Nicolás Maduro

| Nicolás Maduro | |

|---|---|

Maduro in 2015 | |

| 46th President of Venezuela | |

|

Assumed office 5 March 2013 Interim: 5 March 2013 – 19 April 2013 | |

| Vice President |

Jorge Arreaza (2013–2016) Aristóbulo Istúriz (2016–2017) Tareck El Aissami (2017–2018) Delcy Rodríguez (since 2018) |

| Preceded by | Hugo Chávez |

| Secretary General of the Non-Aligned Movement | |

|

Assumed office 17 September 2016 | |

| Preceded by | Hassan Rouhani |

| President pro tempore of the Union of South American Nations | |

|

In office 23 April 2016 – 21 April 2017 | |

| Preceded by | Tabaré Vázquez |

| Succeeded by | Mauricio Macri |

| Vice President of Venezuela | |

|

In office 13 October 2012 – 5 March 2013 | |

| President | Hugo Chávez |

| Preceded by | Elías Jaua |

| Succeeded by | Jorge Arreaza |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

|

In office 9 August 2006 – 15 January 2013 | |

| President | Hugo Chávez |

| Preceded by | Alí Rodríguez Araque |

| Succeeded by | Elías Jaua |

| President of the National Assembly of Venezuela | |

|

In office 5 January 2005 – 7 August 2006 | |

| Preceded by | Francisco Ameliach |

| Succeeded by | Cilia Flores |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Nicolás Maduro Moros 23 November 1962 Caracas, Venezuela |

| Political party |

United Socialist Party (2007–present) Fifth Republic Movement (before 2007) |

| Spouse(s) |

Adriana Guerra Angulo (div.) |

| Children | Nicolás Maduro Guerra |

| Residence | Miraflores Palace |

| Signature |

|

| Website | Official website |

Nicolás Maduro Moros (Spanish: [nikoˈlas maˈðuɾo ˈmoɾos];[1] born 23 November 1962) is a Venezuelan politician who has served as the 63rd President of Venezuela since 2013 and previously served under President Hugo Chávez as Minister of Foreign Affairs from 2006 to 2013 and as Vice President of Venezuela from 2012 to 2013.

Starting off as a bus driver, Maduro rose to become a trade union leader before being elected to the National Assembly in 2000. He was appointed to a number of positions within the Venezuelan government under Chávez, ultimately being made Foreign Minister in 2006. He was described during this time as the "most capable administrator and politician of Chávez's inner circle".[2] After Chávez's death was announced on 5 March 2013, Maduro assumed the powers and responsibilities of the President. A special election was held on 14 April 2013 to elect a new President, and Maduro won with 50.62% of the votes as the candidate of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela. He was formally inaugurated on 19 April.[3]

Maduro has ruled Venezuela by decree since 19 November 2013.[4][5][6][7] His presidency has coincided with a decline in Venezuela's socioeconomic status, with crime, inflation, poverty and hunger increasing; analysts have attributed Venezuela's decline to both Chávez and Maduro's economic policies,[8][9][10][11] while Maduro has blamed speculation and an "economic war" waged by his political opponents.[12][13][14][15][16][17] Shortages in Venezuela and decreased living standards resulted in protests beginning in 2014 that escalated into daily marches nationwide, resulting in 43 deaths and a decrease in Maduro's popularity.[18][19][20][21] Maduro's loss of popularity saw the election of an opposition-led National Assembly in 2015 and a movement toward recalling Maduro in 2016, though Maduro still maintains power through loyal political bodies, such as the Supreme Court, National Electoral Council and military.[18][19][22]

After entering a constitutional crisis when the Supreme Tribunal removed power from the National Assembly, months of protests occurred in 2017, leading Maduro to call for a rewrite of the constitution. The Constituent Assembly of Venezuela was elected into office 30 July 2017, with the majority of its members being pro-Maduro.[23][24] On 20 May 2018, Maduro was reelected into the presidency in what the Atlantic Council and Financial Times described as a show election[25][26] which had the lowest voter turnout in Venezuela's modern history.[27]

Like Chávez, Maduro has been accused of authoritarian leadership,[28] with mainstream media describing him as a dictator, especially following the suspension of the recall movement that was directed towards him.[29][30][31] Following the 2017 Venezuelan Constituent Assembly election, the United States sanctioned Maduro, freezing his U.S. assets and prohibited him from entering the country, stating that he was a "dictator".[32] The majority of nations in the Americas and the Western world also refused to recognize the Constituent Assembly and the validity of his 2018 reelection, initiating their own sanctions against him and his administration as well.

Biography

Family background

Nicolás Maduro Moros was born on 23 November 1962 in Caracas, Venezuela, into a working-class family.[33][34][35]

His father, Nicolás Maduro García, who was a prominent trade union leader,[36] died in a motor vehicle accident on 22 April 1989. His mother, Teresa de Jesús Moros, was born in Cúcuta, a Colombian border town at the boundary with Venezuela on "the 1st of June of 1929, as it appears in the National Registry of Colombia".[37]

Nicolás Maduro was raised as a Roman Catholic, although in 2012 it was reported that he was a follower of Indian guru Sathya Sai Baba and previously visited the guru in India in 2005.[38]

Racially, Maduro has indicated that he identifies as mestizo ("mixed [race]"), stating that he includes as a part of his mestizaje ("racial mixture") admixture from the Indigenous peoples of the Americas and Africans.[39] He stated in a 2013 interview that “my grandparents were Jewish, from a Sephardic Moorish background, and converted to Catholicism in Venezuela".[40]

Officially, Maduro was born into a leftist family, with his father being a union leader[33][41] and "militant dreamer of the Movimiento Electoral del Pueblo (MEP)".[42] Maduro was raised in Calle 14, a street in Los Jardines, El Valle, a working-class neighborhood on the western outskirts of Caracas.[37] The only male of four siblings, he had "three sisters, María Teresa, Josefina, and Anita".[42]

Marriages and family

Maduro has been married twice. His first marriage was to Adriana Guerra Angulo, with whom he had his only son, Nicolás Maduro Guerra.[43][44] Maduro Guerra, also known as "Nicolasito", was appointed to several senior government posts: Chief of the Presidency's Special Inspectors Body, head of the National Film School, and a seat in the National Assembly.[45]

He later married Cilia Flores, a lawyer and politician who replaced Maduro as President of the National Assembly in August 2006, when he resigned to become Minister of Foreign Affairs, becoming the first woman to serve as President of the National Assembly.[46] The two had been in a romantic relationship since the 1990s when Flores was Hugo Chávez's lawyer following the 1992 Venezuelan coup d'état attempts[47] and were married in July 2013 months after Maduro became president.[48] While they have no children together, Maduro has three step-children from his wife's first marriage to Walter Ramón Gavidia; Walter Jacob, Yoswel, and Yosser.[49]

Early political career

Education and union work

He attended a public high school, the Liceo José Ávalos, in El Valle.[34][50] His introduction to politics was when he became a member of his high school's student union.[33] According to school records, Maduro never graduated from high school.[41]

In 1979, Maduro was recognized as a person of interest by Venezuelan authorities in the kidnapping of William Niehous,[51] an American employee of Owens-Illinois who was held hostage by leftist militants who would later become close to Hugo Chávez.[52]

Maduro found employment as a bus driver for many years for the Caracas Metro company. He began his political career in the 1980s, by becoming an unofficial trade unionist representing the bus drivers of the Caracas Metro system. He was also employed as a bodyguard for José Vicente Rangel during Rangel's unsuccessful 1983 presidential campaign.[41][53]

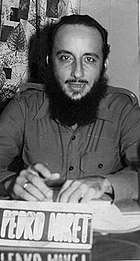

At 24 years of age, Maduro resided in Havana with other militants of leftist organizations in South America who had moved to Cuba in 1986, attending a one-year course at the Escuela Nacional de Cuadros Julio Antonio Mella, a centre of political education directed by the Union of Young Communists.[37] During his time in Cuba, Maduro received vigorous training under Pedro Miret Prieto (es), a senior member of the Politburo of the Communist Party of Cuba who was close to Fidel Castro.[54]

MBR-200

Maduro was allegedly tasked by the Castro government to serve as a "mole" working for the Cuba's Dirección de Inteligencia to approach Hugo Chávez, who was experiencing a burgeoning military career.[55]

In the early 1990s, he joined MBR-200 and campaigned for the release of Chávez when he was jailed for his role in the 1992 Venezuelan coup d'état attempts.[41] In the late 1990s, Maduro was instrumental in founding the Movement of the Fifth Republic, which supported Chávez in his run for president in 1998.[50]

National Assembly

Maduro was elected on the MVR ticket to the Venezuelan Chamber of Deputies in 1998, to the National Constituent Assembly in 1999, and finally to the National Assembly in 2000, at all times representing the Capital District. The Assembly elected him as Speaker, a role he held from 2005 until 2006.

Foreign Minister

On 9 August 2006, Maduro was appointed Minister of Foreign Affairs. According to Rory Carroll, Maduro did not know how to speak any foreign languages while serving as the Minister of Foreign Affairs.[56] During his time as Minister of Foreign Affairs, Venezuela's foreign policy stances included support for Libya under Muammar Gaddafi, and a turnaround in relations with Colombia.[57] Maduro served as the Venezuelan Minister of Foreign Affairs until January 2013.

Vice President of Venezuela

Prior to his appointment to the vice presidency, Maduro had already been chosen by Chávez in 2011 to succeed him in the presidency if he were to die from cancer. This choice was made due to Maduro's loyalty to Chávez and because of his good relations with other chavista hard-liners such as Elías Jaua, former minister Jesse Chacón and Jorge Rodríguez. Bolivarian officials predicted that following Chávez's death, Maduro would have more difficulties politically and that instability in the country would arise.[58]

Chávez appointed Maduro Vice President of Venezuela on 13 October 2012, shortly after his victory in that month's presidential election. Two months later, on 8 December 2012, Chávez announced that his recurring cancer had returned and that he would be returning to Cuba for emergency surgery and further medical treatment. Chávez said that should his condition worsen and a new presidential election be called to replace him, Venezuelans should vote for Maduro to succeed him. This was the first time that Chávez named a potential successor to his movement, as well as the first time he publicly acknowledged the possibility of his demise.[59][60]

Chávez's endorsement of Maduro sidelined Diosdado Cabello, a former Vice President and powerful Socialist Party official with ties to the armed forces, who had been widely considered a top candidate to be Chávez's successor. After Maduro was endorsed by Chávez, Cabello "immediately pledged loyalty" to both men.[61]

Interim president

—Hugo Chávez (December 2012)[57]

Upon the death of Hugo Chávez on 5 March 2013, Maduro assumed the powers and responsibilities of the president. He appointed Jorge Arreaza to take his place as vice president. Since Chávez died within the first four years of his term, the Constitution of Venezuela states that a presidential election had to be held within 30 days of his death.[62][63][64] Maduro was unanimously adopted as the Socialist Party's candidate in that election.[65] At the time of his assumption of temporary power, opposition leaders argued that Maduro violated articles 229, 231, and 233 of the Venezuelan Constitution, by assuming power over the President of the National Assembly.[66][67]

In his speech during the short ceremony in which he formally took over the powers of the president, Maduro said: "Compatriots, I am not here out of personal ambition, out of vanity, or because my surname Maduro is a part of the rancid oligarchy of this country. I am not here because I represent financial groups, neither of the oligarchy nor of American imperialism... I am not here to protect mafias nor groups nor factions."[68][69]

President of Venezuela

The succession to the presidency of Maduro, according to Corales and Penfold, was due to multiple mechanisms that were established by Maduro's predecessor, Hugo Chávez. Initially, oil prices were high enough for Maduro to maintain necessary spending for support, specifically with the military. Foreign ties that were established by Chávez were also utilised by Maduro as he applied skills that he had learned while serving as a foreign minister for his advantage. Finally, the PSUV and government institutions aligned behind Maduro, and "the regime used the institutions of repression and autocracy, also created under Chávez, to become more repressive vis-à-vis the opposition".[70]

On 14 April 2013, Maduro was elected President of Venezuela, narrowly defeating opposition candidate Henrique Capriles with just 1.5% of the vote separating the two candidates. Capriles immediately demanded a recount, refusing to recognize the outcome as valid.[71] Maduro was later formally inaugurated as President on 19 April, after the election commission had promised a full audit of the election results.[3][72] On 24 October 2013, he announced the creation of a new agency, the Vice Ministry of Supreme Happiness, to coordinate all the social programmes.[73]

On 2 May 2016, opposition leaders in Venezuela handed in a petition to the National Electoral Council (CNE) calling for a recall referendum, with the populace to vote on whether to remove Maduro from office.[74] On 5 July 2016, the Venezuelan intelligence service detained five opposition activists involved with the recall referendum, with two other activists of the same party, Popular Will, also arrested.[75] After delays in verification of the signatures, protestors alleged the government was intentionally delaying the process. The government, in response, argued the protestors were part of a plot to topple Maduro.[76] On 1 August 2016, CNE announced that enough signatures had been validated for the recall process to continue. While opposition leaders pushed for the recall to be held before the end of 2016, allowing a new presidential election to take place, the government vowed a recall would not occur until 2017, ensuring the current vice president would potentially come to power.[77]

In May 2017, President Maduro proposed the 2017 Venezuelan Constituent Assembly election, which was later held on 30 July 2017 despite wide international condemnation.[78][79] Upcoming presidential elections, which Maduro would most likely lose, have the possibility of being delayed from their planned dates under a new constitution since no timeline was given for the rewrite.[80][81][82][83] The United States sanctioned President Maduro following the election, labeling him as a "dictator", preventing him from entering the United States.[32]

Rule by decree

Beginning six months after being elected, Maduro has ruled by decree for the majority of his presidency: from 19 November 2013 to 19 November 2014,[4] 15 March 2015 to 31 December 2015, 15 January 2016 to present.[84][85]

Policies

.jpg)

Maduro denies that Venezuela has been facing a crisis.[86] Many of the policies that were in action throughout Maduro's presidency were the same or similar to policies created by his predecessor Hugo Chávez. Maduro stuck to Chávez's policies in order to remain popular to those who find a connection between the two. Despite the increasingly difficult crises facing Venezuela such as a faltering economy and high crime rate, Maduro continued the use of Chávez's policies.[87]

After continuing Chávez's poorly planned policies, Maduro's support among Venezuelans began to decrease, with Bloomberg explaining that he held on to power by placing opponents in jail and impeding upon Venezuela's freedom of press.[88] According to Marsh, instead of making any policy changes, Maduro placed attention on his "hold on power by closing off the legal channels through which the opposition can act".[89] Shannon K. O'Neil of the Council on Foreign Relations stated that "After Chavez's death, Maduro has just continued and accelerated the authoritarian and totalitarian policies of Chavez".[90]

Regarding Maduro's ideology, Professor Ramón Piñango, a sociologist from the Venezuelan University of IESA, "Maduro has a very strong ideological orientation, close to the Communist ideology. Contrary to Diosdado, he is not very pragmatic".[34] Maduro himself has stated that Venezuela must build a more socialist nation, highlighting that the country needs an economic overhaul, a political-military union and government involvement in the workplace.[91]

Domestic

Crime

One of the first important presidential programs of Maduro became the "Safe Homeland" program, a massive police and military campaign to build security in the country. Three thousand soldiers were deployed to decrease homicide in Venezuela, which has one of the highest rates of homicide in Latin America.[92] Most of these troops were deployed in the state of Miranda (Greater Caracas), which has the highest homicide rate in Venezuela. According to the government, in 2012, more than 16,000 people were killed, a rate of 54 people per 100,000, although the Venezuela Violence Observatory, a Venezuelan NGO, claims that the homicide rate was in fact 73 people per 100,000.[92] The government claims that the Safe Homeland program has reduced homicides by 55%.[93][94] The program had to be reinitiated one year later after the program's creator, Miguel Rodríguez Torres, was replaced by Carmen Melendez Teresa Rivas.[95] Murder also increased over the years since the program's initiation according to the Venezuela Violence Observatory, with the murder rate increasing to 82 per 100,000 in 2014.[96]

Economic policies

When elected in 2013, Maduro continued the majority of existing economic policies of his predecessor Hugo Chávez. When entering the presidency, Maduro's Venezuela faced a high inflation rate and large shortages of goods[97][98][99] that was left over from the previous policies of President Chávez.[100][101][102][11]

Maduro blamed capitalism for speculation that is driving high rates of inflation and creating widespread shortages of staples, and often said he was fighting an "economic war", calling newly enacted economic measures "economic offensives" against political opponents he and loyalists state are behind an international economic conspiracy.[103][104][105][106][107][108] However, Maduro has been criticized for only concentrating on public opinion instead of tending to the practical issues economists have warned the Venezuelan government about or creating any ideas to improve the economic situation in Venezuela such as the "economic war".[109][110]

Venezuela was ranked as the top spot globally with the highest misery index score in 2013,[111] 2014,[112] 2015[113][114] and 2016.[115] In 2014, Venezuela's economy entered an economic depression[116] that has continued as of 2017.[89]

Military

Maduro has relied on the military to maintain power since he was initially elected into office.[117] He has promised to make Venezuela a great power by 2050, stating that the Venezuelan military would lead the way to make the country "a powerhouse, of happiness, of equality".[118]

On 12 July 2016, Maduro granted Defense Minister Vladimir Padrino López the power to oversee product transportation, price controls, the Bolivarian missions, while also having his military command five of Venezuela's main ports.[119][120][121] This action performed by President Maduro made General Padrino one of the most powerful people in Venezuela, possibly "the second most powerful man in Venezuelan politics".[120][122][122] The appointment of Padrino was also seen to be similar to the Cuban government's tactic of granting the Cuban military the power to manage Cuba's economy.[120]

According to Nicolás Maduro:[120]

All ministries and government institutions are subordinated to the National Command of the Great Mission for Safe Sovereign and Safe Supply, which is under the command of the President and of the top General, Vladimir Padrino López.

It was the first time since the dictatorship of General Marcos Perez Jimenez in 1958 that a military official has held such power in Venezuela.[121]

Foreign policy

.jpg)

Maduro has accused the United States of intervention in Venezuela several times with his allegations ranging from post-election violence by "neo-Nazi groups", economic difficulties from what he called an "economic war" and various coup plots.[123][124] The United States denied such accusations[124] while analysts have called such allegations by Maduro as a way to distract Venezuelans from their problems.[125]

In early 2015 the Obama administration signed an executive order which imposed targeted sanctions on 7 Venezuelan officials whom the White House argued were instrumental in human rights violations, persecution of political opponents and significant public corruption and said that the country posed an "unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and foreign policy of the United States."[126] Maduro responded to the sanctions in a couple of ways. He wrote an open letter in a full page ad in The New York Times in March 2015, stating that Venezuelans were "friends of the American people" and called President Obama's action of making targeted sanctions on the alleged human rights abusers a "unilateral and aggressive measure".[45][127] Examples of accusations of human rights abuses from the United States to Maduro's government included the murder of a political activist prior to legislative elections in Venezuela.[128] Maduro threatened to sue the United States over an executive order issued by the Obama Administration that declared Venezuela to be a threat to American security.[129] He also planned to deliver 10 million signatures, or signatures from about 1/3 of Venezuela's population, denouncing the United States' decree declaring the situation in Venezuela an "extraordinary threat to US national security".[130][131] and ordered all schools in the country to hold an "anti-imperialist day" against the United States with the day's activities including the "collection of the signatures of the students, and teaching, administrative, maintenance and cooking personnel".[131] Maduro further ordered state workers to apply their signatures in protest, with some workers reporting that firings of state workers occurred due to their rejection of signing the executive order protesting the "Obama decree".[131][132][133][134][135][136] There were also reports that members of Venezuelan armed forces and their families were ordered to sign against the United States decree.[131]

On 6 April 2015, twenty-five (25) ex-presidents issued called Declaración de Panamá,[137] a statement denouncing the VII Cumbre de las Américas, what they called "democratic alteration" in Venezuela, promoted by the government of Nicolas Maduro. The statement calls for the immediate release of "political prisoners" in Venezuela. Among the former heads of government that have called for improvements in Venezuela are: Jorge Quiroga (Bolivia); Sebastián Piñera (Chile): Andrés Pastrana, Álvaro Uribe and Belisario Betancur (Colombia); Miguel Ángel Rodríguez, Rafael Ángel Calderón Guardia, Laura Chinchilla, Óscar Arias, Luis Alberto Monge (Costa Rica), Osvaldo Hurtado (Ecuador); Alfredo Cristiani and Armando Calderón (EL Salvador); José María Aznar (Spain); Felipe Calderón and Vicente Fox (México), Mireya Moscoso (Panamá), Alejandro Toledo (Perú) and Luis Alberto Lacalle (Uruguay).[138]

Maduro has reached out to China for economic assistance while China has funneled billions of dollars from multiple loans into Venezuela.[139] China is Venezuela's second largest trade partner with two-thirds of Venezuelan exports to China composed of oil.[139] According to Mark Jones, a Latin American expert of the Baker Institute, China was "investing for strategic reasons" rather than ideological similarities.[139] The Venezuelan military has also used military equipment from China using the NORINCO VN-4 armoured vehicle against protesters during the 2014–15 Venezuelan protests, ordering hundreds more as a result of the demonstrations.[140][141]

2013 presidential campaign

2018 presidential campaign

Controversies

Protests

Birthplace

|

|

Article 227 of the Constitution of Venezuela

Nicolás Maduro's birthplace and nationality have been questioned several times,[142][143] with some placing doubt that he could hold the office of the presidency, given that Article 227 of the Venezuelan constitution states that "To be chosen has president of the Republic it is required to be Venezuelan by birth, not having another nationality, being over thirty years old, of a secular state and not being in any state or being in another firm position and fulfilling the other requirements in this Constitution.[144] After his triumph in the 2013 presidential elections, opposition deputies warned that they would investigate the double nationality of Maduro.

By 2014, official declarations by the Venezuela government shared four different birthplaces of Maduro.[145] Tachira state's governor José Vielma Mora assured that Maduro was born in El Palotal sector of San Antonio del Táchira and that he had relatives that live in the towns of Capacho and Rubio.[146] The opposition deputy Abelardo Díaz reviewed the civil registry of El Valle, as well as the civil registry referenced by Vielma Mora, without finding any proof or documentation that could confirm Maduro's birthplace.[147] On June 2013, two months after assuming the presidency, Maduro claimed in a press conference in Rome that he was born in Caracas, in Los Chaguaramos, in the San Pedro parish. During an interview with a Spanish journalist, also on June 2013, Elías Jaua claimed that Maduro was born in El Valle parish, in the Libertador Municipality of Caracas.[144]

On October 2013 Tibisay Lucena, head of the National Electoral Council, assured in the Globovisión TV show Vladimir a la 1 that Maduro was born in La Candelaria parish in Caracas, showing copies of the registry presentation book of all the newborns the day when allegedly Maduro was born. In April 2016 during a cadena nacional, Maduro changed his birthplace narrative once more, saying that he was born in Los Chaguaramos, specifically in Valle Abajo, adding that he was baptized in the San Pedro church.[144][148]

On 2016 a group of Venezuelans asked the National Assembly to investigate if Nicolás Maduro was Colombian in an open letter addressed to the National Assembly President Henry Ramos Allup that justified the request by the "reasonable doubts there are around the true origins of Maduro, because, to date, he has refused to show his birth certificate." The 62 petitioners, including former ambassador Diego Arria, businessman Marcel Granier and opposition former military, assuring that according to the Colombian constitution Maduro is "Colombian by birth" for being "the son of a Colombian mother and for having resided" in the neighboring country "during his childhood".[149] The same year several former members of the Electoral Council sent an open letter to Tibisay Lucena requesting to "exhibit publicly, in a printed media of national circulation the documents that certify the strict compliance with Articles 41 and 227 of the Constitution of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, that is to say, the birth certificate and the Certificate of Venezuelan Nationality by Birth of Nicolás Maduro Moros in order to verify if he is Venezuelan by birth and without another nationality". The document mentions that the current president of the CNE incurs in "a serious error, and even an irresponsibility, when she affirms that Maduro's nationality 'is not a motto of the National Electoral Council'" and the signatories also refer to the four different moments in which different politicians have awarded four different places of birth as official.[150] Diario Las Américas claimed to have access to the birth inscriptions of Teresa de Jesús Moros, Maduro's mother, and of José Mario Moros, his uncle, both registered in the parish church of San Antonio of Cúcuta, Colombia.[150]

Opposition deputies have assured that the birth certificate of Maduro must say mandatorily that he is the son of a Colombian mother, which would represent the proof that confirms that the president has a double nationality and that he cannot hold any office under Article 41 of the constitution.[144] Deputy Dennis Fernández has headed a special commission that investigates the origins of the president and has declared that "Maduro's mother is a Colombian citizen" and that the Venezuelan head of State would also be Colombian.[151] The researcher, historian and former deputy Walter Márquez declared months after the presidential elections that Maduro's mother was born in Colombia and not in Rubio, Táchira. Márquez has also declared that Maduro "was born in Bogotá, according to the verbal testimonies of people who knew him as a child in Colombia and the documentary research we did" and what "there are more than 10 witnesses that corroborate this information, five of them live in Bogotá ".[152]

On 28 October 2016, the Supreme Tribunal of Justice issued a ruling stating that according to "incontrovertible" proofs it has "absolute certainty" that Maduro was born in Caracas, in the parish of La Candelaria, known then as the Libertador Department of the Federal District, on November 23, 1962.[144] The ruling does not reproduce Maduro's birth certificate but it quotes a communication signed on 8 June by the Colombian Vice minister of foreign affairs, Patti Londoño Jaramillo, where it states that "no related information was found, nor civil registry of birth, nor citizenship card that allows to infer that president Nicolás Maduro Moros is a Colombian national". The Supreme Court warned the deputies and the Venezuelans that "sowing doubts about the origins of the president" may "lead to the corresponding criminal, civil, administrative and, if applicable, disciplinary consequences" for "attack against the State".[151]

On 11 January 2018, the Supreme Tribunal of Justice of Venezuela in exile decreed the nullity of the 2013 presidential elections after lawyer Enrique Aristeguita Gramcko presented evidence about the presumed non-existence of ineligibility conditions of Nicolás Maduro to be elected and to hold the office of the presidency. Aristeguieta argued in the appeal that, under Article 96, Section B, of the Political Constitution of Colombia, Nicolás Maduro Moros, even in the unproven case of having been born in Venezuela, is "Colombian by birth" because he is the son of a Colombian mother and by having resided in that territory during his youth. The Constitutional Chamber admitted the demand and requested the presidency and the Electoral Council to send a certified copy of the president's birth certificate, in addition to his resignation from Colombian nationality.[153] In March 2018 former Colombian president Andrés Pastrana made reference to the baptism certificate of Maduro's mother, noting that the disclosed document reiterates the Colombian origin of the mother of the president and that therefore Nicolás Maduro has Colombian citizenship.[151]

Conspiracy theories

Maduro and members of his entourage have voiced on several occasions of alleged conspiracies against Maduro and his government. Maduro continued the practice of his predecessor, Hugo Chávez, of denouncing alleged conspiracies and in a period of fifteen months following his election, dozens of conspiracies, some supposedly linked to assassination and coup attempts, were reported by Maduro's government.[154] In this same period, the number of attempted coups claimed by the Venezuelan government outnumbered all attempted and executed coups occurring worldwide in the same period.[155] In TV program La Hojilla, Mario Silva, a TV personality of the main state-run channel Venezolana de Televisión, stated in March 2015 that President Maduro had received about 13 million psychological attacks.[156]

Analysts and observers of such allegations state that Maduro uses such conspiracy theories as a strategy to distract Venezuelans from the root causes of some problems facing his government.[125][154][157][158] According to Foreign Policy, Maduro's predecessor, Hugo Chávez, "relied on his considerable populist charm, conspiratorial rhetoric, and his prodigious talent for crafting excuses" to avoid backlash from troubles Venezuela was facing, with Foreign Policy further stating that for Maduro, "the appeal of reworking the magic that once saved his mentor is obvious".[155] Such conspiracy theories presented by the Venezuelan government have never involved any substantial evidence.[131][154][158]

Andrés Cañizales, researcher from the Andrés Bello Catholic University, pointed that, as a result of the lack of reliable mainstream news broadcasting, most Venezuelan stay informed with social networking services. As a result, fake news and internet hoaxes have a higher impact in Venezuela than in other countries.[159]

United States involvement accusations

In early 2015, the Maduro government accused the United States of attempting to overthrow him. The Venezuelan government performed elaborate actions to respond to such alleged attempts and to convince the public that its claims were true.[155] The reactions included the arrest of Antonio Ledezma in February 2015, forcing American tourists to go through travel requirements and holding military marches and public exercises "for the first time in Venezuela's democratic history".[155] After the United States ordered sanctions to be placed on seven Venezuelan officials for alleged human rights violations, Maduro used anti-US rhetoric to bump up his approval ratings.[160][161] However, according to Venezuelan political scientist Isabella Picón, only about 15% of Venezuelans believed in the alleged coup attempt accusations at the time.[155]

In 2016, Maduro again claimed that the United States was attempting to assist the opposition with a coup attempt. On 12 January 2016, Secretary General of the Organization of American States (OAS), Luis Almagro, threatened to invoke the Inter-American Democratic Charter, an instrument used to defend democracy in the Americas when threatened, when opposition National Assembly member were barred from taking their seats by the Maduro-aligned Supreme Court.[162] Human rights organizations such as Human Rights Watch,[163] and the Human Rights Foundation[164] called for the OAS to invoke the Democratic Charter. After more controversies and pursuing a recall on Maduro, on 2 May 2016, opposition members of the National Assembly met with OAS officials to ask for the body to implement the Democratic Charter.[165] Two days later on 4 May, the Maduro government called for a meeting the next day with the OAS, with Venezuelan Foreign Minister Delcy Rodriguez stating that the United States and the OAS were attempting to overthrow Maduro.[166] On 17 May 2016 in a national speech, Maduro called OAS Secretary General Luis Almagro "a traitor" and stated that he worked for the CIA.[167] Almagro sent a letter rebuking Maduro, and refuting the claim.[168]

Corruption and human rights

On 29 May 2018, a Board of Independent Experts designated by the Organization of American States published a 400 page report stating that Maduro was the alleged leader of human rights violations in Venezuela, supposedly using authoritarianism to maintain a hold on power in the country.[169]

The Board concluded that Maduro was "responsible for dozens of murders, thousands of extra-judicial executions, more than 12,000 cases of arbitrary detentions, more than 290 cases of torture, attacks against the judiciary and a 'state-sanctioned humanitarian crisis' affecting hundreds of thousands of people".[170]

Trial

Maduro was sentenced to 18 years and 3 months in prison on 15 August 2018 by the Supreme Tribunal of Justice of Venezuela in exile, with the exiled high court stating "there is enough evidence to establish the guilt ... [of] corruption and legitimation of capital".[171] The Organization of American States Secretary General, Luis Almagro, supported the verdict and asked for the Venezuelan National Assembly to recognize the Supreme Tribunal in exile's ruling.[172]

Drug trafficking and money laundering incidents

Narcosobrinos incident

Two nephews of Maduro's wife, Efraín Antonio Campo Flores and Francisco Flores de Freitas, were found guilty in a US court of conspiracy to import cocaine in November 2016, with some of their funds possibly assisting Maduro's presidential campaign in the 2013 Venezuelan presidential election and potentially for the 2015 Venezuelan parliamentary elections, with the funds mainly used to "help their family stay in power".[173][174][175] One informant stated that the two often flew out of Terminal 4 of Simon Bolivar Airport, a terminal reserved for the president.[173][174] Due to the fact that the nephews were arrested for narcotics trafficking, the media described the nephews as the "narcosobrinos".[176][177][178][179][180][181] Both nephews were sentenced 18 years in prison on 11 December 2017.[182]

After Maduro's nephews were apprehended by the US Drug Enforcement Administration for the illegal distribution of cocaine on 10 November 2015, Maduro posted a statement on Twitter criticizing "attacks and imperialist ambushes", which was viewed by many media outlets as being directed towards the United States.[183][184] Diosdado Cabello, a senior official in Maduro's government, was quoted as saying the arrests were a "kidnapping" by the United States.[185]

Secretary of the President investigation

In December 2015 following controversial investigations of money laundered drug money by the Bal Harbour Police Department and Glades County Police without the cooperation of the United States Department of Justice, a report from Miami Herald revealed that much of the drug money was ultimately funneled from multiple banks into the Venezuelan Banesco Bank with some of the largest payments wired to the bank. It was found that William Amaro Sanchez, a secretary and longtime friend of Maduro who was described as his "right-hand-man", had over $200,000 of the drug money transferred to his account. Juan Carlos Escort, head of Banesco, denied the allegations, although unnamed Banesco employees told The Miami Herald that it was Amaro's account and provided information that included his account number, full name and Venezuelan government identification number.[186][187]

Following these revelations, Panamanian lawyer and politician Guillermo Cochez called on Panama's Public Ministry to investigate accounts in Banesco related to the Venezuelan government, including accounts belonging to Willam Amaro Sanchez and also possible accounts belonging to relatives of President Maduro's wife, Cilia Flores. After Flores' nephews were arrested by the United States Drug Enforcement Administration, it was discovered that one of the arrested nephews, Efraín Campo Flores, owned a Panamanian company, with Cilia Flores and other relatives belonging to the company's board of directors.[188]

Cabello sanctions

On 18 May 2018, the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) of the United States Department of the Treasury placed sanctions in effect against high-level official Diosdado Cabello. OFAC stated that Cabello and others used their power within the Bolivarian government "to personally profit from extortion, money laundering, and embezzlement", with Cabello allegedly directing drug trafficking activities with Vice President of Venezuela, Tareck El Aissami while dividing drug profits with President Nicolás Maduro. The Office also stated that Cabello would use public information to track wealth individuals who were potentially drug trafficking and steal their drugs and property in order to get rid of potential competition.[189]

Homophobic statements

During a tenth anniversary gathering commemorating the 2002 Venezuelan coup d'état attempt going into the 2012 Venezuelan presidential election, Maduro called opposition members "snobs" and "big faggots".[190][191]

During the presidential campaign of 2013, Maduro used homophobic attacks as a political weapon, calling representatives of the opposition "faggots".[192] Maduro used homophobic speech toward his opponent Henrique Capriles calling him a "little princess" and saying "I do have a wife, you know? I do like women!"[192][193][194]

In December 2014, amid the celebration of 15 years of the "Bolivarian Constitution", Maduro commented on the American drafted bill that would potentially penalize some government officials involved in corruption, drug trafficking and violation of human rights, saying on radio and television, "they grab their visa and where the mess has to shove, insert the visa in the ass".[195]

In April 2015, the Spanish Congress held criticism of the situation in Venezuela, to which Maduro responded "go to your mothers".[196]

Hunger

CLAP program

Luisa Ortega Díaz, Chief Prosecutor of Venezuela from 2007 to 2017 revealed that President Maduro had been profiting from the shortages in Venezuela. The government-operated Local Supply and Production Committee (CLAP), which provides food to impoverished Venezuelans, made contracts with Group Grand Limited, an organization owned by Maduro through front-men Rodolfo Reyes, Álvaro Uguedo Vargas and Alex Saab. Group Grand Limited, a Mexican entity owned by Maduro, would sell foodstuffs to CLAP and receive government funds, enriching Maduro and his associates.[197][198][199]

Displays of indulgence

While Venezuelans were affected by hunger and shortages, Maduro and his government officials publicly shared images of themselves eating luxurious meals that was met with displeasure by Venezuelans.[200] Despite the majority of Venezuelans losing weight due to hunger, members of the Maduro's administration appeared to gain weight.[200]

In November 2017, while giving a lengthy, live broadcast concerning the starvation and poverty crisis within Venezuela; Maduro, unaware he was still being filmed, pulled out an empanada from his desk and began eating it.[201][202] This occurred amid controversy of Maduro gaining weight during the nationwide food and medicine shortage; with many on social media criticizing the publicly-broadcast incident.[203][204]

In September 2018, Maduro received international criticism for eating at Nusret Gökçe's, luxurious Istanbul restaurant. Gökçe, popularly known as Salt Bae, served Maduro and his wife a meat meal, a personalized shirt and a box of cigars with Maduro's name engraved upon it.[200][205]

Jose Zalt wedding incident

At the wedding of Jose Zalt, a Syrian-Venezuelan businessman who owns the clothing brand Wintex, on 14 March 2015, Maduro's son, Nicolas Ernesto Maduro Guerra, was seen being showered with American dollar banknotes at a gathering in the luxurious Gran Melia Hotel in Caracas. The incident caused outrage among Venezuelans, who believed this to be hypocritical of President Maduro, especially since many Venezuelans were experiencing hardships due to the poor state of the economy and Maduro's public denouncements of capitalism.[45][206][207][208][209][210] The incident took place hours after the Venezuelan government military parade conducted against the United States which Maduro's government claims is behind an "economic war" with Venezuela.[208][211]

Odebrecht bribes

In an investigative interview with Euzenando Prazeres de Azevedo, president of Constructora Odebrecht in Venezuela, the executive revealed how Odebrecht paid $35 million to fund Maduro's 2013 presidential campaign if Odebrecht projects would be prioritized in Venezuela.[212] Americo Mata, Maduro's campaign manager, initially asked for $50 million for Maduro, though the final $35 million was settled.[212][213]

Sanctions

Canada

On 22 September 2017, the Canadian government sanctioned members of the Maduro government, including Maduro, preventing Canadian nationals from participating in property and financial deals with him due to the rupture of Venezuela's constitutional order.[214][215]

Panama

On 29 March 2018, Maduro was sanctioned by the Panamanian government for his alleged involvement with "money laundering, financing of terrorism and financing the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction".[216]

United States

On 26 July 2017, thirteen government officials were sanctioned by the United States Department of Treasury due to their involvement with the 2017 Venezuelan Constitutional Assembly election.[217]

After continuing with the Constitutional Assembly election, the United States sanctioned Maduro, becoming one of the few heads of state sanctioned by the United States, with Secretary of the Treasury Steven Mnuchin stating "Maduro is a dictator who disregards the will of the Venezuelan people".[32] Maduro responded, saying he was "proud" of being sanctioned by the United States government.[218]

Drone incident

On 4 August 2018, at least two drones armed with explosives detonated in the area where Maduro was delivering an address to military officers in Venezuela.[219]

Recognition

| Awards and orders | Country | Date | Place | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order of the Liberator | 19 April 2013 | Caracas, Venezuela | Highest decoration of Venezuela, given to every president.[220] | ||

| Order of the Liberator General San Martín | 8 May 2013 | Buenos Aires, Argentina | Highest decoration of Argentina awarded by political ally Cristina Kirchner. Revoked on 11 August 2017 by President Mauricio Macri for "human rights violations".[221] [222] [223] | ||

| Order of the Condor of the Andes | 26 May 2013 | La Paz, Bolivia | Highest decoration of Bolivia.[224] | ||

| Bicentenary Order of the Admirable Campaign | 15 June 2013 | Trujillo, Venezuela | Venezuelan order.[225] | ||

| Star of Palestine | 16 May 2014 | Caracas, Venezuela | Highest decoration of Palestine.[226] | ||

| Order of Augusto César Sandino | 17 March 2015 | Managua, Nicaragua | Highest decoration of Nicaragua.[227] | ||

| Order of José Martí | 18 March 2016 | La Habana, Cuba | Cuban order.[228] | ||

- In 2014, Maduro was named as one of TIME magazine's 100 Most Influential People. In the article, it explained that whether or not Venezuela collapses "now depends on Maduro", saying it also depends on whether Maduro "can step out of the shadow of his pugnacious predecessor and compromise with his opponents".[229]

- In 2016, the Reporters Without Borders (RSF) Top 35 Predators of Press Freedom list placed Maduro as a "predator" to press freedom in Venezuela, with RSF noting his method of "carefully orchestrated censorship and economic asphyxiation" toward media organizations.[230][231]

See also

References

- ↑ In isolation, Nicolás is pronounced [nikoˈlas].

- ↑ de Córdoba, José; Vyas, Kejal (9 December 2012). "Venezuela's Future in Balance". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- 1 2 "Nicolas Maduro sworn in as new Venezuelan president". BBC News. 19 April 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- 1 2 Diaz-Struck, Emilia; Forero, Juan (19 November 2013). "Venezuelan president Maduro given power to rule by decree". The Washington Post. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ↑ "Venezuela: President Maduro granted power to govern by decree". BBC News. 16 March 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ↑ Brodzinsky, Sibylla (15 January 2016). "Venezuela president declares economic emergency as inflation hits 141%". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ↑ Worely, Will (18 March 2016). "Venezuela is going to shut down for a whole week because of an energy crisis". The Independent. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ↑ Osmary Hernandez, Mariano Castillo and Deborah Bloom (February 21, 2017). "Venezuelan food crisis reflected in skipped meals and weight loss". CNN. Retrieved May 28, 2017.

- ↑ Anders Aslund (May 2, 2017). "Venezuela Is Heading for a Soviet-Style Collapse". Foreign Policy. Retrieved May 28, 2017.

- ↑ Loris Zanatta (May 30, 2017). "Cuando el barco se hunde" [When the ship sinks]. La Nación (in Spanish). Retrieved May 28, 2017.

- 1 2 Scharfenberg, Ewald (1 February 2015). "Volver a ser pobre en Venezuela". El Pais. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ↑ "Mr. Maduro in His Labyrinth". The New York Times. 26 January 2015. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ↑ "Venezuela's government seizes electronic goods shops". BBC. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ↑ "Maduro anuncia que el martes arranca nueva "ofensiva económica"". La Patilla. 22 April 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ↑ "Maduro insiste con una nueva "ofensiva económica"". La Nacion. 23 April 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ↑ "Decree powers widen Venezuelan president's economic war". CNN. 20 November 2013. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ↑ Yapur, Nicolle (24 April 2014). "Primera ofensiva económica trajo más inflación y escasez". El Nacional. Archived from the original on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- 1 2 Washington, Richard (22 June 2016). "'The Maduro approach' to Venezuelan crisis deemed unsustainable by analysts". CNBC. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- 1 2 Lopez, Linette. "Why Venezuela is a nightmare right now". Business Insider. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ↑ Faria, Javier. "Venezuelan teen dies after being shot at anti-Maduro protest". Reuters. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ↑ Usborne, David. "Dissent in Venezuela: Maduro regime looks on borrowed time as rising public anger meets political repression". The Independent. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ↑ "A 2016 Presidential Recall Seems Less and Less Likely". Stratfor. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ↑ "What are Venezuelans voting for and why is it so divisive?". BBC News. 30 July 2017. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- ↑ Bronstein, Hugh (July 29, 2017). "Venezuelan opposition promises new tactics after Sunday's vote". Reuters India. Retrieved July 30, 2017.

- ↑ Sen, Ashish Kumar (18 May 2018). "Venezuela's Sham Election". Atlantic Council. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

Nicolás Maduro is expected to be re-elected president of Venezuela on May 20 in an election that most experts agree is a sham

- ↑ "Venezuela's sham presidential election". Financial Times. 16 May 2018. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

The vote, of course, is a sham. Support is bought via ration cards issued to state workers with the implicit threat that both job and card are at risk if they vote against the government. Meanwhile, the country’s highest profile opposition leaders are barred from running, in exile, or under arrest.

- ↑ "The Latest: Venezuela Opposition Calls Election a 'Farce'". U.S. News & World Report. Associated Press. 21 May 2018. Archived from the original on 21 May 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ↑ Corrales, Javier; Penfold, Michael (2014). Dragon in the tropics : Hugo Chavez and the political economy of revolution in Venezuela (Second ed.). [S.l.]: Brookings Institution Press. p. xii. ISBN 0815725930.

- ↑ Corrales, Javier. "Venezuela's Odd Transition to Dictatorship". Americas Quarterly. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ↑ Brodzinsky, Sibylla (21 October 2016). "Venezuelans warn of 'dictatorship' after officials block bid to recall Maduro". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ↑ "Almagro: Maduro se transforma en dictador por negarles a venezolanos derecho a decidir su futuro". CNN en Español. 24 August 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Treasury Sanctions the President of Venezuela". United States Department of the Treasury. 31 July 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Perfil | ¿Quién es Nicolás Maduro?". El Mundo (in Spanish). 27 December 2012. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Profile: Nicolas Maduro – Americas". Al Jazeera. March 2013. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ↑ Lamb, Peter (17 December 2015). Historical Dictionary of Socialism. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 289. ISBN 978-1-442-25827-3.

- ↑ Turner, Barry (2013). The Statesman's Yearbook 2014: The Politics, Cultures and Economies of the World. Springer. p. 1486. ISBN 978-1-349-59643-0.

- 1 2 3 Oropeza, Valentina (15 April 2013). "Perfil de Nicolás Maduro: El 'delfín' que conducirá la revolución bolivariana". El Tiempo (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2016-03-06.

- ↑ Neuman, William (22 December 2012). "Waiting to See if a 'Yes Man' Picked to Succeed Chávez Might Say Something Else". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ↑ Maduro: Rectifique presidente Obama, somos mestizos. 10 February 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2016 – via YouTube.

- ↑ "Venezuela's 'anti-Semitic' leader admits Jewish ancestry".

- 1 2 3 4 Lopez, Virginia; Watts, Jonathan (15 April 2013). "Who is Nicolás Maduro? Profile of Venezuela's new president". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- 1 2 "MinCI – Maduro: perfecto heredero de Chávez". MinCI. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ "Venezuela's Chavez Says Cancer Back, Plans Surgery". USA Today. 27 August 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ↑ Fermín, Daniel (12 January 2015). "La boleta de clase del hijo de Maduro". El Estímulo. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Venezuelan president's son, Nicolas Maduro Jr., showered in dollar bills as economy collapses". Fox News Latino. 19 March 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ↑ Cawthorne, Andrew; Naranjo, Mario (9 December 2012). "Who is Nicolas Maduro, Possible Successor to Hugo Chávez?". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ↑ Dreier, Hannah (12 November 2015). "US Court: Nephews of Venezuela First Lady Held Without Bail". Associated Press. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ↑ Guererro, Kay; Dominguez, Claudia; Shoichet, Catherine E. (12 November 2015). "Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro's family members indicted in U.S. court". CNN. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ↑ Meza, Alfredo (22 November 2015). "La generosa tía Cilia". El País. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- 1 2 Lopez, Virginia (13 December 2012). "Nicolás Maduro: Hugo Chávez's incendiary heir". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ↑ Peñaloza, Carlos (2014). Chávez, el delfin de Fidel: la historia secreta del golpe del 4 de febrero. Miami: Alexandria Library. p. 184. ISBN 1505750334. OCLC 904959157.

Among the escorts of Fidel who entered the country that night who entered camouflaged as Cuban, without being identified, Nicolás Maduro, the young man who was sought after for the kidnapping of William Niehaus since 1979.

- ↑ Vitello, Paul (22 October 2013). "William Niehous survived three years in captivity in Venezuela". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2018-03-14.

- ↑ "Nicolás Maduro a la cabeza de la revolución" Archived 29 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine. (in Spanish). Últimas Noticias. 9 December 2012.

- ↑ Peñaloza, Carlos (2014). Chávez, el delfin de Fidel : la historia secreta del golpe del 4 de febrero. Miami: Alexandria Library. p. 184. ISBN 1505750334. OCLC 904959157.

Maduro had gone through a long process of formation in Cuba under the protection of Pedro Miret, the powerful Cuban commander and man very close to Fidel.

- ↑ Peñaloza, Carlos (2014). Chávez, el delfin de Fidel : la historia secreta del golpe del 4 de febrero. Miami: Alexandria Library. p. 184. ISBN 1505750334. OCLC 904959157.

... Maduro returned to Venezuela with the permission to approach Chávez acting as a mole of the G2.

- ↑ Carroll, Rory (2013). "5: Survival of the fittest". Comandante: Inside Hugo Chávez's Venezuela. Penguin Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-59420-457-9. LCCN 2012039514.

- 1 2 Shoichet, Catherine E. (9 December 2012). "Venezuela: As Chavez Battles Cancer, Maduro Waits in the Wings". CNN.

- ↑ "Publicista brasileña revela que en 2011 ya se sabía que Maduro sería el sucesor de Chávez". Diario Las Americas (in Spanish). 15 May 2017. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- ↑ James, Ian (8 December 2012). "Venezuela's Chavez Says Cancer Back, Plans Surgery". USA Today. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ↑ Crooks, Nathan (8 December 2012). "Venezuela's Chavez Says New Cancer Cells Detected in Cuba Exams". Bloomberg. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ↑ "Profile: Nicolas Maduro". BBC News. 13 December 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ↑ Shoichet, Catherine E.; Ford, Dana (5 March 2013). "Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez dies". CNN.

- ↑ CBS/AP (6 March 2013). "Hugo Chavez's handpicked successor at helm in Venezuela, for time being". CBS News.

- ↑ "Constitution of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela" Archived 21 August 2011 at WebCite.

- ↑ "Venezuela's foreign minister says VP Maduro is interim president". Fox News Channel. 5 March 2013.

- ↑ Carroll, Rory; Lopez, Virginia (9 March 2013). "Venezuelan opposition challenges Nicolás Maduro's legitimacy". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ "Constitución de la República de Venezuela" (in Spanish).

- ↑ "Maduro convoca a elecciones inmediatas – Pim pom papas noticias". Noticias.pimpompapas.com. 8 March 2013. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- ↑ "Presidente Maduro: Asumo está banda de Chávez para cumplir el juramento de continuar la Revolución (+Fotos+Video) – Venezolana de Televisión". Vtv.gob.ve (in Spanish). VTV. 8 March 2013. Archived from the original on 17 January 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- ↑ Corrales, Javier; Penfold, Michael (2 April 2015). Dragon in the Tropics: The Legacy of Hugo Chávez. Brookings Institution Press. p. 13. ISBN 0815725930.

- ↑ Shoichet, Catherine (15 April 2013). "Chavez's Political Heir Declared Winner; Opponent Demands Recount". CNN. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ↑ Kroth, Olivia (18 April 2013). "Delegations from 15 countries to assist Maduro's inauguration in Venezuela". Pravda.ru. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ↑ "Venezuela Fights Shortage Blues With New Happiness Agency". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 27 October 2013.

- ↑ "Venezuela starts validating recall referendum signatures". BBC. 21 June 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ↑ Kurmanaev, Anatoly (6 July 2016). "Venezuela Detains Activists Calling for Maduro's Ouster". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ↑ Sibylla Brodzinsky (27 July 2016). "Venezuela government stalling recall vote to keep power, opposition claims". The Guardian.

- ↑ Cawthorne, Andrew (1 August 2016). "Venezuela election board okays opposition recall push first phase". Reuters. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ↑ "La lista de los 40 países democráticos que hasta el momento desconocieron la Asamblea Constituyente de Venezuela". Infobae (in Spanish). 31 July 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ↑ "Fear spreads in Venezuela ahead of planned protest of controversial election". The Washington Post. 28 July 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- ↑ Virginia López and Sibylla Brodzinsky (July 25, 2017). "Venezuela to vote amid crisis: all you need to know". The Guardian. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- ↑ "Venezuela's embattled socialist president calls for citizens congress, new constitution". USA TODAY. Associated Press. 1 May 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ↑ "What are Venezuelans voting for and why is it so divisive?". BBC News. 30 July 2017. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- ↑ "¿Qué busca Nicolás Maduro con el nuevo autogolpe que quiere imponer en Venezuela?" [What is Maduro seeking with the new self-coup that he tries to impose in Venezuela?] (in Spanish). La Nación. May 2, 2017. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- ↑ Kraul, Chris (17 May 2017). "Human rights activists say many Venezuelan protesters face abusive government treatment". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- ↑ "Gobierno extiende por décima vez el decreto de emergencia económica". La Patilla (in Spanish). 18 July 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ "Maduro niega la diáspora venezolana en la ONU: Se ha fabricado por distintas vías una crisis migratoria - LaPatilla.com". LaPatilla.com (in Spanish). 2018-09-26. Retrieved 2018-09-27.

- ↑ Porzucki, Nina (13 January 2016). "It's not Hugo Chavez's Venezuela anymore, or is it?". Public Radio International. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ↑ "Venezuela's Collapse". Bloomberg. 2018-05-14. Retrieved 2018-05-22.

- 1 2 "Marsh Political Risk Map | 2017". Marsh. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ↑ "What's behind Venezuela's crippling crisis, and why it matters to the U.S." NBC News. 8 May 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ↑ "Maduro: El Plan de la Patria 2025 debe estar orientado a construir el socialismo". La Patilla (in Spanish). 2018-10-11. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- 1 2 "Venezuela launches massive street security operation". BBC News. 13 May 2013.

- ↑ "Venezuelan Anti-Crime Program Records 55% Homicide Reduction". Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ "Safe Homeland plan reduced murder by 55% in Caracas parish". AVN. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ Carmen Melendez (1 November 2014). "Relanzado Plan Patria Segura este sábado en todo el territorio nacional (+Fotos)". Venezolana de Television. Archived from the original on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela Ranks World's Second In Homicides: Report". NBC News. 29 December 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ "Venezuela's economy: Medieval policies". The Economist. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela's April inflation jumps to 5.7 percent: report". Reuters. 17 May 2014. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela's black market rate for US dollars just jumped by almost 40%". Quartz (publication). 26 March 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ↑ Kevin Voigt (6 March 2013). "Chavez leaves Venezuelan economy more equal, less stable". CNN. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ↑ Corrales, Javier (7 March 2013). "The House That Chavez Built". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ↑ Siegel, Robert (25 December 2014). "For Venezuela, Drop In Global Oil Prices Could Be Catastrophic". NPR. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ "Mr. Maduro in His Labyrinth". The New York Times. 26 January 2015. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ↑ "Venezuela's government seizes electronic goods shops". BBC. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ↑ "Maduro anuncia que el martes arranca nueva "ofensiva económica"". La Patilla. 22 April 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ↑ "Maduro insiste con una nueva "ofensiva económica"". La Nacion. 23 April 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ↑ "Decree powers widen Venezuelan president's economic war". CNN. 20 November 2013. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ↑ Yapur, Nicolle (24 April 2014). "Primera ofensiva económica trajo más inflación y escasez". El Nacional. Archived from the original on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ↑ Gupta, Girish (3 November 2014). "Could Low Oil Prices End Venezuela's Revolution?". The New Yorker. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ↑ "New Year's Wishes for Venezuela". The Washington Post. Bloomberg. 2 January 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ Hanke, John H. "Measuring Misery around the World". The Cato Institute. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ↑ "Amid Rationing, Venezuela Takes The Misery Crown". Investors Business Daily. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ↑ Anderson, Elizabeth (3 March 2015). "Which are the 15 most miserable countries in the world?". The Telegraph. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ↑ Saraiva, A Catarina; Jamrisko, Michelle; Fonseca Tartar, Andre (2 March 2015). "The 15 Most Miserable Economies in the World". Bloomberg. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ↑ "The World's Most – And Least – Miserable Countries in 2016 – Zero Hedge". www.zerohedge.com. 7 January 2013.

- ↑ Pons, Corina; Cawthorne, Andrew (30 December 2014). "Recession-hit Venezuela vows New Year reforms, foes scoff". Reuters.

- 1 2 Kurmanaev, Anatoly (12 July 2016). "Venezuelan President Puts Armed Forces in Charge of New Food Supply System". Dow Jones & Company, Inc. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ↑ "Maduro prometió que Venezuela será una potencia en 2050". El Nacional (in Spanish). 2018-07-08. Retrieved 2018-07-10.

- ↑ "Venezuela Military Seizes Major Ports as Economic Crisis Deepens". Voice of America. 13 July 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Martín, Sabrina (13 July 2016). "Venezuela: Maduro Hands over Power to Defense Minister". PanAm Post. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- 1 2 Camacho, Carlos (12 July 2016). "Defense Minister Becomes 2nd Most Powerful Man in Venezuela". Latin American Herald Tribune. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- 1 2 "Venezuela Gets a New Comandante". Bloomberg News. 19 July 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ↑ "Maduro blames US for violence over Venezuela vote". Associated Press. 16 April 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- 1 2 Otis, John (8 March 2015). "Venezuela's President Sees Only Plots As His Economy Crumbles". NPR. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- 1 2 Mogollon, Mery; Kraul, Chris (5 March 2015). "Venezuela commemorates Hugo Chavez amid economic and other woes". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "Seven Venezuelan officials targeted by US". BBC. 10 March 2015.

- ↑ "Venezuela launches anti-American, in-your-face propaganda campaign in the U.S." Fox News Latino. 18 March 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ↑ "Venezuela lashes U.S., opposition amid blame over activist's slaying". Reuters. 27 November 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ↑ Vyas, Kejal. "Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro Says He Will Sue U.S." The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ↑ "Expresidentes iberoamericanos piden cambios en Venezuela". Panamá América. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tegel, Simeon (2 April 2015). "Venezuela's Maduro is racing to collect 10 million signatures against Obama". GlobalPost. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ↑ "Trabajadores petroleros que no firmen contra el decreto Obama serán despedidos". Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ "Despiden a dos trabajadores de Corpozulia por negarse a firmar contra decreto Obama". Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ "Confirman despido de dos trabajadores de Corpozulia por no firmar contra decreto Obama". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ "Diario El Vistazo". Diario El Vistazo. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ Sabrina Martín. "Bajo amenazas, chavismo recolecta firmas contra Obama en Venezuela". PanAm Post. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ "MCM: Declaración de Panamá es un hito histórico en la lucha por la democracia en Venezuela". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ "25 expresidentes iberoamericanos firmaron Declaración de Panamá". El Mundo Economía y Negocios. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- 1 2 3 Rey Mallén, Patiricia (15 April 2014). "China's Paying Venezuela To Stay Afloat. Now Maduro Wants To Be Friends". International Business Times. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ↑ "Chinese systems get 'combat experience' in Venezuela". IHS Jane's. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela will buy 300 new anti-riot vehicles". Army Recognition. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ↑ Delgado, Antonio María (20 March 2014). "Estudio concluye que Maduro nació en Bogotá". El Nuevo Herald. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ↑ "Afirman tener pruebas de que Maduro es colombiano". Noticias RCN. 29 July 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "TSJ contradice a Maduro y resuelve el misterio de su nacionalidad". El Nacional. 28 October 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ↑ "Machado: Ya van 4 parroquias donde nació Nicolás Maduro". Informe21. 10 October 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ↑ "Vielma Mora dijo el 2 de abril: Nicolas Maduro nació en El Palotal, San Antonio del Táchira". Diario del Pueblo. Noticiero Digital. 18 June 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ↑ "EN VIDEO: Los cuatro lugares de nacimiento de Nicolás Maduro ¡Escoja su favorito!". Maduradas. 31 December 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ↑ Pineda Sleinan, Julett (29 October 2016). "El Valle, San Pedro o La Candelaria, ¿dónde nació el presidente Maduro?". Efecto Cocuyo. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ↑ "¿Maduro es colombiano?: polémica llega al parlamento venezolano". El Tiempo. 30 January 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- 1 2 "¿Dónde nació Nicolás Maduro?". Diario Las Américas. 5 March 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- 1 2 3 Peñaloza, Pedro Pablo (29 October 2016). "¿Dónde nació Nicolás Maduro? El Supremo de Venezuela contradice la autobiografía del mandatario". Univisión Noticias. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ↑ Delgado, Antonio María (18 March 2018). "Según Pastrana, nuevo documento prueba irrevocablemente la nacionalidad colombiana de Maduro". El Nuevo Herald. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ↑ "TSJ en el exilio decreta nulidad de elección de Maduro como presidente". Diario las Américas. 11 January 2018. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- 1 2 3 Dreir, Hannah (23 July 2014). "Venezuelan Conspiracy Theories a Threat to Critics". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lansberg-Rodríguez, Daniel (15 March 2015). "Coup Fatigue in Caracas". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ↑ "Nicolas Maduro recebeu 13 milhões de ataques psicológicos – lainfo.es". Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ "Maduro dice que telenovelas generan delincuencia". Informe21.com. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- 1 2 Wallis, Daniel; Buitrago, Deisy (23 January 2013). "Venezuela's vice president says he's target of assassination plot". Reuters. Retrieved 27 August 2014.

- ↑ Esteban Rojas (May 6, 2017). "La guerra informativa invade las redes" [The informative war invades the networks]. La Nación (in Spanish). Retrieved May 8, 2017.

- ↑ Lee, Brianna (25 March 2015). "Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro's Approval Rating Gets A Tiny Bump Amid Tensions With US". International Business Times. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ↑ "Woman who hit Venezuelan president with mango given new home". Special Broadcasting Service. 25 April 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ↑ "Letter of the OAS Secretary General to the President of Venezuela". Organization of American States. 12 January 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ↑ "Venezuela: OAS Should Invoke Democratic Charter". Human Rights Watch. 16 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ↑ "The Inter-American Democratic Charter and Mr. Insulza". Human Rights Foundation. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ↑ Ordonez, Franco (4 May 2016). "Venezuela calls for extraordinary OAS meeting". The Miami Herald. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ↑ Ordonez, Franco (5 May 2016). "Venezuela accuses U.S. of conspiring to topple Nicolás Maduro". The Kansas City Star. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ↑ "Maduro sobre Almagro: 'Es un traidor, algún día contaré su historia'". Noticias24. 17 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ↑ "Message from the OAS Secretary General to the President of Venezuela". Organization of American States. 18 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ↑ "Sepa quiénes son los 11 venezolanos señalados por la OEA por supuestos crímenes de lesa humanidad - Efecto Cocuyo". Efecto Cocuyo (in Spanish). 2018-05-30. Retrieved 2018-05-31.

- ↑ Smith, Marie-Danielle (2018-05-30). "Canada introduces new sanctions on Venezuelan regime in wake of devastating report on crimes against humanity". National Post. Retrieved 2018-05-31.

- ↑ "TSJ en el exilio sentenció a Nicolás Maduro a 18 años y 3 meses de cárcel por corrupción - LaPatilla.com". La Patilla (in Spanish). 2018-08-15. Retrieved 2018-08-16.

- ↑ "Almagro solicita al presidente de la AN que acate la sentencia emitida por el TSJ en el exilio contra Maduro (Carta)". La Patilla (in Spanish). 2018-08-20. Retrieved 2018-08-21.

- 1 2 Yagoub, Mimi. "Venezuela Military Officials Piloted Drug Plane". InSight Crime. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- 1 2 Blasco, Emili J. (19 November 2015). "La Casa Militar de Maduro custodió el traslado de droga de sus sobrinos". ABC. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ↑ Raymond, Nate (19 November 2016). "Venezuelan first lady's nephews convicted in U.S. drug trial". Reuters. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ↑ "Narcosobrinos Archivo". La Patilla. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ↑ "EEUU: postergaron una vez más la audiencia de los narcosobrinos de Maduro | Nicolás Maduro, Narcotráfico en Venezuela, Nueva York – América". Infobae. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ↑ "Restan días para el juicio de los "narcosobrinos"". Venezuela al Día. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ↑ Carrillo Mazzali, Jessica. "Difieren audiencia del caso de los "narcosobrinos" de Cilia". Tal Cual. Archived from the original on 2 May 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ↑ "La mujer de Maduro acusa a la DEA de secuestrar a sus "narcosobrinos"". ABC (in Spanish). Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ↑ Lozano, Daniel. "Nicolás Maduro, seis días de silencio en torno al escándalo de los 'narcosobrinos'". El Mundo. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ↑ "Nephews of Venezuela's first lady sentenced to prison for cocaine plot". The Guardian. 14 December 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ "What's Wrong with Venezuela?". International Policy Digest. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ↑ "U.S. arrests Nicolas Maduro's family members". CNN. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ↑ Kurmanaev, Anatoly. "Arrest of Nicolas Maduro Relatives a 'Kidnapping,' Venezuelan Official Says". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ↑ Sallah, Michael; Delgado, Antonio (26 December 2015). "Bal Harbour to Caracas: Millions in drug money". The Miami Herald. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ↑ Sallah, Michael (28 December 2015). "Bank denies report that Maduro aide was sent drug money". The Miami Herald. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ↑ "Denuncian en Panamá a Maduro y a su esposa por posible blanqueo de dólares". El Nuevo Herald. 4 January 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ↑ "Treasury Targets Influential Former Venezuelan Official and His Corruption Network". Office of Foreign Assets Control. United States Department of the Treasury. 18 May 2018. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ↑ "Canciller Maduro llama "sifrinitos" y "fascistas" a dirigentes opositores". El Universal. 12 April 2012. Archived from the original on 2 July 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ↑ Avery, Dan (13 April 2012). "Hugo Chavez's Foreign Minister Calls Opposition Party "Little Faggots"". Queerty. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- 1 2 "Nicolás Maduro utiliza la homofobia para captar votos". Espiritu Gay. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ "Venezuela Says U.S. Plans To Kill Capriles, Maduro Accused Of Homophobic Slur". HuffPost. 13 March 2013. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ↑ "Reuters: controversia sobre la sexualidad toma protagonismo en la carrera electoral de Venezuela". Noticias24. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ "La "tremenda grosería" que se le salió a Maduro en plena cadena nacional". Archived from the original on 14 May 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ "Maduro a Congreso de España: "Vayan a opinar de su madre"". LARED21. 15 April 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ "Maduro podría ser dueño de empresa méxicana distribuidora de los CLAP". El Nacional (in Spanish). 23 August 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ↑ Wyss, Jim (23 August 2017). "Venezuela's ex-prosecutor Luisa Ortega accuses Maduro of profiting from nation's hunger". Miami Herald. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ↑ Prengaman, Peter (23 August 2017). "Venezuela's ousted prosecutor accuses Maduro of corruption". Associated Press. ABC News. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- 1 2 3 "De banquete en banquete: Los "rojitos" que no escatiman a la hora de comer pese a la crisis". El Cooperante (in Spanish). 2018-09-22. Retrieved 2018-09-24.

- ↑ Hayes, Christal (3 November 2017). "Venezuelan President Eats Empanada on Live TV While Addressing Starving Nation". Newsweek. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ↑ "Venezuelan Dictator Caught Scarfing Down Empanada During Live TV Address While His People Starve". Slate. 3 November 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ↑ "As his people starve, Venezuelan President munches on empanada while addressing the nation on live TV". Newsweek. 2017-11-03. Retrieved 2018-05-27.

- ↑ "Venezuelan President Maduro is caught eating empanada during speech". Mail Online. Retrieved 2018-05-27.

- ↑ Editorial, Reuters. "Venezuelans outraged by Maduro's steak feast at Salt Bae restaurant". Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ↑ "El hijo de Nicolás Maduro bailó bajo una lluvia de dólares en una fiesta". La Nación. 18 March 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ↑ "Polémica por un video del hijo de Maduro en el que baila entre billetes". Infobae. 17 March 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- 1 2 "Hijo de Maduro baila bajo lluvia de billetes". La Razón. 16 March 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ↑ "En video: el hijo de Nicolás Maduro baila en una 'lluvia' de billetes". El Tiempo. 17 March 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ↑ "Como el hijo de Maduro: Otros escándalos del chavismo". El Comercio. 17 March 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ↑ "Hijo de Nicolás Maduro baila en boda mientras le lanzan billetes". El Universo. 18 March 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- 1 2 "Ousted Venezuelan prosecutor leaks Odebrecht bribe video". Washington Post. 12 October 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- ↑ "Américo Mata habría recibido pagos de Odebrecht para campaña de Maduro | El Cooperante". El Cooperante (in Spanish). 25 August 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ↑ "Venezuela sanctions". Government of Canada. 22 September 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ↑ "Canada sanctions 40 Venezuelans with links to political, economic crisis". The Globe and Mail. 22 September 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2017.