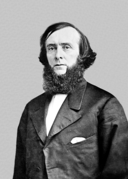

Orville E. Babcock

| Orville Elias Babcock | |

|---|---|

Orville E. Babcock | |

| Born |

December 25, 1835 Franklin, Vermont |

| Died |

June 2, 1884 (aged 48) Mosquito Inlet, Florida |

| Place of burial | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Allegiance |

United States of America Union |

| Service/ |

United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1861–1884 |

| Rank |

|

| Unit | United States Army Corps of Engineers |

| Battles/wars | |

| Other work | Private Secretary for President Ulysses S. Grant (1869–1877) |

Orville Elias Babcock (December 25, 1835 – June 2, 1884) was an engineer, and American Civil War general in the Union Army. An aide to General Ulysses S. Grant during and after the war, he was President Grant's private secretary at the White House, Superintendent of Buildings and Grounds for Washington D.C., and a Florida-based federal inspector of lighthouses. Babcock continued to serve as lighthouse inspector under Grant's successors Rutherford B. Hayes, James A. Garfield, and Chester A Arthur.

A native of Vermont, Babcock graduated third in his class at West Point in 1861, and served in the United States Army Corps of Engineers throughout the Civil War. As Assistant Engineer and aide-de-camp for district commander Nathaniel P. Banks, in 1862 Babcock worked on fortifications to aid in defending the nation's capitol from Confederate attack. Babcock later served as aide-de-camp for Ulysses S. Grant and participated in the Overland Campaign. He was promoted to brevet brigadier general in 1865 and continued on Grant's staff during Reconstruction. In 1867, Babcock warned Grant of a white supremacist insurgency that used Confederate symbolism to intimidate blacks in the South.

After Grant became President in 1869, Babcock was assigned Grant's Secretary to the President of the United States—in modern terms, the chief of staff—and he served until his departure from the White House in 1876. Babcock's salary was paid by the U.S. Army and he was not subject to Congressional approval. Grant also appointed Babcock Superintendent of Public Buildings and Grounds for Washington, DC. Babcock, at the time, was young and ambitious, and considered the Iago of the Grant administration. In 1869, Grant sent Babcock on a mission to explore the possibility of annexing the island nation of Santo Domingo to the United States, but the Senate led by Charles Sumner rejected the proposal.

Babcock's tenure under President Grant was embroiled in corruption charges, and his manipulation of both cabinet departments and appointments. Grant supported Babcock when Babcock was accused of corruption; Grant's shielding of Babcock from political attack stemmed primarily from their shared experiences on the battlefield during the American Civil War.[1] When Babcock was indicted as a member of the Whiskey Ring in 1875, Grant believed it was an indictment on his presidency. He provided a written deposition on Babcock's behalf—a first for a sitting president—which was admitted at Babcock's 1876 trial and resulted in his acquittal. The news coverage of the Whiskey Ring and other Grant administration scandals caused public opinion to turn against Babcock. Upon his return from St. Louis, Babcock was reluctant to leave his post, as if nothing happened, but under pressure from Secretary Fish, Grant forced Babcock to leave the White House.

President Grant would not desert his wartime comrade; in February 1877, he appointed Babcock Inspector of Lighthouses for the Federal Lighthouse Board's Fifth District, a low-profile post that did not attract undue public attention. In 1882, President Chester A. Arthur additionally appointed Babcock Inspector of Lighthouses for the Federal Lighthouse Board's Sixth District. Babcock was the chief engineer overseeing plans for the construction of Mosquito Inlet Lighthouse. He died in 1884 on duty when he drowned off Mosquito Inlet in Daytona Beach, Florida. Babcock's historical reputation is mixed; his technical engineering expertise, efficiency, bravery in battle, and Union loyalty were offset by his involvement in corruption, deception, and scandal. Uncommon for his times, Babcock showed no racism in relations with African Americans or mixed race peoples, which was a key factor in Grant's decision to send Babcock to Santo Domingo, whose population was predominantly mixed race, and consisted of individuals with American Indian, African, and Hispanic ancestry.

Early life

Orville E. Babcock was born on December 25, 1835 in Franklin, Vermont, a small town located near the Canada–US border close to Lake Champlain. Babcock's father was Elias Babcock Jr. and his mother was Clara Olmsted.[1] While growing up in Vermont he received a common education.[2] At the age of 16, Babcock was appointed to the West Point Military Academy (USMA), where he graduated third in a class of 45 on May 6, 1861.[2] His high class ranking enabled Babcock to select his branch, and he chose the Engineers, as did most top graduates of his era.[3][4]

Civil War (1861–1865)

Constructed Washington D.C. defense works

The American Civil War was beginning as Babcock was graduating; he was commissioned as a Brevet Second Lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers, and assigned to duty as an Assistant Engineer for the military district that included Washington. His first mission was the undertaking of efforts to improve the defensive works of Washington, D.C. and protect the city from attack.[1] On July 13, 1861, Babcock was assigned to the Department of Pennsylvania.[1] In August, he received his commission as a second lieutenant, to date from his West Point graduation in May; he was assigned to the Department of the Shenandoah, and constructed military fortifications on the Potomac River and in the Shenandoah Valley while also serving as aide-de-camp under Major General Nathaniel P. Banks.[1] From August through November, Babcock worked again on improving the fortifications surrounding Washington, responding to increased apprehension the Union capital was vulnerable to attack and capture by the Confederate Army.[2]

Peninsular campaign

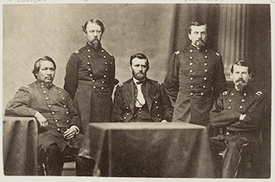

and Orlando M. Poe (right),

Union Engineers in Ft. Sander's salient. Photograph by Barnard, 1863–1864.

On November 17, 1861, Babcock was promoted to First Lieutenant, Corps of Engineers, and a week later was assigned to the Army of the Potomac.[2] During the months of February and March, 1862, while General Banks moved to Winchester, Virginia, Babcock set up military fortifications at Harper's Ferry and guarded pontoon bridges crossing the Potomac River.[2] During the Peninsular Campaign, Babcock served bravely at the Siege of Yorktown with the Army of the Potomac's Engineer Battalion and was breveted as a captain to rank from May 4, 1862.[2] For the next seven months, Babcock built bridges, roads, and field works. For his service, in November, 1862, Babcock was promoted to Chief Engineer Left Grand Division of the Army of the Potomac.[2]

In December 1862, during the Battle of Fredericksburg, Babcock served on Brigadier General William B. Franklin's engineering staff.[1]

Vicksburg, Blue Springs, Campbell's Station

On January 1, 1863, Babcock was promoted to permanent captain and brevet lieutenant colonel, and was named the Assistant Inspector General of the VI Corps until February 6, when he was named the Assistant Inspector General and Chief Engineer of the IX Corps.[2] As Chief Engineer of the IX Corps, Babcock surveyed and projected the defensive fortifications at Louisville and Central Kentucky.[2] Moving westward to help secure the Mississippi River from Confederate control and divide the Confederacy in two, Babcock fought with the IX Corps at the Battle of Vicksburg and the Battle of Blue Springs, and the Battle of Campbell's Station.[2]

Knoxville campaign

After fighting in the Knoxville Campaign, at the Battle of Fort Sanders, he became the Chief Engineer of the Department of the Ohio and promoted to Brevet Major on November 29, 1863.[2]

Overland Campaign

Babcock was promoted to lieutenant colonel in the regular army on March 29, 1864 and became the aide-de-camp to Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant participating in Overland Campaign against General Robert E. Lee and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia.[5] Babcock served in the Battle of the Wilderness, the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, and the Battle of Cold Harbor.[2]

For his gallant service at the Battle of the Wilderness, Babcock was appointed brevet lieutenant colonel, U.S. Volunteers, to rank from May 6, 1864.[6] On August 9, 1864, Babcock, while stationed at Union headquarters in City Point, was wounded in the hand after Confederate spies had blown up an ammunition barge moored below the city's bluffs.[7] As Grant's aide-de-camp, Babcock ran dispatches between Grant and Major General William T. Sherman during Sherman's March to the Sea campaign.[2]

Appomattox: Lee surrenders to Grant

On April 9, 1865 after being defeated at the Battle of Appomattox, Commanding Confederate General Robert E. Lee formally surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia to Ulysses S. Grant. Babcock personally chose the site of surrender at the McLean House,[2] personally escorted Lee to the meeting,[2] and witnessed Grant and Lee discussing and signing the surrender terms.[2]

For his meritorious contributions in the Civil War, Babcock was appointed brevet colonel, to rank from March 13, 1865.[6] On July 17, 1866, President Andrew Johnson nominated Babcock for brevet brigadier general in the regular army, to rank from March 13, 1865, and the United States Senate confirmed the appointment on July 23, 1866.[8]

Reconstruction

Final promotions, marriage, and family

_ELEVATION%2C_VIEW_EAST_ON_G_STREET._-_Orville_E._Babcock_House%2C_Washington%2C_District_of_Columbia%2C_DC_HABS_DC%2CWASH%2C396-3.tif.jpg)

After the War, Babcock remained on Grant's staff throughout America's turbulent Reconstruction Period. On July 25, 1866, Brig. Gen. Babcock was commissioned Colonel of Staff and aide-de-camp for General-in-Chief of the Army, Ulysses S. Grant.[2][9] On March 21, 1867 Babcock received a Regular Army commission as a major in the Corps of Engineers.[2][9]

On November 6, 1866, Babcock married Anne Eliza Cambell in Galena, Illinois.[10] Their marriage produced four children: Campbell E. Babcock, Orville E. Babcock, Jr., Adolph B. Babcock, and Benjamin Babcock. Benjamin died during infancy.[11] Babcock moved to Washington D.C. to serve under Grant while Grant was Commanding General and President of the United States.

Reported on South (1867)

In mid-April Commanding General Grant dispatched Babcock and Horace Porter, another member of Grant's staff, to report on the progress of Southern Reconstruction.[12] Babcock and Porter were optimistic on the plight of blacks who had embraced citizenship saying the "negro is learning very fast. They will soon be the best educated class in the South, if they continue at their present rate of progress."[12] However, Babcock discovered and informed Grant of a white supremacist insurgency and Confederate symbolism were developing that intimidated African Americans, saying that in Georgia the "police in most of the cities are in a grey uniform, the real confederate uniform."[12]

President Grant's military secretary (1869–1876)

In 1868, Ulysses S. Grant was elected the 18th President of the United States. In 1869, General Babcock was assigned Grant's military private secretary.[13] Babcock worked directly for President Grant. Babcock, one of a few men who had daily access to President Grant at the White House, had unprecedented influence over President Grant and planted suspicions in Grant that enemies were out to politically destroy his administration. His influence even extended indirectly into many cabinet departments and he was at odds with reformers, that included Secretary Fish and Secretary Bristow, who both had desired to save Grant's reputation from scandal. When cabinet appointments came available, Grant listened to Babcock's recommendations.[14] Babcock, who was admired by Grant for his Civil War service, was young and ambitious and considered the Iago of the Grant administration.[15]

Gatekeeper to Grant

Babcock was 33 years old at the time of Grant's inauguration.[16] He retained his position in the U.S. Army under Sherman, who under special arrangement with Grant was allowed to be the President's personal secretary.[17] Babcock did not require Senate confirmation for his appointment, while he retained his military salary.[17] Babcock's duties included involvement in patronage matters, finding dirt on Grant's administration critics, and feeding political stories to pro-Grant newspapers.[16]

Babcock's office was in an anteroom on the second floor of the White House that led to President Grant's private office.[9] In order to see Grant, visitors had to go through Babcock,[9] a circumstance that caused many to resent Babcock's insider role, and created a negative perception among contemporaries that overrode Babcock's positive attributes.[9] Babcock also opened and answered most of Grant's personal letters,[9] and historian Allan Nevins argued that Babcock's position was as at least as important as the Cabinet secretaries, and more powerful than most.[9]

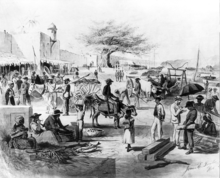

Santo Domingo annextation (1869-1871)

After his appointment, in 1869, Babcock was involved as a special agent of President Ulysses S. Grant in the attempt to annex the mostly black Caribbean island country of the Dominican Republic (18,655 mi²), then commonly called Santo Domingo.[18] At this time, federal land speculation was not uncommon, as Congress had in March 1867, purchased Alaska (663,300 mi²) from the Russian Empire.[19] Like his predecessor, Andrew Johnson, Grant received inducements for Caribbean expansion particularly for Haiti and the Dominican Republic.[20] Speculators William L. Cazneau and Joseph W. Fabens formed the Santo Domingo Company in New York to gain investment backers for the annexation of the Dominican Republic.[20] Grant's Secretary of State Hamilton Fish, was doubtful concerning Haitian annexation, believing the country to unstable, but he was initially more favorable to annexing the Dominican Republic after realizing investors were highly enthusiastic towards investing in the country.[20] Fish, however, became suspicious of annexation when Fabens, representing promoters, approached Fish and asked him to support a plan of American annexation of the Dominican Republic.[18] Grant, who was more favorable to wealthy business leaders and investors, supported annexation.[18] Fish, supporting Grant out of loyalty, agreed to send Babcock on a reconnaissance mission, Grant's appointed special agent to the Dominican Republic.[21]

Babcock was accompanied by Fabens and annexation supporter California Republican Senator Cornelius Cole.[18] Cazneau, who was on the island, formerly introduced the young and ambitious Babcock to the Dominican Republic President Buenaventura Báez, and the two unknown to Fish, made a draft of annexation.[22] According to the annexation draft made in September 1869, Samaná Bay would be sold to the United States for $2 million or the country would be annexed to the United States after paying of the Dominican Republic's national debt of $1.5 million.[22] Babcock was a supporter of Congressional Reconstruction, and he saw Santo Domingo, not as a nation of blacks, but as a source of new opportunities in a post war world.[23]

When Babcock returned to the White House having a treaty, Fish and Secretary of Interior Jacob D. Cox were alarmed, since Babcock had no official standing.[24] Fish told Cox, "Babcock is back...I pledge you my word he had no more diplomatic authority than any other casual visitor to the island."[24][25] At the next cabinet meeting Babcock was there in person and Grant told his silenced cabinet that Babcock was back and that he approved of the treaty, while it only needed a signature from the U.S. consular in Santo Domingo.[26] Cox spoke up and said, " But Mr. President, has it been settled, then, that we want to annex Santo Domingo ?" Grant was embarrassed and began puffing on his cigar, while the other cabinet members said nothing, Cox's question remained unanswered.[27] Fish threatened to resign over the matter, but Grant convinced him to stay on the administration telling Fish he would not go around him again and he needed Fish's guidance and support.[27] Fish agreed to remain on the cabinet, although he hoped Grant would drop the Santo Domingo annexation treaty.[27]

Grant, however, did not drop the treaty, having believed annexation would help alleviate violent suppression of African Americans in the Southern states, as blacks would have a safe environment to work and live, in the Dominican Republic. Fish sent Babcock back to the Dominican Republic on November 18, accompanied by Quartermaster Rufus Ingalls, this time having official State Department status and instructions to draw up two formal treaties, signed on November 29, 1869.[28] Grant, however, kept the treaties secret from Congress and the public, until mid-January 1870.[18] After earnest public discussion, the treaties was formerly submitted to Congress in March, whereupon Senators joined in the debate.[18] Senator Charles Sumner strongly opposed the annexation treaties objecting to Babcock's secret negotiations, his use of naval power, and desiring to keep Santo Domingo an autonomous African American nation rather than annexation and potential statehood as Grant had proposed. The people of Santo Domingo overwhelmingly desired annexation voting 15,169 to 11 in its favor, according to a plebiscite held by Báez.[21] Senate Republicans led by Sumner split the party over the treaty while Senators loyal to Grant supported the treaty and admonished Babcock. The treaties however failed to pass the Senate causing continued bitterness and hostility between Grant and Sumner, both stubbornly trying to control the Republican Party. Although Babcock was suspected of being given investment land on Samaná Bay, a Congressional investigation found no conclusive evidence that Babcock would financially gain from the country's annexation.[29] Babcock in the minority report was criticized for acquiescing in the imprisonment of Davis Hatch, an American abroad, who was an open critic of Báez.[30]

Gold corner (September 1869)

In 1869, Babcock invested money in the Jay Cooke & Company's Gold Ring, a scam by wealthy New York tycoons Jay Gould and James Fisk to profit by cornering the market on gold.[31] Starting in late April, Secretary of the Treasury George S. Boutwell had regulated the price of gold by monthly sales from the Treasury in exchange for greenbacks.[32] As part of the Gold Ring's effort, Gould convinced Grant not to increase the Treasury's September gold sale, helping make it scarce and inflating the price.[33] Gould and Fisk then set up a buying operation, the New York Gold Room, where traders in their employ purchased as much gold as they could acquire, which artificially drove up the price.[34] When Grant became aware of the full extent of the attempt to corner the market in late September 1869, he ordered the release of $4,500,000 in Treasury gold, which caused the price to collapse.[31] Gould and Fisk were thwarted, but at the expense of a decline in the stock market and the overall economy.[31] Babcock and other individuals who secretly invested with him lost $40,000 (about $750,000 in 2018).[31], and to satisfy his creditors, Babcock had to sign a trust deed on his property, which named Asa Bird Gardiner as trustee.[35] The extent of Babcock's involvement was not revealed to Grant until 1876, when his complicity in the Gold Ring was uncovered during the investigation of his involvement in the Whiskey Ring.[36]

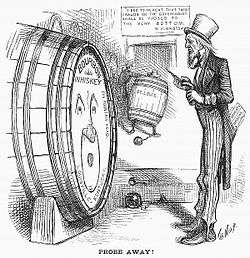

Corruption: Whiskey Ring (1875–1876)

Dating back to the Presidency of Abraham Lincoln it was common for distillers and corrupt Internal Revenue agents to make false whiskey production reports and pocket unpaid tax revenue.[37] However, during the early 1870s, the corruption became more organized by distillers, who used the illegally obtained money for bribery and illegal election financing, to the point where every agent in St. Louis was involved in corruption.[37] This organized network, known as the Whiskey Ring, extended nationally and involved "the printing, selling, and approving of forged federal revenue stamps on bottled whiskey."[38]

In June 1874, President Grant appointed Benjamin Bristow as Secretary of Treasury, with authority to investigate the Whiskey Ring and prosecute wrongdoers. Bristow, a Kentuckian and Union Army veteran, was known for his honesty and integrity, and had served as the nation's first Solicitor General, also appointed by Grant.[39] Bristow immediately discovered whiskey tax evasion among distillers and corrupt officials in the Treasury Department and the Internal Revenue Bureau.[40] Bristow and Bluford Wilson, the Treasury Solicitor obtained Grant's permission to use secret agents appointed from outside the Treasury Department; as a result of the evidence they obtained, on May 10, 1875 Treasury Department agents raided and shut down corrupt distilleries in St. Louis, Chicago, and Milwaukee, seizing company financial records and other files.[40]

Bristow then prosecuted the offenders by working with Grant's newly appointed Attorney General, Edwards Pierrepont, a popular New York reformer who had been involved in shutting down New York City's corrupt Tweed Ring.[40] Information was soon discovered that Babcock was informing ring leader John McDonald in St. Louis of inspections by Bristow's agents, giving them time to hide incriminating evidence before agents arrived.[41] Bristow believed Babcock was paid off by cash, two five-hundred-dollar bills, in one instance, hidden a inside cigar box, for this information and protection.[41] McDonald was indicted in June, when Bristow obtained indictments against 350 distillers and government officials.[41]

In July 1875, Bristow and Pierrepont met Grant, who was vacationing at Long Branch, and gave him evidence that Babcock was a member of the ring. [42] Grant told Pierrepont "Let no guilty man escape..." and said if Babcock was guilty then it was the "greatest piece of traitorism to me that a man could possibly practice."[41] In October, Babcock was summoned in front of Grant, Bristow, and Pierrepont at the White House to explain two ambiguously signed "Sylph" telegrams hand written by Babcock.[43] The first message said, "I have succeeded. They will not go. I will write you." (December 10, 1874) and the second one said, "We have official information that the enemy weakens. Push things." (February 3, 1875)[44] Bristow had shown these messages to Grant at a cabinet meeting the same day.[45] Babcock said something to Grant, unintelligible to Bristow and Pierrepont, and Grant appeared satisfied by Babcock's interpretation of the telegrams.[46]

Pierrepont and Bristow, believing the matter to be crucial, insisted Babcock send a message to his telegraphic correspondent demanding that this individual come to Washington to give his version of the messages.[47] After Babcock seemed to be taking too long, Pierrepont went to check on him and found Babcock writing a warning to revenue agent John A. Joyce, his St. Louis confederate, to be on his guard.[48] Infuriated, Pierrepont grabbed Babcock's pen and dashed through his message yelling "You don't want to send your argument; send the fact, and go there and make your explanation. I don't understand this."[47] Grant, on the other hand, was divided between the loyalty he had for Babcock, and his desire for Bristow and Pierrepont, trustworthy members of his cabinet, to prosecute the Whiskey Ring.[41] Since Babcock had no acceptable explanation for his messages, he was soon indicted November 4, 1875 for tax fraud.[49]

As a military officer, on December 2, 1875 Babcock requested of Grant a military court martial, believing that an army tribunal would be favorable to his defense.[50] On December 8, 1875, U.S. Attorney David Dyer followed Bristow's instructions to deny Babcock a court martial, setting his St. Louis jury trial for February, 1876.[45] When Babcock's trial in St. Louis came up in February, Grant decided to testify in Babcock's defense.[51] By this time, Grant said his critics were using Babcock to go after his own presidency.[45] After cabinet members objected to Grant testifying in St. Louis as unseemly for a President, it was settled that Grant would give a deposition at the White House.[51]

St. Louis Trial (February 1876)

Babcock's trial started on February 8, 1876 and would last eighteen days. Babcock's defense team included Grant's former Attorney General George Williams, a top criminal defence lawyer, Emory Storrs, and former appeals judge (New York), John K. Porter.[52] The trial was a sensational event and took place at the U.S. Post Office and Custom House, on 218 North Third Street, in St. Louis.[53] The people gathered at the courtroom door and on Third Street, but only persons who had passes or were indicted in the Whiskey Ring were allowed in. Before Babcock's trial, four prominent St. Louis gentlemen were put on trial and convicted for their involvement in the Whiskey Ring. Babcock was charged with his secret involvement and interference in the investigation of the Whiskey Ring. [53] Babcock came to the trial, in civilian clothes, dressed in sky-blue pants, donning a silk hat, and a light jacket. Away from the trial Babcock stayed at the newly rebuilt Lindell Hotel, on Sixth Street and Washington Avenue. [53]

Grant's White House deposition took place on February 12; it was notarized by Chief Justice Morrison Waite and witnessed by both Bristow and Pierrepont.[51] At the deposition Grant fully supported the Whiskey Ring prosecutions, but he willfully refused to testify against Babcock, despite having been informed by Bristow of Babcock's duplicity, saying he had "great confidence" in Babcock's integrity, and that his confidence in Babcock was "unshaken".[54] Grant's unprecedented testimony would prove to be devastating to for the Whiskey Ring prosecution team against Babcock.

On February 17, Babcock's defense read President Grant's powerful deposition that supported Babcock to the jury, and severely weakened any chance of Babcock being convicted.[53] The same day, General William T. Sherman, testified at the trial, that Babcock's "character has been very good."[53] Grant's deposition, Sherman's in-person tesitmony, and Babcock's shrewed defense counsel led to his acquittal by the St. Louis jury.[51] A rumor spread that Pierrepont had leaked information to Babcock that aided in his acquittal, but Pierrepont denied this and suggested that Babcock himself had started the rumor.[55] Emnity between Grant and Bristow, forced Bristow out of the cabinet, who resigned office on June 20, 1876.

Return to Washington D.C.

When Babcock returned to Washington, he went back to his White House office, as if there has been no trial. Grant's Secretary of State, Hamilton Fish, was furious, and pressured Grant to force Babcock to leave, saying that Grant merely had to dismiss Babcock, because he was a military officer. Additionally Grant had been informed by Solicitor Wilson that Babcock was involved with a plot to corner the gold market in September, 1869.[56] Grant finally dismissed Babcock from the White House, appointing his son Ulysses Jr. in Babcock's place.[51] It was later discovered Babcock had laundered Whiskey Ring kickbacks from distillers by purchasing a place and grove land in Crystal Lake, Florida on Christmas Day 1874.[57]

Superintendent of public buildings and grounds (1869–1877)

In addition to being Grant's private secretary Grant had appointed Babcock, a trained and experienced engineer, Superintendent of public buildings and grounds, that included public works in Washington D.C.[58] Babcock was involved in the beautification and improvement of Washington D.C., while his tenor was impressive, it was not free from scandal.[59] Babcock worked for Grant appointed Washington D.C. territorial governor Alexander Shepherd, who himself used aggressive and profitable methods that improved the infrastructure of the nation's capitol.[59] Babcock's supervision included the chain bridge over the Potomac River and the Anacosta bridge.[58] Babcock also supervised the construction of the east wing of the new state war and navy departments.[58] Babcock retained this position after he was dismissed by Grant from the White House as his private secretary in 1876, and kept the position until March 3, 1877, when the Grant administration ended.

Safe burglary conspiracy (1876)

Babcock was also named as a participant in the Safe Burglary Conspiracy.[60] In 1874, Richard Harrington, an Assistant United States Attorney for Washington, DC attempted to frame Columbus Alexander, leader of the Memorialists, an organization critical of Alexander Robey Shepherd's management of the city.[60][61] Richardson hired dishonest Secret Service agents to break into the U.S. Attorney's safe, using explosives to make it obvious that a burglary had occurred.[60] To entrap Alexander, the conspirators took materials that were supposedly stolen from the safe to his home at night, intending to give them to him and then latter arrest him for their possession. Alexander thwarted this effort by refusing to answer the door.[62][60] At that point, the Secret Service agents arrested two other conspirators who pretended to be the supposed burglars, and had them sign false affidavits implicating Alexander in the burglary.[60] The conspiracy collapsed when the Secret Service agents admitted at Alexander's trial that the charges were false, and Alexander was acquitted.[60] The conspiracy was supposed to have included Babcock, who was said to have wanted to silence Alexander, a prominent Grant administration critic.[60] Babcock was exonerated of direct involvement, but his continued ties to scandal and corruption increased public pressure on Grant to remove him from the White House.[63]

Inspector of lighthouses (1877–1884)

On February 27, 1877 President Grant appointed Babcock Inspector of Lighthouses of the Fifth District.[58][64] On August 24, 1882, President Chester A. Arthur Babcock appointed Inspector of Lighthouses for the Sixth District.[65][64] Babcock served under the next four presidents, Rutherford B. Hayes, James A. Garfield, and Arthur, under whom he headed both the Fifth and Sixth Lighthouse Districts.

Presidential election (1880)

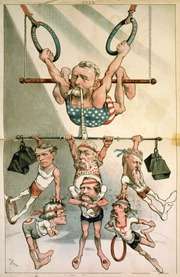

In September 1879, Grant had returned from his famous world tour, and was very popular around the country. There was talk among Stalwart Republicans that Grant be nominated for a third term presidential bid. Democrats were aware of Grant's national popularity and sought to discredit his two term presidency from 1869 to 1877, including his cabinet and political appointees. The following year, on February 4, 1880, prior to the Republican convention, in a color illustration by artist Joseph Keppler in the Democratic Puck magazine, Keppler ridiculed Grant and his associates while Grant was President, including Orville E. Babcock, for alleged involvement in corrupt rings.[66] Babcock was then serving as Inspector of Lighthouses under President Hayes, who had refused to run for a second term.

On May 14, 1880, Connecticut Democratic Senator William W. Eaton read a memorial to Davis Hatch, who in 1868, had been arrested and subject to the death penalty in Santo Domingo, that led to the charge that Babcock, when he was visiting the island nation in 1869 to secure an annexation treaty, interfered in his release.[67] Although Hatch's sentence was commuted to banishment, Hatch said he was imprisoned on false charges and Babcock was directly complicit in Hatch's five month prison term.[67] Republican Senator Roscoe Conkling defended Babcock, saying that the Senatorial investigation committee majority report had fully exonerated Babcock and that Eaton was bringing this issue up because it was an election year.[67]

In June 1880, the Republicans held their national convention in Chicago. Former President Ulysses S. Grant was nominated by his main Stalwart Republican backer Senator Roscoe Conkling, who had the previous month defended Babcock in the Senate. The Republicans had mixed feelings about Grant, and selected James A. Garfield as their presidential candidate. Chester A. Arthur was selected for the vice presidential nomination, and Garfield went on to win the general election, defeating Democratic nominee Winfield S. Hancock.

Mosquito Inlet lighthouse and drowning (1883–1884)

The Mosquito Inlet Lighthouse project started in 1883, and Babcock was the supervising engineer.[68][65] On June 2, 1884, Babcock and his associates were on duty were aboard the government schooner Pharos to deliver construction supplies, and were anxious to get to land because a sudden storm created hazardous ocean conditions.[65][68][64] The captain decided not to cross over the inlet bar during the storm because the construction supplies weighed down the ship. As the storm worsened, Captain Newins of another ship, the Bonito led seven men in a row boat to the Pharos in order to retrieve the passengers.[65] In debating whether to wait out the storm on the Pharos or try to make land, Babcock told his associates that since Newins and his crew had rowed safely to the Pharos, then they should be able to row to shore on tidal floods created by the storm.[65] After eating their lunch on the Pharos, Babcock and his associates boarded a rowboat and started for the shore. As they approached the inlet bar, the swells capsized the boat several times, and it took on water. Babcock was thrown clear, but another person on the boat attached him to it by a lifeline.[65] The boat and crew were battered by waves, oars, and other debris, and Babcock's lifeline was torn loose from the boat, which resulted in his drowning death. Upon reaching the shore, others who had been in the boat recovered Babcock's body and unsuccessfully tried to resuscitate him. Three others, including two of Babcock's associates, were also killed; the bodies of Babcock's associates, Levi P. Luckey and Benjamin F. Sutter, were recovered several days later, but the body of the fourth victim, a member of the boat's crew, was not found.[65][69] The lighthouse construction project continued after Babcock's death, and was completed in 1887.

Historical reputation

Scholars note Babcock's high class standing at West Point, engineering skills, and bravery during the American Civil War.[16] Babcock also has been noted positively for his association with the antislavery views of the Radical Republicans, and for his dealings with African Americans from a position of equality, a trait which was uncommon for the white people of his era, even those who opposed slavery. Historians also make positive mention of Babcock's post-White House career, noting that he served for eight years as a government lighthouse inspector and engineer, and did so capably and honestly.

However, historians are critical of Babcock's political power as Grant's White House military aide, shielded by Grant, and not subject to resignation.[70] Historians are also highly suspicious of Babcock's unauthorized Santo Domingo annexation pre-agreement. His reputation was also marred by his involvement in the Gold Ring, the Whiskey Ring, and the Safe Burglary Conspiracy. Most historians agree that Babcock betrayed Grant while President, and remain perplexed at Grant's loyalty to his wartime comrade, including Grant's unprecedented White House deposition on Babcock's behalf. In defending Babcock, Grant was not fully candid with the truth in his own testimony, probably to protect his family and his presidency from further scandal. With Babcock's reputation largely narrowed to observations about his corruption, loyalty to Grant, and wartime bravery, historians are generally not able to consider him in a wider context because he did not author an autobiography, nor has he been the subject of an extended biography. Historian William McFeely criticized Babcock for ignoring ethical values in the spirit of opportunism and personal gain.[23]

On November 22, 2016, Mississippi State University Libraries announced the digitalization of Babcock's private diaries.[71] Babcock's diaries are part of Mississippi State University Libraries Ulysses S. Grant's digital collection.[71] Babcock's diaries began in 1863 during the height of the American Civil War, including his perspective on the siege of Vicksburg and his wartime experiences in Kentucky, Ohio, Tennessee, and Virginia.[71] The diary collections also includes his famous post-war visit to Santo Domingo in 1869 serving as President Grant's special agent and personal secretary.[71] The collection includes Babcock's supplementary materials of speeches, correspondence, and newspaper clippings.[71] The Mississippi State University Libraries said that Babcock's brokerage of the annexation of Santo Domingo, "began what became a string of controversies and scandals surrounding Babcock and his position as aide to the President."[72] The scandals culminated in Babcock's involvement in the Whiskey Ring having been indicted for tax fraud in 1875 and put on trial in St. Louis 1876.[72] Throughout these scandals President Grant gave Babcock his confidence.[72]

According to presidential historian Charles W. Calhoun, Babcock emerged as Grant's "political majordomo, if not his jackel."[16] Grant's Secretary of State Hamilton Fish said Babcock "has brains & very many excellent & gentlemanly qualities but is spoiled by his position & a want of delicacy & consideration for the official responsibilities & proper authority (official) of civilians."[16]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dictionary of American Biography (1928), Babcock, Orville E., p. 460

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 New York Times (June 4, 1884) , Gen. Babcock Drowned

- ↑ Jones, Evan C.; Sword, Wiley (2014). Gateway to the Confederacy: New Perspectives on the Chickamauga and Chattanooga Campaigns, 1862-1863. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-8071-5512-7.

- ↑ Babcock, Stephen (1903). Isaiah Babcock, Sr. and his descendants. New York, NY: Eaton & Mains. p. 776.

- ↑ White 2016, p. xvii.

- 1 2 Eicher, John H.; Eicher, David J. (2001). Civil War High Commands. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

- ↑ Catton (1969), p. 349.

- ↑ Eicher, 2001, p. 732.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kirshner 1999, p. 133.

- ↑ Kirshner 1999, p. 132.

- ↑ Inventory of the Orville E. Babcock Papers (2008)

- 1 2 3 Chernow 2017, p. 588.

- ↑ Reeves, Thomas C. (1975). Gentleman Boss. NY, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 59. ISBN 0-394-46095-2.

- ↑ Woodward (1957), The Lowest Ebb

- ↑ Simon 2002, p. 249.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Calhoun 2017, p. 78.

- 1 2 Calhoun 2017, p. 77.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Pletcher 1998, p. 164.

- ↑ Chernow 2017, p. 661.

- 1 2 3 Pletcher 1998, p. 163.

- 1 2 Pletcher 1998, pp. 164-165.

- 1 2 Pletcher 1998, p. 164; White 2016, p. 508.

- 1 2 McFeely 1981, p. 340.

- 1 2 Brands 2012, p. 453.

- ↑ Pletcher 1998, p. 164; White, p. 508.

- ↑ Brands 2012, pp. 453-454.

- 1 2 3 Brands 2012, p. 454.

- ↑ Pletcher 1998, p. 164; White 2016, p. 509.

- ↑ McFeely 1974, p. 138; McFeely 1981, p. 343.

- ↑ McFeely 1974, p. 138.

- 1 2 3 4 Chernow 2017, p. 647.

- ↑ Calhoun 2017, p. 128.

- ↑ Chernow 2017, p. 647; Calhoun 2017, p. 134.

- ↑ Calhoun 2017, pp. 140-141.

- ↑ Knott 1876, p. 421.

- ↑ Simon The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant: January 1-October 31, 1876 , pages 47, 48

- 1 2 McFeely 1974, p. 154.

- ↑ Fredman (1987), The Presidential Follies

- ↑ White 2016, p. 556.

- 1 2 3 White 2016, p. 557.

- 1 2 3 4 5 White 2016, p. 562.

- ↑ White 2016, p. 562; McFeely 1974, p. 156.

- ↑ White 2016, p. 563; Brands 2012, p. 557; McFeely 1981, p. 410.

- ↑ Smith 2001, p. 591.

- 1 2 3 White 2016, p. 563.

- ↑ White 2016, p. 563; McFeely 1981, p. 410.

- 1 2 Brands 2012, p. 557; McFeely 1981, p. 411.

- ↑ McFeely 1981, p. 411.

- ↑ Brands 2012, p. 557.

- ↑ McFeely 1974, p. 157.

- 1 2 3 4 5 White 2016, p. 564.

- ↑ Calhoun 2017, p. 522.

- 1 2 3 4 5 O'neil 2017.

- ↑ White 2016, p. 564; Chernow 2010, p. 806.

- ↑ Reeves, Thomas C. (1975). Gentleman Boss. NY, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 80–81. ISBN 0-394-46095-2.

- ↑ Brands 2012, p. 560.

- ↑ Robison (Jan 6, 2002), Deeds, Letter Prove General's Ties to Sanford, Accessed on February 9, 2017

- 1 2 3 4 BDOA_1906.

- 1 2 Calhoun 2017, p. 527.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Coffey 2014, p. 282.

- ↑ McFeely 1974, pp. 139, 141-142.

- ↑ McFeely, pp. 141-142.

- ↑ Coffey 2014, p. 276.

- 1 2 3 Government Printing Office 1898, p. 224.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Garmon_2009.

- ↑ Michael Alexander Kahn, Richard Samuel West (October 2014), What Fools These Mortals Be!, p 49 --- Illustration by Joseph Keppler (February 4, 1880),Puck, v. 6, No. 152, pp. 782-783

- 1 2 3 New York Times (May 15, 1880).

- 1 2 Mike Pesca (November 2, 2005). "Orville Babcock's Indictment and the CIA Leak Case".

- ↑ "The Mosquito Inlet Disaster: Captain Anderson's Account of the Drowning of Gen. Babcock and Mr. Luckey". Washington Evening Star. Washington, DC. June 27, 1884. p. 4. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Calhoun 2017, pp. 78, 527.

- 1 2 3 4 5 MSU Libraries digitize Civil War diaries and letters.

- 1 2 3 Orville Babcock Diaries.

Sources

Books

- Annual Report of the Light-House Board of the United States to the Secretary of Treasury for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1898. Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1898.

- Brands, H. W. (2012). The Man Who Saved the Union: Ulysses S. Grant in War and Peace. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-53241-5.

- Rossiter Johnson, ed. (1906). Biographical Dictionary of America Orville E. Babcock. Boston: American Biographical Society.

- Calhoun, Charles W. (2017). The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 9780700624843.

- Chernow, Ron (2017). Grant. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1-5942-0487-6.

- Coffey, Walter (2014). The Reconstruction Years. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse LLC. ISBN 9781491851920.

- Eicher, John H.; Eicher, David J. (2001). Civil War High Commands. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

- Garmon, Bonnie; Garmon, Jim (2009). Indian River Country 1880-1889. 1.

- Kirshner, Ralph (1999). The Class of 1861: Custer, Ames, and Their Classmates After West Point. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0-8093-2066-5.

- Lingley, Charles Ramsdell (1928). Allen Johnson, ed. Dictionary of American Biography Babcock, Orville E. 1. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 460.

- McFeely, William S. (1981). Grant: A Biography. Norton. ISBN 0-393-01372-3.

- McFeely, William S. (1974). Woodward, C. Vann, ed. Responses of the Presidents to Charges of Misconduct. New York, New York: Delacorte Press. pp. 133–162. ISBN 0-440-05923-2.

- Pletcher, David M. (1998). The Diplomacy of Trade and Investment: American Economic Expansion in the Hemisphere, 1865-1900. Columbia: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0-8262-1127-5.

- Knott, J. Proctor, Chairman (July 25, 1876). Testimony Before the U.S. House of Representatives Select Committee Considering the Whiskey Frauds. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

- Simon, John Y. (2002). "Ulysses S. Grant". In Graff, Henry. The Presidents: A Reference History (7th ed.). pp. 245–260. ISBN 0-684-80551-0.

- Smith, Jean Edward (2001). Grant. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-84927-5.

- White, Ronald C. (2016). American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S. Grant. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-5883-6992-5.

Primary

- "Orville Babcock Diaries". Mississippi State University Libraries. November 22, 2016.

Internet articles

- "MSU Libraries digitize Civil War diaries and letters". Mississippi State University. November 22, 2016.

- O'neil, Tim (February 25, 2017). "Feb. 25, 1876 • 'Whiskey ring' corruption trial in St. Louis was a national sensation". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Lee Enterprises © 2018. Retrieved September 25, 2018.

New York Times

- "A Cheap Democratic Trick" (PDF). New York Times. May 15, 1880.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Orville E. Babcock. |