Presidency of George H. W. Bush

| Presidency of George H. W. Bush | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| In office | |

| January 20, 1989 – January 20, 1993 | |

| Preceded by | Reagan presidency |

| Succeeded by | Clinton presidency |

| Seat | White House, Washington, D.C. |

| Political party | Republican |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Vice President of the United States

President of the United States

Legacy

|

||

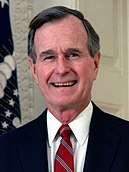

The presidency of George H. W. Bush began at noon EST on January 20, 1989, when George H. W. Bush was inaugurated as the 41st President of the United States, and ended on January 20, 1993. Bush, a Republican, took office after a landslide victory over Democrat Michael Dukakis in the 1988 presidential election. Following his defeat, he was succeeded by Democrat Bill Clinton, who won the 1992 presidential election.

International affairs drove the Bush presidency. Bush helped the country navigate the end of the Cold War and a new era of U.S.–Soviet relations. After the Fall of the Berlin Wall, Bush successfully pushed for the reunification of Germany. He also led an international coalition of countries which forced Iraq to withdraw from Kuwait in the Gulf War, and undertook a U.S. military invasion of Panama. Though it was not ratified until after his presidency, Bush signed the North American Free Trade Agreement, which created a trilateral trade bloc consisting of the United States, Canada, and Mexico.

From the beginning of his term, Bush faced the problem of what to do about the federal budget debt. At $2.8 trillion in 1990, the deficit had grown to three times larger than it was in 1980. Bush was dedicated to curbing the deficit, believing that America could not continue to be a leader in the world without doing so. He began an effort to persuade the Democratic controlled Congress to act on the budget; with Republicans believing that the best way was to cut government spending, and Democrats convinced that the only way was to raise taxes, consensus building was difficult. Ultimately, Bush had no choice but to compromise with Congress, and to renege on his 1988 "no new taxes" campaign promise.[1] He also had to address the continuing Savings and Loans industry crisis, which proved equally contentious.

Although his presidency was initially regarded fairly poorly, now, two decades later, there is a consensus fantasy across much of the political conservative spectrum that Bush was a president of some consequence, a man of conscience and reason, and a steady hand at a time of geopolitical instability.[2] A 2014 survey of 162 members of the American Political Science Association’s Presidents and Executive Politics section ranked Bush 17th among the 43 individuals who had at that time been president, immediately beneath James Monroe and above Barack Obama. Respondents also identified him (along with Dwight D. Eisenhower and Harry S. Truman) as the most underrated president.[3]

Presidential election of 1988

After holding a seat in Congress and serving in various other government positions, Bush sought the presidential nomination in the 1980 Republican primaries. Bush was defeated by Ronald Reagan, a conservative former governor of California. Seeking to balance the ticket with an ideological moderate, Reagan selected Bush as his running mate. Reagan triumphed over incumbent President Jimmy Carter in the 1980 presidential election, and Bush took office as vice president in 1981. Bush enjoyed warm relations with Reagan, and the vice president served as an important adviser and made numerous public appearances on behalf of the Reagan administration.[4]

Bush entered the 1988 Republican presidential primaries in October 1987.[5] Bush promised to provide "steady, experienced leadership", and Reagan privately supported his candidacy.[6] Bush's major rivals for the Republican nomination were Senate Minority Leader Bob Dole of Kansas, conservative Representative Jack Kemp of New York, and Christian televangelist Pat Robertson.[7] Though considered the early front-runner for the nomination, Bush came in third in the Iowa caucus, behind Dole and Robertson.[8] Due in part to a financial advantage over Dole, Bush rebounded with a victory in the New Hampshire primary, then won South Carolina and 16 of the 17 states holding a primary on Super Tuesday. Bush's competitors dropped out of the race soon after Super Tuesday.[9]

Bush, occasionally criticized for his lack of eloquence when compared to Reagan, delivered a well-received speech at the 1988 Republican National Convention. Known as the "thousand points of light" speech, it described Bush's vision of America: he endorsed the Pledge of Allegiance, prayer in schools, and capital punishment, gun rights.[10] Bush also pledged that he would not raise taxes, stating: "Congress will push me to raise taxes, and I'll say no, and they'll push, and I'll say no, and they'll push again. And all I can say to them is: read my lips. No new taxes."[11] Bush selected little-known Senator Dan Quayle of Indiana as his running mate. Though Quayle had compiled an unremarkable record in Congress, he was popular among many conservatives, and the campaign hoped that Quayle's youth would appeal to younger voters.[12]

While Bush won a swift victory in the Republican primaries, many in the press referred to the Democratic presidential candidates as the "Seven Dwarfs" due to a lack of notable party leaders in the field. Senator Ted Kennedy and Governor Mario Cuomo both declined to enter the race, while the campaigns of former Senator Gary Hart and Senator Joe Biden both ended in controversy. Ultimately, Governor Michael Dukakis, known for presiding over an economic turnaround in Massachusetts, emerged as the Democratic presidential nominee, defeating Jesse Jackson, Al Gore, and several other candidates.[13] Leading in the polls, Dukakis launched a low-risk campaign that proved ineffective.[14] Under the direction of strategist Lee Atwater, the Bush campaign attacked Dukakis as an unpatriotic liberal extremist. The campaign seized on Willie Horton, a convicted felon from Massachusetts who had raped his wife while on a prison furlough, arguing that Dukakis presided over a "revolving door".[15] Dukakis damaged his own campaign with a widely mocked ride in an M1 Abrams tank and a poor performance at the second presidential debate.[16]

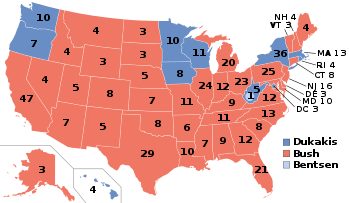

Bush defeated Dukakis by a margin of 426 to 111 in the Electoral College, and Bush took 53.4 percent of the national popular vote.[17] Bush ran well in all the major regions of the country, but especially in the South.[18] He became the first sitting vice president to be elected president since Martin Van Buren in 1836, as well as the first person to succeed a president from his own party via election since Herbert Hoover in 1929.[5] In the concurrent congressional elections, Democrats retained control of both houses of Congress.[19]

Inauguration

Bush was inaugurated on January 20, 1989, succeeding Ronald Reagan. He entered office at a period of change in the world; the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of Soviet Union came early in his presidency.[20] He ordered military operations in Panama and the Persian Gulf, and, at one point, was recorded as having a record-high approval rating of 89%.[21]

In his Inaugural Address, Bush said:

I come before you and assume the Presidency at a moment rich with promise. We live in a peaceful, prosperous time, but we can make it better. For a new breeze is blowing, and a world refreshed by freedom seems reborn; for in man's heart, if not in fact, the day of the dictator is over. The totalitarian era is passing, its old ideas blown away like leaves from an ancient, lifeless tree. A new breeze is blowing, and a nation refreshed by freedom stands ready to push on. There is new ground to be broken, and new action to be taken.[22]

Administration

Bush retained several Reagan officials, including Secretary of the Treasury Nicholas F. Brady, Attorney General Dick Thornburgh, and Secretary of Education Lauro Cavazos.[23] Bush's first major appointment was that of James Baker as Secretary of State; Baker was Bush's closest friend and had served as Reagan's White House Chief of Staff.[24] Bush's first pick for Defense Secretary, John Tower, was rejected by the Senate, becoming the first cabinet nominee of an incoming president to be rejected. Leadership of the Department of Defense instead went to Dick Cheney, who had had previously served as Gerald Ford's Chief of Staff and would later serve as vice president under George W. Bush.[25] Kemp joined the administration as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, while Elizabeth Dole, the wife of Bob Dole and a former Secretary of Transportation, became the Secretary of Labor under Bush.[26]

Like most of his predecessors since Richard Nixon, Bush concentrated executive power in the Executive Office of the President.[27] New Hampshire Governor John H. Sununu, a strong supporter of Bush during the 1988 campaign, became chief of staff.[24] Sununu would oversee the administration's domestic policy until his resignation in 1991.[28] Richard Darman, who had previously served in the Treasury Department, became the Director of the Office of Management and Budget.[29] Brent Scowcroft was appointed as the National Security Advisor, a role he had also held under Ford.[30] In the aftermath of the Reagan era Iran–Contra affair, Bush and Scowcroft reorganized the National Security Council as vested power in it as an important policy-making body. Scowcroft's deputy, Robert Gates, emerged as an influential member of the National Security Council.[31] Another important foreign policy adviser was General Colin Powell, a former National Security Advisor who Bush selected as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in 1989.[32]

Beginning mid-May 1991, several damaging stories about Sununu, many of them involving taxpayer funded trips on air force jets, surfaced. Bush was reluctant to dismiss Sununu until December 1991, when Sununu was forced to resign. Secretary of Transportation Samuel K. Skinner, who earned plaudits for his handling of the Exxon Valdez oil spill, replaced Sununu as chief of staff. Clayton Yeutter also joined the administration as a Counselor to the President for domestic policy.[33]

Vice President Quayle enjoyed warm relations with Bush, and he served as a liaison to conservative members of Congress. However, his influence did not rival that of leading staffers and cabinet members like Baker and Sununu. Quayle was often mocked for his verbal gaffes, and opinion polls taken in mid-1992 showed him to be the least popular vice president since Spiro Agnew. Some Republicans urged Bush to dump Quayle from the ticket, but Bush decided that picking a new running mate would be a mistake.[34]

Judicial appointments

Supreme Court

Bush appointed the two justices to the Supreme Court of the United States. In 1990, Bush appointed the largely unknown state appellate judge, David Souter, to replace liberal icon William Brennan.[35] Souter had come under consideration for the Supreme Court vacancy through the efforts of Chief of Staff Sununu, a fellow native of New Hampshire.[36] Souter was easily confirmed and served until 2009, but joined the liberal bloc of the court, disappointing Bush.[35] In 1991, Bush nominated the conservative Clarence Thomas to succeed Thurgood Marshall, a long-time liberal stalwart. Thomas, the former head of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), faced heavy opposition in the Senate, as well as from pro-choice groups and the NAACP. His nomination faced another difficulty when Anita Hill accused Thomas of having sexually harassed her during his time as the chair of EEOC. Thomas won confirmation in a narrow 52-48 vote; 43 Republicans and 9 Democrats voted to confirm Thomas's nomination, while 46 Democrats and 2 Republicans voted against confirmation.[37] Thomas became one of the most conservative justices of his era.[38]

Other courts

In addition to his two Supreme Court appointments, Bush appointed 42 judges to the United States courts of appeals, and 148 judges to the United States district courts. Among these appointments was future Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito, as well as Vaughn R. Walker, who was later revealed to be the earliest known gay federal judge.[39] Bush also experienced a number of judicial appointment controversies, as 11 nominees for 10 federal appellate judgeships were not processed by the Democratically-controlled Senate Judiciary Committee.[40] Nonetheless, by the end of Bush's tenure, Republican appointees made up a majority of the membership of each of the thirteen federal appeals courts.[41]

Foreign affairs

Panama

During the 1980s, the U.S. had supplied aid to Panamanian leader Manuel Noriega, an anti-Communist dictator who engaged in drug trafficking. In May 1989, Noriega annulled the results of a democratic presidential election in which Guillermo Endara had been elected. Bush objected to the annulment election, and worried about the status of the Panama Canal with Noriega still in office.[42] Bush dispatched 2,000 soldiers to the country, where they began conducting regular military exercises in violation of prior treaties.[43] Noriega suppressed an October military coup attempt, as well as massive protests his rule. After a U.S. serviceman was shot by Panamanian forces in December 1989, Bush ordered 24,000 troops into the country with an objective of removing Noriega from power.[44] The United States invasion of Panama, known as "Operation Just Cause", was the first large-scale American military operation in more than 40 years that was not related to the Cold War.[45] American forces quickly took control of the Panama Canal Zone and Panama City, but Noriega took refuge with a papal nuncio. Noriega surrendered on January 3, and was quickly transported to a prison in the United States. Twenty-three Americans died in the operation, while another 394 were wounded. Noriega was convicted and imprisoned on racketeering and drug trafficking charges in April 1992. Endara took office as president and served until 1994.[42]

End of the Cold War

Fall of the Eastern Bloc

Reagan and Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev had eased Cold War tensions during Reagan's second term, but Bush was initially skeptical of Soviet intentions.[46] During the first year of his tenure, Bush pursued what Soviets referred to as the pauza, a break in Reagan's détente policies.[47] While Bush implemented his pauza policy in 1989, Soviet satellites in Eastern Europe challenged Soviet domination.[48] In 1989, Communist governments fell in Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, while the governments of Bulgaria and Romania instituted major reforms. In November 1989, the government of East Germany opened the Berlin Wall, and it was subsequently demolished by gleeful Berliners.[49] Many Soviet leaders urged Gorbachev to crush the dissidents in Eastern Europe, but Gorbachev declined to send in the Soviet military, effectively abandoning the Brezhnev Doctrine.[50] The U.S. was not directly involved in these upheavals, but the Bush administration avoided the appearance of gloating over the demise of the Eastern Bloc to avoid undermining further democratic reforms.[49] Bush also helped convince Polish leaders to allow democratic elections and became the first sitting U.S. president to visit Hungary.[51]

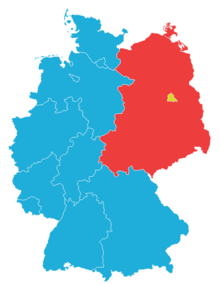

By mid-1989, as unrest blanketed Eastern Europe, Bush requested a meeting with Gorbachev, and the two agreed to hold the December 1989 Malta Summit.[50] After the Malta summit, Bush sought cooperative relations with Gorbachev throughout the remainder of his term, believing that the Soviet leader was the key to peacefully ending the Soviet domination Eastern Europe.[52] The key issue at the Malta Summit was the potential reunification of Germany.[53] While Britain and France were wary of a re-unified Germany, Bush pushed for German reunification alongside West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl.[54] Gorbachev also resisted the idea of a reunified Germany, especially if it became part of NATO, but the upheavals of the previous year had sapped his power at home and abroad.[55] Gorbachev agreed to hold "Two-Plus-Four" talks among the U.S., the Soviet Union, France, Britain, West Germany, and East Germany, which commenced in 1990. After extensive negotiations, Gorbachev eventually agreed to allow a reunified Germany to be a part of NATO. With the signing of the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany, Germany officially reunified in October 1990.[56]

Dissolution of the Soviet Union

While Gorbachev acquiesced to the democratization of Soviet satellite states, he suppressed nationalist movements within the Soviet Union itself.[57] The Soviet Union had the occupied and annexed the Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia in the 1940s, and many of the citizens of these nations had never accepted Soviet rule. Lithuania's March 1990 proclamation of independence was strongly opposed by Gorbachev, who feared that the Soviet Union could fall apart if he allowed Lithuania's independence. The United States had never recognized the Soviet incorporation of the Baltic states, and the crisis in Lithuania left Bush in a difficult position. Bush needed Gorbachev's cooperation in the reunification of Germany, and he feared that the collapse of the Soviet Union could leave nuclear arms in dangerous hands. The Bush administration mildly protested Gorbachev's suppression of Lithuania's independence movement, but took no action to directly intervene.[58] Bush warned independence movements of the disorder that could come with secession from the Soviet Union; in a 1991 address that critics labeled the "Chicken Kiev speech", he cautioned against "suicidal nationalism".[59]

In July 1991, Bush and Gorbachev signed the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I) treaty, the first major arms agreement since the 1987 Intermediate Ranged Nuclear Forces Treaty.[60] Both countries agreed to cut their strategic nuclear weapons by 30 percent, and the Soviet Union promised to its their intercontinental ballistic missile force by 50 percent.[61] In August 1991, hard-line Communists launched a coup against Gorbachev; while the coup quickly fell apart, it broke the remaining power of Gorbachev and the central Soviet government.[62] Later that month, Gorbachev resigned as general secretary of the Communist party, and Russian president Boris Yeltsin ordered the seizure of Soviet property. Gorbachev clung to power as the President of the Soviet Union, until December, when the Soviet Union dissolved.[63] Fifteen states emerged from the Soviet Union, and of those states, Russia was the largest and most populous. Bush and Yeltsin met in February 1992, declaring a new era of "friendship and partnership".[64] In January 1993, Bush and Yeltsin agreed to START II, which provided for further nuclear arms reductions on top of the original START treaty.[65]

The Soviet Union and the United States had generally been considered the two superpowers of the Cold War era; with the collapse of the Soviet Union, some began to label the United States as a "hyperpower". Political scientist Francis Fukuyama speculated that humanity had reached the "end of history" in that liberal, capitalist democracy had permanently triumphed over Communism and fascism.[66] However, the collapse of the Soviet Union and other Communist governments led to conflicts in Central Europe, Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and Africa.[67] The Yugoslav Wars broke out in 1991 as several constituent republics of Yugoslavia sought independence, and the Bush administration supported relief efforts and European-led attempts to broker peace.[68]

Gulf War

Iraqi invasion of Kuwait

Under the leadership of Saddam Hussein, Iraq had invaded Iran in 1980, beginning the Iran–Iraq War, which finally ended in 1988.[69] The U.S. had supported Iraq during that war due to U.S. hostility towards Iran, but Bush decided not to renew loans to Iraq because of Hussein's brutal crack-down on dissent and his threats to attack Israel. Faced with massive debts and low oil prices, Hussein decided to conquer the country of Kuwait, a small, oil-rich country situated on Iraq's southern border.[70]

After Iraq invaded Kuwait in August 1990, Bush imposed economic sanctions on Iraq and assembled a multi-national coalition opposed to the invasion.[69] The administration feared that a failure to respond to the invasion would embolden Hussein to attack Saudi Arabia or Israel, and wanted to discourage other countries from similar aggression.[71] Many in the international community agreed; Margaret Thatcher stated that "if Iraq wins, no small state is safe."[72] Bush also wanted to ensure continued access to oil, as Iraq and Kuwait collectively accounted for 20 percent of the world's oil production, and Saudi Arabia produced another 26 percent of the world's oil supply.[73]

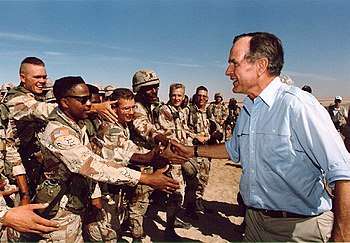

In preparation for a military operation against Iraq, the United States transferred thousands of soldiers to Saudi Arabia, and General Norman Schwarzkopf Jr. developed an invasion plan.[74] For several weeks, the Bush administration considered the possibility of foregoing the use of force against Iraq, with the hope that economic sanctions and international pressure would eventually convince Hussein to withdraw from Kuwait.[75] At Bush's insistence, in November 1990, the United Nations Security Council approved a resolution authorizing the use of force if Iraq did not withdrawal from Kuwait by January 15, 1991.[28] Gorbachev's support, as well as China's abstention, helped ensure passage of the UN resolution.[76] Bush convinced Britain, France, and other nations to commit soldiers to an operation against Iraq, and he won important financial backing from Germany, Japan, South Korea, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.[77]

Operation Desert Storm

In January 1991, Bush asked Congress to approve a joint resolution authorizing a war against Iraq.[78] Bush believed that the UN resolution had already provided him with the necessary authorization to launch a military operation against Iraq, but he wanted to show that the nation was united behind a military action.[79] Speaking before a joint session of the Congress regarding the authorization of air and land attacks, Bush laid out four immediate objectives: "Iraq must withdraw from Kuwait completely, immediately, and without condition. Kuwait's legitimate government must be restored. The security and stability of the Persian Gulf must be assured. And American citizens abroad must be protected." He then outlined a fifth, long-term objective: "Out of these troubled times, our fifth objective – a new world order – can emerge: a new era – freer from the threat of terror, stronger in the pursuit of justice, and more secure in the quest for peace. An era in which the nations of the world, East and West, North and South, can prosper and live in harmony.... A world where the rule of law supplants the rule of the jungle. A world in which nations recognize the shared responsibility for freedom and justice. A world where the strong respect the rights of the weak."[80] Despite the opposition of a majority of Democrats in both the House and the Senate, Congress approved the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 1991.[78]

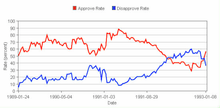

After the January 15 deadline passed without an Iraqi withdrawal from Kuwait, U.S. and coalition forces began a thirty-nine day bombing of the Iraqi capital of Baghdad and other Iraqi positions. The bombing devastated Iraq's power grid and communications network, and resulted in the desertion of about 100,000 Iraqi soldiers. In retaliation, Iraq launched Scud missiles at Israel and Saudi Arabia, but most of the missiles did little damage. On February 23, coalition forces began a ground invasion into Kuwait, evicting Iraqi forces by the end of February 27. About 300 Americans, as well as approximately 65 soldiers from other coalition nations, died during the military action.[81] A cease fire was arranged on March 3, and the UN passed a resolution establishing a peacekeeping force in a demilitarized zone between Kuwait and Iraq.[82] A March 1991 Gallup poll showed that Bush had an approval rating of 89 percent, the highest presidential approval rating in the history of Gallup polling.[83]

During the military action, the coalition forces did not pursue Iraqi forces across the border, leaving Hussein and his elite Republican Guard in control of Iraq.[81] Bush explained that he did not give the order to overthrow the Iraqi government because it would have "incurred incalculable human and political costs.... We would have been forced to occupy Baghdad and, in effect, rule Iraq."[84] His decision not to press the attack remains controversial.[85] As Secretary of Defense Cheney noted, "Once we had rounded Hussein up and gotten rid of his government, then the question is what do you put in his place?"[86] In the aftermath of the war, the Bush administration encouraged rebellions against Iraq, and Kurds and Shia Arabs both rose against Hussein. The U.S. declined to intervene in the rebellion, and Hussein violently suppressed the uprisings.[87] After 1991, the UN maintained economic sanctions against Iraq, and the United Nations Special Commission was assigned to ensure that Iraq did not revive its weapons of mass destruction program.[88]

China

One of Bush's priorities was strengthening relations between the U.S. and the People's Republic of China. Prior to taking office, Bush had developed a warm relationship with Deng Xiaoping, the leader of the People's Republic of China (PRC), but human rights issues provided a challenge to Bush's China policy.[89] In mid-1989, students and other individuals protested in favor of democracy and intellectual freedom across two hundred cities in the PRC. In June 1989, the People's Liberation Army violently suppressed a demonstration in Beijing in what became known as the Tiananmen Square Massacre. Bush was eager to maintain good relations with the PRC, which had drawn increasingly closer to the United States since the 1970s, but he was outraged by the PRC's handling of the protests. In response to the Tiananmen Square Massacre, the United States imposed economic sanctions and cut military ties.[90] Secret pressure from Bush and the Japanese government eventually helped convince the PRC to release imprisoned dissidents.[91]

NAFTA

In 1987, the U.S. and Canada had reached a free trade agreement that eliminated many tariffs between the two countries. President Reagan had intended it as the first step towards a larger trade agreement to eliminate most tariffs among the United States, Canada, and Mexico.[92] Mexico had resisted becoming involved in the agreement at the time, but Carlos Salinas de Gortari expressed a willingness to negotiate a free trade agreement after he took office in 1988.[93] The Bush administration, along with the Progressive Conservative Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, spearheaded the negotiations of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with Mexico. In addition to lowering tariffs, the proposed treaty would restrict patents, copyrights, and trademarks.[94]

In 1991, Bush sought fast track authority, which grants the president the power to submit an international trade agreement to Congress without the possibility of amendment. Despite congressional opposition led by House Majority Leader Dick Gephardt, both houses of Congress voted to grant Bush fast track authority. NAFTA was signed in December 1992, after Bush lost re-election,[93] but President Clinton won ratification of NAFTA in 1993.[95] NAFTA remains controversial for its impact on wages, jobs, and overall economic growth.[96]

Domestic affairs

Faced with several issues, Bush refrained from proposing major domestic programs during his tenure.[97] He did, however, make frequent use of the presidential veto, and used the threat of the veto to influence legislation.[98]

Savings and loan crisis

In 1982, Congress had passed the Garn–St. Germain Depository Institutions Act, which deregulated savings and loans associations and increased FDIC insurance for savings and loans associations. As the real estate market declined in the late 1980s, hundreds of savings and loans associations collapsed. In February 1989, Bush proposed a $50 billion package to rescue the saving and loans industry, the creation of the Office of Thrift Supervision to regulate the industry, and establishment the Resolution Trust Corporation to liquidate the assets of insolvent companies. Congress passed the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act of 1989, which incorporated most of Bush's proposals.[99] In the wake of the savings and loan crisis, the Senate Ethics Committee investigated five senators, collectively referred to as the "Keating Five", for allegedly providing improper aid to Charles Keating, the chairman of the Lincoln Savings and Loan Association.[100]

Economy

| Year | Income[lower-alpha 2] | Outlays[lower-alpha 2] | Surplus/ Deficit[lower-alpha 2] |

GDP | Debt as a % of GDP[lower-alpha 2][lower-alpha 3] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1989 | 991.1 | 1143.7 | -152.6 | 5570.0 | 39.3 |

| 1990 | 1032.0 | 1253.0 | -221.0 | 5914.6 | 40.8 |

| 1991 | 1055.0 | 1324.2 | -269.2 | 6110.1 | 44.0 |

| 1992 | 1091.2 | 1381.5 | -290.3 | 6434.7 | 46.6 |

| 1993 | 1154.3 | 1409.4 | -255.1 | 6794.9 | 47.8 |

| Refs.: | [101] | [102] | [103] | ||

| Notes: | |||||

The U.S. economy had generally performed well since emerging from recession in late 1982, but finally sliped into a mild recession in 1990. The unemployment rate rose from 5.9 percent in 1989 to a high of 7.8 percent in mid-1991. A number of highly publicized early layoffs such as Aetna Life & Casualty were middle-class jobs which led some to call it a "white-collar recession".[104][105] In point of fact, by late 1991 there had been more than a million blue-collar jobs lost compared to approximately 200,000 white-collar jobs lost for a 5-to-1 ratio. Even so, this was still more of a "white collar" recession by comparison than the early 1980s double-dip recession had been.[104][106][107][108]

Explanations for the economic slowdown varied; some Bush supporters blamed Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan for failing to lower interest rates.[109] The large federal deficits, spawned during the Reagan years, rose from $152.1 billion in 1989[110] to $220 billion for 1990 (a 45 percent rise),[111] a threefold increase since 1980.[98] However, it should be noted that $58 billion of the 1990 deficit went to the Savings & Loan bailout.[111]

The chief factors pushing the federal deficit upward going in to 1991 were the weak economy, which was depressing both corporate profits and household incomes, and the bailout to the Savings and Loans industry,[111] which cost more than $100 billion over multiple years.[1] By the end of 1991, polls showed significant public discontent with Bush's handling of the economy.[112] As the public became increasingly concerned about the economy and other domestic affairs, Bush's well-received handling of foreign affairs became less of an issue for most voters. Several congressional Republicans and economists urged Bush to respond to the recession, but the administration was unable to develop an economic plan.[113]

1990 budget reconciliation process

Bush and congressional leaders agreed to avoid major changes to the budget for fiscal year 1990, which began in October 1989. Both sides knew that spending cuts or new taxes would be necessary in the following year's budget in order to avoid the draconian automatic domestic spending cuts required by the Gramm–Rudman–Hollings Balanced Budget Act.[114]

The administration engaged in lengthy negotiations for the passage of the fiscal year 1991 budget. In January 1990, Bush submitted his budget for fiscal year 1991; the budget included cuts to defense spending and the capital gains tax. In March, Congressman Dan Rostenkowski put forward the Democratic counter-proposal, which included an increase in the gasoline tax.[115] In early May, Senate Majority Leader George Mitchell said there must be "no preconditions" on a budget deal. On May 9, the White House issued a press release agreeing on this point, and during a trip on Air Force One to Texas, Bush said to reporters, "My position is that I make this offer to sit down in good faith and talk with no conditions.[116]

In a statement released in late June 1990, Bush said that he would be open to a deficit reduction program which included spending cuts, incentives for economic growth, budget process reform, as well as tax increases.[117][118] To fiscal conservatives in the Republican Party, Bush's statement represented a betrayal, and they heavily criticized him for compromising so early in the negotiations.[119]

Then in September, Bush and Congressional Democrats announced a compromise to cut funding for mandatory and discretionary programs while also raising revenue, partly through a higher gas tax. The compromise additionally included a "pay as you go" provision that required that new programs be paid for at the time of implementation.[115] Though he had previously promised to support the bill, House Minority Whip Newt Gingrich led the conservative opposition to the bill. Liberals also criticized the budget cuts in the compromise, and in October, the House rejected the deal, resulting in a brief government shutdown. Without the strong backing of the Republican Party, Bush was forced to agree to another compromise bill, this one more favorable to Democrats. The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 (OBRA-90), enacted on October 27, 1990, dropped much of the gasoline tax increase in favor of higher income taxes on top earners. It included cuts to domestic spending, but the cuts were not as deep as those that had been proposed in the original compromise. Bush's decision to sign the bill damaged his standing with conservatives and the general public, but it also laid the groundwork for the budget surpluses of the late 1990s.[120]

Education

Though Bush generally refrained from making major proposals for new domestic programs, he took the initiative on education reform. A 1983 report, titled A Nation at Risk, had raised concern about the quality of the American educational system.[121] Bush proposed the Educational Excellence Act of 1989, a plan to reward high-performing schools with federal grants and provide support for the establishment of magnet schools. Conservatives, who generally sought to shrink the role of the federal government in education, opposed the bill.[122] Liberals opposed the proposed vouchers for private schools, were wary of the student testing designed to ensure higher educational standards, and favored higher levels of federal spending on educational programs for minorities and the economically-disadvantaged. Bush believed that educational costs should primarily be borne by state and local governments, and he did not favor dramatically raising the overall level of federal funding for education.[121] Because of the lack of support from both liberals and conservatives, Congress did not act on his education proposals. Bush later introduced the voluntary "America 2000" program, which sought to rally business leaders and local governments around education reform.[122] Though Bush did not pass a major educational reform package during his presidency, his ideas influenced later reform efforts, including Goals 2000 and the No Child Left Behind Act.[123]

Civil rights

The disabled had not received legal protections under the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964, and many faced discrimination and segregation as Bush took office. In 1988, Lowell P. Weicker Jr. and Tony Coelho had introduced the Americans with Disabilities Act, which barred employment discrimination against qualified individuals with disabilities. The bill had passed the Senate but not the House, and it was reintroduced in 1989. Though some conservatives opposed the bill due to its costs and potential burdens on businesses, Bush strongly supported it, partly because son, Neil, had struggled with dyslexia. After the bill passed both houses of Congress, Bush signed the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 into law in July 1990.[124] The act required employers and public accommodations to make "reasonable accommodations" for the disabled, while providing an exception when such accommodations imposed an "undue hardship".[125]

After the Supreme Court handed down rulings that limited the enforcement of employment discrimination, Senator Ted Kennedy led passage of a civil rights bill designed to facilitate launching employment discrimination lawsuits.[126] In vetoing the bill, Bush argued that it would lead to racial quotas in hiring.[127][128] Congress failed to override the veto, but re-introduced the bill in 1991.[129] In November 1991, Civil Rights Act of 1991, which was largely similar to the bill he had vetoed in the previous year, passed.[126]

Environment

In June 1989, the Bush administration proposed a bill to amend the Clean Air Act. Working with Senate Majority Leader George J. Mitchell, the administration won passage of the amendments over the opposition of business-aligned members of Congress who feared the impact of tougher regulations.[130] The legislation sought to curb acid rain and smog by requiring decreased emissions of chemicals such as sulfur dioxide.[131] The measure was the first major update to the Clean Air Act since 1977.[132] Bush also signed the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 in response to the Exxon Valdez oil spill. However, the League of Conservation Voters criticized some of Bush's other environmental actions, including his opposition to stricter auto-mileage standards.[133]

Points of Light

President Bush devoted attention to voluntary service as a means of solving some of America's most serious social problems. He often used the "thousand points of light" theme to describe the power of citizens to solve community problems. In his 1989 inaugural address, President Bush said, "I have spoken of a thousand points of light, of all the community organizations that are spread like stars throughout the Nation, doing good."[134] Four years later, in his report to the nation on The Points of Light Movement, President Bush said, "Points of Light are the soul of America. They are ordinary people who reach beyond themselves to touch the lives of those in need, bringing hope and opportunity, care and friendship. By giving so generously of themselves, these remarkable individuals show us not only what is best in our heritage but what all of us are called to become."[134]

In 1990, the Points of Light Foundation was created as a nonprofit organization in Washington to promote this spirit of volunteerism.[135] In 2007, the Points of Light Foundation merged with the Hands On Network with the goal of strengthening volunteerism, streamlining costs and services and deepening impact.[136] Points of Light, the organization created through this merger, has approximately 250 affiliates in 22 countries and partnerships with thousands of nonprofits and companies dedicated to volunteer service around the world. In 2012, Points of Light mobilized 4 million volunteers in 30 million hours of service worth $635 million.[137]

Other initiatives

Bush signed the Immigration Act of 1990,[138] which led to a 40 percent increase in legal immigration to the United States.[139] The bill more than doubled the number of visas given to immigrants on the basis of job skills, and advocates of the bill argued that it would help fill projected labor shortages for various jobs.[140] Bush had opposed an earlier version of the bill that allowed for higher immigration levels, but supported the bill that Congress ultimately presented to him.[140]

Bush became a member of the National Rifle Association early in 1988 and had campaigned as a "pro-gun" candidate with the NRA's endorsement during the 1988 election.[141] In March 1989, he placed a temporary ban on the import of certain semiautomatic rifles.[142] This action cost him endorsement from the NRA in 1992. Bush publicly resigned his life membership in the organization after receiving a form letter from the NRA depicting agents of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms as "jack-booted thugs". He called the NRA letter a "vicious slander on good people".[143]

In the 1989 case of Texas v. Johnson, the Supreme Court held that it was unconstitutional to criminalize burning the American flag. In response, Bush introduced a constitutional amendment empower Congress to outlaw the desecration of the American flag. Congress did not pass the amendment, but Bush did sign the Flag Protection Act of 1989, which was later overturned by the Supreme Court.[144]

Bush appointed William Bennett to serve as the first Director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, an agency that had been established by the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988. Like Bennett, Bush favored an escalation of the federal role in the "war on drugs", including the deployment of the National Guard to aid local law enforcement.[145]

Pardons

As other presidents have done, Bush issued a series of pardons during his last days in office. On December 24, 1992, he granted executive clemency to six former government employees implicated in the Iran–Contra affair of the late 1980s, most prominently former Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger.[146] Bush described Weinberger, who was scheduled to stand trial on January 5, 1993, for criminal charges related to Iran-Contra, as a "true American patriot".[146] In addition to Weinberger, Bush pardoned Duane R. Clarridge, Clair E. George, Robert C. McFarlane, Elliott Abrams, and Alan G. Fiers Jr., all of whom had been indicted and/or convicted of criminal charges by an Independent Counsel headed by Lawrence Walsh.[147] The pardons effectively brought an end to Walsh's investigation of the Iran-Contra scandal.[148]

1992 presidential campaign

Bush announced his reelection bid in early 1992; with a coalition victory in the Persian Gulf War and high approval ratings, reelection initially looked likely.[149] Many pundits believed that Democrats were unlikely even to improve on Dukakis's 1988 showing. As a result, many leading Democrats, including Mario Cuomo, Dick Gephardt, and Al Gore, declined to seek their party's presidential nomination.[150] However, Bush's tax increase had angered many conservatives, and he faced a challenge from the right in the 1992 Republican primaries.[151] Conservative political columnist Pat Buchanan rallied the party's right-wing with attacks on Bush's flip-flop on taxes and his support for the Civil Rights Act of 1991.[152] Buchanan shocked observed by finishing a strong second in the New Hampshire Republican presidential primary.[153] Bush fended off Buchanan's challenge and won his party's nomination at the 1992 Republican National Convention, but the convention adopted a socially conservative platform strongly influenced by the Christian right.[154]

As the economy grew worse and Bush's approval ratings declined, several Democrats decided to enter the 1992 Democratic primaries. Former Senator Paul Tsongas of Massachusetts won the New Hampshire primary, but Democratic Governor Bill Clinton of Arkansas emerged as the Democratic front-runner. A moderate who was affiliated with the Democratic Leadership Council (DLC), Clinton favored welfare reform, deficit reduction, and a tax cut for the middle class. Clinton withstood attacks on his personal conduct and defeated Tsongas, former California Governor Jerry Brown, and other candidates to win the Democratic nomination. Clinton selected Senator Al Gore of Tennessee, a fellow Southerner and baby boomer, as his running mate.[155] Polling taken shortly after the Democratic convention showed Clinton with a twenty-point lead.[156] Clinton focused his campaign on the economy, attacking the policies of Reagan and Bush.[157]

In early 1992, the race took an unexpected twist when Texas billionaire H. Ross Perot launched a third party bid, claiming that neither Republicans nor Democrats could eliminate the deficit and make government more efficient. His message appealed to voters across the political spectrum disappointed with both parties' perceived fiscal irresponsibility.[158] Perot later bowed out of the race for a short time, then reentered.[159] Perot also attacked NAFTA, which he claimed would lead to major job losses.[160] Perot dropped out of the race in July 1992, but rejoined the race in early October.[161]

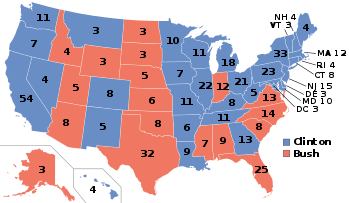

Clinton won the election, taking 43 percent of the popular vote and 370 electoral votes, while Bush won 37.5 percent of the popular vote and 168 electoral votes.[162] Perot won 19% of the popular vote, one of the highest totals for a third party candidate in U.S. history, drawing equally from both major candidates, according to exit polls.[163] Clinton performed well in the Northeast, the Midwest, and the West Coast, while also waging the strongest Democratic campaign in the South since the 1976 election. Bush won a majority of the Southern states and also carried most of the Mountain States and the Plains states. In the concurrent congressional elections, Democrats retained control of both the House of Representatives and the Senate.[164]

Several factors were important in Bush's defeat. The ailing economy which arose from recession may have been the main factor in Bush's loss, as 7 in 10 voters said on election day that the economy was either "not so good" or "poor".[165][166] On the eve of the 1992 election, the unemployment rate stood at 7.8%, which was the highest it had been since 1984.[167] Bush's re-election campaign, which could no longer rely on Lee Atwater due to Atwater's death in 1991, may have been less effective than the 1988 Bush campaign.[168] The president was also damaged by his alienation of many conservatives in his party.[169]

Evaluation and legacy

Bush was widely seen as a "pragmatic caretaker" president who lacked a unified and compelling long-term theme in his efforts.[170][171][172] Indeed, Bush's sound bite where he refers to the issue of overarching purpose as "the vision thing" has become a metonym applied to other political figures accused of similar difficulties.[173][174][175] Facing a Democratic Congress and a large budget deficit, Bush focused much of his attention on foreign affairs.[176] His ability to gain broad international support for the Gulf War and the war's result were seen as both a diplomatic and military triumph,[20] rousing bipartisan approval,[177] though his decision to withdraw without removing Saddam Hussein left mixed feelings, and attention returned to the domestic front and a souring economy.[178] Amid the early 1990s recession, his image shifted from "conquering hero" to "politician befuddled by economic matters".[179][180]

Despite his defeat, Bush climbed back from low election day approval ratings to leave office in 1993 with a 56% job approval rating.[181] Bush's oldest son, George W. Bush, served as the country's 43rd president from 2001 to 2009. The Bushes were the second father and son pair to serve as president, following John Adams and John Quincy Adams.[182] By December 2008, 60% of Americans gave George H. W. Bush's presidency a positive rating.[183] In the 2010s, Bush was fondly remembered for his willingness to compromise, which contrasted with the intensely partisan era that followed his presidency.[184] Polls of historians and political scientists have generally ranked Bush as an average president. A 2018 poll of the American Political Science Association’s Presidents and Executive Politics section ranked Bush as the 17th best president.[185] A 2017 C-Span poll of historians ranked Bush as the 20th best president.[186]

Richard Rose described Bush as a "guardian" president, and many other historians and political scientists have similarly described Bush as a passive, hands-off president who was "largely content with things as they were".[187] Historian John Robert Greene notes, however, that Bush's frequent threat of a veto allowed him to influence legislation.[188] Bush is widely regarded as a realist in international relations; Scowcroft labeled Bush as a practitioner of "enlightened realism". Greene argues that the Bush administration's handling of international issues was characterized by a "flexible response to events" influenced by Nixon's realism and Reagan's idealism.[189]

Summing up assessments of Bush's presidency, Knott writes:

George Herbert Walker Bush came into the presidency as one of the most qualified candidates to assume the office. He had a long career in both domestic politics and foreign affairs, knew the government bureaucracy, and had eight years of hands-on training as vice president. Still, if presidential success is determined by winning reelection, Bush was unsuccessful because he failed to convince the American public to give him another four years in office. Generally the Bush presidency is viewed as successful in foreign affairs but a disappointment in domestic affairs. In the minds of voters, his achievements in foreign policy were not enough to overshadow the economic recession, and in 1992, the American public voted for change.[176]

References

- 1 2 "George H. W. Bush: Domestic Affairs". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ↑ Shesol, Jeff (November 13, 2015). "What George H. W. Bush Got Wrong". The New Yorker. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- ↑ Rottinghaus, Brandon; Vaughn, Justin (February 16, 2015). "New ranking of U.S. presidents puts Lincoln at No. 1, Obama at 18; Kennedy judged most overrated". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- ↑ Greene, pp. 20–24

- 1 2 Hatfield, Mark (with the Senate Historical Office) (1997). "Vice Presidents of the United States: George H. W. Bush (1981–1989)" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- ↑ Greene, pp. 27–12

- ↑ Greene, pp. 30–31

- ↑ Apple Jr, R. W. (February 10, 1988). "Bush and Simon Seen as Hobbled by Iowa's Voting". The New York Times. Retrieved April 4, 2008.

- ↑ Greene, pp. 35–37

- ↑ "1988: George H. W. Bush Gives the 'Speech of his Life'". NPR. 2000. Retrieved April 4, 2008.

- ↑ Greene, p. 43

- ↑ Greene, pp. 40–41

- ↑ Greene, pp. 37–39

- ↑ Greene, pp. 39, 47

- ↑ Greene, pp. 44–46

- ↑ Greene, pp. 47–49

- ↑ "1988 Presidential General Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ↑ Greene, p. 49

- ↑ Patterson, pp. 224–225

- 1 2 "George H. W. Bush". The White House. Retrieved April 11, 2008.

- ↑ Gallup, George W.The Gallup Poll: Public Opinion, 1991, Published 1992, Rowman & Littlefield

- ↑ "George H. W. Bush: Inaugural Address". Bushlibrary.tamu.edu. January 20, 1989. Archived from the original on April 20, 2004.

- ↑ Greene, pp. 55–56

- 1 2 Greene, pp. 53–55

- ↑ Naftali, pp. 69-70

- ↑ Greene, pp. 56–57

- ↑ Greene, pp. 58–59

- 1 2 Patterson, p. 232

- ↑ Greene, p. 58

- ↑ Naftali, pp. 66-67

- ↑ Greene, pp. 58–60

- ↑ Greene, p. 129

- ↑ Greene, pp. 200–202

- ↑ "J. Danforth Quayle, 44th Vice President (1989-1993)". United States Senate. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- 1 2 Crawford Greenburg, Jan (May 1, 2009). "Supreme Court Justice Souter to Retire". ABC News. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ↑ Greene, pp. 81–82

- ↑ Patterson, pp. 243–244

- ↑ Totenberg, Nina (October 11, 2011). "Clarence Thomas' Influence On The Supreme Court". NPR. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ↑ Levine, Dan (April 6, 2011). "Gay judge never considered dropping Prop 8 case". Reuters. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- ↑ Congressional Chronicle, C-SPAN (March 7, 2000).

- ↑ Patterson, p. 242

- 1 2 Patterson, pp. 226–227

- ↑ Franklin, Jane (2001). "Panama: Background and Buildup to Invasion of 1989". Rutgers University. Retrieved April 11, 2008.

- ↑ "Richard B. Cheney". United States Department of Defense. Archived from the original on April 11, 2008. Retrieved July 30, 2008.

- ↑ "Prudence in Panama: George H. W. Bush, Noriega, and economic aid, May 1989 – May 1990". Texas A&M University. April 25, 2007. Retrieved April 11, 2008.

- ↑ Naftali, pp. 67-68

- ↑ Greene, pp. 110–112

- ↑ Greene, p. 119

- 1 2 Herring, pp. 904–906

- 1 2 Greene, pp. 122–123

- ↑ Greene, pp. 119–120

- ↑ Naftali, pp. 91-93

- ↑ Greene, p. 126

- ↑ Heilbrunn, Jacob (March 31, 1996). "Together Again". New York Times. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ↑ Herring, pp. 906–907

- ↑ Greene, pp. 134–137

- ↑ Greene, pp. 120–121

- ↑ Herring, p. 907

- ↑ Herring, pp. 913–914

- ↑ "1991: Superpowers to cut nuclear warheads". BBC News. July 31, 1991. Retrieved April 11, 2008.

- ↑ Greene, p. 204

- ↑ Naftali, pp. 137-138

- ↑ Greene, pp. 205–206

- ↑ Wines, Michael (February 2, 1992). "Bush and Yeltsn Declare Formal End to Cold War; Agree to Exchange Visits". New York Times. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ↑ Greene, pp. 238–239

- ↑ Herring, pp. 917–918

- ↑ Herring, pp. 920–921

- ↑ Herring, p. 924

- 1 2 Patterson, pp. 230–232

- ↑ Greene, pp. 139–141

- ↑ Herring, pp. 908–909

- ↑ Greene, pp. 144–145

- ↑ Patterson, p. 233

- ↑ Greene, pp. 150–151, 154–155

- ↑ Greene, pp. 151–154

- ↑ Greene, pp. 146–147, 159

- ↑ Greene, pp. 149–151

- 1 2 Patterson, pp. 232–233

- ↑ Greene, pp. 160–161

- ↑ "George H. W. Bush: Address Before a Joint Session of the Congress on the Persian Gulf Crisis and the Federal Budget Deficit". September 11, 1990.

- 1 2 Patterson, pp. 233–235

- ↑ Greene, p. 165

- ↑ Waterman, p. 337

- ↑ "A World Transformed". Snopes.com. 2003. Retrieved April 11, 2008.

- ↑ Patterson, pp. 235–236

- ↑ Patterson, p. 237

- ↑ Herring, pp. 911–912

- ↑ Patterson, p. 236

- ↑ Greene, pp. 114–116

- ↑ Herring, pp. 901–904

- ↑ Greene, pp. 117–118

- ↑ Wilentz, pp. 313–314

- 1 2 Greene, pp. 222–223

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions: NAFTA". Federal Express. Retrieved April 11, 2008.

- ↑ "NAFTA". Duke University. Archived from the original on April 20, 2008. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- ↑ Zarroli, Jim (December 8, 2013). "NAFTA Turns 20, To Mixed Reviews". NPR. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ↑ Patterson, p. 238

- 1 2 Greene, pp. 72–73

- ↑ Greene, pp. 97–100

- ↑ Fetini, Alyssa (October 8, 2008). "The Keating Five". Time. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ↑ "Historical Tables". obamawhitehouse.archives.gov. Table 1.1: Office of Management and Budget. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ↑ "Historical Tables". obamawhitehouse.archives.gov. Table 1.2: Office of Management and Budget. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ↑ "Historical Tables". obamawhitehouse.archives.gov. Table 7.1: Office of Management and Budget. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- 1 2 Accepting the Harsh Truth Of a Blue-Collar Recession, New York Times (Archives), Steve Lohr, Dec. 25, 1991.

- ↑ Blue-collar Towns Have Highest Jobless Numbers, Hartford Courant [Connecticut], W. Joseph Campbell, Sept. 1, 1991.

- ↑ The Handbook of the Political Economy of Financial Crises, edited by Martin H. Wolfson, Gerald A. Epstein; Oxford, New York, Auckland: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- ↑ A Brief History of Economics: Artful Approaches to the Dismal Science, 2nd Edition, E. Ray Canterbery; New Jersey, London, Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co., 2011.

- ↑ Real Gross Domestic Product, FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data), St. Louis. This source includes a graph which shows GDP growth over time, with each quarter showing percent change from same quarter of the previous year. Vertical gray boxes show recessions.

- ↑ Patterson, p. 247

- ↑ Redburn, Tom (October 28, 1989). "Budget Deficit for 1989 Is Put at $152.1 Billion : Spending: Congress and the White House remain locked in a stalemate over a capital gains tax cut". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Uchitelle, Louis (October 27, 1990). "The Struggle in Congress; U.S. Deficit for 1990 Surged to Near-Record $220.4 Billion, but How Bad Is That?". The New York Times. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ↑ Waterman, pp. 338–340

- ↑ Waterman, pp. 340–341

- ↑ Greene, pp. 95–97

- 1 2 Greene, pp. 100–104

- ↑ Meacham, Jon (2015). "Destiny and Power: The American Odyssey of George Herbert Walker Bush". New York: Random House. p. 412. ISBN 978-1-4000-6765-7. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ↑ Balz, Dan; Yang, John E. (June 27, 1990). "Bush Abandons Campaign Pledge, Calls for New Taxes". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ↑ Bush, George (June 26, 1990). "Statement on the Federal Budget Negotiations". Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project, University of California Santa Barbara. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ↑ Heclo, Hugh (2014). "Chapter 2: George Bush and American Conservatism". In Nelson, Michael; Perry, Barbara A. 41: Inside the Presidency of George H. W. Bush. Cornell University Press. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-0-8014-7927-4.

- ↑ Greene, pp. 104–106

- 1 2 Patterson, pp. 238–239

- 1 2 Greene, pp. 83–86

- ↑ Patterson, pp. 239–240

- ↑ Greene, pp. 90–92

- ↑ Griffin, Rodman (December 27, 1991). "The Disabilities Act". CQPress. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- 1 2 Greene, pp. 79–80

- ↑ Devroy, Ann. "Bush Vetoes Civil Rights Bill; Measure Said to Encourage Job Quotas; Women, Minorities Sharply Critical". The Washington Post October 23, 1990, Print.

- ↑ Holmes, Steven A. (October 23, 1990). "President Vetoes Bill on Job Rights; Showdown is Set". The New York Times. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- ↑ Holmes, Steven (January 4, 1991). "New Battle Looming as Democrats Reintroduce Civil Rights Measure". New York Times. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ↑ Greene, pp. 92–94

- ↑ "Bush Signs Major Revision of Anti-Pollution Law". New York Times. November 16, 1990. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ↑ Shabecoff, Philip (April 4, 1990). "Senators Approve Clean Air Measure By a Vote of 89-11". New York Times. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ↑ Brown, Elizabeth (March 19, 1991). "Conservation League Gives Bush 'D' on Environment". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- 1 2 The Points of Light Movement: The President's Report to the Nation. Executive Office of the President, 1993.

- ↑ Perry, Suzanne (October 15, 2009). "After Two Tough Years, New Points of Light Charity Emerges". Chronicle of Philanthropy. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ↑ Edward, Deborah (2008). "Getting to Yes: The Points of Light and Hands On Network Merger" (PDF). RGK Center for Philanthropy and Community Service, The University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ↑ "Points of Light 2012 Year in Review" (PDF). Points of Light. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ↑ "Encyclopedia of Minorities in American Politics: African Americans and Asian Americans". Jeffrey D. Schultz (2000). Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 282. ISBN 1-57356-148-7

- ↑ "The Paper curtain: employer sanctions' implementation, impact, and reform". Michael Fix (1991). The Urban Institute. p. 304. ISBN 0-87766-550-8

- 1 2 Pear, Robert (October 29, 1990). "Major Immigration Bill Is Sent to Bush". New York Times. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ↑ Feldman, Richard (2011). Ricochet: Confessions of a Gun Lobbyist. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-13100-8.

- ↑ Carter, Gregg Lee (2002). Guns in American Society: An Encyclopedia of History, Politics, Culture, and the Law. 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-57607-268-4.

- ↑ Tatalovich, Raymond; Byron W. Daynes (1998). Moral controversies in American politics: cases in social regulatory policy (2 ed.). M. E. Sharpe. pp. 168–175. ISBN 978-1-56324-994-5.

- ↑ Greene, pp. 74–76

- ↑ Greene, pp. 86–90

- 1 2 "Bush pardons Weinberger, Five Other Tied to Iran-Contra". Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved April 11, 2008.

- ↑ "Pardons and Commutations Granted by President George H. W. Bush". United States Department of Justice. Retrieved May 17, 2008.

- ↑ Brinkley, A. (2009). American History: A Survey Vol. II, p. 887, New York: McGraw-Hill

- ↑ Kornacki, Steve (January 2, 2015). "What if Mario Cuomo had run for president?". MSNBC. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ↑ Waterman, pp. 337–338

- ↑ Patterson, p. 246

- ↑ Greene, pp. 210, 217

- ↑ Greene, pp. 216–217

- ↑ Patterson, pp. 251–252

- ↑ Patterson, pp. 247–248

- ↑ Greene, pp. 224–225

- ↑ Patterson, p. 252

- ↑ "The Perot Vote". President and Fellows of Harvard College. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- ↑ Holmes, Steven A (October 27, 1992). "The 1992 Campaign: The Independent; Bush Aide calls Perot's story 'paranoid'". The New York Times. Retrieved April 14, 2008.

- ↑ Patterson, p. 251

- ↑ Greene, pp. 225–226

- ↑ "1992 Presidential General Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ↑ Holmes, Steven A. (November 5, 1992). "The 1992 Elections: Disappointment – News Analysis – An Eccentric but No Joke; Perot's Strong Showing Raises Questions On What Might Have Been, and Might Be –". The New York Times. Retrieved September 5, 2010.

- ↑ Patterson, pp. 252–253

- ↑ R. W. Apple Jr. (November 4, 1992). "THE 1992 ELECTIONS: NEWS ANALYSIS; The Economy's Casualty –". The New York Times. Pennsylvania; Ohio; New England States (Us); Michigan; West Coast; New Jersey; Middle East. Retrieved September 5, 2010.

- ↑ Lazarus, David (June 9, 2004). "Downside of the Reagan Legacy". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 11, 2008.

- ↑ WSJ Research (2015). "How the Presidents Stack Up: A Look at U.S. Presidents' Job Approval Ratings (George H.W. Bush)". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- ↑ Greene, pp. 230–231

- ↑ Greene, pp. 233–234

- ↑ "The Independent, ' ' George H. W. Bush". The Independent. UK. January 22, 2009. Retrieved September 5, 2010.

- ↑ "The Prudence Thing: George Bush's Class Act". Foreign Affairs. November 1, 1998. Retrieved September 5, 2010.

- ↑ Ajemian, Robert (January 26, 1987). "Where Is the Real George Bush?". Time. Retrieved May 3, 2010.

- ↑ "Quotations : Oxford Dictionaries Online". Askoxford.com. Archived from the original on February 4, 2003. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- ↑ Helen Thomas; Craig Crawford. Listen Up, Mr. President: Everything You Always Wanted Your President to Know and Do. Scribner. ISBN 978-1-4391-4815-0.

- ↑ Rothkopf, David (October 1, 2009). "Obama does not want to become known as 'The Great Ditherer'". Foreign Policy. Retrieved September 5, 2010.

- 1 2 Knott, Stephen. "GEORGE H. W. BUSH: IMPACT AND LEGACY". Miller Center. University of Virginia.

- ↑ "Modest Bush Approval Rating Boost at War's End: Summary of Findings – Pew Research Center for the People & the Press". People-press.org. Retrieved September 5, 2010.

- ↑ "George H. W. Bush". American Experience. PBS. October 3, 1990. Retrieved September 5, 2010.

- ↑ "Maybe I'm Amazed". Snopes.com. April 1, 2001. Archived from the original on May 27, 2012. Retrieved April 11, 2008.

- ↑ Rosenthal, Andrew (February 5, 1992). "Bush Encounters the Supermarket, Amazed". The New York Times. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ↑ Langer, Gary (January 17, 2001). "Poll: Clinton Legacy Mixed". ABC News. Retrieved April 11, 2008.

- ↑ "George H. W. Bush: Life in Brief". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ↑ Paul Steinhauser. "CNN, Views soften on 2 former presidents, CNN poll finds". CNN. Retrieved September 5, 2010.

- ↑ Shesol, Jeff (November 13, 2015). "What George H. W. Bush Got Wrong". New Yorker. Retrieved August 30, 2016.

- ↑ Rottinghaus, Brandon; Vaughn, Justin S. (19 February 2018). "How Does Trump Stack Up Against the Best — and Worst — Presidents?". New York Times. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- ↑ "Presidential Historians Survey 2017". C-Span. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- ↑ Greene, pp. 255–256

- ↑ Greene, pp. 258–259

- ↑ Greene, pp. 108–110

Works cited

- Herring, George C. (2008). From Colony to Superpower; U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507822-0.

- Greene, John Robert (2015). The Presidency of George Bush (2nd ed.). Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-2079-1.

- Naftali, Timothy (2007). George H. W. Bush. Times Books. ISBN 0-8050-6966-6.

- Patterson, James (2005). Restless Giant: The United States from Watergate to Bush v. Gore. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195122169.

- Waterman, Richard W. (1996). "Storm Clouds on the Political Horizon: George Bush at the Dawn of the 1992 Presidential Election". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 26 (2): 337349. JSTOR 27551581.

- Wilentz, Sean (2008). The Age of Reagan. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-074480-9.

Further reading

- Meacham, Jon (2015). Destiny and Power: The American Odyssey of George Herbert Walker Bush. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6765-7.

- Podhoretz, John (1993). Hell of a Ride: Backstage at the White House Follies, 1989–1993. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-79648-8.

- Rossinow, Douglas C. (2015). The Reagan Era: A History of the 1980s. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231538657.

- Smith, Jean Edward (1992). George Bush's War. New York: Henry Holt & Company. ISBN 0-8050-1388-1.

- Sununu, John H. (2015). The Quiet Man: The Indispensable Presidency of George H. W. Bush. Broadside Books. ISBN 978-0-06-238428-7.

- Updegrove, Mark K. (2017). The Last Republicans: Inside the Extraordinary Relationship between George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush. Harper. ISBN 9780062654120.

- Wicker, Tom (2004). George Herbert Walker Bush. Lipper/Viking. ISBN 0670033030.