Presidency of Woodrow Wilson

| Presidency of Woodrow Wilson | |

|---|---|

| |

| In office | |

| March 4, 1913 – March 4, 1921 | |

| Preceded by | Taft presidency |

| Succeeded by | Harding presidency |

| Seat | White House, Washington, D.C. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| ||

|---|---|---|

President of the United States

First Term

Second Term

World War I

|

||

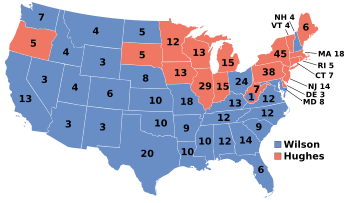

The presidency of Woodrow Wilson began on March 4, 1913 at noon when Woodrow Wilson was inaugurated as President of the United States, and ended on March 4, 1921. Wilson, a Democrat, took office as the 28th U.S. President after winning the 1912 presidential election, gaining a large majority in the Electoral College and a 42% plurality of the popular vote in a four–candidate field. Wilson was re-elected in 1916, defeated Republican Charles Evans Hughes by a fairly narrow margin. He was the first Southerner to be elected president since Zachary Taylor in 1848,[1] and only the second person to hold the Democrat ticket since 1860.

Wilson was a leading force in the Progressive Movement, and during his first term, he oversaw the passage of progressive legislative policies unparalleled until the New Deal in the 1930s. Taking office one month after the ratification of the 16th Amendment of the Constitution permitted a federal income tax, he helped pass the Revenue Act of 1913, which reintroduced a federal income tax to lower tariff rates. Other major progressive legislations passed during Wilson's first term include the Federal Reserve Act, the Federal Trade Commission Act, the Clayton Antitrust Act, and the Federal Farm Loan Act. While passing of the Adamson Act — which imposed an 8-hour workday for railroads, he averted a railroad strike and an ensuing economic crisis. Wilson's administration also allowed segregationist policies in government agencies. Upon the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Wilson maintained a policy of neutrality, while pursuing a moralistic policy in dealing with Mexico's civil war.

Wilson's second term was dominated by the America's entry into World War I and that war's aftermath. In April 1917, when Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare, Wilson asked Congress to declare war in order to make "the world safe for democracy." Through the Selective Service Act, conscription sent 10,000 freshly trained soldiers to France per day by summer 1918. On the home front, Wilson raised income taxes, set up the War Industries Board, promoted labor union cooperation, regulated agriculture and food production through the Lever Act, and nationalized the nation's railroad system. In his 1915 State of the Union, Wilson asked Congress for what became the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918, suppressing anti-draft activists. The crackdown was later intensified by Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer to include expulsion of non-citizen radicals during the First Red Scare of 1919–1920. Wilson infused morality into his internationalism, an ideology now referred to as "Wilsonian"—an activist foreign policy calling on the nation to promote global democracy.[2][3] In early 1918, he issued his principles for peace, the Fourteen Points, and in 1919, following the signing of an armistice with Germany, he traveled to Paris, concluding the Treaty of Versailles. Wilson embarked on a nationwide tour to campaign for the treaty, which would have included U.S. entrance into the League of Nations, but was left incapacitated by a stroke in October 1919 and saw the treaty defeated in the Senate.

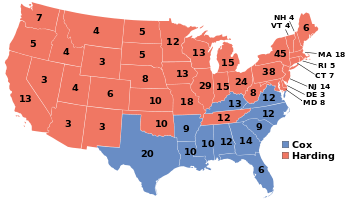

Despite grave doubts about his health and mental capacity, Wilson served the remainder of his second term and unsuccessfully sought his party's nomination for a third term. In the 1920 presidential election, Republican Warren G. Harding defeated Democratic nominee James M. Cox in a landslide, and Harding succeeded Wilson in March 1921. Historians and political scientists rank Wilson as an above-average president, and his presidency was an important forerunner of modern American liberalism. However, Wilson has also been criticized for his racist views and actions.

Presidential election of 1912

Wilson became a prominent 1912 presidential contender immediately upon his election as Governor of New Jersey in 1910, and his clashes with state party bosses enhanced his reputation with the rising Progressive movement.[4] Prior to the 1912 Democratic National Convention, Wilson made a special effort to win the approval of three-time Democratic presidential nominee William Jennings Bryan, whose followers had largely dominated the Democratic Party since the 1896 presidential election.[5] Speaker of the House Champ Clark of Missouri was viewed by many as the front-runner for the nomination, while House Majority Leader Oscar Underwood of Alabama also loomed as a challenger. Clark found support among the Bryan wing of the party, while Underwood appealed to the conservative Bourbon Democrats, especially in the South.[6] On the first ballot of the Democratic National Convention, Clark won a plurality of delegates, and on the tenth ballot, he won a majority of the delegates after the New York Tammany Hall machine swung behind him. However, the Democratic Party required a nominee to win two-thirds of the delegates to win the nomination, and balloting continued.[7] The Wilson campaign picked up delegates by promising the vice presidency to Governor Thomas R. Marshall of Indiana, and several Southern delegations shifted their support from Underwood to Wilson, a native Southerner. Wilson finally won two-thirds of the vote on the convention's 46th ballot, and Marshall became Wilson's running mate.[8]

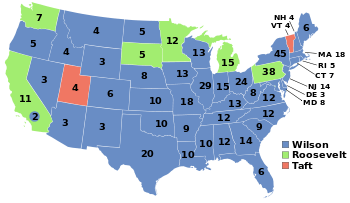

Wilson faced two major opponents in the 1912 general election: one-term Republican incumbent William Howard Taft, and former Republican President Theodore Roosevelt, who ran a third party campaign as the "Bull Moose" Party nominee. A fourth candidate, Eugene V. Debs of the Socialist Party, would also win a significant share of the popular vote. Roosevelt had broken with his former party at the 1912 Republican National Convention after Taft narrowly won re-nomination, and the split in the Republican Party made Democrats hopeful that they could win the presidency for the first time since the 1892 presidential election.[9] Roosevelt emerged as Wilson's main challenger, and Wilson and Roosevelt largely campaigned against each other despite sharing similarly progressive platforms that called for a strong, interventionist central government.[10] Wilson won 435 of the 531 electoral votes and 41.8% of the popular vote, while Roosevelt won most of the remaining electoral votes and 27.4% of the popular vote, representing one of the strongest third party performances in U.S. history. Taft won 23.2% of the popular vote but just 8 electoral votes, while Debs won 6% of the popular vote. In the concurrent congressional elections, Democrats retained control of the House and won a majority in the Senate. Wilson's victory made him the first Southerner to win the presidency since the Civil War.[11]

Personnel and appointments

Cabinet and administration

| The Wilson Cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Woodrow Wilson | 1913–1921 |

| Vice President | Thomas R. Marshall | 1913–1921 |

| Secretary of State | William J. Bryan | 1913–1915 |

| Bainbridge Colby | 1920–1921 | |

| Robert Lansing | 1915–1920 | |

| Secretary of Treasury | William G. McAdoo | 1913–1918 |

| David F. Houston | 1920–1921 | |

| Carter Glass | 1918–1920 | |

| Secretary of War | Lindley M. Garrison | 1913–1916 |

| Newton D. Baker | 1916–1921 | |

| Attorney General | James C. McReynolds | 1913–1914 |

| A. Mitchell Palmer | 1919–1921 | |

| Thomas W. Gregory | 1914–1919 | |

| Postmaster General | Albert S. Burleson | 1913–1921 |

| Secretary of the Navy | Josephus Daniels | 1913–1921 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Franklin K. Lane | 1913–1920 |

| John B. Payne | 1920–1921 | |

| Secretary of Agriculture | David F. Houston | 1913–1920 |

| Edwin T. Meredith | 1920–1921 | |

| Secretary of Commerce | William C. Redfield | 1913–1919 |

| Joshua W. Alexander | 1919–1921 | |

| Secretary of Labor | William B. Wilson | 1913–1921 |

After the election, Wilson quickly chose William Jennings Bryan as Secretary of State, and Bryan offered advice on the remaining members of Wilson's cabinet.[12] William Gibbs McAdoo, a prominent Wilson supporter who would marry Wilson's daughter in 1914, became Secretary of the Treasury, while James Clark McReynolds, who had successfully prosecuted prominent anti-trust cases, was chosen as Attorney General. On the advice of Underwood, Wilson appointed Texas Congressman Albert S. Burleson as Postmaster General.[13] Bryan resigned in 1915 due to his opposition to Wilson hard line towards Germany in the aftermath of the Sinking of the RMS Lusitania.[14] Bryan was replaced by Robert Lansing, and Wilson took more direct control of his administration's foreign policy after Bryan's departure.[15] Bryan continued to oppose the war after leaving the cabinet, but Wilson eclipsed Bryan's standing within the Democratic Party and was able to win legislative support for his preparedness policies.[16] Newton D. Baker, a progressive Democrat, became Secretary of War in 1916, and Baker led the War Department during World War I.[17] Wilson's cabinet experienced turnover after the conclusion of World War I, with Carter Glass replacing McAdoo as Secretary of the Treasury and A. Mitchell Palmer becoming Attorney General.[18]

Wilson's chief of staff ("Secretary") was Joseph Patrick Tumulty from 1913 to 1921. Tumulty's position provided a political buffer and intermediary with the press, and his irrepressible Irish spirits offset the president's often dour Scotch disposition.[19] Wilson's first wife, Ellen Axson Wilson died on August 6, 1914.[20] Wilson married Edith Bolling Galt in 1915,[21] and she assumed full control of Wilson's schedule, diminishing Tumulty's power. The most important foreign policy advisor and confidant was "Colonel" Edward M. House until Wilson broke with him in early 1919, for his missteps at the peace conference in Wilson's absence.[22] Wilson's vice president, former Governor Thomas R. Marshall of Indiana, played little role in the administration.[23]

Press corps

Wilson fervently believe that public opinion ought to shape national policy, albeit with a few exceptions involving delicate diplomacy. Newspapers and magazines control public policy, and Wilson paid cclose attention to their needs and moves. Press secretary Joseph Patrick Tumulty proved generally effective, until Wilson's second wife began to distrust him and reduced his influence.[24] Wilson pioneered twice-weekly press conferences in the White House. Even though they were modestly effective, the president prohibited his being quoted and was particularly indeterminate in his statements.[25] The first such press conference was held on March 15, 1913, when reporters were allowed to ask him questions.[26]

Wilson had a mixed record with the press. Relations were generally smooth. The two major exceptions were ending weekly meetings with the White House correspondents after the Lusitania sinking in 1915, and sharply restricting access during the 1919 peace conference. In both cases, Wilson was afraid that publicity would interfere with his quiet diplomacy. Journalists such as Walter Lippmann found a workaround, discovering that Colonel House was both highly talkative and devious in manipulating the press to slant its stories. A major problem was that 90 percent of the major newspapers and magazine outside the South traditionally endorsed Republican. In this case the workaround was to quietly collaborate with favorable reporters Who admired Wilson's leadership in the cause of world peace; their newspapers printed their reports because their scoops made news. The German language press was vehemently hostile to Wilson, but he is that this advantage, attacking hyphenates as loyal to a foreign country.[27]

Judicial appointments

Wilson appointed three individuals to the United States Supreme Court while president. He appointed James Clark McReynolds in 1914; McReynolds would serve until 1941, becoming a member of the conservative bloc of the court.[28] After the death of Joseph Rucker Lamar in 1916, Wilson nominated Louis Brandeis to the court. Brandeis proved to be a controversial nominee, with many in the Senate opposing him to due to his progressive ideology and his religion (Brandeis was the first Jewish nominee to the Supreme Court). However, Wilson was able to convince Senate Democrats to vote for Brandeis, and he won confirmation after months of Senate consideration, serving until 1939.[29] A second vacancy arose in 1916 after the resignation of Charles Evans Hughes, and Wilson appointed John Hessin Clarke, a progressive lawyer from the electorally-important state of Ohio, to replace Hughes. Clarke would resign from the court in 1922.[30]

In addition to his three Supreme Court appointments, Wilson also appointed 20 judges to the United States Courts of Appeals and 52 judges to the United States district courts.

Domestic policy

New Freedom

With the support of the Democratic Congress, Wilson introduced a comprehensive program of domestic legislation at the outset of his administration, something no president had ever done before.[32] The newly inaugurated Wilson had four major priorities: the conservation of natural resources, banking reform, a lower tariff, and equal access to raw materials, which would be accomplished in part through the regulation of trusts.[33] Though foreign affairs would increasingly dominate his presidency starting in 1915, Wilson's first two years in office largely focused on domestic policy, and Wilson found success in implementing much of his ambitious "New Freedom" agenda.[34]

Tariff legislation

Democrats had long opposed high tariff rates, as an unfair tax on consumers. Tariff reduction was President Wilson's first priority. Even though his own party was united behind a decrease in tariff rates, most Republicans continued adhering to the party's traditional position of using high tariff rates to protect domestic manufacturing and factory workers against foreign competition. President William Howard Taft had sought to reduce rates during his presidency, but business interests had ensured that the Payne–Aldrich Tariff Act of 1909 kept high duties in place.[35] By late May 1913, House Majority Leader Oscar Underwood had passed a bill in the House that cut the average tariff rate by 10%. To cover the lost revueue, it instituted a tax on personal income above $4,000.[36] Democrats had a narrower majority in the Senate, and some Southern and Western Democrats favored the protection of the wool and sugar industries.[37] Wilson met extensively with Democratic Senators hoping marshal support for the Underwood Tariff. He also appealed directly to the people through the press. After weeks of hearings and debate, Wilson and Secretary of State Bryan managed to unite Senate Democrats behind the bill.[36] The Senate voted 44 to 37 favoring the bill, with only one Democrat voting against it and only one Republican, progressive leader Robert M. La Follette Sr., voting for it. Wilson signed the Revenue Act of 1913 (also known as the Underwood Tariff) into law on October 3, 1913.[36]

The Underwood Tariff reduced the average import tariff rates from approximately 40-26%, and it also instituted a progressive income tax with a top marginal rate of 7%.[38] Wilson later signed the Revenue Act of 1916, which further raised taxes on high earners and implemented a federal estate tax. That same year, Wilson signed a law that established the Tariff Commission, which was charged with providing expert advice on tariff rates.[39] In the 1920s, Republicans raised tariffs and lowered the income tax. Nonetheless, the policies of the Wilson administration had a durable impact on the composition of government revenue, which shifted from the tariff to the income tax.[40]

Federal Reserve System

Wilson did not wait to complete the tariff legislation to proceed with his next item of reform—banking. Countries like Britain and Germany had government-run central banks, but the United States had not had a central bank since the Bank War of the 1830s.[41] In the aftermath of the Panic of 1907, there was general agreement among leaders in both parties of the necessity to create some sort of central banking system to provide coordination during financial emergencies. Most leaders also sought currency reform, as they believed that the roughly $3.8 in coins and banknotes did not provide an adequate money supply during financial panics. Under conservative Republican Senator Nelson Aldrich's leadership, the National Monetary Commission in 1911 planned to establish a central banking system that could issue currency and would provide oversight and loans to the nation's banks. However, many progressives distrusted any plan that gave private bankers so much control over the central banking system. Relying heavily on the advice of Louis Brandeis, Wilson sought a middle ground between progressives such as Bryan and conservative Republicans like Aldrich.[42] He declared that the banking system must be "public not private, [and] must be vested in the government itself so that the banks must be the instruments, not the masters, of business."[43]

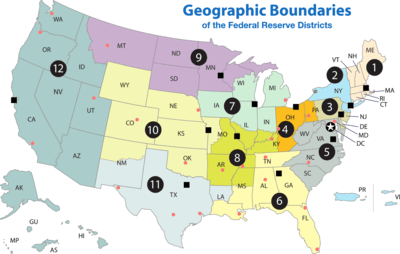

Democratic Congressmen Carter Glass and Robert L. Owen made a compromise plane on allowing the private banks to control 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks, but appeased progressives by placing controlling interest in the system in a central board that the president had appointed. Moreover, Wilson convinced Bryan's supporters thatthe plan met their demands for an elastic currency because Federal Reserve notes were obligations of the government. Having 12 regional banks, with designated geographic districts, was intended to weaken Wall Street's influence.[44] The bill passed the House in September 1913, but it faced stronger opposition in the Senate. After Wilson convinced just enough Democrats to defeat an amendment put forth by bank president Frank A. Vanderlip that would have given private banks greater control over the central banking system, the Senate voted 54–34 to approve the Federal Reserve Act. Wilson signed the bill into law in December 1913.[45]

Wilson appointed Paul Warburg and other prominent bankers to direct the new system. While power was supposed to be decentralized, the New York branch dominated the Federal Reserve as the "first among equals."[46] The new system began operations in 1915, and it played an important role in financing the Allied and American war effort in World War I.[47]

Antitrust legislation

Having passed major legislation lowering the tariff and reforming the banking structure, Wilson next sought anti-trust legislation to supplant the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890.[48] The Sherman Antitrust Act had barred any "contract, combination...or conspiracy, in restraint of trade," but had proved ineffective in preventing the rise of large business combinations known as Trusts. Roosevelt and Taft had both escalated antitrust prosecution by the Justice Department, although many progressives desired legislative reforms that would do more to prevent trusts from dominating the economy. While Roosevelt believed that trusts could be separated into "good trusts" and "bad trusts" based on their effects on the broader economy, Wilson had argued for breaking up all trusts during his 1912 presidential campaign. In December 1913, Wilson asked Congress to pass an anti-trust law that would ban many anti-competitive practices. A month later, in January 1914, he also asked for the creation of an interstate trade commission, eventually known as the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), that would preside over the dissolution of trusts but would play absolutely no role in anti-trust prosecution itself.[49]

Congressman Henry Clayton, Jr. introduced a bill that would ban several anti-competitive practices such discriminatory pricing, tying, exclusive dealing, and interlocking directorates. The bill also allowed individuals to launch anti-trust suits, and it limited the applicability of anti-trust laws on unions.[50] As the difficulty of banning all anti-competitive practices via legislation became clear, Wilson came to favor legislation granting the FTC greater discretion to investigate anti-trust violations and enforce anti-trust laws independently of the Justice Department. The Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914, which incorporated Wilson's ideas regarding the FTC, passed Congress with bipartisan support, and Wilson signed the bill into law in September 1914.[51] One month later, Wilson signed the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914, which defined several anti-competitive practices.[52]

Labor issues

President Taft had won the creation of the Commission on Industrial Relations to study labor issues, but the Senate had rejected all of his nominees to the commission. Upon taking office, Wilson nominated a mix of conservatives and progressive reformers, with commission chairman Frank P. Walsh falling into the latter group. The commission helped expose numerous labor abuses throughout the nation, and Walsh proposed reforms designed to empower unions.[53] Prior to his first presidential inauguration, Wilson had had an uneasy relationship with union leaders scu has Samuel Gompers of the American Federation of Labor, and he generally believed that workers were best protected through laws rather than unions.[54] He and Secretary of Labor William Bauchop Wilson rejected Walsh's far-reaching reforms, and instead focused on using the Labor Department to mediate conflicts between labor and ownership.[55] The labor policies of Wilson's administration were tested by a strike against the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company between late 1913 and early 1914. The company rejected the Labor Department's attempts to mediate, and a militia controlled by the company attacked a miner's camp in what became known as the Ludlow Massacre. At the Governor of Colorado's request, the Wilson administration sent in troops to end the dispute, but mediation efforts failed after the union called off the strike after a lack of funds.[56]

In mid-1916, a major railroad strike endangered the nation's economy. The president called the parties to a White House summit in August — after two days and no results, Wilson proceeded to settle the issue, using the maximum eight-hour work day as its linchpin. Congress passed the Adamson Act, which incorporating the president's proposed eight-hour work day. As a result, the strike was then cancelled. Wilson was praised for averting a national economic disaster, even though the law was received with howls from conservatives, who denounced it as a sellout to the unions and a surrender by Congress to an imperious president.[57] The Adamson Act was the first federal law that regulated hours worked by private employees.[58]

Agricultural issues

In forming his policies in agricultural, President Wilson was heavily influenced by Walter Hines Page, who favored a reorganization of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. While that department had focused on scientific research under the long tenure of James Wilson, Page favored using the department to provide education and other services directly to farmers.[59] Secretary of Agriculture David F. Houston, who presided over implementing many of Page's proposed reforms, worked with Congressman Asbury Francis Lever on introducing a bill that became known upon passage as the Smith–Lever Act of 1914. This act established government subsidies for a demonstration farming program allowing farmers to voluntarily experiment with farming techniques agricultural experts had favored. Proponents of the Smith–Lever Act overcame many conservatives' objections by adding a provisions designed to bolster local control. Local agricultural colleges supervised agricultural extension agents charged with providing technical advice. Those agents were barred from operating without county governments' approval, which were also required to supply matching funds for the program. By 1924, three-quarters of the agriculture-oriented counties in the United States took part in the agricultural extension program.[60] Wilson also helped ensure passage of the Federal Farm Loan Act, which created twelve regional banks empowered to provide low-interest loans to farmers.[61]

The Philippines and Puerto Rico

Wilson supported the long-standing Democratic policy against owning colonies, and he worked for gradual autonomy and ultimate independence of the Philippines. Filipinos gained greater control over the Philippine Legislature. The House also passed a measure to grant the Philippines full independence, but Republicans strongly opposed this act and the Senate then blocked it. The Jones Act of 1916 committed the United States to the eventual independence of the Philippines; independence took place in 1946.[62] The Jones Act of 1917 upgraded the status of Puerto Rico. It created the Senate of Puerto Rico, established a bill of rights, and authorized the election of a Resident Commissioner (who the President had previously appointed) to a four-year term. The Resident Commissioner serves as a non-voting member of the U.S. House of Representatives. The act also granted Puerto Ricans U.S. citizenship and exempted Puerto Rican bonds from federal, state, and local taxes.[63]

Immigration policy

Immigration was a high priority topic in American politics during Wilson's presidency, but he paid very little attention to all that.[64] He opposed the restrictive immigration policies that many members of both parties favored. Wilson's progressivism encouraged his belief that immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe, though poor and illiterate, could assimilate into a homogeneous white middle class. He rejected discrimination against him. However, the so-called "hyphenated" Irish and German elements repulsed him because they were motivated to help the wartime needs of Ireland and Germany, not to the needs and values of the United States.[65] Very high rates of immigration suddenly ended in 1914, as European nations closed their borders. Emigration back to Europe also virtually ended.

Wilson vetoed the Immigration Act of 1917, but Congress overrode the veto. Its goal was to reduce immigration from Eastern and Southern Europe, by requiring literacy tests. It was the first U.S. law to restrict immigration from Europe, and it foreshadowed the more restrictive immigration laws of the 1920s.[66]

Home front during World War

With the American entrance into World War I in April 1917, Wilson became a war-time president. The War Industries Board, headed by Bernard Baruch, was established to set U.S. war manufacturing policies and goals. Future President Herbert Hoover led the Food Administration; the Federal Fuel Administration, run by Henry Garfield, introduced daylight saving time and rationed fuel supplies; William McAdoo was in charge of war bond efforts; Vance McCormick headed the War Trade Board. These men, known collectively as the "war cabinet", met weekly with Wilson at the White House.[67] Wilson established a large propaganda office, the Committee on Public Information, to encourage patriotism and fight defeatism and sedition.Because he was heavily focused on foreign policy during World War I, Wilson delegated a large degree of authority over the home front to his subordinates.[68]

The great majority of unions, including the AFL and the railroad brotherhoods, supported the war effort, and were rewarded for their efforts with high pay and access to Wilson. Strikes were rare. Unions saw enormous growth in membership and wages during the war, but there was no planning for postwar, and 1919 was marked by severe strikes and crises.[69] Wilson established the National War Labor Board (NWLB) to mediate wartime labor disputes, but it was slow to organize and the Labor Department provided mediation services in more disputes. Wilson's labor policies continued to stress mediation and agreement on all sides. When Smith & Wesson refused to assent to an NWLB ruling, the War Department seized control of the gun company and forced employees to return to work.[70]

The federal budget soared from $1 billion in fiscal year 1916 to $19 billion fiscal year 1919. The United States funded its participation in the war through a mix of increased taxes and war bonds. The War Revenue Act of 1917 and the Revenue Act of 1918 each raised taxes substantially. Treasury Secretary McAdoo authorized the issuing of low-interest war bonds and, to attract investors, made interest on the bonds tax-free. The bonds proved so popular among investors that many borrowed money in order to buy more bonds. The purchase of bonds, along with other war-time pressures, resulted in rising inflation. However, wages rose for laborers and profits rose for farmers and business owners do to the stimulative effect of government spending.[71] The United States also provided large loans to the Allied countries, helping to prevent the economic collapse of Britain and France. By the end of the war, the United States had become a creditor nation for the first time in its history.[72]

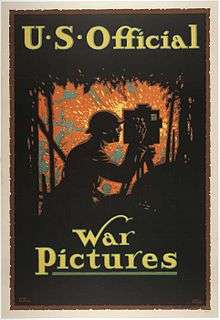

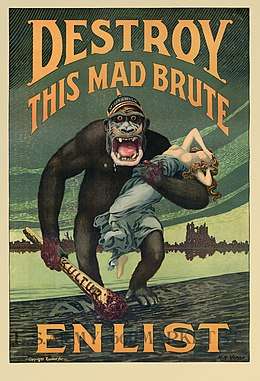

Propaganda

Wilson established the first modern propaganda office, the Committee on Public Information (CPI), headed by George Creel.[73][74] Creel set out to systematically reach every person in the United States multiple times with patriotic information about how the individual could contribute to the war effort. It also worked with the post office to censor seditious counter-propaganda. Creel set up divisions in his new agency to produce and distribute innumerable copies of pamphlets, newspaper releases, magazine advertisements, films, school campaigns, and the speeches of the Four Minute Men. CPI created colorful posters that appeared in every store window, catching the attention of the passersby for a few seconds.[75] Movie theaters were widely attended, and the CPI trained thousands of volunteer speakers to make patriotic appeals during the four-minute breaks needed to change reels. They also spoke at churches, lodges, fraternal organizations, labor unions, and even logging camps. Speeches were mostly in English, but ethnic groups were reached in their own languages.

Creel boasted that in 18 months his 75,000 volunteers delivered over 7.5 million four minute orations to over 300 million listeners, in a nation of 103 million people. The speakers attended training sessions through local universities, and were given pamphlets and speaking tips on a wide variety of topics, such as buying Liberty Bonds, registering for the draft, rationing food, recruiting unskilled workers for munitions jobs, and supporting Red Cross programs.[76] Historians were assigned to write pamphlets and in-depth histories of the causes of the European war.[77][78]

Disloyalty

To counter disloyalty to the war effort at home, Wilson pushed through Congress the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918 to suppress anti-British, pro-German, or anti-war statements."[79] While he welcomed socialists who supported the war, he pushed at the same time to arrest and deport foreign-born enemies.[80] Many recent immigrants, resident aliens without U.S. citizenship, who opposed America's participation in the war were deported to Soviet Russia or other nations under the powers granted in the Immigration Act of 1918.[80][81] Because of the lack of a national police force, the Wilson administration relied heavily on state and local police forces, as well as voluntary compliance, to enforce war-time laws.[82] Anarchists, communists, Industrial Workers of the World members, and other antiwar groups attempting to sabotage the war effort were targeted by the Department of Justice; many of their leaders were arrested for incitement to violence, espionage, or sedition.[80][81] Eugene Debs, the 1912 Socialist presidential candidate, was among the most prominent individuals jailed for sedition. In response to concerns over civil liberties, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), a private organization devoted to the defense of free speech, was founded in 1917.[83]

Prohibition

Prohibition developed as an unstoppable reform during the war, but Wilson played a minor role in its passage.[84] A combination of the temperance movement, hatred of everything German (including beer and saloons), and activism by churches and women led to ratification of an amendment to achieve Prohibition in the United States. A Constitutional amendment passed both houses in December 1917 by 2/3 votes. By January 16, 1919, the Eighteenth Amendment had been ratified by 36 of the 48 states it needed. On October 28, 1919, Congress passed enabling legislation, the Volstead Act, to enforce the Eighteenth Amendment. Wilson felt Prohibition was unenforceable, but his veto of the Volstead Act was overridden by Congress.[85] Prohibition began on January 16, 1920; the manufacture, importation, sale, and transport of alcohol were prohibited, except for limited cases such as religious purposes (as with sacramental wine).[86]

Women's suffrage

Wilson personally favored women's suffrage, but said it was a state matter. Opposition was too strong in the South.[87] A win for suffrage in New York state, combined with the increasingly prominent role women took in the war effort in factories and at home, convinced Wilson and many others to fully support women's suffrage.[88] In a January 1918 speech before the Congress, Wilson for the first time endorsed a national right to vote: "We have made partners of the women in this war....Shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right?"[89] The House quickly passed a constitutional amendment, but it stalled in the Senate.[90] Wilson continued to pressure senators to vote for the bill, and in June 1919 the Senate approved the amendment. The requisite number of states ratified the Nineteenth Amendment in August 1920.[91]

Demobilization and First Red Scare

Wilson's leadership in domestic policy in the aftermath of the war was complicated by his focus on the Treaty of Versailles, opposition from the Republican-controlled Congress, and, beginning late 1919, Wilson's illness.[92] A plan to form a commission for the purpose of demobilization of the war effort was abandoned due to the Republican control of the Senate, as Republicans could block the appointment of commission members. Instead, Wilson favored the prompt dismantling of wartime boards and regulatory agencies.[93] Though McAdoo and others favored extending government control of railroads under the United States Railroad Administration, Wilson signed the Esch–Cummins Act, which restored private control in 1920.[94] Demobilization was chaotic and violent; four million soldiers were sent home with little planning, little money, few benefits, and other vague promises. A wartime bubble in prices of farmland burst, leaving many farmers deeply in debt after they purchased new land. Major strikes in the steel, coal, and meatpacking industries disrupted the economy in 1919.[95] The country was also hit by the 1918 flu pandemic, which killed over 600,000 Americans in 1918 and 1919.[96] A massive agricultural price collapse was averted in 1919 in early 1920 through the efforts of Hoover's Food Administration, but prices dropped substantially in late 1920.[97] After the expiration of wartime contracts in 1920, the U.S. plunged into a severe recession,[98] and unemployment rose to 11.9%.[99]

Following the October Revolution in the Russian Empire, many in America feared the possibility of a Communist-inspired revolution in the United States. These fears were inflamed by the 1919 United States anarchist bombings, which were conducted by the anarchist Luigi Galleani and his followers.[100] Fears over left-wing subversion, combined with a patriotic national mood, led to the outbreak of the so-called "First Red Scare." Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer convinced Wilson to delay amnesty for those who had been convicted of war-time sedition, and he launched the Palmer Raids to suppress radical organizations.[101] Palmer's activities met resistance from the courts and from some senior officials in the Wilson administration, but Wilson, who was physically incapacitated by late 1919, did not move to stop the raids.[102] Palmer warned of a massive 1920 May Day uprising, but after the day passed by without incident, the Red Scare largely dissipated.[103]

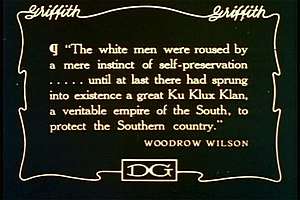

Civil rights

Segregation of government offices and discriminatory hiring practices had been started by President Theodore Roosevelt and continued by President Taft, but the Wilson administration escalated the practice.[104] Historian Kendrick Clements argues that "Wilson had none of the crude, vicious racism of James K. Vardaman or Benjamin R. Tillman, but he was insensitive to African-American feelings and aspirations."[105] In Wilson's first month in office, Postmaster General Albert S. Burleson brought up the issue of segregating workplaces in a cabinet meeting and urged the president to establish it across the government, in restrooms, cafeterias and work spaces.[106] Treasury Secretary William G. McAdoo also permitted lower-level officials to racially segregate employees in the workplaces of those departments. By the end of 1913 many departments, including the Navy, had workspaces segregated by screens, and restrooms, cafeterias were segregated, although no executive order had been issued.[106] During Wilson's term, the government also began requiring photographs of all applicants for federal jobs.[107]

Ross Kennedy writes that Wilson's support of segregation complied with predominant public opinion,[108] but his change in federal practices was protested in letters from both blacks and whites to the White House, mass meetings, newspaper campaigns and official statements by both black and white church groups.[106] The president's African-American supporters, who had crossed party lines to vote for him, were bitterly disappointed, and they and Northern leaders protested the changes.[106] Wilson defended his administration's segregation policy in a July 1913 letter responding to Oswald Garrison Villard, publisher of the New York Evening Post and founding member of the NAACP; Wilson suggested the segregation removed "friction" between the races.[106]

Partly in response to the demand for industrial labor, the Great Migration of African Americans out of the South began in 1917. This migration sparked race riots, including the East St. Louis riots of 1917. In response to these riots, Wilson asked Attorney General Thomas Watt Gregory if the federal government could intervene to "check these disgraceful outrages." However, on the advice of Gregory, Wilson did not involve the government in taking action against the riots.[109] Following the end of the war, another series of race riots occurred in Chicago, Omaha, and two dozen other major cities in the North.[110]

Wilson's War Department drafted hundreds of thousands of blacks into the army, giving them equal pay with whites, but in accord with military policy from the Civil War through the Second World War, kept them in all-black units with white officers, and kept the great majority out of combat.[111] When a delegation of blacks protested the discriminatory actions, Wilson told them "segregation is not a humiliation but a benefit, and ought to be so regarded by you gentlemen." In 1918, W. E. B. Du Bois—a leader of the NAACP who had campaigned for Wilson believing he was a "liberal southerner"—was offered an Army commission in charge of dealing with race relations; DuBois accepted, but he failed his Army physical and did not serve.[112][113] By 1916, Du Bois opposed Wilson, charging that his first term had seen "the worst attempt at Jim Crow legislation and discrimination in civil service that [blacks] had experienced since the Civil War."[113]

Foreign policy

Idealism

Wilson's foreign policy was based on an idealistic approach to liberal internationalism standing in sharp contrast to the realistic conservative nationalism of Taft, Roosevelt, and McKinley. Since 1900, the consensus of Democrats had, according to Arthur Link:

- consistently condemned militarism, imperialism, and interventionism in foreign policy. They instead advocated world involvement along liberal-internationalist lines. Wilson's appointment of William Jennings Bryan as Secretary of State indicated a new departure, for Bryan had long been the leading opponent of imperialism and militarism and a pioneer in the world peace movement.[114]

Bryan took the initiative in asking 40 countries with ambassadors in Washington to sign bilateral arbitration treaties. Any dispute of any kind with the United States would lead to a one-year cooling-off period, and submission to an international commission for arbitration. Thirty countries signed, but not Mexico and Colombia (which had grievances with Washington), nor Japan, Germany, Austria-Hungary or the Ottoman Empire. Some European diplomats signed the treaties, but considered them irrelevant.[115]

Diplomatic historian George C. Herring says that Wilson's idealism was genuine, but that it was structured by blind spots:

- Wilson's genuine and deeply felt aspirations to build a better world suffered from a certain culture-blindness. He lacked experience in diplomacy and hence an appreciation of its limits. He had not traveled widely outside the United States and knew little of other peoples and cultures beyond Britain, which he greatly admired. Especially in his first years in office, he had difficulty seeing that well-intended efforts to spread U.S. values might be viewed as interference at best, coercion at worst. His vision was further narrowed by the terrible burden of racism, common among the elite of his generation, which limited his capacity to understand and respect people of different colors. Above all, he was blinded by his certainty of America's goodness and destiny.[116]

Latin America

Wilson sought closer relations with Latin America, and he hoped to create a Pan-American organization to arbitrate international disputes. He also negotiated a treaty with Colombia that would have paid that country an indemnity for the U.S. role in the secession of Panama, but the Senate defeated this treaty.[117] However, Wilson frequently intervened in Latin American affairs, saying in 1913: "I am going to teach the South American republics to elect good men."[118] The Dominican Republic had been a de facto American protectorate since Roosevelt's presidency, but suffered from instability. In 1916, Wilson sent troops to occupy the island, and the U.S. soldiers would remain until 1924. In 1915, the U.S. intervened in Haiti after a revolt overthrew the Haitian government, beginning an occupation that would last until 1919. Wilson also authorized military interventions in Cuba, Panama, and Honduras. The 1914 Bryan–Chamorro Treaty converted Nicaragua into another de facto protectorate, and the U.S. stationed soldiers there throughout Wilson's presidency.[119]

The Panama Canal opened in 1914, fulfilling the long-term American goal of building a canal across Central America. The canal provided relatively swift passage between the Pacific Ocean with the Atlantic Ocean, presenting new economic opportunities to the U.S. and allowing the U.S. Navy to quickly navigate between the two oceans. In 1916, Wilson signed the Treaty of the Danish West Indies, in which the United States acquired the Danish West Indies for $2 million. After the purchase, the islands were renamed as the United States Virgin Islands.

Mexican Revolution

Wilson took office during the Mexican Revolution, which had begun in 1911 after liberals overthrew the military dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz. Shortly before Wilson took office, conservatives retook power through a coup led by Victoriano Huerta.[120] Wilson rejected the legitimacy of Huerta's "government of butchers" and demanded Mexico hold democratic elections. Wilson's unprecedented approach meant no recognition and doomed Huerta's prospects for establishing a stable government.[121] After Huerta arrested U.S. Navy personnel who had accidentally landed in a restricted zone near the northern port town of Tampico, Wilson dispatched the Navy to occupy the Mexican city of Veracruz. A strong backlash against the American intervention among Mexicans of all political affiliations convinced Wilson to abandon his plans to expand the U.S. military intervention, but the intervention nonetheless helped convince Huerta to flee from the country.[122] A group led by Venustiano Carranza established control over a significant proportion of Mexico, and Wilson recognized Carranza's government in October 1915.[123]

Carranza continued to face various opponents within Mexico, including Pancho Villa, whom Wilson had earlier described as "a sort of Robin Hood."[123] In early 1916, Pancho Villa raided an American town in New Mexico, killing or wounding dozens of Americans and causing an enormous nationwide American demand for his punishment. Wilson ordered General John J. Pershing and 4000 troops across the border to capture Villa. By April, Pershing's forces had broken up and dispersed Villas bands, but Villa remained on the loose and Pershing continued his pursuit deep into Mexico. Carranza then pivoted against the Americans and accused them of a punitive invasion; a confrontation with a mob in Parral on April 12 resulted in two dead Americans and six wounded, plus hundreds of Mexican casualties. Further incidents led to the brink of war by late June, when Wilson demanded an immediate release of American soldiers held prisoner. The prisoners were released, tensions subsided, and bilateral negotiations began under the auspices of the Mexican-American Joint High Commission. Eager to withdraw from Mexico due to World War I, Wilson ordered Pershing to withdraw, and the last American soldiers left in February 1917. Biographer According to historian Arthur Link, Carranza's successful handling of the American intervention in Mexico left the country free to develop its revolution without American pressure.[124] The incident also made Pershing a national figure and led to Wilson choosing him to command the American forces in Europe in 1918. It also gave the American army some needed experience in dealing with training, planning and logistics.[125]

Neutrality in World War I

World War I broke out in July 1914, pitting Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria) against the Allied Powers (Great Britain, France, Russia, and several other countries). The war fell into a long stalemate after the German advance was halted in September 1914 at the First Battle of the Marne.[126] From 1914 until early 1917, Wilson's primary foreign policy objective was to keep the United States out of the war in Europe.[127] Wilson insisted that all government actions be neutral, and that the belligerents must respect that neutrality according to the norms of international law. After the war began, Wilson told the Senate that the United States, "must be impartial in thought as well as in action, must put a curb upon our sentiments as well as upon every transaction that might be construed as a preference of one party to the struggle before another." He was ambiguous whether he meant the United States as a nation or meant all Americans as individuals.[128] Though Wilson was determined to keep the United States out of the war, and he thought that the causes of the war were complex, he personally believed that the U.S. shared more values with the Allies than the Central Powers.[129]

Wilson and House sought to position the United States as a mediator in the conflict, but European leaders rejected Houses's offers to help end the conflict.[130] At the urging of Bryan, Wilson also discouraged American companies from extending loans to belligerents. The policy hurt the Allies more than the Central Powers, since the Allies were more dependent on American goods. The administration relaxed the policy of discouraging loans in October 1914 and then ended it in October 1915 due to fears about the policy's effect on the American economy.[131] The United States sought to trade with both the Allied Powers and the Central Powers, but the British attempted to imposed a Blockade of Germany, and, after a period of negotiations, Wilson essentially assented to the British blockade. The U.S. had relatively little direct trade with the Central Powers, and Wilson was unwilling to wage war against Britain over trade issues.[132] The British also made their blockade more acceptable to American leaders by buying, rather than seizing without compensation, intercepted goods.[133] However, many Germans viewed American trade with the Allies as decidedly unneutral.[132]

Growing tensions

In response to the British blockade of the Central Powers, the Germans launched a submarine campaign against merchant vessels in the seas surrounding the British Isles. Wilson strongly protested the policy, which had a much stronger affect on American trade than the British blockade.[134] In the March 1915, Thrasher Incident, the commercial British steamship Falaba was sunk by a German submarine with the loss of 111 lives, including one American.[135] In the spring of 1915 a German bomb struck an American ship, the Cushing and a German submarine torpedoed an American tanker, the Gulflight. Wilson took the view, based on some reasonable evidence, that both incidents were accidental, and that a settlement of claims could be postponed to the end of the war.[136] A German submarine torpedoed and sank the British ocean liner RMS Lusitania in May 1915; over a thousand perished, including many Americans.[137] Wilson did not call for war; instead he said, "There is such a thing as a man being too proud to fight. There is such a thing as a nation being so right that it does not need to convince others by force that it is right". He realized he had chosen the wrong words when critics lashed out at his rhetoric.[138] Wilson sent a protest to Germany which demanded that the German government "take immediate steps to prevent the recurrence" of incidents like the sinking of the Lusitania. In response, Bryan, who believed that Wilson had placed the defense of American trade rights above neutrality, resigned from the cabinet.[139]

The White Star liner the SS Arabic was torpedoed in August 1915, with two American casualties. The U.S. threatened a diplomatic break unless Germany repudiated the action. The Germans agreed to warn unarmed merchant ships before attacking them.[140] In March 1916, the SS Sussex, an unarmed ferry under the French flag, was torpedoed in the English Channel and four Americans were counted among the dead; the Germans had flouted the post-Lusitania exchanges. The president demanded the Germans reject their submarine tactics. Wilson drew praise when he succeeded in wringing from Germany a pledge to constrain submarine warfare to the rules of cruiser warfare. This was a clear departure from existing practices—a diplomatic concession from which Germany could only more brazenly withdraw.[141] In January 1917, the Germans initiated a new policy of unrestricted submarine warfare against ships in the seas around the British Isles. German leaders knew that the policy would likely provoke U.S. entrance into the war, but they hoped to defeat the Allied Powers before the U.S. could fully mobilize.[142]

Preparedness

Military "preparedness," or building up the small army and navy—became a major dynamic of public opinion.[143][144] Theodore Roosevelt and General Leonard Wood took the lead, attacking Wilson for reliance on weakness instead of strength in dealing with the World War. New, well-funded organizations sprang up to appeal to the grassroots, including the American Defense Society (ADS) and the National Security League, both of which favored entering the war on the side of the Allies.[145][146] Interventionists, led by Theodore Roosevelt, wanted war with Germany and attacked Wilson's refusal to build up the U.S. Army in anticipation of war.[147] Wilson resistance to preparedness was partly due to the powerful anti-war element of the Democratic Party, which was led by Bryan. Anti-war sentiment was strong among many groups inside and outside of the party, including women,[148] Protestant churches,[149] labor unions,[150] and Southern Democrats like Claude Kitchin, chairman of the powerful House Ways and Means Committee. Biographer John Morton Blum says:

- Wilson's long silence about preparedness had permitted such a spread and such a hardening of antipreparedness attitudes within his party and across the nation that when he came in at late last to his task, neither Congress to the country was amenable to much persuasion.[151]

After the sinking of the Lusitania and the resignation of Bryan, Wilson publicly committed himself to preparedness and began to build up the army and the navy.[133] Wilson was constrained by America's traditional commitment to military nonintervention. Wilson believed that a massive military mobilization could only take place after a declaration of war, even though that meant a long delay in sending troops to Europe. Many Democrats felt that no American soldiers would be needed, only American money and munitions.[152] Wilson had more success in his request for a dramatic expansion of the Navy. Congress passed a Naval Expansion Act in 1916 that encapsulated the planning by the Navy's professional officers to build a fleet of top-rank status, but it would take several years to become operational.[153]

World War I

Entering the war

In early 1917, German ambassador Johann von Bernstorf informed Secretary of State Lansing of Germany's commitment to unrestricted submarine warfare.[154] In late February, the U.S. public learned of the Zimmermann Telegram, a secret diplomatic communication in which Germany sought to convince Mexico to join it in a war against the United States.[155] Wilson's reaction after consulting the cabinet and the Congress was a minimal one—that diplomatic relations with the Germans be brought to a halt. The president said, "We are the sincere friends of the German people and earnestly desire to remain at peace with them. We shall not believe they are hostile to us unless or until we are obliged to believe it".[156] After a series of attacks on American ships, Wilson held a cabinet meeting on March 20; all cabinet members agreed that the time had come for the United States to enter the war. Wilson called Congress into a special session, which would begin on April 2.[157]

March 1917 also brought the first of two revolutions in Russia, which impacted the strategic role of the U.S. in the war. The overthrow of the imperial government removed a serious barrier to America's entry into the European conflict, while the second revolution in November relieved the Germans of a major threat on their eastern front, and allowed them to dedicate more troops to the Western front, thus making U.S. forces central to Allied success in battles of 1918. Wilson initially rebuffed pleas from the Allies to dedicate military resources to an intervention in Russia against the Bolsheviks, based partially on his experience from attempted intervention in Mexico; nevertheless he ultimately was convinced of the potential benefit and agreed to dispatch a limited force to assist the Allies on the eastern front.[158]

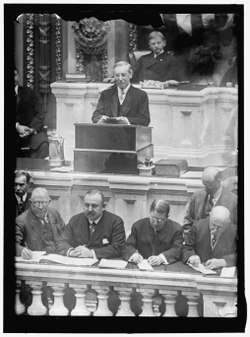

Wilson addressed Congress on April 2, calling for a declaration of war against Germany. He argued that the Germans were engaged in "nothing less than war against the government and people of the United States." He asked for a military draft to raise the army, increased taxes to pay for military expenses, loans to Allied governments, and increased industrial and agricultural production.[159] The declaration of war by the United States against Germany passed Congress by strong bipartisan majorities on April 4, 1917, with opposition from ethnic German strongholds and remote rural areas in the South. The United States would also later declare war against Austria-Hungary in December 1917. The U.S. did not sign a formal alliance with Britain or France but operated as an "associated" power—an informal ally with military cooperation through the Supreme War Council in London.[160]

The U.S. raised a massive army through conscription and Wilson gave command to General John J. Pershing. Pershing would have complete authority as to tactics, strategy, and some diplomacy.[161] Edward House became the president's main channel of communication with the British government, and William Wiseman, a British naval attaché, was House's principal contact in England. Their personal relationship succeeded in serving the powers well, by overcoming strained relations in order to achieve essential understandings between the two governments. House also became the U.S. representative on the Allies' Supreme War Council.[162]

The Fourteen Points

Wilson sought the establishment of "an organized common peace" that would help prevent future conflicts. In this goal, he was opposed not just by the Central Powers, but also the other Allied Powers, who, to various degrees, sought to win concessions and oppose a punitive peace agreement on the Central Powers.[163] He initiated a secret series of studies named The Inquiry, primarily focused on Europe, and carried out by a group in New York which included geographers, historians and political scientists; the group was directed by Col. House.[164] The studies culminated in a speech by Wilson to Congress on January 8, 1918, wherein he articulated America's long term war objectives. It was the clearest expression of intention made by any of the belligerent nations. The speech, known as the Fourteen Points, was authored mainly by Walter Lippmann and projected Wilson's progressive domestic policies into the international arena. The first six dealt with diplomacy, freedom of the seas and settlement of colonial claims. Then territorial issues were addressed and the final point, the establishment of an association of nations to guarantee the independence and territorial integrity of all nations—a League of Nations. The address was translated into many languages for global dissemination.[165]

Aside from post-war considerations, Wilson's Fourteen Points were motivated by several factors. Unlike some of the other Allied leaders, Wilson did not call for a break-up of the Ottoman Empire or the Austro-Hungarian Empire, nor did he call for self-determination throughout Europe. In offering a non-punitive peace to these nations as well as Germany, Wilson hoped to quickly began negotiations to end the war. Wilson's liberal pronouncements were also targeted at pacifistic and war-weary elements within the Allied countries, including the United States. Additionally, Wilson hoped to woo the Russians back into the war, although he failed in this goal.[166]

Course of the war

With the U.S. entrance into the war, Wilson and Secretary of War Baker launched an expansion of the army, with the goal of creating a 300,000-member Regular Army, a 440,000-member National Guard, and a 500,000-member conscripted force known as the "National Army." Despite some resistance to conscription and the commitment of American soldiers abroad, large majorities of both houses of Congress voted in favor of the Selective Service Act of 1917. Seeking to avoid the draft riots of the Civil War, the bill established local draft boards that were charged with determining who should be drafted. By the end of the war, nearly 3 million men would be drafted.[167] The Navy also saw tremendous expansion, and, at the urging of Admiral William Sims, focused on building anti-submarine vessels. Allied shipping losses dropped substantially due to U.S. contributions and a new emphasis on the convoy system.[168]

The American Expeditionary Forces first arrived in France in mid-1917.[169] Wilson and Pershing rejected the British and French proposal that American soldiers integrate into existing Allied units, giving the United States more freedom of action but requiring for the creation of new organizations and supply chains.[170] There were only 175,000 American soldiers in Europe at the end of 1917, but by mid-1918 10,000 Americans arrived in Europe per day. Russia exited the war after the March 1918 signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, allowing Germany to shift soldiers from the Eastern Front of the war. The Germans launched a Spring Offensive against the Allies that inflicted heavy casualties but failed to break the Allied line. Beginning in August, the Allies launched the Hundred Days Offensive that pushed back the exhausted German army.[171]

By the end of September, the German leadership no longer believed it could win the war. Recognizing that Wilson would be more likely to accept a peace deal from a democratic government, Kaiser Wilhelm II appointed a new government led by Prince Maximilian of Baden; Baden immediately sought an armistice with Wilson.[172] In the exchange of notes, German and American leaders agreed to incorporate the Fourteen Points in the armistice; House then procured agreement from France and Britain, but only after threatening to conclude a unilateral armistice without them. Wilson ignored Pershing's plea to drop the armistice and instead demand an unconditional surrender by Germany.[173] The Germans signed the Armistice of 11 November 1918, bringing an end to the fighting. Austria-Hungary had signed the Armistice of Villa Giusti eight days earlier, while the Ottoman Empire had signed the Armistice of Mudros in October.

Aftermath of World War I

Paris Peace Conference

After the signing of the armistice, Wilson traveled to Europe to attend the Paris Peace Conference, thereby becoming the first U.S. president to travel to Europe while in office.[174] Save for a two-week return to the United States, Wilson remained in Europe for six months, where he focused on a peace treaty to formally end the war. The defeated Central Powers had not been invited to the conference, and anxiously awaited their fate. Wilson, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, and Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando made up the "Big Four," the Allied leaders with the most influence at the Paris Peace Conference. Though Wilson continued to advocate his idealistic Fourteen Points, many of the other allies desired revenge. Clemenceau especially sought onerous terms for Germany, while Lloyd George supported some of Wilson's ideas but feared public backlash if the treaty proved too favorable to the Central Powers.[175]

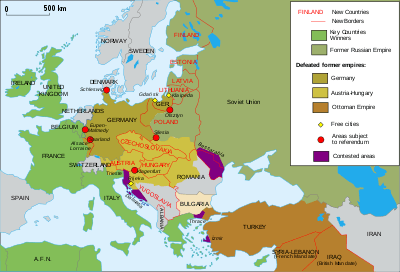

In pursuit of his League of Nations, Wilson conceded several points to the other powers present at the conference. France pressed for the dismemberment of Germany and the payment of a huge sum in war reparations. Wilson resisted these ideas, but Germany was still required to pay war reparations and subjected to military occupation in the Rhineland, and a clause in the treaty specifically named Germany as responsible for the war. Wilson also agreed to the creation of mandates in former German and Ottoman territories, allowing the European powers and Japan to establish de facto colonies in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia. The Japanese acquisition of German interests in the Shandong Peninsula of China proved especially unpopular, as it undercut Wilson's promise of self-government. However, Wilson won the creation of several new states in Central Europe and the Balkans, including Poland, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Ottoman Empire were partitioned.[176] Wilson refused to concede to Italy's demands for territory on the Adriatic coast, and a dispute between Yugoslavia and Italy would not be settled until the signing of the 1920 Treaty of Rapallo.[177] Japan proposed that the conference endorse a racial equality clause. Wilson was indifferent to the issue, but acceded to strong opposition from Australia and Britain.[178]

The Covenant of the League of Nations was incorporated into the conference's Treaty of Versailles, which ended the war with Germany.[179] Wilson himself presided over the committee that drafted the covenant, which bound members to oppose "external aggression" and to agree to peacefully settle disputes through organizations like the Permanent Court of International Justice.[180] During the conference, Taft cabled to Wilson three proposed amendments to the League covenant which he thought would considerably increase its acceptability to the Europeans—the right of withdrawal from the League, the exemption of domestic issues from thet League, and the inviolability of the Monroe Doctrine. Wilson very reluctantly accepted these amendments. In addition to the Treaty of Versailles, the Allies also wrote treaties with Austria (the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye), Hungary (the Treaty of Trianon), the Ottoman Empire (the Treaty of Sèvres), and Bulgaria (the Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine), all of which incorporated the League of Nations charter.[181]

The conference finished negotiations in May 1919, at which point German leaders viewed the treaty for the first time. Some German leaders favored repudiating the treaty, but Germany signed the treaty on June 28, 1919.[182] For his peace-making efforts, Wilson was awarded the 1919 Nobel Peace Prize.[183] However, the defeated Central Powers protested the harsh terms of the treaty, while several colonial representatives pointed out the hypocrisy of a treaty that established new nations in Europe but allowed continued colonialism in Asia and Africa. Wilson also faced an uncertain domestic battle to ratify the treaty, as Republicans largely opposed it.[184]

Treaty ratification debate

The chances were less than favorable for ratification of the treaty by a two-thirds vote of the Senate, in which Republicans held a narrow majority.[185] Public opinion was mixed, with intense opposition from most Republicans, Germans, and Irish Catholic Democrats. In numerous meetings with Senators, Wilson discovered opposition had hardened. Despite his weakened physical condition following the Paris Peace Conference, Wilson decided to barnstorm the Western states, scheduling 29 major speeches and many short ones to rally support.[186] Wilson suffered a series of debilitating strokes and had to cut short his trip on in September 1919. He became an invalid in the White House, closely monitored by his wife, who insulated him from negative news and downplayed for him the gravity of his condition.[187]

Senator Henry Cabot Lodge led the opposition to the treaty; he despised Wilson and hoped to humiliate him in the ratification battle. Republicans were outraged by Wilson's failure to discuss the war or its aftermath with them. An intensely partisan battle developed in the Senate, as Republicans opposed the treaty and Democrats largely supported it. The debate over the treaty centered around a debate over the American role in the world community in the post-war era, and Senators fell into three main groups. Most Democrats favored the treaty.[185] Fourteen Senators, mostly Republicans, become known as the "irreconcilables," as they completely opposed U.S. entrance into the League of Nations. Some of these irreconcilables, such as George W. Norris, opposed the treaty for its failure to support decolonization and disarmament. Other irreconcilables, such as Hiram Johnson, feared surrendering American freedom of action to an international organization. Most sought the removal of Article X the League covenant, which purported to bind nations to defend each other against aggression.[188] The remaining group of Senators, known as "reservationists," accepted the idea of the league, but sought varying degrees of change to the League to ensure the protection of U.S. sovereignty.[188] Former President Taft and former Secretary of State Elihu Root both favored ratification of the treaty with some modifications, and their public support for the treaty gave Wilson some chance of winning significant Republican support for ratification.[185]

Despite the difficulty of winning ratification, Wilson consistently refused to accede to reservations, partly due to concerns about having to re-open negotiations with the other powers if reservations were added.[189] In mid-November 1919, Lodge and his Republicans formed a coalition with the pro-treaty Democrats, and were close to a two-thirds majority for a treaty with reservations, but the seriously indisposed Wilson rejected this compromise and enough Democrats followed his lead to defeat ratification. Cooper and Bailey suggest that Wilson's stroke in September had debilitated him from negotiating effectively with Lodge.[190] U.S. involvement in World War I would not formally end until the passage of the Knox–Porter Resolution in 1921.

Intervention in Russia

After Russia left World War I following the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, the Allies sent troops there to prevent a German or Bolshevik takeover of allied-provided weapons, munitions and other supplies previously shipped as aid to the pre-revolutionary government.[191] Wilson loathed the Bolsheviks, who he believed did not represent the Russian people, but he feared that foreign intervention would only strengthen Bolshevik rule. Britain and France pressured him to intervene in order to potentially re-open a second front against Germany, and Wilson acceded to this pressure in the hope that it would help him in post-war negotiations and check Japanese influence in Siberia.[192] The U.S. sent armed forces to assist the withdrawal of Czechoslovak Legions along the Trans-Siberian Railway, and to hold key port cities at Arkhangelsk and Vladivostok. Though specifically instructed not to engage the Bolsheviks, the U.S. forces engaged in several armed conflicts against forces of the new Russian government. Revolutionaries in Russia resented the United States intrusion. Robert Maddox wrote, "The immediate effect of the intervention was to prolong a bloody civil war, thereby costing thousands of additional lives and wreaking enormous destruction on an already battered society."[193]

Other issues

In 1919, Wilson guided American foreign policy to "acquiesce" in the Balfour Declaration without supporting Zionism in an official way. Wilson expressed sympathy for the plight of Jews, especially in Poland and France.[194]

In May 1920, Wilson sent a long-deferred proposal to Congress to have the U.S. accept a mandate from the League of Nations to take over Armenia.[195] Bailey notes this was opposed by American public opinion,[196] while Richard G. Hovannisian states that Wilson "made all the wrong arguments" for the mandate and focused less on the immediate policy than on how history would judge his actions: "[he] wished to place it clearly on the record that the abandonment of Armenia was not his doing."[197] The resolution won the votes of only 23 senators.

List of international trips

Wilson made two international trips during his presidency.[198] He was the first sitting president to travel to Europe. He spent nearly seven months in Europe after World War I (interrupted by a brief 9-day return stateside).

| Dates | Country | Locations | Details | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | December 14–25, 1918 | Paris, Chaumont |

Attended preliminary discussions prior to the Paris Peace Conference; promoted his Fourteen Points principles for world peace. Departed the U.S. December 4. | |

| December 26–31, 1918 | London, Carlisle, Manchester |

Met with Prime Minister David Lloyd George and King George V. | ||

| December 31, 1918 – January 1, 1919 | Paris | Stopover en route to Italy. | ||

| January 1–6, 1919 | Rome, Genoa, Milan, Turin |

Met with King Victor Emmanuel III and Prime Minister Vittorio Orlando. | ||

| January 4, 1919 | Rome | Audience with Pope Benedict XV. | ||

| January 7 – February 14, 1919 | Paris | Attended Paris Peace Conference. Returned to the U.S. February 24. | ||

| 2 | March 14 – June 18, 1919 | Paris | Attended Paris Peace Conference. Departed the U.S. March 5. | |

| June 18–19, 1919 | Brussels, Charleroi, Malines, Louvain |

Met with King Albert I. Addressed Parliament. | ||

| June 20–28, 1919 | Paris | Attended Paris Peace Conference. Returned to the U.S. July 8. |

Incapacity, 1919–1920

In September 1919, while on a public speaking tour in support of the ratification of the Treaty of Versailles, Wilson collapsed and never fully recovered.[199] On October 2, 1919, Wilson suffered a serious stroke, leaving him paralyzed on his left side, and with only partial vision in the right eye.[200] He was confined to bed for weeks and sequestered from everyone except his wife and physician, Dr. Cary Grayson.[199] Doctor Bert E. Park, a neurosurgeon who examined Wilson's medical records after his death, writes that Wilson's illness affected his personality in various ways, making him prone to "disorders of emotion, impaired impulse control, and defective judgment."[201] In the months after the stroke, Wilson was insulated by his wife, who selected matters for his attention and delegated others to his cabinet. Wilson temporarily resumed a perfunctory attendance at cabinet meetings.[202] His wife and aide Joe Tumulty were said to have helped a journalist, Louis Seibold, present a false account of an interview with the president.[203] Despite his health problems, Wilson only rarely considered resigning, and he continued to advocate ratification of the Treaty of Versailles.[204]

By February 1920, the president's true condition was publicly known. Many expressed qualms about Wilson's fitness for the presidency at a time when the League fight was reaching a climax, and domestic issues such as strikes, unemployment, inflation and the threat of Communism were ablaze. No one close to Wilson, including his wife, his physician, or personal assistant, was willing to take responsibility to certify, as required by the Constitution, his "inability to discharge the powers and duties of the said office".[205] Though some members of Congress encouraged Vice President Marshall to assert his claim to the presidency, Marshall never attempted to replace Wilson.[23] Wilson's lengthy period of incapacity while serving as president was nearly unprecedented; of the previous presidents, only James Garfield had been in a similar situation, but Garfield retained greater control of his mental faculties and faced relatively few pressing issues.[206]

Elections during the Wilson presidency

Midterm elections of 1914

In Wilson's first mid-term elections, Republicans picked up sixty seats in the House, but failed to re-take the chamber. In the first Senate elections since the passage of the Seventeenth Amendment, Democrats retained their Senate majority. Roosevelt's Bull Moose Party, which had won a handful of Congressional seats in the 1912 election, fared poorly, while conservative Republicans also defeated several progressive Republicans. The continuing Democratic control of Congress pleased Wilson, and he publicly argued that the election represented a mandate for continued progressive reforms.[207] In the ensuing 64th Congress, Wilson and his allies passed several more laws, though none were as impactful as the major domestic initiatives that had been passed during Wilson's first two years in office.[208]

Presidential election of 1916

Wilson, renominated without opposition, employed his campaign slogan "He kept us out of war", though he never promised unequivocally to stay out of the war. In his acceptance speech on September 2, 1916, Wilson pointedly warned Germany that submarine warfare resulting in American deaths would not be tolerated, saying "The nation that violates these essential rights must expect to be checked and called to account by direct challenge and resistance. It at once makes the quarrel in part our own."[209]

Vance C. McCormick, a leading progressive, became chairman of the party, and Ambassador Henry Morgenthau was recalled from Turkey to manage campaign finances.[210] "Colonel" House played an important role in the campaign. "He planned its structure; set its tone; helped guide its finance; chose speakers, tactics, and strategy; and, not least, handled the campaign's greatest asset and greatest potential liability: its brilliant but temperamental candidate."[211]

As the party platform was drafted, Senator Owen of Oklahoma urged Wilson to take ideas from the Progressive Party platform of 1912 "as a means of attaching to our party progressive Republicans who are in sympathy with us in so large a degree." At Wilson's request, Owen highlighted federal legislation to promote workers' health and safety, prohibit child labor, provide unemployment compensation and establish minimum wages and maximum hours. Wilson, in turn, included in his draft platform a plank that called for all work performed by and for the federal government to provide a minimum wage, an eight-hour day and six-day workweek, health and safety measures, the prohibition of child labour, and (his own additions) safeguards for female workers and a retirement program.[212]

The 1916 Republican National Convention nominated Supreme Court Justice Charles Evans Hughes for president. A former governor of New York, Hughes sought to reunify the progressive and conservative wings of the party. Republicans campaigned against Wilson's New Freedom policies, especially tariff reduction, the implementation of higher income taxes, and the Adamson Act, which they derided as "class legislation."[213] Republicans also attacked Wilson's foreign policy on various grounds, but domestic affairs generally dominated the campaign. As election day neared, both sides saw victory as a strong possibility.[214]