Presidency of William Howard Taft

| Presidency of William Howard Taft | |

|---|---|

| |

| In office | |

| March 4, 1909 – March 4, 1913 | |

| Preceded by | T. Roosevelt presidency |

| Succeeded by | Wilson presidency |

| Seat | White House, Washington, D.C. |

| Political party | Republican |

The presidency of William Howard Taft began on March 4, 1909, at noon Eastern Standard Time, when William Howard Taft was inaugurated as President of the United States, and ended on March 4, 1913. Taft, a Republican, was the 27th United States president. The protégé and chosen successor of incumbent President Theodore Roosevelt, he took office after easily defeating Democrat William Jennings Bryan in the 1908 presidential election. His presidency ended with his defeat in the 1912 election by Democrat Woodrow Wilson.

In foreign affairs, Taft focused on East Asia and repeatedly intervened to prop up or remove Latin American governments. Taft sought to uphold the Monroe Doctrine and avoid U.S. entanglement in European affairs. His administration followed a policy of Dollar Diplomacy, hoping to use U.S. investment to enhance U.S. influence in Latin America. The defense of the Panama Canal, which was completed in 1914, was central to Taft's foreign policy. The Taft administration also sought reductions to trade tariffs, then a major source of governmental income, but the Payne–Aldrich Tariff Act of 1909 was heavily influenced by special interests. Taft made six appointments to the United States Supreme Court, more than all but two other presidents.

His administration was filled with conflict between the conservative wing of the Republican Party, with which Taft often sympathized, and the progressive wing, toward which Roosevelt moved more and more during Taft's presidency. Controversies over conservation and over antitrust cases filed by the Taft administration served to further separate the two men. Roosevelt challenged Taft at the 1912 Republican National Convention, but Taft was able to use his control of the party machinery to narrowly win his party's nomination. After the convention, Roosevelt left the party, formed the Progressive Party, and ran for president in the 1912 election under its banner. This split among Republicans all but doomed Taft's chances for re-election, giving Democrats, in the person of Woodrow Wilson, control of the White House for the first time in sixteen years. Historians generally consider Taft to have been an average president.

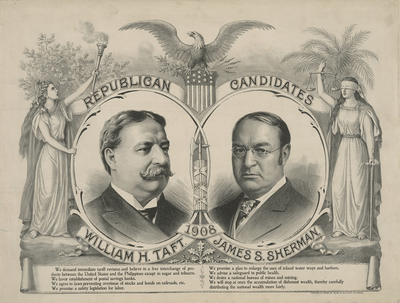

Election of 1908

As the 1908 presidential election approached, President Roosevelt, who had announced after his 1904 victory that he would not run for re-election considered Secretary of War Taft was his logical successor, although Taft was initially reluctant to run.[1] He would have preferred being appointed U.S. Supreme Court chief justice.[2] Roosevelt used his control of the party machinery to aid his heir apparent,[1] and political appointees were required to support Taft or remain silent.[3] A number of Republican politicians, such as Treasury Secretary George Cortelyou, tested the waters for a run but chose to stay out. New York Governor Charles Evans Hughes ran, but when he made a major policy speech, Roosevelt the same day sent a special message to Congress warning in strong terms against corporate corruption. The resulting coverage of the presidential message relegated Hughes to the back pages.[4]

Assistant Postmaster General Frank H. Hitchcock resigned from his office in February 1908 to lead the Taft campaign.[5] In April, Taft made a speaking tour, traveling as far west as Omaha before being recalled to go to Panama and straighten out a contested election. At the 1908 Republican National Convention in Chicago in June, there was no serious opposition to him, and Taft gained a first-ballot victory. Yet Taft did not have things his own way: he had hoped his running mate would be a midwestern progressive like Iowa Senator Jonathan Dolliver, but instead the convention named Congressman James S. Sherman of New York, a conservative. Taft resigned as Secretary of War on June 30 to devote himself full-time to the campaign.[6][7]

Taft began the campaign on the wrong foot, fueling the arguments of those who said he was not his own man by traveling to Roosevelt's home at Sagamore Hill for advice on his acceptance speech, saying that he needed "the President's judgment and criticism".[8] Taft supported most of Roosevelt's policies. He argued that labor had a right to organize, but not boycott, and that corporations and the wealthy must also obey the law. Taft attributed blame for the recent recession, the Panic of 1907, to stock speculation and other abuses, and felt some reform of the currency (the U.S. was on the gold standard) was needed to allow flexibility in the government's response to poor economic times. He also spoke out in favor of tariff reforms (reductions) and of strengthening the Sherman Antitrust Act.

Taft's opponent in the general election was William Jennings Bryan, the Democratic nominee for the third time in four presidential elections. He campaigned on a progressive platform attacking "government by privilege",[9] and portraying Republicans as beholden to powerful corporate interests and to the wealthy. His campaign slogan was "Shall the People Rule?"[10] As many of Roosevelt's reforms stemmed from his proposals, the Democrat argued that he was the true heir to Roosevelt's mantle. Corporate contributions to federal political campaigns had been outlawed by the 1907 Tillman Act, and Bryan proposed that contributions by officers and directors of corporations be similarly banned, or at least disclosed when made. Taft was only willing to see the contributions disclosed after the election, and tried to ensure that officers and directors of corporations litigating with the government were not among his contributors.[11]

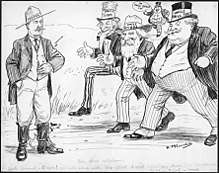

During the fall campaign Roosevelt showered Taft, a sluggish campaigner by nature,[2] with advice, and infused energy into his campaign, fearing that the electorate would not appreciate Taft's qualities, and that Bryan would win. Consequently, accusations abounded that the president was in effect running Taft's campaign.[12] His larger-than-life presence in the campaign also caught the attention of journalists and humorists who bombarded the public with jokes about Taft being nothing but a Roosevelt stand-in; one suggested that "TAFT" stood for "Take Advice From Theodore".[2][13]

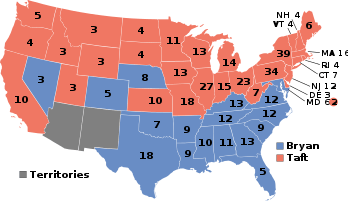

In the end, Taft defeated Bryan by 321 electoral votes to 162,[14] carrying all but three states outside the Democratic Solid South. He also won the popular vote by a comfortable margin, receiving 7,675,320 votes (51.6 percent) to Bryan's 6,412,294 (43.1 percent); Socialist Party candidate Eugene V. Debs won 420,793 votes (2.8 percent).[2]

Nellie Taft said regarding the campaign, "There was nothing to criticize, except his not knowing or caring about the way the game of politics is played."[15] Longtime White House usher Ike Hoover recalled that Taft came often to see Roosevelt during the campaign, but seldom between the election and Inauguration Day, March 4, 1909.[16] While president-elect Taft travelled to Panama (January 29 – February 7, 1909), where he inspected construction of Panama Canal and met with President José Domingo de Obaldía.[17]

Inauguration

Taft was sworn in as president on March 4, 1909. Due to a winter storm that coated Washington with ice, Taft was inaugurated within the Senate Chamber rather than outside the Capitol as is customary. The new president stated in his inaugural address that he had been honored to have been "one of the advisers of my distinguished predecessor" and to have had a part "in the reforms he has initiated. I should be untrue to myself, to my promises, and to the declarations of the party platform on which I was elected if I did not make the maintenance and enforcement of those reforms a most important feature of my administration".[18] He pledged to make those reforms long-lasting, ensuring that honest businessmen did not suffer uncertainty through change of policy. He spoke of the need for reduction of the 1897 Dingley Tariff, for antitrust reform, and for continued advancement of the Philippines toward full self-government.[19] Roosevelt left office with regret that his tenure in the position he enjoyed so much was over and, to keep out of Taft's way, arranged for a year-long hunting trip to Africa.[20]

Administration

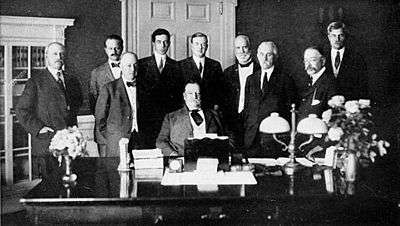

Cabinet

| The Taft Cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | William Howard Taft | 1909–1913 |

| Vice President | James S. Sherman | 1909–1912 |

| none | 1912–1913 | |

| Secretary of State | Philander C. Knox | 1909–1913 |

| Secretary of Treasury | Franklin MacVeagh | 1909–1913 |

| Secretary of War | Jacob M. Dickinson | 1909–1911 |

| Henry L. Stimson | 1911–1913 | |

| Attorney General | George W. Wickersham | 1909–1913 |

| Postmaster General | Frank H. Hitchcock | 1909–1913 |

| Secretary of the Navy | George von L. Meyer | 1909–1913 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Richard A. Ballinger | 1909–1911 |

| Walter L. Fisher | 1911–1913 | |

| Secretary of Agriculture | James Wilson | 1909–1913 |

| Secretary of Commerce & Labor | Charles Nagel | 1909–1913 |

Soon after the Republican convention, Taft and Roosevelt had discussed which cabinet officers would stay on. Taft kept only Agriculture Secretary James Wilson and Postmaster General George von Lengerke Meyer (who was shifted to the Navy Department). Taft also asked Secretary of State Elihu Root to remain in his position, but Root declined and instead recommended former Attorney General Philander C. Knox for the position. Others appointed to the Taft cabinet include Secretary of the Interior Richard A. Ballinger and Secretary of the Treasury Franklin MacVeagh.[21][22]

Vice Presidency

James S. Sherman had been added to the 1908 Republican ticket as a means to appease the conservative wing of the GOP, which viewed Taft as a progressive. As Taft moved to the right during his presidency, he became an important ally. Nominated for a second term at the 1912 Republican National Convention, he became ill during the campaign and died on October 30, 1912, just prior to the election.[23] As the Constitution then lacked a mechanism for choosing an intra-term replacement (prior to ratification of the Twenty-fifth Amendment in 1967), the vice presidency remained vacant for the final 125 days of Taft's presidency. During that time Secretary of State Philander C. Knox was next in line to the presidency, per the Presidential Succession Act of 1886.

Press corps

Taft did not enjoy the easy relationship with the press that Roosevelt had, choosing not to offer himself for interviews or photo opportunities as often as his predecessor had.[24] His administration marked a change in style from the charismatic leadership of Roosevelt to Taft's quieter passion for the rule of law.[25]

Judicial appointments

Taft made six appointments to the Supreme Court, the most of any president except George Washington and Franklin D. Roosevelt.[26]

- Horace H. Lurton – Associate Justice (to replace Rufus Peckham),

nominated December 13, 1909 and confirmed by the U.S. Senate December 20, 1909[27][28] - Charles Evans Hughes – Associate Justice (to replace David Josiah Brewer),

nominated April 25, 1910 and confirmed by the U.S. Senate May 2, 1910[27][28] - Edward Douglass White – Chief Justice (to replace Melville Fuller),

nominated December 12, 1910 and confirmed by the U.S. Senate December 12, 1910[27][28]

(White was the first sitting associate justice to be elevated to chief justice. The nomination of a sitting associate justice to be chief justice is subject to a separate confirmation process.) - Willis Van Devanter – Associate Justice (to fill the vacancy left by Edward Douglass White's elevation to chief justice),

nominated December 12, 1910 and confirmed by the U.S. Senate December 15, 1910[27][28] - Joseph R. Lamar – Associate Justice (to replace William Henry Moody),

nominated December 12, 1910 and confirmed by the U.S. Senate December 15, 1910[27][28] - Mahlon Pitney – Associate Justice (to replace John Marshall Harlan),

nominated February 19, 1912 and confirmed by the U.S. Senate March 13, 1912[27][28]

The Court under Chief Justice White proved to be less conservative than both the preceding Fuller Court and the succeeding Taft Court, although the court continued to strike down numerous economic regulations as part of the Lochner era. Three of Taft's appointees had left the court by 1917, while Pitney and White remained on the court until the early 1920s. The conservative Van Devanter was the lone Taft appointee to serve past 1922, and he formed part of the Four Horsemen bloc that opposed Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal. Taft himself would succeed White as Chief Justice in 1921, and he served with Pitney and Van Devanter on the Taft Court.[29]

Taft also appointed 13 judges to the federal courts of appeal and 38 judges to the United States district courts. Taft also appointed judges to various specialized courts, including the first five appointees each to the United States Commerce Court and the United States Court of Customs Appeals.[30]

Foreign affairs

Organization and principles

Taft made it a priority to restructure the State Department, noting, "it is organized on the basis of the needs of the government in 1800 instead of 1900."[31] The Department was for the first time organized into geographical divisions, including desks for the Far East, Latin America and Western Europe.[32] The department's first in-service training program was established, and appointees spent a month in Washington before going to their posts.[33] Taft and Secretary of State Knox had a strong relationship, and the president listened to his counsel on matters foreign and domestic. According to Coletta, however, Knox was not a good diplomat, and had poor relations with the Senate, press, and many foreign leaders, especially those from Latin America.[34]

There was broad agreement between Taft and Knox on major foreign policy goals; the U.S. would not interfere in European affairs, and would use force if necessary to uphold the Monroe Doctrine in the Americas. The defense of the Panama Canal, which was under construction throughout Taft's term (it opened in 1914), guided United States foreign policy in the Caribbean and Central America. Previous administrations had made efforts to promote American business interests overseas, but Taft went a step further and used the web of American diplomats and consuls abroad to further trade. Such ties, Taft hoped, would promote world peace.[34] Taft pushed for arbitration treaties with Great Britain and France, but the Senate was not willing to yield its constitutional prerogative to approve treaties to arbitrators.[35]

Proposed free trade accord with Canada

In Taft's annual message sent to Congress in December 1910, he urged a free trade accord for Canada. Britain at that time still handled Canada's foreign relations, and Taft found the British and Canadian governments willing. Many in Canada opposed an accord, fearing the U.S. would dump it when convenient as it had the 1854 Elgin-Marcy Treaty in 1866, and American farm and fisheries interests were also opposed. After January 1911 talks with Canadian officials, Taft had the agreement, which was not a treaty, introduced into Congress and it passed in late July. The Canadian Parliament, led by Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier, had deadlocked over the issue. Canadians turned Laurier out of office in the September 1911 election and Robert Borden became the new prime minister. No cross-border agreement was concluded, and the debate deepened divisions in the Republican Party.[36][37]

Latin America

Taft and Secretary of State Knox instituted a policy of Dollar Diplomacy towards Latin America, believing U.S. investment would benefit all involved, while keeping European influence away from areas subject to the Monroe Doctrine. Although exports rose sharply during Taft's administration, the policy was unpopular among Latin American states that did not wish to become financial protectorates of the United States, as well as in the U.S. Senate, many of whose members believed the U.S. should not interfere abroad.[38] No foreign affairs controversy tested Taft's statesmanship and commitment to peace more than the collapse of the Mexican regime and subsequent turmoil of the Mexican Revolution.[39]

When Taft entered office, Mexico was increasingly restless under the grip of longtime dictator Porfirio Díaz and many Mexicans backed his opponent, Francisco Madero.[40] There were a number of incidents in which Mexican rebels crossed the U.S. border to obtain horses and weapons; Taft sought to prevent this by ordering the army to the border areas for maneuvers. Taft told his military aide, Archibald Butt, that "I am going to sit on the lid and it will take a great deal to pry me off".[41] He showed his support for Díaz by meeting with him at El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, the first meeting between a U.S. and a Mexican president and also the first time an American president visited Mexico.[42] The day of the summit, Frederick Russell Burnham and a Texas Ranger captured and disarmed an assassin holding a palm pistol only a few feet of the two presidents.[42] Before the election in Mexico, Díaz jailed opposition candidate Madero, whose supporters took up arms resulting in both the ousting of Díaz and a revolution that would continue for another ten years. In the U.S.'s Arizona Territory, two citizens were killed and almost a dozen injured, some as a result of gunfire across the border. Taft would not be goaded into fighting and so instructed the territorial governor.[39]

In Nicaragua, American diplomats quietly favored rebel forces under Juan J. Estrada against the government of President, José Santos Zelaya, who wanted to revoke commercial concessions granted to American companies.[43] Secretary Knox was reportedly a major stockholder in one of the companies that would be hurt by such a move.[44] The country was in debt to several foreign powers, and the U.S. was unwilling to have it (along with its alternate canal route) fall into the hands of Europeans. Zelaya's elected successor, José Madriz, could not put down the rebellion as U.S. forces interfered, and in August 1910, Estrada's forces took Managua, the capital. The U.S. had Nicaragua accept a loan, and sent officials to ensure it was repaid from government revenues. The country remained unstable, and after another coup in 1911 and more disturbances in 1912, Taft sent troops; though most were soon withdrawn, some remained as late as 1933.[45][46]

Treaties among Panama, Colombia, and the United States to resolve disputes arising from the Panamanian Revolution of 1903 had been signed by the lame-duck Roosevelt administration in early 1909, and were approved by the Senate and also ratified by Panama. Colombia, however, declined to ratify the treaties, and after the 1912 elections, Knox offered $10 million to the Colombians (later raised to $25 million). The Colombians felt the amount inadequate, and requested arbitration; the matter was not settled under the Taft administration.[47]

Far East

Due to his years in the Philippines, Taft was keenly interested as president in Far Eastern affairs.[48] Taft considered relations with Europe relatively unimportant, but because of the potential for trade and investment, Taft ranked the post of minister to China as most important in the Foreign Service. Knox did not agree, and declined a suggestion that he go to Peking to view the facts on the ground. Taft replaced Roosevelt's minister there, William W. Rockhill, as uninterested in the China trade, with William J. Calhoun, whom McKinley and Roosevelt had sent on several foreign missions. Knox did not listen to Calhoun on policy, and there were often conflicts.[49] Taft and Knox tried unsuccessfully to extend John Hay's Open Door Policy to Manchuria.[50]

In 1898, an American company had gained a concession for a railroad between Hankow and Szechuan, but the Chinese revoked the agreement in 1904 after the company (which was indemnified for the revocation) breached the agreement by selling a majority stake outside the United States. The Chinese imperial government got the money for the indemnity from the British Hong Kong government, on condition British subjects would be favored if foreign capital was needed to build the railroad line, and in 1909, a British-led consortium began negotiations.[51] This came to Knox's attention in May of that year, and he demanded that U.S. banks be allowed to participate. Taft appealed personally to the Prince Regent, Zaifeng, Prince Chun, and was successful in gaining U.S. participation, though agreements were not signed until May 1911.[52] However, the Chinese decree authorizing the agreement also required the nationalization of local railroad companies in the affected provinces. Inadequate compensation was paid to the shareholders, and these grievances were among those which touched off the Chinese Revolution of 1911.[53][54]

After the revolution broke out, the revolt's leaders chose Sun Yat Sen as provisional president of what became the Republic of China, overthrowing the Manchu Dynasty, Taft was reluctant to recognize the new government, although American public opinion was in favor of it. The U.S. House of Representatives in February 1912 passed a resolution supporting a Chinese republic, but Taft and Knox felt recognition should come as a concerted action by Western powers. Taft in his final annual message to Congress in December 1912 indicated that he was moving towards recognition once the republic was fully established, but by then he had been defeated for re-election and he did not follow through.[55]

Taft continued the policy against immigration from China and Japan as under Roosevelt. A revised treaty of friendship and navigation entered into by the U.S. and Japan in 1911 granted broad reciprocal rights to Japanese in America and Americans in Japan, but were premised on the continuation of the Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907. There was objection on the West Coast when the treaty was submitted to the Senate, but Taft informed politicians that there was no change in immigration policy.[56]

Europe

Taft was opposed to the traditional practice of rewarding wealthy supporters with key ambassadorial posts, preferring that diplomats not live in a lavish lifestyle and selecting men who, as Taft put it, would recognize an American when they saw one. High on his list for dismissal was the ambassador to France, Henry White, whom Taft knew and disliked from his visits to Europe. White's ousting caused other career State Department employees to fear that their jobs might be lost to politics. Taft also wanted to replace the Roosevelt-appointed ambassador in London, Whitelaw Reid, but Reid, owner of the New-York Tribune, had backed Taft during the campaign, and both William and Nellie Taft enjoyed his gossipy reports. Reid remained in place until his 1912 death.[57]

Taft was a supporter of settling international disputes by arbitration, and he negotiated treaties with Great Britain and with France providing that differences be arbitrated. These were signed in August 1911. Neither Taft nor Knox (a former senator) consulted with members of the Senate during the negotiating process. By then many Republicans were opposed to Taft and the president felt that lobbying too hard for the treaties might cause their defeat. He made some speeches supporting the treaties in October, but the Senate added amendments Taft could not accept, killing the agreements.[58]

Although no general arbitration treaty was entered into, Taft's administration settled several disputes with Great Britain by peaceful means, often involving arbitration. These included a settlement of the boundary between Maine and New Brunswick, a long-running dispute over seal hunting in the Bering Sea that also involved Japan, and a similar disagreement regarding fishing off Newfoundland. The sealing convention remained in force until abrogated by Japan in 1940.[59]

Unlike his predecessor, Taft did not seek to arbitrate conflicts among the other great powers. Taft avoided involvement in international events such as the Agadir Crisis, the Italo-Turkish War, and the First Balkan War. However, Taft did express support for the creation of an international arbitration tribunal and called for an international arms reduction agreement.[60]

Domestic affairs

Tariffs

Immediately following his inauguration, Taft called a special session of Congress to convene in March 1909 for the purpose of revising the tariff schedules.[61] Rates at the time were being set in accordance with the 1897 Dingley Act, and were the highest in U.S. history. The Republican Party had made the high tariff the central plank of their economic policy since the end of the Civil War, but Taft and some other Republicans had come to believe that the Dingley Act had set the rates too high. Though the high tariff protected domestic manufacturing, it also hurt U.S. exports and raised the cost of living for the average American. Roosevelt had largely avoided the tariff issue, but Taft became the first Republican president to actively seek to lower tariff rates.[62]

Congressman Sereno E. Payne, chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, had held hearings on tariff reform in late 1908, and sponsored the resulting draft legislation. On balance, the bill reduced tariffs slightly, but when it passed the House in April 1909 and reached the Senate, the chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, Nelson W. Aldrich, attached numerous amendments, all of which raised rates. This outraged progressives such as Wisconsin's Robert M. La Follette, who urged Taft to say that the bill was not in accord with the party platform.[63] They forced a protracted debate on the bill, but were unable in the end to stop it from being adopted. A conference committee reconciled the two bills, and both houses passed the compromise, which Taft signed into law on August 6, 1909.

Taft favored the House bill due to the more substantial rate reductions it contained and would have preferred more substantial reductions than those provided by the tariff rates. However, he feared potentially dividing his party by wielding his veto power.[64] The Payne-Aldrich tariff greatly disappointed progressive Republicans, and the disharmony in the Republican Party received widespread exposure in the press, providing the Democrats with a powerful campaign issue for the 1910 congressional elections. The wounds inflicted during the tariff debate never healed.[65]

Antitrust

Taft continued and expanded Roosevelt's efforts to break up business combinations through lawsuits brought under the Sherman Antitrust Act, bringing 70 cases in four years (Roosevelt had brought 40 in seven years). Suits brought against the Standard Oil Company and the American Tobacco Company, initiated under Roosevelt, were decided in favor of the government by the Supreme Court in 1911.[66] In June 1911, the Democrat-controlled House of Representatives began hearings into United States Steel (U.S. Steel). That company had been expanded under Roosevelt, who had supported its acquisition of the Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company as a means of preventing the deepening of the Panic of 1907, a decision the former president defended when testifying at the hearings. Taft, as Secretary of War, had praised the acquisitions.[67] Historian Louis L. Gould suggested that Roosevelt was likely deceived into believing that U.S. Steel did not want to purchase the Tennessee company, but it was in fact a bargain. For Roosevelt, questioning the matter went to his personal honesty.[68]

In October 1911, Taft's Justice Department brought suit against U.S. Steel, demanding that over a hundred of its subsidiaries be granted corporate independence, and naming as defendants many prominent business executives and financiers. The pleadings in the case had not been reviewed by Taft, and alleged that Roosevelt "had fostered monopoly, and had been duped by clever industrialists".[67] Roosevelt was offended by the references to him and his administration in the pleadings, and felt that Taft could not evade command responsibility by saying he did not know of them.[69]

Taft sent a special message to Congress on the need for a revamped antitrust statute when it convened its regular session in December 1911, but it took no action. Another antitrust case that had political repercussions for Taft was that brought against the International Harvester Company, the large manufacturer of farm equipment, in early 1912. As Roosevelt's administration had investigated International Harvester, but had taken no action (a decision Taft had supported), the suit became caught up in Roosevelt's challenge for the Republican presidential nomination. Supporters of Taft alleged that Roosevelt had acted improperly; the former president blasted Taft for waiting three and a half years, and until he was under challenge, to reverse a decision he had supported.[70]

Ballinger–Pinchot affair

Roosevelt was an ardent conservationist, assisted in this by like-minded appointees, including Interior Secretary James R. Garfield (son of President James A. Garfield) and Chief Forester Gifford Pinchot. Taft agreed with the need for conservation, but felt it should be accomplished by legislation rather than executive order. He did not retain Garfield, an Ohioan, as secretary, choosing instead a westerner, former Seattle mayor Richard Ballinger. Roosevelt was surprised at the replacement, believing that Taft had promised to keep Garfield, and this change was one of the events that caused Roosevelt to realize that Taft would pursue different policies.[71]

Roosevelt had withdrawn much land from the public domain, including some in Alaska thought rich in coal. In 1902, Clarence Cunningham, an Idaho entrepreneur, had found coal deposits in Alaska, and made mining claims, and the government investigated their legality. This dragged on for the remainder of the Roosevelt administration, including during the year (1907–1908) when Ballinger served as head of the General Land Office.[72] A special agent for the Land Office, Louis Glavis, investigated the Cunningham claims, and when Secretary Ballinger in 1909 approved them, Glavis broke governmental protocol by going outside the Interior Department to seek help from Pinchot.[73]

In September 1909, Glavis made his allegations public in a magazine article, disclosing that Ballinger had acted as an attorney for Cunningham between his two periods of government service. This violated conflict of interest rules forbidding a former government official from advocacy on a matter he had been responsible for.[74] On September 13, 1909 Taft dismissed Glavis from government service, relying on a report from Attorney General George W. Wickersham dated two days previously.[75] Pinchot was determined to dramatize the issue by forcing his own dismissal, which Taft tried to avoid, fearing that it might cause a break with Roosevelt (still overseas). Taft asked Elihu Root (by then a senator) to look into the matter, and Root urged the firing of Pinchot.[74]

Taft had ordered government officials not to comment on the fracas.[76] In January 1910, Pinchot forced the issue by sending a letter to Iowa Senator Dolliver alleging that but for the actions of the Forestry Service, Taft would have approved a fraudulent claim on public lands. According to Pringle, this "was an utterly improper appeal from an executive subordinate to the legislative branch of the government and an unhappy president prepared to separate Pinchot from public office".[77] Pinchot was dismissed, much to his delight, and he sailed for Europe to lay his case before Roosevelt.[78] A congressional investigation followed, which cleared Ballinger by majority vote, but the administration was embarrassed when Glavis' attorney, Louis D. Brandeis, proved that the Wickersham report had been backdated, which Taft belatedly admitted. The Ballinger–Pinchot affair caused progressives and Roosevelt loyalists to feel that Taft had turned his back on Roosevelt's agenda.[79]

Civil rights

Taft announced in his inaugural address that he would not appoint African Americans to federal jobs, such as postmaster, where this would cause racial friction. This differed from Roosevelt, who would not remove or replace black officeholders with whom local whites would not deal. Termed Taft's "Southern Policy", this stance effectively invited white protests against black appointees. Taft followed through, removing most black office holders in the South, and made few appointments from that race in the North.[80]

At the time Taft was inaugurated, the way forward for African Americans was debated by their leaders. Booker T. Washington felt that most blacks should be trained for industrial work, with only a few seeking higher education; W.E.B. DuBois took a more militant stand for equality. Taft tended towards Washington's approach. According to Coletta, Taft let the African-American "be 'kept in his place' ... He thus failed to see or follow the humanitarian mission historically associated with the Republican party, with the result that Negroes both North and South began to drift toward the Democratic party."[81]

Other initiatives

Taft sought greater regulation of railroads, and he proposed the creation of the United States Commerce Court to hear appeals from the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), which provided federal oversight to railroads and other common carriers engaged in interstate commerce. The Mann–Elkins Act established the Commerce Court and increased the authority of the ICC, placing telegraph and telephone companies under its authority and allowing it to set price ceilings on rail fares.[82] The Commerce Court proved to be unpopular with members of Congress, and it was abolished in 1913.[83]

Taft proposed that the Post Office Department act as a bank that would accept small deposits. Though the idea was opposed by conservative Republicans such as Senator Aldrich and Speaker of the House Joseph Cannon, Taft won passage of a law establishing the United States Postal Savings System. Taft also oversaw the establishment of a domestic parcel post delivery system.[84]

The results from the 1910 midterm elections were disappointing to the president, as Democrats took control of the House and many of Taft's preferred candidates were defeated. The election was a major victory for progressives in both parties, and ultimately helped encourage Roosevelt's 1912 third party run.[85] Taft was also disappointed by the defeat of Warren G. Harding in the 1910 Ohio gubernatorial race, while in New Jersey, Democrat Woodrow Wilson was elected governor.[86] With a divided government, the second half of Taft's term saw the passage of much less legislation than the first.[87]

Constitutional amendments

Among the provisions attached to tariff reform legislation being considered by the Senate Finance Committee in 1909 was one imposing a general income tax. Taft opposed its inclusion in the bill because in form and substance it was almost exactly the same as an earlier tax that the Supreme Court struck down as unconstitutional in Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co. (1895). As an alternative, the president encouraged Congress to propose a constitutional amendment allowing the Congress to levy an income tax without apportioning it among the states or basing it on the United States Census.[88] An amendment to the Constitution expanding the authority of Congress to levy an income tax was approved by Congress on July 12, 1909, and submitted it to the state legislatures for ratification. By February 3, 1913 it had been ratified by the requisite number of states (36) to become the Sixteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.[89][90]

For the first 125 years of the federal government's existence Americans did not directly vote for U.S. Senators. The Constitution, as it was adopted in 1788, stated that senators would be elected by state legislatures. During the 1890s, the House of Representatives passed several resolutions proposing a constitutional amendment for the direct election of senators. Each time, however, the Senate refused to even take a vote. Additionally, a number of states began calling for a constitutional convention on the subject. Article V of the Constitution states that Congress must call a constitutional convention for proposing amendments when two-thirds of the state legislatures apply for one.[91] By 1912, 27 states had called for a constitutional convention on the subject, with 31 states needed to reach the threshold.[92] As the number of applications neared the two-thirds threshold, the Senate abandoned its strategy of obstruction. An amendment to the Constitution establishing the popular election of United States Senators by the people of the states was approved by Congress on May 13, 1912, and submitted it to the state legislatures for ratification. By April 8, 1913 it had been ratified by the requisite number of states (36) to become the Seventeenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.[89][90]

States admitted to the Union

Since Oklahoma's admission in 1907, there had been 46 states in the union, with New Mexico Territory and Arizona Territory still remaining in the Contiguous United States. The Enabling Act of 1906 would have allowed Arizona and New Mexico to join the union as one state, but Arizona had voted against the combination in a referendum.[93][94] In 1910, New Mexico and Arizona both wrote a constitution in anticipation of statehood, and Arizona's constitution included progressive ideas such as initiative, referendum, and recall. Taft opposed these mechanisms, particularly the ability to recall judges, and he vetoed Arizona's statehood bill.[93] Without any such constitutional issues, New Mexico joined the union as the 47th state on January 6, 1912.[94] After Arizona wrote a new constitution removing the power to recall judges, Taft signed a bill admitting Arizona on February 14, 1912.[93]

Moving apart from Roosevelt

During Roosevelt's fifteen months beyond the Atlantic, from March 1909 to June 1910, neither man wrote much to the other. Taft biographer Lurie suggested that each expected the other to make the first move to re-establish their relationship on a new footing. Upon Roosevelt's triumphant return, Taft invited him to stay at the White House. The former president declined, and in private letters to friends expressed dissatisfaction at Taft's performance. Nevertheless, he wrote that he expected Taft to be renominated by the Republicans in 1912, and did not speak of himself as a candidate.[95] Taft and Roosevelt met twice in 1910; the meetings, though outwardly cordial, did not display their former closeness.[86]

After returning from Europe, Roosevelt gave a series of speeches in the West in the late summer and early fall of 1910. Roosevelt not only attacked the Supreme Court's 1905 decision in Lochner v. New York, he accused the federal courts of undermining democracy, and called for them to be deprived of the power to rule legislation unconstitutional. This attack horrified Taft, who privately agreed that Lochner had been wrongly decided but strongly supported judicial review. Roosevelt called for "elimination of corporate expenditures for political purposes, physical valuation of railroad properties, regulation of industrial combinations, establishment of an export tariff commission, a graduated income tax" as well as "workmen's compensation laws, state and national legislation to regulate the [labor] of women and children, and complete publicity of campaign expenditure".[96] According to John Murphy in his journal article on the breach between the two presidents, "As Roosevelt began to move to the left, Taft veered to the right."[96] Taft had become increasingly associated with the conservative "Old Guard" faction of the party, and progressive Republicans such as Wisconsin Senator Robert La Follette became dissatisfied Taft's leadership.[97] La Follette and his followers formed the National Republican Progressive League as a platform to challenge Taft in 1912 presidential election, either for the Republican nomination or in the general election as a third party.[98]

Election of 1912

After the 1910 election, Roosevelt continued to promote progressive ideals, a New Nationalism, much to Taft's dismay. Roosevelt attacked his successor's administration, arguing that its guiding principles were not that of the party of Lincoln, but those of the Gilded Age.[99] The feud continued on and off through 1911, a year in which there were few elections of significance. Backed by many progressives, La Follette announced a run for the 1912 Republican nomination. Roosevelt began to move into a position for a run in late 1911, writing that the tradition that presidents not run for a third term only applied to consecutive terms (in 1951, the 22nd Amendment would impose a two-term limit on presidents).[100]

Roosevelt was receiving many letters from supporters urging him to run, and Republican office-holders were organizing on his behalf. Balked on many policies by an unwilling Congress and courts in his full term in the White House, he saw manifestations of public support he believed would sweep him to the White House with a mandate for progressive policies that would brook no opposition.[101] In February 1912, Roosevelt announced he would accept the Republican nomination if it was offered to him, and many progressives abandoned La Follette's candidacy and backed Roosevelt.[102]

As Roosevelt became more radical in his progressivism, Taft was hardened in his resolve to achieve re-nomination, as he was convinced that the progressives threatened the very foundation of the government.[103] While Roosevelt attacked both parties as corrupt and overly dependent on special interests, Taft feared that Roosevelt was becoming a demagogue.[104] Despite Roosevelt's popularity, Taft still held the loyalty of many Republican leaders, giving him a major advantage in the race for delegates. In an effort to shore up his support, Taft hit the campaign trail, becoming the first sitting president to do so during a primary campaign.[105]

Roosevelt dominated the primaries, winning 278 of the 362 delegates to the Republican National Convention in Chicago decided in that manner. Taft's control of the party machinery proved critical in helping him win the bulk of the delegates decided at district or state conventions.[106] At the start of the convention, Taft did not have a majority of the delegates, but was likely to have one once southern delegations committed to him. Roosevelt challenged the election of these delegates, but the RNC overruled most objections. Roosevelt's sole remaining chance was with a friendly convention chairman, who might make rulings on the seating of delegates that favored his side. Taft followed custom and remained in Washington, but Roosevelt went to Chicago to run his campaign[107] and told his supporters in a speech, "we stand at Armageddon, and we battle for the Lord".[108]

Taft had won over Root, who agreed to run for temporary chairman of the convention, and the delegates elected Root over Roosevelt's candidate.[108] The Roosevelt forces moved to substitute the delegates they supported for the ones they argued should not be seated. Root made a crucial ruling, that although the contested delegates could not vote on their own seating, they could vote on the other contested delegates, a ruling that assured Taft's nomination, as the motion offered by the Roosevelt forces failed, 567—507.[109] As it became clear Roosevelt would bolt the party if not nominated, some Republicans sought a compromise candidate to avert the electoral disaster to come; they were unsuccessful.[110] Taft's name was placed in nomination by Warren Harding, whose attempts to praise Taft and unify the party were met with angry interruptions from progressives.[111] Taft was nominated on the first ballot, though most Roosevelt delegates refused to vote.[109] Vice President Sherman was also nominated for a second term. This made him the first incumbent vice president to win re-nomination since John C. Calhoun in 1828.

Alleging Taft had stolen the nomination, Roosevelt and his followers formed the Progressive Party, commonly known as the "Bull Moose Party."[112] Taft knew he would almost certainly be defeated, but concluded that through Roosevelt's loss at Chicago the party had been preserved as "the defender of conservative government and conservative institutions."[113] He made his doomed run to preserve the Republican Party.[114] Governor Woodrow Wilson was the Democratic nominee. Seeing Roosevelt as the greater electoral threat, Wilson spent little time attacking Taft, arguing that Roosevelt had been lukewarm in opposing the trusts during his presidency, and that Wilson was the true reformer.[115] Taft contrasted what he called his "progressive conservatism" with Roosevelt's Progressive democracy, which to Taft represented "the establishment of a benevolent despotism."[116]

During his 1912 quest for the presidency Roosevelt brought together a coalition of public advocacy groups, many of which became core constituencies of contemporary American progressivism. His campaign also made effective use of mass media. This included both traditional mediums – newspapers and magazines, as well as emergent mediums, such as motion pictures, which featured campaign advertisements for the first time.[116] Roosevelt visited 38 states during the campaign. While in Milwaukee, Wisconsin on October 14, 1912, he was shot by John Schrank as he left the Hotel Gilpatrick for a campaign appearance. The bullet lodged in his chest, but after hitting both his steel eyeglass case and a 50-page copy of his speech, which were in the breast pocket of his heavy overcoat. Realizing that he wasn't in any immediate danger from the wound, Roosevelt brushed aside suggestions that he go to the hospital, proceeded to deliver his scheduled speech.[117]

Reverting to the 19th century custom that presidents seeking re-election did not campaign, Taft retreated to the golf links.[2] He spoke publicly only once, when making his nomination acceptance speech on August 1. He had difficulty in financing the campaign, as many industrialists had concluded he could not win, and would support Wilson to block Roosevelt. The president issued a confident statement in September after the Republicans narrowly won Vermont's state elections in a three-way fight, but had no illusions he would win his race.[118] He had hoped to send his cabinet officers out on the campaign trail, but found them reluctant to go. Senator Root agreed to give a single speech for him.[119] Any remaining sense of optimism within the campaign evaporated when Vice President Sherman became seriously ill in October, and died six days before the election. It wasn't until January (two months after the election) that the Republican National Committee named Columbia University president Nicholas Murray Butler to replace Sherman and to receive his electoral votes.[23]

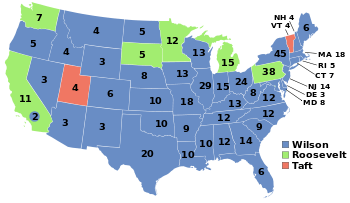

Taft won only Utah and Vermont, for a total of eight electoral votes, which set a record for electoral vote futility by a Republican candidate; one subsequently matched by Alf Landon in 1936.[23] Roosevelt won 88 electoral votes, while Wilson won 435; Wilson's share of the electoral vote represented the best Democratic showing since the 1852 election. In the popular vote, Wilson 41.8 percent, while Roosevelt won 27.4 percent, and Taft took 23.2 percent. Democrats won control of not just the presidency but also both houses of Congress, giving them unified control of the executive and legislative branches for the first time since the 1894 election.[120]

Historical reputation

Lurie argued that Taft did not receive the public credit for his policies that he should have. Few trusts had been broken up under Roosevelt (although the lawsuits received much publicity). Moreover, he was not an effective political writer or speaker.[121] Nonetheless, Taft, more quietly than his predecessor, filed many more cases than did Roosevelt, and rejected his predecessor's contention that there was such a thing as a "good" trust. This lack of flair marred Taft's presidency; according to Lurie, Taft "was boring—honest, likable, but boring".[122] Scott Bomboy for the National Constitution Center wrote that despite being "one of the most interesting, intellectual, and versatile presidents ... a chief justice of the United States, a wrestler at Yale, a reformer, a peace activist, and a baseball fan ... today, Taft is best remembered as the president who was so large that he got stuck in the White House bathtub," a story that is not true.[114]

Mason called Taft's years in the White House "undistinguished".[123] Coletta deemed Taft to have had a solid record of bills passed by Congress, but felt he could have accomplished more with political skill.[124] Anderson noted that Taft's pre-presidential federal service was entirely in appointed posts, and that he had never run for an important executive or legislative position, which would have allowed him to develop the skills to manipulate public opinion, "the presidency is no place for on-the-job training".[125] According to Coletta, "in troubled times in which the people demanded progressive change, he saw the existing order as good."[126]

Inevitably linked with Roosevelt, Taft generally falls in the shadow of the flamboyant Rough Rider, who chose him to be president, and who took it away.[127] Yet, a portrait of Taft as a victim of betrayal by his best friend is incomplete: as Coletta put it, "Was he a poor politician because he was victimized or because he lacked the foresight and imagination to notice the storm brewing in the political sky until it broke and swamped him?"[128] Adept at using the levers of power in a way his successor could not, Roosevelt generally got what was politically possible out of a situation. Taft was generally slow to act, and when he did, his actions often generated enemies, as in the Ballinger–Pinchot affair. Roosevelt was able to secure positive coverage in the newspapers; Taft had a judge's reticence in talking to reporters, and, with no comment from the White House, hostile journalists would supply the want with a quote from a Taft opponent.[129] And it was Roosevelt who engraved in public memory the image of Taft as a Buchanan-like figure, with a narrow view of the presidency which made him unwilling to act for the public good. Anderson pointed out that Roosevelt's Autobiography (which placed this view in enduring form) was published after both men had left the presidency (in 1913), was intended in part to justify Roosevelt's splitting of the Republican Party, and contains not a single positive reference to the man Roosevelt had admired and hand-picked as his successor. While Roosevelt was biased,[130] he was not alone: every major newspaper reporter of that time who left reminiscences of Taft's presidency was critical of him.[131] Taft replied to his predecessor's criticism with his constitutional treatise on the powers of the presidency.[130]

Taft was convinced he would be vindicated by history. After he left office, he was estimated to be about in the middle of U.S. presidents by greatness, and subsequent rankings by historians have by and large sustained that verdict. In a 2017 C-SPAN survey 91 presidential historians ranked Taft 24th among the 43 former presidents, including then-president Barack Obama (unchanged from his ranking in 2009 and 2000). His rankings in the various categories of this most recent poll were as follows: public persuasion (31), crisis leadership (26), economic management (20), moral authority (25), international relations (21), administrative skills (12), relations with congress (23), vision/setting an agenda (28), pursued equal justice for all (22), performance with context of times (24).[132] A 2018 poll of the American Political Science Association's Presidents and Executive Politics section ranked Taft as the 25th best president.[133]

References

- 1 2 Anderson 1973, p. 37.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "William Taft:Campaigns and Elections". Charlottesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved July 9, 2017.

- ↑ Pringle vol 1, pp. 321–322.

- ↑ Pringle vol 1, pp. 337–338.

- ↑ Pringle vol 1, p. 347.

- ↑ Pringle vol 1, pp. 348–353.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, p. 15.

- ↑ Morris, p. 529.

- ↑ Goodman, Bonnie K. (ed.). "Overviews & Chronologies: 1908". Presidential Campaigns & Elections Reference: An American History Resource. Retrieved July 9, 2017.

- ↑ Roberts, Robert North; Hammond, Scott J.; Sulfaro, Valerie A. (2012). Presidential Campaigns, Slogans, Issues, and Platforms: The Complete Encyclopedia. Volume 1: Slogans, Issues, Programs, Personalities and Strategies. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 263. ISBN 978-0-313-38093-8.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Pringle vol 1, pp. 358–360.

- ↑ Lurie, p. 136.

- ↑ Anderson 1973, p. 57.

- ↑ Anderson 1973, p. 58.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, p. 19.

- ↑ "Travels of President William Howard Taft". Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of State Office of the Historian. Retrieved July 9, 2017.

- ↑ Pringle vol 1, pp. 393–395.

- ↑ Pringle vol 1, p. 395.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, p. 45.

- ↑ Pringle vol 1, pp. 383–387.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, pp. 49–50.

- 1 2 3 "James S. Sherman, 27th Vice President (1909-1912)". Washington, D.C.: U.S. Senate. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ↑ Rouse, Robert (March 15, 2006). "Happy Anniversary to the first scheduled presidential press conference – 93 years young!". American Chronicle.

- ↑ Anderson 1973, p. 60.

- ↑ Anderson 2000, p. 332.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "U.S. Senate: Supreme Court Nominations: 1789-Present". www.senate.gov. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lurie, p. 121, 123–128.

- ↑ Galloway, Jr., Russell Wl (January 1, 1985). "The Taft Court (1921-29)". Santa Clara Law Review. 25 (1): 1–2. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- ↑ "Biographical Dictionary of the Federal Judiciary". Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved February 13, 2016. searches run from page, "select research categories" then check "court type" and "nominating president", then select the court type and also William H. Taft.

- ↑ Anderson 1973, p. 68.

- ↑ Anderson 1973, p. 71.

- ↑ Scholes and Scholes, p. 25.

- 1 2 Coletta 1973, pp. 183–185.

- ↑ Anderson 1973, pp. 276–278.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, pp. 141–152.

- ↑ Pringle vol 2, pp. 593–595.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, pp. 185, 190.

- 1 2 Anderson 1973, p. 271.

- ↑ Burton 2004, p. 70.

- ↑ Burton 2004, p. 72.

- 1 2 Harris 2009, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Burton 2004, pp. 66–67.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, p. 188.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, pp. 187–190.

- ↑ Burton 2004, pp. 67–69.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, pp. 186–187.

- ↑ Scholes and Scholes, p. 109.

- ↑ Scholes and Scholes, pp. 21–23.

- ↑ Anderson 1973, pp. 250–255.

- ↑ Scholes and Scholes, pp. 126–129.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, pp. 194–195.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, p. 196.

- ↑ Scholes and Scholes, pp. 217–221.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, pp. 198–199.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, pp. 199–200.

- ↑ Scholes and Scholes, pp. 19–21.

- ↑ Burton 2004, pp. 82–83.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, pp. 168–169.

- ↑ Sprout, Harold Hance; Sprout, Margaret (8 December 2015). Rise of American Naval Power. Princeton University Press. pp. 286–288.

- ↑ Korzi, pp. 307-308.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, pp. 56–57.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, pp. 60–65.

- ↑ Korzi, pp. 308-309.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, pp. 65–71.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, pp. 154–157.

- 1 2 Coletta 1973, pp. 157–159.

- ↑ Lurie, pp. 145–147.

- ↑ Lurie, p. 149.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, pp. 160–163.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, pp. 77–82.

- ↑ Pringle vol 1, pp. 483–485.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, pp. 85–86, 89.

- 1 2 Coletta 1973, pp. 89–92.

- ↑ Pringle vol 1, p. 510.

- ↑ Lurie, p. 113.

- ↑ Pringle vol 1, pp. 507–509.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, p. 94.

- ↑ Pringle vol 1, pp. 509–513.

- ↑ Harlan, Louis R. (1983). Booker T. Washington : Volume 2: The Wizard Of Tuskegee, 1901–1915. USA,: Oxford University Press. p. 341. ISBN 0-19-972909-3.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, p. 30.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, pp. 126–129.

- ↑ "Commerce Court, 1910–1913". Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved February 13, 2016.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, pp. 125–126, 255.

- ↑ Busch, Andrew (1999). Horses in Midstream. University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 84–87.

- 1 2 Pringle vol 2, pp. 569–579.

- ↑ Korzi, pp. 310-311.

- ↑ "William Howard Taft: Special Message, June 16, 1909". University of California, Santa Barbara: Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, American Presidency Project. Retrieved April 29, 2017.

- 1 2 Huckabee, David C. (September 30, 1997). "Ratification of Amendments to the U.S. Constitution" (PDF). Congressional Research Service reports. Washington D.C.: Congressional Research Service, The Library of Congress.

- 1 2 "U.S. Constitution: Amendments". FindLaw. Retrieved April 29, 2017.

- ↑ "17th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Direct Election of U.S. Senators". Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved April 29, 2017.

- ↑ Rossum, Ralph A. (1999). "The Irony of Constitutional Democracy: Federalism, the Supreme Court, and the Seventeenth Amendment". San Diego Law Review. University of San Diego School of Law. 36 (3): 710. ISSN 0886-3210.

- 1 2 3 Bommersbach, Jana (February 13, 2012). "How Arizona almost didn't become a state". Arizona Central. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- 1 2 Linthicum, Leslie (October 23, 2013). "New Mexico's path to statehood often faltered". Albuquerque Journal. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ↑ Lurie, pp. 129–130.

- 1 2 Murphy, pp. 110–113.

- ↑ Korzi, pp. 309-310.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, pp. 219–221.

- ↑ Murphy, pp. 117–119.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, pp. 222–225.

- ↑ Pavord, pp. 635–640.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, pp. 225–226.

- ↑ Anderson 1973, pp. 183–185.

- ↑ Korzi, pp. 313-315.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, pp. 227–228.

- ↑ Hawley, p. 208.

- ↑ Lurie, pp. 163–166.

- 1 2 Hawley, p. 209.

- 1 2 Lurie, p. 166.

- ↑ Gould 2008, p. 72.

- ↑ Dean, pp. 29–30.

- ↑ Pavord, p. 643.

- ↑ Anderson 1973, p. 193.

- 1 2 Bomboy, Scott (February 6, 2013). "Clearing Up the William Howard Taft Bathtub Myth". National Constitution Center. Retrieved May 29, 2016.

- ↑ Hawley, pp. 213–218.

- 1 2 Milkis, Sidney M. (June 11, 2012). "The Transformation of American Democracy: Teddy Roosevelt, the 1912 Election, and the Progressive Party". First Principles. Washington, D.C.: The Heritage Foundation (No. 43). Retrieved July 9, 2017.

- ↑ O'Toole, Patricia (November 2012). "The Speech That Saved Teddy Roosevelt's Life". Smithsonian Magazine. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved July 9, 2017.

- ↑ Pringle vol 2, pp. 832–835.

- ↑ Lurie, pp. 169–171.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, pp. 245–246.

- ↑ Lurie, p. 198.

- ↑ Lurie, pp. 196–197.

- ↑ Mason, p. 36.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, pp. 259, 264–265.

- ↑ Anderson 1982, p. 27.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, p. 266.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, p. 260.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, p. 265.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, pp. 262–263.

- 1 2 Anderson 1982, pp. 30–32.

- ↑ Coletta 1973, p. 290.

- ↑ "Historians Survey Results: William H. Taft". Presidential Historians Survey 2017. National Cable Satellite Corporation. 2017. Retrieved April 28, 2017.

- ↑ Rottinghaus, Brandon; Vaughn, Justin S. (19 February 2018). "How Does Trump Stack Up Against the Best — and Worst — Presidents?". New York Times. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

Works cited

- Anderson, Donald F. (1973). William Howard Taft: A Conservative's Conception of the Presidency. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-0786-4.

- Anderson, Donald F. (Winter 1982). "The Legacy of William Howard Taft". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 12: 26–33. JSTOR 27547774.

- Anderson, Donald F. (Winter 2000). "Building National Consensus: The Career of William Howard Taft". University of Cincinnati Law Review. 68: 323–356.

- Burton, David H. (2004). William Howard Taft, Confident Peacemaker. Philadelphia: Saint Joseph's University Press. ISBN 0-916101-51-7.

- Coletta, Paolo Enrico (1973). The Presidency of William Howard Taft. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas.

- Dean, John W. (2004). Warren Harding (Kindle ed.). Henry Holt and Co. ISBN 0-8050-6956-9.

- Gould, Lewis L. (2014). Chief Executive to Chief Justice:Taft Betwixt the White House and Supreme Court. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-2001-2.

- Gould, Lewis L. (2008). Four Hats in the Ring: The 1912 Election and the Birth of Modern American Politics. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1564-3.

- Harris, Charles H. III; Sadler, Louis R. (2009). The Secret War in El Paso: Mexican Revolutionary Intrigue, 1906–1920. Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-4652-0.

- Hawley, Joshua David (2008). Theodore Roosevelt: Preacher of Righteousness. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-14514-4.

- Korzi, Michael J. (June 2003). "Our Chief Magistrate and His Powers: A Reconsideration of William Howard Taft's "Whig" Theory of Presidential Leadership". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 33 (2): 305–324. JSTOR 27552486.

- Lurie, Jonathan (2011). William Howard Taft: Progressive Conservative. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-51421-7.

- Mason, Alpheus Thomas (January 1969). "President by Chance, Chief Justice by Choice". American Bar Association Journal. 55 (1): 35–39. JSTOR 25724643.

- Morris, Edmund (2001). Theodore Rex. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-55509-6.

- Murphy, John (1995). "'Back to the Constitution': Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft and Republican Party Division 1910–1912". Irish Journal of American Studies. 4: 109–126. JSTOR 30003333.

- Pavord, Andrew C. (Summer 1996). "The Gamble for Power: Theodore Roosevelt's Decision to Run for the Presidency in 1912". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 26 (3): 633–647. JSTOR 27551622.

- Pringle, Henry F. (1939). The Life and Times of William Howard Taft: A Biography. 1 (2008 reprint ed.). Newtown, CT: American Political Biography Press. ISBN 978-0-945707-20-2.

- Pringle, Henry F. (1939). The Life and Times of William Howard Taft: A Biography. 2 (2008 reprint ed.). Newtown, CT: American Political Biography Press. ISBN 978-0-945707-19-6.

- Scholes, Walter V; Scholes, Marie V. (1970). The Foreign Policies of the Taft Administration. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0-8262-0094-X.

External links

Official

Speeches

- Text of a number of Taft speeches, Miller Center of Public Affairs

- Audio clips of Taft's speeches, Michigan State University Libraries

Media coverage

Other

- William Howard Taft: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- Extensive essay on William Howard Taft and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and the First Lady – Miller Center of Public Affairs

- "Life Portrait of William Howard Taft", from C-SPAN's American Presidents: Life Portraits, September 6, 1999

- "Growing into Public Service: William Howard Taft's Boyhood Home", a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

- Presidency of William Howard Taft at Curlie (based on DMOZ)

- Works by or about Presidency of William Howard Taft at Internet Archive

- William Howard Taft on IMDb

- Presidential Succession Historical Summary