LGBT rights in the Philippines

| LGBT rights in the Philippines | |

|---|---|

| |

| Same-sex sexual intercourse legal status | Legal |

| Gender identity/expression | Transgender people not allowed to change legal gender |

| Military service | Gays, lesbians and bisexuals allowed to serve openly since 2009 |

| Discrimination protections | None at the national level but many anti-discrimination ordinances exist at the local government level. |

| Family rights | |

| Recognition of relationships | None |

Restrictions: | The Family Code of the Philippines defines marriage as "a special contract of permanent union between a man and a woman". The Constitution of the Philippines does not prohibit same-sex marriage.[1] |

| Adoption | Allowed for individuals but not allowed for same-sex couples. |

| Part of a series on |

| Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) rights |

|---|

|

|

The Philippines is ranked as one of the most gay-friendly nations in Asia.[2] The country ranked as the 10th most gay-friendly in a 2013 global survey covering 39 countries, in which only 17 had majorities accepting homosexuality. Titled "The Global Divide on Homosexuality," the survey conducted by the Pew Research Center showed that 73% of adult Filipinos agreed with the statement that "homosexuality should be accepted by society," up by nine percentage points from 64% in 2002. The main reasons for the high percentage of LGBT acceptance in the Philippines are (1) the archipelago's historic point of view and respect to gender-shifting and non-based gender roles before the 12th century which have been inputted in indigenous cultures prior to Islamization and Christianization and (2) the current public mediums (television, writings, radios, and social media) that have set a spotlight on the sufferings of countless LGBT Filipinos in their own country due to colonial-era and colonial-inspired religions.[2][3]

In the classical era of the country, prior to Spanish occupation, the people of the states and barangays within the archipelago accepted homosexuality. Homosexuals actually had a role of a babaylan, or a local spiritual leader who was the holder of science, arts, and literature. In the absence of the datu of the community, the babaylans, homosexual or not, were also made as leaders of the community. During the Islamic movements in Mindanao which started in Borneo, the homosexual acceptance of the indigenous natives were subjugated by Islamic beliefs. Nevertheless, states and barangays that retained their non-Islamic cultures continued to accept homosexuality. During the Spanish colonization, the Spaniards forcefully instilled Roman Catholicism to the natives which led to the end of acceptance of homosexuality in most of the archipelagic people. These deep Catholic roots nationwide (and some Islamic roots in Mindanao) from the colonial era have resulted in much discrimination, oppression and hate crimes for the LGBT community in the present time.[4][5][6][7]

The LGBT community remains as one of the country's minority sectors today. Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people often face disadvantages in getting hired for jobs, acquiring rights for civil marriage, and even in starting up personal businesses. Most non-heterosexuals also have a higher rate of suicide and suicide ideation compared to non-homosexuals.[8][9] According to an international research, 10% of the world's population are theoretically part of the LGBT community, out or not, including 12 million Filipinos that may experience discrimination based on who they are. This has led to the rise of the cause for LGBT rights, defined as the right to equality and non-discrimination.[10] As a member of the United Nations, the Philippines is signatory to various international covenants promoting human rights.[11]

History

Precolonial period

Priestesses, or babaylan held positions of authority as religious leaders or healers in some precolonial Philippine societies.[12] Cross-dressing or transvestite males sometimes took on the role of the female babaylan.[13]

The babaylan, also called katalonan, bayoguin, bayok, agi-ngin, asog, bido and binabae depending on the ethnic group of the region,[5] held important positions in the community. They were the spiritual leaders of the Filipino communities, tasked with responsibilities pertaining to rituals, agriculture, science, medicine, literature and other forms of knowledge that the community needed.[4] In the absence of a datu, the babaylan could take charge of the whole community.[5]

The role of the babaylan was mostly associated with females, but male babaylans also existed. Early historical accounts record the existence of male babaylans who wore female clothes and took the demeanor of a woman.[6][7] Anatomy was not the only basis for gender. Being male or female was based primarily on occupation, appearance, actions and sexuality. A male babaylan could partake in romantic and sexual relations with other men without being judged by society.[5]

Precolonial society accepted gender-crossing and transvestism as part of their culture. Rituals and trances performed by the babaylan mirrored the reunification of the opposites, the male and female. They believed that by doing this they would be able to exhibit spiritual potency, which would be used for healing spiritual brokenness. Outside this task, male babaylans sometimes indulged in homosexual relations.[5]

During the Islamisation of Mindanao, barangays and states influenced by Islam expelled the belief of homosexual acceptance. Nevertheless, states and barangays that were not Islamised continued to practice acceptance on homosexuality and gender-bending cultures and belief systems.

Spanish colonial period

The Spanish conquistadors introduced a predominantly patriarchal culture to the precolonial Philippines. Males were expected to demonstrate masculinity in their society, alluding to the Spanish machismo or a strong sense of being a man.[14][15] Confession manuals made by the Spanish friars during this period suspected that the natives were guilty of sodomy and homosexual acts. During the 17th-18th century, Spanish administrators burned sodomites to enforce the decree made by Pedro Hurtado Desquibel, President of Audiencia.[5]

Datus were appointed as the district officers of the Spaniards while the babaylans were reduced to relieving the worries of the natives. The removal of the datu system of localized governance affected babaylanship.[5] The babaylans eventually disappeared with the colonization of the Spaniards. Issues about sexual orientation and gender identity were not widely discussed after the Spanish colonization.[16]

American colonial period

Four decades of American occupation saw the promulgation and regulation of sexuality through a modernized mass media and a standardized academic learning. Furthered by the growing influence of Western biomedicine, it conceived a specific sexological consciousness in which the "homosexual" was perceived and discriminated as a pathological or sick identity. Filipino homosexuals eventually identified to this oppressive identity and began engaging in projects of inversion, as the disparity of homo and hetero entrenched and became increasingly salient in the people's psychosexual logic.[17][18]

Though American colonialism brought the Western notion of "gay" and all its discontents, it also simultaneously refunctioned to serve liberationist ends. While it stigmatized the local homosexual identity, the same colonialism made available a discussion and thus a discursive position which enabled the homosexualized bakla to speak.[18] It was during the neocolonial period in the 1960s that a conceptual history of Philippine gay culture began to take form, wherein a "subcultural lingo of urban gay men that uses elements from Tagalog, English, Spanish and Japanese, as well as celebrities' names and trademark brands" developed, often referred to as swardspeak, gayspeak or baklese.[19] Gay literature that was Philippine-centric also began to emerge during this period.[20] Further developments in gay literature and academic learning saw the first demonstrations by LGBT political activists, particularly LGBT-specific pride marches.[21]

Martial law

During the implementation of the Martial Law, citizens were silenced by the Government through the military. People, including the LGBT community, did not have a voice during this period, and many were harassed and tortured. At the behest of Imelda Marcos, an anti-gay book was published that clarified the agonistic situation of gay culture at the same time that all other progressive movements in the country was being militaristically silenced.[22] There were some homosexuals that were exiled by Marcos in America where they joined movements advocating the rights of the LGBT people.[23] The community responded to this through the use of several mediums, such as the 1980s film Manila by Night, which introduces an LGBT character in its plotline.[24] When the regime ended, those exiled returned to the Philippines, introducing new ideas of gay and lesbian conceptions.

1960s, 1970s–1980s

Swardspeak emerged in the 1960s and the pioneering Transgender activist in the time was Helen Cruz who was a singer and performer. During the 1970s and 1980s, Filipino concepts of gay were greatly influenced by Western notions. According to "Being LGBT in Asia: The Philippines Country Report", LGBT people who are exposed to the Western notion of being "gay" starting to have relationships with other LGBT people, instead of with heterosexual-identifying people.[25] Towards the end of the 1980s, an increase in awareness of LGBT Filipinos occurred. In 1984, a number of gay plays were produced and staged.[26] The plays that were released during the said time tackled the process of "coming out" by gay people.[26]

1990s

Based on a report made by USAID, in partnership with UNDP entitled "Being LGBT in Asia: The Philippines Country Report", the LGBT community during the early 90s, made books that helped Filipinos become aware of the prevalence of LGBT communities like Ladlad, an anthology of Philippine gay writing edited by Danton Remoto and J. Neil Garcia and Margarita Go-Singco Holmes’s A Different Love: Being Gay in the Philippines in 1994 and 1993, respectively.[11] This decade also marks the first demonstration of attendance by an organized sector of the country's LGBT community in the participation of a lesbian group called Lesbian Collective, as they join the International Women’s Day march of 1992.[11] Another demonstration of attendance was made by ProGay Philippines and MCC Philippines, led by Oscar Atadero and Fr Richard Mickley respectively, when they organized a Pride march on 26 June 1994, that marked the first Pride-related parade hosted by a country in Asia and the Pacific.[11] And throughout the decade, various LGBT groups were formed such as Metropolitan Community Churches (MCC) in 1991, the University of the Philippines (UP), Babaylan in 1992 and ProGay Philippines in 1993, and according to the report, the 1990s are the "probable maker of the emergence of the LGBT movement in the Philippines".[11] In 1998, the Akbayan Citizens’ Action Party became the first political party to consult the LGBT community and helped with the creation of the first LGBT lobby group, the Lesbian and Gay Legislative Advocacy Network, otherwise known as LAGABLAB, in 1999.[11] LAGABLAB proposed revisions to LGBT rights in 1999 and filed the Anti-Discrimination Bill (ADB) in 2000.[11]

Contemporary (2000s–present)

The LGBT movement has been very active in the new millennium. In the advent of the 2000s, more LGBT organizations were formed to serve specific needs, including sexual health (particularly HIV), psychosocial support, representation in sports events, religious and spiritual needs, and political representation.[11] For example, the political party Ang Ladlad was founded by Danton Remoto, a renowned LGBT advocate, in 2003.[27] The community has also shown their advocacies through the 21st LGBT Metro Manila Pride March held in Luneta Park last June 27, 2015, with the theme, "Fight For Love: Iba-Iba. Sama-Sama". This movement aims to remind the nation that the fight for LGBT rights is a fight for human rights. Advocates are calling on the Philippines to recognize the voices of people of diverse sexual orientations and gender identities.[28] In present time, there remains no umbrella LGBT organization in the Philippines.[11] Therefore, organizations tend to work independently of each other.[11] Due to these divisions, there remains no prioritization of efforts, with organizations focusing on what they consider as important for them.[11]

In December 2004, Marawi City banned gays from going out in public wearing female attire, makeup, earrings "or other ornaments to express their inclinations for femininity". The law passed by the Marawi City Council also bans skintight blue jeans, tube tops and other skimpy attire. Additionally, women (only) must not "induce impure thoughts or lustful desires." The Mayor said these moves were part of a "cleaning and cleansing" drive. People who violate these rules will have paint dumped on their heads by the muttawa, the religious police.[29]

In late 2014, during the interpolations of the Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL), the Filipino Government included a provision which would have allowed the Regional Bangsamoro Government to adhere to Sharia law. The usage of Sharia law would have allow gay people to be stoned to death or whipped in front of a public plaza. Due to the Mamasapano massacre in January 2015, the BBL was not passed by Congress, effectively hindering the passage of Sharia law in the Bangsamoro region.

In a United Nations Assembly for the establishment of an UN-backed LGBT Watch Personnel, the Philippine permanent delegate to the UN abstained from voting. Islamic nations and some eastern European nations voted against its establishment. Nevertheless, countries from Western Europe and the Americas with the backing of Vietnam, South Korea and Mongolia, voted in favor of its establishment. The LGBT Watch Personnel was established after the majority of nations in the meeting voted in its favor.

In 2016, Geraldine Roman became the first openly transgender woman elected to the Congress of the Philippines.[30] Additionally, several openly LGBT people have been elected to local government positions throughout the Philippines, including as mayors or councillors. In Northern Samar, two of the province's 24 municipalities are run by openly LGBT mayors. The provinces of Albay, Cebu, Leyte, Nueva Vizcaya and Quezon as well as Metro Manila have LGBT elected officials.[31]

A few months after the establishment of the UN expert on LGBT rights, an African-led coalition of nations made a move to dislodge the LGBT expert. In November 2016, UN members voted by a majority to retain the UN expert on LGBT issues, however, the representative of the Philippines chose to abstain again, despite outcry of support for the LGBT expert to be retained from various sectors in the country.[32]

In late 2016, the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) under Secretary Judy Taguiwalo enforced a policy, together with the Depertment of Education, where they allowed students to use uniform that match their gender identities, effectively accepting students who dress themselves like the opposite gender.[33]

In July 2017, the Department of Education implemented the Gender-Responsive Basic Education Policy, which entails a review of public schools' curriculum to look at all forms of gender stereotypes, including LGBTIQ. The policy also mandates the observance of gender and development related events in schools; stating that June be celebrated as Pride Month.[34]

According to the report of the ASEAN SOGIE Caucus released on November 2017 in time for the ASEAN Summit, the Philippines is shifting to "a trend to be more open and accepting of LGBT issues" as seen in the rise of cooperation and acceptance from government officials, especially in municipalities and cities nationwide such as Zamboanga City, Metro Manila, Metro Cebu, Metro Davao, Baguio City, and many more. The report also stated that there have been over 20 local government units that have adopted local ordinances on gender equality, but only two cities — Quezon City and Cebu City — have existing implementing rules and regulations (IRR).[35]

On June 19, 2018, the Philippine Supreme Court heard oral arguments in a historic case seeking to legalize same-sex marriage in the Philippines.[36][37][38]

Legality of same-sex sexual activity

Noncommercial, homosexual relations between two adults in private are not a crime, although sexual conduct or affection that occurs in public may be subject to the "grave scandal" prohibition in Article 200 of the Revised Penal Code, which states:

"ARTICLE 200. Grave Scandal. — The penalties of arresto mayor and public censure shall be imposed upon any person who shall offend against decency or good customs by any highly scandalous conduct not expressly falling within any other article of this Code."[39]

In December 2004, Marawi City banned gays from going out in public wearing female attire, makeup, earrings "or other ornaments to express their inclinations for femininity". The law passed by the Marawi City Council also bans skintight blue jeans, tube tops and other skimpy attire. Additionally, women (only) must not "induce impure thoughts or lustful desires." The Mayor said these moves were part of a "cleaning and cleansing" drive. People who violate these rules will have paint dumped on their heads by the muttawa, the religious police. No person or entity has yet to challenge the ordinance in court.[29]

Recognition of same-sex relationships

The Philippines does not offer any legal recognition to same-sex marriage, civil unions or domestic partnership benefits.

Since 2006, three anti-same sex marriage bills have been introduced to the Senate and Congress. In early 2011, Representative Rene Relampagos of Bohol filed a bill to amend Article 26 of the Philippine Family Code, to prohibit "forbidden marriages." Specifically, this sought to bar the Philippines from recognizing same-sex marriages contracted overseas. The bill did not advance.[40][41][42]

In December 2014, Herminio Coloma Jr, a spokesperson for the Presidential Palace, commented on same-sex marriage, saying; "We must respect the rights of individuals to enter into such partnerships as part of their human rights, but we just need to wait for the proposals in Congress".[43]

Right after Ireland legalized same-sex marriage through a popular vote in May 2015, advocates for the legalization of same-sex marriage in the Philippines saw the possibility of legalizing such marriages with a public petition.[44] The Catholic Bishops' Conference of the Philippines, however, is opposed to the idea despite stating that it supports "equality for all". To the extent of even stating that same-sex marriage and "falling for the same sex is wrong".[45]

The Family Code of the Philippines states in Articles 1, 2 and 147, respectively:

"Marriage is a special contract of permanent union between a man and a woman entered into in accordance with law for the establishment of conjugal and family life. It is the foundation of the family and an inviolable social institution whose nature, consequences, and incidents are governed by law and not subject to stipulation, except that marriage settlements may fix the property relations during the marriage within the limits provided by this Code."[46]

"No marriage shall be valid, unless these essential requisites are present:

(1) Legal Capacity of contracting parties who must be a male and a female; and

(2) Consent freely given in the presence of the solemnizing officer."[46]

On 18 February 2016, during his presidential campaign, Rodrigo Duterte announced that should he win the election he would consider legalizing same-sex marriage if a proposal is presented to him.[47] Duterte won the presidential election. In March 2017, however, Duterte said that he personally opposes same-sex marriage.[48] On 17 December 2017, Duterte changed his position on the issue, expressing his support again.[49][50] He further guaranteed that, during his term, the rights of LGBT people in the Philippines would be protected and nurtured.

In October 2016, Speaker of the House of Representatives Pantaleon Alvarez announced that he would file a bill to legalize civil unions for both opposite-sex and same-sex couples. As of 25 October 2016, more than 150 lawmakers have signified their support for the bill.[51] Alvarez introduced the civil partnership bill on 10 October 2017. The bill is also under the wing of representatives Geraldine Roman of Bataan, Gwendolyn Garcia of Cebu, and Raneo Abu of Batangas.[52][53] In the Senate, conservative senators Tito Sotto, Joel Villanueva, Win Gatchalian, and Manny Pacquio have vowed to block the bill if it ever passes the House of Representatives. On the other hand, the bill is supported by senators Risa Hontiveros and Grace Poe. If the historic bill passes Congress, the Philippines would become the first country in Asia to legalize civil unions, regardless of gender.[54]

2018 Supreme Court case

| Falcis III vs. Civil Registrar-General | |

|---|---|

| |

| Court | Supreme Court of the Philippines |

| Full case name | Jesus Nicardo M. Falcis III vs Civil Registrar-General, LGBTS Christian ·Church, Inc., Reverend Crescencio "Ceejay" Agbayani, Jr., Marlon Felipe, and Maria Arlyn "Sugar" Ibanez, petitioners-in-intervention, Atty. Fernando P. Perito, intervenor. |

| Citation(s) | G.R. 217910 |

| Questions presented | |

| Constitutionality of the portions of Article 1 and 2 of the Family Code of the Philippines, which defines marriage as between a man and a woman, and whether said articles violate the Equal Protection Clause, Due Process Clause and religious freedom of the petitioner | |

| Court membership | |

| Judge(s) sitting | Antonio Carpio, Presbitero Velasco Jr., Teresita Leonardo-De Castro, Diosdado Peralta, Lucas Bersamin, Mariano del Castillo, Estela Perlas Bernabe, Marvic Leonen, Francis Jardeleza, Alfredo Benjamin Caguioa, Samuel Martires, Noel Tijam, Andres Reyes Jr., Alexander Gesmundo |

| Keywords | |

| Same-sex marriage | |

On March 2018, the Supreme Court of the Philippines approved the scheduling of a same-sex marriage petition that seeks to invalidate Articles 1 and 2 of the Family Code.[55]

During the second week of June 2018, the Supreme Court announced that they will hear arguments in a case seeking the invalidation of the Family Code's provisions prohibiting same-sex marriage.[56] The petition was filed by Atty. Jesus Falcis in 2015. The historic oral arguments are the first ever of its kind to be heard by the Supreme Court, and is backed by thousands of LGBT organizations in the Philippines, developing nations, and developed democracies, such as Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Canada, France, Spain, Italy, Germany, Taiwan, Japan, Thailand, and the Netherlands. The case is also supported by the country's top universities, including the Ateneo de Manila University and the University of the Philippines Diliman.[57] The news of the historic oral arguments was also reported by the international media. Duterte also expressed his support for same-sex marriage to be legalized in the Philippines.[58]

On June 19, 2018, the first wave of arguments commenced with the following arguments made: whether or not the petition is properly the subject of the exercise of the Supreme Court's power of judicial review, whether or not the right to marry and the right to choose whom to marry are cognates of the right to life and liberty, whether or not the limitation of civil marriage to opposite-sex couples is a valid exercise of police power, whether or not limiting civil marriages to opposite-sex couples violates the Equal Protection Clause, whether or not denying same-sex couples the right to marry amounts to a denial of their right to life and/or liberty without due process of law, whether or not sex-based conceptions of marriage violate religious freedom, whether or not a determination that Articles 1 and 2 of the Family Code are unconstitutional must necessarily carry with it the conclusion that Articles 46(4) and 55(6) of the Family Code (i.e.: homosexuality and lesbianism as grounds for annulment and legal separation) are also unconstitutional, and whether or not the parties are entitled to the reliefs prayed for. The Office of the Solicitor General (OSG) under Jose Calida argued against the case.[37] The second session of arguments took place on June 26, 2018.[2][38]

Two days after the first arguments occurred, the presidential palace of Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte stated that it was "too soon for same-sex marriage in the Philippines", causing outrage from various human rights organizations.[59] Additionally, Senate President Tito Sotto, an ally of the Philippines President, commented: "Same sex union, no problem. Marriage? Debatable", saying that he will vote in favor of same-sex civil unions, a turnaround from previous pronouncements in 2016 and 2017 where he was against both same-sex civil unions and same-sex marriage.[60]

Several Supreme Court justices have hinted that the case may be dismissed due to lack of standing, as Falcis did not apply for a marriage license himself.[61]

Marriages by the Communist Party of the Philippines

The illegal Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), respectively its armed wing New People’s Army (NPA), does perform same-sex marriages among their members since 2005 in territories under their control.[62]

Discrimination protections

The Magna Carta for Public Social Workers addresses concerns regarding the discrimination of public social workers because of their sexual orientation:

"Section 17. Rights of a Public Social Worker. - Public social workers shall have the following rights:

1.) Protection from discrimination on the grounds of sex, sexual orientation, age, political or religious beliefs, civil status, physical characteristics/disability or ethnicity;

2.) Protection from any form of interference, intimidation, harassment, or punishment, to include, but not limited to, arbitrary reassignment or termination of service, in the performance of his/her duties and responsibilities";[63]

The Magna Carta for Women also provides an insight regarding the state's duties towards maintaining the rights of women, regardless of their sexual orientation:

"The State affirms women's rights as human rights and shall intensify its efforts to fulfill its duties under international and domestic law to recognize, respect, protect, fulfill, and promote all human rights and fundamental freedoms of women, especially marginalized women, in the economic, social, political, cultural, and other fields without distinction or discrimination on account of class, age, sex, gender, language, ethnicity, religion, ideology, disability, education, and status."[64]

In 2001, an anti-discrimination bill banning discrimination based on sexual orientation was unanimously approved by the House but it was stalled in the Senate, and ultimately died.[65]

The only bill directly concerning discrimination against the LGBT community in the Philippines is the Anti-Discrimination Bill, also known as the SOGIE Equality Bill. This bill seeks that all persons regardless of sex, sexual orientation or gender identity be treated the same as everyone else, wherein conditions do not differ in the privileges granted and the liabilities enforced. The bill was introduced by Hon. Kaka J. Bag-ao, the District Representative of the Dinagat Islands on 1 July 2013.[66] A huge bloc of lawmakers, collectively called the Equality Champs of Congress, have been pushing for the full passage of the Anti-Discrimination Bill for 17 years. More than 130 lawmakers backed its complete passage and legislation in the first month of its reintroduction to Congress in 2016 alone.[30]

On 20 September 2017, the Anti-Discrimination Bill (HB 4982)[67] passed its third reading in the House of Representatives, in a unanimous 198-0 vote, under the wing of representatives Kaka Bag-ao, Teddy Baguilat, Tom Villarin, Christopher de Venecia, Geraldine Roman, Arlene Brosas, Carlos Zarate, and House Speaker Pantaleon Alvarez after 17 years of languishing in Congress. It currently awaits a vote in the Senate.[68] Conservative senators Tito Sotto, Manny Pacquiao, and Joel Villanueva have told media that they will block the bill at its current state, while Win Gatchalian, Dick Gordon, Migz Zubiri, Cynthia Villar, Ping Lacson, Gregorio Honasan, Alan Peter Cayetano, Chiz Escudero, Ralph Recto and Koko Pimentel will support it only if drastic limits against LGBT rights are put forth in the bill. Senator Risa Hontiveros, the principal author and backer of the bill, is currently championing the bill's passage in the Senate. The bill in its current form is also backed by senators Nancy Binay, Franklin Drilon, Bam Aquino, Loren Legarda, JV Ejercito, Kiko Pangilinan, Grace Poe, Antonio Trillanes, Sonny Angara,[69] and detained senator Leila de Lima. The version of the bill being championed by Hontiveros is the most comprehensive version in more than 18 years. Conservative senators have been pushing the bill aside since its filing. Both senators de Lima and Cayetano can no longer vote in the Senate due to their current statuses, making the Senate divided on the issue by 12 against, 10 in favor, and 2 immobilized from voting. However, the current division is fluid due to the nature of some conservative senators to vote-by-bloc, which has been seen many times in the past. In January 2018, the bill finally reached the period of amendments after the period of interpolations was deemed finished. It took almost a year before it reached the period of amendments due to conservative senators who vowed to block the bill until the very end. In February and March 2018, senators Sotto, Pacquiao and Villanueva renewed their call against the passage of the SOGIE Equality Bill in any of its possible forms. If the bill is not passed by December 2018, it may never be passed in the 17th Congress as the first half of 2019 is the election campaign season for the May 2019 elections.[54]

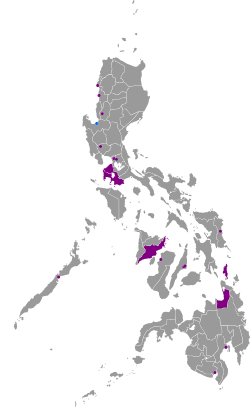

Local government ordinances

Seven provinces prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. These are Albay (2008),[70][71] Agusan del Norte (2014), Batangas (2015), Cavite (2014/18),[72] the Dinagat Islands (2016), Ilocos Sur (2017),[73] and Iloilo (2016).[74][75] The province of Cavite previously prohibited discrimination based on sexual orientation only, but enacted gender identity protections in 2018.

Various cities, barangays and municipalities throughout the Philippines also have non-discrimination ordinances. The cities of Angeles (2013), Antipolo (2015), Bacolod (2013), Baguio (2017), Batangas (2016), Butuan (2016), Candon (2014), Cebu (2012), Davao (2012), General Santos (2016), Iloilo (2018),[76] Mandaluyong (2018),[77] Mandaue (2016), Puerto Princesa (2015), Quezon (2003/14), San Juan (2017),[78] and Vigan (2014) ban sexual orientation and gender identity discrimination.[74][75] 3 barangays also have such ordinances (Bagbag, Greater Lagro and Pansol; all three of which are in Quezon City), as does the municipality of San Julian (2014) in Eastern Samar.

The city of Dagupan enacted an anti-discrimination ordinance in 2010, which includes sexual orientation as a protected characteristic. The anti-discrimination ordinance does not explicitly mention gender identity. However, the terms "sex", "gender" and "other status" could be interpreted as covering it.[79] In 2003, Quezon City approved an ordinance banning discrimination against "homosexuals". In 2014, it amended that ordinance and banned discrimination against anyone on the basis of both sexual orientation and gender identity.

Anti-bullying laws

Sexual orientation and gender identity are included as prohibited grounds of bullying in the Implementing Rules and Regulations (IRR) of the Anti-Bullying Law, approved by Congress in 2013.[80][81]

Living conditions

Religion

Several religious beliefs exists within the country, including Roman Catholicism, the Iglesia ni Cristo and Islam, among many others. These different faiths have their own views and opinions towards the topic of homosexuality.

Roman Catholicism

The Philippines is a predominantly Catholic country with approximately 82.9% of the population claiming to be Roman Catholics.[82] The Roman Catholic Church has been one of the most active religious organizations in the country in opposition to the LGBT community.[83] The Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines firmly states that marriage should only exist between a man and a woman.[84] Also, they have called on individuals and politicians to actively oppose same-sex marriage.[85] They said that individuals should refuse to take part in ceremonies celebrating same-sex relationships and politicians should resist legalizing marriages of same-sex couples.[85] They also stated that "A homosexual union is not and can never be a marriage as properly understood and so-called."[86] However, they also said that "being a homosexual is not a sin. It is a state of a person."[87] The Catholic Church welcomes members of the LGBT community, yet, as stated, gay people should be "welcomed with respect and sensitivity."

Iglesia ni Cristo

The Iglesia ni Cristo adheres to the teachings of the Bible and they denounce those who practice homosexual acts, as they are seen as immoral and wicked. The organization has been called by international human rights organizations as one of the most homophobic religious sects operating in the Philippines.[88] These acts include having sexual affairs and relations with partners of the same sex, cross-dressing, and same-sex marriage.[88] Also, in the Iglesia ni Cristo, men are not allowed to have long hair, for it is seen as a symbol of femininity and should be exclusive to women only. LGBT citizens born from INC families suffer the greatest as their gender existence are branded explicitly as wicked by their own family and the pastor of their locality. Numerous cases have shown that INC members who shift religious beliefs away from INC's beliefs have faced massive backlash from family members, pastors, and other INC members locally and abroad, making it hard for INC members to get away from the church. Hate crimes and forced conversion therapy committed by family members towards INC LGBT teenagers have also surfaced and are backed by the Templo Sentral, the central establishment of the INC church.[88]

Islam

Muslim communities in the Philippines face the challenge of confronting diversity.[89] However, for many Muslims, dealing with homosexuality or transgender issues is a matter of sin and heresy, not difference and diversity. The City of Marawi, which has declared itself as an Islamic City, has passed an ordinance that allows discrimination against LGBT citizens. The ordinance has yet to be challenged in court.[89]

Dayawism

Indigenous belief systems in the country, collectively called dayawism, initially regarded homosexual acts as part of nature, and thus, acceptable, and to some extent, even sacred. Local men dressed up in women’s apparel and acting like women were called, among other things, bayoguin, bayok, agi-ngin, asog, bido and binabae. They were respected leaders and figures of authority: religious functionaries and shamans. However, due to the influential spread of Islam in the south and Christianity in the entire country, such indigenous belief systems were subjugated and thus bore negative views on homosexuality.[90]

Media

Recognized as an important venue for the promotion of issues related to the LGBT community by participants in national dialogue facilitated by the UNDP, the media acknowledges the negative impact of religion concerning the treatment of such issues, where it provides a blanket context that society views homosexuality as negative.[11]

In May 2004, producers of several television programs received a memorandum from the chair of the Movie and Television Review and Classification Board (MTRCB), which warned against positive depictions of lesbian relationships; it was stated in the memo that "lesbian and homosexual relationships are an abnormality/aberration on prime-time TV programs gives the impression that the network is encouraging homosexual relationships."[11]

The lack of sexual orientation and gender identity awareness is emphasized in other circumstances; transphobia is ubiquitous with media practitioners who do not address transgender people in accordance with how they self-identify.[11] At the 2013 Cinemalaya indie awards, transgender actress Mimi Juareza won under the Best Actor category, and in reports, she was referred to repeatedly using the male pronoun.[11] In 2014, the death of Jennifer Laude and the investigation conducted was highly publicized, with practitioners referring to her as Jeffrey "Jennifer" Laude.[91]

Participants in the UNDP-facilitated national dialogue stated that content emphasized a general lack of understanding for sexual orientation and gender identity, such that LGBT stereotypes dominate; there are many gay men hosting programs at radio stations and television networks, but they are limited to covering entertainment shows.[11] There is an apparent lack of representation for lesbians and transgender people.[11] Given their platform, some media personalities have publicly shared their anti-LGBT sentiments; in 2009 newspaper columnist Ramon Tulfo wrote that LGBT people "should not also go around town proclaiming their preferences as if it was a badge of honor."[11]

Beyond mainstream media, which already has a niche for the sector, the Internet has provided LGBT people ways to tell their stories outside the realm of film, television, print, and radio.[11] There are blogs kept, opportunities to connect with others, publications with LGBT sections and a web-based magazine, Outrage, catering to the community.[11]

Views

Ryan Thoreson in his article "Capably Queer: Exploring the Intersections of Queerness and Poverty in the Urban Philippines" did a research on the LGBT community in the Philippines and how it copes with living in the country. He interviewed a total of 80 LGBT informants in order to gather the data.[92] Based on his survey about employment and from what he gathered, he claimed that under a half of the respondents were employed and weekly income mean was only 1514.28 pesos per week.[92] The survey also stated that "less than one-third have stable income and very few enjoyed any kind of benefits",[92] and 75% of its respondents said that they would like to do more wage-earning work.[92]

As for its empowerment section, the survey stated that when the respondents were asked to tell their primary contribution to the household, 45% of them named household chores as their primary contribution, 30% stated giving money or paying the bills, 17.5% provided labor and money, and 7.5% said that they were not expected to contribute anything.[92] As for their privacy, 75% of the respondents said that they had enough privacy and personal space.[92]

In terms of safety and security, Thoreson's journal also provides statistical data in terms of the LGBT community's involvement in crimes as victims. According to the survey he made, 55% of his respondents were harassed on the street, 31.2% were robbed, 25% had been physically assaulted, 6.25% had been sexually assaulted, 5% had survived a murder attempt, and 5% had been blackmailed by the police.[92]

Economy

The LGBT community, although a minority in the economic sphere, still plays an integral role in the growth and maintenance of the economy. LGBT individuals face challenges in employment both on an individual level and as members of a community that is subject to discrimination and abuse. This can be compounded by the weak social status and position of the individuals involved.[11]

A USAID study conducted in 2014, entitled "The Relationship between LGBT Inclusion and Economic Development: An Analysis of Emerging Economies", has shown that countries which have adopted anti-LGBT economic laws have lower GDPs compared to those who do not discriminate against employers/employees based on their sexual orientation.[93] The link between discrimination and the economy is direct, since the discrimination experienced by members of the LGBT community turn them into disadvantaged workers, which can be bad for business. Disadvantaged workers usually practice absenteeism, low productivity, inadequate training and high turnover, which make for higher labor costs and lower profits.[93] According to the USAID study, LGBT people in their sample countries are limited in their freedoms in ways that also create economic harms.[94] This coincides with Emmanuel David's article, Transgender Worker and Queer Value at Global Call Centers in the Philippines, in which he states that "trans- and gender-variant people have always sought paid employment, and they have routinely performed unpaid labor and emotional work".[95] In his article, he focuses on how in the Philippines there is a growing market of trans women looking for employment so they have tried creating their own space as "purple collar" but still face discrimination.

On the other hand, studies have shown that the integration of the LGBT community into the economic system yields a higher income for the country. In a recent USAID study, it is said that a wide range of scholarly theories from economics, political science, sociology, psychology, public health and other social sciences support the idea that full rights and inclusion of LGBT people are associated with higher levels of economic development and well-being for the country.[94] Also, the acceptance of LGBT people within the office environment can lead to higher income for the company since the people do not feel as disadvantaged and as discriminated as before.[94] Another thing is that a better environment for LGBT individuals can be an attractive bargaining chip for countries seeking multinational investments and even tourists, since a conservative climate that keeps LGBT people in the closet and policymakers from recognizing the human rights of LGBT people will hold their economy back from its full potential.[93] Naturally, passing a non-discrimination law will not immediately lead to a sudden boost in the country's economy, although less discrimination should eventually lead to more output.[93]

Politics

Marginalized sectors in society recognised in the national electoral law include categories such as elderly, peasants, labour, youth etc. Under the Philippine Constitution, some 20% of seats in the House of Representatives are reserved. In 1995 and 1997, unsuccessful efforts were made to reform the law so as to include LGBT people. A proponent of this reform was Senate President Pro Tempore Blas Ople who said (in 1997), "In view of the obvious dislike of the ... administration for gay people, it is obvious that the president will not lift a finger to help them gain a sectoral seat."[96]

The Communist Party of the Philippines integrated LGBT rights into its party platform in 1992, becoming the first Philippine political party to do so.[97] The Akbayan Citizens' Action Party was another early party (although a minor one) to advocate for LGBT rights in 1998.

Philippine political parties are typically very cautious about supporting gay rights, as most fall along the social conservative political spectrum. A major political opponent of LGBT rights legislation has been Congressman Bienvenido Abante (6th district, Manila) of the ruling conservative Lakas-CMD party.[98]

The administration of former President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo was called "not just gender insensitive, but gender-dead" by Akbayan Party representative Risa Hontiveros. Rep. Hontiveros also said that the absence of any policy protecting the rights of lesbians, gays, bisexuals and transgender betrays the Government’s homophobia: "this homophobic government treats LGBTs as second-class citizens."[99]

On 11 November 2009, the Philippine Commission on Elections (COMELEC) denied the Filipino LGBT political party Ang Ladlad's petition to be allowed to run in the May 2010 elections, on the grounds of "immorality".[100][101] In the 2007 elections, Ang Ladlad was previously disqualified for failing to prove they had nationwide membership.[102]

On 8 April 2010, the Supreme Court of the Philippines reversed the ruling of COMELEC and allowed Ang Ladlad to join the May 2010 elections.[103][104]

On 17 June 2011, the Philippines abstained from signing the United Nations declaration on sexual orientation and gender identity, which condemns violence, harassment, discrimination, exclusion, stigmatization and prejudice based on sexual orientation and gender identity. However, on 26 September 2014, the country gave a landmark yes vote on a follow-up resolution by the UN Human Rights Council to fight violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI).[105]

The Ang Ladlad is a progressive political party with a primary agenda of combating discrimination and harassment on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity.

LGBT rights at school campuses

University of Santo Tomas

In the 1960s, the first LGBT organization, Tigresa Royal, at the University of Santo Tomas was established. However, the organization dissipated during the martial law era. The organization was never recognized by the university. In 2013, HUE, a new LGBT organization at the university, was formally established. The organization was established by Majann Lazo, the student council president of the Faculty of Arts and Letters, and Noelle Capili, a member of Mediatrix, a university-wide organization for art enthusiasts. Similarly to Tigresa Royal, the university denied HUE recognition as a university organization.[106]

On July 1, 2015, the university ordered numerous organizations to "take down" all rainbow-themed profile pictures of its members on social media after the legalization of same-sex marriage in the United States. The order was defied by numerous students of the university, marking the beginning of the UST Rainbow Protest. In July 2016, various student organizations supported the filing of the SOGIE Equality Bill in the Senate and the House of Representatives.[107][108]

In March 2018, during the passage of the SOGIE Equality Bill in the Philippine House of Representatives, numerous UST student organizations, including the first intersectional feminist organization in the school, UST Hiraya, backed the bill's passage.[109]

On June 21, 2018, statements against the UST LGBT community were circulated on Twitter and Facebook. The statements originally came from the school regent. The tweet noted that the school "understands" LGBT rights, but tasked all presidents of all student organizations at the university to "take down" pro-LGBT statements, especially if those statements involved the words "LGBT" and "Pride Month". The statements garnered massive backlash against the university on social media, with almost 4,000 disapprovals and around 1,100 retweets in less than two days. The order of the school regent was also defied by numerous UST organizations, in continuation of the UST Rainbow Protest.[110][111]

Ateneo University campuses

The Jesuit-run Ateneo de Manila University and its branches throughout the country have been viewed as pro-LGBT since the middle of the 20th century. The university supports the SOGIE Equality Bill, the advancement of the Metro Manila Pride March, sex reassignment surgery (such as in the case of Geraldine Roman), and same-sex marriage.[112][113] The university also has inclusive gender restrooms, a move spearheaded by its Davao campus, which has the largest population of Muslim students. The same campus also held the first pride march in the Davao region.[114][115]

University of the Philippines campuses

All campuses of the University of the Philippines support the SOGIE Equality Bill, same-sex marriage, sex reassignment surgery, and other progressive LGBT causes. The university is home to UP Babaylan, the largest network of LGBT student organizations in the country. All campuses of the university have conducted annual pride marches since their establishment, including Baguio (Cordillera), Pampanga (Central Luzon), Olongapo (Central Luzon), Laguna (Calabarzon), Manila (Metro Manila), Quezon City (Metro Manila), Iloilo (Western Visayas), Davao City (Davao Region), Tacloban (Eastern Visayas) and Cebu (Central Visayas).[116]

University of San Carlos

The Cebu-based University of San Carlos is viewed as "LGBT-friendly", despite its Catholic upbringing. The university has approved various LGBT-related events at the university campus, and even invited Hezekiah Marquez Diaz, the first transwoman in the Philippines to dress as a woman at her graduation. Diaz was a guest speaker at the 6th Carolinian Summit, a leadership summit attended by influencal leaders in Cebu and held at the university.[117][118][119]

University of Mindanao

The campuses of the University of Mindanao outside the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) are seen as "LGBT-friendly", however, the campuses in the ARMM have past cases involving persecution of members of the LGBT community, especially in Marawi, the only city in the Philippines which has an intentional anti-LGBT ordinance. No person has yet to challenge the ordinance in court. In 2012, leaflets and radio broadcasts from unidentified sources were released at the Marawi campus, saying that all LGBT people should move away from the city, if not, all of them will be murdered through "wajib", or a so-called "Muslim obligation".[120] Reports have found that many LGBT students and former students at the university have experienced a variety of harassment and even some near-death experiences. Additionally, many LGBT alumni at the university have been gunned down in the city. One account states that within 4 years, 8 of the closest LGBT friends of a Marawi transwoman were gunned down in the city.[121]

De la Salle University

Campuses of De la Salle University have been viewed as pro-LGBT. The student government of the university has hosted numerous pro-LGBT events including "G for SOGIE" in 2018. In 2011, the Queer Archers' Alliance (QAA) was conceptualized and established at the university.[122] The university has supported the SOGIE Equality Bill, sex reassignment surgery, greater awareness of HIV/AIDS, and other progressive legislation, although some of the university's older employees have contrasting views.[123]

Universidad de Zamboanga

The Universidad de Zamboanga is viewed by many of its students as "pro-LGBT", although cases of hate crimes have surfaced as well.

Saint Louis University

The Baguio-based Saint Louis University is viewed as an "LGBT-friendly" university in the Cordilleras. It supports the SOGIE Equality Bill and it has its own gender-neutral restroom policy.[124]

Lyceum of the Philippines University

The Lyceum of the Philippines University is viewed as "pro-LGBT" and has active student organizations focused on equality, including LPU Kasarian, which successfully lobbied for the university to establish a gender-neutral restroom policy in 2017.[124]

Xavier University

The Jesuit-run Xavier University is viewed as "pro-LGBT". The university supports the SOGIE Equality Bill and sex reassignment surgery.

Polytechnic University of the Philippines

The Polytechnic University of the Philippines is highly viewed as "pro-LGBT". In March 2018, the university itself advocated for LGBT rights, in cooperation with numerous student organizations, including its own LGBT student organization, PUP Kasarianlan.[125] In June 2018, the university had its first ever transgender valedictorian, Ianne Gamboa.[126]

Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Maynila

In September 2013, after a year of fighting for recognition, the University of Manila officially recognized its first and only LGBT student organization, later leading to the first ever pride march at the campus. The recognition of the organization was spearheaded by a coalition of student organizations at the university, ranging from feminist organizations, fraternities, sororities, art organizations, literary organizations, business organizations, and many others.[127]

Eastern Samar State University

In May 2017, the Eastern Samar State University unanimously ruled that gender-neutral restrooms would be implemented as a way to commit to gender equality, becoming the first school in Samar to do so.[128]

Bicol University

In 2013, Bicol University's first LGBT organization, BU MAGENTA, was officially formed and recognized. The organization was backed by numerous faculties of the university. The organization had grown to become the largest LGBT student organization in the Bicol Region by 2018.[129]

Central Luzon State University

The Central Luzon State University is viewed as "LGBT-friendly". The university recognized its first LGBT student organization on the very first year it was established. The university also holds its own gay pageant, where the winner is given the title "Mushroom Fairy".[130][131]

Bulacan State University

The Bulacan State University is home to BulSu Bahaghari, an LGBT student organization and the first established in the province of Bulacan.[132][133]

Silliman University

The Silliman University is viewed as "pro-LGBT". The university has its own LGBT section in its university library, and the library itself organizes LGBT panel activities.[134] It has also recognized many literary works and authors who have advocated for gender equality in the Philippines.[135]

Far Eastern University

The Far Eastern University is viewed as "pro-LGBT". The university allows transgender students to wear clothes reflecting their gender identity on the campus.[136][137][138] The university also accredited Sexuality and Gender Alliance (SAGA), a student-led university-wide organization that fights against any form of abuse or discrimination.[139]

Community

The LGBT community did not begin to organize on behalf of its human rights until the 1990s. Poverty and the political situation in the Philippines, especially the dictatorship, may have made it difficult for the LGBT community to organize. One of the first openly gay people of significance was the filmmaker Lino Brocka.

The first LGBT pride parade in Asia and also the Philippines was co-led by ProGay Philippines and the Metropolitan Community Church Philippines (MCCPH) on 26 June 1994 at the Quezon Memorial Circle. It was organized just a few years after students organized the UP Babaylan group. The pride event was attended by hundreds, and the march coincided with march against the Government's VAT or the value added tax.

Since the 1990s, LGBT people have become more organized and visible, both politically and socially. There are large annual LGBT pride festivals, and several LGBT organizations which focus on the concerns of university students, women and transgender people. There is a vibrant gay scene in the Philippines with several bars, clubs and saunas in Manila as well as various gay rights organizations.

- UP Babaylan,[140] founded in 1992, remains the oldest and largest LGBT student organization in the Philippines.

- Progay-Philippines, founded in 1993, which led the first Gay March in Asia in 1994.[141]

- LAGABLAB, the Lesbian and Gay Legislative Advocacy Network, established in 1999.

- STRAP (Society of Transsexual WOMEN of the Philippines), a Manila-based support group for transgender women, established in 2002.

- Philippine Network of Metropolitan Community Church, a network of LGBT-affirming churches that reclaims spaces for sexuality and spirituality. The first MCC was established in 1991. Member churches are MCC Quezon City,[142] MCC Metro Baguio, MCC Makati, and MCC Marikina.

- PinoyFTM (PFTM or Pioneer Filipino Transgender men Movement), a nationwide organization of Filipino transgender men, established in July 2011.

Military service

Sexual orientation or religion does not exempt citizens from Citizen Army Training (CAT), although some reports do suggest that people who are openly gay are harassed.[143] On 3 March 2009, the Philippines announced that it was lifting its ban on allowing openly gay and bisexual men and women from enlisting and serving in the Philippine Armed Services.[144]

Public opinion

In 2013, a Pew Research Center poll showed that 73% of adult Filipinos agreed with the statement that "homosexuality should be accepted by society," up by nine percentage points from 64% in 2002.[2]

In May 2015, PlanetRomeo, an LGBT social network, published its first Gay Happiness Index (GHI). Gay men from over 120 countries were asked about how they feel about society’s view on homosexuality, how do they experience the way they are treated by other people and how satisfied are they with their lives. The Philippines was ranked 41st with a GHI score of 50.[145]

An opinion poll carried out by the Laylo Research Strategies in 2015 found that 70% of Filipinos strongly disagreed with same-sex marriage, 14% somewhat disagreed, 12% somewhat agreed and 4% strongly agreed.[146] In generalization, the 2015 poll indicated that 84% were against same-sex marriage and 16% were in favor.

In a 2016 poll by ILGA, 52% of Filipinos were against same-sex marriage, 25% were in favor, and 24% were unsure. The poll's results highlighted a huge increase in public support for same-sex marriage in comparison with the 2015 Laylo Research poll.

According to a 2017 poll carried out by ILGA, 63% of Filipinos agreed that gay, lesbian and bisexual people should enjoy the same rights as straight people, while 20% disagreed. Additionally, 63% agreed that they should be protected from workplace discrimination. 27% of Filipinos, however, said that people who are in same-sex relationships should be charged as criminals, while a plurality of 49% disagreed. As for transgender people, 72% agreed that they should have the same rights, 72% believed they should be protected from employment discrimination and 61% believed they should be allowed to change their legal gender.[147]

The Social Weather Survey, conducted between 23 and 27 March 2018, found that 22% of Filipinos supported same-sex civil unions, 61% were against and 16% were undecided.[148][149]

Summary table

| Same-sex sexual activity legal | |

| Equal age of consent | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in employment | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in the provision of goods and services | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in all other areas (incl. indirect discrimination, hate speech) | |

| Same-sex marriage(s) | |

| Recognition of same-sex couples | |

| Stepchild adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Joint adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Gays, lesbians and bisexuals allowed to serve in the military | |

| Right to change legal gender | |

| Conversion therapy banned on minors | |

| Automatic parenthood for both spouses after birth | |

| Access to IVF for lesbians | |

| Commercial surrogacy for gay male couples | |

| MSM allowed to donate blood |

See also

References

- ↑ "CBCP exec: US should respect PHL law regarding same-sex marriage | Pinoy Abroad | GMA News Online". gmanetwork.com. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

- 1 2 3 4 "PH ranks among most gay-friendly in the world | Inquirer Global Nation". globalnation.inquirer.net. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

- ↑ "The Global Divide on Homosexuality". Pew Research Center's Global Attitudes Project. 2013-06-04. Retrieved 2018-01-08.

- 1 2 Salazar, Zeus (1999). Bagong kasaysayan: Ang babaylan sa kasaysayan ng Pilipinas. Philippines: Palimbang Kalawakan. pp. 2–7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Garcia, J. Neil (2009). Philippine gay culture : the last thirty years : binabae to bakla, silahis to MSM. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2009, c2008. pp. 162–163, 166, 170–173, 191, 404. ISBN 9789622099852.

- 1 2 Alcina, Francisco. Historia de las Islas e Indios de Bisayas. pp. 195–209.

- 1 2 Ribadeneira, Marcelo de (1947). History of the Islands of the Philippine Archipelago and the Kingdoms of Great China, Tartary, Cochinchina, Malaca, Siam, Cambodge and Japan. Barcelona: La Editorial Catolica. p. 50.

- ↑ Suicide Ideaton and Suicide Attempt Among Young Lesbian and Bisexual Filipina Women:Evidence for Disparities in the Philippines by Eric Julian Manalastas

- ↑ "Suicide Ideation and Suicide Attempt Among Young Lesbian and Bisexual Filipina Women: Evidence for Disparities in the Philippines" (PDF).

- ↑ Ebook. 1st ed. United Nations. Accessed November 3. International Human Rights Law and Sexual Orientation & Gender Identity. 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 UNDP, USAID. Being LGBT in Asia: the Philippines Country Report. (Bangkok: USAID, 2014)

- ↑ Lewis, Nantawan B (2014). Remembering Conquest: Feminist/Womanist Perspectives on Religion, Colonization, and Sexual Violence. Taylor & Francis. p. 698. ISBN 978-1-317-78946-8.

- ↑ Garcia, J. Neil C. (2008). Philippine Gay Culture: Binabae to Bakla, Silahis to MSM. UP Press. pp. 162–163. ISBN 978-971-542-577-3.

- ↑ Berco, Christian (2005). Social control and its limits; Sodomy, local sexual economies, and inquisitors during Spain’s golden age. The Sixteenth Century Journal. pp. 331–364.

- ↑ Berco, Christian (2009). Producing patriarchy: Male sodomy and gender in early modern Spain. Journal of the History of Sexuality. pp. 351–376.

- ↑ UNDP, USAID (2014). Being LGBT in Asia: The Philippines Country Report. Bangkok. p. 10.

- ↑ Garcia, J. Neil C. (November 2004). "Male homosexuality in the Philippines: a short history" (PDF). IIAS Newsletter. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- 1 2 Martin, Fran (2008). AsiaPacifiQueer: Rethinking Genders and Sexualities. Illinois: University of Illinois Press.

- ↑ Ricordeau, G. au/issue19/ricordeau_review.htm. "Review of "Philippine Gay Culture: Binabae to Bakla, Silahis to MSM"". Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ↑ Garcia, J. Neil C. (2008). Philippine Gay Culture: Binabae to Bakla, Silahis to MSM. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

- ↑ UNDP, USAID (2014). Being LGBT in Asia: The Philippines Country Report. Bangkok.

- ↑ Garcia, J. Neil (2009). Philippine gay culture : the last thirty years : binabae to bakla, silahis to MSM. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2009, c2008. pp. 162–163,166,170–173,191, 404. ISBN 9789622099852

- ↑ Blasius, Mark. We are Everywhere: A Historical Sourcebook of Gay and Lesbian Politics. Mark Blasius. p. 831.

- ↑ Robert Diaz. "Queer Love and Urban Intimacies in Martial Law Manila" Plaridel: A Philippine Journal of Communication, Media and Society 9.2 (2012): 1-19

- ↑ UNDP, USAID (2014). Being LGBT in Asia: The Philippines Country Report. Bangkok. p. 16.

- 1 2 Garcia, J. Neil C. (2008). Philippine Gay Culture: Binabae to Bakla, Silahis to MSM. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press . p.486.

- ↑ Rima Granali, What to do? Ang Ladlad partylist in quandary. inquirer.net. February 16, 2015

- ↑ Asia's oldest Pride March to celebrate love in Luneta Park "Asia's oldest Pride March to celebrate love in Luneta Park" Rappler, June 23, 2015.

- 1 2 "Gay Philippines News & Reports 2003-06". archive.globalgayz.com.

- 1 2 Robert Sawatzky (10 May 2016). "Philippines elects first transgender woman". CNN.

- ↑ Are Pinoys ready for a transgender president?

- ↑ "Gay rights supporters win UN victory to keep UN LGBT expert".

- ↑ DEPED CHILD PROTECTION POLICY Department of Education

- ↑ "Gender-Responsive Basic Education Policy" (PDF).

- ↑ "What is the future of LGBTIQ rights in Southeast Asia?".

- ↑ "LGBT rights supporters rally at SC amid same-sex ma". inquirer.net. June 19, 2018.

- 1 2 "Supreme Court to hear arguments on same-sex marriage Tuesday, June 19, 2018".

- 1 2 Nick Duffy (June 19, 2018). "Philippines Supreme Court hears legal challenge seeking equal marriage". PinkNews.

- ↑ The Revised Penal Code. 1930.

- ↑ "There's a cure for that: Discriminatory Amendment Proposed by Bohol Representative | A European biologist's look at homosexuality in the Philippines". progressph.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

- ↑ "Bohol Sunday Post - February 27, 2011 - Common-law, same-sex marriages abroad invalid in the Philippines". discoverbohol.com. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

- ↑ "HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES | 16th Congress of the Philippines". congress.gov.ph. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

- ↑ "Philippines presidential palace 'respects' same-sex marriage". Gay Star News. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ↑ "SC asked: Allow same-sex marriage in PH". Rappler. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ↑ "'Same sex marriage'". CBCP News. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- 1 2 The Family Code of the Philippines. n.d.

- ↑ "Duterte to consider legalizing same-sex marriage if he becomes president".

- ↑ Duterte backtracks on gay marriage in Philippines BBC News

- ↑ de Guzman, Chad (17 December 2017). "Duterte flip-flops on same-sex marriage, says he supports it". CNN Philippines. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ↑ Tubeza, Philip C. (18 December 2017). "Duterte favors same-sex marriage". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ↑ Dizon, Nikko. "'It's civil union, not marriage'".

- ↑ "House Bill No. 6595" (PDF). House of Representatives of the Philippines. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ↑ Nonato, Vince F. (21 October 2017). "Alvarez files house bill recognizing LGBT unions". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- 1 2 Ager, Maila. "Sotto, Villanueva give same-sex marriage proposal the thumbs down".

- ↑ "Philippines Supreme Court will hear arguments on same-sex marriage". 7 March 2018.

- ↑ News, Ina Reformina, ABS-CBN. "SC sets oral arguments on same-sex marriage".

- ↑ "Ateneo de Manila's student government shows support for the LGBT+ community this Pride Month". pop.inquirer.net. June 18, 2018.

- 1 2 Carmela Fonbuena (18 June 2018). "Philippine lawyer finds unlikely ally in Duterte in fight to legalise gay marriage". The Guardian.

- ↑ "Palace: Too soon for same-sex marriage in the Philippines". Philstar. June 21, 2018.

- ↑ "Senators frown on same-sex marriage". Manila Bulletin. 21 June 2018.

- ↑ Jardeleza lectures marriage equality petitioner: Grave peril case might be dismissed

- ↑ "'Love is love in communist movement'". Inquirer.net. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ↑ Magna Carta for Public Social Workers. n.d.

- ↑ Magna Carta for Women. 2009.

- ↑ "The Philippines' Anti-LGBTQ Discrimination Bill Was Passed With A Stunning Unanimous Vote". Bustle. 21 September 2017.

- ↑ Bag-ao, Kaka. House Bill No. 110 Archived 23 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Congress.gov. 1 July 2013. Accessed 23 October 2015

- ↑ House Bill No. 4982

- ↑ "HOUSE APPROVES LGBT RIGHTS BILL ON FINAL READING". news.abs-cbn.com. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ↑ Comprehensive anti-discrimination law pushed

- ↑ Manila beams with pride, despite debut of anti-gay protesters

- ↑ Human Rights Violations on the Basis of Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, and Homosexuality in the Philippines Coalition Report

- ↑ "Cavite OKs ordinance on LGBT rights".

- ↑ Province of Ilocos Sur passes LGBT anti-discrimination ordinance

- 1 2 "Anti-Discrimination Ordinances".

- 1 2 New LGBTI anti-discrimination laws created in the Philippines GayStarNews

- ↑ "Iloilo City Council approves anti-discrimination ordinance - The Daily Guardian". 12 June 2018.

- ↑ "Philippine City Passes Law Against LGBT Discrimination". 5 June 2018.

- ↑ City of San Juan passes LGBT anti-discrimination ordinance

- ↑ ORDINANCE NO. 1953-2010

- ↑ SOGI included in ‘Anti-Bullying Act of 2013’ IRR

- ↑ ""Just Let Us Be" - Discrimination Against LGBT Students in the Philippines". 21 June 2017.

- ↑ Philippines Demographics Profile 2014 indexmundi.com, June 30, 2015

- ↑ Nina Calleja. CBCP wants anti-discrimination bill cleansed of provisions on gay rights Inquirer.net, December 7, 2011

- ↑ Joel Locsin. Only between man and woman: CBCP stands firm on marriage GMA News Online, June 27, 2015

- 1 2 "Catholic bishops urge followers to oppose same-sex marriage". newsinfo.inquirer.net. Retrieved 2015-11-11.

- ↑ Junk ‘normalization’ of gay unions – CBCP president, cbcpnews.com, August 31, 2015

- ↑ Ryan Leagogo, Archbishop Villegas: Homosexuality is not a sin. inquirer.net, January 12, 2015

- 1 2 3 That's in the Bible! Video. 2012. incmedia.org

- 1 2 Scott Siraj al-Haqq Kugle, Homosexuality in Islam (India: Oneworld Publications, 2010)

- ↑ Male Homosexuality in the Philippines: a short history

- ↑ "Pemberton admits he choked Laude". globalnation.inquirer.net. Retrieved 2015-11-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Thoreson, Ryan (2011-11-01). "Capably Queer: Exploring the Intersections of Queerness and Poverty in the Urban Philippines". Journal of Human Development and Capabilities. 12 (4): 493–510. doi:10.1080/19452829.2011.610783. ISSN 1945-2829.

- 1 2 3 4 M.V. Lee Badgett. The New Case for LGBT Rights: Economics Time, November 25, 2014

- 1 2 3 M.V. Lee Badgett, The Relationship between LGBT Inclusion and Economic Development: An Analysis of Emerging Economies (Los Angeles: The Williams Institute, 2014), 13.

- ↑ Transgender Workers and Queer Value at Global Call Centers in the Philippines

- ↑ THE INTERNATIONAL LESBIAN AND GAY ASSOCIATION Survey: Philippines Archived 2 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Communist Party of the Philippines recognizes LGBT rights, welfare". outrage. 23 June 2014. Retrieved 2014-06-23.

- ↑ "Pro-gay bill not a rights issue - House HR chair - Nation - GMANews.TV - Official Website of GMA News and Public Affairs - Latest Philippine News". GMANews. TV. Retrieved 2011-01-20.

- ↑ "akbayan.org". akbayan.org. Retrieved 2011-01-20.

- ↑ "CHR backs Ang Ladlad in Comelec row". ABS-CBN News. 15 November 2009. Retrieved 2009-12-10.

- ↑ "2010 National and Local Elections". Comelec. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ↑ Aning, Jerome (1 March 2007). "Gay party-list group Ladlad out of the race". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 26 September 2012. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ jpepito78 on Thu, 04/08/2010 - 13:34 (19 January 2010). "SC allows Ang Ladlad to join May poll". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved 2011-01-20.

- ↑ "G.R. No. 190582". Sc.judiciary.gov.ph. Retrieved 2011-01-20.

- ↑ "UN: Landmark Resolution on Anti-Gay Bias". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- ↑ LGBT Org Strives for Recognition in UST

- ↑ Student org takes down ‘gay pride’ profile pics

- ↑ UST online student paper ignites controversy over LGBT flag posting

- ↑ Debunking Some Misconceptions About the SOGIE Equality Bill

- ↑ Sent to me by Thomasian friends: UST just sent an order to its organizations to take down their pro-LGBT statements, because of bad implications.

- ↑ As we celebrate LGBT Pride Month, it is only necessary to touch roots with our LGBT History, the Stonewall Riots and the amazing accomplishments that have been achieved by LGBT activists less than 50 years ago.

- ↑ Get to know PH's first transgender politician

- ↑ Geraldine Roman on being the 1st transgender in Congress, beauty secrets, love, Duterte, Pope Francis & Pacquiao

- ↑ All gender restroom at Ateneo de Davao

- ↑ Davao’s LGBT community holds 1st march

- ↑ UP BABAYLAN

- ↑ LGBT people are human beings too

- ↑ Dear LGBT Millennials

- ↑ Today's CAROLINIAN - January 2013 Issue

- ↑ Dangerous lives: Being LGBT in Muslim Mindanao

- ↑ WHY THE LGBT COMMUNITY IS DREADING A POST-ISIS PHILIPPINES

- ↑ A look at the LGBTQ organizations in DLSU: Queer Archers' Alliance

- ↑ In Focus: LGBT Youth And Advocates Come Together In DLSU For 'G For SOGIE'

- 1 2 Ateneo Isn’t The First to Install Gender-Neutral Restrooms Towards Inclusivity

- ↑ Polytechnic University of the Philippines stresses inclusion in 4th LGBT Pride celebration

- ↑ Kauna-unahang transgender valedictorian ng PUP

- ↑ PLM Propaganda helms first university Pride March in Manila City

- ↑ In Eastern Samar State University, the toilet as battleground to eradicate LGBT discrimination

- ↑ BU Magenta: Raising the rainbow Pride in Bicol

- ↑ CLSU Collegian

- ↑ ‘Educational Camelot’ of the North

- ↑ BulSu Bahaghari

- ↑ LGBTQ+, allies gather for SC oral arguments on marriage equality

- ↑ Library Organizes LGBT Panel in Celebration of Pride Month

- ↑ Literature Major Recognized for Gender Rights Advocacy

- ↑ Gonzales, Cathrine (January 14, 2017). "FEU students can now cross-dress on campus". Rappler.

- ↑ "Daily Diaries: FEU's Move To Make Their Campus More LGBT-Friendly Is Such A Winner". ABS-CBN Lifestyle. Retrieved 2018-07-28.

- ↑ Cajocson, Christian (November–December 2016). "FEU allows cross-dressing, opens Halal food stall". Far Eastern University Advocate. 20: 2.

- ↑ "FEU strengthens diversity, accredits SAGA | Far Eastern University". www.feu.edu.ph. Retrieved 2018-07-28.

- ↑ UP Babaylan

- ↑ Tokyo Lesbian Gay Parade, TLGP in 1994.

- ↑ MCC Quezon City

- ↑ "Military training formatted". Refusingtokill.net. 9 May 2005. Retrieved 2011-01-20.

- ↑ "Philippines ends ban on gays in military | News Story on". 365gay.com. Retrieved 2011-01-20.

- ↑ The Gay Happiness Index. The very first worldwide country ranking, based on the input of 115,000 gay men Planet Romeo

- ↑ "7 in 10 Filipinos oppose same-sex marriage – survey".

- ↑ ILGA-RIWI Global Attitudes Survey ILGA, October 2017

- ↑ First Quarter 2018 Social Weather Survey: 61% of Pinoys oppose, and 22% support, a law that will allow the civil union of two men or two women

- ↑ Only 2 in 10 Filipinos favor same-sex marriage – SWS

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to LGBT in the Philippines. |

- University of the Philippines Babaylan

- Philippines Gay and Lesbian Resources

- Promoting Human Rights and Sexual and Gender Diversity and Equality in the Philippines

- Philippines LGBT Interest Group

- ProGay Philippines

- Outrage Magazine - a publication for the gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex and ally (GLBTQIA) communities in the Philippines; readily available online as a webzine

- Myfemme Magazine - a monthly magazine for women, femmes, butches, F2F, bi-femme & bi-curious

- [Invoice Magazine] - a business and lifestyle magazine for gays and lesbians

- The Philippine Network of Metropolitan Community Churches - an ecumenical Christian church with special ministry for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex and allies