Chief Justice of the United States

| Chief Justice of the United States | |

|---|---|

Seal of the U.S. Supreme Court | |

|

United States Supreme Court Federal judiciary of the United States | |

| Style |

Mr. Chief Justice (informal) Your Honor (when addressed in court) The Honorable (formal) |

| Status |

Chief Justice Head of a court system Highest judicial officer |

| Member of |

Supreme Court Judicial Conference Administrative Office of the Courts |

| Seat | Supreme Court Building, Washington, D.C. |

| Appointer |

The President with Senate advice and consent |

| Term length | Life tenure |

| Constituting instrument | United States Constitution |

| Formation | March 4, 1789 |

| First holder |

John Jay as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court (September 26, 1789) |

| Website |

www |

| This article is part of the series on the |

| United States Supreme Court |

|---|

|

| The Court |

| Current membership |

| All members |

| Court functionaries |

|

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of the United States of America |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

The Chief Justice of the United States is the chief judge of the nine-member Supreme Court of the United States, the highest judicial body in the United States. As such, the chief justice is the highest-ranking judge of the federal judiciary—one of the three branches of the federal government. Article II, Section 2, Clause 2 of the Constitution grants plenary power to the President of the United States to nominate, and with the advice and consent (confirmation) of the United States Senate, appoint a chief justice, who serves until they resign, are impeached and convicted, retire, or die.

The Chief Justice has significant influence in the selection of cases for review, presides when oral arguments are held, and leads the discussion of cases among the justices. Additionally, when the Court renders an opinion, the chief justice—if in the majority—chooses who writes the Court's opinion. When deciding a case, however, the chief justice's vote counts no more than that of any associate justice.

Article I, Section 3, Clause 6 of the Constitution designates the chief justice to preside during presidential impeachment trials in the Senate; this has occurred twice. Also, while nowhere mandated, the presidential oath of office is typically administered by the Chief Justice.

Additionally, the Chief Justice serves as a spokesperson for the federal government's judicial branch and acts as a chief administrative officer for the federal courts. The Chief Justice presides over the Judicial Conference and, in that capacity, appoints the director and deputy director of the Administrative Office. The Chief Justice is also an ex officio member of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution and, by custom, is elected chancellor of the board.

Since the Supreme Court was established in 1789, 17 people have served as chief justice. The first was John Jay (1789–1795). The current chief justice is John Roberts (since 2005). Four—Edward Douglass White, Charles Evans Hughes, Harlan Fiske Stone, and William Rehnquist—were previously confirmed for associate justice and subsequently confirmed for chief justice separately.

Origin, title, and appointment to office

The United States Constitution does not explicitly establish an office of Chief Justice, but presupposes its existence with a single reference in Article I, Section 3, Clause 6: "When the President of the United States is tried, the Chief Justice shall preside." Nothing more is said in the Constitution regarding the office. Article III, Section 1, which authorizes the establishment of the Supreme Court, refers to all members of the Court simply as "judges". The Judiciary Act of 1789 created the distinctive titles of Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States and Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.

In 1866, at the urging of Salmon P. Chase, Congress restyled the chief justice's title to the current Chief Justice of the United States. The first person whose Supreme Court commission contained the modified title was Melville Fuller in 1888.[1] The associate justices' title was not altered in 1866, and remains as originally created.

The chief justice, like all federal judges, is nominated by the President and confirmed to office by the U.S. Senate. Article III, Section 1 of the Constitution specifies that they "shall hold their Offices during good Behavior". This language means that the appointments are effectively for life, and that, once in office, justices' tenure ends only when they die, retire, resign, or are removed from office through the impeachment process. Since 1789, 15 presidents have made a total of 22 official nominations to the position.[2]

The salary of the chief justice is set by Congress; the current (2018) annual salary is $267,000, which is slightly higher than that of associate justices, which is $255,300.[3]

The practice of appointing an individual to serve as chief justice is grounded in tradition; while the Constitution mandates that there be a chief justice, it is silent on the subject of how one is chosen and by whom. There is no specific constitutional prohibition against using another method to select the chief justice from among those justices properly appointed and confirmed to the Supreme Court. Constitutional law scholar Todd Pettys has proposed that presidential appointment of chief justices should be done away with, and replaced by a process that permits the Justices to select their own chief justice.[4]

Three incumbent associate justices have been nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate as chief justice: Edward Douglass White in 1910, Harlan Fiske Stone in 1941, and William Rehnquist in 1986. A fourth, Abe Fortas, was nominated to the position in 1968, but was not confirmed. As an associate justice does not have to resign his or her seat on the Court in order to be nominated as chief justice, Fortas remained an associate justice. Similarly, when associate justice William Cushing was nominated and confirmed as chief justice in January 1796, but declined the office, he too remained on the Court. Two former associate justices subsequently returned to service on the Court as chief justice. John Rutledge was the first. President Washington gave him a recess appointment in 1795. However, his subsequent nomination to the office was not confirmed by the Senate, and he left office and the Court. In 1933, former associate justice Charles Evans Hughes was confirmed as chief justice. Additionally, in December 1800, former chief justice John Jay was nominated and confirmed to the position a second time, but ultimately declined it, opening the way for the appointment of John Marshall.[2]

Duties

Along with his general responsibilities as a member of the Supreme Court, the Chief Justice has several unique duties to fulfill.

Impeachment trials

Article I, section 3 of the U.S. Constitution stipulates that the Chief Justice shall preside over impeachment trials of the President of the United States in the U.S. Senate. Two Chief Justices, Salmon P. Chase and William Rehnquist, have presided over the trial in the Senate that follows an impeachment of the president – Chase in 1868 over the proceedings against President Andrew Johnson and Rehnquist in 1999 over the proceedings against President Bill Clinton. Both presidents were subsequently acquitted.

Seniority

Many of the procedures and inner workings of the Court turn on the seniority of the justices. Traditionally, the chief justice has been regarded as primus inter pares (first among equals)—that is, the chief justice is the highest-ranking and foremost member of the Court, regardless of that officeholder's length of service when compared against that of any associate justice. This seniority and added prestige enables a chief justice to define the Court's culture and norms and, thus, influence how it functions. The chief justice sets the agenda for the weekly meetings where the justices review the petitions for certiorari, to decide whether to hear or deny each case. The Supreme Court agrees to hear less than one percent of the cases petitioned to it. While associate justices may append items to the weekly agenda, in practice this initial agenda-setting power of the chief justice has significant influence over the direction of the court. Nonetheless, a chief justice's influence may be limited by circumstances and the associate justices' understanding of legal principles; it is definitely limited by the fact that he has only a single vote of nine on the decision whether to grant or deny certiorari.[5][6]

Despite the chief justice's elevated stature, his vote carries the same legal weight as the vote of each associate justice. Additionally, he has no legal authority to overrule the verdicts or interpretations of the other eight judges or tamper with them.[5] The task of assigning who shall write the opinion for the majority falls to the most senior justice in the majority. Thus, when the chief justice is in the majority, he always assigns the opinion.[7] Early in his tenure, Chief Justice John Marshall insisted upon holdings which the justices could unanimously back as a means to establish and build the Court's national prestige. In doing so, Marshall would often write the opinions himself, and actively discouraged dissenting opinions. Associate Justice William Johnson eventually persuaded Marshall and the rest of the Court to adopt its present practice: one justice writes an opinion for the majority, and the rest are free to write their own separate opinions or not, whether concurring or dissenting.[8]

The chief justice's formal prerogative—when in the majority—to assign which justice will write the Court's opinion is perhaps his most influential power,[6] as this enables him to influence the historical record.[5] He "may assign this task to the individual justice best able to hold together a fragile coalition, to an ideologically amenable colleague, or to himself." Opinion authors can have a big influence on the content of an opinion; two justices in the same majority, given the opportunity, might write very different majority opinions.[6] A chief justice who knows well the associate justices can therefore do much—by the simple act of selecting the justice who writes the opinion of the court—to affect the general character or tone of an opinion, which in turn can affect the interpretation of that opinion in cases before lower courts in the years to come.

Additionally, the chief justice chairs the conferences where cases are discussed and tentatively voted on by the justices. He normally speaks first and so has influence in framing the discussion. Although the chief justice votes first—the Court votes in order of seniority—he may strategically pass in order to ensure membership in the majority if desired.[6] It is reported that:

Chief Justice Warren Burger was renowned, and even vilified in some quarters, for voting strategically during conference discussions on the Supreme Court in order to control the Court’s agenda through opinion assignment. Indeed, Burger is said to have often changed votes to join the majority coalition, cast "phony votes" by voting against his preferred position, and declined to express a position at conference.[9]

Oath of office

The Chief Justice typically administers the oath of office at the inauguration of the President of the United States. This is a tradition, rather than a constitutional responsibility of the Chief Justice; the Constitution does not require that the oath be administered by anyone in particular, simply that it be taken by the president. Law empowers any federal and state judge, as well as notaries public (such as John Calvin Coolidge, Sr.), to administer oaths and affirmations.

If the Chief Justice is ill or incapacitated, the oath is usually administered by the next senior member of the Supreme Court. Seven times, someone other than the Chief Justice of the United States administered the oath of office to the President.[10] Robert Livingston, as Chancellor of the State of New York (the state's highest ranking judicial office), administered the oath of office to George Washington at his first inauguration; there was no Chief Justice of the United States, nor any other federal judge prior to their appointments by President Washington in the months following his inauguration. William Cushing, an associate justice of the Supreme Court, administered Washington's second oath of office in 1793. Calvin Coolidge's father, a notary public, administered the oath to his son after the death of Warren Harding.[11] This, however, was contested upon Coolidge's return to Washington and his oath was re-administered by Judge Adolph A. Hoehling, Jr. of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia.[12] John Tyler and Millard Fillmore were both sworn in on the death of their predecessors by Chief Justice William Cranch of the Circuit Court of the District of Columbia.[13] Chester A. Arthur and Theodore Roosevelt's initial oaths reflected the unexpected nature of their taking office. On November 22, 1963, after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Judge Sarah T. Hughes, a federal district court judge of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas, administered the oath of office to then Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson aboard the presidential airplane.

In addition, the Chief Justice ordinarily administers the oath of office to newly appointed and confirmed associate justices, whereas the senior associate justice will normally swear in a new Chief Justice or vice president.

Other duties

Since the tenure of William Howard Taft, the office of the Chief Justice has moved beyond just first among equals.[14] The Chief Justice also:

- Serves as the head of the federal judiciary.

- Serves as the head of the Judicial Conference of the United States, the chief administrative body of the United States federal courts. The Judicial Conference is empowered by the Rules Enabling Act to propose rules, which are then promulgated by the Supreme Court (subject to disapproval by Congress under the Congressional Review Act), to ensure the smooth operation of the federal courts. Major portions of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and Federal Rules of Evidence have been adopted by most state legislatures and are considered canonical by American law schools.

- Appoints sitting federal judges to the membership of the United States Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC), a "secret court" which oversees requests for surveillance warrants by federal police agencies (primarily the F.B.I.) against suspected foreign intelligence agents inside the United States. (see 50 U.S.C. § 1803).

- Appoints the members of the Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation, a special tribunal of seven sitting federal judges responsible for selecting the venue for coordinated pretrial proceedings in situations where multiple related federal actions have been filed in different judicial districts.

- Serves ex officio as a member of the Board of Regents, and by custom as the Chancellor, of the Smithsonian Institution.

- Supervises the acquisition of books for the Law Library of the Library of Congress.[15]

Unlike Senators and Representatives who are constitutionally prohibited from holding any other "office of trust or profit" of the United States or of any state while holding their congressional seats, the Chief Justice and the other members of the federal judiciary are not barred from serving in other positions. Chief Justice John Jay served as a diplomat to negotiate the so-called Jay Treaty (also known as the Treaty of London of 1794), Justice Robert H. Jackson was appointed by President Truman to be the U.S. Prosecutor in the Nuremberg trials of leading Nazis, and Chief Justice Earl Warren chaired The President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy. As described above, the Chief Justice holds office in the Smithsonian Institution and the Library of Congress.

Disability or vacancy

Under 28 USC,[16] when the Chief Justice is unable to discharge his functions, or that office is vacant, the duties are carried out by the most senior associate justice who is able to act, until the disability or vacancy ends, as chief justice.[4] Clarence Thomas is the most senior associate justice.

List of Chief Justices

Since the Supreme Court was established in 1789, the following 17 persons have served as Chief Justice:[17][18]

| Chief Justice | Date confirmed (Vote) |

Tenure[lower-alpha 1] | Tenure length | Appointed by | Prior position[lower-alpha 2] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

John Jay (1745–1829) |

September 26, 1789 (Acclamation) |

October 19, 1789 – June 29, 1795 (Resigned) |

5 years, 253 days | George Washington | Acting United States Secretary of State (1789–1790) |

| 2 |  |

John Rutledge (1739–1800) |

December 15, 1795 (10–14)[lower-alpha 3] |

August 12, 1795[lower-alpha 4] – December 28, 1795 (Resigned, nomination having been rejected) |

138 days | Chief Justice of the South Carolina Court of Common Pleas and Sessions (1791–1795) Associate Justice of the Supreme Court (1789–1791) | |

| 3 |  |

Oliver Ellsworth (1745–1807) |

March 4, 1796 (21–1) |

March 8, 1796 – December 15, 1800 (Resigned) |

4 years, 282 days | United States Senator from Connecticut (1789–1796) | |

| 4 |  |

John Marshall (1755–1835) |

January 27, 1801 (Acclamation) |

February 4, 1801 – July 6, 1835 (Died) |

34 years, 152 days | John Adams | 4th United States Secretary of State (1800–1801) |

| 5 |  |

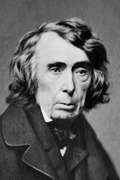

Roger B. Taney (1777–1864) |

March 15, 1836 (29–15) |

March 28, 1836 – October 12, 1864 (Died) |

28 years, 198 days | Andrew Jackson | 12th United States Secretary of the Treasury (1833–1834) |

| 6 |  |

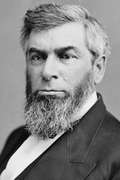

Salmon P. Chase (1808–1873) |

December 6, 1864 (Acclamation) |

December 15, 1864 – May 7, 1873 (Died) |

8 years, 143 days | Abraham Lincoln | 25th United States Secretary of the Treasury (1861–1864) |

| 7 |  |

Morrison Waite (1816–1888) |

January 21, 1874 (63–0) |

March 4, 1874 – March 23, 1888 (Died) |

14 years, 19 days | Ulysses S. Grant | Ohio State Senator (1849–1850) Presiding officer, Ohio constitutional convention (1873) |

| 8 |  |

Melville Fuller (1833–1910) |

July 20, 1888 (41–20) |

October 8, 1888 – July 4, 1910 (Died) |

21 years, 269 days | Grover Cleveland | President, Illinois State Bar Association (1886) Illinois State Representative (1863–1865) |

| 9 |  |

Edward Douglass White (1845–1921) |

December 12, 1910[lower-alpha 5] (Acclamation) |

December 19, 1910 – May 19, 1921 (Died) |

10 years, 151 days | William Howard Taft | Associate Justice of the Supreme Court (1894–1910) |

| 10 |  |

William Howard Taft (1857–1930) |

June 30, 1921 (Acclamation) |

July 11, 1921 – February 3, 1930 (Retired) |

8 years, 207 days | Warren G. Harding | 27th President of the United States (1909–1913) |

| 11 |  |

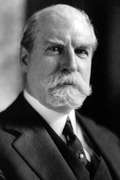

Charles Evans Hughes (1862–1948) |

February 13, 1930 (52–26) |

February 24, 1930 – June 30, 1941 (Retired) |

11 years, 126 days | Herbert Hoover | 44th United States Secretary of State (1921–1925) Associate Justice of the Supreme Court (1910–1916) |

| 12 |  |

Harlan F. Stone (1872–1946) |

June 27, 1941[lower-alpha 5] (Acclamation) |

July 3, 1941 – April 22, 1946 (Died) |

4 years, 293 days | Franklin D. Roosevelt | Associate Justice of the Supreme Court (1925–1941) |

| 13 |  |

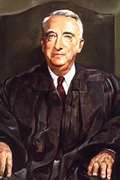

Fred M. Vinson (1890–1953) |

June 20, 1946 (Acclamation) |

June 24, 1946 – September 8, 1953 (Died) |

7 years, 76 days | Harry S. Truman | 53rd United States Secretary of the Treasury (1945–1946) |

| 14 |  |

Earl Warren (1891–1974) |

March 1, 1954 (Acclamation) |

October 5, 1953[lower-alpha 4] – June 23, 1969 (Retired) |

15 years, 261 days | Dwight D. Eisenhower | 30th Governor of California (1943–1953) |

| 15 |  |

Warren E. Burger (1907–1995) |

June 9, 1969 (74–3) |

June 23, 1969 – September 26, 1986 (Retired) |

17 years, 95 days | Richard Nixon | Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit (1956–1969) |

| 16 |  |

William Rehnquist (1924–2005) |

September 17, 1986[lower-alpha 5] (65–33) |

September 26, 1986 – September 3, 2005 (Died) |

18 years, 342 days | Ronald Reagan | Associate Justice of the Supreme Court (1972–1986) |

| 17 |  |

John Roberts (born 1955) |

September 29, 2005 (78–22) |

September 29, 2005 – Incumbent |

13 years, 14 days | George W. Bush | Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit (2003–2005) |

Notes

- ↑ The start date given here for each chief justice is the day they took the oath of office, and the end date is the day of the justice's death, resignation, or retirement.

- ↑ Listed here (unless otherwise noted) is the position—either with a U.S. state or the federal government—held by the individual immediately prior to becoming Chief Justice of the United States.

- ↑ This was the first Supreme Court nomination to be rejected by the United States Senate. Rutledge remains the only "recess appointed" justice not to be subsequently confirmed by the Senate.

- 1 2 Recess appointment

- 1 2 3 Elevated from associate justice to chief justice while serving on the Supreme Court. The nomination of a sitting associate justice to be chief justice is subject to a separate confirmation process.

See also

References

- ↑ "Administrative Agencies: Office of the Chief Justice, 1789–present". Washington, D.C.: Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- 1 2 McMillion, Barry J.; Rutkus, Denis Steven (July 6, 2018). "Supreme Court Nominations, 1789 to 2017: Actions by the Senate, the Judiciary Committee, and the President" (PDF). fas.org (Federation of American Scientists). Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

- ↑ "Judicial Compensation". Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- 1 2 Pettys, Todd E. (2006). "Choosing a Chief Justice: Presidential Prerogative or a Job for the Court?". Journal of Law & Politics. The University of Iowa College of Law. 22 (3): 231–281. SSRN 958829.

- 1 2 3 "Judiciary". Ithaca, New York: Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Cross, Frank B.; Lindquist, Stefanie (June 2006). "The decisional significance of the Chief Justice" (PDF). University of Pennsylvania Law Review. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Law School. 154 (6): 1665–1707.

- ↑ O'Brien, David M. (2008). Storm Center: The Supreme Court in American Politics (8th ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. p. 267. ISBN 978-0-393-93218-8.

- ↑ O'Brien, David M. (2008). Storm Center: The Supreme Court in American Politics (8th ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-393-93218-8.

- ↑ Johnson, Timothy R.; Spriggs II, James F.; Wahlbeck, Paul J. (June 2005). "Passing and Strategic Voting on the U.S. Supreme Court". Law & Society Review. Law and Society Association, through Wiley. 39 (2): 349–377. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ↑ "Presidential Inaugurations: Presidential Oaths of Office". Memory.loc.gov. Retrieved June 21, 2015.

- ↑ "Excerpt from Coolidge's autobiography". Historicvermont.org. Retrieved May 15, 2010.

- ↑ "Prologue: Selected Articles". Archives.gov. Retrieved May 15, 2010.

- ↑ "Presidential Swearing-In Ceremony, Part 5 of 6". Inaugural.senate.gov. Archived from the original on February 3, 2011. Retrieved August 17, 2011.

- ↑ O'Brien, David M. (2008). Storm Center: The Supreme Court in American Politics (8th ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-393-93218-8.

- ↑ "Jefferson's Legacy: A Brief History of the Library of Congress". Library of Congress. March 6, 2006. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- ↑ "28 U.S. Code § 3 – Vacancy in office of Chief Justice; disability | LII / Legal Information Institute". Law.cornell.edu. Retrieved June 21, 2015.

- ↑ "U.S. Senate: Supreme Court Nominations: 1789–Present". www.senate.gov. Retrieved February 17, 2016.

- ↑ "Justices 1789 to Present". www.supremecourt.gov. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

Further reading

- Abraham, Henry J. (1992). Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506557-3.

- Cushman, Clare (2001). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1995 (2nd ed.). (Supreme Court Historical Society, Congressional Quarterly Books). ISBN 1-56802-126-7.

- Flanders, Henry. The Lives and Times of the Chief Justices of the United States Supreme Court. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1874 at Google Books.

- Frank, John P. (1995). Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L., eds. The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0-7910-1377-4.

- Hall, Kermit L., ed. (1992). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505835-6.

- Martin, Fenton S.; Goehlert, Robert U. (1990). The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Books. ISBN 0-87187-554-3.

- Urofsky, Melvin I. (1994). The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Garland Publishing. p. 590. ISBN 0-8153-1176-1.

External links

.jpg)