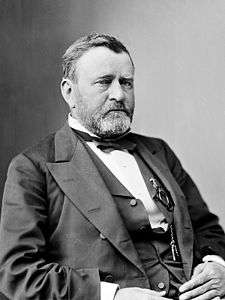

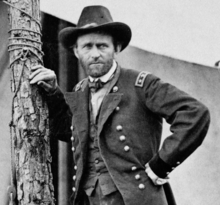

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant;[lower-alpha 1] April 27, 1822 – July 23, 1885) was the 18th President of the United States, Commanding General of the Army, soldier, international statesman, and author. During the American Civil War Grant led the Union Army to victory over the Confederacy with the supervision of President Abraham Lincoln. During the Reconstruction Era President Grant led the Republicans in their efforts to remove the vestiges of Confederate nationalism, racism, and slavery.

From early childhood in Ohio, Grant was a skilled equestrian who had a talent for taming horses. He graduated from West Point in 1843 and served with distinction in the Mexican–American War. Upon his return, Grant married Julia Dent, and together they had four children. In 1854, Grant abruptly resigned from the army. He and his family struggled financially in civilian life for seven years. When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Grant joined the Union Army and rapidly rose in rank to general. He won major battles at Shiloh and seized Vicksburg, Grant gained control of the Mississippi River and divided the Confederacy in two. In March 1864, after his victory at Chattanooga, President Lincoln promoted Grant to Lieutenant General, a rank previously reserved for George Washington. For over a year Grant's Army of the Potomac fought the Army of Northern Virginia led by Robert E. Lee in the Overland Campaign, and at Petersburg. On April 9, 1865, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox, and the war ended.

President Lincoln was assassinated on April 14, 1865. Grant continued to serve as General of the Army under the new president, Andrew Johnson. Grant was disillusioned by Johnson's conservative approach to Reconstruction, and drifted toward the "Radical" Republicans. Elected president in 1868, Grant stabilized the post-war national economy, created the Department of Justice, and prosecuted the Ku Klux Klan under the Force Acts. He appointed African-Americans and Jewish-Americans to prominent federal offices. In 1871, Grant created the first Civil Service Commission. The Democrats and Liberal Republicans united behind Grant's opponent in the presidential election of 1872, but Grant was handily re-elected. Grant's new Peace Policy for Native Americans had both successes and failures. Grant's administration successfully resolved the Alabama claims and the Virginius Affair, but Congress rejected his Dominican annexation initiative. Corruption charges and the Panic of 1873 plagued Grant's presidency.

After Grant left office in March 1877, he embarked on a two-and-a-half-year world tour that captured favorable global attention for him and the United States. In 1880, Grant was unsuccessful in obtaining the Republican presidential nomination for a third term. In the final year of his life, facing severe investment reversals and dying of throat cancer, he wrote his memoirs, which proved to be a major critical and financial success. At the time of his death, he was memorialized as a symbol of national unity.

Historical assessments of Grant's legacy have varied considerably over the years. Historians have hailed Grant's military genius, and his strategies are featured in military history textbooks. Grant's presidency has traditionally been criticized for multiple scandals and for his protection of his friends. Recent scholarship has recognized his achievements, and regarded him as an embattled president who performed a difficult job during Reconstruction. Although rankings of Presidents once rated his administration among the worst, modern appreciation for Grant's civil rights enforcement and diverse appointments has raised his historical reputation.

Early life and education

Hiram Ulysses Grant was born in Point Pleasant, Ohio, on April 27, 1822, to Jesse Root Grant, a tanner and merchant, and Hannah Grant (née Simpson).[2] His ancestors Matthew and Priscilla Grant arrived aboard the Mary and John at Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630.[3] Grant's great-grandfather fought in the French and Indian War, and his grandfather, Noah, served in the American Revolution at Bunker Hill.[4] Afterward, Noah settled in Pennsylvania and married Rachel Kelley, the daughter of an Irish pioneer.[5] Their son Jesse (Ulysses's father) was a Whig Party supporter and a fervent abolitionist.[6]

Jesse Grant moved to Point Pleasant in 1820 and found work as a foreman in a tannery.[7] He soon met his future wife, Hannah, and the two were married on June 24, 1821.[8] Ten months later Hannah gave birth to their first child, a son.[9] At a family gathering several weeks later the boy's name, Ulysses, was drawn from ballots placed in a hat. Wanting to honor his father-in-law, who had suggested Hiram, Jesse declared the boy to be Hiram Ulysses, though he would always refer to him as Ulysses.[10][lower-alpha 2]

In 1823, the family moved to Georgetown, Ohio, where five more siblings were born: Simpson, Clara, Orvil, Jennie, and Mary.[12] At the age of five, Ulysses began his formal education, starting at a subscription school and later in two private schools.[13] In the winter of 1836–1837, Grant was a student at Maysville Seminary, and in the autumn of 1838 he attended John Rankin's academy. In his youth, Grant developed an unusual ability to ride and manage horses.[14] Since Grant expressed a strong dislike for the tannery his father put his ability with horses to use by giving him work driving wagon loads of supplies and transporting people.[15] Unlike his siblings, Grant was not forced to attend church by his Methodist parents.[16][lower-alpha 3] For the rest of his life, he prayed privately and never officially joined any denomination.[17] To others, including late in life, his own son, Grant appeared to be an agnostic.[18] He inherited some of Hannah's Methodist piety and quiet nature.[19] Grant was largely apolitical before the war but wrote, "If I had ever had any political sympathies they would have been with the Whigs. I was raised in that school."[20]

Early military career and personal life

West Point and first assignment

Grant's father wrote to Representative Thomas L. Hamer requesting that he nominate Ulysses to the United States Military Academy (USMA) at West Point, New York. When a spot opened in March 1839, Hamer nominated the 16-year-old Grant.[21] He mistakenly wrote down "Ulysses S. Grant", which became his adopted name because West Point could not change the name of the appointee.[22][lower-alpha 4] Initially reluctant because of concerns about his academic ability, Grant entered the academy on July 1, 1839, as a cadet and trained there for four years.[25] His nickname became "Sam" among army colleagues since the initials "U.S." also stood for "Uncle Sam".[26]

Initially, Grant was indifferent to military life, but within a year he reexamined his desire to leave the academy and later wrote that "on the whole I like this place very much".[27] While at the Academy, his greatest interest was horses, and he earned a reputation as the "most proficient" horseman.[28] During the graduation ceremony, while riding York, a large and powerful horse that only Grant could manage well, he set a high-jump record that stood for 25 years.[29][lower-alpha 5] Seeking relief from military routine, he studied under Romantic artist Robert Walter Weir, producing nine surviving artworks.[31] He spent more time reading books from the library than his academic texts, frequently reading works by James Fenimore Cooper and others.[32] On Sundays, cadets were required to march to and attend services at the academy's church, a requirement that Grant disliked.[33] Quiet by nature, Grant established a few intimate friends among fellow cadets, including Frederick Tracy Dent and James Longstreet. He was inspired both by the Commandant, Captain Charles F. Smith and by General Winfield Scott, who visited the academy to review the cadets. Grant later wrote of the military life, "there is much to dislike, but more to like."[34]

Grant graduated on June 30, 1843, ranked 21st out of 39 alumni, and was promoted on July 1 to the rank brevet second lieutenant.[35] Small for his age at 17, he had entered the academy weighing only 117 pounds at five feet two inches tall; upon graduation four years later he had grown to a height of five feet seven inches.[36] Glad to leave the academy, he planned to resign his commission after his four-year term of duty.[37] Grant would later write to a friend that among the happiest days of his life was the day he left the presidency and the day he left the academy.[38] Despite his excellent horsemanship, he was not assigned to the cavalry, but to the 4th Infantry Regiment. Grant's first assignment took him to the Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis, Missouri.[39] Commanded by Colonel Stephen W. Kearny, the barracks was the nation's largest military base in the west.[40] Grant was happy with his new commander, but looked forward to the end of his military service and a possible teaching career.[41]

Marriage and family

In Missouri, Grant visited Dent's family and became engaged to his sister, Julia, in 1844.[41] Four years later on August 22, 1848, they were married at Julia's home in St. Louis. Grant's abolitionist father Jesse, who disapproved of the Dents owning slaves, refused to attend their wedding, which took place without either of Grant's parents.[42] Grant was flanked by three fellow West Point graduates, all dressed in their blue uniforms, including Longstreet, Julia's cousin.[43][lower-alpha 6] At the end of the month, Julia was nevertheless warmly received by Grant's family in Bethel, Ohio.[46] They had four children: Frederick, Ulysses Jr. ("Buck"), Ellen ("Nellie"), and Jesse.[47] After the wedding, Grant obtained a two-month extension to his leave and returned to St. Louis when he decided, with a wife to support, that he would remain in the army.[48]

Mexican–American War

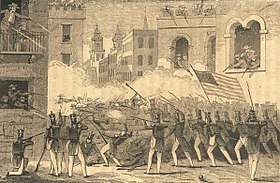

After rising tensions with Mexico following the United States' annexation of Texas, war broke out in 1846. During the conflict, Grant distinguished himself as a daring and competent soldier.[49] Before the war President John Tyler had ordered Grant's unit to Louisiana as part of the Army of Observation under Major General Zachary Taylor.[50] In September 1846, Tyler's successor, James K. Polk, unable to provoke Mexico into war at Corpus Christi, Texas, ordered Taylor to march 150 miles south to the Rio Grande. Marching south to Fort Texas, to prevent a Mexican siege, Grant experienced combat for the first time on May 8, 1846, at the Battle of Palo Alto.[51]

Grant was tapped to serve as regimental quartermaster,[52] but yearned for a combat role; when finally allowed, he led a cavalry charge at the Battle of Resaca de la Palma. He demonstrated his equestrian ability at the Battle of Monterrey by carrying a dispatch past snipers while hanging off the side of his horse, keeping the animal between him and the enemy.[53] Before leaving the city he stopped at a house occupied by wounded Americans, giving them assurance he would send for help.[54] Polk, wary of Taylor's growing popularity, divided his forces, sending some troops (including Grant's unit) to form a new army under Major General Winfield Scott.[55] Traveling by sea, Scott's army landed at Veracruz and advanced toward Mexico City.[56] The army met the Mexican forces at the battles of Molino del Rey and Chapultepec outside Mexico City.[57] For his bravery at Molino del Rey, Grant was brevetted first lieutenant on September 30.[58] At San Cosmé, men under Grant's direction dragged a disassembled howitzer into a church steeple, reassembled it, and bombarded nearby Mexican troops.[57] His bravery and initiative earned him his second brevet promotion to captain.[59] On September 14, 1847, Scott's army marched into the city; Mexico ceded the vast territory, including California, to the U.S. on February 2, 1848.[60]

During the war, Grant established a commendable record, studied the tactics and strategies of Scott and Taylor, and emerged as a seasoned officer, writing in his memoirs that this is how he learned much about military leadership.[61] In retrospect, although he respected Scott[62] he identified his leadership style with Taylor's. However, Grant also wrote that the Mexican War was wrong and the territorial gains were designed to expand slavery, stating, "I was bitterly opposed to the measure ... and to this day, regard the war, which resulted, as one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation." He opined that the Civil War was divine punishment on the nation for its aggression in Mexico.[63] During the war, Grant discovered his "moral courage" and began to consider a career in the army.[64]

Post-war assignments

Grant's first post-war assignments took him and Julia to Detroit on November 17, 1848, only to find that after his four-month leave of absence he was replaced as quartermaster and was sent to Madison Barracks, a desolate outpost at Sackets Harbor in upstate New York, in bad need of supplies and repair.[65] Concerned for Julia, Grant filed an official complaint requesting a transfer. When Ulysses had spare cash he would travel to nearby Watertown and buy supplies for himself and gifts for Julia in a dry goods store.[lower-alpha 7] After a four-month stay, Grant's request for transfer was approved and he was sent back to Detroit where he resumed his job as regimental quartermaster.[66]

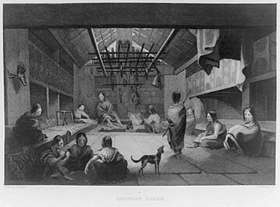

When the discovery of gold in California brought droves of prospectors and settlers to the territory, Grant and the 4th infantry were ordered to reinforce the small garrison there. Grant was charged with bringing the soldiers and a few hundred civilians from New York City to Panama, overland to the Pacific and then north to California. Julia, eight months pregnant with Ulysses Jr., did not accompany him. While in Panama a cholera epidemic broke out and claimed many lives of soldiers, civilians and children. In Panama City, Grant established and organized a field hospital and moved the worst cases to a hospital barge one mile offshore.[67] When orderlies protested to tending the sick, Grant did much of the nursing himself, earning high praise from observers.[68] In August, Grant arrived in San Francisco, a busy Gold Rush boomtown. Grant's next assignment sent him north to Vancouver Barracks in the then Oregon Territory.[69][lower-alpha 8]

To supplement a military salary which was inadequate to support his family, Grant speculated and failed at several business ventures, confirming his father's belief that he had no head for business.[71] Grant assured Julia in a letter that local Native Americans were harmless, while he developed an empathy for the plight of Indians from the "unjust treatment" by white men.[72] Promoted to captain on August 5, 1853, Grant was assigned to command Company F, 4th Infantry, at the newly constructed Fort Humboldt in California.[73] He arrived at the fort on January 5, 1854, and reported to its commander Lieutenant Colonel Robert C. Buchanan.[74] Grant was bored and depressed about being separated from his wife, and he began to drink.[75] An officer who roomed with Grant reported the affair to Colonel Buchanan, who reprimanded Grant for one drinking episode. Grant told Buchanan if he did not reform he would resign. One Sunday, Grant was again rumored to have been found at his company's paytable influenced by drink. Keeping his pledge to Buchanan, Grant resigned, effective July 31, 1854, without explanation.[76] Buchanan endorsed Grant's letter of resignation but did not submit any report that verified the incident.[77][lower-alpha 9] Grant was neither arrested nor faced court-martial, while the War Department stated, "Nothing stands against his good name."[82] Grant said years later, "the vice of intemperance (drunkenness) had not a little to do with my decision to resign."[83] With no means of support, Grant returned to St. Louis and reunited with his family, uncertain about his future.[84]

Civilian struggles and politics

At age 32, with no civilian vocation, Grant needed work to support his growing family. It was the beginning of seven financially lean years. His father offered him a place in the Galena, Illinois, branch of the family's leather business on condition that Julia and the children stay with her parents in Missouri or with the Grants in Kentucky. Ulysses and Julia opposed another separation and declined the offer. In 1855, Grant farmed on his brother-in-law's property near St. Louis, using slaves owned by Julia's father.[85] The farm was not successful and to earn money he sold firewood on St. Louis street corners.[86] Earning only $50 a month (equivalent to $1,310 in 2017), wearing his faded army jacket, an unkempt Grant desperately looked for work.[87] The next year, the Grants moved to land on Julia's father's farm, and built a home Grant called "Hardscrabble". Julia disliked the rustic house, which she described as an "unattractive cabin".[88] The Panic of 1857 devastated farmers, including Grant, who pawned his gold watch to pay for Christmas.[89] In 1858, Grant rented out Hardscrabble and moved his family to Julia's father's 850-acre plantation that used slave labor.[90] That fall, after a bout of malaria, Grant retired from farming.[91]

The same year, Grant acquired a slave from his father-in-law, a thirty-five-year-old man named William Jones.[92] In March 1859, Grant freed William, worth about $1,500, instead of selling him at a time when he needed money.[93] Grant moved to St. Louis, taking on a partnership with Julia's cousin Harry Boggs working in the real estate business as a bill collector, again without success, and at Julia's recommendation he dissolved his partnership.[94] In August, Grant applied for a position as county engineer, believing his education qualified him for the job. His application came with thirty-five notable recommendations, but Grant correctly assumed the position would be given on the basis of political affiliation and was passed over by the Free Soil and Republican county commissioners because he was believed to share his father-in-law's Democratic sentiments.[95] In the 1856 presidential election, Grant cast his first presidential vote for Democrat James Buchanan, later saying he was really voting against Republican John C. Frémont over concern that his anti-slavery position would lead to southern secession and war and because he considered Frémont to be a shameless self-promoter.[96] Although Grant was not an abolitionist, he was not considered a "slavery man", and could not bring himself to force slaves to do work.[97]

In April 1860, Grant and his family moved north to Galena, accepting a position in his father's leather goods business run by his younger brothers Simpson and Orvil.[98][lower-alpha 10] In a few months, Ulysses paid off the debts he acquired in Missouri.[100] Ulysses and family attended the local Methodist church and he soon established himself as a reputable citizen of Galena.[101] For the 1860 election, he could not vote because he was not yet a legal resident of Illinois, but he favored Democrat Stephen A. Douglas over the eventual winner, Abraham Lincoln, and Lincoln over the Southern Democrat, John C. Breckinridge.[102] He was torn between his increasingly anti-slavery views and the fact that his wife remained a staunch Democrat.[103]

Civil War

On April 12, 1861, the American Civil War began when Confederate troops attacked Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina.[104] The news came as a shock in Galena, and Grant shared his neighbors' concern about the war.[105] On April 15, Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers.[106] On April 16, Grant attended a mass meeting held in Galena to assess the crisis and encourage recruitment, and a speech by his father's attorney, John Aaron Rawlins, stirred Grant's patriotism.[107][lower-alpha 11] Ready to fight, Grant recalled with satisfaction, "I never went into our leather store again."[108][lower-alpha 12] On April 18, Grant chaired a second recruitment meeting,[110] but turned down a captain's position as commander of the newly-formed militia company, hoping his previous experience would aid him to obtain more senior military rank.[111]

Early commands

Grant's early efforts to be recommissioned failed, rejected by Major General George B. McClellan and Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon. On April 29, supported by Congressman Elihu B. Washburne of Illinois, Grant was appointed military aide to Governor Richard Yates, and mustered ten regiments into the Illinois militia. On June 14, again aided by Washburne, Grant was promoted to Colonel and put in charge of the unruly 21st Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment, which he soon restored to good order and discipline.[112] Colonel Grant and his 21st Regiment were transferred to Missouri to dislodge reported Confederate forces.[113]

On August 5, with Washburne's aid, Grant was appointed Brigadier General of volunteers.[114] Major General John C. Frémont, Union commander of the West, passed over senior generals and appointed Grant commander of the District of Southeastern Missouri.[115][lower-alpha 13] Grant set up his headquarters at Cairo, Illinois, a bustling Union military and naval base, that was to be used to launch a joint campaign down the Mississippi, Tennessee, and Cumberland rivers.[117] After the Confederates moved into western Kentucky, with designs on southern Illinois, Grant, who notified Frémont, advanced on Paducah, Kentucky, taking it without a fight on September 6, and set up a supply station.[118] Having understood the importance to Lincoln about Kentucky's neutrality, Grant assured its citizens, "I have come among you not as your enemy, but as your friend."[119] On November 1, Frémont ordered Grant to "make demonstrations" against the Confederates on both sides of the Mississippi, but prohibited him from attacking the enemy.[120]

Belmont, Forts Henry and Donelson

On November 2, 1861, Lincoln sacked Frémont from command, a move that freed up Grant to make a planned attack from Cairo on Confederate soldiers encamped in Belmont, Missouri.[120][lower-alpha 14] On November 7, Grant, along with Brigadier General John A. McClernand, landed 2,500 men at Hunter's Point, two miles north of the Confederate base outside Belmont.[122] The Union army took the camp, but the reinforced Confederates under Brigadier Generals Frank Cheatham and Gideon J. Pillow forced a chaotic Union retreat.[123] Grant had wanted to destroy Confederate strongholds at both Belmont, Missouri and Columbus, Kentucky, but was not given enough troops and was only able to disrupt their positions. Grant's troops had to fight their way back to their Union boats and escaped back to Cairo under fire from the heavily fortified stronghold at Columbus.[124] A tactical defeat, the battle gave Grant's volunteers confidence and experience.[125] Also, President Lincoln noticed that Grant was a general willing to fight.[126]

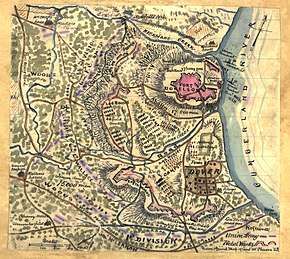

Confederate-held Columbus blocked Union access to the lower Mississippi. Grant, and General James B. McPherson, came up with a plan to bypass Columbus and with a force of 25,000 troops, move against Fort Henry on the Tennessee River and then ten miles east to Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River, with the aid of gunboats, opening both rivers and allowing the Union access further south. Grant presented his plan to Henry Halleck, his new commander under the newly created Department of Missouri.[127] Halleck was considering the same strategy, but rebuffed Grant, believing he needed twice the number of troops. However, after Halleck telegraphed and consulted McClellan about the plan, he finally agreed on condition that the attack be conducted in close cooperation with navy Flag Officer, Andrew H. Foote.[128] Foote's gunboats bombarded Fort Henry, leading to its surrender on February 6, 1862, before Grant's infantry even arrived.[129]

Grant then ordered an immediate assault on Fort Donelson, under the command of John B. Floyd, which dominated the Cumberland River. Unlike Fort Henry, Grant was now going up against a force equal to his. Unaware of the garrison's strength, Grant's forces were over-confident. Grant, McClernand, and Smith positioned their divisions around the fort. The next day McClernand and Smith launched probing attacks on apparent weak spots in the Confederate line, only to retreat with heavy losses. On February 14, Foote's gunboats began bombarding the fort, only to be repulsed by its heavy guns. Foote himself was wounded. Thus far the Confederates were winning, but soon Union reinforcements arrived, giving Grant a total force of over 40,000 men. When Foote regained control of the river, Grant resumed his attack resulting in a standoff. That evening, Floyd called a council of war, unsure of his next action. Grant received a dispatch from Foote, requesting that they meet. Grant mounted a horse and rode seven miles over freezing roads and trenches, reaching Smith's division, instructing him to prepare for the next assault, and rode on and met up with McClernand and Wallace. After exchanging reports, he met up with Foote. On February 16, Foote resumed his bombardment, which signaled a general attack. Floyd and Pillow fled, leaving the fort in command of Simon Bolivar Buckner, who submitted to Grant's demand for "unconditional and immediate surrender".[130]

Grant had won the first major victory for the Union, capturing Floyd's entire rebel army of more than 12,000. Halleck was angry that Grant had acted without his authorization and complained to McClellan, accusing Grant of "neglect and inefficiency". On March 3, Halleck sent a telegram to Washington complaining that he had no communication with Grant for a week. Three days later, Halleck followed up with a postscript claiming "word has just reached me that ... Grant has resumed his bad habits (of drinking)."[131] Lincoln, regardless, promoted Grant to major general of volunteers while the Northern press treated Grant as a hero. Playing off his initials, they took to calling him "Unconditional Surrender Grant."[132]

Shiloh and aftermath

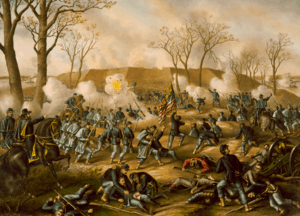

As the great numbers of troops from both armies gathered, it was widely thought in the North that another western battle might end the war.[133] Grant, reinstated by Halleck at Lincoln's and Stanton's urging, left Fort Henry and traveled by boat up the Tennessee River to rejoin his army with orders to advance with the Army of the Tennessee into Tennessee. Grant's main Union army was located at Pittsburg Landing, while 40,000 Confederate troops converged at Corinth.[134] Brigadier General William Tecumseh Sherman assured Grant that his green troops were ready for an attack. Grant agreed and wired Halleck with their assessment.[135] Grant, whose forces numbered 45,000, wanted to attack the Confederates at Corinth, but Halleck ordered him not to attack until Major General Don Carlos Buell arrived with his division of 25,000.[136] Meanwhile, Grant prepared for an attack on the Confederate army of roughly equal strength. Instead of preparing defensive fortifications between the Tennessee River and Owl Creek,[lower-alpha 15] and clearing fields of fire, they spent most of their time drilling the largely inexperienced troops while Sherman dismissed reports of nearby Confederates.[137]

Union inaction created the opportunity for the Confederates to attack first before Buell arrived.[138] On the morning of April 6, 1862, Grant's troops were taken by surprise when the Confederates, led by Generals Albert Sidney Johnston and P.G.T. Beauregard, struck first "like an Alpine avalanche" near Shiloh church, attacking five divisions of Grant's army and forcing a confused retreat toward the Tennessee River.[139] Johnston was wounded and died and command fell upon Beauregard.[140] One Union line held the Confederate attack off for several hours at a place later called the "Hornet's Nest", giving Grant time to assemble artillery and 20,000 troops near Pittsburg Landing.[141] The Confederates finally broke through the Hornet's Nest to capture a Union division, but "Grant's Last Line" held Pittsburg Landing, while the exhausted Confederates, lacking reinforcements, halted their advance.[142] The day's fighting had been costly, with thousands of troops killed and wounded. That evening, heavy rain set in. Sherman found Grant standing alone under a tree in the rain. "Well, Grant, we've had the devil's own day of it, haven't we?" Sherman said. "Yes," replied Grant. "Lick 'em tomorrow, though."[143]

Bolstered by 18,000 fresh troops from the divisions of Major Generals Buell and Lew Wallace, Grant counterattacked at dawn the next day and regained the field, forcing the disorganized and demoralized rebels to retreat back to Corinth while thousands deserted.[144] Halleck ordered Grant not to advance more than one day from Pittsburg Landing, stopping the pursuit of the Confederate Army.[145] Although Grant had won the battle the situation was little changed, with the Union in possession of Pittsburg Landing and the Confederates once again holed up in Corinth.[146] Grant, now realizing that the South was determined to fight and that the war would not be won with one battle, would later write, "Then, indeed, I gave up all idea of saving the Union except by complete conquest."[147]

Shiloh was the costliest battle in American history to that point and the staggering 23,746 total casualties stunned the nation.[148] Briefly hailed a hero for routing the Confederates, Grant was soon mired in controversy.[149] The Northern press castigated Grant for shockingly high casualties, and accused him of drunkenness during the battle, contrary to the accounts of officers and others with him at the time.[150][lower-alpha 16] However, Grant's victory at Shiloh ended any chance for the Confederates to prevail in the Mississippi valley or regain its strategic advantage in the West.[151]

Halleck arrived from St. Louis on April 11, took command, and assembled a combined army of about 120,000 men. On April 29, he relieved Grant of field command and replaced him with Major General George Henry Thomas. Halleck slowly marched his army to take Corinth, entrenching each night.[152] Meanwhile, Beauregard pretended to be reinforcing, sent "deserters" to the Union Army with that story, and moved his army out during the night, to Halleck's surprise when he finally arrived at Corinth on May 30.[153] Discouraged, Grant considered resigning but Sherman convinced him to stay.[154] Lincoln dismissed Grant's critics, saying "I can't spare this man; he fights."[155] Halleck divided his combined army and reinstated Grant as field commander of the Army of the Tennessee on July 11.[156]

On September 19, Grant's army defeated Confederates at the Battle of Iuka, then successfully defended Corinth, inflicting heavy casualties.[157] On October 25, Grant assumed command of the District of the Tennessee.[158] In November, after Lincoln's preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, Grant ordered units under his command to incorporate former slaves into the Union Army, giving them clothes, shelter and wages for their services.[159]

Vicksburg campaign

The Confederate stronghold of Vicksburg, Mississippi, blocked the way of Union control of the Mississippi River, making its capture vital.[160] Grant's Army held western Tennessee with almost 40,000 troops available to fight.[161] Grant was aggravated to learn that Lincoln authorized McClernand to raise a separate army for the purpose.[162] Halleck ordered McClernand to Memphis, and placed him and his troops under Grant's authority.[163] After Grant's army captured Holly Springs, Grant planned to attack Vicksburg's front overland while Sherman would attack the fortress from the rear on the Mississippi River.[164] However, Confederate cavalry raids on December 11 and 20 broke Union communications and recaptured Holly Springs, preventing the armies of Grant and Sherman from connecting.[165] On December 29, a Confederate army led by Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton repulsed Sherman's direct approach ascending the bluffs to Vicksburg at Chickasaw Bayou.[166] McClernand reached Sherman's army, assumed command, and independently of Grant led a campaign that captured Confederate Fort Hindman.[167] During this time, Grant incorporated fleeing African American slaves into the Union Army giving them protection and paid employment.[168]

Along with his military responsibilities in the months following Grant's return to command, he was concerned over an expanding illicit cotton trade in his district.[169] He believed the trade undermined the Union war effort, funded the Confederacy, and prolonged the war, while Union soldiers died in the fields.[170] Grant's own father, together with some Jewish partners, the Mack Brothers, attempted to gain access to this lucrative trade through Ulysses Grant. On December 17, he issued General Order No. 11, expelling "Jews, as a class," from the district, saying that Jewish merchants were violating trade regulations.[171] Historian Jonathan D. Sarna called it "the most notorious anti-Jewish official order in American history."[172] Historians' opinions vary on Grant's motives for issuing the order and whether his father's involvement provoked an intemperate response.[173] [143]Jewish leaders complained to Lincoln while the Northern press criticized Grant.[174] Lincoln demanded the order be revoked and Grant rescinded it within three weeks.[175] When asked about the general order after the war, Grant explained: "During war times these nice distinctions were disregarded, we had no time to handle things with kid gloves."[176][lower-alpha 17]

.tif.jpg)

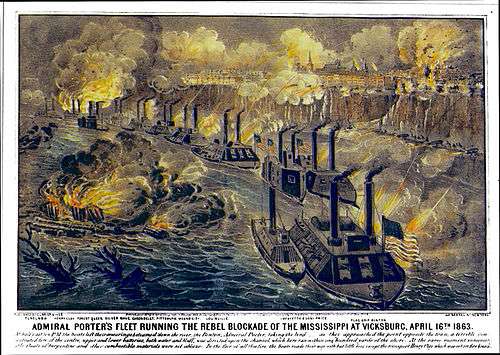

On January 29, 1863, Grant assumed overall command and attempted to advance his army through water-logged terrain to bypass Vicksburg's guns, while the green Union soldiers gained valuable experience.[178] On April 16, Grant ordered Admiral David Dixon Porter's gunboats south under fire from the Vicksburg batteries to meet up with his troops who had marched south down the west side of the Mississippi River.[179] Grant ordered diversionary battles, confusing Pemberton and allowing Grant's army to move east across the Mississippi, landing troops at Bruinsburg.[180] Grant's army captured Jackson, the state capital. Advancing his army to Vicksburg, Grant defeated Pemberton's army at the Battle of Champion Hill on May 16, forcing their retreat into Vicksburg.[181] After Grant's men assaulted the entrenchments twice, suffering severe losses, they settled in for a siege lasting seven weeks. During quiet periods of the campaign Grant would take to drinking on occasion.[182] The personal rivalry between McClernand and Grant continued until Grant removed McClernand from command when he contravened Grant by publishing an order without permission.[183] Pemberton surrendered Vicksburg to Grant on July 4, 1863.[184]

Vicksburg's fall gave Union forces control of the Mississippi River and split the Confederacy. By that time, Grant's political sympathies fully coincided with the Radical Republicans' aggressive prosecution of the war and emancipation of the slaves.[185] The success at Vicksburg was a morale boost for the Union war effort.[183] When Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton suggested Grant be brought back east to run the Army of the Potomac, Grant demurred, writing that he knew the geography and resources of the West better and he did not want to upset the chain of command in the East.[186]

Chattanooga and promotion

Lincoln promoted Grant to major general in the regular army and assigned him command of the newly formed Division of the Mississippi on October 16, 1863, including the Armies of the Ohio, Tennessee, and Cumberland.[187] After the Battle of Chickamauga, the Army of the Cumberland retreated into Chattanooga where they became trapped.[188] Taking command, Grant arrived in Chattanooga by horseback with plans to resupply the city and break the siege.[189] Lincoln also sent Major General Joseph Hooker to assist Grant. Union forces captured Brown's Ferry and opened a supply line to Bridgeport.[190] On November 23, Grant organized three armies to attack at Missionary Ridge and Lookout Mountain. Two days later, Hooker's forces took Lookout Mountain.[191] Grant ordered Major General George Henry Thomas to advance when Sherman's army failed to take Missionary Ridge from the northeast.[192] The Army of the Cumberland, led by Major General Philip Sheridan and Brigadier General Thomas J. Wood, charged uphill and captured the Confederate entrenchments at the top, forcing a retreat.[193] The decisive battle gave the Union control of Tennessee and opened Georgia, the Confederate heartland, to Union invasion.[194] Grant was given an enormous thoroughbred horse, Cincinnati, by a thankful admirer in St. Louis.[195][lower-alpha 18]

On March 2, 1864, Lincoln promoted Grant to lieutenant general, giving him command of all Union Armies, answering only to the president.[197] Grant arrived in Washington on March 8, and he was formally commissioned by Lincoln the next day at a Cabinet meeting.[198] Grant developed a good working relationship with Lincoln, who allowed Grant to devise his own strategy as long as Lee was defeated.[199] Grant established his headquarters with General George Meade's Army of the Potomac in Culpeper, north-west of Richmond, and met weekly with Lincoln and Stanton in Washington.[200][lower-alpha 19] After protest from Halleck, Grant scrapped a risky invasion plan of North Carolina, and adopted a plan of five coordinated Union offensives on five fronts, so Confederate armies could not shift troops along interior lines.[202] Grant and Meade would make a direct frontal attack on Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, while Sherman, whom Grant named chief of the western armies, was to destroy Joseph E. Johnston's Army of Tennessee and take Atlanta.[203] Major General Benjamin Butler would advance on Lee from the southeast, up the James River, while Major General Nathaniel Banks would capture Mobile.[204] Major General Franz Sigel was to capture granaries and rail lines in the Shenandoah Valley that supplied the Confederate Army.[205] Grant commanded in total 533,000 battle-ready troops spread out over an eighteen-mile front, while the Confederates had lost many officers in battle and had great difficulty finding replacements.[206]

Grant's own popularity had risen, and there was talk that a Union victory early in the year could lead to his candidacy for the presidency. He was aware of the rumors, but had ruled out a political candidacy; the possibility would soon vanish with delays on the battlefield.[207]

Overland Campaign and Petersburg Siege

The Overland Campaign was a series of brutal battles fought in Virginia for seven weeks during May and June 1864.[208] Sigel's and Butler's efforts failed, and Grant was left alone to fight Lee.[209] On the morning of Wednesday, May 4, dressed in his full uniform, with sword at his side, Grant rode out from his headquarters at Culpeper towards Germanna Ford, mounted on his war horse, Cincinnati.[210] That day Grant crossed the Rapidian unopposed, while supplies were transported on four pontoon bridges.[211] On May 5, the Union army attacked Lee in the Wilderness, a three-day battle with estimated casualties of 17,666 Union and 11,125 Confederate.[212] Rather than retreat, Grant flanked Lee's army to the southeast and attempted to wedge his forces between Lee and Richmond at Spotsylvania Court House.[213] Lee's army got to Spotsylvania first and a costly battle ensued, lasting thirteen days, with high casualties.[214] On May 12, Grant attempted to break through Lee's Muleshoe salient guarded by Confederate artillery, resulting in one of the bloodiest assaults of the Civil War, known as the Bloody Angle.[215] Unable to break Lee's lines, Grant again flanked the rebels to the southeast, meeting at North Anna, where a battle lasted three days.[216]

Grant maneuvered his army to Cold Harbor, a vital railroad hub that linked to Richmond, but Lee's men had the defensive advantage and were already entrenched. On the third day of the thirteen-day battle, Grant led a costly assault and was soon castigated as "the Butcher" by the Northern press after taking 52,788 Union casualties; Lee's Confederate army suffered 32,907 casualties, but he was less able to replace them.[217] This battle was the second of two that Grant later said he regretted (the other being his initial assault on Vicksburg). Undetected by Lee, Grant moved his army south of the James River, freed Butler from the Bermuda Hundred, and advanced toward Petersburg, Virginia's central railroad hub.[218] After crossing the James, Grant arrived at Petersburg, threatening nearby Richmond. Beauregard defended the city, and Lee's veteran reinforcements soon arrived, resulting in a nine-month siege. Northern resentment grew as the war dragged on. Lee was forced to defend Richmond, unable to reinforce other Confederate forces. Sheridan was assigned command of the Union Army of the Shenandoah and Grant directed him to "follow the enemy to their death" and to destroy vital Confederate supplies in the Shenandoah Valley. When Sheridan reported suffering attacks by John S. Mosby's irregular Confederate cavalry, Grant recommended rounding up their families for imprisonment as hostages at Fort McHenry.[219] After Grant's abortive attempt to capture Petersburg, Lincoln supported Grant in his decision to continue. Because of the high casualties, Lincoln arrived at Grant's headquarters at City Point on June 21 to assess the state of Grant's army, meeting with Grant and Admiral Porter. By the time Lincoln departed his appreciation for Grant had grown.[220]

At Petersburg, Grant approved a plan to blow up part of the enemy trenches from an underground tunnel. The explosion created a crater, into which poorly led Union troops poured. Recovering from the surprise, Confederates surrounded the crater and easily picked off Union troops within it. The Union's 3,500 casualties outnumbered the Confederates' by three-to-one; although the plan could have been successful if implemented correctly, Grant admitted the tactic had been a "stupendous failure".[221] Rather than fight Lee in a full frontal attack as he had done at Cold Harbor, Grant continued to extend Lee's defenses south and west of Petersburg to capture essential railroad links.[222]

After the Federal army rebuilt the City Point Railroad, Grant used mortars to attack Lee's overstretched forces.[223] Union forces soon captured Mobile Bay and Atlanta and now controlled the Shenandoah Valley, ensuring Lincoln's reelection in November.[224] Sherman convinced Grant and Lincoln to send his army to march on Savannah and devastate the Confederate heartland.[225] Sherman cut a 60-mile path of destruction of Southern infrastructure unopposed, reached the Atlantic Ocean, and captured Savannah on December 22.[226] On December 16, after much prodding by Grant, the Union Army under Thomas smashed Hood's Confederate Army at Nashville.[227] It was the beginning of the end for the Confederacy, with Lee's forces at Petersburg being the only significant obstacle remaining.[228]

By March 1865, Grant had severely weakened Lee's strength, having extended his lines to 35 miles.[229] Lee's troops deserted by the thousands due to hunger and the strains of trench warfare.[230] Grant, Sherman, Porter, and Lincoln held a conference to discuss the surrender of Confederate armies and Reconstruction of the South on March 28.[231]

Appomattox campaign, and victory

On April 2, Grant ordered a general assault on Lee's entrenched forces. Union troops took Petersburg and captured an evacuated Richmond the following day.[232] Lee and part of his army broke free and attempted to link up with the remnants of Joseph E. Johnston's defeated army, but Sheridan's cavalry stopped the two armies from converging, cutting them off from their supply trains.[233] Grant was in communication with Lee before he entrusted his aide Orville Babcock to carry his last dispatch to Lee requesting his surrender with instructions to escort him to a meeting place of Lee's choosing.[234] Grant immediately mounted his horse, Cincinnati, and rode west, bypassing Lee's army, to join Sheridan who had captured Appomattox Station, blocking Lee's escape route. On his way Grant was hailed by a member of Meade's staff carrying a letter sent by Lee through the picket lines, informing Grant that he was ready to formally surrender.[235]

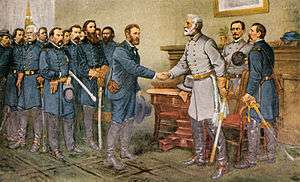

On April 9, Grant and Lee met at Appomattox Court House.[236] Upon receiving Lee's dispatch about the proposed meeting Grant had been jubilant. Although Grant felt depressed at the fall of "a foe who had fought so long and valiantly," he believed the Southern cause was "one of the worst for which a people ever fought."[237] After briefly discussing their days of old in Mexico, Grant wrote out the terms of surrender, whereupon Lee expressed satisfaction and accepted Grant's terms.[238] Going beyond his military authority, Grant gave Lee and his men amnesty; Confederates would surrender their weapons and return to their homes. At Lee's request, Grant also allowed them to keep their horses, all on the condition that they would not take up arms against the United States.[239] Grant ordered his troops to stop all celebration, saying the "war is over; the rebels are our countrymen again."[240] Confederate forces surrendered to Union armies, Johnson's Tennessee army on April 26, Richard Taylor's Alabama army on May 4, and Kirby Smith's Texas army on May 26, the war ended.[241]

Lincoln's assassination

On April 14, 1865, five days after Grant's victory at Appomattox, he attended a cabinet meeting in Washington. Lincoln invited him and his wife to Ford's Theater, but they declined as upon his wife Julia's urging, had plans to travel to Philadelphia. In a conspiracy that also targeted top cabinet members, and in a last effort to topple the Union, Lincoln was fatally shot by John Wilkes Booth at the theater, and died the next morning.[242] Many, including Grant himself, thought that he had been a target in the plot.[243] Stanton notified him of the President's death and summoned him back to Washington. Vice President Andrew Johnson was sworn in as President on April 15. Attending Lincoln's funeral on April 19, Grant stood alone and wept openly; he later said Lincoln was "the greatest man I have ever known."[244] Upon Johnson's assuming the presidency, Grant told Julia that he dreaded the change in administrations; he judged Johnson's attitude toward white southerners as one that would "make them unwilling citizens", and feared that the Civil War would be revived.[245]

Commanding General

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

At the war's end, Grant remained commander of the army, with duties that included dealing with Maximilian and French troops in Mexico, enforcement of Reconstruction in the former Confederate states, and supervision of Indian wars on the western Plains.[246] Grant secured a house for his family in Georgetown Heights in 1865, but instructed Elihu Washburne that for political purposes his legal residence remained in Galena, Illinois.[247] That same year, Grant spoke at Cooper Union in New York in support of Johnson's presidency. Further travels that summer took the Grants to Albany, New York, back to Galena, and throughout Illinois and Ohio, with enthusiastic receptions.[248] On July 25, 1866, Congress promoted Grant to the newly created rank of General of the Army of the United States.[249]

Reconstruction

Reconstruction was a turbulent period from 1863–1877 when former Confederate states were readmitted to the Union, "during which the nation's laws and Constitution were rewritten to guarantee the basic rights of the former slaves, and biracial governments came to power throughout the defeated Confederacy."[250] In November 1865, Johnson sent Grant on a fact-finding mission to the South. Grant recommended continuation of a reformed Freedmen's Bureau, which Johnson opposed, but advised against using black troops, which he believed encouraged an alternative to farm labor.[251] Grant did not believe the people of the South were ready for self-rule, and that both whites and blacks in the South required protection by the federal government. Concerned that the war led to a diminished respect for civil authorities, Grant continued using the Army to maintain order.[252] On the same day the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified, Grant filed an unconvincing and optimistic report of his tour, expressing his faith that "the mass of thinking men of the South accept the present situation of affairs in good faith."[253] In this respect Grant's opinion on Reconstruction aligned with Johnson's policy of restoring former Confederates to their positions of power, arguing that Congress should allow representatives from the South to take their seats.[254] Grant, like Lincoln, out of a sense of duty, believed the federal government was responsible to all Union Army veterans who served in the war, both white and black.[255]

Relationship with Johnson

Grant was initially optimistic about Johnson, saying he was satisfied the nation had "nothing to fear" from the Johnson administration.[256] Despite differing styles, Grant got along cordially with Johnson, and he was allowed to attend cabinet meetings concerning Reconstruction.[256] Grant's report on his tour of the South was aligned with Johnson's conservative policies (Grant later disavowed the report).[253] By February 1866, the relationship between Grant and Johnson began to break apart.[257] Johnson opposed Grant's closure of the Richmond Examiner for disloyal editorials.[257] Grant's team of commanders enforced the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1866, passed over Johnson's veto.[257] Needing Grant's popularity, Johnson took Grant on his "Swing Around the Circle" tour, a failed attempt to gain national support for lenient policies toward the South.[258] Grant privately called Johnson's speeches a "national disgrace" and he left the tour early.[259] On March 2, 1867, overriding Johnson's veto, Congress passed the first of three Reconstruction Acts, which divided the southern states into five military districts, putting in charge military officers to enforce Reconstruction policy.[260] Protecting Grant, Congress passed the Command of the Army Act, attached to an army appropriation bill, preventing his removal or relocation, and forcing Johnson to pass orders through Grant.[261]

In August 1867, Johnson suspended Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, a Lincoln appointee who sympathized with Congressional Reconstruction, replacing him with Grant as acting Secretary.[262][lower-alpha 20] Stanton was a Radical Republican protected by allies in Congress.[264] Grant wanted to replace him but recommended against bypassing the Tenure of Office Act, prohibiting a cabinet removal without Senate approval.[265] Grant accepted the position, not wanting the Army to fall under a conservative appointee who would impede Reconstruction, and managed an uneasy partnership with Johnson.[266] In December 1867 Congress voted to keep Stanton who was reinstated by a Senate Committee on January 10, 1868. Grant told Johnson he was going to resign office to avoid fines and imprisonment. Johnson, who was scheming to get rid of Grant, told him he would assume all such responsibility and asked him to delay his resignation until a suitable replacement could be found, believing Grant had agreed to do so.[263] When the Senate voted and reinstated Stanton, Grant surrendered the office before Johnson had an opportunity to appoint a replacement.[267] Johnson was livid at Grant, accusing him of lying at a stormy cabinet meeting. The publication of angry messages between Grant and Johnson led to a complete break between the president and his general.[268] The controversy led to Johnson's impeachment and trial in the Senate.[264] Johnson was saved from removal from office by one vote.[269] The break with Johnson popularized Grant among Republicans and made him the uncontested candidate for the presidency in 1868.[270]

Election of 1868

When the Republican Party met at the 1868 Republican National Convention in Chicago, the delegates unanimously nominated Grant for president and Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax, for vice president.[264] Although Grant had preferred to remain in the army, he accepted the Republican nomination, believing that he was the only one who could unify the nation.[271] The Republicans advocated "equal civil and political rights to all" and African American enfranchisement.[272][273] The Democrats, having abandoned Johnson, nominated former governor Horatio Seymour (New York) for president and Francis P. Blair (Missouri) for vice president.[274] The Democrats advocated the immediate restoration of former Confederate states to the Union and amnesty from "all past political offenses".[275]

Grant played no overt role during the campaign and instead was joined by Sherman and Sheridan in a tour of the West that summer.[276] However, the Republicans adopted his words "Let us have peace" as their campaign slogan.[277] Grant's 1862 General Order No. 11 became an issue during the presidential campaign; he sought to distance himself from the order, saying "I have no prejudice against sect or race, but want each individual to be judged by his own merit."[278] The Democrats and their Klan supporters focused mainly on ending Reconstruction and returning control of the South to the white Democrats and the planter class, which alienated many War Democrats in the North.[279] To intimidate blacks from voting Republican, the Klan, led by former Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest, used violence and intimidation across the South in three states: Kansas, Georgia, and Louisiana.[280] Grant won the popular vote by 300,000 votes out of 5,716,082 votes cast, receiving an Electoral College landslide of 214 votes to Seymour's 80.[281] Seymour received a majority of white votes, but Grant was aided by 500,000 votes cast by blacks,[274] winning him 54.7 percent of the popular vote.[282] At the age of 46, Grant was the youngest president yet elected, and the first president after the nation had outlawed slavery.[283]

Presidency (1869–1877)

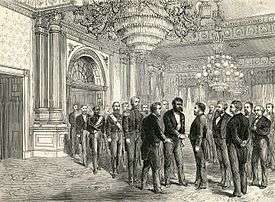

On March 4, 1869, Grant was sworn in as the eighteenth President of the United States by Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase. Grant assumed the presidency with reluctance, which he expressed in an 1868 letter, after his nomination, to his close friend Sherman:

I have been forced into it in spite of myself. I could not back down without, as it seems to me, leaving the contest for power for the next four years between mere trading politicians, the elevation of whom, no matter which party won, would lose to us, largely, the results of the costly war which we have gone through.[284]

Grant's presidency began unusually, as President Johnson, at the time angry with Grant, did not attend Grant's inauguration or ride with him as he departed the White House for the last time.[285] In his inaugural address, Grant urged the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment, while large numbers of African Americans attended his inauguration.[286] He also urged that bonds issued during the Civil War should be paid in gold and called for reform in Indian Policy while he recommended the "proper treatment" of Native Americans and encouraged their "civilization and ultimate citizenship".[287]

Grant's cabinet appointments were made without senatorial approval and sparked both criticism and approval.[288] Grant chose two close friends for important posts: Elihu B. Washburne for Secretary of State and John A. Rawlins as Secretary of War.[289] Washburne was replaced by conservative New York statesman Hamilton Fish.[289] Rawlins died in office after serving only a few months, replaced by William W. Belknap of Iowa.[290] For Treasurer he appointed Alexander T. Stewart who was found ineligible and replaced by Representative George S. Boutwell, a Massachusetts Radical Republican.[291] Philadelphia businessman Adolph E. Borie was appointed Secretary of Navy, who was reluctant to accept, soon resigned due to poor health and was replaced by a relative unknown, George M. Robeson, a former brigadier general.[292] Other cabinet appointments included former major general and Ohio Governor Jacob D. Cox for Secretary of the Interior, former Senator from Maryland John Creswell as Postmaster General, and Ebenezer Rockwood Hoar (Attorney General), all of whom were well received.[293]

Grant nominated Sherman his Army successor as general-in-chief and gave him control over war bureau chiefs.[294] When Rawlins took over the War Department,[lower-alpha 21] he complained to Grant that Sherman was given too much authority. Grant reluctantly revoked his own order, upsetting Sherman and damaging their wartime friendship.[294] Grant's nomination of James Longstreet, a former Confederate general, to the position of Surveyor of Customs of the port of New Orleans, was met with general amazement, and was largely seen as a genuine effort to unite the North and South.[296]

Grant also appointed four Justices to the Supreme Court: William Strong, Joseph P. Bradley, Ward Hunt and Chief Justice Morrison Waite.[297] Hunt voted to uphold Reconstruction laws while Waite and Bradley did much to undermine them.[298] To rectify his controversial General Order # 11 during the Civil War, Grant appointed Jewish leaders to office, including Simon Wolf recorder of deeds in Washington D.C., Edward S. Salomon Governor of the Washington Territory.[299] Grant integrated the executive mansion, appointed African Americans to federal positions and office, including Ebenezer D. Bassett minister to Haiti, and James Milton Turner minister to Liberia.[300]

Later Reconstruction and civil rights

When Grant took office in 1869, Reconstruction took precedence, Republicans controlled most Southern states, propped up by Republican controlled Congress, northern money, and southern military occupation.[301] Grant advocated in his inaugural address the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment that declared the right to vote for African Americans.[302] Unlike Johnson, Grant's vision of Reconstruction included federal enforcement of civil rights and spoke out against voter intimidation of Southern blacks.[303] Within a year, three remaining former Confederate states—Mississippi, Virginia, and Texas—were admitted to Congress, having complied with Congressional Reconstruction Acts and adopted the Fifteenth Amendment.[304] Supported by Congress, Grant put military pressure on Georgia, the last remaining former Confederate state, to reinstate its black legislators and adopt the new amendment.[305] Georgia complied, and on February 24, 1871 its Senators were seated in Congress.[306] Southern Reconstructed states were controlled by carpetbaggers, scalawags and former slaves. The Ku Klux Klan terrorist group, however, continued to undermine Reconstruction by violence and intimidation.[307]

Grant, in 1870, signed legislation creating the Justice Department. He employed it to enforce the Reconstruction efforts in the South.[308] On March 23, 1871, Grant asked Congress for legislation, passed on April 20, known as the Ku Klux Klan Act, that authorized the president to impose martial law and suspend the writ of habeas corpus.[309] By October, Grant suspended habeas corpus in part of South Carolina and sent federal troops to help marshals, who initiated prosecutions.[310] Grant's new Attorney General, Amos T. Akerman, a former Confederate officer and now zealous civil rights attorney from Georgia, replaced Hoar. Bolstered by the Department of Justice and Solicitor General, he made hundreds of arrests while forcing 2,000 Klansmen to flee the state. Akerman returned over 3,000 indictments of the Klan throughout the South and obtained 600 convictions for the worst offenders.[311] By 1872 the Klan's power had collapsed, and African Americans voted in record numbers in elections in the South.[312] That same year, Grant signed the Amnesty Act, which restored political rights to former Confederates. Lacking sufficient funding, the Justice Department stopped prosecutions of the Klan by June 1873. Civil rights prosecutions continued but with fewer yearly cases and convictions.[313] Grant's Postmaster General John Creswell used his patronage powers to integrate the postal system and appointed a record number of African American men and women as postal workers across the nation, while also expanding many of the mail routes.[314] Grant appointed Republican abolitionist and champion of black education Hugh Lennox Bond as U.S. Circuit Court judge.[315]

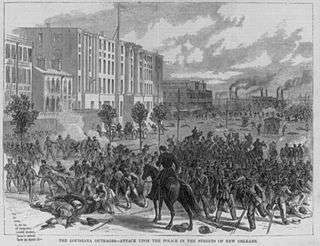

After the Klan's decline, a faction of southern conservatives called "Redeemers" formed armed groups, such as the Red Shirts and the White League, who openly used violence, intimidation, voter fraud, and racist appeals in an attempt to take control of state governments.[316] The Panic of 1873 and the ensuing depression contributed to public fatigue, and the North grew less concerned with Reconstruction.[317] Supreme Court rulings in the Slaughter-House Cases and United States v. Cruikshank restricted federal enforcement of civil rights.[318] In 1874, Grant ended the Brooks–Baxter War, bringing Reconstruction in Arkansas to a peaceful conclusion. That same year, he sent troops and warships under Major General William H. Emory to New Orleans in the wake of the Colfax Massacre and disputes over the election of Governor William Pitt Kellogg.[319] Grant recalled Sheridan and most of the federal troops from Louisiana.[320]

By 1875, Redeemer Democrats had taken control of all but three Southern states. As violence against black Southerners escalated once more, Attorney General Edwards Pierrepont told Governor Adelbert Ames of Mississippi that the people were "tired of the autumnal outbreaks in the South", and declined to intervene directly, instead sending an emissary to negotiate a peaceful election.[321] Grant later regretted not issuing a proclamation to help Ames, having been told Republicans in Ohio would bolt the party if Grant intervened in Mississippi.[322] Grant told Congress in January 1875 he could not "see with indifference Union men or Republicans ostracized, persecuted, and murdered."[323] Congress refused to strengthen the laws against violence, but instead passed a sweeping law to guarantee blacks access to public facilities.[324] Grant signed it as the Civil Rights Act of 1875, but enforcement was weak and the Supreme Court ruled the law unconstitutional in 1883.[325] In October 1876, Grant dispatched troops to South Carolina to aid Republican Governor Daniel Henry Chamberlain.[326] Grant's successor, Rutherford B. Hayes, abandoned the remaining three Republican governments in the South that were supported by the army after the Compromise of 1877, which marked the end of Reconstruction.[327]

In 1875, Grant proposed measures to limit religious roles in public schools. Grant laid out his agenda for "good common school education." He attacked government support for "sectarian schools" run by religious organizations, and called for the defense of public education "unmixed with sectarian, pagan or atheistical dogmas." Grant declared that "Church and State" should be "forever separate." Religion, he said, should be left to families, churches, and private schools devoid of public funds.[328] His views were incorporated into the Blaine Amendment. That amendment did not become federal law but many states adopted versions. Historian Tyler Anbinder says, "Grant was not an obsessive nativist. He expressed his resentment of immigrants and animus toward Catholicism only rarely. But these sentiments reveal themselves frequently enough in his writings and major actions as general....In the 1850s he joined a Know Nothing lodge and irrationally blamed immigrants for setbacks in his career."[329]

Indian peace policy

When Grant took office in 1869, the nation's policy towards Indians was in chaos, with more than 250,000 Indians being governed by 370 treaties.[72] He appointed Ely S. Parker, a Seneca Indian, a member of his wartime staff, as Commissioner of Indian Affairs, the first Native American to serve in this position, surprising many around him.[330][lower-alpha 22] In April 1869, Grant signed a law establishing an unpaid Board of Indian Commissioners to reduce corruption and oversee implementation of Indian policy, based on the appointment of Quakers as Indian agents.[332][lower-alpha 23] In 1871, he signed a bill ending the Indian treaty system; the law now treated individual Native Americans as wards of the federal government, and no longer dealt with the tribes as sovereign entities.[334][lower-alpha 24] Parker's resignation in 1871 undermined the peace policy, as did denominational infighting and entrenched economic interests, while Indians refused to adopt European American culture.[335]

On October 1, 1872, General Oliver Otis Howard successfully negotiated peace with Apache leader, Cochise, who waged guerrilla war against the army and settlers, to move the tribe to a new reservation.[336] On April 11, 1873, General Edward Canby, was killed in Northern California south of Tule Lake by Modoc leader Kintpuash, in a failed peace conference to end the Modoc War, shocking the nation.[337] Grant ordered restraint after Canby's death, the army captured Kintpuash, who was convicted of Canby's murder and hanged on October 3 at Fort Klamath, while the remaining Modoc tribe was relocated to the Indian Territory.[337] In 1874, the army defeated the Comanche Indians at the Battle of Palo Duro Canyon.[338] Their villages were burned and horses slaughtered, eventually forcing them to finally settle at the Fort Sill reservation in 1875.[339] Grant pocket-vetoed a bill in 1874 protecting bison and supporting Interior Secretary Columbus Delano, who believed correctly the killing of bison would force Plains Indians to abandon their nomadic lifestyle.[340][lower-alpha 25]

After discovery of gold in the Black Hills, miners encroached on Sioux land guaranteed under the Fort Laramie treaty.[342] Grant believed he could not keep the miners out, so he offered the Sioux $6,000,000 for their sacred lands in October 1874; Red Cloud reluctantly entered negotiations, but other Sioux chiefs readied for war.[343] On November 3, 1875, Grant held a meeting at the White House and, under advice from Sheridan, Grant agreed not to enforce keeping out miners from the Black Hills, and to force "hostile" Indians onto the Sioux reservation.[344][lower-alpha 26] During the Great Sioux War that started after Sitting Bull refused to relocate to agency land, warriors led by Crazy Horse killed George Armstrong Custer and his men at the Battle of the Little Big Horn, the army's most famous defeat in the Indian wars. Later, Grant castigated Custer in the press, saying "I regard Custer's massacre as a sacrifice of troops, brought on by Custer himself, that was wholly unnecessary – wholly unnecessary."[346] In September and October 1876, Grant convinced the tribes to relinquish the Black Hills. Congress ratified the agreement three days before Grant left office in 1877.[347][lower-alpha 27][lower-alpha 28]

Foreign affairs

The most pressing problem confronting Grant when he took office in 1869 was the settlement of the Alabama claims against Great Britain, involving a set of complex grievances and depredations committed against American shipping during the Civil War by the Confederate cruiser CSS Alabama, secretly purchased in England.[351] Senator Charles Sumner, Chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, believed the British had violated American neutrality and demanded reparations, including the acquisition of Canada.[352] Secretary of State Hamilton Fish and Treasurer George Boutwell convinced Grant that peaceful relations with Britain were more important, and the two nations agreed to negotiate along those lines.[353] To avoid jeopardizing negotiations, Grant refrained from recognizing Cuban rebels who were fighting for independence from Spain, which would have been inconsistent with American objections to the British granting belligerent status to Confederates.[354][lower-alpha 29] A commission in Washington produced a treaty whereby an international tribunal would settle the damage amounts; the British admitted regret, but not fault.[355][lower-alpha 30] The Senate approved the Treaty of Washington, which settled disputes over fishing rights and maritime boundaries, by a 50–12 vote, signed on May 8, 1871.[357]

Grant's settlement of the Alabama claims was undermined by his attempt to annex the Dominican Republic.[354] In early April 1869, Colonel Joseph W. Fabens, emissary for President Buenaventura Báez, met with Fish and presented a lavish proposal for Dominican Republic annexation.[358] On April 6, Fish brought up Dominican cession at a cabinet meeting, but the matter was passed by.[359] In July, Grant sent Babcock to the Dominican Republic given instructions by Fish to investigate the government, natural resources, people, and economy, without diplomatic authority to negotiate an annexation treaty.[360] In mid-September, Babcock returned to Washington with a controversial annexation treaty proposal, which Grant endorsed at a cabinet meeting, but informed his cabinet it was without diplomatic authorization.[361][lower-alpha 31]

Grant believed annexation would strengthen American strategic power in the Caribbean, increase natural resources, and serve as a safe haven for African Americans.[363] Fish was instructed by Grant to draw up two treaties, one for Dominican annexation and another for the lease of Samaná Bay.[364] In early January 1870, Grant visited Senator Sumner's home to gain his support for annexation. When Grant left, he was confident he had Sumner's approval, but he was wrong; the episode led to hostility between the two men. On January 20, Grant submitted the treaties to the Senate for ratification.[365]

After much stalling by Sumner, who opposed annexation, the Foreign Relations Committee rejected the treaties by a 5-to-2 vote. Grant personally lobbied senators, but despite his efforts the Senate defeated the treaties by a 28–28 vote with 19 Republicans joining the opposition.[366] Undaunted, Grant convinced Congress to send a commission to investigate.[367] For this undertaking, he chose three neutral parties, with Fredrick Douglass to head the commission.[368] Although the commission approved its findings, the Senate remained opposed, forcing Grant to abandon further efforts.[369] Grant fired Sumner's friend and Minister to Great Britain, John Lothrop Motley, while his allies in the Senate deposed Sumner of his chairmanship.[370]

In October 1873, Grant's Caribbean neutrality policy was shaken when a Spanish cruiser captured a merchant ship, Virginius, flying the U.S. flag, carrying supplies and men to aid the Cuban insurrection.[371] Spanish authorities executed the prisoners, including eight American citizens, and many Americans called for war with Spain.[372] Grant ordered U.S. Navy Squadron warships to converge on Cuba, off of Key West, supported by the USS Kansas.[373] On November 27, Fish reached a diplomatic resolution in which Spain's president, Emilio Castelar y Ripoll, expressed his regret, surrendered the Virginius and surviving captives.[374] A year later, Spain paid a cash indemnity of $80,000 to the families of the executed Americans.[375] Realizing the Navy was susceptible to European naval powers, in June 1874, Secretary Robeson commissioned the reconstruction of five redesigned double-turreted monitor warships.[376] In December 1874, Grant held a state dinner at the White House for the King of Hawaii, David Kalakaua, who was seeking duty-free sugar importation to the US. Grant and Fish secured a free trade treaty in 1875 with the Kingdom of Hawaii, incorporating the Pacific islands' sugar industry into the United States' economic sphere.[377]

Gold standard and the Gold Ring

Soon after taking office Grant took conservative steps to return the nation's currency to a more secure footing.[354] During the Civil War, Congress had authorized the Treasury to issue banknotes that, unlike the rest of the currency, were not backed by gold or silver. The "greenback" notes, as they were known, were necessary to pay the unprecedented war debts, but they also caused inflation and forced gold-backed money out of circulation; Grant was determined to return the national economy to pre-war monetary standards.[378] On March 18, 1869, he signed the Public Credit Act of 1869 that guaranteed bondholders would be repaid in "coin or its equivalent", while greenbacks would gradually be redeemed by the Treasury and replaced by notes backed by specie. The act committed the government to the full return of the gold standard within ten years.[379] This followed a policy of "hard currency, economy and gradual reduction of the national debt." Grant's own ideas about the economy were simple and he relied on the advice of wealthy and financially successful businessman that he courted.[354]

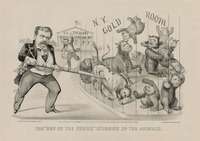

In April 1869, financial speculators Jay Gould and Jim Fisk plotted to corner the gold market in New York, the nation's financial capital.[380] Gould controlled the Erie Railroad, and a high price of gold would allow foreign agriculture buyers to purchase exported agriculture crops, shipped east over the Erie's routes, to reap Gould high returns.[381] Gould and Fisk planned to buy and bid up the price of gold in New York and make huge profits, but Boutwell's bi-weekly policy of selling gold from the Treasury kept gold artificially low.[382] To stop the sale of Treasury gold, Gould coddled a relationship with Grant's brother-in-law, Abel Corbin, and gained access to Grant.[383] Corbin and Gould lobbied for and convinced Grant to appoint Gould's associate, Daniel Butterfield, as Assistant Treasurer, allowing Butterfield to gather inside information for the Ring.[384] In mid-June, Gould personally lobbied Grant that a high price of gold would spur the economy and increase agriculture sales.[385]

In July, Grant reduced the sale of Treasury gold to $2,000,000 per month and subsequent months.[385] Fisk played a role in August in New York, having a letter from Corbin, he told Grant his gold policy would destroy the nation.[386] By September, Grant, who was naive in matters of finance, was convinced that a low gold price would help farmers, and the sale of gold for September was not increased.[387] On September 23, when the gold price reached 143 1⁄8, Boutwell rushed to the White House and talked with Grant.[388] The following day, September 24, known as Black Friday, Grant ordered Boutwell to sell, whereupon Boutwell wired Butterfield in New York, to sell $4,000,000 in gold.[389] The bull market at Gould's Gold Room collapsed, the price of gold plummeted from 160 to 133 1⁄3, a bear market panic ensued, Gould and Fisk fled for their own safety, while severe economic damages lasted months.[390] By January 1870, the economy resumed its post-war recovery.[391] An 1870 Congressional investigation chaired by James A. Garfield cleared Grant of profiteering, but excoriated Gould and Fisk for their manipulation of the gold market and Corbin for exploiting his personal connection to Grant.[392]

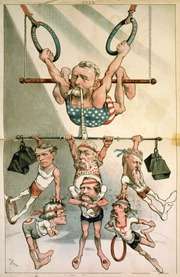

Election of 1872 and second term

Despite his administration's scandals, Grant continued to be personally popular.[393] His reelection was supported by Frederick Douglass and other prominent abolitionists along with reformers of the Indian question.[394] In 1871, to placate reformers and alleviate a burgeoning federal bureaucracy, Grant created the Civil Service Commission, chaired by reformer George William Curtis, authorized and funded by Congress, to take effect January 1, 1872.[395] Congress, however, failed to enact permanent civil service legislation and in 1875 it refused to implement funding to maintain the commission.[396] Party reformers cooled toward Grant, critical of Grant's implementation of the commission's proposed reforms, corruption at the New York Customs House investigated by Congress, and Grant's alliance with party and patronage boss New York Senator Roscoe Conkling.[397] There was further intraparty division between the faction most concerned with the plight of the freedmen, and the faction concerned with the growth of industry and small government. During the war, both factions' interests had aligned, and in 1868 both had supported Grant. As the wartime coalition began to fray, Grant's alignment with the party's pro-Reconstruction elements alienated party leaders who favored an end to federal intervention in Southern racial issues.[398]