Poplar, London

Poplar is a district in London, England. It is part of the East End and within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, and about 5.5 miles (8.9 km) east of Charing Cross and contains part of Canary Wharf. Poplar includes Poplar Baths, Chrisp Street Market, Balfron Tower and known for being the foundering location of West Ham United F.C. and the British Empire.

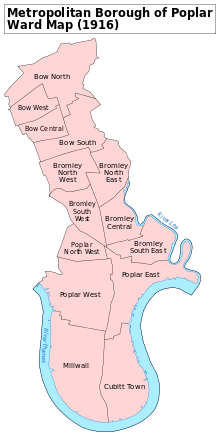

Originally part of the parish of Stepney, Middlesex, Poplar became a civil parish in 1817. In 1855, Poplar joined with neighbouring Bromley and Bow to form the Poplar District of the Metropolis. The district became the Metropolitan Borough of Poplar in 1900, and in 1965 merged with the Metropolitan Boroughs of Stepney and Bethnal Green to form the new London Borough of Tower Hamlets.

Geography

Architecturally it is a mixture of 18th and 19th-century terraced houses and 20th-century council estates with notable examples including the Lansbury Estate, the Balfron Tower and more recent developments including West India Quay.

History

Poplar was formerly part of the parish of Stepney and was first recorded in either 1327[1] or 1350.[2]

It took its name from the Black Poplar trees which once flourished in the area. Black Poplar is a very rare and exceptionally large tree that grows well in the wet conditions which the Thames and Lea historically brought to much of the neighbourhood. A specimen persisted in the area until at least 1986 when the naturalist Oliver Rackham noted "Nearby, in the midst of railway dereliction, a single Black Poplar even now struggles for life".[1]

In 1654, as the population of the hamlet began to grow, the East India Company ceded a piece of land upon which to build a chapel and this became the nucleus of the settlement.[3] St Matthias Old Church is located on Poplar High Street, opposite Tower Hamlets College.

In 1921, the Metropolitan Borough of Poplar was the location of the Poplar Rates Rebellion, led by then-Mayor George Lansbury, who was later elected as leader of the Labour Party. As part of the 1951 Festival of Britain, a new council housing estate was built to the north of the East India Dock Road and named the Lansbury Estate after him. This estate includes Chrisp Street Market, which was greatly commended by Lewis Mumford. The same era also saw the construction of the Robin Hood Gardens housing complex (overlooking the northern portal of the Blackwall Tunnel) – designed by architects Peter and Alison Smithson – and the similarly brutalist Balfron Tower, Carradale House and Glenkerry House (to the north) – designed by Ernő Goldfinger. Other notable buildings in Poplar include Poplar Baths, which reopened in 2016 having finally closed in 1988, after the efforts of local campaigners.

After West India Dock and Canary Wharf closed in 1980, the British Government adopted policies to redevelop of the southern Poplar as well as northern Millwall, including the creation of the London Docklands Development Corporation (LDDC) in 1981 and the granting of Urban Enterprise Zone status to the Isle of Dogs in 1982.

In 1998, following ballots of the residents, Tower Hamlets Council transferred parts of the Lansbury estate and six other Council housing estates within Poplar to Poplar HARCA, a new housing association set up for the purpose of regenerating the area. The following year, tenants on further estates voted to remain with the Council. However, after a lengthy consultation of all Council estates in Tower Hamlets begun in 2002, most estates in Poplar did transfer to Poplar HARCA, East End Homes and other landlords between 2005 and 2007.

Wartime bombings

Although many people associate wartime bombing with The Blitz during World War II, the first airborne terror campaign in Britain took place during the First World War. Air raids in World War I caused significant damage and took many lives. German raids on Britain, for example, caused 1,413 deaths and 3,409 injuries. Air raids provided an unprecedented means of striking at resources vital to an enemy's war effort. Many of the novel features of the war in the air between 1914 and 1918—the lighting restrictions and blackouts, the air raid warnings and the improvised shelters—became central aspects of the Second World War less than 30 years later.

The East End of London was one of the most heavily targeted places. Poplar, in particular, was struck badly by some of the air raids during the First World War. Initially these were at night by Zeppelins which bombed the area indiscriminately, leading to the death of innocent civilians.

The first daylight bombing attack on London by a fixed-wing aircraft took place on 13 June 1917. Fourteen German Gotha G bombers led by Hauptmann Ernst Brandenberg flew over Essex and began dropping their bombs. It was a hot day and the sky was hazy; nevertheless, onlookers in London's East End were able to see 'a dozen or so big aeroplanes scintillating like so many huge silver dragonflies'. These three-seater bombers were carrying shrapnel bombs which were dropped just before noon. Numerous bombs fell in rapid succession in various districts. In the East End alone 104 people were killed, 154 seriously injured and 269 slightly injured.

The gravest incident that day was a direct hit on a primary school in Poplar. In the Upper North Street School at the time were a girls' class on the top floor, a boys' class on the middle floor and an infant class of about 50 pupils on the ground floor. The bomb fell through the roof into the girls' class; it then proceeded to fall through the boys' classroom before finally exploding in the infant class. Eighteen pupils were killed, of whom sixteen were aged from 4 to 6 years old. The tragedy shocked the British public at the time.[4]

In World War II, Poplar suffered heavily in the Blitz of that war, the Metropolitan Borough losing 770 civilian dead as a result of enemy action.[5] At the height of the bombing, ten Poplar schools were evacuated to Oxford.[6]

Notable residents

- Teddy Baldock, "The Pride of Poplar", Commonwealth Boxing Bantamweight Champion 1928–30[7]

- Neil Banfield, coach at Arsenal F.C.

- Will Crooks MP, social reformer and first Labour Mayor in London; the Will Crooks estate on Poplar High Street is named after him

- Tommy Flowers, designer of the first programmable electronic computer used for code breaking at Bletchley park

- Sir Nicholas de Loveyne held the manor of Poplar and made his will there in 1375 four days before he died.

- John McDougall, politician, represented Poplar from 1889 to 1913. A small park near Millwall Dock is named after him.

- John Mucknell, "The King's Pirate" (born 1608, lived in Poplar after he married)[8]

- Harry Redknapp, football manager, formerly of Bournemouth, West Ham United, Southampton, Portsmouth, Tottenham Hotspur and Queens Park Rangers football clubs. Father of Jamie Redknapp, the former Liverpool captain

- Richard Spratly, discoverer of the Spratly Islands in 1843.

- H. M. Tomlinson, travel-writer, journalist, and author of The Sea and the Jungle (1912)

- Jennifer Worth, Call the Midwife author

In art, entertainment, and media

Balfron Tower has been featured in various other music videos, films and television programmes, as have various other locations in Poplar. According to movie website IMDb, locations around Poplar have been used in the following feature films:

- 1984 (1956)

- To Sir, With Love (1967)

- A Fish Called Wanda (1988)

- The World Is Not Enough (1999)

- The Da Vinci Code (2003)

- 28 Weeks Later (2007; Woodstock Terrace and Balfron Tower)

- Return of Spinal Tap (1992; Coldharbour) David and Nigel reminisce about their upbringing in 'Squatney, London', outside their childhood homes No.45 & 47. 'The Gun' public house can also be seen in the background.

Film

- The documentary film Fly a Flag for Poplar (1974) features Poplar and the people who live there, seen in their day-to-day lives and organising their own local festivals. Poplar today is looked at in the light of the past, the importance of the labour movement in the beginning of the century, highlighted by the great strikes and events of 1921 when the Poplar Council went to prison.[9]

- Madonna shot scenes in Poplar Baths for the film Shanghai Surprise (1986).

- A documentary film about Chrisp Street Market, E14: A Dying Trade, was filmed in 2011.[10]

Television

- The BBC One television series, Call the Midwife, is set in Poplar in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Art

- The AB Foundry is in Poplar[11] and has worked with artists like Anthony Gormley, Henry Moore, Gavin Turk, Rachel Whiteread, and Barry Flanagan.

- The Poplar Union was the first purposefully built as a fully-fledged art centre within a Poplar HARCA’s resident building. Poplar Union is now home to e5 Roasthouse, the new coffee roastery and café, run by the company behind e5 Bakehouse. It supports the local community through art, culture and wellbeing, and offer a diverse programme of events, including family activities, performances in comedy, spoken word, music, dance and theatre, health and wellbeing classes.[12][13]

- While not as famous as a street art destination as its Hackney Wick neighbour, Poplar has a number of notable street art pieces, especially around the Crisp Street Market area. American Artist Above, Malarky, Cawaiikawaii, Lilly Lou and Gary Stranger have all done work there, especially on the shop shutters.[14] Irony and Boe painted a giant chihuahua on the side of the building opposite All Saints DLR station.[15][16] There had been a Banksy next to the chihuahua but it is no longer there.[17]

- Notable artists that have lived in the area are Michael Green, Ian Berry, Elizabeth Fritsch MA(RCA) CBE and Stuart Semple, who all lived and worked in the Spratts complex [18][19] and many artists take up spaces in the Bow Arts Trust's spaces in Balfron Tower[20][21][22][23]

Landmarks

A new Church Green next to St. Mary and St. Joseph Church was created in 2012 on the site of the former Blitz-bombed Catholic church, across the road from the current church designed by Adrian Gilbert Scott. It is open to the public during the day and public sculptures include, the former Catholic Boys' School entrance statue dedicated to dockers and seafarers, a 15-foot crucifix that stood on the site of the old high altar and a contemporary granite and light sculpture, A Doorway of Hope, by sculptor Nicolas Moreton.[24]

Poplar High Street is host to a number of landmarks due to it previously being the principal street in Poplar,[25] including the Poplar Town Hall, which has mosaic detail and now a hotel[26] and Poplar Bowls Club, foundered in 1910 and is part of Poplar Recreation Ground[27] and a recently reopened sports centre called The Workhouse stands on the site of Poplar Workhouse,[28] where local politician Will Crooks spent some of his earliest years (a nearby council housing estate is named after him) and the designated Grade II* listed St Matthias Old Church, now a community centre and formally a chapel that was built by the East India Company in 1654.[29][30].

The original Poplar Baths opened in 1852, costing £10,000. It was built to provide public wash facilities for the East End's poor as a result of the Baths and Washhouses Act 1846. The Baths were rebuilt in 1933 to a design by Harley Heckford and the larger pool was covered over to convert the building into a theatre and designated the East India Hall. Poplar Baths reopened in 1947 after the Second World War and continued to be used as a swimming facility, attracting on average 225,700 bathers every year between 1954 and 1959, the Baths closed again and was conversion to an industrial training centre in 1988.[31] The Baths once again re-opened on 25 July 2016 and were removed from the Buildings at Risk register.[32][33]

The Museum of London Docklands in West India Quay, opened in 2003 on the site of a grade I listed early-19th century Georgian "low" sugar warehouses built in 1802 on the side of West India Docks in the Port of London.[34]

Education

Transport

Poplar is connected solely by the Docklands Light Railway (DLR) and has four stations which are All Saints, Langdon Park, Poplar and West India Quay. The nearest London Underground station is Canary Wharf.

The district is well served by a number of London Buses services, 15, 115, D6, N15, N551 run via East India Dock Road, and the 309 run in the areas north of Chrisp Street Market.[35] 108 runs from Violent Road to East India Dock Road and to the Blackwall Tunnel and the D8 runs on the Blackwall Tunnel Northern Approach and Poplar High Street and onto Billingsgate Way.[36]

135, 277, D3, D7, N550 and routes.

The 277 from Highbury formally used to start/end on Saffron Lane in Poplar but was referred to as Leamouth but this was withdrawn in 2016 and replaced by the D3, which itself was withdrawal from Poplar and rerouted to Leamouth in 2017.[37]

References

- 1 2 The History of the Countryside, Oliver Rackham, 1986, p207

- ↑ The Concise Dictionary of English Place Names, 4th Edition, Ekwall

- ↑ Bernard Lambert (1806). The history and survey of London and its environs. 4. London. p. 134. OCLC 647659045.

- ↑ Air Commodore Lionel Charlton, "The Air Defence of Britain", Penguin Books, London, October 1938

- ↑ {{http://www.cwgc.org/find-a-cemetery/cemetery/4004495/POPLAR,%20METROPOLITAN%20BOROUGH}}CWGC List of Civilian War Dead, Poplar Metropolitan Borough.

- ↑ London Children in War-Time Oxford: A Survey of Social and Educational Results of Evacuation. Oxford: Barnett House, 1947, p. 12

- ↑ "Teddy Baldock, 'The Pride of Poplar'".

- ↑ Stevens, Todd. The Pirate John Mucknell. p. 18.

- ↑ "Fly a Flag for Poplar". Time Out. 1974. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ↑ E14: A Dying Trade on IMDb

- ↑ "Welcome to AB Fine Art Foundry". Welcome to AB Fine Art Foundry. Retrieved 2018-07-09.

- ↑ "About | Poplar Union". Poplar Union. 2016-09-14. Retrieved 2018-07-09.

- ↑ "Spotlight on Poplar Union". www.londoncalling.com. Retrieved 2018-07-09.

- ↑ "The Street Art of Chrisp Street in Poplar - Inspiring City". Inspiring City. 2017-06-11. Retrieved 2018-07-09.

- ↑ "Street Artists Boe & Irony Paint a Giant Chihuahua on Chrisp Street in East London - Inspiring City". Inspiring City. 2014-06-22. Retrieved 2018-07-09.

- ↑ "Street Artist Paints 46 Shop Shutters In 48 Hours". Londonist. 2014-08-11. Retrieved 2018-07-09.

- ↑ "The Hidden Banksy in Poplar · Look Up London · Revealing secrets above your eyeline..." Look Up London · Revealing secrets above your eyeline... 2017-03-03. Retrieved 2018-07-09.

- ↑ "Step Inside London's Spratt's Factory". Warehouse Home. Retrieved 2018-07-09.

- ↑ "Michael Green | Axisweb". Axisweb. Retrieved 2018-07-09.

- ↑ "EXCLUSIVE: Artist squares up to Regulator over "manifestly unreasonable" fundraising investigation". ArtsProfessional. Retrieved 2018-07-09.

- ↑ "The Balfron Tower: a tale of gentrificiation | Eastlondonlines". Eastlondonlines. 2014-05-20. Retrieved 2018-07-09.

- ↑ "Balfron Tower". www.balfrontower.com. Retrieved 2018-07-09.

- ↑ "Low Cost Residential Accommodation for artists | Bow Arts". bowarts.org. Retrieved 2018-07-09.

- ↑ "Two dreams coming true" (PDF). Josephites-CJ. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2013. CJ 2012-31

- ↑ "Poplar High Street: Introduction". www.british-history.ac.uk. British History online. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ↑ http://www.eastlondonadvertiser.co.uk/news/politics/fury-at-tower-hamlets-over-knock-down-sale-of-old-poplar-town-hall-1-3229395

- ↑ http://bowlsclub.org/club/1707/

- ↑ https://sports-facilities.co.uk/sites/view/1200553

- ↑ Fuller, Tony (1998). Memorial Inscriptions at the East India Chapel, Poplar. Hornchurch: Armenians in India Press.

- ↑ Historic England. "Details from image database (206382)". Images of England. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- ↑ "Guildmore". June 2013. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ↑ "Poplar Baths reopens after closing its doors nearly 30 years ago". Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ↑ "Heritage at risk 2016". English Heritage.

- ↑ http://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/docklands%7COfficial website

- ↑ http://content.tfl.gov.uk/bus-route-maps/poplar-a4-300917.pdf

- ↑ http://content.tfl.gov.uk/emails/bus/routes-108-d8-diversion.pdf

- ↑ Bus Services Changes 19 August to 8 October inclusive Transport for London

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Poplar. |

- Poplar photographs in the Local History Library