Enfield Town

| Enfield Town | |

|---|---|

Enfield Town centre | |

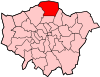

Enfield Town Enfield Town shown within Greater London | |

| Population | 14,906 (2011 Census. Town Ward)[1] |

| OS grid reference | TQ325965 |

| London borough | |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | ENFIELD |

| Postcode district | EN1, EN2 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| EU Parliament | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

Enfield Town, also known as Enfield, is the historic centre of the London Borough of Enfield. It is 10.1 miles (16.3 km) north-northeast of central London. The area is identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London.[2] The town was originally in the county of Middlesex, but became part of Greater London on 1 April 1965 when the London Government Act 1963 was commenced. Enfield Town had a population of 115,762 in 2011.

History

Enfield was a set settlements united by one church, including by the High Middle Ages in 1303 a small agrarian market town, otherwise hamlets spread around the royal hunting grounds of Enfield Chase. At the time of the Domesday Book the area was spelt 'Enefelde', and had a priest who almost certainly resided in St. Andrew's Church. By 1572 most of the long-distance streets had been completed. The village green, in 1303, became a marketplace making the place a market town; the area between the church and the present fountain. Traders sell products at the regular market, on licence by a non-discriminatory poor relief charity covering the whole Borough. Its name most likely came from Anglo-Saxon Ēanafeld or similar, meaning "open land belonging to a man called Ēana" or "open land for lambs". The parish was the largest in Middlesex if excluding from Harrow its Pinner north-west corner, which broke away in 1766; Enfield measured 12,460 acres in 1831, i.e. 19.5 square miles (51 km2).[3]

Notable people, places, and events

The parish church, on the north side of the marketplace, is dedicated to St Andrew. There is some masonry surviving from the thirteenth century, but the nave, north aisle, choir and tower are late fourteenth century, built of random rubble and flint. The clerestory dates from the early sixteenth century, and the south aisle was rebuilt in brick in 1824.[4] Adjacent to the church is the old school building of the Tudor period, Enfield Grammar School, which expanded over the years, becoming a large comprehensive school from the late 1960s.

Enfield Palace

A sixteenth century manor house, known since the eighteenth century as Enfield Palace, is remembered in the name of the Palace Gardens Shopping Centre (and the hothouses on the site were once truly notable; see below). It was used as a private school from around 1670 until the late nineteenth century. The last remains of it were demolished in 1928, to make way for an extension to Pearson's department store, though a panelled room with an elaborate plaster ceiling and a stone fireplace survives, relocated to a house in Gentleman's Row, a street of sixteenth- to eighteenth-century houses near the town centre.[5]

Enfield Market

In 1303, Edward I granted a charter to Humphrey de Bohun, and his wife to hold a weekly market in Enfield each Monday, and James I granted another in 1617, to a charitable trust, for a Saturday market.[6] The Market was still prosperous in the early eighteenth century, but fell into decline soon afterwards. There were sporadic attempts to revive it: an unsuccessful one of 1778 is recorded,[7] and in 1826 a stone Gothic market cross was erected, to replace the octagonal wooden market house, demolished sixteen years earlier. In 1858, J. Tuff wrote of the market "several attempts have been made to revive it, the last of which, about twenty years ago, also proved a failure, It has again fallen into desuetude and will probably never be revived".[8]

However the trading resumed in the 1870s. In 1904 a new wooden structure was built to replace the stone cross, by now decayed. The market is still in existence, administered by the Old Enfield Charitable trust.[9]

The Enfield Fair

The charter of 1303 also gave the right to hold two annual fairs, one on St Andrew's Day and the other in September.[10] The latter was suppressed in 1869 at the request of local tradesmen, clergy and other prominent citizens, having become, according to the local historian Pete Eyre, "a source of immorality and disorder, and a growing nuisance to the inhabitants".[11]

The New River

The New River, built to supply water to London from Hertfordshire, runs immediately behind the town centre through the Town Park, which is the last remaining public open space of Enfield Old Park. The Enfield Loop of the New River also passes through the playing fields of Enfield Grammar School, and this is the only stretch of the loop without a public footpath on at least one side of it.

Hothouses

Enfield was the location of some of the earliest successful hothouses, developed by Dr Robert Uvedale, headmaster of both Enfield Grammar School and the Palace School. He was a Cambridge scholar and renowned horticulturalist; George Simonds Boulger writes of Uvedale in the Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 58:

As a horticulturist Uvedale earned a reputation for his skill in cultivating exotics, being one of the earliest possessors of hothouses in England. In an Account of several Gardens near London written by J. Gibson in 1691 (Archæologia, 1794, xii. 188), the writer says: 'Dr. Uvedale of Enfield is a great lover of plants, and, having an extraordinary art in managing them, is become master of the greatest and choicest collection of exotic greens that is perhaps anywhere in this land. His greens take up six or seven houses or roomsteads. His orange-trees and largest myrtles fill up his biggest house, and … those more nice and curious plants that need closer keeping are in warmer rooms, and some of them stoved when he thinks fit. His flowers are choice, his stock numerous, and his culture of them very methodical and curious.'

John Keats==== / ====Dusty Springfield

The poet John Keats went to progressive Clarke's School in Enfield, where he began a translation of the Aeneid. The school's building later became Enfield Town railway station until it was demolished in 1872. The current building was erected in the 1960s. In 1840 the first section of the Northern and Eastern Railway had been opened from Stratford to Broxbourne. The branch line from Water Lane to Enfield Town station was opened in 1849. Enfield Town is also the birthplace of one of the world's greatest pop singers of all time, Dusty Springfield. Born Mary Isobel Catherine Bernadette O'Brien OBE[1] (16 April 1939 – 2 March 1999).

Robert Everist

Millionaire businessman, Robert Everist was born in Enfield. He now lives between Nottinghamshire and London where his companies' head offices are based.

Silver Street White House

The White House in Silver Street – now a doctors' surgery – was the home of Joseph Whitaker, publisher and founder of Whitaker's Almanack, who lived there from 1820 until his death in 1895. (Inscription on Blue Plaque on The White House, Silver Street, Enfield.)

World's first ATM

Enfield Town had the world's first cash machine or automatic teller machine, invented by John Shepherd-Barron. It was installed at the local branch of Barclays Bank on 27 June 1967 and was opened by the actor and Enfield resident Reg Varney.[12]

The Civic Centre

Enfield Town houses the Civic Centre, the headquarters of the Borough administration, at which Council and committee meetings are also held.

August 2011 riots

On Sunday 7 August 2011, after rioting spread from Tottenham, vehicles including a police car were attacked and several shops and business were targeted in the town centre. Most businesses remained closed on Monday 8th and many were not repaired for several weeks after the rioting. The mayor of London, Boris Johnson, later visited the town centre to receive people's views of the riots.[13]

Demography

In the 2011 census, the Town ward (covering areas north from the Southbury Road) was 82% white (68% British, 10% Other, 3% Irish). The largest non-white group, Black African, claimed 3%. The District is also covered by the Chase, Highlands, Grange, Southbury, Lock, Highway, Turkey Street and Bush Hill Park wards.

Economy

Enfield Town centre underwent major redevelopment work, completed in Autumn 2006. A large extension to the existing shopping centre was built, under the name Palace Exchange.[14] Many branches of chain stores already existing in the town centre were relocated to the new extension, and there are some completely new stores. In the summer of 2011 a vacant building (previously a bingo club) on Burleigh way in the town centre was demolished and replaced with new apartments, which were completed in the spring of 2012. There is space for six commercial units and public art. A further two apartments are being built on Silver Street and Southbury Road. There are also plans for a fourth new block of flats to be built, which will go ahead if the council approve them.

Sports

The town is home to two association football teams one being Enfield 1893 F.C. and the other being Enfield Town F.C. formed by the original Enfield Supporters' Trust. The original Enfield F.C. played in the Isthmian League until they were liquidated in 2007.

Transport and locale

Nearest places

Nearest railway stations

Enfield Town station is well connected with National Rail services to Liverpool Street in Central London operated by London Overground.

| Preceding station | Following station | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

towards Liverpool Street | Enfield & Cheshunt Line Enfield Town Branch | Terminus |

Services from Enfield Chase station also provide alternative services to Central London and connects the area to Letchworth Garden City.

Buses

Enfield Town has excellent bus links.London Buses routes 121, 191, 192, 231, 307, 313, 317, 329, 377, 629, W8, W9, W10, night route N29, and non-London route 610 serves Enfield Town.

See also

References

- ↑ "Enfield Ward population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 22 October 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ↑ Mayor of London (February 2008). "London Plan (Consolidated with Alterations since 2004)" (PDF). Greater London Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2010.

- ↑ A P Baggs, Diane K Bolton, Eileen P Scarff and G C Tyack, 'Enfield: Introduction', in A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 5 ed. T F T Baker and R B Pugh (London, 1976), pp. 207-208. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/vol5/pp207-208 [accessed 24 May 2018].

- ↑ Historic England. "Details from image database (200594)". Images of England. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ A P Baggs; Diane K Bolton; Eileen P Scarff; G C Tyack (1976). T F T Baker; R B Pugh, eds. "Enfield: Manors". A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 5: Hendon, Kingsbury, Great Stanmore, Little Stanmore, Edmonton Enfield, Monken Hadley, South Mimms, Tottenham. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ Ford (1873) p.101

- ↑ Pam (1990) pp.226

- ↑ Tuff, J. (1858). Historical, Topographical and Statistical Notices of Enfield. Enfield: J.H. Meyers. "

- ↑ "Historical Information". Old Enfield Charitable Trust. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- ↑ Ford (1873) pp. 102

- ↑ Ford (1873) pp. 104-5

- ↑ "The man who invented the cash machine". BBC News. 25 June 2007. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ↑ News report Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 12 August 2011

- ↑ "Enfield". Palace Exchange. Retrieved 2011-06-30.

Bibliography

- Pam, David (1992). A Victorian Suburb. A History of Enfield. Enfield: Enfield Preservation Society.

- Ford, Edward; George H. Hodson (1873). A History of Enfield in the County of Middlesex. Enfield. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- Edward Walford (1883), "Enfield", Greater London, London: Cassell & Co., OCLC 3009761