Rizal Park

| Rizal Park | |

|---|---|

| Luneta Park | |

The Rizal Monument in Rizal Park | |

.svg.png) | |

| Type | Urban Park |

| Location | Roxas Boulevard, Ermita, Manila, Philippines |

| Coordinates | 14°34′57″N 120°58′42″E / 14.58250°N 120.97833°ECoordinates: 14°34′57″N 120°58′42″E / 14.58250°N 120.97833°E |

| Area | 58 hectares (140 acres) |

| Created | 1820 |

| Administered by | National Parks Development Committee |

| Website |

rizal |

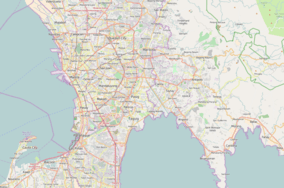

Rizal Park (Filipino: Liwasang Rizal, Spanish: Parque Rizal), also known as Luneta Park or simply Luneta, is a historical urban park in the Philippines. Located along Roxas Boulevard, Manila, adjacent to the old walled city of Intramuros, it is one of the largest urban parks in Asia. It has been a favorite leisure spot, and is frequented on Sundays and national holidays. Rizal Park is one of the major tourist attractions of Manila.

Situated by the Manila Bay, it is an important site in Philippine history. The execution of national hero José Rizal on December 30, 1896 fanned the flames of the 1896 Philippine Revolution against the Kingdom of Spain. The area was officially renamed Rizal Park in his honor, and the monument enshrining his remains serves as the park's symbolic focal point. The Declaration of Philippine Independence from the United States was held here on July 4, 1946 as were later political rallies including those of Ferdinand Marcos and Corazon Aquino in 1986 that culminated in the EDSA Revolution.

Location

Luneta is situated at the northern terminus of Roxas Boulevard. To the east of the boulevard, the park is bounded by Taft Avenue, Padre Burgos Avenue and Kalaw Avenue. To the west is the reclaimed area of the park bounded by Katigbak Drive, South Drive, and the shore of Manila Bay.

History

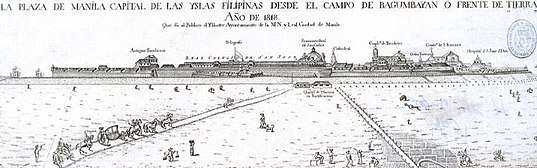

Spanish colonial period

Rizal Park's history began in 1820 when the Paseo de Luneta was completed just south of the walls of Manila on a marshy patch of land next to the beach during the Spanish rule. Prior to the park, the marshy land was the location of a small town called Nuevo Barrio (New Town or Bagumbayan in Tagalog language) that dates back to 1601. The town and its churches, being close to the walled city, were strategically used as cover by the British during their attack. The Spanish authorities anticipated the danger posed by the settlements that immediately surrounded Intramuros in terms of external attacks, yet Church officials advocated for these villages to remain. Because of the part they played during the British Invasion, they were cleared after the short rule of the British from 1762 to 1764.[1] The church of Bagumbayan originally enshrined the Black Nazarene. Because of the order to destroy the village and its church, the image was transferred first to San Nicolas de Tolentino then to Quiapo Church. This has since been commemorated by the Traslación of the relic every January 9, which is more commonly known as the Feast of the Black Nazarene. This is why the processions of January 9 have begun there in the park beginning in 2007.[2] After the clearing of the Bagumbayan settlement, the area later became known as Bagumbayan Field where the Cuartel la Luneta (Luneta Barracks), a Spanish Military Hospital (which was destroyed by one of the earthquakes of Manila), and a moat-surrounded outwork of the walled city of Manila, known as the Luneta (lunette) because of its crescent shape.[3][4]

West of Bagumbayan Field was the Paseo de la Luneta (Plaza of the Lunette) named after the fortification, not because of the shape of the plaza which was a long 100-by-300-metre (330 ft × 980 ft) rectangle ended by two semicircles. It was also named Paseo de Alfonso XII (Plaza of Alfonso XII), after Alfonso XII, King of Spain during his reign from 1874 to 1885.[5] Paseo de la Luneta was the center of social activity for the people of Manila in the early evening hours. This plaza was arranged with paths and lawns and surrounded by a wide driveway called "La Calzada" (The Road) where carriages circulate.[3][4]

Execution of Gómez, Burgos and Zamora

During the Spanish period from 1823 to 1897 most especially in the latter part, the place became notorious for public executions. A total of 158 political enemies of Spain were executed in the park.[4] On February 17, 1872, three Filipino priests, Mariano Gómez, José Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora, collectively known as Gomburza, were executed by garrote, accused of subversion arising from the 1872 Cavite mutiny.[6]

American colonial period

Rizal Monument

The bronze-and-granite Rizal monument is among the most famous sculptural landmarks in the country. It is almost protocol for visiting dignitaries to lay a wreath at the monument. Located on the monument is not merely the statue of the national hero, but also his remains.[7]

On September 28, 1901, the United States Philippine Commission approved Act No. 243, which would erect a monument in Luneta to commemorate the memory of José Rizal, Filipino patriot, writer and poet.[8] The committee formed by the act held an international design competition between 1905 and 1907 and invited sculptors from Europe and the United States to submit entries with an estimated cost of ₱100,000 using local materials.[9]

The first-prize winner was Carlos Nicoli of Carrara, Italy for his scaled plaster model titled “Al Martir de Bagumbayan” (To the Martyr of Bagumbayan) besting 40 other accepted entries. The contract though, was awarded to second-placer Swiss sculptor named Richard Kissling for his “Motto Stella” (Guiding Star).

After more than twelve years of its approval, the shrine was finally unveiled on December 30, 1913 during Rizal’s 17th death anniversary. His poem "Mi Ultimo Adios" ("My Last Farewell") is inscribed on the memorial plaque. The site is continuously guarded by ceremonial soldiers of Philippine Marine Corps’ Marine Security and Escort Group[10]

National Government Center

In 1902,[11] William Taft commissioned Daniel Burnham, architect and city planner, to do the city plan of Manila. Government buildings will have Neo-classical edifices with Greco-Roman columns. Burnham chose Luneta as the location of the new government center. A large Capitol building, which was envisioned to be the Philippine version of the Washington Capitol, was to become its core. It was to be surrounded by other government buildings, but only two of those buildings were built around Agrifina Circle, facing each other. They are the Department of Agriculture (now the National Museum of Anthropology) and the Department of Finance (now the Department of Tourism and soon to be the National Museum of Natural History). These two buildings were completed before the Second World War.[12]

The Historical Luneta Park The Luneta or Rizal Park is famous because it has been the spot where the country’s national hero Jose Rizal was executed in front of the Filipino crowd during the Spanish colonial era.

The history of the park began in the early 1800’s under the Spanish rule. The name “Luneta” was derived from the word “Luna” because the area was shaped like a moon. Before, the former name of the place was Bagumbayan (new town) and was later named Luneta

Luneta National Park

In August 1954, President Ramon Magsaysay created the Jose Rizal National Centennial Commission to organize and manage the celebrations for the centennial of José Rizal’s birth.[13] Its plans include building a grand monument of José Rizal and the Rizal Memorial Cultural Center that would contain a national theater, a national museum, and a national library at the Luneta.[14] The site was declared a national park on December 19, 1955 by virtue of Proclamation No. 234 signed by President Magsaysay.[15] The Luneta National Park spans an area of approximately 16.24 hectares (40.1 acres) covering the area surrounding the Rizal Monument. The Commission of Parks and Wildlife (now Biodiversity Management Bureau) managed the site upon its establishment as a protected area.

In 1957, President Carlos P. Garcia issued Proclamation No. 470 transferring the administration of the national park to the Jose Rizal National Centennial Commission.[16] In 1961, in commemoration of Rizal's birth centennial, the National Library was inaugurated at the park.[14] Its management was then handed over to the National Parks Development Committee, an attached agency of the Department of Tourism, created in 1963 by President Diosdado Macapagal.[17][18] In 1967, the Luneta National Park was renamed to Rizal Park with the signing of Proclamation No. 299 by President Ferdinand Marcos.[19]

Philippine Centennial

On June 12, 1998, the park hosted many festivities which capped the 1998 Philippine Centennial, the event commemorating a hundred years since the Declaration of Independence from Spain and the establishment of the First Philippine Republic. The celebrations were led by then President Fidel V. Ramos.[20]

2011 renovations

Rizal Park underwent renovations by the National Parks Development Committee (NPDC) aimed at restoring elements of the park. The plans included the rehabilitation of the old musical dancing fountain located on the 40 m × 100 m (130 ft × 330 ft) pool, which is the geographical center of the park. The fountain, which is set for inauguration on December 16, 2011, is handled by German-Filipino William Schaare, the same person who built the original fountain in the 1960s. Restoration also included the Flower Clock which was set for inauguration on the 113th Philippine Independence day; the Noli Me Tangere Garden and the Luzviminda Boardwalk, for the 150th birthday celebration of Jose Rizal.[21]

Notable events in the park

- Various mass protests were held during 1986 as opposition to the government of Ferdinand Marcos. This culminated into the People Power Revolution.

- January 15, 1995. The closing Mass of the X World Youth Day 1995 was held here attended by more than 5 million people. This is the record gathering of the Roman Catholic Church.

- June 12, 1998. The Philippine Centennial Celebrations featured a Grand Centennial Parade culminating in a fireworks display emanating from ships in Manila Bay that was the most expensive ever produced in the country at the time. Rizal Park had over five million celebrating the one hundredth anniversary of the Philippine Declaration of Independence.

- December 31, 1999 – January 1, 2000. The turn-of-the-century celebration was held here attended by more than 5 million people.

- November 27, 2005. Rizal Park was the venue of the opening ceremony for the 2005 Southeast Asian Games at the Quirino Grandstand. It was held at an open-air park instead of a stadium, a historic first for a Southeast Asian games' opening ceremony. It was again used on December 5, 2005 for the games' closing ceremony.

- August 23, 2010. The park was the site of the 11-hour hostage crisis where a Hong Thai Travel Services tour group on a coach was hijacked by Rolando Mendoza, causing casualties and injuries.

- August 22–26, 2013. The Million People March was held in the park, and other different locations, to protest against the improper use of Priority Development Assistance Fund.

- January 18, 2015. The concluding mass of the Papal visit of Pope Francis was held here attended by more than 6 million people, making it the largest papal gathering in history.[22]

Recurring events

- The annual Independence Day (June 12), Rizal Day (December 30) and New Year's Eve (December 31) celebrations are held at the park.

- The park is the traditional end of the Marlboro Tour (now known as the Tour de Filipinas), the national road bicycle racing event every April or May. Recently, the tour has ended in Baguio.

- The park is also the host of the National Milo Marathon.

- The parade of floats for the Metro Manila Film Festival is annually held every Christmas. Recently, the cities and towns in Metro Manila have begun rotating the hosting of the parade.

- Presidential inaugurations are usually held in the park every June 30, six years starting from 1992.

Park layout

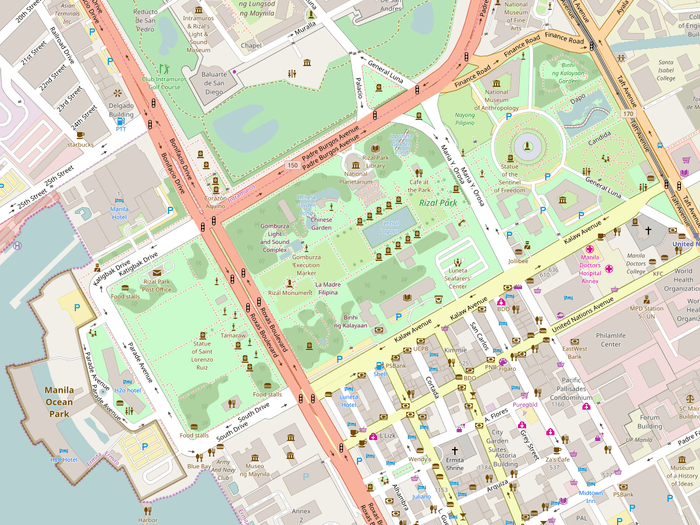

The park is divided into three sections beginning with the 16-hectare (40-acre) Agrifina Circle adjoining Taft Avenue, where the Department of Tourism and the National Museum of Anthropology (formerly the Department of Agriculture and the Department of Finance respectively) are located, is the Northeastern section; followed by the 22-hectare (54-acre) park proper that extends down to Roxas Boulevard is the Central Section; and terminating at Southwestern section which includes Burnham Green, a 10-hectare (25-acre) open field, the Quirino Grandstand and the Manila Ocean Park along Manila Bay.

| N W  S | ||||

| Northeastern side | ||||

| Northwestern side | Southeastern side | |||

National Museum of Anthropology |

Agrifina Circle and the Sentinel of Freedom |

_Facade_-_Front_View.jpg) National Museum of Natural History | ||

Japanese Garden |

Rizal Monument |

National Library of the Philippines | ||

Intramuros |

National Historical Commission of the Philippines | |||

.jpg) Manila Hotel |

Quirino Grandstand |

Museo Pambata, formerly the Manila Elks Club | ||

| Southwestern side | ||||

Activities

The park is home to various Kali/Eskrima/Filipino Martial Arts (FMA) groups. Every morning, especially on Sundays, Eskrimadors, or Eskrima practitioners can be seen at the Luneta. Even up to the present, stickfighting duels are still very common, albeit in a friendly atmosphere. Various physical fitness groups doing aerobics at the park are also present on weekends.

Like-minded individuals from all walks of life who have a knack or penchant for quizzes and trivia (any trivial or academic questions under the sun) also gravitates for graveyard Trivia Meetups at the Luneta Park on weekends, especially on Saturday from dusk till dawn along the promenade of Japanese Garden and Chess Plaza. Kite flying is also seen in the park area.

Gardens

- Children's Playground, the section of the park built for kids, is located at the southeastern corner of the Rizal Park. The playground was also renovated in 2011.[21]

- Chinese Garden. An ornate Chinese-style gate, carved with swirling dragons, leads you into this whimsical garden which looks like it has been transported from old Peking. Along the lagoon constructed to simulate a small lake, are pagodas and gazebos that are set off by red pillars and green-tiled roofs and decorated with a profusion of mythical figures.

- Japanese Garden. The gardens were built to promote friendship between Japan and the Philippines. Inside is nice place for pleasant walks around the Japanese style gardens, lagoon and bridge.

- Noli me Tangere Garden, recently unveiled, It features the Heidelberg fountain where Rizal used to drink from when he was staying in Germany. It was donated as a symbol of Filipino-German friendship, The bust of Ferdinand Blumentritt can be found at the garden.

- Orchidarium and Butterfly Pavilion, established in 1994, was a former parking lot developed into a one-hectare rainforest-like park. The Orchidarium showcases Philippines' rich collection of orchid species and butterflies. The pavilion is also a favorite venue for weddings.

Event venues

- Open-air Auditorium, Designed by National artist for architecture, Leandro Locsin,It features performances provided for free to the general public by the National Parks Development Committee, Department of Tourism and the National Broadcasting Network. Free entertainment are also provided elsewhere in the park.[23] Featured shows are a mix of performances from dance, theatre, to musical performances by local and foreign artists. This is also the venue for the Cinema in the Open-Air, which provides free showing of critically acclaimed films.

- Quirino Grandstand, Originally called grand Independence Grandstand. It was designed by architect Juan M. Arellano, in preparation for the proclamation of Independence on July 4, 1946, and to avoid overcrowding in front of the Legislative Building during the inauguration of the Third Philippine Republic. It was designed in Neoclassical style. However, in 1949 Federico Illustre, chief architect at the Bureau of Public Works, modify the some designs of Arellano. It was completed on the reclaimed area along Manila Bay where President Elpidio Quirino was sworn in after winning the presidential election. Since then, newly elected Presidents of the Philippines traditionally take their oath of office and deliver their inaugural address to the nation in the grandstand, which was later renamed after President Quirino. Many important political, cultural and religious events in the post war era have been held here.

- Parade grounds and the Burnham Green, Parade grounds is a popular venue for fun run, races, motorcades and parades. The Burnham Green, named after American architect Daniel Burnham is a large open space in front of the Quirino grandstand, Designed to accommodate large crowd gatherings at the park, It also serves as picnic grounds and venue for different sports activities. The Narra tree planted by Pope Paul VI and the bronze statue of San Lorenzo Ruiz that was given by Pope John Paul II can be found in this area.

- Valor's Hall/Bulwagan ng Kagitingan, situated at the light and sound complex, Its artistic landscape and design made it one of the top-pick venues for event and cocktail receptions.

Educational establishments

- National Planetarium

- National Museum of Anthropology, on the building north of Agrifina Circle, are the Anthropology and Archeology collections of the National Museum of the Philippines.

- National Library of the Philippines is the country's premier public library. The library has a history of its own and its rich Filipiniana collections are maintained by the librarians to preserve the institution as the nations fountain of local knowledge and source of information for thousands of students and everyday users in their research and studies.

- National Museum of Fine Arts, located on the northeastern tip of Rizal Park, is an art museum of the National Museum of the Philippines.

- Manila Ocean Park is an oceanarium located in the westernmost part of Luneta behind the Quirino Grandstand and along Manila Bay. The complex opened on March 1, 2008.

Artworks and monuments

- Artist's Haven/Kanllungan ng Sining, A site of artistic and natural artworks, It houses the gallery run by the Arts Association of the Philippines (AAP), in collaboration with the NDPC.

- Artworks in the Park, The Rizal park features different artworks of some renowned Filipino artists:

- Dancing Rings, A replica of Joe Datuin's Dancing Rings, The original sculpture is the Grand Prize winner of the 2008 International Olympic Committee Sports and Arts Contest in Lausanne, Switzerland.

- The New Filipino/Ang Bagong Pinoy, A sculpture by Joe Dautin, It features intertwined rings resemble a human figure that represents a new Filipino.

- Ang Pagbabago (The Change) Mosaic Murals, It represents the Filipino ideals of peace, love, unity and prosperity. It serves as a call to national renewal and change.

- Diorama of Rizal's Martyrdom. On an area north of Rizal monument stands a set of statues depicting Rizal's execution, situated on the spot where he was actually martyred, contrary to popular belief that the monument is the spot where he was executed. In the evenings, a Light & Sound presentation titled "The Martyrdom of Dr. Jose Rizal", features a multimedia dramatization of the last poignant minutes of the life of the national hero. Rizal's poem Mi Ultimo Adios engraved in a black granite, can be also be found here.[24]

- Filipino-Korean Soldier Monument. This monument of two Filipino soldiers aiding a Korean soldier is dedicated to the Filipino combat soldiers who fought with the Korean troops during the Korean War.[25]

- Soul waves, It represents sea waves as a tribute to Filipino who died during the World War II, It is placed in the park by Korea, as a sign of mutual respect.

- The Flower Clock, features a clock on a flower bed. A feature of the park since the 1960s, it was restored in 2011. The clock's hand was sculpted by Filipino Artist, Jose Datuin.

- The Gallery of Heroes, is a row of bust sculpture monuments of historical Philippine Heroes. There are 2 rows on both sides of the Central Lagoon, one row on the North Promenade and another row on the South Promenade

- La Madre Filipina. First unveiled in 1921, the statue was part of a set of four sculptures that depicted Filipina motherhood which adorned the pillars of Jones Bridge. After World War II, only three of these statues survived and were relocated elsewhere; the other two were relocated to the Court of Appeals complex.

- Relief map of the Philippines is a giant raised-relief map of the country, including the Scarborough Shoal, Kalayaan, and eastern part of Sabah, in the middle of a small man-made lake.

- Statue of the Sentinel of Freedom (or the Lapu-Lapu Monument). The monument was a gift from the people of Korea as appreciation and to honor the memory of freedom-loving Filipinos who helped during the Korean War in the early 1950s (as inscribed in the plaque). Lapu-Lapu was a native Visayan chieftain in Mactan, Cebu and representative of the Sultan of Sulu, and is now known as the first native of the archipelago to resist Spanish colonization. He is retroactively regarded as the first national hero of the Philippines. On the morning of April 27, 1521, Lapu-Lapu and the men of Mactan, armed with spears and kampilan, faced Spanish soldiers led by Portuguese captain Ferdinand Magellan in what would later be known as the Battle of Mactan. Magellan and several of his men were killed.

Other features

- Independence Flagpole, standing at 105 feet (32 m), is the highest flagpole in the Philippines. On this spot in front of Rizal Monument, at 9:15am July 4, 1946, the full independence of the Republic of the Philippines was proclaimed as authorized by the United States President Harry S. Truman. As of August 2013, the flagpole was restored and increased its height to 150 feet (46 m). The government is expected to spend 7.8 million pesos, in preparation for the centennial of Rizal Monument[26]

- Kilometre Zero is located within the Park on Roxas Boulevard, in front of the Rizal Monument. It serves as the point from which all road distances from Manila are measured.[27]

- Musical Dancing Fountain, Deemed as the biggest and most vibrant dancing fountain in the country, The central lagoon present a show with waters soaring up to 88 feet., fireballs, exploding water rockets and peacock spray water screen.

Security

In 2012, 30 high-definition closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras were installed to make the area safer for local and foreign tourists.[28] The National Parks Development Committee have stationed police and security officers in the key places in the park for added security.[21]

In popular culture

- The Amazing Race 5, the fifth installment of the American Reality TV show, featured the Rizal Monument on Leg 12 as Route Marker.

- The Port Malaya patch in Ragnarok Online, a massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMOPPG), features a replica of the Rizal Monument as one of the town's attractions.[29]

Gallery

The park during the 119th Rizal Day commemoration

The park during the 119th Rizal Day commemoration Dancing Rings sculpture

Dancing Rings sculpture- The entrance arch to the Chinese garden

- Gomburza execution site

.jpg) Carabao sculpture

Carabao sculpture Life-size statues at Rizal's execution site

Life-size statues at Rizal's execution site

Rizal Parks elsewhere

Like Rizal Avenues, most Philippine towns and cities has a Rizal Park (or a Plaza Rizal), usually its central square. This is also where its Rizal monument is located. Seattle also has its own Rizal Park.

See also

References

- ↑ Joaquin, Nick (1990). Manila My Manila. Manila: The City of Manila.

- ↑ "Trivia: 11 things you didn't know about the Black Nazarene". InterAksyon.com. Archived from the original on November 4, 2016. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- 1 2 (1911–12). "The Century Magazine", p.237-249. The Century Co., NY, 1912.

- 1 2 3 "History – Spanish Period" Archived September 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.. Rizal Park. Retrieved on October 7, 2011.

- ↑ "Manila and suburbs, 1898". University of Texas in Austin Library. Retrieved on October 7, 2011.

- ↑ Jernegan, Prescott Ford (1995). "A Short History of the Philippines", p.252. New York: D. Appleton and Company.

- ↑ Vicente, Rafael L. (2005). "The Promise of the Foreign Nationalism and the Technics of Translation in the Spanish Philippines", p. 36. Duke University Press.

- ↑ Division of Insular Affairs, War Department (1901). "Public Laws and Resolutions Passed by the United States Philippine Commission", p.689. Washington: Government Printing Office.

- ↑ (1905–06). "Proposed Monuments and Monuments News", p.40. Granite, Marble and Bronze Magazine Vol. 15.

- ↑

- ↑ http://www.visitmyphilippines.com/index.php?title=CityofManila&func=all&pid=2557

- ↑ Torres, Cristina Evangelista (2014). “The Americanization of Manila, 1898 – 1921”, p.169. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

- ↑ "Executive Order No. 52, s. 1954". Official Gazette (Philippines). Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- 1 2 "The Centenary of the Rizal Monument". Official Gazette (Philippines). Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Proclamation No. 234, s.1955". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Proclamation No. 470, s. 1957". Official Gazette (Philippines). Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Executive Order No. 30, s. 1963". Official Gazette (Philippines). Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ↑ "National Parks Development Committee". National Parks Development Committee. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Proclamation No. 299, s. 1967". Official Gazette (Philippines). Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ↑ Alcazaren, Paolo (July 10, 2010). "Grandstands and great public places". Philstar. Retrieved on 2011-02-28.

- 1 2 3 Mejia-Acosta, Iris (May 25, 2011). "Luneta Celebrates Rizal's 150th Birthday with a Fresh Look". Pinay Ads.

- ↑ Hegina, Aries Joseph (January 18, 2015). "MMDA: 6M Filipinos attended Pope Francis' Luneta Mass, papal route". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- ↑ "Events" Archived November 1, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.. Rizal Park – NPDC. Retrieved on March 21, 2013.

- ↑ "The Martyrdom of Dr. Jose Rizal" Archived November 30, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.. Rizal Park – NPDC. Retrieved on October 8, 2011.

- ↑ The Rizal Park 2012 brochure. Department of Tourism.

- ↑

- ↑ Maranga, Mark Anthony (2010). "Kilometer Zero: Distance Reference of Manila". Philippines Travel Guide. Retrieved on February 28, 2011.

- ↑ "CCTV cameras seen to make Manila's Luneta Park safer". Yahoo! Philippines. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ↑ Otakultura.com (2011). "Malaya Map Revealed!" Archived October 3, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved on September 1, 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rizal Park. |