Populism

In politics, populism refers to a range of approaches which emphasise the role of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against "the elite". There is no single definition of the term, which developed in the 19th century and has been used to mean various things since that time. Few politicians or political groups describe themselves as "populists", and in political discourse the term is often applied to others pejoratively. Within political science and other social sciences, various different definitions of populism have been used, although some scholars propose rejecting the term altogether.

A common framework for interpreting populism is known as the ideational approach: this defines populism as an ideology which presents "the people" as a morally good force against "the elite", who are perceived as corrupt and self-serving. Populists differ in how "the people" are defined, but it can be based along class, ethnic, or national lines. Populists typically present "the elite" as comprising the political, economic, cultural, and media establishment, all of which are depicted as a homogenous entity and accused of placing the interests of other groups—such as foreign countries or immigrants—above the interests of "the people". According to this approach, populism is a thin-ideology which is combined with other, more substantial thick ideologies such as nationalism, liberalism, or socialism. Thus, populists can be found at different locations along the left–right political spectrum and there is both left-wing populism and right-wing populism.

Other scholars active in the social sciences have defined the term populism in different ways. According to the popular agency definition used by some historians of United States history, populism refers to popular engagement of the population in political decision making. An approach associated with the scholar Ernesto Laclau presents populism as an emancipatory social force through which marginalised groups challenge dominant power structures. Some economists have used the term in reference to governments which engage in substantial public spending financed by foreign loans, resulting in hyperinflation and emergency measures. In popular discourse, the term has sometimes been used synonymously with demagogy, to describe politicians who present overly simplistic answers to complex questions in a highly emotional manner, or with opportunism, to characterise politicians who seek to please voters without rational consideration as to the best course of action.

The term populism came into use in the late 19th century alongside the promotion of democracy. In the United States, it was closely associated with the People's Party, while in the Russian Empire it was linked to the agrarian socialist Narodnik movement. During the 20th century, various parties emerged in liberal democracies that were described as populist. In the 21st century, the term became increasingly popular, used in reference largely to left-wing groups in the Latin American pink tide, right-wing groups in Europe, and both right and leftist groups in the U.S. In 2017 'populism' has been chosen as the Cambridge Dictionary Word of the Year.[1]

Etymology and common use

Margaret Canovan on how the term populism was used, 1981[2]

The term populism is a vague and contested term that has been used in reference to a diverse variety of phenomena.[3] The term originated as a term of self-designation, being used by members of the People's Party active in the United States during the late 19th century,[4] while in the Russian Empire during the same period a group referred to itself as the narodniki, which has often been translated into English as populists.[5] The Russian and American movements differed in various respects, and the fact that they shared a name was coincidental.[6]

Although the term started out as a self-designation, part of the confusion surrounding it stems from the fact that it has since rarely been used in this way, with few political figures openly describing themselves as "populists".[7] As noted by the political scientist Margaret Canovan, "there has been no self-conscious international populist movement which might have attempted to control or limit the term's reference, and as a result those who have used it have been able to attach it a wide variety of meanings."[8] In this it differs from other political terms, like socialism, which have been widely used as a self-designation by individuals who have then presented their own, internal definitions of the word.[4]

More usually, the term is used against others, often in a pejorative sense to discredit opponents.[9] In being applied in this way, the term "populism" has often been conflated with other concepts like demagoguery and generally presented as something to be "feared and discredited".[10] Some of those who have repeatedly been referred to as "populists" in a pejorative sense have subsequently embraced the term while seeking to shed it of negative connotations.[10] The French far-right politician Jean-Marie Le Pen for instance was often accused of populism and eventually responded by stating that "Populism precisely is taking into account the people's opinion. Have people the right, in a democracy, to hold an opinion? If that is the case, then yes, I am a populist."[10]

Canovan noted that "if the notion of populism did not exist, no social scientist would deliberately invent it; the term is far too ambiguous for that".[11] The confusion surrounding the term has led some scholars to suggest that it should be abandoned by scholarship.[12] In contrast to this view, the political scientists Cas Mudde and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser stated that "while the frustration is understandable, the term populism is too central to debates about politics from Europe to the Americas to simply do away with."[13] Similarly, Canovan noted that the term "does have comparatively clear and definite meanings in a number of specialist areas" and that it "provides a pointer, however shaky, to an interesting and largely unexplored area of political and social experience".[8] The political scientist Ben Stanley noted that "although the meaning of the term has proven controversial in the literature, the persistence with which it has recurred suggests the existence at least of an ineliminable core: that is, that it refers to a distinct pattern of ideas."[14] Although academic definitions of populism have differed, most of them have focused on the idea that it should reference some form of relationship between "the people" and "the elite".[15]

Ideational definition

The ideational definition of populism used by Mudde and Kaltwasser[16]

A common approach to defining populism is known as the ideational approach.[13] In this definition, populism is applied to politicians and groups which make appeals to "the people" who they then contrast against "the elite".[13] Daniele Albertazzi and Duncan McDonnell define populism as an ideology that "pits a virtuous and homogeneous people against a set of elites and dangerous 'others' who are together depicted as depriving (or attempting to deprive) the sovereign people of their rights, values, prosperity, identity, and voice".[17] In this understanding, note Mudde and Kaltwasser, "populism always involves a critique of the establishment and an adulation of the common people",[13] and according to Ben Stanley, populism itself is a product of "an antagonistic relationship" between "the people" and "the elite", and is "latent wherever the possibility occurs for the emergence of such a dichotomy".[18] This understanding conceives of populism as a discourse, ideology, or worldview.[13] These definitions were initially employed largely in Western Europe, although later became increasingly popular in Eastern Europe and the Americas.[13]

In this approach, populism is viewed as a "thin ideology" or "thin-centred ideology" which on its own is seen as too insubstantial to provide a blueprint for societal change. It thus differs from the "thick-centred" or "full" ideologies such as fascism, liberalism, and socialism, which provide more far-reaching ideas about social transformation. As a thin-centred ideology, populism is therefore attached to a thick-ideology by populist politicians.[19] According to Stanley, "the thinness of populism ensures that in practice it is a complementary ideology: it does not so much overlap with as diffuse itself throughout full ideologies."[20]

- The existence of two homogeneous units of analysis: 'the people' and 'the elite'.

- The antagonistic relationship between the people and the elite.

- The idea of popular sovereignty.

- The positive valorisation of 'the people' and denigration of 'the elite'.

The ideational definition of populism used by Ben Stanley[21]

As a result of the various different ideologies which populism can be paired with, the forms that populism can take vary widely,[16] and populism itself cannot be positioned on the left–right political spectrum.[22] The ideologies which populism can be paired with can be contradictory, resulting in different forms of populism that can oppose each other.[16] For instance, in Latin America during the 1990s, populism was often associated with politicians like Peru's Alberto Fujimori who promoted neoliberal economics, while in the 2000s it was instead associated with politicians like Venezuela's Hugo Chávez who promoted socialist economics.[23] Populist leaders thus "come in many different shades and sizes" but, according to Mudde and Kaltwasser, share one common element: "a carefully crafted image of the vox populi."[24] Stanley expressed the view that although there are "certain family resemblances" that can be seen between populist groups and individuals, there was "no coherent tradition" unifying all of them.[20]

While many left-wing parties in the early 20th century presented themselves as the vanguard of the proletariat, by the early 21st century left-wing populists were presenting themselves as the "voice of the people" more widely.[25] On the political right, populism is often combined with nationalism, with "the people" and "the nation" becoming fairly interchangeable categories in their discourse.[26]

Populism is, according to Mudde and Kaltwasser, "a kind of mental map through which individuals analyse and comprehend political reality."[16] Mudde noted that populism is "moralistic rather than programmatic".[27] It encourages a binary world-view in which everyone is divided into "friends and foes", with the latter being regarded not just as people who have "different priorities and values" but as being fundamentally "evil".[27] In emphasising one's purity against the corruption and immorality of "the elite", from which "the people" must remain pure and untouched, populism prevents compromise between different groups.[27]

The people

Political scientist Cas Mudde[28]

In simplifying the complexities of reality, the concept of "the people" is vague and flexible,[29] with this plasticity benefitting populists who are thus able to "expand or contract" the concept "to suit the chosen criteria of inclusion or exclusion" at any given time.[20] In employing the concept of "the people", populists can encourage a sense of shared identity among different groups within a society and facilitate their mobilisation toward a common cause.[29] One of the ways that populists employ the understanding of "the people" is in the idea that "the people are sovereign", that in a democratic state governmental decisions should rest with the population and that if they are ignored then they might mobilize or revolt.[30] This is the sense of "the people" employed in the late 19th century United States by the People's Party and which has also been used by later populist movements in that country.[30]

A second way in which "the people" is conceived by populists combines a socioeconomic or class based category with one that refers to certain cultural traditions and popular values.[30] The concept seeks to vindicate the dignity of a social group who regard themselves as being oppressed by a dominant "elite" who are accused of treating "the people's" values, judgements, and tastes with suspicion or contempt.[30] A third use of "the people" by populists employs it as a synonym for "the nation", whether that national community be conceived in either ethnic or civic terms. In such a framework, all individuals regarded as being "native" to a particular state, either by birth or by ethnicity, could be considered part of "the people".[31]

Populism typically entails "celebrating them as the people", in Stanley's words.[32] The political scientist Paul Taggart proposed the term "the heartland" to better reflect what populists often mean in their rhetoric.[33] According to Taggart, "the heartland" was the place "in which, in the populist imagination, a virtuous and unified population resides".[34] Who this "heartland" is can vary between populists, even within the same country. For instance, in Britain, the centre-right Conservative Party conceived of "Middle England" as its heartland, while the far-right British National Party conceived of the "native British people" as its heartland.[35] Mudde noted that for populists, "the people" "are neither real nor all-inclusive, but are in fact a mythical and constructed sub-set of the whole population".[35] They are an imagined community, much like the imagined communities embraced and promoted by nationalists.[35]

Populism often entails presenting "the people" as the underdog.[32] Populists typically seek to reveal to "the people" how they are oppressed.[35] In doing so, they do not seek to change "the people", but rather seek to preserve the latter's "way of life" as it presently exists, regarding it as a source of good.[28] Although populist leaders often present themselves as representatives of "the people", they often come from elite strata in society; examples like Berlusconi, Fortuyn, and Haider were all well-connected to their country's political and economic elites.[36]

The elite

Anti-elitism is a characteristic feature of populism.[38] In populist discourse, the "fundamental distinguishing feature" of "the elite" is that it is in an "adversarial relationship" with "the people".[39] In defining "the elite", populists often condemn not only the political establishment, but also the economic elite, cultural elite, and the media elite, which they present as one homogenous, corrupt group.[40] When operating in liberal democracies, populists often condemn dominant political parties as part of "the elite" but at the same time do not reject the party political system altogether, instead either calling for or claiming to be a new kind of party different from the others.[35] As part of their anti-elitist attitude, many populists adhere to conspiracy theories about how the elites control the country.[41]

Although condemning almost all those in positions of power within a given society, populists often exclude both themselves and those sympathetic to their cause even when they too are in positions of power.[37] For instance, the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ), a right-wing populist group, regularly condemned "the media" in Austria for defending "the elite", but excluded from that the Kronen Zeitung, a widely read tabloid that supported the FPÖ and its leader Jörg Haider.[37]

When populists take governmental power, they are faced with a challenge in that they now represent a new elite. In such cases—like Chávez in Venezuela and Vladimír Mečiar in Slovakia—populists retain their anti-establishment rhetoric by making changes to their concept of "the elite" to suit their new circumstances, alleging that real power is not held by the government but other powerful forces who continue to undermine the populist government and the will of "the people" itself.[37] In these instances, populist governments often conceptualise "the elite" as those holding economic power.[42] In Venezuela, for example, Chávez blamed the economic elite for frustrating his reforms, while in Greece, the left-wing populist Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras accused "the lobbyists and oligarchs of Greece" of undermining his administration.[42] In populist instances like these, the claims made have some basis in reality, as business interests seek to undermine leftist-oriented economic reform.[42]

Although left-wing populists who combine populist ideas with forms of socialism most commonly present "the elite" in economic terms, the same strategy is also employed by some right-wing populists.[42] In the United States during the late 2000s, the Tea Party movement—which presented itself as a defender of the capitalist free market—argued that big business, and its allies in Congress, seeks to undermine the free market and kill competition by stifling small business.[42] Among some 21st century right-wing populists, "the elite" are presented as being political progressives committed to political correctness.[44] The Dutch right-wing populist leader Pim Fortuyn referred to this as the "Church of the Left".[44]

In some instances, particularly in Latin America, "the elites" are conceived not just in economic but also in ethnic terms, representing what political scientists have termed ethnopopulism.[45] In Bolivia, for example, the left-wing populist leader Evo Morales juxtaposed the mestizo and indigenous "people" against an overwhelmingly European "elite",[46] declaring that "We Indians [i.e. indigenous people] are Latin America's moral reserve".[43] In the Bolivian case, this was not accompanied by a racially exclusionary approach, but with an attempt to built a pan-ethnic coalition which included European Bolivians against the largely European Bolivian elite.[47] In areas like Europe where nation-states are more ethnically homogenous, this ethnopopulist approach is rare given that the "people" and "elite" are typically of the same ethnicity.[43]

In various instances, populists claim that "the elite" is working against the interests of the country.[42] In the European Union (EU), for instance, various populist groups allege that their national political elites put the interests of the EU itself over those of their own nation-states.[42] Similarly, in Latin America populists often charge political elites with championing the interests of the United States over those of their own countries.[48] Another common tactic among populists, particularly in Europe, is the accusation that "the elites" place the interests of immigrants above those of the native population.[46] In instances where populists are also anti-Semitic, such as Jobbik in Hungary and Attack in Bulgaria, the elites are accused of favouring Israeli and wider Jewish interests above those of the national group, with some instances in which "the elite" is accused of being made up of many Jews as well.[46] When populists emphasise ethnicity as part of their discourse, "the elite" can sometimes be presented as "ethnic traitors".[32]

The general will

A third component of the ideational approach to populism is the idea of the general will, or volonté générale.[49] An example of this populist understanding of the general will can be seen in Chávez's 2007 inaugural address, when he stated that "All individuals are subject to error and seduction, but not the people, which possesses to an eminent degree of consciousness of its own good and the measure of its independence. Because of that its judgement is pure, its will is strong, and none can corrupt or even threaten it."[50] For populists, the general will of "the people" is something that should take precedence over the preferences of "the elite".[51]

As noted by Stanley, the populist idea of the general will is connected to ideas of majoritarianism and authenticity.[51] Highlighting how populists appeal to the ideals of "authenticity and ordinariness", he noted that what was most important to populists was "to appeal to the idea of an authentic people" and to cultivate the idea that they are the "genuine" representatives of "the people".[32] In doing so they often emphasise their physical proximity to "the people" and their distance from "the elites".[32]

In emphasising the general will, many populists share the critique of representative democratic government previously espoused by the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau.[50] This approach regards representative governance as an aristocratic and elitist system in which a country's citizens are regarded as passive entities. Rather than choosing laws for themselves, these citizens are only mobilized for elections in which their only option is to select their representatives rather than taking a more direct role in legislation and governance.[52] Populists often favour the use of direct democratic measures such as referenda and plebiscites.[53] For this reason, Mudde and Kaltwasser suggested that that "it can be argued that an elective affinity exists between populism and direct democracy",[52] although Stanley cautioned that "support for direct democracy is not an essential attribute of populism."[51] Populist notions of the "general will" are usually based on the idea of "common sense".[54]

Populism versus elitism and pluralism

Stanley noted that rather than being restricted purely to populists, appeals to "the people" had become "an unavoidable aspect of modern political practice", with elections and referenda predicated on the notion that "the people" decide the outcome.[21] Thus, a critique of the ideational definition of populism is that it becomes too broad and can potentially apply to all political actors and movements. Responding to this critique, Mudde and Kaltwasser argued that the ideational definition did allow for a "non-populism" in the form of both elitism and pluralism.[55]

Elitists share the populist binary division but reverse the associations. Whereas populists regard the elites as bad and the common people as good, elitists view "the people" as being vulgar, immoral, and dangerous and "the elites" as being morally, culturally, and intellectually superior.[56] Elitists want politics to be largely or entirely an elite affair; some—like Spain's Francisco Franco and Chile's Augusto Pinochet—reject democracy altogether, while others—like Spain's José Ortega y Gasset and Austria's Joseph Schumpeter—support a limited model of democracy.[57]

Pluralism differs from both elitism and populism by rejecting any dualist framework, instead viewing society as a broad array of overlapping social groups, each with their own ideas and interests. In this context, diversity is seen not as a weakness but a strength.[58] Pluralists argue that political power should not be held by any single group—whether defined by their gender, ethnicity, economic status, or political party membership etc—and should instead be distributed. Pluralists encourage governance through compromise and consensus in order to reflect the interests of as many of these groups as possible.[59] Some politicians do not seek to demonise a social elite; for many conservatives for example, the social elite are regarded as the bulwark of the traditional social order, while for some liberals, the social elite are perceived as an enlightened legislative and administrative cadre.[39]

Other definitions

The popular agency definition to populism uses the term in reference to a democratic way of life that is built on the popular engagement of the population in political activity. In this understanding, populism is usually perceived as a positive factor in the mobilization of the populace to develop a communitarian form of democracy.[60] This approach to the term is common among historians in the United States and those who have studied the late 19th century Populist Party in the US.[60]

.jpg)

The Laclauan definition of populism, so called after the Argentinian political theorist Ernesto Laclau who developed it, uses the term in reference to what proponents regard as an emancipatory force that is the essence of politics.[60] In this concept of populism, it is believed to mobilise excluded sectors of society against dominant elites and changing the status quo.[60] Laclau's initial emphasis was on class antagonisms arising between different classes, although he later altered his perspective to claim that populist discourses could arise from any part of the socio-institutional structure".[18] This definition is popular among critics of liberal democracy and is widely used in critical studies and in studies of West European and Latin American politics.[60]

The socioeconomic definition of populism applies the term to what it regards as an irresponsible form of economic policy by which a government engages in a period of massive public spending financed by foreign loans, after which the country falls into hyperinflation and harsh economic adjustments are then imposed.[61] This use of the term was used by economists like Rudiger Dornbusch and Jeffrey Sachs and was particularly popular among scholars of Latin America during the 1980s and 1990s.[60] Since that time, this definition continued to be used by some economists and journalists, particularly in the US, but was uncommon among other social sciences.[62]

An additional approach applies the term populism to a political strategy in which a charismatic leader seeks to govern based on direct and unmediated connection with their followers.[62] This is a definition of the term that is popular among scholars of non-Western societies.[62] Mudde suggested that although the idea of a leader having direct access to "the people" was a common element among populists, it is best regarded as a feature which facilitates rather than defines populism.[33]

In popular discourse, populism is sometimes used in a negative sense in reference to politics which involves promoting extremely simple solutions to complex problems in a highly emotional manner.[63] Mudde suggested that this definition "seems to have instinctive value" but was difficult to employ empirically because almost all political groups engage in sloganeering and because it can be difficult to differentiate an argument made emotionally from one made rationally.[63] Mudde thought that this phenomenon was better termed demagogy rather than populism.[15] Another use of the term in popular discourse is to describe opportunistic policies designed to quickly please voters rather than deciding a more rational course of action.[63] Examples of this would include a governing political party lowering taxes before an election or promising to provide things to the electorate which the state cannot afford to pay for.[64] Mudde suggested that this phenomenon is better described as opportunism rather than populism.[63]

Some scholars argue that populist organizing for empowerment represents the return of older "Aristotelian" politics of horizontal interactions among equals who are different, for the sake of public problem solving.[65][66]

Populist mobilization

There are three forms of political mobilization which populists have adopted: that of the populist leader, the populist political party, and the populist social movement.[67] The reasons why voters are attracted to populists differ, but common catalysts for the rise of populists include dramatic economic decline or a systematic corruption scandal that damages established political parties.[68] For instance, the Great Recession of 2007 and its impact on the economies of southern Europe was a catalyst for the rise of Syriza in Greece and Podemos in Spain, while the Mani pulite corruption scandal of the early 1990s played a significant part in the rise of the Italian populist Silvio Berlusconi.[68] Another catalyst for the growth of populism is a widespread perception among voters that the political system is unresponsive to them.[69] This can arise when elected governments introduce policies that are unpopular with their voters but which are implemented because they are considered to be "responsible" or imposed by supra-national organisations; in Latin America, for example, many countries passed unpopular economic reforms under pressure form the International Monetary Fund and World Bank while in Europe, many countries in the European Union were pushed to implement unpopular economic austerity measures by the union's authorities.[70]

The populist leader

The populist leader is, according to Mudde and Kaltwasser "the quintessential form of populist mobilization".[73] These individuals campaign and attract support on the basis of their own personal appeal.[73] Their supporters then develop a perceived personal connection with the leader.[73] For these leaders, populist rhetoric allows them to claim that they have a direct relationship with "the people",[74] and in many cases they claim to be a personification of "the people" themselves,[73] presenting themselves as the vox populi or "voice of the people".[75] The overwhelming majority of populist leaders have been men,[73] although there have been various females occupying this role.[76] Most of these female populist leaders gained positions of seniority through their connections to previously dominant men; Eva Perón was the wife of Juan Perón, Marine Le Pen the daughter of Jean-Marie Le Pen, Keiko Fujimori the daughter of Alberto Fujimori, and Yingluck Shinawatra the sister of Thaksin Shinawatra.[77]

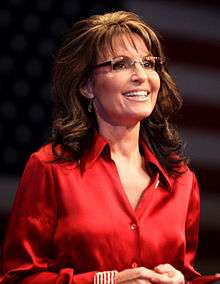

Populist leaders often present themselves as men of action rather than men of words, talking of the need for "bold action" and "common sense solutions" to issues which they call "crises".[72] Male populist leaders often express themselves using simple and sometimes vulgar language in an attempt to present themselves as "the common man" or "one of the boys" to add to their populist appeal.[78] An example of this is Umberto Bossi, the leader of the right-wing populist Italian Lega Nord, who at rallies would state "the League has a hard-on" while putting his middle-finger up as a sign of disrespect to the government in Rome.[79] Another recurring feature of male populist leaders is the emphasis that they place on their own virility.[72] An example of this is the Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, who bragged about his bunga bunga sex parties and his ability to seduce young women.[72] Among female populist leaders, it is more common for them to emphasise their role as a wife and mother.[71] The US right-wing populist Sarah Palin for instance referred to herself as a "hockey mom" and a "mama grizzly",[71] while Australian right-wing populist Pauline Hanson stated that "I care so passionately about this country, it's like I'm its mother. Australia is my home and the Australian people are my children."[71]

Populist leaders typically portray themselves as outsiders who are separate from the "elite". Female populist leaders sometimes reference their gender as setting them apart from the dominant "old boys' club",[80] while in Latin America a number of populists, such as Evo Morales and Alberto Fujimori, emphasised their non-white ethnic background to set them apart from the white-dominated elite.[47] In instances where wealthy business figures promote populist sentiments, such as Ross Perot, Thaksin Shinawatra, or Silvio Berlusconi, it can be difficult to present themselves as being outside the elite, however this is achieved by portraying themselves as being apart from the political, if not the economic elite, and portraying themselves as reluctant politicians.[81] Mudde and Kaltwasser noted that "in reality, most populist leaders are very much part of the national elite", typically being highly educated, upper-middle class, middle-aged males from the majority ethnicity.[82] Mudde and Kaltwasser suggested that "true outsiders" to the political system are rare, although cited instances like Venezuela's Chávez and Chile's Fujimori.[83] More common is that they are "insider-outsiders", strongly connected to the inner circles of government but not having ever been part of it.[84] The Dutch right-wing populist Geert Wilders had for example been a prominent back-bench MP for many years before launching his populist Party for Freedom.[77] Only a few populist leaders are "insiders", individuals who have held leading roles in government prior to portraying themselves as populists.[85] One example is Thaksin Shinawatra, who was twice deputy prime minister of Thailand before launching his own populist political party;[85] another is Rafael Correa, who served as the Ecuadorean finance minister before launching a left-wing populist challenge.[77]

Populist leaders are sometimes also characterised as strongmen or—in Latin American countries—as caudillos.[86] In a number of cases, such as Argentina's Perón or Venezuela's Chávez, these leaders have military backgrounds which contribute to their strongman image.[86] Other populist leaders have also evoked the strongman image without having a military background; these include Italy's Berlusconi, Slovakia's Mečiar, and Thailand's Thaksin Shinawatra.[86] Populism and strongmen are not intrinsically connected, however; as stressed by Mudde and Kaltwasser, "only a minority of strongmen are populists and only a minority of populists is a strongman".[86] Rather than being populists, many strongmen—such as Spain's Francisco Franco—were elitists who led authoritarian administrations.[86]

In most cases, these populist leaders built a political organisation around themselves, typically a political party, although in many instances these remain dominated by the leader.[87] These individuals often give a populist movement its political identity, as is seen with movements like Fortuynism in the Netherlands, Peronism in Argentina, Berlusconism in Italy and Chavismo in Venezuela.[73] Populist mobilization is not however always linked to a charismatic leadership.[88] Mudde and Kaltwasser suggested that populist personalist leadership was more common in countries with a presidential system rather than a parliamentary one because these allow for the election of a single individual to the role of head of government without the need for an accompanying party.[89] Examples where a populist leader has been elected to the presidency without an accompanying political party have included Peron in Argentina, Fujimori in Chile, and Rafael Correa in Ecuador.[89]

Populist political parties

A second form of mobilization is through the form of the populist political party. Populists are not generally opposed to political representation, but merely want their own representatives, those of "the people", in power.[90] In various cases, non-populist political parties have transitioned into populist ones; the elitist Socialist Unity Party of Germany, a Marxist-Leninist group which governed East Germany, later transitioned after German re-unification into a populist party, The Left.[91] In other instances, such as the Austrian FPÖ and Swiss SVP, a non-populist party can have a populist faction which later takes control of the whole party.[92] In some examples where a political party has been dominated by a single charismatic leader, the latter's death has served to unite and strengthen the party, as with Argentina's Justicialist Party after Juan Perón's death in 1974, or the United Socialist Party of Venezuela after Chávez's death in 2013.[93] In other cases, a populist party has seen one strong centralising leader replace another, as when Marine Le Pen replaced her father Jean-Marie as the leader of the National Front in 2011, or when Heinz-Christian Strache took over from Haider as chair of the Freedom Party of Austria in 2005.[94]

Many populist parties achieve an electoral breakthrough but then fail to gain electoral persistence, with their success fading away at subsequent elections.[95] In various cases, they are able to secure regional strongholds of support but with little support elsewhere in the country; the Alliance for the Future of Austria (BZÖ) for instance gained national representation in the Austrian parliament solely because of its strong support in Carinthia.[95] Similarly, the Belgian Vlaams Belang party has its stronghold in Antwerp, while the Swiss People's Party has its stronghold in Zurich.[95]

Populist social movements

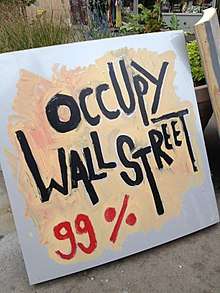

The third form is that of the populist social movement. Populist social movements are comparatively rare, as most social movements focus on a more restricted social identity or issue rather than identifying with "the people" more broadly.[90] However, after the Great Recession of 2007 a number of populist social movements emerged, expressing public frustrations with national and international economic systems. These included the Occupy movement, which originated in the US and used the slogan "We are the 99%", and the Spanish Indignados movement, which employed the motto: "real democracy now – we are not goods in the hands of politicians and bankers".[96]

Few populist social movements survive for more than a few years, with most examples, like the Occupy movement, petering out after their initial growth.[93] In some cases, the social movement fades away as a strong leader emerges from within it and moves into electoral politics.[93] An example of this can be seen with the India Against Corruption social movement, from which emerged Arvind Kejriwal, who founded the Aam Aadmi Party ("Common Man Party").[93] Another is the Spanish Indignados movement which appeared in 2011 before spawning the Podemos party led by Pablo Iglesias Turrión.[97]

Populism and other themes

Canovan proposed that seven different types of populism could be discerned. Three of these were forms of "agrarian populism"; these included farmers' radicalism, peasant movements, and intellectual agrarian socialism.[98] The other four were forms of "political populism", representing populist dictatorship, populist democracy, reactionary populism, and politicians' populism.[98] She noted that these were "analytical constructs" and that "real-life examples may well overlap several categories",[98] adding that no single political movement fitted into all seven categories.[99]

Democracy and populism

There have been intense debates about the relationship between populism and democracy.[100] Some regard populism as being an intrinsic danger to democracy; others regard it as the only "true" form of democracy.[100]

Mudde and Kaltwasser argued that "populism is essentially democratic, but at odds with liberal democracy."[101] It undermines the tenets of liberal democracy by rejection notions of pluralism and the idea that anything should constrain the "general will" of "the people".[101] In practice, populists operating in liberal democracies often criticised the independent institutions designed to protect the fundamental rights of minorities, particularly the judiciary and the media.[101] The Italian populist Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi for instance criticised the Italian judiciary for defending the rights of communists.[101] In countries like Hungary, Ecuador, and Venezuela, populist governments have curtailed the independent media.[102] Minorities have often suffered as a result; in Europe in particular, ethnic minorities have had their rights undermined by populism, while in Latin America it is political opposition groups who have been undermined by popular governments.[103] In several instances—such as Orban in Hungary—the populist leader has set the country on a path of de-democratisation by changing the constitution to centralise increasing levels of power in the head of government.[104]

At the same time, populism can serve as a democratic corrective by contributing to the mobilization of social groups who feel excluded from political decision making.[105] When some populists have taken power—most notable Chávez in Venezuela—they have enhanced the use of direct democracy through the regular application of referenda.[106]

Even when not elected into office, populist parties can have an impact in shaping the national political agenda; in Western Europe, parties like the French National Front and Danish People's Party did not generally get more than 10 or 20% of the national vote, but mainstream parties shifted their own policies to meet the populist challenge.[107]

Mainstream responses to populism

Mainstream political forces have responded to populist challengers in various ways. In some cases, they have sought to co-operate or build alliances with the populists. In the United States, for example, various Republican Party figures aligned themselves with the Tea Party movement, while in countries like Finland and Austria populist parties have taken part in governing coalitions.[108] A more common approach has been for mainstream parties to openly attack the populists and construct a cordon sanitaire to prevent them from gaining political office.[108] While mainstream parties may continue to hold their ideological positions, evidence from the United Kingdom suggests that mainstream politicians may adopt a populist political style.[109] In some cases, when the populists have taken power, their political rivals have sought to violently overthrow them; this was seen in the 2002 Venezuelan coup d'état attempt, when mainstream groups worked with sectors of the military to unseat Hugo Chávez's government.[108]

Once populists are in political office in liberal democracies, the judiciary can play a key role in blocking some of their more illiberal policies, as has been the case in Slovakia and Poland.[110] The mainstream media can play an important role in blocking populist growth; in a country like Germany, the mainstream media is for instant resolutely anti-populist, opposing populist groups whether left or right.[110] Mudde and Kaltwasser noted that there was an "odd love-hate relationship between populist media and politicians, sharing a discourse but not a struggle".[111] In certain countries, certain mainstream media outlets have supported populist groups; in Austria, the Kronen Zeitung played a prominent role in endorsing Haider, in the United Kingdom the Daily Express supported the UK Independence Party, while in the United States, Fox News gave much positive coverage and encouragement to the Tea Party movement.[110]

Mudde and Kaltwasser suggested that to deflate the appeal of populism, those government figures found guilty of corruption need to be seen to face adequate punishment.[112] They also argued that stronger rule of law and the elimination of systemic corruption were also important facets in preventing populist growth.[113] They believed that mainstream politicians wishing to reduce the populist challenge should be more open about the restrictions of their power, noting that those who backed populist movements were often frustrated with the dishonesty of established politicians who "claim full agency when things go well and almost full lack of agency when things go wrong".[114] They also suggested that the appeal of populism could be reduced by wider civic education in the values of liberal democracy and the relevance of pluralism.[114] What Mudde and Kaltwasser believed was ineffective was a full-frontal attack on the populists which presented "them" as "evil" or "foolish", for this strategy plays into the binary division that populists themselves employ.[115] In their view, "the best way to deal with populism is to engage—as difficult as it is—in an open dialogue with populist actors and supporters" in order to "better understand the claims and grievances of the populist elites and masses and to develop liberal democratic responses to them."[116]

Authoritarianism and populism

Scholars have argued that populist elements have sometimes appeared in authoritarian movements.[117][118][119][120][121][122] Conspiracist scapegoating employed by various populist movements can create "a seedbed for fascism".[123]

National Socialist populism interacted with and facilitated fascism in interwar Germany.[124] In this case, distressed middle-class populists mobilized their anger against the government and big business during the pre-Nazi Weimar period. The Nazis "parasitized the forms and themes of the populists and moved their constituencies far to the right through ideological appeals involving demagoguery, scapegoating, and conspiracism".[125]

According to Fritzsche:[126]

The Nazis expressed the populist yearnings of middle–class constituents and at the same time advocated a strong and resolutely anti-Marxist mobilization...Against "unnaturally" divisive parties and querulous organized interest groups, National Socialists cast themselves as representatives of the commonwealth, of an allegedly betrayed and neglected German public...Breaking social barriers of status and caste, and celebrating at least rhetorically the populist ideal of the people's community...

At the turn of the 21st century, the pink tide spreading over Latin America was "prone to populism and authoritarianism".[127] Steven Levitsky and James Loxton,[128] as well as Raúl Madrid,[129] stated that Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez and his regional allies used populism to achieve their dominance and later established authoritarian regimes when they were empowered. Such actions, Weyland argues, proves that "Populism, understood as a strategy for winning and exerting state power, inherently stands in tension with democracy and the value that it places upon pluralism, open debate, and fair competition".[130]

Localism and populism

Jane Wills, a Professor of Human Geography in the University of Exeter, argued that the increasing numbers of populist politicians are endorsing localism as the framework for public policy.[131] She defined that populism is the form of politics that involves actions to speak for the people in a register that is more authentic to the experiences and needs of those people.[131] In other words, most likely that Populist Party policies would contradict with parties supporting the elites.[131] She also used anti-politics to describe populist or localist politician because they stood against mainstream politics.[131] She used the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) as an example where UKIP adopted localism into frame working their policies. Mainstream politicians from Conservative, Labour and Liberal Democrat threatened by the rise of UKIP and their adoption on localism policy, in which they increasingly exposed from the emotional connection to the people.[131]

History

Scholars who have studied populism agree that it is a modern phenomenon.[132] Its origins are often traced to the late nineteenth century, when movements termed populist arose in both the Russian Empire and the United States.[132] In this, populism has been linked to the spread of democracy, both as an idea and as a framework for governance.[132]

North America

In North America, populism has often been characterised by regional mobilization and weak organisation.[133] During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, populist sentiments became widespread, particularly in the western provinces of Canada, and in the southwest and Great Plains regions of the United States. In this instance, populism was combined with agrarianism and often known as "prairie populism".[134] For these groups, "the people" were yeomen—small, independent farmers of European descent—while the "elite" were the bankers and politicians of the northeast.[134]

The People's Party of the late 19th century United States is considered to be "one of the defining populist movements";[135] its members were often referred to as the "Populists" at the time.[134] Its radical platform included calling for the nationalisation of railways, the banning of strikebreakers, and the introduction of referenda.[136] The party gained representation in several state legislatures during the 1890s, but was not powerful enough to mount a successful presidential challenge. In the 1896 presidential election, the People's Party supported the Democratic Party candidate William Jennings Bryan; after his defeat, the People's Party's support declined.[137] Other early populist political parties in the United States included the Greenback Party, the Progressive Party of 1912 led by Theodore Roosevelt, the Progressive Party of 1924 led by Robert M. La Follette, Sr., and the Share Our Wealth movement of Huey Long in 1933–1935.[138][139] In Canada, populist groups adhering to a social credit ideology had various successes at local and regional elections from the 1930s to the 1960s, although the main Social Credit Party of Canada never became a dominant national force.[140]

By the mid-20th century, US populism had moved from a largely progressive to a largely reactionary stance, being closely intertwined with the anti-communist politics of the period.[141] In this period, the historian Richard Hofstadter and sociologist Daniel Bell compared the anti-elitism of the 1890s Populists with that of Joseph McCarthy.[142] Although not all academics accepted the comparison between the left-wing, anti-big business Populists and the right-wing, anti-communist McCarthyites, the term "populist" nonetheless came to be applied to both left-wing and right-wing groups that blamed elites for the problems facing the country.[142] Some mainstream politicians in the Republican Party recognised the utility of such a tactic and adopted it; Republican President Richard Nixon for instance popularised the term "silent majority" when appealing to voters.[141] Right-wing populist rhetoric was also at the base of two of the most successful third-party presidential campaigns in the late 20th century, that of George C. Wallace in 1968 and Ross Perot in 1992.[143] These politicians presented a consisted message that a "liberal elite" was threatening "our way of life" and using the welfare state to placate the poor and thus maintain their own power.[143]

In the first decade of the 21st century, two populist movements appeared in the US, both in response to the Great Recession: the Occupy movement and the Tea Party movement.[144] The populist approach of the Occupy movement was broader, with its "people" being what it called "the 99%", while the "elite" it challenged was presented as both the economic and political elites.[145] The Tea Party's populism was Producerism, and thus implicitly racialized, while "the elite" it presented was more party partisan that that of Occupy, being defined largely—although not exclusively—as the Democratic administration of President Barack Obama.[145] The 2016 presidential election saw a wave of populist sentiment in the campaigns of Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump, with both candidates running on anti-establishment platforms in the Democratic and Republican parties, respectively.[146] Both campaigns criticized free trade deals such as the North American Free Trade Agreement and the Trans-Pacific Partnership.[147][148][149] Trump's electoral victory coincided with a similar trend of populism in Europe in 2016.[150]

Pre-modern antecedents

Populism has been identified with aspects of the Protestant Reformation by German historian Peter Blickle, who stresses the tradition of populist, corporative, anti-feudal politics.[151][152] Protestant groups like the Anabaptists formed ideas about ideal theocratic societies, in which peasants would be able to read the Bible themselves. Attempts to establish these societies were made during the German Peasants' War (1524–1525) and the Münster Rebellion (1534–1535). The peasant movement ultimately failed as cities and nobles made their own peace with the princely armies, which restored the old order.[153]

Populist elements appeared in the English Civil War of the mid-17th century, especially among the Levellers. The movement was committed to popular sovereignty, extended suffrage, equality before the law, and religious tolerance. The hallmark of Leveller thought was its populism, as shown by its emphasis on equal natural rights, and their practice of reaching the public through pamphlets, petitions, and vocal appeals to the crowd. [154]

Europe

In the Russian Empire during the late 19th century, the narodnichestvo movement emerged, championing the cause of the empire's peasantry against the governing elites.[155] The movement was unable to secure its objectives, however it inspired other agrarian movements across eastern Europe in the early 20th century.[156] This agrarian populism was quite similar to that of the U.S. People's Party, with both presenting the peasantry as the foundation of society and main source of societal morality.[156]

In the early 20th century, adherents of both Marxism and fascism flirted with populism, but both movements remained ultimately elitist, emphasising the idea of a small elite who should guide and govern society.[156] Among Marxists, the emphasis on class struggle and the idea that the working classes are affected by false consciousness are also antithetical to populist ideas.[156]

In the years following the Second World War, populism was largely absent from Europe, in part due to the domination of elitist Marxism-Leninism in Eastern Europe and a desire to emphasise moderation among many West European political parties.[157] However, over the coming decades, a number of right-wing populist parties emerged throughout the continent.[135] These were largely isolated and mostly reflected a conservative agricultural backlash against the centralization and politicization of the agricultural sector then occurring.[158] These included Guglielmo Giannini's Common Man's Front in 1940s Italy, Pierre Poujade's Union for the Defense of Tradesmen and Artisans in late 1950s France, Hendrik Koekoek's Farmers' Party of the 1960s Netherlands, and Mogens Glistrup's Progress Party of 1970s Denmark.[135] Between the late 1960s and the early 1980s there also came a concerted populist critique of society from Europe's New Left, including from the new social movements and from the early Green parties.[135] However it was only in the late 1990s, according to Mudde and Kaltwasser, that populism became "a relevant political force in Europe", one which could have a significant impact on mainstream politics.[158]

Following the fall of the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc of the early 1990s, there was a rise in populism across much of Central and Eastern Europe.[159] In the first multiparty elections in many of these countries, various parties portrayed themselves as representatives of "the people" against the "elite", representing the old governing Marxist-Leninist parties.[160] The Czech Civic Forum party for instance campaigned on the slogan "Parties are for party members, Civic Forum is for everybody".[160] Many populists in this region claimed that a "real" revolution had not occurred during the transition from Marxist-Leninist to liberal democratic governance in the early 1990s and that it was they who were campaigning for such a change.[161]

At the turn of the 21st century, populist rhetoric became increasingly apparent in Western Europe, where it was often employed by opposition parties.[163] For example, in the 2001 electoral campaign, the Conservative Party leader William Hague accused Tony Blair's governing Labour Party government of representing "the condescending liberal elite". Hague repeatedly referring to it as "metropolitan", implying that it was out of touch with "the people", who in Conservative discourse are represented by "Middle England".[163] Blair's government also employed populist rhetoric; in outlining legislation to curtail fox hunting on animal welfare grounds, it presented itself as championing the desires of the majority against the upper-classes who engaged in the sport.[164]

By the 21st century, European populism was again associated largely with the political right.[26] The term came to be used in reference both to radical right groups like Jörg Haider's FPÖ in Austria and Jean-Marie Le Pen's FN in France, as well as to non-radical right-wing groups like Silvio Berlusconi's Forza Italia or Pim Fortuyn's LPF in the Netherlands.[26] The populist radical right combined populism with authoritarianism and nativism.[158] Conversely, the Great Recession also resulted in the emergence of left-wing populist groups in parts of Europe, most notably the Syriza party which gained political office in Greece and the Podemos party in Spain, displaying similarities with the US-based Occupy movement.[161] Like Europe's right-wing populists, these groups also expressed Eurosceptic sentiment towards the European Union, albeit largely from a socialist and anti-austerity perspective than the nationalist perspective adopted by their right-wing counterparts.[161]

Germany

Friedrich Ludwig Jahn (1778–1852), a Lutheran Minister, a professor at the University of Berlin and the "father of gymnastics", introduced the concept of Volkstum, a racial notion which draws on the essence of a people that was lost during the Industrial Revolution. Adam Mueller went a step further by positing the belief that the state was a larger totality than the government institutions. This paternalistic vision of aristocracy concerned with social orders had a dark side in that the opposite force of modernity was represented by the Jews, who were said to be eating away at the state.[165] Populism also played a role in mobilizing middle class support for the Nazi Party in Weimar Germany.[166] In this case, distressed middle–class populists mobilized their anger against the government and big business during the pre-Nazi Weimar period. According to Fritzsche:

The Nazis expressed the populist yearnings of middle–class constituents and at the same time advocated a strong and resolutely anti-Marxist mobilization... Against "unnaturally" divisive parties and querulous organized interest groups, National Socialists cast themselves as representatives of the commonwealth, of an allegedly betrayed and neglected German public...[b]reaking social barriers of status and caste, and celebrating at least rhetorically the populist ideal of the people's community...[126]

Italy

.jpg)

When Silvio Berlusconi entered politics in 1994 with his new party Forza Italia, he created a new kind of populism focused on media control.[167] Berlusconi and his allies won three elections, in 1994, 2001 and, with his new right-wing People of Freedom party, in 2008; he was Prime Minister of Italy for almost ten years.[168] Throughout its existence, Berlusconi's party was characterised by a strong reliance on the personal image and charisma of its leader—it has therefore been called a "personality party"[169][170] or Berlusconi's "personal party"[171][172][173]—and the skillful use of media campaigns, especially via television.[174] The party's organisation and ideology depended heavily on its leader. Its appeal to voters was based on Berlusconi's personality more than on its ideology or programme.[175]

Italy’s most prominent right-wing populist party is Lega Nord (LN).[176] The League started as a federalist, regionalist and sometimes secessionist party, founded in 1991 as a federation of several regional parties of Northern and Central Italy, most of which had arisen and expanded during the 1980s. LN's program advocates the transformation of Italy into a federal state, fiscal federalism and greater regional autonomy, especially for the Northern regions. At times, the party has advocated for the secession of the North, which it calls Padania.[177][178][179][180] Certain LN members have been known to publicly deploy the offensive slur "terrone", a common pejorative term for Southern Italians that is evocative of negative Southern Italian stereotypes.[177][178][181] With the rise of immigration into Italy since the late 1990s, LN has increasingly turned its attention to criticizing mass immigration to Italy. The LN, which also opposes illegal immigration, is critical of Islam and proposes Italy's exit from the Eurozone. Since 2013, under the leadership of Matteo Salvini, the party has to some extent embraced Italian nationalism and emphasised Euroscepticism, opposition to immigration and other "populist" policies, while forming an alliance with right-wing populist parties in Europe.[182][183][184]

In 2009, former comedian, blogger and activist Beppe Grillo founded the Five Star Movement. It advocates direct democracy and free access to the Internet, and condemns corruption. The M5S's programme also contains elements of both left-wing and right-wing populism and American-style libertarianism. The party is considered populist, ecologist, and partially Eurosceptic.[185] Grillo himself described the Five Star Movement as being populist in nature during a political meeting he held in Rome on 30 October 2013.[186] In the 2013 Italian election the Five Star Movement gained 25.5% of the vote, with 109 deputies and 54 senators, becoming the main populist and Eurosceptic party in the European Union.[187]

The 2018 general election was characterized by a strong showing by populist movements like Salvini’s League and Luigi Di Maio’s Five Stars.[188][189] In June the two populist parties formed a government led by Giuseppe Conte.[190]

United Kingdom

The UK Labour Party under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn has been called populist,[191][192][193] with the slogan "for the many not the few" having been used.[194][195][196] The United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) had been characterised as a right-wing populist party.[197][198][199] After the 2016 UK referendum on membership of the European Union, in which British citizens voted to leave, some have claimed the "Brexit" as a victory for populism, encouraging a flurry of calls for referendums among other EU countries by populist political parties.[200]

Latin America

Mudde and Kaltwasser noted that Latin America has the world's "most enduring and prevalent populist tradition".[201] They suggested that this was the case because it was a region with a long tradition of democratic governance and free elections, but with high rates of socio-economic inequality, generating widespread resentments that politicians can articulate through populism.[202]

The first wave of Latin American populism began at the start of the Great Depression in 1929 and last until the end of the 1960s.[203] In various countries, politicians took power while emphasising "the people": these included Getúlio Vargas in Brazil, Juan Perón in Argentina, and José María Velasco Ibarra in Ecuador.[204] These relied on the Americanismo ideology, presenting a common identity across Latin America and denouncing any interference from imperialist powers.[205]

The second wave took place in the early 1990s.[205] In the late 1980s, many Latin American states were experiencing economic crisis and several populist figures were elected by blaming the elites for this situation.[205] Examples include Carlos Menem in Argentina, Fernando Collor de Mello in Brazil, and Alberto Fujimori in Peru.[205] Once in power, these individuals pursued neoliberal economic strategies recommended by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), stabilizing the economy and ending hyperinflation.[206] Unlike the first wave, the second did not include an emphasis on Americanismo or anti-imperialism.[207]

The third wave began in the final years of the 1990s and continued into the 21st century.[207] Like the first wave, the third made heavy use of Americanismo and anti-imperialism, although this time these themes presented alongside an explicitly socialist program that opposed the free market.[207] Prominent examples included Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, Evo Morales in Bolivia, Rafael Correa in Ecuador, and Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua.[207] These socialist populist governments have presented themselves as giving sovereignty "back to the people", in particular through the formation of constituent assemblies that would draw up new constitutions, which could then be ratified via referendums.[155]

Oceania

During the 1990s, there was a growth in populism in both Australia and New Zealand.[208]

New Zealand

Robert Muldoon, the 31st Prime Minister of New Zealand from 1975 to 1984, had been cited as a populist leader who appealed to the common man and utilised a personality-driven campaign in the 1975 election.[209]

Populism has become a pervasive trend in New Zealand politics since the introduction of the mixed-member proportional voting system in 1996.[210][211] The New Zealand Labour Party's populist appeals in its 1999 election campaign and advertising helped to propel the party to victory in that election.[212] Labour also articulated populism in its 2002 election campaign, helping return the party to government, despise its being entrenched as part of the establishment under attack by other parties employing strongly populist strategies, drawing on their outsider status. Those parties—New Zealand First and United Future—benefited greatly in 2002 from running almost textbook populist advertising campaigns, which helped both parties increase their proportion of the party vote to levels unanticipated at the commencement of the election campaign.[212] The New Zealand National Party made limited attempts at articulating populism in its advertising, but suffered from the legacy of being part of the 1990s establishment.[212]

In preparation for the 2005 election, then-leader of the National Party Don Brash delivered the Orewa Speech in 2004 on allegations of Māori privilege. This speech has been labelled populist due to the polling beforehand which had revealed to the National Party that the topic of race relations was sensitive enough to sway voters, and its perceived intent to exploit long-held grievances in society.[213] The success in the polls granted to the National Party by this speech led to the delivery of a speech dubbed "Orewa 2" the next year, this time on welfare dependency. This second attempt at a populist speech was less successful as voters perceived it as such.[214]

New Zealand First has presented a more lasting populist platform. Long-time party leader Winston Peters has been characterised by some as a populist who uses anti-establishment rhetoric,[215] though in a uniquely New Zealand style.[216][217] New Zealand First takes a centrist approach to economic issues,[210] typical of populist parties, while advocating conservative positions on social issues.[218] Political commentators dispute the party's classification on the ideological spectrum, but state that its dominant attribute is populism.[219] The party's strong opposition to immigration, and policies that reflect that position, as well as its support for multiple popular referenda, all typify its broadly populist approach. Peters has been criticised for reputedly inciting anti-immigration sentiment[216] and capitalising on immigration fears—he has highlighted the threat of immigration in both economic and cultural terms.[220] Some academics have even characterised New Zealand First as a right-wing populist party,[221] in common with parties such as UKIP in Britain.[215]

Africa and Asia

In much of Africa, populism has been a rare phenomenon.[222] In North Africa, populism was associated with the approaches of several political leaders active in the 20th century, most notably Egypt's Gamal Abdel Nasser and Libya's Muammar Gaddafi.[222] However, populist approaches only became more popular in the Middle East during the early 21st century, by which point it became integral to much of the region's politics.[222] Here, it became an increasingly common element of mainstream politics in established representative democracies, associated with longstanding leaders like Israel's Benjamin Netanyahu and Turkey's Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.[223] Although the Arab Spring was not a populist movement itself, populist rhetoric was present among protesters.[224]

In southeast Asia, populist politicians emerged in the wake of the 1997 Asian financial crisis. In the region, various populist governments took power but were removed soon after: these include the administrations of Joseph Estrada in the Philippines, Roh Moo-hyun in South Korea, Chen Shui-bian in Taiwan, and Thaksin Shinawatra in Thailand.[225]

Late 20th and early 21st century growth

Mudde argued that by the early 1990s, populism had become a regular feature in Western democracies.[164] He attributed this to changing perceptions of government that had spread in this period, which in turn he traced to the changing role of the media to focus increasingly on sensationalism and scandals.[226] Since the late 1960s, the emergence of television had allowed for the increasing proliferation of the Western media, with media outlets becoming increasingly independent of political parties.[226] As private media companies have had to compete against each other, they have placed an increasing focus on scandals and other sensationalist elements of politics, in doing so promoting anti-governmental sentiments among their readership and cultivating an environment prime for populists.[227] At the same time, politicians increasingly faced television interviews, exposing their flaws.[228] News media had also taken to interviewing fewer accredited experts, and instead favouring interviewing individuals found on the street as to their views about current events.[228] At the same time, mass media was giving less attention to the "high culture" of elites and more to other sectors of society, as reflected in reality television shows such as Big Brother.[228]

Mudde argued that another reason for the growth of Western populism in this period was the improved education of the populace; since the 1960s, citizens have expected more from their politicians and felt increasingly competent to judge their actions. This in turn has led to an increasingly sceptical attitude toward mainstream politicians and governing groups.[229] In Mudde's words, "More and more citizens think they have a good understanding of what politicians do, and think they can do it better."[230]

Another factor is that in the post-Cold War period, liberal democracies no longer had the one-party states of the Eastern Bloc against which to favourably compare themselves; citizens were therefore increasingly able to compare the realities of the liberal democratic system with theoretical models of democracy, and find the former wanting.[231] There is also the impact of globalisation, which is seen as having seriously limited the powers of national elites.[232] Such factors undermine citizens' belief in the competency of governing elite, opening up space for charismatic leadership to become increasingly popular; although charismatic leadership is not the same as populist leadership, populists have been the main winners of this shift towards charismatic leadership.[230]

Pippa Norris examined two widely held views on the causes of populism growth. The first was the economic insecurity perspective where it is based on the consequences of the transformation of the workforce in post-industrial economies. The other theory was the cultural backlash thesis according to which the rise of populism is a reaction to the previous predominant progressive values. According to Norris, the latter seems more convincing.[233]

See also

References

Footnotes

- ↑ "'Populism' revealed as 2017 Word of the Year by Cambridge University Press". Cambridge University Press. 30 November 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ↑ Canovan 1981, p. 3.

- ↑ Canovan 1981, p. 3; Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 2.

- 1 2 Canovan 1981, p. 5.

- ↑ Canovan 1981, pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Canovan 1981, p. 14.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 2.

- 1 2 Canovan 1981, p. 6.

- ↑ Stanley 2008, p. 101; Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 Stanley 2008, p. 101.

- ↑ Canovan 1981, p. 301.

- ↑ Canovan 1981, p. 5; Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 5.

- ↑ Stanley 2008, p. 100.

- 1 2 Mudde 2004, p. 543.

- 1 2 3 4 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 6.

- ↑ Albertazzi, Daniele; McDonnell, Duncan (2008). "Twenty-First Century Populism" (PDF). Palgrave MacMillan. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015.

- 1 2 Stanley 2008, p. 96.

- ↑ Mudde 2004, p. 544; Stanley 2008, pp. 95, 99–100, 106; Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 Stanley 2008, p. 107.

- 1 2 Stanley 2008, p. 102.

- ↑ Canovan 1981, p. 294; Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 8.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 20.

- ↑ Mudde 2004, pp. 549–50.

- 1 2 3 Mudde 2004, p. 549.

- 1 2 3 Mudde 2004, p. 544.

- 1 2 Mudde 2004, pp. 546–47.

- 1 2 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 9.

- 1 2 3 4 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 10.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Stanley 2008, p. 105.

- 1 2 Mudde 2004, p. 545.

- ↑ Taggart 2000, p. 95.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mudde 2004, p. 546.

- ↑ Mudde 2004, p. 560.

- 1 2 3 4 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 12.

- ↑ Canovan 1981, p. 295.

- 1 2 Stanley 2008, p. 103.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Canovan 1981, p. 296.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 72.

- 1 2 Mudde 2004, p. 561.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, pp. 14, 72.

- 1 2 3 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 14.

- 1 2 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 16.

- 1 2 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, pp. 16–17.

- 1 2 3 Stanley 2008, p. 104.

- 1 2 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 17.

- ↑ Stanley 2008, p. 104; Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 17.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 18.

- ↑ Mudde 2004, p. 543; Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 7.

- ↑ Mudde 2004, pp. 543–44; Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 7.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 7.

- ↑ Mudde 2004, p. 544; Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 7.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, pp. 7–8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 3.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, pp. 3–4.

- 1 2 3 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 4 Mudde 2004, p. 542.

- ↑ Mudde 2004, pp. 542–43.

- ↑ Harry C. Boyte. "Introduction: Reclaiming Populism as a Different Kind of Politics". The Good Society 21.2 (2012): 173–76. Project MUSE. Web. 21 October 2013. <http://muse.jhu.edu/>(login needed to view journal)

- ↑ Harry C. Boyte, "A Different Kind of Politics", Dewey Lecture, University of Michigan, 2002. Online Archived 15 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine. at Project MUSE (login needed to see PDF file)

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, pp. 42–43.

- 1 2 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 100.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 101.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, pp. 101–102.

- 1 2 3 4 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 70.

- 1 2 3 4 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 64.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 43.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 44.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 62.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 69.

- 1 2 3 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 74.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, pp. 64, 66.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 66.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, pp. 69–70.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, pp. 70–71.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, pp. 73–74.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, pp. 74–75.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 75.

- 1 2 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, pp. 75–76.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 63.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 42.

- 1 2 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 58.

- 1 2 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 51.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 55.

- 1 2 3 4 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 56.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, pp. 55–56.

- 1 2 3 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 60.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 48.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, pp. 56–57.

- 1 2 3 Canovan 1981, p. 13.

- ↑ Canovan 1981, p. 289.

- 1 2 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 79.

- 1 2 3 4 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 81.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 82.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 84.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 91.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, pp. 83, 84.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, pp. 93–94.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 98.

- 1 2 3 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 113.

- ↑ Bossetta, Michael (2017-06-28). "Fighting fire with fire: Mainstream adoption of the populist political style in the 2014 Europe debates between Nick Clegg and Nigel Farage". The British Journal of Politics and International Relations. 19 (4): 715–734. doi:10.1177/1369148117715646. ISSN 1369-1481.

- 1 2 3 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 114.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 115.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 110.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 111.

- 1 2 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 112.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 116.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 118.

- ↑ Ferkiss 1957.

- ↑ Dobratz and Shanks–Meile 1988

- ↑ Berlet and Lyons, 2000

- ↑ Fritzsche, Peter (1990). Rehearsals for fascism: populism and political mobilization in Weimar Germany. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195057805. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015.

- ↑ Fieschi, Catherine (2004). Fascism, Populism and the French Fifth Republic: In the Shadow of Democracy. Manchester UP. ISBN 9780719062094. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015.

- ↑ Germani, Gino (1978). Authoritarianism, Fascism, and National Populism. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 9781412817714. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015.

- ↑ Mark Rupert 1997: 96.

- ↑ Fritzsche 1990: 149–50.

- ↑ Berlet 2005.

- 1 2 Fritzsche 1990: 233–35

- ↑ Isbester, Katherine (2011). The Paradox of Democracy in Latin America: Ten Country Studies of Division and Resilience. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. xiii. ISBN 9781442601802.

- ↑ Levitsky, Steven; Loxton, James (30 August 2012). Populism and Competitive Authoritarianism in the Latin America. New Orleans: American Political Science Association.

- ↑ Madrid, Raúl (June 2012). The Rise of Ethnic Politics in Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 178–83. ISBN 9780521153256.

- ↑ Weyland, Kurt; de la Torre, Carlos; Kornblith, Miriam (July 2013). "Latin America's Authoritarian Drift". Journal of Democracy. 24 (3): 18–32. doi:10.1353/jod.2013.0045.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wills, Jane. "Populism, localism and the geography of democracy." Geoforum, Volume 62 (June 2015), pp. 188–89.

- 1 2 3 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 21.

- ↑ Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 22.

- 1 2 3 Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 23.

- 1 2 3 4 Mudde 2004, p. 548.

- ↑ Canovan 1981, p. 17.

- ↑ Canovan 1981, pp. 17–18, 44–46; Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017, p. 23.

- ↑ Steven J. Rosenstone, Third parties in America (Princeton University Press, 1984)