New Orleans massacre of 1866

| New Orleans Massacre | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Reconstruction Era | |||

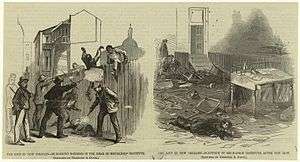

The massacre in New Orleans – murdering negroes in the rear of Mechanics' Institute ; Platform in Mechanics' Institute after the riot, Harper's Weekly, 1866 | |||

| Date | July 30, 1866 | ||

| Location | New Orleans, Louisiana | ||

| Caused by | Louisiana State Constitutional Convention | ||

| Resulted in | Martial law declared | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

| |||

| Casualties | |||

| |||

The New Orleans Massacre of 1866 occurred on July 30, during a violent conflict as white Democrats including police and firemen attacked Republicans, most of them African American, parading outside the Mechanics Institute in New Orleans. It was the site of a reconvened Louisiana Constitutional Convention. The Republicans in Louisiana had called for the Convention, as they were angered by the legislature's enactment of the Black Codes and its refusal to give black men the vote. Democrats considered the reconvened convention to be illegal and were suspicious of Republican attempts to increase their political power in the state. The riot "stemmed from deeply rooted political, social, and economic causes,"[2] and took place in part because of the battle "between two opposing factions for power and office."[2] There were a total of 150 black casualties, including 44 killed. In addition, three white Republicans were killed, as was one white protester.[3]

During much of the American Civil War, New Orleans had been occupied and under martial law imposed by the Union. On May 12, 1866, Mayor John T. Monroe was reinstated as acting mayor, the position he held before the war. Judge R. K. Howell was elected as chairman of the convention, with the goal of increasing participation by voters likely to vote Republican.[4]

The riot expressed conflicts deeply rooted within the social structure of Louisiana. It was a continuation of the war: more than half of the whites were Confederate veterans, and nearly half of the blacks were veterans of the Union army. The national reaction of outrage at the Memphis riots of 1866 and this riot nearly three months later led to Republicans gaining a majority in the United States House of Representatives and the Senate in the 1866 election. The riots catalyzed support for the Fourteenth Amendment, extending suffrage and full citizenship to freedmen, and the Reconstruction Act, to establish military districts for the national government to oversee areas of the South and work to change their social arrangements.

Tension builds

The state Constitutional Convention of 1864 authorized greater civil freedoms to blacks within Louisiana, but did not provide for voting rights for any people of color. Free people of color, who were mixed-race, had been an important part of New Orleans for more than a century and were established as a separate class in the colonial period, before United States annexation of the territory in 1803. Many were educated and owned property, and were seeking the vote. In addition, Republicans had the goals of extending the suffrage to freedmen and eliminating the Black Codes passed by the legislature. They reconvened the convention, and succeeded in incorporating these goals.[5]

Democrats considered the reconvened convention illegal, as they said that the voters (although then limited to whites only) had accepted the constitution. In addition, they argued legal technicalities: the elected chairman Howell had left the original convention before its conclusion and was therefore was not considered a member, the constitution was accepted by the people, and the radicals, only 25 of whom were present at the convention of 1864, did not make up a majority of the original convention.

On July 27, the black supporters of the convention, including approximately 200 black war veterans, met at the steps of the Mechanics Institute. They were stirred by speeches of abolitionist activists, most notably Anthony Paul Dostie and former Governor of Louisiana Michael Hahn. The men proposed a parade to the Mechanics Institute on the day of the convention to show their support.

The massacre

The convention met at noon on July 30, but a lack of a quorum caused postponement to 1:30.[6] When the convention members left the building, they were met by the black marchers with their marching band. On the corner of Common and Dryades streets, across from the Mechanics Institute, a group of armed whites awaited the black marchers.[7] This group was composed of Democrats who opposed abolition; most were ex-Confederates who wanted to disrupt the convention and the threat of the increasing political and economic power of blacks in the state.

It is not known which group fired first, but within minutes, there was a battle in the streets. The black marchers were unprepared and many were unarmed; they rapidly dispersed, with many seeking refuge within the Mechanics Institute. The white mob brutally attacked blacks on the street and some entered the building:

The whites stomped, kicked, and clubbed the black marchers mercilessly. Policemen smashed the institute’s windows and fired into it indiscriminately until the floor grew slick with blood. They emptied their revolvers on the convention delegates, who desperately sought to escape. Some leapt from windows and were shot dead when they landed. Those lying wounded on the ground were stabbed repeatedly, their skulls bashed in with brickbats. The sadism was so wanton that men who kneeled and prayed for mercy were killed instantly, while dead bodies were stabbed and mutilated.

— Ron Chernow, "Grant" (2017)[8]

Federal troops responded to suppress the riot, and jailed many of the white insurgents. The governor declared the city under martial law until August 3.

Approximately 50 people were killed, including Victor Lacroix.

National reaction: a Republican Congress

The national reaction to the New Orleans riot and to the earlier Memphis riots of 1866, was one of heightened concern about the current Reconstruction strategy and desire for a change of leadership. In the 1866 House of Representatives and Senate elections, the Republicans won in a landslide, gaining 77% of the seats in Congress.[9]

Early in 1867, the First Reconstruction Act was passed – over the President's veto[10] – to provide for more federal control in the South. Military districts were created to govern the region until violence could be suppressed and a more democratic political system established. Under the act, Louisiana was assigned to the Fifth Military District. Ex-Confederates, mostly white Democrats, were temporarily disenfranchised, and the right of suffrage was to be enforced for free people of color. Politicians associated with the riot were dismissed from office.

See also

References

- Notes

- ↑ New Orleans Massacre (1866)

- 1 2 Vandal (1984), p. 137.

- ↑ Bell, Caryn Cossé (1997). Revolution, Romanticism, and the Afro-Creole Protest Culture in Louisiana 1718-1868. Baton Rouge, La.: LSU Press. p. 262.

- ↑ Kendall (1992), p. 305.

- ↑ Kendall (1992), p. 308.

- ↑ Bell (1997), p. 261.

- ↑ Kendall (1992), p. 312.

- ↑ Chernow (2017), pp. 574-575.

- ↑ Radcliff (2009), pp. 12-16.

- ↑ Johnson, Andrew. "Veto for the first Reconstruction Act March 2, 1867 To the house of Representatives:". American History: From Revolution to Reconstruction and beyond... University of Groningen. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- Bibliography

- Bell, Caryn Cossé (1997). Revolution, Romanticism, and the Afro-Creole Protest Tradition in Louisiana 1718-1868. Baton-Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

- Chernow, Ron (2017). Grant. Penguin.

- Fortier, Alcée (1904). A History of Louisiana, Volume 4, Part 2. Paris: Goupil and Company.

- Hollandsworth, James G. (2004). An Absolute Massacre: The New Orleans Race Riot of July 30, 1866. Louisiana State University Press.

- Kendall, John (1922). "The Riot of 1866". History of New Orleans. Chicago: The Lewis Publishing Company.

- McPherson, Edward (1875). The Political History of the United States of America During the Period of Reconstruction. Washington, D.C.: Solomans and Chapman.

- Radcliff, Michael A. (2009). The Custom House Conspiracy. New Orleans: Crescent City Literary Classics.

- Reed, Emily Hazen (1868). Life of A. P. Dostie, Or, The Conflict in New Orleans. New York: W.P. Tomlinson.

- Riddleberger, Patrick W. (1979). 1866, The Critical Year Revisited. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

- Trefousse, Hans L. (1999). "Andrew Johnson". American National Biography. 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Vandal, Gilles (1984). The New Orleans Riot of 1866: Anatomy of a Tragedy. Center for Louisiana Studies.

- Wainwright, Irene. Administrations of the Mayor's of New Orleans: Monroe. Louisiana Division New Orleans Public Library. Retrieved February 4, 2007.

External links

- "New Orleans Race Riot". Center for History and New Media, George Mason University. 2002.

- "The New Orleans Massacre". Harper's Weekly. March 30, 1867. p. 202.