Neoliberalism

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Economic liberalism |

|---|

|

|

Origins |

|

Ideas

|

|

Neoliberalism or neo-liberalism[1] refers primarily to the 20th-century resurgence of 19th-century ideas associated with laissez-faire economic liberalism.[2]:7 Those ideas include economic liberalization policies such as privatization, austerity, deregulation, free trade[3] and reductions in government spending in order to increase the role of the private sector in the economy and society.[11] These market-based ideas and the policies they inspired constitute a paradigm shift away from the post-war Keynesian consensus which lasted from 1945 to 1980.[12][13]

English-speakers have used the term "neoliberalism" since the start of the 20th century with different meanings,[14] but it became more prevalent in its current meaning in the 1970s and 1980s, used by scholars in a wide variety of social sciences[15][16] as well as by critics.[17][18] Modern advocates of free market policies avoid the term "neoliberal"[19] and some scholars have described the term as meaning different things to different people[20][21] as neoliberalism "mutated" into geopolitically distinct hybrids as it travelled around the world.[4] As such, neoliberalism shares many attributes with other concepts that have contested meanings, including democracy.[22]

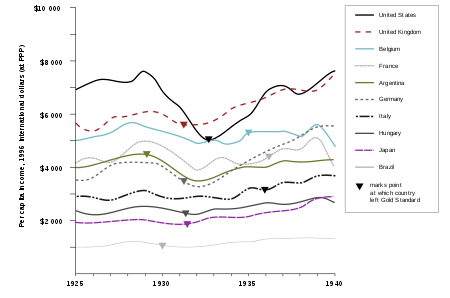

The definition and usage of the term have changed over time.[5] As an economic philosophy, neoliberalism emerged among European liberal scholars in the 1930s as they attempted to trace a so-called "third" or "middle" way between the conflicting philosophies of classical liberalism and socialist planning.[23]:14–15 The impetus for this development arose from a desire to avoid repeating the economic failures of the early 1930s, which neoliberals mostly blamed on the economic policy of classical liberalism. In the decades that followed, the use of the term "neoliberal" tended to refer to theories which diverged from the more laissez-faire doctrine of classical liberalism and which promoted instead a market economy under the guidance and rules of a strong state, a model which came to be known as the social market economy.

In the 1960s, usage of the term "neoliberal" heavily declined. When the term re-appeared in the 1980s in connection with Augusto Pinochet's economic reforms in Chile, the usage of the term had shifted. It had not only become a term with negative connotations employed principally by critics of market reform, but it also had shifted in meaning from a moderate form of liberalism to a more radical and laissez-faire capitalist set of ideas. Scholars now tended to associate it with the theories of Mont Pelerin Society economists Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman and James M. Buchanan, along with politicians and policy-makers such as Margaret Thatcher, Ronald Reagan and Alan Greenspan.[5][24] Once the new meaning of neoliberalism became established as a common usage among Spanish-speaking scholars, it diffused into the English-language study of political economy.[5] By 1994, with the passage of NAFTA and with the Zapatistas' reaction to this development in Chiapas, the term entered global circulation.[4] Scholarship on the phenomenon of neoliberalism has been growing over the last couple of decades.[16] The impact of the global 2008–2009 crisis has also given rise to new scholarship that criticizes neoliberalism and seeks policy alternatives.[25]

Terminology

Origins

An early use of the term in English was in 1898 by the French economist Charles Gide to describe the economic beliefs of the Italian economist Maffeo Pantaleoni,[26] with the term "néo-libéralisme" previously existing in French,[14] and the term was later used by others including the classical liberal economist Milton Friedman in a 1951 essay.[27] In 1938 at the Colloque Walter Lippmann, the term "neoliberalism" was proposed, among other terms, and ultimately chosen to be used to describe a certain set of economic beliefs.[23]:12–13[28] The colloquium defined the concept of neoliberalism as involving "the priority of the price mechanism, free enterprise, the system of competition, and a strong and impartial state".[23]:13–14 To be "neoliberal" meant advocating a modern economic policy with state intervention.[23]:48 Neoliberal state interventionism brought a clash with the opposing laissez-faire camp of classical liberals, like Ludwig von Mises.[29] Most scholars in the 1950s and 1960s understood neoliberalism as referring to the social market economy and its principal economic theorists such as Eucken, Röpke, Rüstow and Müller-Armack. Although Hayek had intellectual ties to the German neoliberals, his name was only occasionally mentioned in conjunction with neoliberalism during this period due to his more pro-free market stance.[30]

During the military rule under Augusto Pinochet (1973–1990) in Chile, opposition scholars took up the expression to describe the economic reforms implemented there and its proponents (the "Chicago Boys").[5] Once this new meaning was established among Spanish-speaking scholars, it diffused into the English-language study of political economy.[5] According to one study of 148 scholarly articles, neoliberalism is almost never defined but used in several senses to describe ideology, economic theory, development theory, or economic reform policy. It has largely become a term of condemnation employed by critics and suggests a market fundamentalism closer to the laissez-faire principles of the paleoliberals than to the ideas of those who originally attended the colloquium. This leaves some controversy as to the precise meaning of the term and its usefulness as a descriptor in the social sciences, especially as the number of different kinds of market economies have proliferated in recent years.[5]

Another center-left movement from modern American liberalism that used the term "neoliberalism" to describe its ideology formed in the United States in the 1970s. According to David Brooks, prominent neoliberal politicians included Al Gore and Bill Clinton of the Democratic Party of the United States.[31] The neoliberals coalesced around two magazines, The New Republic and the Washington Monthly.[32] The "godfather" of this version of neoliberalism was the journalist Charles Peters,[33] who in 1983 published "A Neoliberal's Manifesto".[34]

Current usage

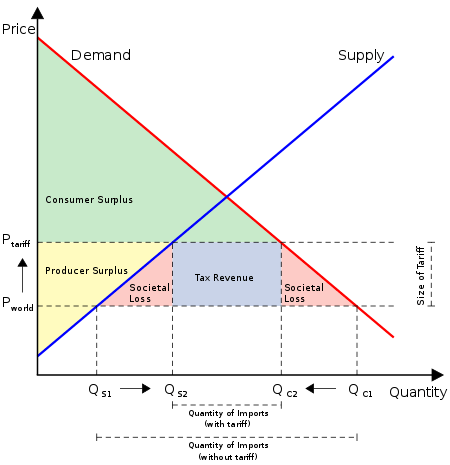

Elizabeth Shermer argued that the term gained popularity largely among left-leaning academics in the 1970s "to describe and decry a late twentieth-century effort by policy makers, think-tank experts, and industrialists to condemn social-democratic reforms and unapologetically implement free-market policies".[35] Neoliberal theory argues that a free market will allow efficiency, economic growth, income distribution, and technological progress to occur. Any state intervention to encourage these phenomena will worsen economic performance.[36]

The Handbook of Neoliberalism[4]

According to some scholars, neoliberalism is commonly used as a catchphrase and pejorative term, outpacing similar terms such as monetarism, neoconservatism, the Washington Consensus and "market reform" in much scholarly writing,[5] The term has been criticized,[37][38] particularly by those who often advocate for policies characterized as neoliberal.[39]:74 Historian Daniel Stedman Jones says the term "is too often used as a catch-all shorthand for the horrors associated with globalization and recurring financial crises".[40]:2 The Handbook of Neoliberalism posits that the term has "become a means of identifying a seemingly ubiquitous set of market-oriented policies as being largely responsible for a wide range of social, political, ecological and economic problems". Yet the handbook argues to view the term as merely a pejorative or "radical political slogan" is to "reduce its capacity as an analytic frame. If neoliberalism is to serve as a way of understanding the transformation of society over the last few decades then the concept is in need of unpacking".[4] Currently, neoliberalism is most commonly used to refer to market-oriented reform policies such as "eliminating price controls, deregulating capital markets, lowering trade barriers" and reducing state influence on the economy, especially through privatization and austerity.[5] Other scholars note that neoliberalism is associated with the economic policies introduced by Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom and Ronald Reagan in the United States.[6]

There are several distinct usages of the term that can be identified:

- As a development model, it refers to the rejection of structuralist economics in favor of the Washington Consensus.

- As an ideology, it denotes a conception of freedom as an overarching social value associated with reducing state functions to those of a minimal state.

Sociologists Fred L. Block and Margaret R. Somers claim there is a dispute over what to call the influence of free market ideas which have been used to justify the retrenchment of New Deal programs and policies over the last thirty years: neoliberalism, laissez-faire or "free market ideology".[41] Others such as Susan Braedley and Med Luxton assert that neoliberalism is a political philosophy which seeks to "liberate" the processes of capital accumulation.[42] In contrast, Frances Fox Piven sees neoliberalism as essentially hyper-capitalism.[43] However, Robert W. McChesney, while defining it as "capitalism with the gloves off", goes on to assert that the term is largely unknown by the general public, particularly in the United States.[44]:7–8 Lester Spence uses the term to critique trends in Black politics, defining neoliberalism as "the general idea that society works best when the people and the institutions within it work or are shaped to work according to market principles".[45] According to Philip Mirowski, neoliberalism views the market as the greatest information processor superior to any human being. It is hence considered as the arbiter of truth. Neoliberalism is distinct from liberalism insofar as it does not advocate laissez-faire economic policy but instead is highly constructivist and advocates a strong state to bring about market-like reforms in every aspect of society.[46]

Early history

Colloque Walter Lippmann

The worldwide Great Depression of the 1930s brought about high unemployment and widespread poverty and was widely regarded as a failure of economic liberalism. To renew liberalism, a group of 25 intellectuals organised the Walter Lippmann Colloquium at Paris in August 1938. It brought together Louis Rougier, Walter Lippmann, Friedrich von Hayek, Ludwig von Mises, Wilhelm Röpke and Alexander Rüstow among others. Most agreed that the liberalism of laissez-faire had failed and that a new liberalism needed to take its place with a major role for the state. Mises and Hayek refused to condemn laissez-faire, but all participants were united in their call for a new project they dubbed "neoliberalism".[48]:18–19 They agreed to develop the Colloquium into a permanent think tank called Centre International d’Études pour la Rénovation du Libéralisme based in Paris.

Deep disagreements in the group separated "true (third way) neoliberals" around Rüstow and Lippmann on the one hand and old school liberals around Mises and Hayek on the other. The first group wanted a strong state to supervise, while the second insisted that the only legitimate role for the state was to abolish barriers to market entry. Rüstow wrote that Hayek and Mises were relics of the liberalism that caused the Great Depression. Mises denounced the other faction, complaining that ordoliberalism really meant "ordo-interventionism".[48]:19–20

Mont Pelerin Society

Neoliberalism began accelerating in importance with the establishment of the Mont Pelerin Society in 1947, whose founding members included Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman, Karl Popper, George Stigler and Ludwig von Mises. The Colloque Walter Lippmann was largely forgotten.[49] The new society brought together the widely scattered free market thinkers and political figures.

Hayek and others believed that classical liberalism had failed because of crippling conceptual flaws and that the only way to diagnose and rectify them was to withdraw into an intensive discussion group of similarly minded intellectuals.[23]:16

With central planning in the ascendancy worldwide and few avenues to influence policymakers, the society served to bring together isolated advocates of liberalism as a "rallying point" – as Milton Friedman phrased it. Meeting annually, it would soon be a "kind of international 'who's who' of the classical liberal and neo-liberal intellectuals."[50] While the first conference in 1947 was almost half American, the Europeans dominated by 1951. Europe would remain the epicenter of the community with Europeans dominating the leadership.[23]:16–17

Post-World War II neo-liberal currents

Argentina

In the 1960s, Latin American intellectuals began to notice the ideas of ordoliberalism; these intellectuals often used the Spanish term "neoliberalismo" to refer to this school of thought. They were particularly impressed by the social market economy and the Wirtschaftswunder ("economic miracle") in Germany and speculated about the possibility of accomplishing similar policies in their own countries. Neoliberalism in 1960s meant essentially a philosophy that was more moderate than classical liberalism and favored using state policy to temper social inequality and counter a tendency toward monopoly.[5]

In 1976, the military dictatorship's economic plan led by Martínez de Hoz was the first attempt at a neoliberalist plan in Argentina. They implemented a fiscal austerity plan, whose goal was to reduce money printing and thus inflation. In order to achieve this, salaries were frozen, but they were unable to reduce inflation, which led to a drop in the real salary of the working class. Aiming for a free market, they also decided to open the country's borders, so that foreign goods could freely enter the country. Argentina's industry, which had been on the rise for the last 20 years since Frondizi's economic plan, rapidly declined, because it wasn't able to compete with foreign goods. Finally, the deregulation of the financial sector, gave a short-term growth, but then rapidly fell apart when capital fled to the United States in the Reagan years. Following the measures, there was an increase in poverty from 9% in 1975 to 40% at the end of 1982.[51]

From 1989 to 2001, another neoliberalist plan was attempted by Domingo Cavallo. This time, the privatization of public services was the main objective of the government; although financial deregulation and open borders to foreign goods were also re-implemented. While some privatizations were welcomed, the majority of them were criticized for not being in the people's best interests. Along with an increased labour market flexibility, the final result of this plan was an unemployment rate of 25% and 60% of people living under the poverty line, alongside 33 people killed by the police in protests that ended up with the president, Fernando de la Rúa, resigning two years before his term as president was completed.

Australia

In Australia, neoliberal economic policies (known at the time as "economic rationalism"[52] or "economic fundamentalism") were embraced by governments of both the Labor Party and the Liberal Party since the 1980s. The Labor governments of Bob Hawke and Paul Keating from 1983 to 1996 pursued economic liberalisation and a program of micro-economic reform. These governments privatized government corporations, deregulated factor markets, floated the Australian dollar and reduced trade protection.[53]

Keating, as federal treasurer, implemented a compulsory superannuation guarantee system in 1992 to increase national savings and reduce future government liability for old age pensions.[54] The financing of universities was deregulated, requiring students to contribute to university fees through a repayable loan system known as the Higher Education Contribution Scheme (HECS) and encouraging universities to increase income by admitting full-fee-paying students, including foreign students.[55] The admitting of domestic full fee paying students to public universities was stopped in 2009 by the Rudd Labor government.[56]

Immigration to the mainland capitals by conflict-migrants had seen capital flows follow soon after, such as from war torn Lebanon and Vietnam. Latter economic-migrants from mainland China also, up to recent restrictions, had invested significantly in the property markets.

Chile

In 1955, a select group of Chilean students (later known as the Chicago Boys) were invited to the University of Chicago to pursue postgraduate studies in economics. They worked directly under Friedman and his disciple, Arnold Harberger, while also being exposed to Hayek. When they returned to Chile in the 1960s, they began a concerted effort to spread the philosophy and policy recommendations of the Chicago and Austrian schools, setting up think tanks and publishing in ideologically sympathetic media. Under the military dictatorship headed by Pinochet and severe social repression, the Chicago boys implemented radical economic reform. The latter half of the 1970s witnessed rapid and extensive privatization, deregulation and reductions in trade barriers. In 1978, policies that would reduce the role of the state and infuse competition and individualism into areas such as labor relations, pensions, health and education were introduced.[5] These policies resulted in widening inequality as they negatively impacted the wages, benefits and working conditions of Chile's working class.[51][59] According to Chilean economist Alejandro Foxley, by the end of Pinochet's reign around 44% of Chilean families were living below the poverty line.[60] According to Klien, by the late 1980s the economy had stabilized and was growing, but around 45% of the population had fallen into poverty while the wealthiest 10% saw their incomes rise by 83%.[61]

In 1990, the military dictatorship ended. Hayek argued that increased economic freedom had put pressure on the dictatorship over time and increased political freedom. Years earlier, he argued that "economic control is not merely control of a sector of human life which can be separated from the rest; it is the control of the means for all our ends".[62] The Chilean scholars Martínez and Díaz rejected this argument, pointing to the long tradition of democracy in Chile. The return of democracy required the defeat of the Pinochet regime, though it had been fundamental in saving capitalism. The essential contribution came from profound mass rebellions and finally, old party elites using old institutional mechanisms to bring back democracy.[63]

European Union

The European Union (EU) is sometimes considered as a neoliberal organization as it facilitates free trade and freedom of movement. It erodes national protectionism and it limits national subsidies.[64] Others underline that the EU is not completely neoliberal as it leaves the possibility to develop welfare state policies.[65][66]

Germany

Neoliberal ideas were first implemented in West Germany. The economists around Ludwig Erhard drew on the theories they had developed in the 1930s and 1940s and contributed to West Germany’s reconstruction after the Second World War.[67] Erhard was a member of the Mont Pelerin Society and in constant contact with other neoliberals. He pointed out that he is commonly classified as neoliberal and that he accepted this classification.[68]

The ordoliberal Freiburg School was more pragmatic. The German neoliberals accepted the classical liberal notion that competition drives economic prosperity, but they argued that a laissez-faire state policy stifles competition as the strong devour the weak since monopolies and cartels could pose a threat to freedom of competition. They supported the creation of a well-developed legal system and capable regulatory apparatus. While still opposed to full-scale Keynesian employment policies or an extensive welfare state, German neoliberal theory was marked by the willingness to place humanistic and social values on par with economic efficiency. Alfred Müller-Armack coined the phrase "social market economy" to emphasize the egalitarian and humanistic bent of the idea.[5] According to Boas and Gans-Morse, Walter Eucken stated that "social security and social justice are the greatest concerns of our time".[5]

Erhard emphasized that the market was inherently social and did not need to be made so.[48] He hoped that growing prosperity would enable the population to manage much of their social security by self-reliance and end the necessity for a widespread welfare state. By the name of Volkskapitalismus, there were some efforts to foster private savings. However, although average contributions to the public old age insurance were quite small, it remained by far the most important old age income source for a majority of the German population, therefore despite liberal rhetoric the 1950s witnessed what has been called a "reluctant expansion of the welfare state". To end widespread poverty among the elderly the pension reform of 1957 brought a significant extension of the German welfare state which already had been established under Otto von Bismarck.[69] Rüstow, who had coined the label "neoliberalism", criticized that development tendency and pressed for a more limited welfare program.[48]

Hayek did not like the expression "social market economy", but stated in 1976 that some of his friends in Germany had succeeded in implementing the sort of social order for which he was pleading while using that phrase. However, in Hayek's view the social market economy's aiming for both a market economy and social justice was a muddle of inconsistent aims.[70] Despite his controversies with the German neoliberals at the Mont Pelerin Society, Ludwig von Mises stated that Erhard and Müller-Armack accomplished a great act of liberalism to restore the German economy and called this "a lesson for the US".[71] However, according to different research Mises believed that the ordoliberals were hardly better than socialists. As an answer to Hans Hellwig's complaints about the interventionist excesses of the Erhard ministry and the ordoliberals, Mises wrote: "I have no illusions about the true character of the politics and politicians of the social market economy". According to Mises, Erhard's teacher Franz Oppenheimer "taught more or less the New Frontier line of" President Kennedy's "Harvard consultants (Schlesinger, Galbraith, etc.)".[72]

In Germany, neoliberalism at first was synonymous with both ordoliberalism and social market economy. But over time the original term neoliberalism gradually disappeared since social market economy was a much more positive term and fit better into the Wirtschaftswunder (economic miracle) mentality of the 1950s and 1960s.[48]

Middle East

The Middle East experienced an onset of neoliberal policies from the late 1960s onwards.[73][74] Egypt is frequently linked to the standardisation of neoliberal policies, particularly with regard to the 'open-door' policies of President Anwar Sadat throughout the 1970s,[75] and Hosni Mubarak's successive economic reforms from 1981 to 2011.[76] These measures, known as al-Infitah, were later diffused across the region. In Tunisia, neoliberal economic policies are associated with Ben Ali's dictatorship,[77] where the linkages between authoritarianism and neoliberalism become clear.[78] Responses to globalisation and economic reforms in the Gulf have also been approached via a neoliberal analytical framework.[79]

China

Following the death of Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping led the country through far ranging market centered reforms, with the slogan of Xiǎokāng, that combined neoliberalism with centralized authoritarianism. These focused on agriculture, industry, education and science/defense.[80]

United Kingdom

| Part of the politics series on |

| Thatcherism |

|---|

|

|

During her tenure as Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher oversaw a number of neoliberal reforms including: tax reduction, reforming exchange rates, deregulation and privatisation.[81] These reforms were continued and supported by her successor John Major and although opposed by the Labour Party at the time, they were largely left unaltered when the latter returned to government in 1997. Instead, the Labour government under Tony Blair finished off a variety of uncompleted privatisation and deregulation measures.[82]

The Adam Smith Institute, a United Kingdom-based free market think tank and lobbying group formed in 1977 and a major driver of the aforementioned neoliberal reforms,[83] officially changed its libertarian label to neoliberal in October 2016.[84]

United States

David Harvey traces the rise of neoliberalism in the United States to Lewis Powell's 1971 confidential memorandum to the Chamber of Commerce.[80]:43 A call to arms to the business community to counter criticism of the free enterprise system, it was a significant factor in the rise of conservative organizations and think-tanks which advocated for neoliberal policies, such as the Business Roundtable, The Heritage Foundation, the Cato Institute, Citizens for a Sound Economy, Accuracy in Academia and the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research. For Powell, universities were becoming an ideological battleground, and he recommended the establishment of an intellectual infrastructure to serve as a counterweight to the increasingly popular ideas of Ralph Nader and other opponents of big business.[85][86][87] On the left, neoliberal ideas were developed and widely popularized by John Kenneth Galbraith while the Chicago School ideas were advanced and repackaged into a progressive, leftist perspective in Lester Thurow's influential 1980 book "The Zero-Sum Society".[88]

Early roots of neoliberalism were laid in the 1970s during the Carter administration, with deregulation of the trucking, banking and airline industries.[89][90][91] This trend continued into the 1980s under the Reagan administration, which included tax cuts, increased defense spending, financial deregulation and trade deficit expansion.[92] Likewise, concepts of supply-side economics, discussed by the Democrats in the 1970s, culminated in the 1980 Joint Economic Committee report "Plugging in the Supply Side". This was picked up and advanced by the Reagan administration, with Congress following Reagan's basic proposal and cutting federal income taxes across the board by 25% in 1981.[93]

During the 1990s, the Clinton administration also embraced neoliberalism[82] by supporting the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), continuing the deregulation of the financial sector through passage of the Commodity Futures Modernization Act and the repeal of the Glass–Steagall Act and implementing cuts to the welfare state through passage of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act.[92][94][95] The neoliberalism of the Clinton administration differs from that of Reagan as the Clinton administration purged neoliberalism of neoconservative positions on militarism, family values, opposition to multiculturalism and neglect of ecological issues.[81]:50–51 Writing in New York, journalist Jonathan Chait disputed accusations that the Democratic Party had been hijacked by neoliberals, saying that its policies have largely stayed the same since the New Deal. Instead, Chait suggested this came from arguments that presented a false dichotomy between free market economics and socialism, ignoring mixed economies.[96] Historian Walter Scheidel says that both parties shifted to promote free market capitalism in the 1970s, with the Democratic Party being "instrumental in implementing financial deregulation in the 1990s".[97]

New Zealand

In New Zealand, neoliberal economic policies were implemented under the Fourth Labour Government led by Prime Minister David Lange. These neoliberal policies are commonly referred to as Rogernomics, a portmanteau of “Roger” and “economics”, after Lange appointed Roger Douglas minister of finance in 1984.[98]

Lange’s government had inherited a severe balance of payments crisis as a result of the deficits from the previously implemented two-year freeze on wages and prices by preceding Prime Minister Robert Muldoon who had also stubbornly maintained an unsustainable exchange rate.[99] The inherited economic conditions lead Lange to remark “We ended up being run very similarly to a Polish shipyard.”[100] On 14 September 1984 Lange’s government held an Economic Summit to discuss the underlying problems in the New Zealand economy, which lead to advocacy of radical economic reform previously proposed by the Treasury Department.[101]

A reform program consisting of deregulation and the removal of tariffs and subsidies was put in place which consequently affected New Zealand’s agricultural community, who were hit hard by the loss of subsidies to farmers.[102] A superannuation surcharge was introduced, despite having promised not to reduce superannuation, resulting in Labour losing support from the elderly. The finance markets were also deregulated, removing restrictions on interests rates, lending and foreign exchange and in March 1985, the New Zealand dollar was floated.[103] Subsequently, a number of government departments were converted into state-owned enterprises which lead to great job loss: Electricity Corporation 3,000; Coal Corporation 4,000; Forestry Corporation 5,000; New Zealand Post 8,000.[102]

New Zealand became a part of a global economy. The focus in the economy shifted from the productive sector to finance as a result of zero restrictions on overseas money coming into the country. Finance capital outstripped industrial capital and subsequently, the manufacturing industry suffered approximately 76,000 job losses.[104]

Traditions

Austrian School

The Austrian School is a school of economic thought which bases its study of economic phenomena on the interpretation and analysis of the purposeful actions of individuals.[105][106][107] It derives its name from its origin in late-19th and early-20th century Vienna with the work of Carl Menger, Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, Friedrich von Wieser and others.[108] In 21st century usage by such economists as Mark Skousen, reference to the Austrian school often denotes a reference to the free-market economics of Friedrich Hayek who began his teaching in Vienna.[109]

Among the contributions of the Austrian School to economic theory are the subjective theory of value, marginalism in price theory and the formulation of the economic calculation problem.[110] Many theories developed by "first wave" Austrian economists have been absorbed into most mainstream schools of economics. These include Carl Menger's theories on marginal utility, Friedrich von Wieser's theories on opportunity cost and Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk's theories on time preference as well as Menger and Böhm-Bawerk's criticisms of Marxian economics. The Austrian School follows an approach, termed methodological individualism, a version of which was codified by Ludwig von Mises and termed "praxeology" in his book published in English as Human Action in 1949.[111]

The former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan, speaking of the originators of the School, said in 2000 that "the Austrian School have reached far into the future from when most of them practiced and have had a profound and, in my judgment, probably an irreversible effect on how most mainstream economists think in this country".[112] In 1987, Nobel laureate James M. Buchanan told an interviewer: "I have no objections to being called an Austrian. Hayek and Mises might consider me an Austrian but, surely some of the others would not".[113] Republican Congressman Ron Paul stated that he adheres to Austrian School economics and has authored six books which refer to the subject.[114][115] Paul's former economic adviser, investment dealer Peter Schiff,[116] also calls himself an adherent of the Austrian School.[117] Jim Rogers, investor and financial commentator, also considers himself of the Austrian School of economics.[118] Chinese economist Zhang Weiying, who is known in China for his advocacy of free market reforms, supports some Austrian theories such as the Austrian theory of the business cycle.[119]

Chicago School

| Part of a series on the |

| Chicago school of economics |

|---|

|

People Associates shown in italics |

|

Theories

|

|

Ideas

|

|

The Chicago school of economics describes a neoclassical school of thought within the academic community of economists, with a strong focus around the faculty of University of Chicago. Chicago macroeconomic theory rejected Keynesianism in favor of monetarism until the mid-1970s, when it turned to new classical macroeconomics heavily based on the concept of rational expectations.[120] The school is strongly associated with economists such as Milton Friedman, George Stigler, Ronald Coase and Gary Becker.[121] In the 21 century, economists such as Mark Skousen refer to Friedrich Hayek as a key economist who influenced this school in the 20th century having started his career in Vienna and the Austrian school of economics.[122]

The school emphasizes non-intervention from government and generally rejects regulation in markets as inefficient with the exception of central bank regulation of the money supply (i.e. monetarism). Although the school's association with neoliberalism is sometimes resisted by its proponents,[120] its emphasis on reduced government intervention in the economy and a laissez-faire ideology have brought about an affiliation between the Chicago school and neoliberal economics.[12][123]

Political policy aspects

Political freedom

In The Road to Serfdom, Hayek has argued: "Economic control is not merely control of a sector of human life which can be separated from the rest; it is the control of the means for all our ends".[62]

Later in his book Capitalism and Freedom (1962), Friedman developed the argument that economic freedom, while itself an extremely important component of total freedom, is also a necessary condition for political freedom. He commented that centralized control of economic activities was always accompanied with political repression.

In his view, the voluntary character of all transactions in an unregulated market economy and wide diversity that it permits are fundamental threats to repressive political leaders and greatly diminish power to coerce. Through elimination of centralized control of economic activities, economic power is separated from political power and the one can serve as counterbalance to the other. Friedman feels that competitive capitalism is especially important to minority groups since impersonal market forces protect people from discrimination in their economic activities for reasons unrelated to their productivity.[124]

Amplifying Friedman's argument, it has often been pointed out that increasing economic freedoms tend to raise expectations on political freedoms, eventually leading to democracy. Other scholars see the existence of non-democratic yet market-liberal regimes and the undermining of democratic control by market processes as strong evidence that such a general, ahistorical nexus cannot be upheld.[125] Contemporary discussion on the relationship between neoliberalism and democracy shifted to a more historical perspective, studying extent and circumstances of how much the two are mutually dependent, contradictory or incompatible.

Stanley Fish argues that neoliberalization of academic life may promote a narrower and in his opinion more accurate definition of academic freedom "as the freedom to do the academic job, not the freedom to expand it to the point where its goals are infinite". What Fish urges is "not an inability to take political stands, but a refraining from doing so in the name of academic responsibility".[126]

Criticism

Neoliberalism has received criticism both from the political left as well as the right,[127] in addition to myriad activists and academics.[128]

Focus on economic efficiency

Much of the literature in support of neoliberalism relies on the idea that neoliberal market logic improves a very narrow monetized conception of performance, which is not necessarily the best approach. This focus on economic efficiency can compromise other, perhaps more important factors. Anthropologist Mark Fleming argues that when the performance of a transit system is assessed purely in terms of economic efficiency, social goods such as strong workers' rights are considered impediments to maximum performance, which given the monetization of time means timely premium rapid networks.[129] Using the case study of the San Francisco Muni, Fleming shows that neoliberal worldview has resulted in vicious attacks on the drivers' union, for example through the setting of impossible schedules so that drivers are necessarily late and through brutal public smear campaigns. This ultimately resulted in the passing of Proposition G, which severely undermined the powers of the Muni drivers' union. Workers' rights are by no means the only victims of the neoliberal focus on economic efficiency as it is important to recognize that this vision and metric of performance judgment de-emphasizes literally every public good that is not conventionally monetized. For example, the geographers Birch and Siemiatycki contend that the growth of marketization ideology has shifted discourse such that it focuses on monetary rather than social objectives, making it harder to justify public goods driven by equity, environmental concerns and social justice.[130]

Class project

David Harvey described neoliberalism as a class project, designed to impose class on society through liberalism.[131] Economists Gérard Duménil and Dominique Lévy posit that "the restoration and increase of the power, income, and wealth of the upper classes" are the primary objectives of the neoliberal agenda[132] Economist David M. Kotz contends that neoliberalism "is based on the thorough domination of labor by capital".[39]:43 The emergence of the "precariat", a new class facing acute socio-economic insecurity and alienation, has been attributed to the globalization of neoliberalism.[133]

Sociologist Thomas Volscho argues that the imposition of neoliberalism in the United States arose from a conscious political mobilization by capitalist elites in the 1970s who faced two crises: the legitimacy of capitalism and a falling rate of profitability in industry. Various neoliberal ideologies (such as monetarism and supply-side economics) had been long advanced by elites, translated into policies by the Reagan administration and ultimately resulted in less governmental regulation and a shift from a tax-financed state to a debt-financed one. While the profitability of industry and the rate of economic growth never recovered to the heyday of the 1960s, the political and economic power of Wall Street and finance capital vastly increased due to the debt-financing of the state.[134]

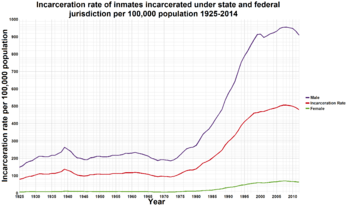

Several scholars have linked the rise of neoliberalism to unprecedented levels of mass incarceration of the poor in the United States.[2]:3, 346[136][137][138][139] Sociologist Loïc Wacquant argues that neoliberal policy for dealing with social instability among economically marginalized populations following the implementation of other neoliberal policies, which have allowed for the retrenchment of the social welfare state and the rise of punitive workfare and have increased gentrification of urban areas, privatization of public functions, the shrinking of collective protections for the working class via economic deregulation and the rise of underpaid, precarious wage labor, is the criminalization of poverty and mass incarceration.[137]:53–54[140] By contrast, it is extremely lenient in dealing with those in the upper echelons of society, in particular when it comes to economic crimes of the privileged classes and corporations such as fraud, embezzlement, insider trading, credit and insurance fraud, money laundering and violation of commerce and labor codes.[137][141] According to Wacquant, neoliberalism does not shrink government, but instead sets up a "centaur state" with little governmental oversight for those at the top and strict control of those at the bottom.[137][142]

In expanding upon Wacquant's thesis, sociologist and political economist John L. Campbell of Dartmouth College suggests that through privatization, the prison system exemplifies the centaur state:

On the one hand, it punishes the lower class, which populates the prisons; on the other hand, it profits the upper class, which owns the prisons, and it employs the middle class, which runs them.

In addition, he says the prison system benefits corporations through outsourcing as the inmates are "slowly becoming a source of low-wage labor for some US corporations". Both through privatization and outsourcing, Campbell argues, the penal state reflects neoliberalism.[145]:61 Campbell also argues that while neoliberalism in the United States established a penal state for the poor, it also put into place a debtor state for the middle class and that "both have had perverse effects on their respective targets: increasing rates of incarceration among the lower class and increasing rates of indebtedness—and recently home foreclosure—among the middle class"-[145]:68

David McNally, Professor of Political Science at York University, argues that while expenditures on social welfare programs have been cut, expenditures on prison construction have increased significantly during the neoliberal era, with California having "the largest prison-building program in the history of the world".[146] The scholar Bernard Harcourt contends the neoliberal concept that the state is inept when it comes to economic regulation, but efficient in policing and punishing "has facilitated the slide to mass incarceration.[147] Both Wacquant and Harcourt refer to this phenomenon as "Neoliberal Penality".[148][149]

Global health

The effect of neoliberalism on global health, particularly the aspect of international aid, involves key players such as non-governmental organizations (NGOs), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. According to James Pfeiffer,[150] neoliberal emphasis has been placed on free markets and privatization which has been tied to the "new policy agenda" in which NGOs are seen as being able to provide better social welfare than governments. International NGOs have been promoted to fill holes in public services created by the World Bank and IMF through their promotion of Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs) which reduce government health spending and which Pfeiffer criticized as unsustainable. The reduced health spending and the gain of the public health sector by NGOs causes the local health system to become fragmented, undermines local control of health programs and contributes to local social inequality between NGO workers and local individuals.[151]

In 2016, researchers for the IMF released a paper entitled "Neoliberalism: Oversold?", which stated:

There is much to cheer in the neoliberal agenda. The expansion of global trade has rescued millions from abject poverty. Foreign direct investment has often been a way to transfer technology and know-how to developing economies. Privatization of state-owned enterprises has in many instances led to more efficient provision of services and lowered the fiscal burden on governments.

However, it was also critical of some neoliberal policies, such as freedom of capital and fiscal consolidation for "increasing inequality, in turn jeopardizing durable expansion".[152] The authors also note that some neoliberal policies are to blame for financial crises around the world growing bigger and more damaging.[153] The report contends the implementation of neoliberal policies by economic and political elites has led to "three disquieting conclusions":

- The benefits in terms of increased growth seem fairly difficult to establish when looking at a broad group of countries.

- The costs in terms of increased inequality are prominent. Such costs epitomize the trade-off between the growth and equity effects of some aspects of the neoliberal agenda.

- Increased inequality in turn hurts the level and sustainability of growth. Even if growth is the sole or main purpose of the neoliberal agenda, advocates of that agenda still need to pay attention to the distributional effects.[154]

Writing in The Guardian, Stephen Metcalf posits that the IMF paper helps "put to rest the idea that the word is nothing more than a political slur, or a term without any analytic power".[155]

The IMF has itself been criticized for its neoliberal policies.[156][157] Rajesh Makwana writes that "the World Bank and IMF, are major exponents of the neoliberal agenda".[158] Sheldon Richman, editor of the libertarian journal The Freeman, also sees the IMF imposing "corporatist-flavored 'neoliberalism' on the troubled countries of the world". The policies of spending cuts coupled with tax increases give "real market reform a bad name and set back the cause of genuine liberalism". Paternalistic supranational bureaucrats foster "long-term dependency, perpetual indebtedness, moral hazard, and politicization, while discrediting market reform and forestalling revolutionary liberal change".[159]

Rowden wrote that the IMF’s monetarist approach towards prioritising price stability (low inflation) and fiscal restraint (low budget deficits) was unnecessarily restrictive and has prevented developing countries from scaling up long-term investment in public health infrastructure, resulting in chronically underfunded public health systems, demoralising working conditions that have fueled a "brain drain" of medical personnel and the undermining of public health and the fight against HIV/AIDS in developing countries.[160]

The implementation of neoliberal policies and the acceptance of neoliberal economic theories in the 1970s are seen by some academics as the root of financialization, with the financial crisis of 2007–2008 as one of the ultimate results.[161][42][162][163][39][164]

Infrastructure

Nicolas Firzli has argued that the rise of neoliberalism eroded the post-war consensus and Eisenhower-era Republican centrism that had resulted in the massive allocation of public capital to large-scale infrastructure projects throughout the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s in both Western Europe and North America: "In the pre-Reagan era, infrastructure was an apolitical, positively connoted, technocratic term shared by mainstream economists and policy makers […] including President Eisenhower, a praetorian Republican leader who had championed investment in the Interstate Highway System, America’s national road grid […] But Reagan, Thatcher, Delors and their many admirers amongst Clintonian, ‘New Labour’ and EU Social-Democrat decision makers in Brussels sought to dismantle the generous state subsidies for social infrastructure and public transportation across the United States, Britain and the European Union".[165]

Following Brexit, the 2016 United States presidential election and the progressive emergence of a new kind of "self-seeking capitalism" ("Trumponomics") moving away to some extent from the neoliberal orthodoxies of the past, we may witness a "massive increase in infrastructure investment" in the United States, Britain and other advanced economies:[166][167]

With the victory of Donald J. Trump on November 8, 2016, the 'neoliberal-neoconservative' policy consensus that had crystalized in 1979–1980 (Deng Xiaoping's visit to the United States, election of Reagan and Thatcher) finally came to an end [...] The deliberate neglect of America's creaking infrastructure assets (notably public transportation and water sanitation) from the early 1980s on eventually fueled a widespread popular discontent that came back to haunt both Hillary Clinton and the Republican establishment. Donald Trump was quick to seize on the issue to make a broader slap against the laissez-faire complacency of the federal government.[168]

Others such as Catherine Rottenberg do not see Trump's victory as an end to neoliberalism, but rather a new phase of it.[169]

Corporatocracy

Mark Arthur has written that the influence of neoliberalism has given rise to an "anti-corporatist" movement in opposition to it. This "anti-corporatist" movement is articulated around the need to re-claim the power that corporations and global institutions have stripped governments of. He says that Adam Smith's "rules for mindful markets" served as a basis for the anti-corporate movement, "following government's failure to restrain corporations from hurting or disturbing the happiness of the neighbor [Smith]".[170]

Environmental impact

Nicolas Firzli has argued that the neoliberal era was essentially defined by "the economic ideas of Milton Friedman, who wrote that 'if anything is certain to destroy our free society, to undermine its very foundation, it would be a widespread acceptance by management of social responsibilities in some sense other than to make as much money as possible. This is a fundamentally subversive doctrine'".[171] Firzli insists that prudent, fiduciary-driven long-term investors cannot ignore the environmental, social and corporate governance consequences of actions taken by the CEOs of the companies whose shares they hold as "the long-dominant Friedman stance is becoming culturally unacceptable and financially costly in the boardrooms of pension funds and industrial firms in Europe and North America".[171]

Political opposition

Counterpoints to neoliberalism:

- Globalization can subvert nations' ability for self-determination.[172]

- The replacement of a government-owned monopoly with private companies, each supposedly trying to provide the consumer with better value service than all of its private competitors, removes the efficiency that can be gained from the economy of scale.[173]

- Even if it could be shown that neoliberal capitalism increases productivity, it erodes the conditions in which production occurs long term, i.e. resources/nature, requiring expansion into new areas. It is therefore not sustainable within the world's limited geographical space.[174]

- Social and ecological damages: heterodox economists argue that neoliberalism is a system that socializes costs and privatizes profits. It is thus a system of unpaid costs and avoidance of responsibility. The main solution are seen in social controls of the economy to prevent damages, namely the precautionary principle and the reversal of the burden of proof. This markedly differs from neoclassical and neoliberal solutions that propose taxes, bargaining, or judicial process.[175][176]

- Exploitation: critics consider neoliberal economics to promote exploitation and social injustice.[177]

- Negative economic consequences: critics argue that neoliberal policies produce economic inequality.[2]:7

- Mass incarceration of the poor: some critics claim that neoliberal policies result in an expanding carceral state and the criminalization of poverty.[2]:3, 346[139]

- Increase in corporate power: some organizations and economists believe neoliberalism, unlike liberalism, changes economic and government policies to increase the power of corporations and a shift to benefit the upper classes.[178][179]

- Anti-democratic: some scholars contend that neoliberalism undermines the basic elements of democracy.[125][180]

- Urban citizens are increasingly deprived of the power to shape the basic conditions of daily life, which are instead being shaped exclusively by companies involved in competitive economy.[181]

- Trade-led, unregulated economic activity and lax state regulation of pollution lead to environmental impacts or degradation.[182]

- Deregulation of the labor market produces flexibilization and casualization of labor, greater informal employment and a considerable increase in industrial accidents and occupational diseases.[183]

- Mass extinction: according to David Harvey, "the era of neoliberalization also happens to be the era of the fastest mass extinction of species in the Earth's recent history".[80]:173

American scholar and cultural critic Henry Giroux alleges neoliberalism holds that market forces should organize every facet of society, including economic and social life; and promotes a social Darwinist ethic which elevates self-interest over social needs.[184][185][186]

According to the economists Howell and Diallo, neoliberal policies have contributed to a United States economy in which 30% of workers earn low wages (less than two-thirds the median wage for full-time workers) and 35% of the labor force is underemployed as only 40% of the working-age population in the country is adequately employed.[187]

The Center for Economic Policy Research's (CEPR) Dean Baker (2006) argued that the driving force behind rising inequality in the United States has been a series of deliberate, neoliberal policy choices including anti-inflationary bias, anti-unionism and profiteering in the health industry.[188] However, countries have applied neoliberal policies at varying levels of intensity—for example, the OECD has calculated that only 6% of Swedish workers are beset with wages it considers low and that Swedish wages are overall lower.[189] Others argue that Sweden's adoption of neoliberal reforms, in particular the privatization of public services and reduced state benefits, has resulted in income inequality growing faster in Sweden than any other OECD nation.[190][191]

The rise of anti-austerity parties in Europe and SYRIZA's victory in the Greek legislative elections of January 2015 have some proclaiming "the end of neoliberalism".[192]

Kristen R. Ghodsee, ethnographer and Professor of Russian and East European Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, asserts that the triumphalist attitudes of Western powers at the end of the Cold War and the fixation with linking all leftist political ideals with the excesses of Stalinism, permitted neoliberal, free market capitalism to fill the void, which undermined democratic institutions and reforms, leaving a trail of economic misery, unemployment and rising inequality throughout the former Eastern Bloc and much of the West in the following decades that has fueled the resurgence of extremist nationalisms in both the former and the latter.[193] In addition, her research shows that widespread discontent with neoliberal capitalism has also led to a "red nostalgia" (Nostalgia for the Soviet Union, Ostalgie, Yugo-nostalgia) in much of the former Communist bloc, noting that "the political freedoms that came with democracy were packaged with the worst type of unregulated, free market capitalism, which completely destabilized the rhythms of everyday life and brought crime, corruption and chaos where there had once been a comfortable predictability."[194]

Ruth J Blakeley, Professor of Politics and International Relations at the University of Sheffield, accuses the United States and its allies of fomenting state terrorism and mass killings during the Cold War as a means to buttress and promote the expansion of capitalism and neoliberalism in the developing world. As an example of this, Blakeley says the case of Indonesia demonstrates that the U.S. and Great Britain put the interests of capitalist elites over the human rights of hundreds of thousands of Indonesians by supporting the Indonesian Army as it waged a campaign of mass killings which resulted in the wholesale annihilation of the Communist Party of Indonesia and its civilian supporters.[195] Historian Bradley R. Simpson posits that this campaign of mass killings was "an essential building block of the neoliberal policies that the West would attempt to impose on Indonesia after Sukarno's ouster."[196]

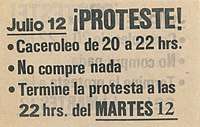

In Latin America, the "pink tide" that swept leftist governments into power at the turn of the millennium can be seen as a reaction against neoliberal hegemony and the notion that "there is no alternative" (TINA) to the Washington Consensus.[197]

Notable critics of neoliberalism in theory or practice include economists Joseph Stiglitz,[198] Amartya Sen, Michael Hudson,[199] Robert Pollin,[200] Julie Matthaei[201] and Richard D. Wolff;[179] linguist Noam Chomsky;[44] geographer and anthropologist David Harvey;[80] Slovenian continental philosopher Slavoj Žižek,[202] political activist and public intellectual Cornel West;[203] Marxist feminist Gail Dines;[204] author, activist and filmmaker Naomi Klein;[205] journalist and environmental activist George Monbiot;[206] Belgian psychologist Paul Verhaeghe;[207] journalist and activist Chris Hedges;[208] and the alter-globalization movement in general, including groups such as ATTAC. Critics of neoliberalism argue that not only is neoliberalism's critique of socialism (as unfreedom) wrong, but neoliberalism cannot deliver the liberty that is supposed to be one of its strong points.

In protest against neoliberal globalization, South Korean farmer and former president of the Korean Advanced Farmers Federation Lee Kyung-hae committed suicide by stabbing himself in the heart during a meeting of the WTO in Cancun, Mexico in 2003.[209] He was protesting against the decision of the South Korean government to reduce subsidies to farmers.[6]:96

See also

- Anarcho-capitalism

- Beltway libertarianism

- Capitalism

- Classical liberalism

- Cultural globalization

- Economic globalization

- Economic liberalism

- Elite theory

- Free market

- Globalism

- Globalization

- History of macroeconomic thought

- Inverted totalitarianism

- Market fundamentalism

- Neoclassical economics

- Neoclassical liberalism

- Neo-libertarianism

- Political Economy

- Reagan Democrat

- Reaganomics

- Right libertarianism

- Social Darwinism

- Technocracy

- Triangulation

- Trickle-down economics

- Washington Consensus

Notes

- ↑ See for example: Vincent, Andrew (2009). Modern Political Ideologies. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 337. ISBN 978-1405154956.

- 1 2 3 4 Stephen Haymes, Maria Vidal de Haymes and Reuben Miller (eds), The Routledge Handbook of Poverty in the United States, (London: Routledge, 2015), ISBN 0415673445

- ↑ Goldstein, Natalie (2011). Globalization and Free Trade. Infobase Publishing. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-8160-8365-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Springer, Simon; Birch, Kean; MacLeavy, Julie, eds. (2016). The Handbook of Neoliberalism. Routledge. p. 2. ISBN 978-1138844001.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Taylor C. Boas, Jordan Gans-Morse (June 2009). "Neoliberalism: From New Liberal Philosophy to Anti-Liberal Slogan". Studies in Comparative International Development. 44 (2): 137–61. doi:10.1007/s12116-009-9040-5.

- 1 2 3 Campbell Jones, Martin Parker, Rene Ten Bos (2005). For Business Ethics. Routledge.

ISBN 0415311357. p. 100:

- "Neoliberalism represents a set of ideas that caught on from the mid to late 1970s, and are famously associated with the economic policies introduced by Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom and Ronald Reagan in the United States following their elections in 1979 and 1981. The 'neo' part of neoliberalism indicates that there is something new about it, suggesting that it is an updated version of older ideas about 'liberal economics' which has long argued that markets should be free from intervention by the state. In its simplest version, it reads: markets good, government bad."

- ↑ Gérard Duménil and Dominique Lévy (2004). Capital Resurgent: Roots of the Neoliberal Revolution. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674011589 Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ↑ Jonathan Arac in Peter A. Hall and Michèle Lamont in Social Resilience in the Neoliberal Era (2013) pp. xvi–xvii

- The term is generally used by those who oppose it. People do not call themselves neoliberal; instead, they tag their enemies with the term.

- ↑ Collins English Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged © HarperCollins Publishers 1991, 1994, 1998, 2000, 2003

- ↑ "Neo-Liberal Ideas". World Health Organization.

- ↑ [4][5][6][7][8][9][10]

- 1 2 Palley, Thomas I (2004-05-05). "From Keynesianism to Neoliberalism: Shifting Paradigms in Economics". Foreign Policy in Focus. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ↑ Vincent, Andrew (2009). Modern Political Ideologies. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 339. ISBN 978-1405154956.

- 1 2 "Neoliberalism". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Taylor C. Boas, Jordan Gans-Morse (June 2009). "Neoliberalism: From New Liberal Philosophy to Anti-Liberal Slogan". Studies in Comparative International Development. 44 (2): 137–61. doi:10.1007/s12116-009-9040-5.

Neoliberalism has rapidly become an academic catchphrase. From only a handful of mentions in the 1980s, use of the term has exploded during the past two decades, appearing in nearly 1,000 academic articles annually between 2002 and 2005. Neoliberalism is now a predominant concept in scholarly writing on development and political economy, far outpacing related terms such as monetarism, neoconservatism, the Washington Consensus, and even market reform.

- 1 2 Springer, Simon; Birch, Kean; MacLeavy, Julie, eds. (2016). The Handbook of Neoliberalism. Routledge. p. 1. ISBN 978-1138844001.

Neoliberalism is easily one of the most powerful concepts to emerge within the social sciences in the last two decades, and the number of scholars who write about this dynamic and unfolding process of socio-spatial transformation is astonishing.

- ↑ Noel Castree (2013). A Dictionary of Human Geography. Oxford University Press. p. 339. ISBN 9780199599868.

'Neoliberalism' is very much a critics' term: it is virtually never used by those whom the critics describe as neoliberals.

- ↑ Daniel Stedman Jones (21 July 2014). Masters of the Universe: Hayek, Friedman, and the Birth of Neoliberal Politics. Princeton University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-4008-5183-6.

Friedman and Hayek are identified as the original thinkers and Thatcher and Reagan as the archetypal politicians of Western neoliberalism. Neoliberalism here has a pejorative connotation.

- ↑ Rowden, Rick (2016-07-06). "The IMF Confronts Its N-Word". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 2016-08-25.

- ↑ Springer, Simon; Birch, Kean; MacLeavy, Julie, eds. (2016). The Handbook of Neoliberalism. Routledge. p. 1. ISBN 978-1138844001.

Neoliberalism is a slippery concept, meaning different things to different people. Scholars have examined the relationships between neoliberalism and a vast array of conceptual categories.

- ↑ "Student heaps abuse on professor in 'neoliberalism' row". Retrieved 2017-01-25.

Colin Talbot, a professor at Manchester University, recently wrote it was such a broad term as to be meaningless and few people ever admitted to being neoliberals

- ↑ Taylor C. Boas, Jordan Gans-Morse (June 2009). "Neoliberalism: From New Liberal Philosophy to Anti-Liberal Slogan". Studies in Comparative International Development. 44 (2): 137–61. doi:10.1007/s12116-009-9040-5.

Neoliberalism shares many attributes with “essentially contested” concepts such as democracy, whose multidimensional nature, strong normative connotations, and openness to modification over time tend to generate substantial debate over their meaning and proper application.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Philip Mirowski, Dieter Plehwe, The road from Mont Pèlerin: the making of the neoliberal thought collective, Harvard University Press, 2009, ISBN 0-674-03318-3

- ↑ Springer, Simon; Birch, Kean; MacLeavy, Julie, eds. (2016). The Handbook of Neoliberalism. Routledge. p. 3. ISBN 978-1138844001.

- ↑ Pradella, Lucia; Marois, Thomas (2015). Polarising Development: Alternatives to Neoliberalism and the Crisis. United Kingdom: Pluto Press. pp. 1–11. ISBN 978-0745334691.

- ↑ Gide, Charles (1898-01-01). "Has Co-operation Introduced a New Principle into Economics?". The Economic Journal. 8 (32): 490–511. doi:10.2307/2957091. JSTOR 2957091.

- ↑ Angus Burgin (2012). The Great Persuasion: Reinventing Free Markets since the Depression. Harvard University Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-674-06743-1.

- ↑ Oliver Marc Hartwich, Neoliberalism: The Genesis of a Political Swearword, Centre for Independent Studies, 2009, ISBN 1-86432-185-7, p. 19

- ↑ Jörg Guido Hülsmann, Against the Neoliberals, Ludwig von Mises Institute, May 2012

- ↑ Taylor C. Boas, Jordan Gans-Morse (June 2009). "Neoliberalism: From New Liberal Philosophy to Anti-Liberal Slogan". Studies in Comparative International Development. 44 (2): 147. doi:10.1007/s12116-009-9040-5.

- ↑ David Brooks, The Vanishing Neoliberal, The New York Times, 2007

- ↑ Robin, Corey (April 28, 2016). "The First Neoliberals". Jacobin. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- ↑ Matt Welch, The Death of Contrarianism. The New Republic returns to its Progressive roots as a cheerleader for state power, Reason Magazine, May 2013

- ↑ Charles Peters, A Neoliberal's Manifesto, The Washington Monthly, May 1983

- ↑ Elizabeth Tandy Shermer, "Review," Journal of Modern History (Dec 2014) 86#4 pp. 884–90

- ↑ Kotz, David (2015). The Rise and Fall of Neoliberal Capitalism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 12.

- ↑ Borders, Max (2015-06-26). "Neoliberalism: Making a Boogeyman Out of a Buzzword | Max Borders". Retrieved 2017-01-24.

- ↑ "Global Village or Global Pillage?". Reason.com. 2001-07-01. Retrieved 2017-01-24.

- 1 2 3 David M Kotz, The Rise and Fall of Neoliberal Capitalism, (Harvard University Press, 2015), ISBN 0674725654

- ↑ Stedman Jones, Daniel (2012). Masters of the Universe: Hayek, Friedman, and the Birth of Neoliberal Politics. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691151571.

- ↑ Fred L. Block and Margaret R. Somers, The Power of Market Fundamentalism: Karl Polanyi's Critique, (Harvard University Press, 2014), ISBN 0674050711. p. 3.

- 1 2 Susan Braedley and Meg Luxton, Neoliberalism and Everyday Life, (McGill-Queen's University Press, 2010), ISBN 0773536922, p. 3

- ↑ Frances Goldin, Debby Smith, Michael Smith (2014). Imagine: Living in a Socialist USA. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0062305573 p. 125

- 1 2 3 Chomsky, Noam and McChesney, Robert W. (Introduction). Profit over People: Neoliberalism and Global Order. Seven Stories Press, 2011. ISBN 1888363827.

- ↑ Lester Spence, Knocking the Hustle: Against the Neoliberal Term in Black Politics. (Punctum Books, 2016), 3.

- ↑ Mirowski, Philip. "The Thirteen Commandments of Neoliberalism". The Utopian. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ↑ International data from Maddison, Angus. "Historical Statistics for the World Economy: 1–2003 AD". . Gold dates culled from historical sources, principally Eichengreen, Barry (1992). Golden Fetters: The Gold Standard and the Great Depression, 1919–1939. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506431-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Oliver Marc Hartwich, Neoliberalism: The Genesis of a Political Swearword, Centre for Independent Studies, 2009, ISBN 1-86432-185-7

- ↑

- ↑ George H. Nash, The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America Since 1945, Intercollegiate Studies Institute, 1976, ISBN 978-1-882926-12-1, pp. 26–27

- 1 2 Peter Winn (ed), Victims of the Chilean Miracle: Workers and Neoliberalism in the Pinochet Era, 1973–2002, (Duke University Press, 2004), ISBN 082233321X

- ↑ Pusey, M., 2003. Economic rationalism in Canberra: A nation-building state changes its mind. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Cameron Clyde R How the Federal Parliamentary Labor Party Lost Its Way Archived 2012-08-03 at Archive.is

- ↑ Neilson L and Harris B Chronology of superannuation and retirement income in Australia Archived 2011-09-09 at the Wayback Machine. Parliamentary Library, Canberra, July 2008

- ↑ Marginson S Tertiary Education: A revolution to what end? Online Opinion, 5 April 2005

- ↑ "Government Delivers on Promise to Phase Out Full Fee Degrees". Ministers' Media Centre, Australian Government. 2008-10-29. Retrieved 2018-07-10.

- ↑ Historia contemporánea de Chile III. La economía: mercados empresarios y trabajadores. 2002. Gabriel Salazar and Julio Pinto. pp. 49–62.

- ↑ Konrad Adenauer Foundation, Helmut Wittelsbürger, Albrecht von Hoff, Chile's Way to the Social Market Economy

- ↑ Pamela Constable and Arturo Valenzuela, A Nation of Enemies: Chile Under Pinochet, (W. W. Norton & Company, 1993), ISBN 0393309851, p. 219

- ↑ PBS Interview with Alejandro Foxley conducted March 26, 2001 for The Commanding Heights: The Battle for the World Economy. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- ↑ Klein, Naomi (2008). The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. Picador. ISBN 0312427999 p. 105

- 1 2 Friedrich Hayek, The Road to Serfdom, University Of Chicago Press; 50th Anniversary edition (1944), ISBN 0-226-32061-8 p. 95

- ↑ Javier Martínez, Alvaro Díaz, The United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, 1996, ISBN 0-8157-5478-7, pp. 3, 4

- ↑ Jacotine, Keshia (2017-06-22). "The split in neoliberalism on Brexit and the EU". SPERI. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ↑ Milward, Alan S. (2000). The European rescue of the nation-state. London, New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780203982150. OCLC 70767937.

- ↑ Warlouzet, Laurent (2017). Governing Europe in a globalizing world : neoliberalism and its alternatives following the 1973 oil crisis. London, New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 9781138729421. OCLC 993980643.

- ↑ Oliver Marc Hartwich, Neoliberalism: The Genesis of a Political Swearword, Centre for Independent Studies, 2009, ISBN 1-86432-185-7, p. 22

- ↑ Ludwig Erhard, Franz Oppenheimer, dem Lehrer und Freund, In: Ludwig Erhard, Gedanken aus fünf Jahrzehnten, Reden und Schriften, hrsg. v. Karl Hohmann, Düsseldorf u. a. 1988, S. 861, Rede zu Oppenheimers 100. Geburtstag, gehalten in der Freien Universität Berlin (1964).

- ↑ Werner Abelshauser, Deutsche Wirtschaftsgeschichte seit 1945, C.H.Beck, 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-510946, Seite 192

- ↑ Josef Drexl, Die wirtschaftliche Selbstbestimmung des Verbrauchers, J.C.B. Mohr, 1998, ISBN 3-16-146938-0, Abschnitt: Freiheitssicherung auch gegen den Sozialstaat, p. 144.

- ↑ Ralf Ptak, Vom Ordoliberalismus zur Sozialen Marktwirtschaft: Stationen des Neoliberalismus in Deutschland, 2004, pp. 18–19

- ↑ Guido Jorg Hulsmann, Mises: The Last Knight of Liberalism, ISBN 978-1933550183, pp. 1007–08

- ↑ Ayubi, Nazih N. (1995). Over-stating the Arab state : politics and society in the Middle East. London: I.B. Tauris. pp. 329–395. ISBN 9781441681966. OCLC 703424952.

- ↑ Laura., Guazzone, (2009). The Arab State and Neo-liberal Globalization : the Restructuring of State Power in the Middle East. New York: Garnet Publishing (UK) Ltd. ISBN 9780863725104. OCLC 887506789.

- ↑ Waterbury, John (1983). The Egypt of Nasser and Sadat : the political economy of two regimes. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400857357. OCLC 889252154.

- ↑ 1968-, Sulaymān, Samīr, (2011). The autumn of dictatorship : fiscal crisis and political change in Egypt under Mubarak. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804777735. OCLC 891400543.

- ↑ Murphy, Emma (1999). Economic and political change in Tunisia : from Bourguiba to Ben Ali. New York, N.Y.: St. Martin's Press in association with University of Durham. ISBN 0312221428. OCLC 40125756.

- ↑ Tsourapas, Gerasimos (2013). "The Other Side of a Neoliberal Miracle: Economic Reform and Political De-Liberalization in Ben Ali's Tunisia". Mediterranean Politics. 18 (1): 23–41.

- ↑ Hanieh, Adam (2011). Capitalism and class in the Gulf Arab states (1st ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780230119604. OCLC 743800844.

- 1 2 3 4 Harvey, David (2005). A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-928326-5.

- 1 2 Manfred B. Steger and Dr. Ravi K. Roy. Neoliberalism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2010. ISBN 019956051X.

- 1 2 Springer, Simon; Birch, Kean; MacLeavy, Julie, eds. (2016). The Handbook of Neoliberalism. Routledge. p. 144. ISBN 978-1138844001.

- ↑ Springer, Simon; Birch, Kean; MacLeavy, Julie, eds. (2016). The Handbook of Neoliberalism. Routledge. p. 374. ISBN 978-1138844001.

- ↑ "Coming Out as Neoliberals" The Adam Smith Institute, October 11, 2016.

- ↑ Kevin Doogan (2009). New Capitalism. Polity. ISBN 0745633250 p. 34.

- ↑ Powell, Lewis F. Jr. (August 23, 1971). "Attack of American Free Enterprise System". Archived from the original on January 16, 2012. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- ↑ David Harvey (July 23, 2016). "Neoliberalism Is a Political Project." Jacobin. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ↑ Stoller, Matt (Oct 24, 2016). "How Democrats Killed Their Populist Soul".

- ↑ Anderson, William L. (25 October 2000). "Rethinking Carter".

- ↑ Leonard, Andrew (4 June 2009). "No, Jimmy Carter did it".

- ↑ Firey, Thomas A. (February 20, 2011). "A salute to Carter, deregulation's hero".

- 1 2 Nikolaos Karagiannis, Zagros Madjd-Sadjadi, Swapan Sen (eds). The US Economy and Neoliberalism: Alternative Strategies and Policies. Routledge, 2013. ISBN 1138904910. p. 58

- ↑ Darrell M. West (1987). Congress and Economic Policy Making. p. 71. ISBN 978-0822974352.

- ↑ Food Stamps. Democracy Now! (1997-08-25). Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- ↑ Alan S. Blinder, Alan Blinder: Five Years Later, Financial Lessons Not Learned, Wall Street Journal, September 10, 2013 (Blinder summarizing causes of the "Great Recession": "Disgracefully bad mortgages created a problem. But wild and woolly customized derivatives—totally unregulated due to the odious Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000—blew the problem up into a catastrophe. Derivatives based on mortgages were a principal source of the reckless leverage that backfired so badly during the crisis, imposing huge losses on investors and many financial firms.")

- ↑ Chait, Jonathan (July 16, 2017). "How 'Neoliberalism' Became the Left's Favorite Insult of Liberals". New York. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- ↑ Scheidel, Walter (2017). The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century. Princeton University Press. p. 416. ISBN 978-0691165028.

In the United States, both of the dominant parties have shifted toward free-market capitalism. Even though analysis of roll call votes show that since the 1970s, Republicans have drifted farther to the right than Democrats have moved to the left, the latter were instrumental in implementing financial deregulation in the 1990s and focused increasingly on cultural issues such as gender, race, and sexual identity rather than traditional social welfare policies.

- ↑ Lange, David (2005). My Life. Viking. p. 143. ISBN 0-670-04556-X.

- ↑ Fiske, Edward B.; Ladd, Helen F. (2000). When Schools Compete: A Cautionary Tale. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. p. 27. ISBN 0-8157-2835-2.

- ↑ "David Lange, in his own words". The New Zealand Herald. 15 August 2005.

- ↑ Russell, Marcia (1996). Revolution: New Zealand from Fortress to Free Market. Hodder Moa Beckett. p. 75. ISBN 1869584287.

- 1 2 Russell, Marcia (1996). Revolution: New Zealand from Fortress to Free Market. Hodder Moa Becket. p. 80. ISBN 1869584287.

- ↑ Singleton, John (20 June 2012). "Reserve Bank - Reverse Bank, 1936 to 1984". Te Ara Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Bell, Judith (2006). I See Red. Wellington: Awa Press. pp. 22–56.

- ↑ Carl Menger, Principles of Economics, online at https://www.mises.org/etexts/menger/principles.asp

- ↑ "Methodological Individualism". Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ↑ Ludwig von Mises. Human Action, p. 11, "r. Purposeful Action and Animal Reaction". Referenced 2011-11-23.

- ↑ Joseph A. Schumpeter, History of economic analysis, Oxford University Press 1996, ISBN 978-0195105599.

- ↑ Mark Skouzen. Vienna and Chicago: Friends or Foes? A Tale of Two Schools of Free-Market Economics, (Capital Press, 2005) ISBN 0895260298

- ↑ Birner, Jack; van Zijp, Rudy (1994). Hayek, Co-ordination and Evolution: His Legacy in Philosophy, Politics, Economics and the History of Ideas. London, New York: Routledge. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-415-09397-2.

- ↑ Ludwig von Mises, Nationalökonomie (Geneva: Union, 1940), p. 3; Human Action (Auburn, Ala.: Mises Institute, [1949] 1998)

- ↑ Greenspan, Alan. "Hearings before the U.S. House of Representatives' Committee on Financial Services." U.S. House of Representatives' Committee on Financial Services. Washington D.C.. 25 July 2000.

- ↑ An Interview with Laureate James Buchanan Austrian Economics Newsletter: Volume 9, Number 1; Fall 1987

- ↑ "The Economics of a Free Society". Mises Institute. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ↑ Paul, Ron (2008). The Revolution: A Manifesto. Grand Central Publishing. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-446-53751-3.

- ↑ "Peter Schiff Named Economic Advisor to the Ron Paul 2008 Presidential Campaign". Reuters. 2008-01-25. Archived from the original on 2008-10-15.

- ↑ "Interview with Peter Schiff". Mises Institute. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ↑ Inside the House of Money: Top Hedge Fund Traders on Profiting in the Global Markets. 2006. Wiley. p. 230

- ↑ Weiyin, Zhang, "Completely bury Keynesianism", http://finance.sina.com.cn/20090217/10345864499_3.shtml (February 17, 2009)

- 1 2 Emmet, Ross; et al. (2010). The Elgar Companion to the Chicago School of Economics. Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd. p. 133. ISBN 978-1840648744.

- ↑ Mirowski, Philip (2009). The Road from Mont Pelerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective. Harvard University Press. p. 37. ISBN 0674033183.

- ↑ Mark Skousen. Vienna and Chicago: Friends or Foes? A Tale of Two Schools of Free-Market Economics, (Capital Press, 2005) ISBN 0895260298

- ↑ Biglaiser, Glen (January 2002). "The Internationalization of Chicago's Economics in Latin America". Economic Development and Cultural Change. 50 (2): 269–86. doi:10.1086/322875. JSTOR 322875.

- ↑ Milton Friedman. Capitalism and freedom. (2002). The University of Chicago. ISBN 0-226-26421-1 pp. 8–21

- 1 2 Wendy Brown, Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism's Stealth Revolution, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2015), ISBN 1935408534. p. 17.