Thomas Dixon Jr.

| Thomas Dixon Jr. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Thomas Frederick Dixon Jr. January 11, 1864 Shelby, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Died |

April 3, 1946 (aged 82) Raleigh, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Occupation | Novelist, playwright, minister, state legislator, lecturer |

| Nationality | American |

| Genre | Historical fiction |

| Literary movement | American Romanticism |

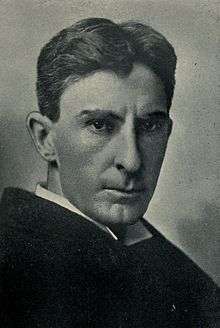

Thomas Frederick Dixon Jr. (January 11, 1864 – April 3, 1946) was a Southern Baptist minister, playwright, lecturer, politician, lawyer, and author who wrote two early 20th-century novels (The Leopard's Spots: A Romance of the White Man's Burden – 1865–1900 (1902) and The Clansman (1905)) that glorified the Ku Klux Klan's vigilantes, romanticized Southern white supremacy and opposed the equal rights for blacks during the Reconstruction era.[1] Film director D. W. Griffith adapted The Clansman for the screen in The Birth of a Nation (1915), which stimulated the formation of the 20th-century version of the Klan.

Early years

Dixon was born in Shelby, North Carolina, the son of Thomas Jeremiah Frederick Dixon II and Amanda Elvira McAfee.

Dixon's father, Thomas J. F. Dixon senior, was a slave-owner, landowner and Baptist minister of English and Scottish descent. Dixon Sr. had inherited slaves and property through his first wife's father.[2]

In his adolescence, Dixon helped out on the family farms, an experience that he hated, but he would later say that it helped him to relate to the plight of the working man.[3] Dixon grew up during Reconstruction after the Civil War. The government confiscation of farmland, coupled with what Dixon saw as the corruption of local politicians, the particular vengefulness of Union troops, and the general lawlessness embittered the young Dixon, who became staunchly opposed to reform.[4]

Dixon claimed that one of his earliest memories was of a widow of a Confederate soldier who had served under Dixon's uncle, Col. Leroy McAfee, had accused a black man of the rape of her daughter and sought the family's help. Dixon's mother praised the Klan after it had hanged and shot the alleged rapist in the town square.[5][6] It was a moment that etched itself into Dixon's memory; he felt that the Klan's actions were justified and that desperate times called for desperate measures.

Dixon's father, Thomas Dixon Sr., and his uncle, Leroy McAfee, both joined the Klan early in the Reconstruction era with the aim of "bringing order" to the tumultuous times. McAfee eventually attained the rank of Chief of the Klan of the Piedmont area of North Carolina.[6] However, after witnessing the corruption and scandal involved in the Klan, both men would dissolve their affiliation with the group and attempt to disband it within their region.[7]

Education

In 1877, Dixon entered the Shelby Academy, where he earned a diploma in only two years. In September 1879 Dixon enrolled at Wake Forest University, where he studied history and political science. As a student, Dixon performed remarkably well. In 1883, after only four years, he earned a master's degree. His record at Wake Forest was outstanding, and he earned the distinction of achieving the highest student honors ever awarded at the university until then.[8] As a student there, he was a founding member of the chapter of Kappa Alpha Order fraternity.[9] After his graduation from Wake Forest, Dixon received a scholarship to attend the Johns Hopkins University political science program. There he met and befriended future President Woodrow Wilson.[10] On January 11, 1884, despite the objections of Wilson, Dixon left Johns Hopkins University to pursue journalism and a career on the stage.

Dixon headed to New York City and enrolled in the Frobisher School of Drama to study drama. As an actor, Dixon's physical appearance became a problem. He was 6'3" but only 150 lb, making for a very lanky appearance. One producer remarked that because of his appearance, he would not succeed as an actor, but Dixon was complimented for his intelligence and attention to detail. The producer recommended Dixon to put his love for the stage into scriptwriting.[11] Despite the compliment, Dixon returned home to North Carolina in shame.

Upon his return to Shelby, Dixon quickly realized that he was in the wrong place to begin to cultivate his playwriting skills. After his initial disappointment from his rejection, Dixon, with the encouragement of his father, enrolled in the Greensboro Law School in Greensboro, North Carolina. An excellent student, Dixon received his law degree in 1885.[12]

Political career

It was during law school that Dixon's father convinced Thomas Jr. to enter politics. After graduation, Dixon ran for the local seat in the North Carolina General Assembly as a Democrat.[13] Despite being only 20 years of age and not even old enough to vote for himself, he won the election by a 2-1 margin, a victory that was attributed to his masterful oratory skills.[14] Dixon retired from politics in 1886 after only one term in the legislature. He said that he was disgusted by the corruption and the backdoor deals of the lawmakers, and he is quoted as referring to politicians as "the prostitutes of the masses."[15] However short, Dixon's political career gained him popularity throughout the South for his championing of Confederate veterans' rights.[16]

Following his career in politics, Dixon practiced private law for a short time, but he would find little satisfaction as a lawyer and would soon leave the profession to become a minister.

Ministry and lecturing

Dixon was ordained as a Baptist minister on October 6, 1886, with his first practice in Greensboro, where he had attended law school.[17] Church records show that in October 1886, Dixon moved to the parsonage at 125 South John Street in Goldsboro, North Carolina, to serve as the Pastor of the First Baptist Church. Already a lawyer and fresh out of Wake Forest Seminary, life in Goldsboro must not have been what young Dixon had been expecting for a first preaching assignment. The social upheaval that Dixon portrays in his later works was largely melded through Dixon's experiences in the post-war Wayne County during reconstruction.

On April 10, 1887, Dixon moved to the Second Baptist Church in Raleigh, North Carolina. His popularity rose quickly, and before long, he was offered a position at the Dudley Street Church in Boston, Massachusetts. As his popularity on the pulpit grew, so did his demand as a lecturer.[17] While preaching in Boston, Dixon was asked to give the commencement address at Wake Forest University. Additionally, he was offered a possible honorary doctorate from the university. Dixon himself rejected the offer, but he sang high praises about a then-unknown man Dixon believed deserved the honor, his old friend Woodrow Wilson.[18] A reporter at Wake Forest who heard Dixon's praises of Wilson put a story on the national wire, giving Wilson his first national exposure.[18]

In August 1889, Dixon accepted a post in New York City although his Boston congregation was willing to double his pay if stayed.[19] In New York City, Dixon would preach at new heights, bumping elbows with the likes of John D. Rockefeller and Theodore Roosevelt (whom he helped in a campaign for New York Governor).[19] Sometime in the next five years, however, Dixon became disillusioned with the church, and he began to believe that he could no longer belong to any particular denomination. In 1895, Dixon resigned from the Baptist ministry, and started preaching at a nondenominational church. He continued preaching there until 1899, when he began to lecture fulltime.

Dixon enjoyed lecturing and was often hailed as the best lecturer in the nation.[20] He gained an immense following throughout the country, particularly in the South, where he played up his speeches on the plight of the working man and what he called the horrors of Reconstruction.[21]

It was during such a lecture tour that Dixon attended a theatrical version of Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin. Dixon could hardly contain his anger and outrage at the play, and it is said that he literally "wept at [the play's] misrepresentation of southerners."[22] Dixon vowed that the "true story" of the South should be told. As a direct result from that experience, Dixon wrote his first novel, The Leopard's Spots (1902), which uses several characters, including Simon Legree, recycled from Stowe's novel.[20]

Writings and film adaptations

| "I thank God that there is not to-day the clang of a single slave's chain in this continent. Slavery may have had its beneficent aspects, but democracy is the destiny of the race, because all men are bound together in the bonds of fraternal equality with common love."

-Thomas Dixon Jr., 1896 from Protestantism and Its Causes, New York[6] |

"...no amount of education of any kind, industrial, classical or religious, can make a Negro a white man or bridge the chasm of centuries which separate him from the white man in the evolution of human nature."

-Thomas Dixon Jr., 1905 from "Booker T. Washington and the Negro", p. 1, Saturday Evening Post, August 19, 1905.[23] |

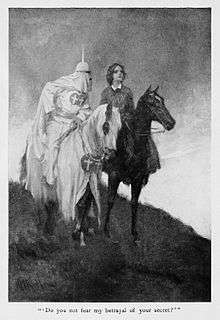

Dixon's "Trilogy of Reconstruction" consisted of The Leopard's Spots (1902), The Clansman (1905), and The Traitor (1907). Dixon's novels were best-sellers in their day, despite being sordid racist parodies of historical romance fiction. They glorify a antebellum American South white supremacist viewpoint. Dixon claimed to oppose slavery, but he espoused racial segregation and vehemently opposed universal suffrage and miscegenation.[24]

Dixon's Reconstruction era novels depict Northerners as greedy carpetbaggers and white Southerners as victims. Their prejudice and bigotry appealed to a readership that feared losing its privileged legacy of brutal oppression and exploitation.[25] Dixon's "Clansman" caricatures the Reconstruction as an era of "black rapists" and "blonde-haired" victims, and if his racist views were unknown, the vile and gratuitous brutality and Klan terror in which the novel revels would be read as satire.[25] If "Dixon used the motion picture as a propaganda tool for his often outrageous opinions on race, communism, socialism, and feminism,"[26] D. W. Griffith in his film adaptation of the novel, The Birth of a Nation (1915) was a case in point. Dixon wrote a stage adaptation of The Clansman in 1905. In The Leopard's Spots, the Reverend Durham character indoctrinates Charles Gaston, the protagonist with a foulmouthed diatribe of hate speech.[25] One critic notes that the term for marriage "the Holy of Holies" may be a crude euphemism for vagina.[25] Equally Dixon's opposition to miscegenation was as much confused sexism as racism, as he opposed white woman and black man relationships but not black woman and white man relationships.[25]

Another pet- hate for Dixon and the focus of his trilogy was socialism: The One Woman: A Story of Modern Utopia (1903), Comrades: A Story of Social Adventure in California (1909), and The Root of Evil (1911), which also discusses some of the problems involved in modern industrial capitalism. The book Comrades was made into a motion picture entitled Bolshevism on Trial released in 1919. In the play, The Sins of the Father, which was produced in 1910–1911, Dixon himself took the leading role.

Dixon authored 22 novels and he wrote many plays, sermons, and works of nonfiction. His writing mostly centered on three major themes: racial purity, the evils of socialism, and the traditional family role of women as wife/mother.[27] A common theme found in his novels is violence against white woman, mostly by Southern black men. The crimes are almost always avenged through the course of the story, the source of which might stem from a belief of Dixon that his mother had been sexually abused as a child.[28] He wrote his last novel, The Flaming Sword, in 1939 and not long after was crippled by a cerebral hemorrhage.[29]

Attitudes toward revived Klan

Dixon was an extreme nationalist, chauvinist, xenophobic, racist, reactionary ideologue, but he distanced himself from the "bigotry" of the revived second era Ku Klux Klan seems that he inferred that the "Reconstruction Klan" members were not bigots. He denounced antisemitism as "idiocy", but only on the grounds that the mother of Jesus was Jewish. While lauding the "loyalty and good citizenship" of Catholics, he claimed it was the "duty of whites to lift up and help" the supposedly "weaker races." His ultimate intent was to promote aggressive far-right politics.[30]

Family

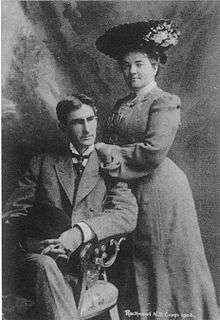

Dixon married his first wife, Harriet Bussey, on March 3, 1886. Both were forced to elope to Montgomery, Alabama, after Bussey's father refused to give his consent.[31] l

Dixon and Harriet Bussey had three children together: Thomas III, Louise, and Gordon. After a career of major ups and downs that saw Dixon earn and lose millions, he ended his career as a court clerk in Raleigh, North Carolina.[32] Harriet died on 29 December 1937, and fourteen months later, on February 26, 1939, Dixon suffered a crippling cerebral hemorrhage.[33] Less than a month later, from his hospital bed, Dixon married Madelyn Donovan, an actress who had played a role in a film adaptation of one of his novels.[33]

Later life

Dixon is buried with Madelyn in Sunset Cemetery in Shelby, North Carolina. His gravestone reads, "Thomas Dixon Jr. 1864-1946 Lawyer-Minister-Author-Orator-Playwright-Actor A Native of Cleveland County and Most Distinguished Son of His Generation. -- He was the author of 28 books dealing with the reconstruction period. The most popular of which were 'The Clansman' and 'The Leopard's Spots,' from which 'The Birth of a Nation' was dramatized. -- His Wife Madelyn Donovan 1894-1975."[34]

His brother, preacher Amzi Clarence Dixon, helped to edit The Fundamentals, a series of articles (and later volumes) influential in fundamentalist Christianity.

Thomas Dixon Collection

The Thomas Dixon Collection of over fifteen hundred volumes from Dixon's personal book collection and nine paintings featuring illustrations from his novels is hosted by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Gardner-Webb University in Boiling Springs, North Carolina.[35][36]

List of works

- The Leopard's Spots (1902) (Part 1 of the trilogy)

- The One Woman: A Story of Modern Utopia (1903)

- The Clansman (1905) (Part 2 of the trilogy)

- The Life Worth Living: A Personal Experience (1905)

- The Traitor: A Story of the Fall of the Invisible Empire (1907) (Part 3 of the trilogy)

- Comrades: A Story of Social Adventure in California (1909)

- The Root of Evil (1911)

- The Sins of the Father: A Romance of the South (1912)

- The Southerner: A Romance of the Real Lincoln (1913)

- The Victim: A Romance of the Real Jefferson Davis (1914)

- The Foolish Virgin: A Romance of Today (1915)

- The Fall of a Nation (1916)

- The Way of a Man (1918)

- Bolshevism on Trial" - movie (1919)

- A Man of the People (1920)

- The Man in Gray (1921)

- The Mark of the Beast (1923) produced and directed[37]

- The Love Complex (1925)

- The Sun Virgin (1929)

- Nation Aflame - screenplay (1937)

- The Flaming Sword (1939)

References

- Notes

- ↑ Maxwell Bloomfield, "Dixon's 'The Leopard's Spots': A Study in Popular Racism." American Quarterly 16.3 (1964): 387-401. online

- ↑ Cook, Thomas Dixon pp. 21-22; Gillespie, Thomas Dixon Jr. and the Birth of Modern America.

- ↑ Cook, Thomas Dixon, p. 23; Gillespie, Thomas Dixon Jr. and the Birth of Modern America.

- ↑ Cook, Thomas Dixon, pp. 22-27.

- ↑ Cook, Thomas Dixon, p. 23.

- 1 2 3 Roberts, p. 202.

- ↑ Cook, Thomas Dixon, p. 25; Gillespie, Thomas Dixon Jr. and the Birth of Modern America

- ↑ Cook, Thomas Dixon, p. 34.

- ↑ "History and catalogue of the Kappa Alpha fraternity". Kappa Alpha Order, Chi Chapter. 1891: 228.

- ↑ Cook, Thomas Dixon, p. 34; Gillespie, Thomas Dixon Jr. and the Birth of Modern America; Williamson, A Rage for Order: Black-White Relations in the American South Since Emancipation

- ↑ Gillespie, Thomas Dixon Jr. and the Birth of Modern America; Slide, American Racist: The Life and Films of Thomas Dixon.

- ↑ Gillespie, Thomas Dixon Jr. and the Birth of Modern America.

- ↑ "Dixon, Thomas". American National Biography. Retrieved March 13, 2017.

Dixon now decided that he would try politics, and in 1884 he ran successfully for a Democratic seat in the state legislature.

- ↑ Cook, Thomas Dixon, p. 36; Gillespie, Thomas Dixon Jr. and the Birth of Modern America

- ↑ Cook, Thomas Dixon, p. 38.

- ↑ Cook, Thomas Dixon, pp. 38-39.

- 1 2 Cook, Thomas Dixon, p. 40.

- 1 2 Cook, Thomas Dixon, p. 41.

- 1 2 Cook, Thomas Dixon, p. 42.

- 1 2 Cook, Thomas Dixon, p. 51; Slide, p. 25.

- ↑ Slide, American Racist: The Life and Films of Thomas Dixon.

- ↑ Slide, p. 25.

- ↑ Roberts, p. 204.

- ↑ Gillespie, Thomas Dixon Jr. and the Birth of Modern America; Slide, American Racist: The Life and Films of Thomas Dixon, p. 27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Leiter, Andrew (2004). "Thomas Dixon, Jr.: Conflicts in History and Literature". Documenting the American South. Retrieved 2017-07-21.

- ↑ Slide, Anthony American Racist: The Life and Films of Thomas Dixon

- ↑ Cook, Raymond A. Fire from the Flint: The Amazing Careers of Thomas Dixon (1968)

- ↑ Slide, p. 30.

- ↑ Gillespie, Thomas Dixon Jr. and the Birth of Modern America; Davenport, F. Garvin. Journal of Southern History, August 1970.

- ↑ "Thomas Dixon Dies; Wrote 'Clansman'", New York Times, April 4, 1946, p. 23.

- ↑ Cook, Thomas Dixon, p. 39.

- ↑ Gillespie, Thomas Dixon Jr. and the Birth of Modern America; Davenport, Journal of Southern History: August 1970; New York Times, April 17, 1934. p. 19, Dixon Penniless; $1,250,000 Gone.

- 1 2 Cook, Thomas Dixon, p. 128.

- ↑ "Thomas Dixon's headstone at FindAGrave.com". Retrieved 2007-02-07.

- ↑ "Archives". Gardner-Webb University. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ↑ "Thomas Dixon Library Goes to Gardner-Webb College". The Daily Times-News. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ↑ Anthony Slide - American Racist: The Life and Films of Thomas Dixon 2004 Page 161 0813171911 " If The Mark of the Beast is important as the only film that Thomas Dixon directed as well as wrote and produced, it is equally important for bringing Madelyn Donovan openly into his life."

Public

- Bibliography

- Bloomfield, Maxwell. "Dixon's 'The Leopard's Spots': A Study in Popular Racism." American Quarterly 16.3 (1964): 387-401. online

- Cook, Raymond A. Thomas Dixon pp. 21–22, Twayne Publications, Inc., 1974. ISBN 0-8057-0206-7

- Gilmore, Glenda Elizabeth. Gender and Jim Crow: Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina, 1986-1920. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1996. ISBN 0-8078-2287-6

- Gillespie, Michele K. and Hall, Randal L. Thomas Dixon Jr. and the Birth of Modern America, Louisiana State University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-8071-3130-X

- Williamson, Joel. A Rage for Order: Black-White Relations in the American South Since Emancipation, Oxford, 1986. ISBN 0-19-504025-2

- Slide, Anthony, American Racist: The Life and Films of Thomas Dixon, University Press of Kentucky, 2004. ISBN 0-8131-2328-3

- Roberts, Samuel K. Kelly Miller and Thomas Dixon Jr. on Blacks in American Civilization, pp. 202–209, Phlyon, Vol. 41, No. 2 (2nd Quarter 1980)

- Davenport, F. Garvin Jr. Thomas Dixon's Mythology of Southern History, pp. 350–367, The Journal of Southern History, Vol. 36, No. 3 (August 1970)

- McGee, Brian R. "Thomas Dixon's The Clansman: Radicals, Reactionaries, and the Anticipated Utopia", pp. 300–317, Southern Communication Journal, Vol. 65 (2000)

- McGee, Brian R. "The Argument from Definition Revised: Race and Definition in the Progressive Era", pp. 141–158, Argumentation and Advocacy, Vol. 35 (1999)

Sources

- Lehr, Dick (2014), The Birth of a Nation: How a Legendary Director and a Crusading Editor Reignited America's Civil War, New York, Public Affairs.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thomas Dixon Jr.. |

- Historical Information from Historical Marker Database

- Dixon and his novels

- Works by Thomas Dixon Jr. at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Thomas Dixon at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Thomas Dixon Jr. at Internet Archive

- Works by Thomas Dixon Jr. at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Thomas Dixon Jr. at Find a Grave

- Full version of The Clansman

- Thomas F. Dixon Jr. on IMDb

- Thomas Frederick Dixon Jr. Collection at Gardner-Webb University

- Thomas Frederick Dixon, Jr. Collection: Finding Aid