Bethnal Green

| Bethnal Green | |

|---|---|

Stairway to Heaven, also seen is Bethnal Green tube station and St John Church | |

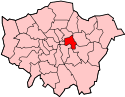

Bethnal Green Bethnal Green shown within Greater London | |

| Population | 27,849 (Bethnal Green North and Bethnal Green South wards 2011)[1] |

| OS grid reference | TQ345825 |

| • Charing Cross | 3.3 mi (5.3 km) SW |

| London borough | |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LONDON |

| Postcode district | E1 E2 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| EU Parliament | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

Bethnal Green is a district in the East End of London, England,[2][3][4] 3.3 miles (5.3 km) northeast of Charing Cross.

Historically a hamlet in the ancient parish of Stepney, Middlesex, following population increases caused by the expansion of London in the 18th century, it was split off from Stepney as the parish of Bethnal Green in 1743, becoming part of the Metropolis in 1855 and the County of London in 1889. The parish became the Metropolitan Borough of Bethnal Green in 1900.

The economic history of Bethnal Green is characterised by a shift away from agricultural provision for the City of London to market gardening, weaving and light industry, which has now all but disappeared. The quality of the built environment had deteriorated by the turn of the 20th century and was radically altered by aerial bombardment in the Second World War and the subsequent social housing developments. In 1943, 173 people were killed at a single incident at Bethnal Green Underground station and in 2005 the area along with neighbouring Haggerston suffered a terrorist attack on a London Buses route 26 bus in the 21 July 2005 London bombings on Hackney Road. Bethnal Green has formed part of Greater London since 1965.

History

Toponymy

The place name Blithehale or Blythenhale, the earliest form of Bethnal Green, is derived from the Anglo-Saxon healh ("angle, nook, or corner") and blithe ("happy, blithe"), or from a personal name Blitha. Nearby Cambridge Heath (Camprichesheth), is unconnected with Cambridge and may also derive from an Anglo-Saxon personal name. The area was once marshland and forest which, as Bishopswood, lingered in the east until the 16th century.[5] Over time, the name became Bethan Hall Green, which, because of local pronunciation as Beth'n 'all Green, had by the 19th century changed to Bethnal Green.

Early history

A Tudor ballad, the Blind Beggar of Bethnal Green, tells the story of an ostensibly poor man who gave a surprisingly generous dowry for his daughter's wedding. The tale furnishes the parish of Bethnal Green's coat of arms. According to one version of the legend, found in Thomas Percy's Reliques of Ancient English Poetry published in 1765, the beggar was said to be Henry, the son of Simon de Montfort, but Percy himself declared that this version was not genuine.[6] The Blind Beggar public house in Whitechapel is reputed to be the site of his begging.

Boxing has a long association with Bethnal Green. Daniel Mendoza, who was champion of England from 1792 to 1795 though born in Aldgate, lived in Paradise Row on the western side of Bethnal Green for 30 years. Since then numerous boxers have been associated with the area, and the local leisure centre, York Hall, remains notable for presentation of boxing bouts.

In 1841, the Anglo-Catholic Nathaniel Woodard, who was to become a highly influential educationalist in the later part of the 19th century, became the curate of the newly created St. Bartholomew's in Bethnal Green. He was a capable pastoral visitor and established a parochial school. In 1843, he got into trouble for preaching a sermon in which he argued that The Book of Common Prayer should have additional material to provide for confession and absolution and in which he criticised the "inefficient and Godless clergy" of the Church of England. After examining the text of the sermon, the Bishop of London condemned it as containing "erroneous and dangerous notions". As a result, the bishop sent Woodard to be a curate in Clapton.

The Green and Poor's Land

The Green and Poor's Land is the area of open land now occupied by Bethnal Green Library, the V&A Museum of Childhood and St John's Church, designed by John Soane. In Stow's Survey of London (1598) the hamlet was called Blethenal Green. It was one of the hamlets included in the Manor of Stepney and Hackney. Hackney later became separated.

In 1678 the owners of houses surrounding the Green purchased the land to save it from being built on and in 1690 the land was conveyed to a trust under which it was to be kept open and rent from it used for the benefit of poor people living in the vicinity. From that date, the trust has administered the land and its minute books are kept in the London Metropolitan Archives.

Bethnal House, or Kirby's Castle, was the principal house on the Green. One of its owners was Sir Hugh Platt (1552–1608), author of books on gardening and practical science. Under its next owner it was visited by Samuel Pepys.

In 1727 it was leased to Matthew Wright and for almost two centuries it was an asylum. Its two most distinguished inmates were Alexander Cruden, compiler of the Concordance to the Bible, and the poet Christopher Smart. Cruden recorded his experience in The London Citizen Grievously Injured (1739) and Smart's stay there is recorded by his daughter. Records of the asylum are kept in the annual reports of the Commissioner in Lunacy. Even today, the park where the library stands is known locally as "Barmy Park".

The original mansion, the White House, was supplemented by other buildings. In 1891 the Trust lost the use of Poor's Land to the London County Council. The asylum reorganised its buildings, demolishing the historic White House and erecting a new block in 1896. This building became the present Bethnal Green Library. A history of Poor's Land and Bethnal House is included in The Green, written by A.J. Robinson and D.H.B. Chesshyre.

Other houses on the Green

The north end of the Green is associated with the Natt family. During the 18th century they owned many of its houses. Netteswell House is the residence of the curator of the Bethnal Green Museum. It is almost certainly named after the village of Netteswell, near Harlow, whose rector was the Rev. Anthony Natt. A few of its houses have become University settlements. In Victoria Park Square, on the east side of the Green, No. 18 has a Tudor well in its cellar.[7]

Globe Town

On the eastern side of Bethnal Green lies Globe Town, established from 1800 to provide for the expanding population of weavers around Bethnal Green attracted by improving prospects in silk weaving. The population of Bethnal Green trebled between 1801 and 1831, operating 20,000 looms in their own homes. By 1824, with restrictions on importation of French silks relaxed, up to half these looms became idle and prices were driven down. With many importing warehouses already established in the district, the abundance of cheap labour was turned to boot, furniture and clothing manufacture. Globe Town continued its expansion into the 1860s, long after the decline of the silk industry.[8]

Globe Town has three globe sculptures situated in three corners of the area. The main shopping area is known as Globe Town Market, and is located on the northern border with Bethnal Green next to the Cranbrook Estate. The area is home to a large Bangladeshi community.

Modern history

The silk-weaving trade spread eastwards from Spitalfields throughout the 18th century. This attracted many Huguenot and Irish weavers to the district. Large estates of small two story cottages were developed in the west of the area to house them. A downturn in the trade in 1769 led to the Spitalfield Riots, and on 6 December 1769, two weavers accused of "cutting" were hanged in front of the Salmon and Ball public house.

In the 19th century, Bethnal Green remained characterised by its market gardens and by weaving. Having been an area of large houses and gardens as late as the 18th century, by about 1860 Bethnal Green was mainly full of tumbledown old buildings with many families living in each house. By the end of the century, Bethnal Green was one of the poorest slums in London. Jack the Ripper operated at the western end of Bethnal Green and in neighbouring Whitechapel. In 1900, the Old Nichol Street rookery was demolished, and the Boundary Estate opened on the site near the boundary with Shoreditch. This was the world's first council housing, and brothers Lew Grade and Bernard Delfont were brought up here.[9] In 1909, the Bethnal Green Estate was built with money left by the philanthropist William Richard Sutton which he left for "modern dwellings and houses for occupation by the poor of London and other towns and populous places in England".[10][11]

World War Two began in 1939 between the Allies and Axis, and the Germen Luftwaffe began an air campaign called The Blitz on 7 September 1940 over the United Kingdom including Bethnal Green that was termed "Target Area A" along with the rest of the East End of London by the Nazis.[12]

Bethnal Green Library was bombed on the very first night of the Blitz. This forced the temporary relocation of the library into the unopened Bethnal Green Underground Station in order to provide a continuous of lending services. The library was rebuilt and opened a few months later for the public.[13] Oxford House also had major role, with some local residents would fleeing into the house off Bethnal Green Road seeking shelter, this location was more attractive than the stables under the nearby Great Eastern Main Line arches. The Chief Shelter Welfare Officer at the time, Jane Leverson said "people came to Oxford House not because it was an air raid shelter but because there they found happiness and a true spirit of fellowship".[14]

On 3 March 1943 at 8:27PM the unopened Bethnal Green Underground station was the site of a wartime disaster. Families had crowded into the underground station due to an air raid siren at 8:17, one of ten that day. There was a panic at 8:27 coinciding with the sound of an anti-aircraft battery (possibly the recently installed Z battery) being fired at nearby Victoria Park. In the wet, dark conditions the crowd was surging forward towards the shelter when a woman tripped on the stairs, causing many others to fall. Within a few seconds 300 people were crushed into the tiny stairwell, resulting in 173 deaths. Although a report was filed by Eric Linden with the Daily Mail, who witnessed it, it never ran. The story which was reported instead was that there had been a direct hit by a German bomb. The results of the official investigation were not released until 1946.[15] A plaque at the entrance to the tube station commemorates it as the worst civilian disaster of the Second World War; and a larger memorial stands in nearby Bethnal Park. The memorial was unveiled in December 2017 at a ceremony attended by Mayor of London Sadiq Khan and Bethnal Green and Bow MP Rushanara Ali.[16]

It is estimated that during the Second World War, 80 tons of bombs fell on the Metropolitan Borough of Bethnal Green, affecting 21,700 houses, destroying 2,233 and making a further 893 uninhabitable. There were a total of 555 people killed and 400 seriously injured.[17] Many unexploded bombs remain in the area, and on 14 May 2007, builders discovered a Second World War 1 m long 500 lb (230 kg) bomb.[18]

The book Family and Kinship in East London (1957) shows an improvement in working class life. Husbands in the sample population no longer went out to drink but spent time with the family. As a result, both birth rate and infant death rate fell drastically and local prosperity increased. It is true that the infamous gangsters, the Kray twins lived in Bethnal Green in the 1960s. However, by the beginning of the 21st century, Bethnal Green and much of the old East End began to undergo a process of gentrification.

The former Bethnal Green Infirmary, later the London County Council Bethnal Green Hospital, stood opposite Cambridge Heath railway station. The hospital closed as a public hospital in the 1970s and was a geriatric hospital under the NHS until the 1980s. Much of the site was developed for housing in the 1990s but the hospital entrance and administration block remains as a listed building. The Albion Rooms are located in Bethnal Green where Pete Doherty and Carl Barât of the Libertines used to live when the band was together. It became part of music history as the band would hold Guerilla Gigs in the flat that would be packed with people.

The London Chest Hospital, founded in 1848 by Thomas Bevill Peacock, was located in Approach Road and first opened in 1855. It closed on 17 April 2015 and its functions transferred to other sites of the Barts Health NHS Trust.[19][20]

Geography

Bethnal Green is centred around the Central line tube station at the junction of Bethnal Green Road, Roman Road and Cambridge Heath Road.

The district is associated with the E2 postcode district, but this also covers parts of Shoreditch, Haggerston and Cambridge Heath. Between 1986 and 1992, the name Bethnal Green was applied to one of seven neighbourhoods to which power was devolved from the council. This resulted in replacement of much of the street signage in the area that remains in place.[21] This included parts of both Cambridge Heath and Whitechapel (north of the Whitechapel Road) being more associated with the post code and administrative simplicity than the historic districts.

Societal

- Demographics

Bethnal Green had a total population of 27,849 at the 2011 census, based on the north and south wards of Bethnal Green.[22] The largest single ethnic group is people of Bangladeshi descent, which constitute 38 percent of the area's population. Every year since 1999 the Baishakhi Mela is celebrated in Weaver's Field, Bethnal Green which celebrates the Bengali New Year.".[23] The second largest are the White British, constituting 30 percent of the area's population. Other ethnic groups include Black Africans and Black Caribbeans.[24]

- Community

Bethnal Green is the vibrant heart of the East End of London[25], has long been a destination for people from across Tower Hamlets and beyond.[26]

United by Suffragette activity,[27] and World War 2[28], Bethnal Green along with the communities of Poplar, Mile End and Bow are known for its shared vibrancy and cultural activity, its places and people. Together they form a wider association of communities that make up the heart of London’s East End with a rich and deep history and proud political heritage[29][30]

- Religion

The two main faiths of the people are Islam and Christianity, with 50 percent Muslim and 34 percent Christians.[31]

There are many historical churches in Bethnal Green. Notable churches include St John on Bethnal Green,[32] located near Bethnal Green Underground station, on Bethnal Green Road and Roman Road. The church was built from 1826 to 1828 by the architect John Soane. Other notable churches include St Matthew - built by George Dance the Elder in 1746. St Matthew is the mother church of Bethnal Green; the church's opening coincided with a vast population increase in the former village of Stepney, resulting in the need to separate the area around Bethnal Green from the mother Parish of St Dunstan's, Stepney. All but the bell tower, still standing today, was destroyed by fire and the church again suffered devastating damage during the bombing campaigns of the Second World War, resulting in the installation of a temporary church within the bombed-out building. St. Matthew's remains a major beacon of the local East End community and is frequented on Sundays and other religious occasions by a mixture of established locals and more recent migrants to the area.[33]

Other churches include St Peter's (1841) and St James-the-Less (1842), both by Lewis Vulliamy, St James the Great by Edward Blore (1843) and St Bartholomew by William Railton (1844). The church attendance in Bethnal Green was 1 in 8 people since 1900, and is estimated around 100 people attend church today (only 10% attend regularly in the UK). Baptisms, marriages and burials have been deposited nearly at all churches in Bethnal Green.[34][35]

There are two Roman Catholic churches, St Casimir's and the Church of Our Lady of the Assumption,[36] in Bethnal Green. St Casimir serves London's Lithuanian community and masses are held in both Lithuanian and English.[37] The Church of Our Lady of the Assumption hosts the London Chinese Catholic Centre and Chinese mass is held weekly.[38]

Other Christian churches include The Good Shepherd Mission,[39] The Bethnal Green Medical Mission,[40] The Bethnal Green Methodist Church.[41]

The Quakers hold regular meetings in Old Ford Road.[42]

There are at least eight Islamic mosques or places of worship in Bethnal Green for the Muslim community.[43] These include the Baitul Aman Mosque and Cultural Centre,[44] Darul Hadis Latifiah,[45] the Senegambian Islamic Cultural Centre and the Globe Town Mosque and Cultural Centre.

The London Buddhist Centre, at 51 Roman Road, is one of the largest urban Buddhist centres in the West, and is the focus of a large Buddhist residential and business community in the area.

- Animals

In recent times, Bethnal Green has become known for it being a friendly animal and human community. Lady Dinah’s Cat Emporium was the first cat café in London, which was opened in 2013.[46][47] The area has also hosted the first catfest in Cambridge Heath Ovel Space in 2018, with guests having the chance to take photos with felines as well as street food and meeting shelter kittens.[48][49]

While also in 2018, the Camel Pub was voted the best pet friendly pub in the world, due for allowing dogs and cats to come in and have a bowl of water, as well as for the two pub cats.[50]

- Amenities and landmarks

Bethnal Green Gardens is located in the heart of Bethnal Green, which holds a war memorial, known as the Stairway To Heaven,[51] and Weavers Fields, a 15.6 acres park and is the 6th largest open space in Tower Hamlets that lies south of Bethnal Green Road.[52] and also has the historical Grade II listed Boundary Gardens at Arnold Circus in the very heart of the Boundary Estate close to Shoreditch.[53]

The historic York Hall is a leisure centre but is far better known as one of Britain's best and most important boxing venue, situated on Old Ford Road. It opened in 1929 with a capacity of 1,200,[54]

Across the road, a branch of the Victoria and Albert Museum (the "V&A") called the V&A Museum of Childhood that was founded in 1872 as the Bethnal Green Museum, has the largest collection of childhood objects in the United Kingdom,[55] and is a Grade II listed building.[56]

Education

Bethnal Green has numerous primary schools serving children aged three to 11. St. Matthias School on Bacon Street,[57] off Brick Lane, is over a century old and uses the Seal of the old Metropolitan Borough of Bethnal Green as its badge and emblem. The school is over a century old but underwent extensive remodelling in 1994 and added a new sports hall on its Granby Street former playground site in 2006. The school is linked with the nearby 18th-century St. Matthew's Church on St. Matthew's Row. The Bangabandhu Primary School, named after the father of Bangladesh, Sheikh Mujib, a non-selective state community school,[58] was opened in January 1989, moved to a new building in November 1991, and has over 450 pupils. 70% of the school's pupils speak English as a second language, with a majority speaking Sylheti, a dialect of Bengali, at home. One of several independent schools in the area, Gatehouse School, near Victoria Park, was established in 1948, and follows a Montessori-style curriculum for younger pupils.

Bethnal Green's oldest secondary school is Raine's Foundation School, with sites on Old Bethnal Green and Approach roads, a voluntary aided Anglican school founded in 1719.[59] The school relocated several times, amalgamating with St. Jude's School [60] to become coeducational in 1977. Bethnal Green Academy, is one of the top schools and sixth form colleges in London, Other schools in the area include Oaklands School, and Morpeth School.

The V&A Museum of Childhood on Cambridge Heath Road houses the child related objects of the Victoria and Albert Museum.[61]

The Bethnal Park and Bethnal Green Library provide leisure facilities and information.

Transport

- Public Transport

- London Overground: Bethnal Green (not to be confused with the London Underground station of the same name) on the Enfield & Cheshunt & Chingford Lines that opened in 1872 as Bethnal Green Junction until 1946:[62] it was also formerly served by trains on the Great Eastern Main Line (GEML) via Stratford. Whilst the majority of Shoreditch High Street railway station which opened in 27 April 2010 is situated within Shoreditch in Hackney, the station entrance on Braithwaite Street is actually within Bethnal Green and the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. The station is served by London Overground's extended East London Line

- London Underground: Bethnal Green opened on 4 December 1946 on the Central Line however construction of the Central line's eastern extension was started in the 1930s, and the tunnels were largely complete at the outbreak of the Second World War although rails were not laid and was a site of a major wartime disaster during the war. The station is part of the Night Tube service since 2016.[63]

- London Buses: Routes 8, 26, 48, 55, 106, 254, 309, 388, D3, D6, N8, N26, N55, N253.

- Santander Cycles: 14 docking stations presently in Bethnal Green.[64]

Sport and leisure

Non-League football club Bethnal Green United F.C. plays at Mile End Stadium. Now known as Tower Hamlets FC (since 2014-15 season), it plays in the Essex Senior League. Another locally based team also based at Mile End Stadium are Sporting Bengal FC. The boxer Joe Anderson, 'All England' champion of 1897, was from Bethnal Green.[65] Bethnal Green is also home to London's only full-time self-defence school Apolaki Krav Maga & Dirty Boxing[66]

Location

See also

References

- ↑ Census Information Scheme (2012). "2011 Census Ward Population Estimates". Greater London Authority. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ https://www.towerhamlets.gov.uk/Documents/Planning-and-building-control/Development-control/Conservation-areas/Bethnal-Green-GardensV1.pdf

- ↑ https://www.towerhamlets.gov.uk/Documents/Planning-and-building-control/Development-control/Conservation-areas/Old-Bethnal-Green-RoadV1.pdf

- ↑ https://www.towerhamlets.gov.uk/Documents/Planning-and-building-control/Development-control/Conservation-areas/Globe-RoadV1.pdf

- ↑ Bethnal Green: Settlement and Building to 1836, A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 11: Stepney, Bethnal Green (1998), pp. 91-95 accessed: 6 December 2007.

- ↑ Blind Beggar of Bethnal Green (East London History) Archived 30 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. accessed 3 December 2007 http://web.archive.bibalex.org/web/20041013043157/http://www.eastlondonhistory.com/blind+beggar.htm. Archived from the original on 13 October 2004. Retrieved 28 January 2017. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ The Green, Land assessments records, Gascoyne's survey of 1703.

- ↑ From 1801 to 1821, the population of Bethnal Green more than doubled and by 1831 it had trebled. These incomers were principally weavers. For further details see: Andrew August Poor Women's Lives: Gender, Work and Poverty in Late-Victorian London pp 35-6 (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1999) ISBN 0-8386-3807-4

- ↑ 'Bethnal Green: Building and Social Conditions from 1876 to 1914', A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 11: Stepney, Bethnal Green (1998), pp. 126-32 accessed: 14 November 2006

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 19 August 2012. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 23 January 2012. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ↑ Oakley, Malcolm (7 October 2013). "East London in the Second World War". Eastlondonhistory.co.uk. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ↑ Julia Gregory. "East End library remembers the Blitz | Latest Norfolk and Suffolk News - Eastern Daily Press". Edp24.co.uk. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ↑ "The Blitz". Oxford House. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ↑ Bethnal Green - disaster at the tube, Wednesday 24 September 2003, 19.30 BBC Two Archived 13 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "WW2 Tube tragedy memorial unveiled". BBC News. 17 December 2017. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ↑ Bethnal Green: Building and Social Conditions from 1915 to 1945, A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 11: Stepney, Bethnal Green (1998), pp. 132-135 accessed: 10 October 2007

- ↑ "Families kept away by World War II bomb". BBC News. 16 May 2007. Retrieved 16 May 2007.

- ↑ "The History of the London Chest Hospital". Barts and the London NHS Trust. Archived from the original on 2 April 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ↑ "The London Chest". Barts Health. n.d. Archived from the original on 23 April 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ↑ Tower Hamlets Borough Council Election Maps 1964-2002 accessed 14 April 2007

- ↑ Services, Good Stuff IT. "Tower Hamlets - UK Census Data 2011". UK Census Data. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ↑ May 2009 Archived 23 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Londontown.com. Retrieved on 2009-04-29.

- ↑ http://www.ukcensusdata.com/bethnal-green-south-e05000574

- ↑ https://www.tripadvisor.co.uk/ShowUserReviews-g186338-d2437653-r348097062-Bethnal_Green-London_England.html

- ↑ https://www.towerhamlets.gov.uk/lgnl/community_and_living/town_centres/bethnal_green_road/bethnal_green_road.aspx

- ↑ http://spitalfieldslife.com/2018/02/07/celebrating-east-end-suffragettes/

- ↑ https://www.eastlondonhistory.co.uk/world-war-2-east-london/

- ↑ https://www.rushanaraali.org/about_bethnal_green_and_bow

- ↑ http://the-east-end.co.uk/culture/

- ↑ Neighbourhood Statistics. "ONS". Neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ↑ "St John on Bethnal Green". Archived from the original on 26 July 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ↑ "St-Matthews". St-Matthews. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ↑ Susan Gane. "Bethnal Green Churches". Dickens-and-london.com. Archived from the original on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ↑ EoLFHS Parishes: Bethnal Green Archived 19 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Our Lady of the Assumption". Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ↑ "St Casimir's Lithuanian Church". Official website. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ↑ "London Chinese Catholic Centre". Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ↑ "Good Shepherd Mission". Good Shepherd Mission. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ↑ "Bethnal Green Medical Mission". Bethnal Green Mission Church. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ↑ "Methodist Church in Tower Hamlets, Bethnal Green Meeting". The Methodist Church in Tower Hamlets, Bethnal Green Meeting. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ↑ "Bethnal Green Friends". Bethnal Green Quaker Meeting. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ↑ "mosquedirectory.co.uk". Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ↑ Services of Baitul Aman Mosque Archived 16 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Darul Hadis Latifah". Darulhadis.org.uk. Archived from the original on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ↑ https://www.getwestlondon.co.uk/whats-on/food-drink-news/secret-alice-wonderland-cat-caf-13365776

- ↑ https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/londons-first-cat-caf-gets-green-light-8811383.html

- ↑ https://www.standard.co.uk/go/london/attractions/paw-blimey-a-cat-festival-is-coming-to-london-next-year-a3662101.html

- ↑ https://www.timeout.com/london/blog/stop-the-mewsic-a-cat-festival-is-coming-to-london-101717

- ↑ https://metro.co.uk/2018/08/11/camel-bethnal-green-best-pet-friendly-pub-world-7826822/

- ↑ "Bethnal Green Gardens". Towerhamlets.gov.uk. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ↑ "Weavers Fields |". Lovebethnalgreen.com. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ↑ Please enter your name here (6 February 2018). "Boundary Gardens, Arnold Circus | Case studies". Landscape Institute. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ↑ Boxing: Harrison calls for York Hall reprieve Sandra Laville (The Daily Telegraph) accessed 7 December 2007

- ↑ http://www.vam.ac.uk/moc/

- ↑ Historic England. "Details from image database (205816)". Images of England. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- ↑ "Ofsted inspection report for Saint Matthias School". Ofsted. Retrieved 5 February 2009.

- ↑ A-Z Services - Tower Hamlets Archived 26 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Bell, Walter George (1966). "raine's+foundation+school"+history&dq="raine's+foundation+school"+history Unknown London. Spring Books. p. 326.

- ↑ Johnson, Malcolm (2001). Bustling Intermeddler? The Life and Works of Charles James Blomfield. Gracewing. p. 109. ISBN 0-85244-546-6.

- ↑ "About us". V&A Museum of Childhood. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ↑ Forgotten Stations of Greater London by J.E.Connor and B.Halford

- ↑ "Bethnal Green Underground Station - Transport for London". Tfl.gov.uk. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ↑ "Nearby Bethnal Green Station - Transport for London". Tfl.gov.uk. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ↑ "Bare-Knuckle Fighter". Antiques Roadshow Detectives. Series 1. Episode 3. 8 April 2015. BBC Television. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ↑ http://www.apolakikravmagalondon.com Archived 5 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

External links

- "Tower Hamlets London Borough Council information about Bethnal Green". Archived from the original on 9 November 2005.