Roger Williams

| Roger Williams | |

|---|---|

Roger Williams statue by Franklin Simmons | |

| 9th President of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations | |

|

In office 1654–1657 | |

| Preceded by | Nicholas Easton |

| Succeeded by | Benedict Arnold |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

21 December 1603 London, England |

| Died |

between 27 January and 15 March 1683 (aged 79) Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Barnard |

| Children | 6 |

| Alma mater | Pembroke College, Cambridge |

| Occupation | Minister, statesman, author |

| Signature |

|

Roger Williams (c. 21 December 1603 – between 27 January and 15 March 1683)[1] was a Puritan minister, theologian, and author who founded the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. He was a staunch advocate for religious freedom, separation of church and state, and fair dealings with American Indians, and he was one of the first abolitionists.[2][3]

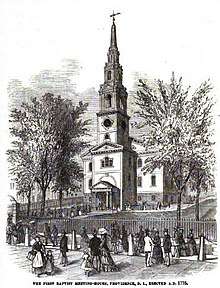

Williams was expelled by the Puritan leaders from the Massachusetts Bay Colony for spreading "new and dangerous ideas", and he established the Providence Plantations in 1636 as a refuge offering what he called "liberty of conscience". In 1638, he founded the First Baptist Church in America, also known as the First Baptist Church of Providence.[4][5] He was a student of Indian languages, and he organized the first attempt to prohibit slavery in any of the American colonies.[3]

Early life

Roger Williams was born in London around 1603, though the exact date is unknown because his birth records were destroyed in the Great Fire of London of 1666 when St Sepulchre's Church was burned.[6][7][8][9] His father James Williams (1562–1620) was a merchant tailor in Smithfield, and his mother was Alice Pemberton (1564–1635). He had a spiritual conversion at an early age, of which his father disapproved.

As a teen, Williams was apprenticed under Sir Edward Coke (1552–1634) the famous jurist. He was educated at Charterhouse School under Coke's patronage, and also at Pembroke College, Cambridge (Bachelor of Arts, 1627).[10] He seemed to have a gift for languages and early acquired familiarity with Latin, Hebrew, Greek, Dutch, and French. Years later, he tutored John Milton in Dutch in exchange for refresher lessons in Hebrew.[11]

Williams took holy orders in the Church of England in connection with his studies, but he became a Puritan at Cambridge and thus ruined his chance for preferment in the Anglican church. After graduating from Cambridge, he became the chaplain to Sir William Masham. He married Mary Barnard (1609–76) on 15 December 1629 at the Church of High Laver, Essex, England. They ultimately had six children, all born in America: Mary, Freeborn, Providence, Mercy, Daniel, and Joseph.

Williams knew that Puritan leaders planned to migrate to the New World. He did not join the first wave, but he decided before the year ended that he could not remain in England under Archbishop William Laud's rigorous administration. He regarded the Church of England as corrupt and false, and he had arrived at the Separatist position by the time that he and his wife boarded the Lyon in early December, 1630.[12]

Life in America

The Boston church offered Williams a post in 1631 filling in for Rev. John Wilson[3] while Wilson returned to England to fetch his wife. However, Williams declined the position on grounds that it was "an unseparated church". In addition, he asserted that civil magistrates must not punish any sort of "breach of the first table" of the Ten Commandments such as idolatry, Sabbath-breaking, false worship, and blasphemy, and that individuals should be free to follow their own convictions in religious matters. These three principles became central to his teachings and writings: separatism, liberty of conscience, and separation of church and state.

Salem and Plymouth

As a Separatist, Williams considered the Church of England irredeemably corrupt and believed that one must completely separate from it to establish a new church for the true and pure worship of God. The Salem church was also inclined to Separatism, and they invited him to become their teacher. The leaders in Boston vigorously protested, and Salem withdrew its offer. As the summer of 1631 ended, Williams moved to Plymouth Colony where he was welcomed, and he informally assisted the minister there. He regularly preached and, according to Governor William Bradford, "his teachings were well approved".

After a time, Williams decided that the Plymouth church was not sufficiently separated from the Church of England. Furthermore, his contact with the Narragansett Indians had caused him to question the validity of the colonial charters that did not include legitimate purchase of Indian land. Governor Bradford later wrote that Williams fell "into some strange opinions which caused some controversy between the church and him".[13] In December 1632, Williams wrote a lengthy tract that openly condemned the King's charters and questioned the right of Plymouth to the land without first buying it from the Indians. He even charged that King James had uttered a "solemn lie" in claiming that he was the first Christian monarch to have discovered the land. Williams moved back to Salem by the fall of 1633 and was welcomed by Rev. Samuel Skelton as an unofficial assistant.

Litigation and exile

The Massachusetts Bay authorities were not pleased at Williams' return. In December 1633, they summoned him to appear before the General Court in Boston to defend his tract attacking the King and the charter. The issue was smoothed out, and the tract disappeared forever, probably burned. In August 1634, Williams became acting pastor of the Salem church, the Rev. Skelton having died. In March 1635, he was again ordered to appear before the General Court, and he was summoned yet again for the Court's July term to answer for "erroneous" and "dangerous opinions". The Court finally ordered that he be removed from his church position.

This latest controversy welled up as the town of Salem petitioned the General Court to annex some land on Marblehead Neck. The Court refused to consider the request unless the church in Salem removed Williams. The church felt that this order violated their independence, and sent a letter of protest to the other churches. However, the letter was not read publicly in those churches, and the General Court refused to seat the delegates from Salem at the next session. Support for Williams began to wane under this pressure, and he withdrew from the church and began meeting with a few of his most devoted followers in his home.

Finally, in October 1635, the General Court tried Williams and convicted him of sedition and heresy. They declared that he was spreading "diverse, new, and dangerous opinions" [14] and ordered that he be banished. The execution of the order was delayed because Williams was ill and winter was approaching, so he was allowed to stay temporarily, provided that he ceased publicly teaching his opinions. He failed to do so, and the sheriff came in January 1636, only to discover that he had slipped away three days earlier during a blizzard. He traveled 55 miles through the deep snow, from Salem to Raynham, Massachusetts where the local Wampanoags offered him shelter at their winter camp. Their Sachem Massasoit hosted Williams for the three months until spring.

Settlement at Providence

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the United States |

|

|

|

In the spring of 1636, Williams and a number of others from Salem began a new settlement on land which he had bought from Massasoit in Rumford, Rhode Island. However, Plymouth authorities asserted that he was within their land grant and were concerned that his presence there might anger the leaders of Massachusetts Bay Colony. Williams and his friends had already planted their crops, but they decided to move across the Seekonk River just the same, as that territory lay beyond any charter. They rowed across and encountered Narragansett Indians who greeted them with the phrase, "What cheer, Neetop" (hello, friend). Williams acquired land from Canonicus and Miantonomi, chief sachems of the Narragansetts. He and 12 "loving friends" then established a new settlement which Williams called "Providence" because he felt that God's Providence had brought them there.[15] Williams named his third child Providence, the first to be born in the new settlement.

Williams wanted his settlement to be a haven for those "distressed of conscience", and it soon attracted a collection of dissenters and otherwise-minded individuals. From the beginning, a majority vote of the heads of households governed the new settlement, but only in civil things. Newcomers could also be admitted to full citizenship by a majority vote. In August 1637, a new town agreement again restricted the government to civil things. In 1640, 39 freemen (men who had full citizenship and voting rights) signed another agreement which declared their determination "still to hold forth liberty of conscience". Thus, Williams founded the first place in modern history where citizenship and religion were separate, providing religious liberty and separation of church and state. This was combined with the principle of majoritarian democracy.

In November 1637, the General Court of Massachusetts disarmed, disenfranchised, and forced into exile some of the Antinomians, including the followers of Anne Hutchinson. John Clarke was among them, and he learned from Williams that Rhode Island might be purchased from the Narragansetts; Williams helped him to make the purchase, along with William Coddington and others, and they established the settlement of Portsmouth. In spring 1638, some of those settlers split away and founded the nearby settlement of Newport, also situated on Rhode Island (which is today called Aquidneck Island).

Pequot War and relations with Indians

In the meantime, the Pequot War had broken out. Massachusetts Bay asked for Williams' help, which he gave despite his exile, and he became the Bay colony's eyes and ears, and also dissuaded the Narragansetts from joining with the Pequots. Instead, the Narragansetts allied themselves with the Colonists and helped to crush the Pequots in 1637–38. The Narragansetts thus became the most powerful Indian tribe in southern New England.

Williams formed firm friendships and developed deep trust among the Indian tribes, especially the Narragansetts. He was able to keep the peace between the Indians and the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations for nearly 40 years by his constant mediation and negotiation. He twice surrendered himself as a hostage to the Indians to guarantee the safe return of a great sachem from a summons to a court: Pessicus in 1645 and Metacom ("King Philip") in 1671. Williams was trusted by the Indians more than any other Colonist, and he proved trustworthy.

However, the other New England colonies began to fear and mistrust the Narragansetts, and soon came to regard the Rhode Island colony as a common enemy. In the next three decades, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Plymouth exerted pressure to destroy both Rhode Island and the Narragansetts. In 1643, the neighboring colonies formed a military alliance called the United Colonies which pointedly excluded the towns around Narragansett Bay. The object was to put an end to the heretic settlements, which they considered an infection. In response, Williams traveled to England to secure a charter for the colony.

Return to England and charter matters

Williams arrived in London in the midst of the English Civil War. Puritans held power in London, and he was able to obtain a charter through the offices of Sir Henry Vane the Younger, despite strenuous opposition from Massachusetts' agents. His first published book A Key into the Language of America (1643) proved crucial to the success of his charter, albeit indirectly.[16][17] It combined a phrase-book with observations about life and culture as an aid to communicate with the Indians of New England, covering everything from salutations to death and burial. Williams also sought to correct English attitudes of superiority toward the American Indians:

Boast not proud English, of thy birth & blood;

Thy brother Indian is by birth as Good.

Of one blood God made Him, and Thee and All,

As wise, as fair, as strong, as personal.

Key was the first dictionary of any Indian language, and it fed the great curiosity of English people about the American Indians. It was printed by John Milton's publisher Gregory Dexter who had become a resident of Providence Plantations, and it quickly became a bestseller and provided Williams with a large and favorable reputation.

Williams secured his charter from Parliament for Providence Plantations in July 1644, after which he published his most famous book The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience. This produced a great uproar, and Parliament responded in August by ordering the public hangman to burn all copies—but Williams himself was already on his way back to New England.

It took Williams several years to get the four towns around Narragansett Bay to unite under a single government because of William Coddington's opposition on Aquidneck Island (which they called Rhode Island at the time), but the four settlements finally united in 1647 into the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Freedom of conscience was again proclaimed, and the colony became a safe haven for people who were persecuted for their beliefs, including Baptists, Quakers, and Jews. Still, the divisions between the towns and among powerful personalities did not bode well for the colony. Coddington never liked Williams, nor did he like being subordinated to the new charter government. He sailed to England and returned to Rhode Island in 1651 with his own patent making him "Governor for Life" over Aquidneck Island and Conanicut Island.

As a result, Providence, Warwick, and Coddington's opponents on Aquidneck dispatched Roger Williams and John Clarke to England to get Coddington's commission canceled. Williams sold his trading post at Cocumscussec (near Wickford, Rhode Island) to pay for his journey even though it was his main source of income. He and Clarke succeeded in getting Coddington's patent rescinded, and Clarke remained in England for the next decade to protect the colonists' interests and secure a new charter. Williams returned to America in 1654 and was immediately elected the colony's President. He subsequently served in many offices in town and colonial governments.

In 1641, Massachusetts Bay Colony passed the first laws to make slavery legal in the colonies, and these laws were applied in Plymouth and Connecticut with the creation of the United Colonies in 1643. Roger Williams and Samuel Gorton both opposed slavery, and Providence Plantations (Providence and Warwick) passed a law on 18 May 1652 intended to prevent slavery in the colony during the time when Coddington's followers had separated from Providence. However, when the four towns of the colony were reunited, the Aquidneck towns refused to accept this law, making it a dead letter.[18] For the next century, Newport was the economic and political center of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, and that town disregarded the anti-slavery law. Instead, Newport entered the African slave trade in 1700, after Williams' death, and became the leading port for American ships carrying slaves in the colonial American triangular trade until the American Revolutionary War.[19]

Relations with the Baptists

Ezekiel Holliman baptized Williams in late 1638. A few years later, Dr. John Clarke established the First Baptist Church in Newport, Rhode Island, and both Roger Williams and John Clarke became the founders of the Baptist faith in America.[20] Williams did not affiliate himself with any church, but he remained interested in the Baptists, agreeing with their rejection of infant baptism and most other matters. Both enemies and admirers sometimes called him a "Seeker", associating him with a heretical movement that accepted Socinianism and Universal Reconciliation, but Williams rejected both of these ideas.[21]

King Philip's War and death

King Philip's War (1675–1676) pitted the colonists against Indians with whom Williams had good relations in the past. Williams, although in his 70s, was elected captain of Providence's militia. That war proved to be one of the bitterest events in his life, as his efforts ended with the burning of Providence in March 1676, including his own house.

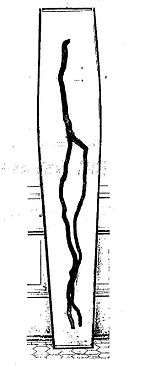

Williams died in 1683 sometime between January and March and was buried on his own property. Fifty years later, his house collapsed into the cellar and the location of his grave was forgotten. According to the National Park Service, in 1860, Providence residents determined to raise a monument in his honor "dug up the spot where they believed the remains to be, they found only nails, teeth, and bone fragments. They also found an apple tree root" which they thought followed the shape of a human body; the root followed the shape of a spine, split at the hips, bent at the knees, and turned up at the feet.[22] The Rhode Island Historical Society has cared for this tree root since 1860 as representative of Rhode Island's founder, and has had it on display in the John Brown House since 2007.[23]

Separation of church and state

Williams was a staunch advocate of separation of church and state. He was convinced that there was no scriptural basis for a state church, and historian Timothy Hall suggests that Williams had arrived at this conclusion before landing in Boston in 1631.[24] He declared that the state should concern itself only with matters of civil order, not with religious belief, and he rejected any attempt to enforce the "first Table" of the Ten Commandments, those commandments that dealt with the relationship between God and individuals. Instead, Williams believed that the state must confine itself to the commandments dealing with the relations between people: murder, theft, adultery, lying, and honoring parents.[25] He employed the metaphor of a "wall of separation" between church and state, which was later used by Thomas Jefferson in his Letter to Danbury Baptists (1801).[26][27]

Williams considered it "forced worship" if the state attempted to promote any particular religious idea or practice, and he declared, "Forced worship stinks in God's nostrils."[28] He considered Constantine the Great to be a worse enemy to Christianity than Nero because the subsequent state support corrupted Christianity and led to the death of the Christian church. He described the attempt to compel belief as "rape of the soul" and spoke of the "oceans of blood" shed as a result of trying to command conformity.[29] The moral principles in the Scriptures ought to inform the civil magistrates, he believed, but he observed that well-ordered, just, and civil governments existed even where Christianity was not present. Thus, all governments had to maintain civil order and justice, but Williams decided that none had a warrant to promote or repress any religion. Most of his contemporaries criticized his ideas as a prescription for chaos and anarchy, and the vast majority believed that each nation must have its national church and could require that dissenters conform.

Writings

Williams's career as an author began with A Key into the Language of America (London, 1643), written during his first voyage to England. His next publication was Mr. Cotton's Letter lately Printed, Examined and Answered (London, 1644; reprinted in Publications of the Narragansett Club, vol. ii, along with John Cotton's letter which it answered). His most famous work is The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience (published in 1644), considered by some to be one of the best defenses of liberty of conscience.[30]

An anonymous pamphlet was published in London in 1644 entitled Queries of Highest Consideration Proposed to Mr. Tho. Goodwin, Mr. Phillip Nye, Mr. Wil. Bridges, Mr. Jer. Burroughs, Mr. Sidr. Simpson, all Independents, etc. which is now ascribed to Williams. These "Independents" were members of the Westminster Assembly; their Apologetical Narration sought a way between extreme Separatism and Presbyterianism, and their prescription was to accept the state church model of Massachusetts Bay.

Williams published The Bloody Tenent yet more Bloudy: by Mr. Cotton's Endeavor to wash it white in the Blood of the Lamb; of whose precious Blood, spilt in the Bloud of his Servants; and of the Blood of Millions spilt in former and later Wars for Conscience sake, that most Bloody Tenent of Persecution for cause of Conscience, upon, a second Tryal is found more apparently and more notoriously guilty, etc. (London, 1652) during his second visit to England. This work reiterated and amplified the arguments in Bloudy Tenent, but it has the advantage of being written in answer to Cotton's A Reply to Mr. Williams his Examination (Publications of the Narragansett Club, vol. ii.).

Other works by Williams include:

- The Hireling Ministry None of Christ's (London, 1652)

- Experiments of Spiritual Life and Health, and their Preservatives (London, 1652; reprinted Providence, 1863)

- George Fox Digged out of his Burrowes (Boston, 1676). (discusses Quakerism with its different belief in the "inner light," which Williams considered heretical.)

A volume of his letters is included in the Narragansett Club edition of Williams' Works (7 vols., Providence, 1866–74), and a volume was edited by J. R. Bartlett (1882).

- The Correspondence of Roger Williams, 2 vols., Rhode Island Historical Society, 1988, edited by Glenn W. LaFantasie.

Brown University's John Carter Brown Library has long housed a 234-page volume referred to as the "Roger Williams Mystery Book".[31] The margins of this book are filled with notations in handwritten code, believed to be the work of Roger Williams. In 2012, Brown University undergraduate Lucas Mason-Brown cracked the code and uncovered conclusive historical evidence attributing its authorship to Williams.[32] Translations are revealing transcriptions of a geographical text, a medical text, and 20 pages of original notes addressing the issue of infant baptism.[33] Mason-Brown has since discovered more writings by Williams employing a separate code in the margins of a rare edition of Eliot's Indian Bible.[34]

Legacy

.jpg)

Williams' legacy has grown over time with changing values.

His defense of American Indians, accusations that Puritans had reproduced the "evils" of the Anglican Church, and his denial that the king had authority to grant charters for colonies put him at the center of nearly every political debate during his life.

By the time of American independence, moreover, he was considered a defender of religious freedom. He has continued to be praised by generations of historians as a unique figure in early colonial history and a key influence on the Founding Fathers.

Tributes to Williams include:

- Roger Williams National Memorial is a park in downtown Providence established in 1965

- Roger Williams Park, Providence, Rhode Island, and the Roger Williams Park Zoo within it

- Roger Williams University in Bristol, Rhode Island

- Roger Williams Dining Hall at the University of Rhode Island

- Roger Williams Inn, the main dining hall at the American Baptists' Green Lake Conference Center, founded in 1943 in Green Lake, Wisconsin

- Williams was selected in 1872 to represent Rhode Island in the National Statuary Hall Collection in the United States Capitol

- Williams is depicted on the International Monument to the Reformation in Geneva, along with other prominent reformers

- Williams is honored with a feast day on the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church on 5 February

- Roger Williams at Find a Grave

See also

References

- ↑ "Roger Williams (American religious leader)". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ↑ "Roger Williams". History.com. A&E Television Networks. 2009. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- 1 2 3 Barry, John M. (January 2012). "God, Government and Roger Williams' Big Idea". Smithsonian. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ↑ "Our History". American Baptist Churches USA. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ↑ "First Baptist Meetinghouse, 75 North Main Street, Providence, Providence County, RI". Library of Congress.

- ↑ William Gammell, Life of Roger Williams, the Founder of the State of Rhode Island, Boston: Gould and Lincoln, 59 Washington Street. 1854

- ↑ Romeo Elton, Life of Roger Williams, the earliest Legislator and true Champion for a Full and Absolute Liberty of Conscience, London: Albert Cockshaw, 41, Ludgate Hill. New York: G.P. Putnam London: Miall and Cockhaw, Printers, Horse-Shoe Court, Ludgate Hill

- ↑ James D. Knowles, Memoir of Roger Williams the Founder of the State of Rhode-Island, Boston: Lincoln, Edmands and Co. 1834 Lewis & Penniman, Printers. Bromfield-street.

- ↑ Rev. Z.A. Mudge, Foot-Prints of Roger Williams: A Biography, with sketches of important events in early New England History, with which he was connected, New York: Carlton & Lanahan. San Francisco: E. Thomas. Cincinnati: Hitchcock & Waldon. Sunday-School Department. (Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1871)

- ↑ "Williams, Roger (WLMS623R)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ↑ Pfeiffer, Robert H. (April 1955). "The Teaching of Hebrew in Colonial America". The Jewish Quarterly Review. pp. 363–73. JSTOR 1452938.

- ↑ "A Brief history of Jacob Belfry" Page 40, 1888

- ↑ Quoted in Edwin Gaustad,Liberty of Conscience: Roger Williams in America Judson Press, 1999, p. 28.

- ↑ LaFantasie, Glenn W., ed. The Correspondence of Roger Williams, University Press of New England, 1988, Vol. 1, pp.12–23.

- ↑ An Album of Rhode Island History by Patrick T. Conley

- ↑ Gaustad, Edwin S.,Liberty of Conscience (Judson Press, 1999), p. 62

- ↑ Ernst, Roger Williams: New England Firebrand (Macmillan, 1932), p. 227-228

- ↑ McLoughlin, William G. Rhode Island: A History (W.W. Norton, 1978), p. 26.

- ↑ Coughtry, Jay, The Notorious Triangle: Rhode Island and the African Slave Trade, 1700–1807 (Temple University Press, 1981).

- ↑ "Newport Notables". Redwood Library. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

- ↑ Clifton E. Olmstead (1960): History of Religion in the United States. Englewood Cliffs, N.J., p. 106

- ↑ Bryant, Sparkle (19 October 2015). "The Tree Root That Ate Roger Williams". NPS News Releases. National Park Service. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ↑ Rhode Island Historical Society, "Body, Body, Who's Got the Body? Where in the World IS Roger Williams", New and Notes, (Spring/Winter, 2008), p. 4.

- ↑ Timothy Hall (1998). Separating Church and State: Roger Williams and Religious Liberty. University of Illinois Press. p. 72.

- ↑ Hall (1998). Separating Church and State: Roger Williams and Religious Liberty. p. 77.

- ↑ Barry, John M. (January 2012). "God, Government and Roger Williams' Big Idea". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- ↑ "Everson and the Wall of Separation". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. Pew Research Center. 14 May 2009. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ↑ Lemons, Stanley. "Roger Williams Champion of Religious Liberty". Providence, RI City Archives.

- ↑ Chana B. Cox (2006). Liberty: God's Gift to Humanity. Lexington Books. p. 26.

- ↑ James Emanuel Ernst, Roger Williams, New England Firebrand (Macmillan Co., Rhode Island, 1932), pg. 246

- ↑ Mason-Brown, Lucas. "Cracking the Code: Infant Baptism and Roger Williams". JCB Books Speak. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- ↑ Fischer, Suzanne. "Personal Tech for the 17th Century". The Atlantic. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- ↑ McKinney, Michael (March 2012). "Reading Outside the Lines" (PDF). The Providence Journal. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- ↑ Mason-Brown, Lucas. "Cracking the Code: Infant Baptism and Roger Williams". JCB Books Speak. Brown University. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

Further reading

- Barry, John, Roger Williams and the Creation of the American Soul (New York: Viking Press, 2012).

- Bejan, Teresa, Mere Civility: Disagreement and the Limits of Toleration (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017). Addresses Roger Williams' ideas in dialogue with Hobbes and Locke, and suggests lessons from Williams for how to disagree well in the modern public sphere.

- Brockunier, Samuel. The Irrepressible Democrat, Roger Williams, (1940), popular biography

- Burrage, Henry S. "Why Was Roger Williams Banished?" American Journal of Theology 5 (January 1901): 1–17.

- Byrd, James P., Jr. The Challenges of Roger Williams: Religious Liberty, Violent Persecution, and the Bible (2002). 286 pp.

- Davis. Jack L. "Roger Williams among the Narragansett Indians", New England Quarterly, Vol. 43, No. 4 (Dec. 1970), pp. 593–604 in JSTOR

- Field, Jonathan Beecher. "A Key for the Gate: Roger Williams, Parliament, and Providence", New England Quarterly 2007 80(3): 353–382

- Goodman, Nan. "Banishment, Jurisdiction, and Identity in Seventeenth-Century New England: The Case of Roger Williams", Early American Studies, An Interdisciplinary Journal Spring 2009, Vol. 7 Issue 1, pp 109–39.

- Gaustad, Edwin, S. Roger Williams (Oxford University Press, 2005). 140 pp. short scholarly biography stressing religion

- Gaustad, Edwin, S., Liberty of Conscience: Roger Williams in America. (Judson Press, Valley Forge, 1999).

- Hall, Timothy L. Separating Church and State: Roger Williams and Religious Liberty (1998). 206 pp.

- Johnson, Alan E. The First American Founder: Roger Williams and Freedom of Conscience (Pittsburgh, PA: Philosophia Publications, 2015). In-depth discussion of Roger Williams's life and work and his influence on the US Founders and later American history.

- Miller, Perry, Roger Williams, A Contribution to the American Tradition, (1953). much debated study; Miller argues that Williams thought was primarily religious, not political as so many of the historians of the 1930s and 1940s had argued.

- Morgan, Edmund S. Roger Williams: the church and the state (1967) 170 pages; short biography by leading scholar

- Neff, Jimmy D. "Roger Williams: Pious Puritan and Strict Separationist", Journal of Church and State 1996 38(3): 529–546 in EBSCO

- Phillips, Stephen. "Roger Williams and the Two Tables of the Law", Journal of Church and State 1996 38(3): 547–568 in EBSCO

- Skaggs, Donald. Roger Williams' Dream for America (1993). 240 pp.

- Stanley, Alison. "'To Speak With Other Tongues': Linguistics, Colonialism and Identity in 17th Century New England", Comparative American Studies March 2009, Vol. 7 Issue 1, p1, 17p

- Winslow, Ola Elizabeth, Master Roger Williams, A Biography. (1957) standard biography

- Wood, Timothy L. "Kingdom Expectations: The Native American in the Puritan Missiology of John Winthrop and Roger Williams", Fides et Historia 2000 32(1): 39–49

Historiography

- Carlino, Anthony O. "Roger Williams and his Place in History: The Background and the Last Quarter Century", Rhode Island History 2000 58(2): 34–71, historiography

- Irwin, Raymond D. "A Man for all Eras: The Changing Historical Image of Roger Williams, 1630–1993", Fides Et Historia 1994 26(3): 6–23, historiography

- Morgan, Edmund S. " Miller's Williams", New England Quarterly, Vol. 38, No. 4 (Dec. 1965), pp. 513–523 in JSTOR

- Moore, Leroy, Jr. "Roger Williams and the Historians", Church History 1963 32(4): 432–451 in JSTOR

- Peace, Nancy E. "Roger Williams: A Historiographical Essay", Rhode Island History 1976 35(4): 103–113,

Primary sources

- William, Roger. The Complete Writings of Roger Williams (7 vol; 1963)

- William, Roger. The Correspondence of Roger Williams. Vol. 1: 1629–1653. Vol. 2: 1654–1682 ed. by Glenn W. LaFantasie. (1988) 867 pp.

Fiction

- Settle, Mary Lee, I, Roger Williams: A Novel, W. W. Norton & Company, Reprint edition (2002).

- George, James W., The Prophet and the Witch: A Novel of Puritan New England, Amazon Digital Services (2017).

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Williams, Roger. |

- Literature by and about Roger Williams in the German National Library catalogue

- "Roger Williams". Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) (in German).

- Works by or about Roger Williams at Internet Archive

- Side of the US-American Roger Williams circle of friends

- Documentary about Roger Williams life: Roger Williams – Freedom's Forgotten Hero (Part 1 to 7)

- Lecture by Martha Nussbaum: Equal Liberty of Conscience: Roger Williams and the Roots of a Constitutional Tradition

- Chronological list of Rhode Island leaders