Right-wing populism

Right-wing populism is a political ideology which combines right-wing politics and populist rhetoric and themes. The rhetoric often consists of anti-elitist sentiments, opposition to the system and speaking for the common people.

In Europe, right-wing populism is an expression used to describe groups, politicians and political parties generally known for their opposition to immigration,[1] mostly from the Islamic world[2] and in most cases Euroscepticism.[3] Right-wing populism in the Western world is generally—though not exclusively—associated with ideologies such as neo-nationalism,[4][5] anti-globalization,[6] nativism,[7][8] protectionism[9] and opposition to immigration.[10] Anti-Muslim ideas and sentiments serve as the "great unifiers" among right-wing political formations throughout Western Europe.[11] Traditional right-wing views such as opposition to an increasing support for the welfare state and a "more lavish, but also more restrictive, domestic social spending" scheme is also described under right-wing populism and is sometimes called "welfare chauvinism".[12][13][14]

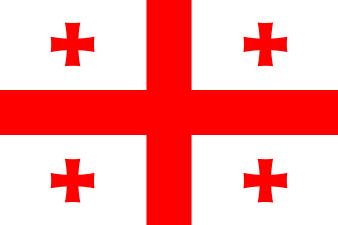

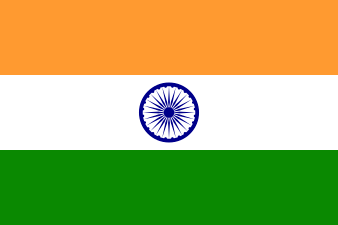

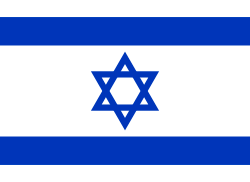

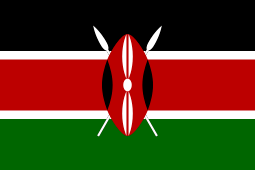

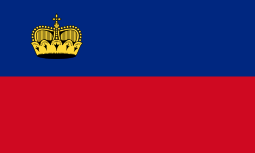

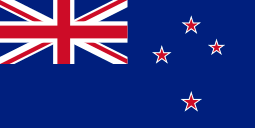

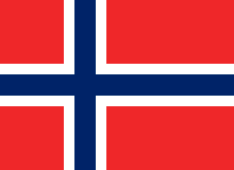

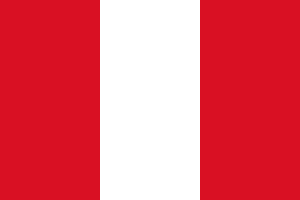

From the 1990s, right-wing populist parties became established in the legislatures of various democracies, including Australia, Brazil, Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Romania and Sweden; and they entered coalition governments in Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Chile, Finland, Greece, Italy,[15] Israel, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Slovakia and Switzerland; and majority governments in India, Turkey, Hungary and Poland. Although extreme right-wing movements in the United States have been studied separately, where they are normally called "radical right", some writers consider them to be a part of the same phenomenon.[16] Right-wing populism in the United States is also closely linked to paleoconservatism.[17] Right-wing populism is distinct from conservatism, but several right-wing populist parties have their roots in conservative political parties.[18] Other populist parties have links to fascist movements founded during the interwar period when Italian, German, Hungarian, Spanish and Japanese fascism rose to power.

Since the Great Recession,[19][20][21] right-wing populist movements such as the National Front in France, the Northern League in Italy, the Party for Freedom in the Netherlands and the UK Independence Party began to grow in popularity,[22][23] in large part because of increasing opposition to immigration from the Middle East and Africa, rising Euroscepticism and discontent with the economic policies of the European Union.[24] U.S. President Donald Trump's 2016 political views have been summarized by pundits as right-wing populist[25] and nationalist.[26][27]

Definition

Classification of right-wing populism into a single political family has proved difficult and it is not certain whether a meaningful category exists, or merely a cluster of categories since the parties differ in ideology, organization and leadership rhetoric. Unlike traditional parties, they also do not belong to international organizations of like-minded parties, and they do not use similar terms to describe themselves.[28]

Scholars use terminology inconsistently, sometimes referring to right-wing populism as "radical right"[29] or other terms such as new nationalism.[30] Pippa Norris noted that "standard reference works use alternate typologies and diverse labels categorising parties as 'far' or 'extreme' right, 'new right', 'anti-immigrant' or 'neofascist', 'antiestablishment', 'national populist', 'protest', 'ethnic', 'authoritarian', 'antigovernment', 'antiparty', 'ultranationalist', 'neoliberal', 'right-libertarian' and so on".[31]

By country

Piero Ignazi divided right-wing populist parties, which he called "extreme right parties", into two categories: he placed traditional right-wing parties that had developed out of the historical right and post-industrial parties that had developed independently. He placed the British National Party, the National Democratic Party of Germany, the German People's Union and the former Dutch Centre Party in the first category, whose prototype would be the disbanded Italian Social Movement; whereas he placed the French National Front, the German Republicans, the Dutch Centre Democrats, the former Belgian Vlaams Blok (which would include certain aspects of traditional extreme right parties), the Danish Progress Party, the Norwegian Progress Party and the Freedom Party of Austria in the second category.[32][33]

Right-wing populist parties in the English-speaking world include the UK Independence Party and Australia's One Nation.[34] The U.S. Republican Party and Conservative Party of Canada include right-wing populist factions.

Australia

The main right-wing populist party in Australia is One Nation, led by Pauline Hanson, Senator for Queensland.[35] One Nation typically supports the governing Coalition.[36]

Other parties represented in the Australian Parliament with right-wing populist elements and rhetoric include the Australian Conservatives, led by Cory Bernardi, Senator for South Australia,[37] the libertarian Liberal Democratic Party, led by David Leyonhjelm, Senator for New South Wales,[38] and Katter's Australian Party, led by Queensland MP Bob Katter.[39] The three parties form a voting bloc in the Australian Senate.[40]

Some figures within the Liberal Party of Australia, which is part of the Coalition, have been described as right-wing populists, including former Prime Minister Tony Abbott[41] and Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton.[42]

Canada

Canada has a history of right-wing populist protest parties and politicians, most notably in Western Canada due to Western alienation. The highly successful Social Credit Party of Canada consistently won seats in British Columbia, Alberta, and Saskatchewan, but fell into obscurity by the 1970s. The Reform Party of Canada led by Preston Manning was another very successful right-wing populist formed as a result of the policies of the centre-right Progressive Conservative Party of Canada which alienated many Blue Tories. The two parties ultimately merged into the Conservative Party of Canada.

In recent years, right-wing populist elements have existed within the Conservative Party of Canada and mainstream provincial parties, and have most notably been espoused by Ontario MP Kellie Leitch; businessman Kevin O'Leary; the leader of the Coalition Avenir Québec, François Legault; the former Mayor of Toronto, Rob Ford; and his brother, Ontario Premier Doug Ford.[43][44][45][46]

In August 2018, Conservative MP Maxime Bernier left the party, and the following month he founded the People's Party of Canada, which has been described as a "right of centre, populist" movement.[47]

European countries

.png)

Right-wing populists represented in the parliament

Right-wing populists involved in the government

Right-wing populists appoint prime minister

Senior European Union diplomats cite growing anxiety in Europe about Russian financial support for far-right and populist movements and told the Financial Times that the intelligence agencies of "several" countries had stepped up scrutiny of possible links with Moscow.[48] In 2016, the Czech Republic warned that Russia tries to "divide and conquer" the European Union by supporting rightwing populist politicians across the bloc.[49]

Austria

The Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ) established in 1955 by a former Nazi functionary claims to represent a "Third Camp" (Drittes Lager), beside the Socialist Party and the social Catholic Austrian People's Party. It succeeded the Federation of Independents founded after World War II, adopting the pre-war heritage of German nationalism. Though it did not gain much popularity for decades, it exercised considerable balance of power by supporting several federal governments, be it right-wing or left-wing, e.g. the Socialist Kreisky cabinet of 1970 (see Kreisky–Peter–Wiesenthal affair).

From 1980, the Freedom Party adopted a more liberal stance. Upon the 1983 federal election, it entered a coalition government with the Socialist Party, whereby party chairman Norbert Steger served as Vice-Chancellor. The liberal interlude however ended, when Jörg Haider was elected chairman in 1986. By his down-to-earth manners and patriotic attitude, Haider re-integrated the party's nationalist base voters. Nevertheless, he was also able to obtain votes from large sections of population disenchanted with politics by publicly denouncing corruption and nepotism of the Austrian Proporz system. The electoral success was boosted by Austria's accession to the European Union in 1995.

Upon the 1999 federal election, the Freedom Party (FPÖ) with 26.9% of the votes cast became the second strongest party in the National Council parliament. Having entered a coalition government with the People's Party, Haider had to face the disability of several FPÖ ministers, but also the impossibility of agitation against members of his own cabinet. In 2005, he finally countered the FPÖ's loss of reputation by the Alliance for the Future of Austria (BZÖ) relaunch in order to carry on his government. The remaining FPÖ members elected Heinz-Christian Strache chairman, but since the 2006 federal election both right-wing parties have run separately. After Haider was killed in a car accident in 2008, the BZÖ has lost a measurable amount of support.

The FPÖ regained much of its support in subsequent elections. Its candidate Norbert Hofer made it into the runoff in the 2016 presidential election, though he narrowly lost the election. After the 2017 legislative elections, the FPÖ formed a government coalition with the Austrian People's Party.

Belgium

Vlaams Blok, established in 1978, operated on a platform of law and order, anti-immigration (with particular focus on Islamic immigration) and secession of the Flanders region of the country. The secession was originally planned to end in the annexation of Flanders by the culturally and linguistically similar Netherlands until the plan was abandoned due to the multiculturalism in that country. In the elections to the Flemish Parliament in June 2004, the party received 24.2% of the vote, within less than 2% of being the largest party.[50] However, in November of the same year, the party was ruled illegal under anti-racism law for, among other things, advocating schools segregated between citizens and immigrants.[51]

In less than a week, the party was re-established under the name Vlaams Belang, with a near-identical ideology. It advocates for immigrants wishing to stay to adopt the Flemish culture and language.[52] Despite some accusations of antisemitism from Belgium's Jewish population, the party has demonstrated a staunch pro-Israel stance as part of its opposition to Islam.[53] With 18 of 124 seats, Vlaams Belang lead the opposition in the Flemish Parliament[54] and also have 11 of the 150 seats in the Belgian House of Representatives.[55]

Cyprus

The ELAM (National People's Front) (Εθνικό Λαϊκό Μέτωπο) was formed in 2008 on the platform of maintaining Cypriot identity, opposition to further European integration, immigration and the status quo that remains due to Turkey's invasion of a third of the island (and the international community's lack of intention to solve the issue).

Denmark

In the early 1970s, the home of the strongest right-wing-populist party in Europe was in Denmark, the Progress Party.[56] In the 1973 election, it received almost 16% of the vote.[57] In the following years, its support dwindled away, but was replaced by the Danish People's Party in the 1990s, which has gone on to be an important support party for the governing Liberal-Conservative coalition in the 2000s (decade).[58] The Danish People's Party is the largest and most influential right-wing populist party in Denmark today. It won 37 seats in the Danish general election, 2015[59] and became the second largest party in Denmark. The Danish People's Party advocates immigration reductions, particularly from non-Western countries, favor cultural assimilation of first generation migrants into Danish society and are opposed to Denmark becoming a multicultural society.

Additionally, the Danish People's Party's stated goals are to enforce a strict rule of law, to maintain a strong welfare system for those in need, to promote economic growth by strengthening education and encouraging people to work and in favor of protecting the environment.[60] In 2015, The New Right was founded,[61] but they have not yet participated in an election.

Finland

In Finland, the Finns Party is the main right-wing populist party and the second largest party in Finland. In 2017, 19 of the 37 MPs from the party split and founded Blue Reform.

France

In France, the main right-wing populist party is the National Front. Since Marine Le Pen's election at the head of the party in 2011, the National Front has established itself as one of the main political parties in France and also as the strongest and most successful populist party of Europe as of 2015.[62]

Le Pen finished second in the 2017 election and lost in the second round of voting versus Emmanuel Macron which was held on 7 May 2017.

Hungary

The Hungarian parliamentary election, 2018 result was a victory for the Fidesz–KDNP alliance, preserving its two-thirds majority, with Viktor Orbán remaining Prime Minister. Orbán and Fidesz campaigned primarily on the issues of immigration and foreign meddling, and the election was seen as a victory for right-wing populism in Europe.

Germany

Since 2013, the most popular right-wing populist party in Germany has been Alternative for Germany which managed to finish third in the 2017 German federal election, making it the first right-wing populist party to enter the Bundestag, Germany's national parliament. Before, right-wing populist parties had gained seats in German State Parliaments only. Left-wing populism is represented in the Bundestag by The Left party.

On a regional level, right-wing populist movements like Pro NRW and Citizens in Rage (Bürger in Wut, BIW) sporadically attract some support. In 1989, The Republicans (Die Republikaner) led by Franz Schönhuber entered the Abgeordnetenhaus of Berlin and achieved more than 7% of the German votes cast in the 1989 European election, with six seats in the European Parliament. The party also won seats in the Landtag of Baden-Württemberg twice in 1992 and 1996, but after 2000 the Republicans' support eroded in favour of the far-right German People's Union and the Neo-Nazi National Democratic Party of Germany (NPD), which in the 2009 federal election held 1.5% of the popular vote (winning up to 9% in regional Landtag parliamentary elections).

In 2005, a nationwide Pro Germany Citizens' Movement (pro Deutschland) was founded in Cologne. The Pro Germany movement appears as a conglomerate of numerous small parties, voters' associations and societies, distinguishing themselves by campaigns against Islamic extremism[63] and Muslim immigrants. Its representatives claim a zero tolerance policy and the combat of corruption. With the denial of a multiethnic society (Überfremdung) and the islamization, their politics extend to far-right positions. Other minor right-wing populist parties include the German Freedom Party founded in 2010, the former East German German Social Union (DSU) and the dissolved Party for a Rule of Law Offensive ("Schill party").

Greece

The most prominent right-wing populist party in Greece is the Independent Greeks (ANEL).[64][65] Despite being smaller than the more extreme Golden Dawn party, after the January 2015 legislative elections ANEL formed a governing coalition with the left-wing Coalition of the Radical Left (SYRIZA), thus making the party a governing party and giving it a place in the Cabinet of Alexis Tsipras.[66]

The Golden Dawn has grown significantly in Greece during the country's economic downturn, gaining 7% of the vote and 18 out of 300 seats in the Hellenic Parliament. The party's ideology includes annexation of territory in Albania and Turkey, including the Turkish cities of Istanbul and Izmir.[67] Controversial measures by the party included a poor people's kitchen in Athens which only supplied to Greek citizens and was shut down by the police.[68]

The Popular Orthodox Rally is not represented in the Greek legislature, but supplied 2 of the country's 22 MEPS until 2014. It supports anti-globalisation and lower taxes for small businesses as well as opposition to Turkish accession to the European Union and the Republic of Macedonia's use of the name Macedonia as well as immigration only for Europeans.[69] Its participation in government has been one of the reasons why it became unpopular with its voters who turned to Golden Dawn in Greece's 2012 elections.[70]

Italy

.jpg)

In Italy, the most prominent right-wing populist party is Lega Nord (LN),[71] whose leaders reject the right-wing label,[72][73][74] though not the "populist" one.[75] LN is a federalist, regionalist and sometimes secessionist party, founded in 1991 as a federation of several regional parties of Northern and Central Italy, most of which had arisen and expanded during the 1980s. LN's program advocates the transformation of Italy into a federal state, fiscal federalism and greater regional autonomy, especially for the Northern regions. At times, the party has advocated for the secession of the North, which it calls Padania. The party generally takes an anti-Southern Italian stance as members are known for opposing Southern Italian emigration to Northern Italian cities, stereotyping Southern Italians as welfare abusers and detrimental to Italian society and attributing Italy's economic troubles and the disparity of the North-South divide in the Italian economy to supposed inherent negative characteristics of the Southern Italians, such as laziness, lack of education or criminality.[76][77][78][79] Certain LN members have been known to publicly deploy the offensive slur "terrone", a common pejorative term for Southern Italians that is evocative of negative Southern Italian stereotypes.[76][77][80] As a federalist, regionalist, populist party of the North, LN is also highly critical of the centralized power and political importance of Rome, sometimes adopting to a lesser extent an anti-Roman stance in addition to an anti-Southern stance.

With the rise of immigration into Italy since the late 1990s, LN has increasingly turned its attention to criticizing mass immigration to Italy. The LN, which also opposes illegal immigration, is critical of Islam and proposes Italy's exit from the Eurozone, is considered a Eurosceptic movement and as such it joined the Europe of Freedom and Democracy (EFD) group in the European Parliament after the 2009 European Parliament election. LN was or is part of the national government in 1994, 2001–2006, 2008–2011 and 2018-present. Most recently, the party, which notably includes among its members the Presidents of Lombardy and Veneto, won 17.4% of the vote in the 2018 general election, becoming the third-largest party in Italy (largest within the centre-right coalition). In the 2014 European election, under the leadership of Matteo Salvini it took 6.2% of votes. Under Salvini, the party has to some extent embraced Italian nationalism and emphasised Euroscepticism, opposition to immigration and other "populist" policies, while forming an alliance with right-wing populist parties in Europe.[81][82][83]

Silvio Berlusconi, leader of Forza Italia and Prime Minister of Italy from 1994–1995, 2001–2006 and 2008–2011, has sometimes been described as a right-wing populist, although his party is not typically described as such.[84][85]

A number of national conservative, nationalist and arguably right-wing populist parties are strong especially in Lazio, the region around Rome and Southern Italy. Most of them are heirs of the Italian Social Movement (a neo-fascist party, whose best result was 8.7% of the vote in the 1972 general election) and its successor National Alliance (which reached 15.7% of the vote in 1996 general election). They include the Brothers of Italy (2.0% in 2013), The Right (0.6%), New Force (0.3%), CasaPound (0.1%), Tricolour Flame (0.1%), Social Idea Movement (0.01%) and Progetto Nazionale (0.01%).

Additionally, in the German-speaking South Tyrol the local second-largest party, Die Freiheitlichen, is often described as a right-wing populist party.

Netherlands

In the Netherlands, right-wing populism was represented in the 150-seat House of Representatives in 1982, when the Centre Party won a single seat. During the 1990s, a splinter party, the Centre Democrats, was slightly more successful, although its significance was still marginal. Not before 2002 did a right-wing populist party break through in the Netherlands, when the Pim Fortuyn List won 26 seats and subsequently formed a coalition with the Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA) and People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD). Fortuyn, who had strong views against immigration, particularly by Muslims, was assassinated in May 2002, two weeks before the election.[86] The coalition had broken up by 2003, and the party went into steep decline until it was dissolved.

Since 2006, the Party for Freedom (PVV) has been represented in the House of Representatives. Following the 2010 general election, it has been in a pact with the right-wing minority government of CDA and VVD after it won 24 seats in the House of Representatives. The party is Eurosceptic and plays a leading role in the changing stance of the Dutch government towards European integration as they came second in the 2009 European Parliament election, winning 4 out of 25 seats. The party's main programme revolves around strong criticism of Islam, restrictions on migration from new European Union countries and Islamic countries, pushing for cultural assimilation of migrants into Dutch society, opposing the accession of Turkey to the European Union, advocating for the Netherlands to withdraw from the European Union and advocating for a return to the guilder through ending Dutch usage of the euro.[87]

The PVV withdrew its support for the First Rutte cabinet in 2012 after refusing to support austerity measures. This triggered the 2012 general election in which the PVV was reduced to 15 seats and excluded from the new government.

In the Dutch general election, 2017, Wilders' PVV gained an extra five seats to become the second largest party in the Dutch House of Representatives, bringing their total to 20 seats.[88]

From 2017 onwards, the Forum for Democracy has emerged as another right-wing populist force in the Netherlands.[89][90]

Poland

The largest right-wing populist party in Poland is Law and Justice, which currently holds both the presidency and a governing majority in the Sejm. It combines social conservatism and criticism of immigration with strong support for NATO and an interventionist economic policy.[91]

Polish Congress of the New Right, headed by Michał Marusik, aggressively promotes fiscally conservative concepts like radical tax reductions preceded by abolishment of social security, universal public healthcare, state-sponsored education and abolishment of Communist Polish 1944 agricultural reform as a way to dynamical economic and welfare growth.[92][93] Due to lack of empirical and economic evidences presented by party leaders and members, the party is considered populist both by right-wing and left-wing publicists[94][95]

Sweden

The Sweden Democrats are the third largest party in Sweden with 12,9 % of popular votes in the parlamentary election of 2014.

Switzerland

In Switzerland, the right-wing populist Swiss People's Party (SVP) reached an all-time high in the 2015 elections. The party is mainly considered to be national conservative,[96][97] but it has also variously been identified as "extreme right"[98] and "radical right-wing populist",[99] reflecting a spectrum of ideologies present among its members. In its far-right wing, it includes members such as Ulrich Schlüer, Pascal Junod, who heads a New Right study group and has been linked to Holocaust denial and neo-Nazism.[100][101]

In Switzerland, radical right populist parties held close to 10% of the popular vote in 1971, were reduced to below 2% by 1979 and again grew to more than 10% in 1991. Since 1991, these parties (the Swiss Democrats and the Swiss Freedom Party) have been absorbed by the SVP. During the 1990s, the SVP grew from being the fourth largest party to being the largest and gained a second seat the Swiss Federal Council in 2003, with prominent politician and businessman Christoph Blocher. In 2015, the SVP received 29.4% of the vote, the highest vote ever recorded for a single party throughout Swiss parliamentary history.[102][103][104][105]

United Kingdom

Media outlets such as The New York Times have called the UK Independence Party (UKIP), led by Nigel Farage, the largest right-wing populist party in the United Kingdom.[106] UKIP campaigned for an exit from the European Union prior to the 2016 European membership referendum[107] and a points-based immigration system similar to that used in Australia.[108][109][110]

The United Kingdom's governing Conservative Party has seen defections to UKIP over the European Union and immigration debates as well as LGBT rights.[111]

In the Conservative Party, former Mayor of London and Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson has been described as expressing right-wing populist views during the successful Vote Leave campaign.[112] Jacob Rees-Mogg, another potential party leadership contender, has been described as a right-wing populist.[113]

In Northern Ireland, the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) is the main right-wing populist force.[114]

United States

Moore (1996) argues that "populist opposition to the growing power of political, economic, and cultural elites" helped shape "conservative and right-wing movements" since the 1920s.[115] Historical right-wing populist figures in both major parties in the United States have included Thomas E. Watson, Strom Thurmond, Joe McCarthy, Barry Goldwater, George Wallace and Pat Buchanan.[116] When Conservative Democrats dominated the politics in the Democratic Party, populism was a faction in the Democrats, while the Republicans adopt some forms of populism since 1980s.

The Tea Party movement has been characterized as "a right-wing anti-systemic populist movement" by Rasmussen and Schoen (2010). They add: "Today our country is in the midst of a...new populist revolt that has emerged overwhelmingly from the right – manifesting itself as the Tea Party movement".[117] In 2010, David Barstow wrote in The New York Times: "The Tea Party movement has become a platform for conservative populist discontent".[118] Some political figures closely associated with the Tea Party, such as U.S. Senator Ted Cruz and former U.S. Representative Ron Paul, have been described as appealing to right-wing populism.[119][120][121] In the U.S. House of Representatives, the Freedom Caucus, which is associated with the Tea Party movement, has been described as right-wing populist.[122]

Donald Trump's 2016 presidential campaign, noted for its anti-establishment and anti-immigration rhetoric, was characterized as that of a right-wing populist.[123][124] The ideology of Trump’s former Chief Strategist, Steve Bannon, has also been described as such.[125]

Right-wing populist political parties

Current right-wing populist parties or parties with right-wing populist factions

Represented in national legislatures

.svg.png)

Not represented in national legislatures

.svg.png)

Former right-wing populist parties or parties with right-wing populist factions

.svg.png)

See also

- Alt-right

- Anti-establishment

- Brexit

- Christian right

- Dark Enlightenment

- Economic nationalism

- Euroscepticism

- Hindutva

- Left-wing populism

- National conservatism

- National liberalism

- New nationalism (21st century)

- Opposition to immigration

- Outline of right-wing populism

- Paleoconservatism

- Paternalistic conservatism

- Radical right

- Reactionary

- Revisionist Zionism

- Right-wing authoritarianism

- Social conservatism

- Traditional conservatism

- Ultranationalism

Notes

- ↑ Sharpe, Matthew. "The metapolitical long game of the European New Right". The Conversation. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ Traub, James. "The Geert Wilders Effect and the national election in the Netherlands". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ Buruma, Ian (10 March 2017). "How the Dutch Stopped Being Decent and Dull". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ "The New Nationalism". Online Library of Law & Liberty. 8 December 2016. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ Taub, Amanda (8 July 2016). "A Central Conflict of 21st-Century Politics: Who Belongs?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ North, Bonnie. "The Rise of Right-Wing Nationalist Political Parties in Europe". Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ "Fear of Diversity Made People More Likely to Vote Trump". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ "The political lexicon of a billionaire populist". Washington Post. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ "The End of Reaganism". POLITICO Magazine. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ Greven, Thomas (May 2016). "The Rise of Right-wing Populism in Europe and the United States" (PDF). Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

- ↑ Bangstad, Sindre (2018). "The New Nationalism and its Relationship to Islam". Diversity and Contestations over Nationalism in Europe and Canada. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 285–311. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-58987-3_11. ISBN 978-1-137-58986-6.

- ↑ Edsall, Thomas (16 December 2014). "The Rise of 'Welfare Chauvinism'". New York Times. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ Rippon, Haydn (4 May 2012). "The European far right: actually right? Or left? Or something altogether different?". The Conversation. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ Matlack, Carol (20 November 2013). "The Far-Left Economics of France's Far Right". Business Week. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ Norris 2005, p. 3.

- ↑ Kaplan & Weinberg 1998, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ "The Trump phenomenon and the European populist radical right". Washington Post. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ Kaplan & Weinberg 1998, pp. 10–13.

- ↑ Judis, John B. (5 October 2016). The Populist Explosion: How the Great Recession Transformed American and European Politics. Columbia Global Reports. ISBN 978-0997126440.

- ↑ Cooper, Ryan (15 March 2017). "The Great Recession clearly gave rise to right-wing populism". The Week. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ↑ Sarmadi, Dario (20 October 2015). "Far-right parties always gain support after financial crises, report finds". EURACTIV. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ↑ "The map which shows how Ukip support is growing in every constituency but two". The Independent. 15 May 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ Hunt, Alex (21 November 2014). "UKIP: The story of the UK Independence Party's rise". BBC News. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ Lowe, Josh; Matthews, Owen; AM, Matt McAllester On 11/23/16 at 9:02 (23 November 2016). "Why Europe's populist revolt is spreading". Newsweek. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ "Trump's 6 populist positions". POLITICO. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ Reinhard, Beth (8 November 2016). "Donald Trump Ends Election 2016 the Way He Started It". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ "How Donald Trump's nationalism won over white Americans". Newsweek. 15 November 2016. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ Norris 2005, pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Kaplan & Weinberg 1998, pp. 10–11.

- ↑ "From 'Brexit' To Trump, Nationalist Movements Gain Momentum Around World". NPR.org. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ Norris 2005, p. 44.

- ↑ Ignazi 2002, p. 26.

- ↑ Mudde, C. (2002). The Ideology of the Extreme Right. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719064463. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ Norris 2005, pp. 68–69, 72.

- ↑ "The rise of populist politics in Australia". BBC. 1 March 2017.

- ↑ "Pauline Hanson's One Nation emerges as government's most reliable Senate voting partner". Sydney Morning Herald. 4 March 2017.

- ↑ "Turnbull challenged by populist upstart". The Times. 7 February 2017.

- ↑ "Meet Bob and David, our new libertarian senators". Australian Financial Review. 12 July 2014.

- ↑ The mice that may yet roar: who are the minor right-wing parties?. The Conversation. 28 August 2013.

- ↑ "Bernardi's alliance intends to bloc Xenophon". The Australian. 27 April 2017.

- ↑ Mondon, Aurélien (2013). The Mainstreaming of the Extreme Right in France and Australia. Routledge.

If ... Abbott failed to satisfy the electorate he has assuaged with his right-wing populism, a return to more traditionally extreme politics could be a real possibility

- ↑ "Australia's Turnbull Digs In as Rival Dutton Seeks Leadership". Bloomberg. 22 August 2018.

- ↑ "'Irresponsible' populism: Lisa Raitt slams Kevin O'Leary, Kellie Leitch".

- ↑ "Could Trumpism Take Root in Canada?". Pacific Standard. 15 March 2017. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ "Patrick Brown returns to Queen's Park for budget speech". Toronto Star. 28 March 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Anti-elitist politicians in Canada are courting immigrants". The Economist. 19 April 2018.

- 1 2 "Maxime Bernier Launches 'The People's Party of Canada'". Complex. 14 September 2018.

- ↑ "EU leaders to hold talks on Russian political meddling". Financial Times. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ↑ "Czech Republic accuses Putin of backing EU's rightwing". Financial Times. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ↑ "Elections 2004 – Flemish Council – List Results". polling2004.belgium.be. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ "Court rules Vlaams Blok is racist". BBC News. 9 November 2004.

- ↑ Vlaams Belang (7 January 2005). "Programmaboek 2004" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ " Advertisement". haaretz.com. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ "Vlaams Parlement". vlaamsparlement.be. Archived from the original on 7 January 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑

- ↑ Jens Rydgren. "Explaining the Emergence of Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties: The Case of Denmark" West European Politics, Vol. 27, No. 3, May 2004, pp. 474–502."

- ↑ Givens, Terri E. (2005). Voting radical right in Western Europe. Cambridge University. pp. 136–39. ISBN 978-0-521-85134-3.

- ↑ "Head of Danish Populist Party to Resign". Associated Press. 8 August 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ↑ Eddy, Melissa (18 June 2015). "Anti-Immigrant Party Gains in Denmark Elections". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ "The Party Program of the Danish People's Party". danskfolkeparti. October 2002. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013.

- ↑ "Her er Danmarks nye borgerlige parti: Vil udfordre DF og LA" (in Danish). TV 2 News. 20 October 2015. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ↑ "'A grave moment for France': National Front sweeps to victory in Paris leaving Socialist government fighting for life – and in Germany a neo-Nazi is elected for first time in decades". 25 May 2014.

- ↑ "Salafists and Right-Wing Populists Battle in Bonn". Spiegel. 5 July 2012.

- 1 2 Boyka M. Stefanova (14 November 2014). The European Union beyond the Crisis: Evolving Governance, Contested Policies, and Disenchanted Publics. Lexington Books. p. 261. ISBN 978-1-4985-0348-8.

- ↑ Christian Karner; Bram Mertens (30 September 2013). The Use and Abuse of Memory: Interpreting World War II in Contemporary European Politics. Transaction Publishers. p. 168. ISBN 978-1-4128-5203-6.

- ↑ "Greece anti-bailout leader Tsipras made prime minister". BBC News.

- ↑ "Greek far-right leader vows to 'take back' İstanbul, İzmir". todayszaman.com. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ Squires, Nick (2 May 2013). "Golden Dawn's 'Greeks only' soup kitchen ends in chaos". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ↑ "Tribunes and Patricians: Radical Fringe Parties in the 21st Century" (PDF). carleton.ca. 16 January 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ "Continent of Fear: The Rise of Europe's Right-Wing Populists". spiegel.de. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ "Così la Lega conquista nuovi elettori (non solo al nord)". ilfoglio.it. Archived from the original on 21 May 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ "Lega Nord: Maroni ne' destra ne' sinistra, alleanze dopo congresso". asca.it. Archived from the original on 21 May 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ "INTERVISTA Matteo Salvini (Lega): "Renzi? Peggio di Monti, vergognoso con la Merkel". termometropolitico.it. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ "Lega Nord". leganord.org. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- 1 2 Tambini, Damian (6 December 2012). Nationalism in Italian Politics: The Stories of the Northern League, 1980–2000. Routledge.

- 1 2 Russo Bullaro, Grace (2010). From Terrone to Extracomunitario: New Manifestations of Racism in Contemporary Italian Cinema : Shifting Demographics and Changing Images in a Multi-cultural Globalized Society. Troubador Publishing Ltd. pp. 179–81.

- ↑ Willey, David (14 April 2012). "The rise and fall of Northern League founder Umberto Bossi". BBC News. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ↑ Pullella, Philip (8 March 2011). "Italy unity anniversary divides more than unites". Reuters. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ↑ Garau, Eva (17 December 2014). Politics of National Identity in Italy: Immigration and 'Italianità'. Routledge. pp. 110–11. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ↑ "Italy's Northern League Is Suddenly In Love With the South". 20 February 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2018 – via www.bloomberg.com.

- ↑ "Rivoluzione nella Lega: cambiano nome e simbolo". 24 July 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ↑ "Lega, nuovo simbolo senza "nord". Salvini: "Sarà valido per tutta Italia"". 27 October 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ↑ Liang, Christina (2016), Europe for the Europeans: The Foreign and Security Policy of the Populist Radical Right, Routledge, p. 187

- ↑ Feffer, John (23 November 2016). "What Europe Can Teach Us about Trump". Foreign Policy in Focus.

- ↑ "In pictures: Death of Pim Fortuyn". BBC News. 7 May 2002.

- ↑ "Far-right outcast Geert Wilders vows to 'de-Islamise' the Netherlands after taking lead in Dutch polls". The Independent. 12 February 2017. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ CNN, Lauren Said-Moorhouse and Bryony Jones. "Dutch elections: Wilders' far-right party beaten, early results show". CNN. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ "The Dutch defeat 'the wrong kind of populism'". Heinrich Böll Foundation. 22 March 2017.

- ↑ "Is Dutch Bad Boy Thierry Baudet the New Face of the European Alt-Right?".

- ↑ "In Poland, a right-wing, populist, anti-immigrant government sees an ally in Trump". LA Times. 5 July 2017. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ↑ "Korwin-Mikke: Feudalizmie wróć! | Najwyższy Czas!". nczas.com. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ "Program KNP". nowaprawicajkm.pl. Archived from the original on 7 January 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ "Korwin-Mikke – guru nonsensu Gazeta wSieci". wsieci.pl. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ "Wirus korwinizmu – Krzysztof Derebecki – Mój lewicowy punkt widzenia". lewica.pl. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ Skenderovic 2009, p. 124: "... and prefers to use terms such as 'national-conservative' or 'conservative-right' in defining the SVP. In particular, 'national-conservative' has gained prominence among the definitions used in Swiss research on the SVP".

- ↑ Geden 2006, p. 95.

- ↑ Ignazi 2006, p. 234.

- ↑ H-G Betz, 'Xenophobia, Identity Politics and Exclusionary Populism in Western Europe', L. Panitch & C. Leys (eds.), Socialist Register 2003 – Fighting Identities: Race, Religion and Ethno-nationalism, London: Merlin Press, 2002, p. 198

- ↑ "Antisemitism And Racism in Switzerland 2000-1". Archived from the original on 21 April 2002. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ "Antisemitism and Racism in Switzerland 1999–2000". tau.ac.il. Archived from the original on 25 October 2007. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ↑ "Anti-immigration party wins Swiss election in 'slide to the Right'". The Daily Telegraph. Reuters. 19 October 2015. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ "Anti-immigration SVP wins Swiss election in big swing to right". BBC News. 19 October 2015. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ Larson, Nina (19 October 2015). "Swiss parliament shifts to right in vote dominated by migrant fears". Yahoo!. AFP. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ "Amid rising fears over refugees, far-right party gains ground in Swiss election". Deutsche Welle. 19 October 2015. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ Ashkenas, Jeremy; Aisch, Gregor (5 December 2016). "European Populism in the Age of Donald Trump". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ "Who wants to leave the European Union?". The Telegraph. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ Goodwin & Milazzo 2015, pp. 172, 231; Heywood 2015, p. 139.

- ↑ Merrick, Jane; Rentoul, John (19 January 2014). "Ukip tops Independent on Sunday poll as the nation's favourite party". The Independent. London.

- ↑ "Poll says Labour still on course for 2015 victory – but UKIP is now Britain's 'favourite' political party". mirror.co.uk. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ Ross, Tim (19 May 2013). "Tories begin defecting to Ukip over 'loons' slur". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ↑ Levitz, Eric (30 June 2016). "Boris Johnson Brexit But Won't Buy it". New York Magazine.

- ↑ "Populism's Latest Twist: An Aristocrat Could Be Britain's Prime Minister". New York Observer. 14 July 2017.

- 1 2 Ingle, Stephen (2008). The British Party System: An Introduction. Routledge. p. 156.

- ↑ Leonard J. Moore, "Good Old-Fashioned New Social History and the Twentieth-Century American Right," Reviews in American History vol 24#4 (1996) pp. 555–73, quote at p. 561

- ↑ Stark, Steven (February 1996). "Right-Wing Populist". The Atlantic.

- ↑ Scott Rasmussen and Doug Schoen, Mad As Hell: How the Tea Party Movement Is Fundamentally Remaking Our Two-Party System (2010) quotes on p. 19

- ↑ David Barstow, "Tea Party Lights Fuse for Rebellion on Right," New York Times Feb 6, 2010

- ↑ "What On Earth Is Ted Cruz Doing?". Vanity Fair. 23 September 2016.

- ↑ "Playing with fear". The Economist. 12 December 2015.

- ↑ Maltsev, Yuri (2013). The Tea Party Explained: From Crisis to Crusade. Open Court. p. 26.

- ↑ "In The Freedom Caucus, Trump Meets His Match". The Atlantic. 7 April 2017.

- ↑ Dolgert 2016; Greven 2016.

- ↑ Neiwert, David (2016). "Trump and Right-Wing Populism: A Long Time Coming" (PDF). The Public Eye. No. 86. Somerville, Massachusetts: Political Research Associates. pp. 3, 19. ISSN 0275-9322. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ↑ "The future of Bannonism".

- ↑ Mondon, Aurelien (2016). The Mainstreaming of the Extreme Right in France and Australia. Routledge.

- 1 2 "The mice that may yet roar: who are the minor right-wing parties?". The Conversation. 28 August 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Hans-Jürgen Bieling (2015). "Uneven development and 'European crisis constitutionalism', or the reasons for and conditions of a 'passive revolution in trouble'". In Johannes Jäger; Elisabeth Springler. Asymmetric Crisis in Europe and Possible Futures: Critical Political Economy and Post-Keynesian Perspectives. Routledge. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-317-65298-4.

- 1 2 Eric Micklin (2015). "The Austrian Parliament and EU Affairs: Gradually Living Up to its Legal Potential". In Claudia Hefftler; Christine Neuhold; Olivier Rosenberg; et al. The Palgrave Handbook of National Parliaments and the European Union. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 389. ISBN 978-1-137-28913-1.

- 1 2 3 Peter Starke; Alexandra Kaasch; Franca Van Hooren (2013). The Welfare State as Crisis Manager: Explaining the Diversity of Policy Responses to Economic Crisis. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 193. ISBN 978-1-137-31484-0.

- ↑ Pauwels, Teun (2013). Belgium: Decline of National Populism?. Exposing the Demagogues: Right-wing and National Populist Parties in Europe. Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, CES. p. 85.

- ↑ "Poslanici". Parliamentary Assembly of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ↑ Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia, Dimitar Bechev, Scarecrow Press, 2009, ISBN 0810862956, p. 104.

- ↑ Smilova, Ruzha; Smilov, Daniel; Ganev, Georgi (2012). Democracy and the Media in Bulgaria: Who Represents the People?. Understanding Media Policies: A European Perspective. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 48–49.

- ↑ "How Kellie Leitch touched off a culture war - Macleans.ca". macleans.ca. 23 September 2016. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ↑ "Groundswell of right-wing populism will test our Canadian resolve, readers say".

- ↑ "The popular comeback of populist politics".

- ↑ "Kellie Leitch latches on to Trump victory".

- ↑ "The Conservative Party Of Canada Is Ripe For A Populist Takeover - Kellie Leitch stands out in a crowd of conventional conservatives".

- ↑ "After Loss in Austria, a Look at Europe's Right-wing Parties". Haaretz. 24 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Pausch, Robert (4 February 2015). "Populismus oder Extremismus? – Radikale Parteien in Europa". Retrieved 28 April 2017 – via Die Zeit.

- 1 2 Daniele Caramani; Yves Mény (2005). Challenges to Consensual Politics: Democracy, Identity, and Populist Protest in the Alpine Region. Peter Lang. p. 151. ISBN 978-90-5201-250-6.

- ↑ "Contentious politics in the Baltics: the 'new' wave of right-wing populism in Estonia". openDemocracy. 28 April 2016.

- ↑ Ivaldi, Gilles (2018). "Crowding the market: the dynamics of populist and mainstream competition in the 2017 French presidential elections". p. 6.

- ↑ Antonis Galanopoulos: Greek right-wing populist parties and Euroscepticism(PDF), p.2 "Golden Dawn is also Eurosceptical and it is opposing Greece's participation in the European Union and the Eurozone"

- ↑ Betz, Hans-Georg (1994). Radical Right-Wing Populism in Western Europe (The New Politics of Resentment). Palgrave MacMillan. p. 4. ISBN 0-312-08390-4.

the majority of radical right-wing populist parties are radical in their rejection of the established socio-cultural and socio-political system

- ↑ Wodak, Ruth (2013). Right-Wing Populism in Europe: Politics and Discourse. A&C Black. p. 23.

- ↑ Prakash, Gyan (2010). Mumbai Fables. Princeton University Press. p. 9.

- ↑ Carlo Ruzza; Stefano Fella (2009). Re-inventing the Italian Right: Territorial Politics, Populism and 'post-fascism'. Routledge. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-1-134-28634-8.

- ↑ Liang, Kristina (2016). Europe for the Europeans: The Foreign and Security Policy of the Populist Radical Right. Routledge. p. 187.

- 1 2 "Right-wing Populism Wins in Britain and Israel". Haaretz. 3 July 2016.

- ↑ Ganesan (2015). Bilateral Legacies in East and Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 67.

- ↑ Auers; Kasekamp, Comparing Radical-Right Populism in Estonia and Latvia, pp. 235–236

- ↑ "Liechtenstein Populist Party Gains Ground in Parliamentary Elections". Deutsche Welle. 5 February 2017. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ↑ Stefanini, Sara (5 February 2017). "Liechtenstein's Populists Gain Ground". Politico. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ↑ Balcere, Ilze (2011), Comparing Populist Political Parties in the Baltic States and Western Europe (PDF), European Consortium for Political Research, pp. 5–6

- ↑ Verlag, Bielefeld (2014). "Doing Identity in Luxembourg". Transaction Publishers: 55.

- ↑ "The Dutch defeat 'the wrong kind of populism'". Heinrich Böll Foundation. 22 March 2017.

- ↑ Wolfram Nordsieck (2013). "Parties and Elections in Europe: Norway". www.parties-and-elections.eu. Parties and Elections in Europe.

- 1 2 "Rechtspopulistische und rechtsextreme Parteien in Europa". Federal Agency for Civic Education. December 2016.

- ↑ Wolfram Nordsieck. "Parties and Elections in Europe". Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ "Wolfram Nordsieck, Parties and Elections in Europe". Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ↑ Wodak, Ruth; Mral, Brigitte (2013). Right-Wing Populism in Europe: Politics and Discourse. A&C Black. p. 19.

- ↑ "Populism in the Balkans. The Case of Serbia" (PDF). Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ↑ "After Austria election, a look at Europe right wing parties". Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ↑ "Serbian political outline". Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ↑ Wolfram Nordsieck. "Parties and elections". Parties-and-elections.de. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ↑ Alica Rétiová. "A Hero Is Coming! The master narrative of Marián Kotleba in the Slovak regional election of 2013". Masaryk University. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ↑ "A right-wing extremist or people's protector? Media coverage of extreme right leader Marian Kotleba in 2013 regional elections in Slovakia | Kluknavská | Intersections. East European Journal of Society and Politics". Intersections.tk.mta.hu. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ↑ "Slowakei: Rechte wollen Fico verhindern". Der Standard (in German). Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ↑ Jang Hoon. "Liberty Korea Party, conservative populism has no future". JoongAng Ilbo. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ↑ Mazzoleni, Oskar (2007), "The Swiss People's Party and the Foreign and Security Policy Since the 1990s", Europe for the Europeans: The Foreign and Security Policy of the Populist Radical Right, Ashgate, p. 223

- ↑ "Les populistes brillent aux élections genevoises" (in French). Swissinfo. 11 October 2009. Archived from the original on 26 September 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- ↑ "Cross-Border Issues Cloud Geneva Election Result". Swissinfo. 11 November 2013. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ↑ "Nationales Forschungsprogramm 40+".

- ↑ Gunes, Cengiz (2013). "The Kurdish Question in Turkey". Routledge: 270.

- ↑ Abadan-Unat, Nermin (2011). Turks in Europe: From Guest Worker to Transnational Citizen. New York: Berghahn Books. p. 19. ISBN 9781845454258.

...the fascist Nationalist Movement Party...

- ↑ "Erdogans Widersacher".

- ↑ "Erdogan überrumpelt die Türkei".

- ↑ Kuzio, Taras (November–December 2010), "Populism in Ukraine in a Comparative European Context" (PDF), Problems of Post-Communism, M.E. Sharpe, 57 (6): 6, 15, doi:10.2753/ppc1075-8216570601, retrieved 16 October 2012,

Anti-Semitism only permeates Ukraine’s far-right parties, such as Svoboda… Ukraine’s economic nationalists are to be found in the extreme right (Svoboda) and centrist parties that propagate economic nationalism and economic protectionism.

- ↑ Ivaldi, Gilles (2011), "The Populist Radical Right in European Elections 1979-2009", The Extreme Right in Europe, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, p. 20

- ↑ "Lords by party, type of peerage and gender". Parliament of the United Kingdom. 8 March 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ↑ Panitch, Leo (2015). The Politics of the Right. NYU Press. p. ix.

- ↑ Cassidy, John (29 February 2016). "Donald Trump is Transforming the G.O.P. Into a Populist, Nativist Party". The New Yorker.

- ↑ Gould, J.J. (2 July 2016). "Why Is Populism Winning on the American Right?". The Atlantic.

- ↑ "Der Rückfall ins Nationale". Deutsche Welle. 2011.

- ↑ Cas Mudde; Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser (2012). Populism in Europe and the Americas: Threat Or Corrective for Democracy?. Cambridge University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-107-02385-7. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ↑ "European Election Database (EED)". uib.no. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ↑ "Rechtspopulistische Parteien in Tschechien. - Vile Netzwerk". vile-netzwerk.de. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ↑ Paul Hainsworth (2008). The Extreme Right in Western Europe. Routledge. p. 49

- ↑ Christina Schori Liang (2013). "'Nationalism Ensures Peaces': the Foreign and Security Policy of the German Populist Radical Right After Reunification". In Christina Schori Liang. Europe for the Europeans: The Foreign and Security Policy of the Populist Radical Right. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-4094-9825-4.

- ↑ Lokaler Aktionsplan für Demokratie, Toleranz und für ein weltoffenes Chemnitz (LAP). Archived 8 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine. (PDF; 275 kB) Fortschreibung 2012. Stand: November 2011, veröffentlicht auf chemnitz.de

- ↑ Swen Uhlig: NPD plant Aufmarsch in Chemnitz, freiepresse.de, 16. Februar 2010.

- ↑ "Pro Köln unterliegt vor Gericht", FOCUS, 10 July 2009, retrieved 19 October 2011

- ↑ "Pro Deutschland protestiert vor Norwegen-Botschaft", Berliner Morgenpost, 25 July 2011, retrieved 19 October 2011

- ↑ Alexander Häusler (Hrsg.): Rechtspopulismus als „Bürgerbewegung“. Kampagnen gegen Islam und Moscheebau und kommunale Gegenstrategien. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-531-15919-5.

- ↑ Kristian Frigelj: Rechtspopulisten planen Anti-Minarett-Kampagne. In: Die Welt, 14. Dezember 2009.

- ↑ "Obdachlose Rechtspopulisten", Süddeutsche Zeitung, retrieved 30 August 2011

- ↑ Gemenis, Kostas (2008) "The 2007 Parliamentary Election in Greece", Mediterranean Politics 13: 95–101 and Gemenis, Kostas and Dinas, Elias (2009) "Confrontation still? Examining parties' policy positions in Greece", Comparative European Politics.

- ↑ Art, David (2011), Inside the Radical Right: The Development of Anti-Immigrant Parties in Western Europe, Cambridge University Press, p. 188

- ↑ Rita O'Reilly (24 October 2013). A Matter of Trust - RTÉ Prime Time (Investigative Documentary into the Freeman movement in Ireland, National Television). Dublin, Ireland: Radio Teilifís Éireann.

- ↑ "Radio: A thin turnout on air, but Pat Kenny may yet win the populist vote". The Irish Times. 5 October 2013. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- ↑ Mark Moloney (May 2013). "Ben Gilroy and Direct Democracy Ireland: Look behind them". An Phoblacht, Vol 36, Issue 4. p. 27.

- 1 2 Wolfram Nordsieck. "Parties and Elections in Europe: The database about parliamentary elections and political parties in Europe, by Wolfram Nordsieck". Parties-and-elections.eu. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ↑ "BürgerUnion bei Wahlauftakt der Tiroler FPÖ" (in German). Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ↑ "Herr Pöder, was tun Sie bei Pegida?" (in German), Salto.bz, 13 January 2015, https://www.salto.bz/de/article/13012015/herr-poeder-was-tun-sie-bei-pegida. Retrieved 27 January 2018

- ↑ "Nicht wählen ist keine Lösung." (in German), brennerbasisdemokratie.eu, 25 February 2018, http://www.brennerbasisdemokratie.eu/?p=39253. Retrieved 27 January 2018

- ↑ Berend, Iván T. (2010), Europe Since 1980, Cambridge University Press, p. 134

- ↑ Anglada: "Being populist and identitarian is being honestly democratic" Archived 3 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Minuto Digital (Spanish)

- ↑ Golder, M. (2003). "Explaining Variation in the Success of Extreme Right Parties in Western Europe". Comparative Political Studies. 36 (4): 432. doi:10.1177/0010414003251176.

- ↑ Evans, Jocelyn A.J. (April 2005). "The dynamics of social change in radical right-wing populist party support". Comparative European Politics. Palgrave Macmillan. 3 (1): 76–101. doi:10.1057/palgrave.cep.6110050.

- ↑ Theodore R. Marmor; Richard Freeman; Kieke G. H. Okma (2009). Comparative Studies and the Politics of Modern Medical Care. Yale University Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-300-15595-2.

- ↑ Amir Abedi (2004). Anti-Political Establishment Parties: A Comparative Analysis. Routledge. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-134-36369-8.

- ↑ Carol Gould; Pasquale Paquino (2001). Cultural Identity and the Nation-state. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-8476-9677-2.

- ↑ Ian Budge; David Robertson; Derek Hearl (1987). Ideology, Strategy and Party Change: Spatial Analyses of Post-War Election Programmes in 19 Democracies. Cambridge University Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-521-30648-5.

- ↑ Nathalie Tocci (2007). Greece, Turkey and Cyprus. European Politics. Oxford University Press. p. 125.

- ↑ Stefan Engert (2010). EU Enlargement and Socialization: Turkey and Cyprus. Routledge. p. 146.

- ↑ Klausmann, Alexandra (21 May 2010). "Tschechien: Jugend vereint gegen Linksparteien". Wiener Zeitung (in German). Archived from the original on 6 June 2011.

- ↑ "Czech elections: An angry electorate", The Economist, 25 October 2013

- ↑ Paul Hainsworth (2008). The Extreme Right in Europe. Routledge. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-134-15432-6.

- 1 2 Christina Bergqvist, ed. (1999). Equal Democracies?: Gender and Politics in the Nordic Countries. Nordic Council of Ministers. p. 320. ISBN 978-82-00-12799-4.

- ↑ De Lange, Sarah L. (2008), Radical Right-wing Populist Parties in Government: determinants of coalition membership (PDF), p. 9

- 1 2 David Art (2011). "Memory Politics in Western Europe". In Uwe Backes; Patrick Moreau. The Extreme Right in Europe: Current Trends and Perspectives. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 361. ISBN 978-3-647-36922-8.

- ↑ Andeweg, R. and G. Irwin Politics and Governance in the Netherlands, Basingstoke (Palgrave) p.49

References

- Berlet, Chip and Matthew N. Lyons. 2000. Right-Wing Populism in America: Too Close for Comfort. New York: Guilford Press. ISBN 1-57230-568-1, ISBN 1-57230-562-2.

- Betz, Hans-Georg. Radical right-wing populism in Western Europe. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1994 ISBN 0-312-08390-4.

- Betz, Hans-Georg and Immerfall, Stefan. The New Politics of the Right: Neo-Populist Parties and Movements in Established Democracies. Houndsmill, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK, Macmillan Press Ltd., 1998 ISBN 978-0-312-21338-1,

- Dolgert, Stefan (2016). "The Praise of Ressentiment: Or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Donald Trump". New Political Science. 38 (3): 354–370. doi:10.1080/07393148.2016.1189030.

- Fielitz, Maik; Laloire, Laura Lotte (eds.) (2016). Trouble on the Far Right. Contemporary Right-Wing Strategies and Practices in Europe. Bielefeld: transcript. ISBN 978-3-8376-3720-5.

- Fritzsche, Peter. 1990. Rehearsals for Fascism: Populism and Political Mobilization in Weimar Germany. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505780-5.

- Geden, Oliver (2006). Diskursstrategien im Rechtspopulismus: Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs und Schweizerische Volkspartei zwischen Opposition und Regierungsbeteiligung [Discourse Strategies in Right-Wing Populism: Freedom Party of Austria and Swiss People's Party between Opposition and Government Participation] (in German). Wiesbaden, Germany: VS Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-3-531-90430-6. ISBN 978-3-531-15127-4.

- Goodwin, Matthew; Milazzo, Caitlin (2015). UKIP: Inside the Campaign to Redraw the Map of British Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198736110.

- Greven, Thomas (2016). The Rise of Right-wing Populism in Europe and the United States: A Comparative Perspective (PDF). Berlin: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- Heywood, Andrew (2015). Essentials of UK Politics (3rd ed.). London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-53074-5.

- Ignazi, Piero (2002). "The Extreme Right: Defining the Object and Assessing the Causes". In Schain, Martin; Zolberg, Aristide R.; Hossay, Patrick. Shadows over Europe: The Development and Impact of the Extreme Right in Western Europe. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-29593-6.

- ——— (2006) [2003]. Extreme Right Parties in Western Europe. Comparative Politics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-929159-5.

- Kaplan, Jeffrey; Weinberg, Leonard (1998). The Emergence of a Euro-American Radical Right. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-2564-8.

- Norris, Pippa (2005). Radical Right: Voters and Parties in the Electoral Market. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84914-2.

- Skenderovic, Damir (2009). The Radical Right in Switzerland: Continuity and Change, 1945–2000. New York: Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-84545-580-4. JSTOR j.ctt9qcntn.

- Ware, Alan (1996). Political Parties and Party Systems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-878076-2.

Further reading

- Goldwag, Arthur. The New Hate: A History of Fear and Loathing on the Populist Right. Pantheon, February 2012, ISBN 978-0-307-37969-6.

- Wodak, Ruth. The politics of fear: What right-wing populist discourses mean. London: Sage, 2015. ISBN 9781446247006.

- Wodak, Ruth, Brigitte Mral and Majid Khosravinik, editors. Right wing populism in Europe: politics and discourse. London. Bloomsbury Academic. 2013. ISBN 9781780932453.

External links

- "Fact check: The rise of right-wing populism in Europe". Channel 4 News (UK). 28 September 2017.