Welfare state

The welfare state is a concept of government in which the state plays a key role in the protection and promotion of the economic and social well-being of its citizens. It is based on the principles of equality of opportunity, equitable distribution of wealth, and public responsibility for those unable to avail themselves of the minimal provisions for a good life. The general term may cover a variety of forms of economic and social organization.[1] The sociologist T. H. Marshall described the modern welfare state as a distinctive combination of democracy, welfare, and capitalism.[2]

Modern welfare states include Germany, France, Belgium and the Netherlands,[3] as well as the Nordic countries, such as Iceland, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Finland[4] which employ a system known as the Nordic model. Gøsta Esping-Andersen classified the most developed welfare state systems into three categories: social democratic, conservative, and liberal.[5][lower-alpha 1]

The welfare state involves a transfer of funds from the state to the services provided (i.e. healthcare, education, etc.) as well as directly to individuals ("benefits"), and is funded through taxation. It is often referred to as a type of mixed economy.[6] Such taxation usually includes a larger income tax for people with higher incomes, called a progressive tax.

Etymology

The German term sozialstaat ("social state") has been used since 1870 to describe state support programs devised by German sozialpolitiker ("social politicians") and implemented as part of Bismarck's conservative reforms.[7] In Germany, the term wohlfahrtsstaat, a direct translation of the English "welfare state", is used to describe Sweden's social insurance arrangements.

The literal English equivalent "social state" did not catch on in Anglophone countries.[8] However, during the Second World War, Anglican Archbishop William Temple, author of the book Christianity and the Social Order (1942), popularized the concept using the phrase "welfare state."[9] Bishop Temple's use of "welfare state" has been connected to Benjamin Disraeli's 1845 novel Sybil: or the Two Nations (in other words, the rich and the poor), where he writes "power has only one duty — to secure the social welfare of the PEOPLE".[10] At the time he wrote Sybil, Disraeli (later a prime minister) belonged to Young England, a conservative group of youthful Tories who disagreed with how the Whig dealt with the conditions of the industrial poor. Members of Young England attempted to garner support among the privileged classes to assist the less fortunate and to recognize the dignity of labor that they imagined had characterized England during the Feudal Middle Ages.[11]

The Swedish welfare state is called folkhemmet ("the people's home") and goes back to the 1936 compromise, as well as another important contract made in 1938, between Swedish trade unions and large corporations. Even though the country is often rated comparably economically free, Sweden's mixed economy remains heavily influenced by the legal framework and continual renegotiations of union contracts, a government-directed and municipality-administered system of social security, and a system of universal health care that is run by the more specialized and in theory more politically isolated county councils of Sweden.

The Italian term stato sociale ("social state") and the Turkish term sosyal devlet reproduces the original German term. In French, the concept is expressed as l'État-providence. Spanish and many other languages employ an analogous term: estado del bienestar – literally, "state of well-being". In Portuguese, two similar phrases exist: estado de bem-estar social, which means "state of social well-being", and estado de providência – "providing state", denoting the state's mission to ensure the basic well-being of the citizenry. In Brazil, the concept is referred to as previdência social, or "social providence".

Modern forms

Modern welfare programs are chiefly distinguished from earlier forms of poverty relief by their universal, comprehensive character. The institution of social insurance in Germany under Bismarck was an influential example. Some schemes were based largely in the development of autonomous, mutualist provision of benefits. Others were founded on state provision. In a highly influential essay, "Citizenship and Social Class" (1949), British sociologist T. H. Marshall identified modern welfare states as a distinctive combination of democracy, welfare, and capitalism, arguing that citizenship must encompass access to social, as well as to political and civil rights. Examples of such states are Germany, all of the Nordic countries, the Netherlands, France, Uruguay and New Zealand and the United Kingdom in the 1930s. Since that time, the term welfare state applies only to states where social rights are accompanied by civil and political rights.

Changed attitudes in reaction to the worldwide Great Depression, which brought unemployment and misery to millions, were instrumental in the move to the welfare state in many countries. During the Great Depression, the welfare state was seen as a "middle way" between the extremes of communism on the left and unregulated laissez-faire capitalism on the right.[6] In the period following World War II, many countries in Europe moved from partial or selective provision of social services to relatively comprehensive "cradle-to-grave" coverage of the population.

The activities of present-day welfare states extend to the provision of both cash welfare benefits (such as old-age pensions or unemployment benefits) and in-kind welfare services (such as health or childcare services). Through these provisions, welfare states can affect the distribution of wellbeing and personal autonomy among their citizens, as well as influencing how their citizens consume and how they spend their time.[12][13]

History of welfare states

Emperor Ashoka of India put forward his idea of a welfare state in the 3rd century BCE. He envisioned his dharma (religion or path) as not just a collection of high-sounding phrases. He consciously tried to adopt it as a matter of state policy; he declared that "all men and my children" and "whatever exertion I make, I strive only to discharge debt that I owe to all living creatures." It was a totally new ideal of kingship.[14] Ashoka renounced war and conquest by violence and forbade the killing of many animals.[15] Since he wanted to conquer the world through love and faith, he sent many missions to propagate Dharma. Such missions were sent to places like Egypt, Greece, and Sri Lanka. The propagation of Dharma included many measures of people's welfare. Centers of the treatment of men and beasts founded inside and outside of empire. Shady groves, wells, orchards and rest houses were laid out.[16] Ashoka also prohibited useless sacrifices and certain forms of gatherings which led to waste, indiscipline and superstition.[15] To implement these policies he recruited a new cadre of officers called Dharmamahamattas. Part of this group's duties was to see that people of various sects were treated fairly. They were especially asked to look after the welfare of prisoners.[17][18]

The concepts of welfare and pension were introduced in early Islamic law as forms of Zakat (charity), one of the Five Pillars of Islam, under the Rashidun Caliphate in the 7th century. This practice continued well into the Abbasid era of the Caliphate. The taxes (including Zakat and Jizya) collected in the treasury of an Islamic government were used to provide income for the needy, including the poor, elderly, orphans, widows, and the disabled. According to the Islamic jurist Al-Ghazali (Algazel, 1058–1111), the government was also expected to stockpile food supplies in every region in case a disaster or famine occurred. The Caliphate can thus be considered the world's first major welfare state.[19][20]

Historian Robert Paxton observes that on the European continent the provisions of the welfare state were originally enacted by conservatives in the late nineteenth century and by fascists in the twentieth in order to distract workers from unions and socialism, and were opposed by leftists and radicals. He recalls that the German welfare state was set up in the 1880s by Chancellor Bismarck, who had just closed 45 newspapers and passed laws banning the German Socialist Party and other meetings by trade unionists and socialists.[lower-alpha 2] A similar version was set up by Count Eduard von Taaffe in the Austro-Hungarian Empire a few years later. Legislation to help the working class in Austria emerged from Catholic conservatives. They turned to social reform by using Swiss and German models and intervening in state economic matters. They studied the Swiss Factory Act of 1877 that limited working hours for everyone, and gave maternity benefits, and German laws that insured workers against industrial risks inherent in the workplace. These served as the basis for Austria's 1885 Trade Code Amendment.[21]

"All the modern twentieth-century European dictatorships of the right, both fascist and authoritarian, were welfare states", Paxton writes. "They all provided medical care, pensions, affordable housing, and mass transport as a matter of course, in order to maintain productivity, national unity, and social peace."[22]

Continental European Marxists opposed piecemeal welfare measures as likely to dilute worker militancy without changing anything fundamental about the distribution of wealth and power. It was only after World War II, when they abandoned Marxism (in 1959 in West Germany, for example), that continental European socialist parties and unions fully accepted the welfare state as their ultimate goal.[22]

Great Britain

In Britain, the foundations for the welfare state originated with the Liberal Party under prime minister H. H. Asquith and Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George.[23] British liberals supported a capitalist economy and in the nineteenth-century had principally been concerned with issues of free trade (see classical liberalism), but by the turn of the twentieth century they shifted away from laissez faire economics and began to favor pro-active social legislation to assure equal opportunity for all citizens (and to counteract the appeal of the Labour Party). In this they were directly inspired by the signal success of the German economy under Bismarck's top-down social reforms.

France

The French welfare state originated in the 1930s during a period of socialist political ascendency, with the Matignon Accords and the reforms of the Popular Front/[24] Paxton points out these reforms were paralleled and even exceeded by measures taken by the Vichy regime in the 1940s.

By country or region

Australia

Prior to 1900 in Australia, charitable assistance from benevolent societies, sometimes with financial contributions from the authorities, was the primary means of relief for people not able to support themselves.[25] The 1890s economic depression and the rise of the trade unions and the Labor parties during this period led to a movement for welfare reform.[26]

In 1900, the states of New South Wales and Victoria enacted legislation introducing non-contributory pensions for those aged 65 and over. Queensland legislated a similar system in 1907 before the federal labor government led by Andrew Fisher introduced a national aged pension under the Invalid and Old-Aged Pensions Act 1908. A national invalid disability pension was started in 1910, and a national maternity allowance was introduced in 1912.[25][27]

During the Second World War, Australia under a labor government created a welfare state by enacting national schemes for: child endowment in 1941; a widows' pension in 1942; a wife’s allowance in 1943; additional allowances for the children of pensioners in 1943; and unemployment, sickness, and special benefits in 1945.[25][27]

Germany

Otto von Bismarck, the first Chancellor of Germany (in office 1871–90), developed the modern welfare state by building on a tradition of welfare programs in Prussia and Saxony that had begun as early as in the 1840s. The measures that Bismarck introduced – old-age pensions, accident insurance, and employee health insurance – formed the basis of the modern European welfare state. His paternalistic programs aimed to forestall social unrest (specifically to prevent an uprising like that of the Paris Commune in 1871), to undercut the appeal of the Social Democratic Party, and to secure the support of the working classes for the German Empire, as well as to reduce emigration to the United States, where wages were higher but welfare did not exist.[28][29] Bismarck further won the support of both industry and skilled workers through his high-tariff policies, which protected profits and wages from American competition, although they alienated the liberal intellectuals who wanted free trade.[30][31] During the 12 years of Hitler’s Third Reich, the National Socialists expanded and extended the welfare state to the point where over 17 million German citizens were receiving assistance under the auspices of the National Socialist People's Welfare (NSV) by 1939, an agency that had projected a powerful image of caring and support.[32]

Latin America

Welfare states in Latin America have been considered as 'welfare states in transition'[33] or 'emerging welfare states'.[34] Mesa-Lago has classified the countries taking into account the historical experience of their welfare systems.[35] The pioneers were Uruguay, Chile and Argentina, as they started to develop the first welfare programs in the 1920s following a bismarckian model. Other countries such as Costa Rica developed a more universal welfare system (1960s–1970s) with social security programs based on the Beveridge model.[36] Researchers such as Martinez-Franzoni [37] and Barba-Solano [38] have examined and identified several welfare regime models based on the typology of Esping-Andersen. Other scholars such as Riesco[39] and Cruz-Martinez [40] have examined the welfare state development in the region.

According to Alex Segura-Ubiergo:

Latin American countries can be unequivocally divided into two groups depending on their 'welfare effort' levels. The first group, which for convenience we may call welfare states, includes Uruguay, Argentina, Chile, Costa Rica, and Brazil. Within this group, average social spending per capita in the 1973–2000 period was around $532, while as a percentage of GDP and as a share of the budget, social spending reached 51.6 and 12.6 percent, respectively. In addition, between approximately 50 and 75 percent of the population is covered by the public health and pension social security system. In contrast, the second group of countries, which we call non-welfare states, has welfare-effort indices that range from 37 to 88. Within this second group, social spending per capita averaged $96.6, while social spending as a percentage of GDP and as a percentage of the budget averaged 5.2 and 34.7 percent, respectively. In terms of the percentage of the population actually covered, the percentage of the active population covered under some social security scheme does not even reach 10 percent.[41]

Middle East

Saudi Arabia,[42][43][44] Kuwait,[45] and Qatar have become welfare states exclusively for their own citizens.

People's Republic Of China

China traditionally relied on the extended family to provide welfare services.[46] The one-child policy introduced in 1978 has made that unrealistic, and new models have emerged since the 1980s as China has rapidly become richer and more urban. Much discussion is underway regarding China's proposed path toward a welfare state.[47][48] Chinese policies have been incremental and fragmented in terms of social insurance, privatization, and targeting. In the cities, where the rapid economic development has centered, lines of cleavage, have developed between state-sector and non-state-sector employees and between labor-market insiders and outsiders.[49]

United Kingdom

Historian Derek Fraser tells the British story in a nutshell:

- It germinated in the social thought of late Victorian liberalism, reached its infancy in the collectivism of the pre-and post-Great War statism, matured in the universalism of the 1940s and flowered in full bloom in the consensus and affluence of the 1950s and 1960s. By the 1970s it was in decline, like the faded rose of autumn. Both UK and US governments are pursuing in the 1980s monetarist policies inimical to welfare.[50]

The modern welfare state in Great Britain began operations with the Liberal welfare reforms of 1906–1914 under Liberal Prime Minister H. H. Asquith.[51] These included the passing of the Old-Age Pensions Act in 1908, the introduction of free school meals in 1909, the 1909 Labour Exchanges Act, the Development Act 1909, which heralded greater Government intervention in economic development, and the enacting of the National Insurance Act 1911 setting up a national insurance contribution for unemployment and health benefits from work.[52][53]

The minimum wage was introduced in Great Britain in 1909 for certain low-wage industries and expanded to numerous industries, including farm labour, by 1920. However, by the 1920s, a new perspective was offered by reformers to emphasize the usefulness of family allowance targeted at low-income families was the alternative to relieving poverty without distorting the labour market.[54][55] The trade unions and the Labour Party adopted this view. In 1945, family allowances were introduced; minimum wages faded from view. Talk resumed in the 1970s, but in the 1980s the Thatcher administration made it clear it would not accept a national minimum wage. Finally, with the return of Labour, the National Minimum Wage Act 1998 set a minimum of ₤3.60 per hour, with lower rates for younger workers. It largely affected workers in high turnover service industries such as fast food restaurants, and members of ethnic minorities.[56]

December 1942 saw the publication of the Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee on Social Insurance and Allied Services, commonly known as the Beveridge Report after its chairman, Sir William Beveridge. The Beveridge Report proposed a series of measures to aid those who were in need of help, or in poverty and recommended that the government find ways of tackling what the report called "the five giants": Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor, and Idleness. It urged the government to take steps to provide citizens with adequate income, adequate health care, adequate education, adequate housing, and adequate employment, proposing that "All people of working age should pay a weekly National Insurance contribution. In return, benefits would be paid to people who were sick, unemployed, retired, or widowed."

The Beveridge Report assumed that:

- the National Health Service would provide free health care to all citizens

- a Universal Child Benefit would give benefits to parents, encouraging people to have children by enabling them to feed and support a family

The report stressed the lower costs and efficiency of universal benefits. Beveridge cited miners' pension schemes as examples of some of the most efficient available and argued that a universal state scheme would be cheaper than a myriad of individual friendly societies and private insurance schemes and also less expensive to administer than a means-tested government-run welfare system for the poor.

The Liberal Party, the Conservative Party, and then the Labour Party all adopted the Beveridge Report's recommendations.[57] Following the Labour election victory in the 1945 general election many of Beveridge's reforms were implemented through a series of Acts of Parliament. On 5 July 1948, the National Insurance Act, National Assistance Act and National Health Service Act came into force, forming the key planks of the modern UK welfare state. In 1949, the Legal Aid and Advice Act was passed, providing the "fourth pillar"[58] of the modern welfare state, access to advice for legal redress for all.

Before 1939, most health care had to be paid for through non-government organisations – through a vast network of friendly societies, trade unions, and other insurance companies, which counted the vast majority of the UK working population as members. These organizations provided insurance for sickness, unemployment, and disability, providing an income to people when they were unable to work. As part of the reforms, the Church of England also closed down its voluntary relief networks and passed the ownership of thousands of church schools, hospitals and other bodies to the state.[59]

Welfare systems continued to develop over the following decades. By the end of the 20th century parts of the welfare system had been restructured, with some provision channelled through non-governmental organizations which became important providers of social services.[60]

United States

The United States developed a limited welfare state in the 1930s.[61] The earliest and most comprehensive philosophical justification for the welfare state was produced by an American, the sociologist Lester Frank Ward (1841–1913), whom the historian Henry Steele Commager called "the father of the modern welfare state".

Ward saw social phenomena as amenable to human control. "It is only through the artificial control of natural phenomena that science is made to minister to human needs" he wrote, "and if social laws are really analogous to physical laws, there is no reason why social science should not receive practical application such as have been given to physical science."[62] Ward wrote:

The charge of paternalism is chiefly made by the class that enjoys the largest share of government protection. Those who denounce it are those who most frequently and successfully invoke it. Nothing is more obvious today than the single inability of capital and private enterprise to take care of themselves unaided by the state; and while they are incessantly denouncing "paternalism," by which they mean the claim of the defenseless laborer and artisan to a share in this lavish state protection, they are all the while besieging legislatures for relief from their own incompetency, and "pleading the baby act" through a trained body of lawyers and lobbyists. The dispensing of national pap to this class should rather be called "maternalism," to which a square, open, and dignified paternalism would be infinitely preferable. [63]

Ward's theories centred around his belief that a universal and comprehensive system of education was necessary if a democratic government was to function successfully. His writings profoundly influenced younger generations of progressive thinkers such as Theodore Roosevelt, Thomas Dewey, and Frances Perkins (1880–1965), among others.[64]

The United States was the only industrialized country that went into the Great Depression of the 1930s with no social insurance policies in place. In 1935 Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal instituted significant social insurance policies. In 1938 Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act, limiting the work week to 40 hours and banning child labor for children under 16, over stiff congressional opposition from the low-wage South.[61]

The Social Security law was very unpopular among many groups – especially farmers, who resented the additional taxes and feared they would never be made good. They lobbied hard for exclusion. Furthermore, the Treasury realized how difficult it would be to set up payroll deduction plans for farmers, for housekeepers who employed maids, and for non-profit groups; therefore they were excluded. State employees were excluded for constitutional reasons (the federal government in the United States cannot tax state governments). Federal employees were also excluded.

By 2013 the U.S. remained the only major industrial state without a uniform national sickness program. American spending on health care (as percent of GDP) is the highest in the world, but it is a complex mix of federal, state, philanthropic, employer and individual funding. The US spent 16% of its GDP on health care in 2008, compared to 11% in France in second place.[65]

Some scholars, such as Gerard Friedman, argue that labor-union weakness in the Southern United States undermined unionization and social reform throughout the United States as a whole, and is largely responsible for the anaemic U.S. welfare state.[66] Sociologists Loïc Wacquant and John L. Campbell contend that since the rise of neoliberal ideology in the late 1970s and early 1980s, an expanding carceral state, or government system of mass incarceration, has largely supplanted the increasingly retrenched social welfare state, which has been justified by its proponents with the argument that the citizenry must take on personal responsibility.[67][68][69] Scholars assert that this transformation of the welfare state to a post-welfare punitive state, along with neoliberal structural adjustment policies and the globalization of the U.S. economy, have created more extreme forms of "destitute poverty" in the U.S. which must be contained and controlled by expanding the criminal justice system into every aspect of the lives of the poor.[70]

Three worlds of the welfare state

| Social democracy |

|---|

|

|

People

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Christian democracy |

|---|

|

|

Ideas

|

|

Broadly speaking, welfare states are either universal – with provisions that cover everybody, or selective – with provisions covering only those deemed most needy. In his 1990 book, The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, Danish sociologist Gøsta Esping-Andersen further identified three subtypes of welfare state models.[71] Though increasingly criticised, these classifications are still used as a starting point in analysis of modern welfare states[lower-alpha 3] and remain a fundamental heuristic tool for welfare state scholars. Even for those who claim that in-depth analysis of a single case is more suited to capture the complexity of different social policy arrangements, welfare typologies can provide a comparative lens that can help to place single cases in perspective.[72]:598

Esping-Andersen's welfare classification acknowledges the historical role of three dominant twentieth-century Western European and American political movements: Social Democracy (socialism), Christian Democracy (conservatism); and Liberalism.[72][73]

- The Social-Democratic welfare state model is based on the principle of Universalism, granting access to benefits and services based on citizenship. Such a welfare state is said to provide a relatively high degree of citizen autonomy, limiting reliance on family and market.[72]:584 In this context, social policies are perceived as "politics against the market".[74]

- The Christian-Democratic welfare state model is based on the principle of subsidiarity (decentralization) and the dominance of social insurance schemes, offering a medium level of decommodification and permitting a high degree of social stratification.

- The Liberal model is based on market dominance and private provision; ideally, in this model, the state only interferes to ameliorate poverty and provide for basic needs, largely on a means-tested basis. Hence, the decommodification potential of state benefits is assumed to be low and social stratification high.[72]:584

Based on the decommodification index, Esping-Andersen divided 18 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries into the following groups:[75]

- Social Democratic: Denmark, Finland, Netherlands, Norway and Sweden

- Christian Democratic: Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy and Spain

- Liberal: Australia, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, Switzerland and US

- Not clearly classified: Ireland and United Kingdom

Since the building of the decommodification index is limited[76] and the typology is debatable, these 18 countries could be ranked from most purely social-democratic (Sweden) to the most liberal (the United States).[72]:597 Ireland represents a near-hybrid model whereby two streams of unemployment benefit exist: contributory and means-tested. However, payments can begin immediately and are theoretically available to all Irish citizens even if they have never worked, provided they are habitually resident.[77]

Swedish professor of political science Bo Rothstein points out that in non-universal welfare states, the state is primarily concerned with directing resources to "the people most in need". This requires tight bureaucratic control in order to determine who is eligible for assistance and who is not. Under universal models such as Sweden, on the other hand, the state distributes welfare to all people who fulfill easily established criteria (e.g. having children, receiving medical treatment, etc.) with as little bureaucratic interference as possible. This, however, requires higher taxation due to the scale of services provided. This model was constructed by the Scandinavian ministers Karl Kristian Steincke and Gustav Möller in the 1930s and is dominant in Scandinavia.[78]

Sociologist Lane Kenworthy argues that the Nordic experience demonstrates that the modern social democratic model can "promote economic security, expand opportunity, and ensure rising living standards for all ... while facilitating freedom, flexibility and market dynamism."[79]

Finally, scholars have also proposed to classify welfare regimes using 'outcomes', such as inequalities, poverty rates, response to different social risks, rather than simply focusing on institutional configurations.[80]

American political scientist Benjamin Radcliff has also argued that the universality and generosity of the welfare state (i.e. the extent of decommodification) is the single most important societal-level structural factor affecting the quality of human life, based on the analysis of time serial data across both the industrial democracies and the American States. He maintains that the welfare state improves life for everyone, regardless of social class (as do similar institutions, such as pro-worker labor market regulations and strong labor unions).[81][lower-alpha 4]

Effects of welfare on poverty

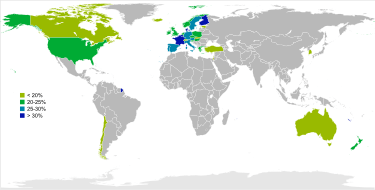

Empirical evidence suggests that taxes and transfers considerably reduce poverty in most countries whose welfare states constitute at least a fifth of GDP.[82][83]

| Country | Absolute poverty rate (1960–1991) (threshold set at 40% of U.S. median household income)[82] |

Relative poverty rate (1970–1997)[83] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-welfare | Post-welfare | Pre-welfare | Post-welfare | |

| 23.7 | 5.8 | 14.8 | 4.8 | |

| 9.2 | 1.7 | 12.4 | 4.0 | |

| 22.1 | 7.3 | 18.5 | 11.5 | |

| 11.9 | 3.7 | 12.4 | 3.1 | |

| 26.4 | 5.9 | 17.4 | 4.8 | |

| 15.2 | 4.3 | 9.7 | 5.1 | |

| 12.5 | 3.8 | 10.9 | 9.1 | |

| 22.5 | 6.5 | 17.1 | 11.9 | |

| 36.1 | 9.8 | 21.8 | 6.1 | |

| 26.8 | 6.0 | 19.5 | 4.1 | |

| 23.3 | 11.9 | 16.2 | 9.2 | |

| 16.8 | 8.7 | 16.4 | 8.2 | |

| 21.0 | 11.7 | 17.2 | 15.1 | |

| 30.7 | 14.3 | 19.7 | 9.1 | |

Effects of social expenditure on economic growth, public debt and education

Researchers have found very little correlation between economic performance and social expenditure.[84] They also see little evidence that social expenditures contribute to losses in productivity; economist Peter Lindert of the University of California, Davis attributes this to policy innovations such as the implementation of "pro-growth" tax policies in real-world welfare states.[85]

Nor have social expenses contributed significantly to public debt.

According to the OECD, social expenditures in its 34 member countries rose steadily between 1980 and 2007, but the increase in costs was almost completely offset by GDP growth. More money was spent on welfare because more money circulated in the economy and because government revenues increased. In 1980, the OECD averaged social expenditures equal to 16 percent of GDP. In 2007, just before the financial crisis kicked into full gear, they had risen to 19 percent – a manageable increase.[86]

A Norwegian study covering the period 1980 to 2003 found welfare state spending correlated negatively with student achievement.[87] However, many of the top-ranking OECD countries on the 2009 PISA tests are considered welfare states.[88]

The table below shows: first – social expenditure as a percentage of GDP for selected OECD member states; second – GDP per capita (PPP US$) in 2013:

| Nation | Social expenditure (% of GDP)[89] | Year[90] | GDP per capita (PPP US$)[91] |

Actual amount of social expenditure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31.9 | 2014 | $36,907 | $11,773 | |

| 31.0 | 2014 | $38,251 | $11,858 | |

| 30.7 | 2014 | $40,338 | $12,384 | |

| 30.1 | 2014 | $42,764 | $12,872 | |

| 28.6 | 2014 | $34,303 | $9,811 | |

| 28.4 | 2014 | $44,149 | $12,538 | |

| 28.1 | 2014 | $43,533 | $12,233 | |

| 26.8 | 2014 | $34,527 | $9,253 | |

| 25.8 | 2014 | $43,332 | $11,180 | |

| 25.2 | 2014 | $25,900 | $6,527 | |

| 24.7 | 2014 | $43,404 | $10,721 | |

| 24.0 | 2014 | $25,651 | $6,156 | |

| 23.7 | 2014 | $28,298 | $6,707 | |

| 23.5 | 2013 | $90,790 | $21,336 | |

| 23.1 | 2011 | $36,315 | $8,389 | |

| 22.1 | 2014 | $22,878 | $5,056 | |

| 22.0 | 2014 | $65,461 | $14,401 | |

| 21.7 | 2014 | $35,760 | $7,760 | |

| 21.0 | 2014 | $43,304 | $9,094 | |

| 20.8 | 2013 | $34,826 | $7,244 | |

| 20.6 | 2014 | $23,275 | $4,795 | |

| 20.6 | 2014 | $27,344 | $5,633 | |

| 19.4 | 2014 | $53,672 | $10,412 | |

| 19.2 | 2014 | $53,143 | $10,203 | |

| 19.0 | 2014 | $43,550 | $8,275 | |

| 18.4 | 2014 | $26,114 | $4,805 | |

| 17.0 | 2014 | $43,247 | $7,352 | |

| 16.5 | 2014 | $39,996 | $6,599 | |

| 16.3 | 2014 | $25,049 | $4,083 | |

| 15.0 | 2013 | $32,760 | $4,914 | |

| 12.5 | 2013 | $18,975 | $2,372 | |

| 10.4 | 2014 | $33,140 | $3,447 | |

| 10.0 | 2013 | $21,911 | $2,191 | |

| 7.9 | 2012 | $16,463 | $1,301 |

Criticism and response

Early conservatives, under the influence of Thomas Malthus, opposed every form of social insurance "root and branch". They argued, according to economist Brad DeLong, that it would "make the poor richer, and they would become more fertile. As a result, farm sizes would drop (as land was divided among ever more children), labor productivity would fall, and the poor would become even poorer. Social insurance was not just pointless; it was counterproductive."[92] Malthus, a clergyman for whom birth control was anathema, believed that the poor needed to learn the hard way to practice frugality, self-control and chastity. Traditional conservatives also protested that the effect of social insurance would be to weaken private charity and loosen traditional social bonds of family, friends, religious and non-governmental welfare organisations.[93]

Karl Marx, on the other hand, opposed piecemeal reforms advanced by middle-class reformers out of a sense of duty. In his Address of the Central Committee to the Communist League, written after the failed revolution of 1848, he warned that measures designed to increase wages, improve working conditions and provide social insurance were merely bribes that would temporarily make the situation of working classes tolerable to weaken the revolutionary consciousness that was needed to achieve a socialist economy.[lower-alpha 5] Nevertheless, Marx also proclaimed that the Communists had to support the bourgeoisie wherever it acted as a revolutionary progressive class because "bourgeois liberties had first to be conquered and then criticised".[95]

In the 20th century, opponents of the welfare state have expressed apprehension about the creation of a large, possibly self-interested, bureaucracy required to administer it and the tax burden on the wealthier citizens that this entailed.[96]

Political historian Alan Ryan points out that the modern welfare state stops short of being an "advance in the direction of socialism.... its egalitarian elements are more minimal than either its defenders or its critics think". It does not entail advocacy for social ownership of industry. The modern welfare state, Ryan writes, does not set out

to make the poor richer and the rich poorer, which is a central element in socialism, but to help people to provide for themselves in sickness while they enjoy good health, to put money aside to cover unemployment while they are in work, and to have adults provide for the education of their own and other people's children, expecting those children's future taxes to pay in due course for the pensions of their parents’ generation. These are devices for shifting income across different stages in life, not for shifting income across classes. Another distinct difference is that social insurance does not aim to transform work and working relations; employers and employees pay taxes at a level they would not have done in the nineteenth century, but owners are not expropriated, profits are not illegitimate, cooperativism does not replace hierarchical management.[97]

Historian Walter Scheidel has commented that the establishment of welfare states in the West in the early 20th century could be partly a reaction by elites to the Bolshevik Revolution and its violence against the bourgeoisie, which feared violent revolution in its own backyard. They were diminished decades later as the perceived threat receded:

It's a little tricky because the US never really had any strong leftist movement. But if you look at Europe, after 1917 people were really scared about communism in all the Western European countries. You have all these poor people, they might rise up and kill us and take our stuff. That wasn't just a fantasy because it was happening next door. And that, we can show, did trigger steps in the direction of having more welfare programs and a rudimentary safety net in response to fear of communism. Not that they [the communists] would invade, but that there would be homegrown movements of this sort. American populism is a little different because it's more detached from that. But it happens roughly at the same time, and people in America are worried about communism, too – not necessarily very reasonably. But that was always in the background. And people have only begun to study systematically to what extent the threat, real or imagined, of this type of radical regime really influenced policy changes in Western democracies. You don't necessarily even have to go out and kill rich people – if there was some plausible alternative out there, it would arguably have an impact on policy making at home. That's certainly there in the 20s, 30s, 40s, 50s, and 60s. And there's a debate, right, because it becomes clear that the Soviet Union is really not in very good shape, and people don't really like to be there, and all these movements lost their appeal. That's a contributing factor, arguably, that the end of the Cold War coincides roughly with the time when inequality really starts going up again, because elites are much more relaxed about the possibility of credible alternatives or threats being out there.[98]

See also

- Constitutional economics

- Corporate welfare

- Fifth power

- Flexicurity

- Free rider problem

- Happiness economics

- Hidden welfare state

- Nanny state

- Social policy

- Social protection

- Social stratification

- State Socialism (Germany)

- Unintended consequences

- Welfare capitalism

- Welfare reform

- Welfare state in the United Kingdom

Models:

Transfer of wealth:

Housing:

Notes

- ↑ For a revision of his typology, see Ferragina and Seeleib-Kaiser (2011)

- ↑ These laws had no effect and were allowed to lapse in 1890.

- ↑ For a review of the debate on the Three worlds of Welfare Capitalism, see Art and Gelissen (2002) and Ferragina and Seeleib-Kaiser (2011).

- ↑ See also "this collection of full-text peer reviewed scholarly articles on this subject" by Radcliff and colleagues (such as "Social Forces," "The Journal of Politics," and "Perspectives on Politics," among others)

- ↑ "However, the democratic petty bourgeois want better wages and security for the workers, and hope to achieve this by an extension of state employment and by welfare measures; in short, they hope to bribe the workers with a more or less disguised form of alms and to break their revolutionary strength by temporarily rendering their situation tolerable."[94]

References

- ↑ "Welfare state". Britannica Online Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Marshall, Thomas Humphrey (1950). Citizenship and Social Class: And Other Essays. Cambridge: University Press.

- ↑ Shorto, Russell (29 April 2009). "Going Dutch". The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ↑ Edwards, Paul K.; Elger, Tony (1999). The global economy, national states and the regulation of labour. p. 111.

- ↑ Esping-Andersen (1990)

- 1 2 O'Hara, Phillip Anthony, ed. (1999). "Welfare state". Encyclopedia of Political Economy. Routledge. p. 1245.

- ↑ Fay, S. B. (January 1950). "Bismarck's Welfare State". Current History. XVIII: 1–7.

- ↑ Smith, Munroe (December 1901). "Four German Jurists. IV". Political Science Quarterly. The Academy of Political Science. 16 (4): 669. doi:10.2307/2140421. ISSN 0032-3195. JSTOR 2140421.

- ↑ Megginson, William L.; Jeffry M. Netter (June 2001). "From State to Market: A Survey of Empirical Studies on Privatization" (PDF). Journal of Economic Literature. 39 (2): 321–89. doi:10.1257/jel.39.2.321. ISSN 0022-0515. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2005. .

- ↑ Disraeli, Benjamin. "Chapter 14". Sybil. Book 4 – via Project Gutenberg.

- ↑ Alexander. Medievalism. pp. xxiv–xxv, 62, 93, and passim.

- ↑ Esping-Andersen, Gøsta (1999). Social Foundations of Postindustrial Economies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198742002.

- ↑ Rice, James Mahmud; Robert E. Goodin; Antti Parpo (September–December 2006). "The Temporal Welfare State: A Crossnational Comparison" (PDF). Journal of Public Policy. 26 (3): 195–228. doi:10.1017/S0143814X06000523. ISSN 0143-814X.

- ↑ Romila Thapar (2003). The Penguin History of Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. Penguin UK. p. 592. ISBN 9780141937427. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- 1 2 Thakur, Upendra (1989). Studies in Indian History Issue 35 of Chaukhambha oriental research studies. Chaukhamba Orientalia original from: the University of Virginia. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ Indian History. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. p. A-185. ISBN 9780071329231. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ Indian History. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. pp. A–184–185. ISBN 9780071329231.

- ↑ Kher, N. N.; Aggarwal, Jaideep. A Text Book of Social Sciences. Pitambar Publishing. pp. 45–46. ISBN 9788120914667 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Crone, Patricia (2005), Medieval Islamic Political Thought, Edinburgh University Press, pp. 308–09, ISBN 0748621946

- ↑ Hamid, Shadi (August 2003), "An Islamic Alternative? Equality, Redistributive Justice, and the Welfare State in the Caliphate of Umar", Renaissance: Monthly Islamic Journal, 13 (8), archived from the original on 1 September 2003 )

- ↑ Grandner, Margarete (1996). "Conservative Social Politics in Austria, 1880–1890". Austrian History Yearbook. 27: 77–107.

- 1 2 Paxton, Robert O. (25 April 2013). "Vichy Lives! – In a way". The New York Review of Books.

- ↑ Marwick, Arthur (1967). "The Labour Party and the Welfare State in Britain, 1900-1948". American Historical Review. 73 (2): 380–403 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Dutton, Paul V. (2002). Origins of the French welfare state: The struggle for social reform in France, 1914–1947 (PDF). Cambridge University Press – via newbooks-services.de.

- 1 2 3 "History of Pensions and Other Benefits in Australia". Year Book Australia, 1988. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 1988. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ Garton, Stephen (2008). "Health and welfare". The Dictionary of Sydney. Archived from the original on 15 August 2012. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- 1 2 Yeend, Peter (September 2000). "Welfare Review". Parliament of Australia. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ E. P. Hennock, The Origin of the Welfare State in England and Germany, 1850–1914: Social Policies Compared (2007)

- ↑ Hermann Beck, Origins of the Authoritarian Welfare State in Prussia, 1815–1870 (1995)

- ↑ Elaine Glovka Spencer, "Rules of the Ruhr: Leadership and Authority in German Big Business Before 1914," Business History Review: 53 (Spring 1979), 1:40–64.

- ↑ Ivo N. Lambi, "The Protectionist Interests of the German Iron and Steel Industry, 1873–1879," Journal of Economic History: 22 (March 1962): 1: 59–70.

- ↑ Richard J. Evans, The Third Reich in Power, 1933–1939, New York: The Penguin Press, 2005, p. 489

- ↑ Esping-Andersen, Gøsta (1996). Welfare States in Transition: National Adaptations in Global Economy. London: Sage Publications.

- ↑ Huber, Evelyne, & John D. Stephens (2012). Democracy and the Left. Social Policy and Inequality in Latin America. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Mesa-Lago, Carmelo (1994). Changing Social Security in Latin America. London: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- ↑ Carlos Barba Solano, Gerardo Ordoñez Barba, and Enrique Valencia Lomelí (eds.), Más Allá de la pobreza: regímenes de bienestar en Europa, Asia y América. Guadalajara: Universidad de Guadalajara, El Colegio de la Frontera Norte

- ↑ Martínez Franzoni, J (2008). "Welfare Regimes in Latin America: Capturing Constellations of Markets, Families, and Policies". Latin American Politics and Society, 50(2), 67–100

- ↑ Barba Solano, Carlos (2005). Paradigmas y regímenes de bienestar. Costa Rica: Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales

- ↑ Riesco, Manuel (2009). "Latin America: A New Developmental Welfare State Model in the Making?" International Journal of Social Welfare, 18, S22–S36, doi:

- ↑ Cruz-Martínez, Gibrán (2014). "Welfare State Development in Latin America and the Caribbean (1970s–2000s): Multidimensional Welfare Index, Its Methodology and Results". Social Indicators Research, 119(3), 1295–317, doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0549-7

- ↑ Segura-Ubiergo, Alex (2007). The Political Economy of the Welfare State in Latin America: Globalization, Democracy and Development. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 29–31

- ↑ "Saudi Arabia". Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, 2000. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor; US State Department. February 23, 2001. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- ↑ Social Services, Saudinf.com

- ↑ "The Kingdom Of Saudi Arabia - A Welfare State". mofa.gov.sa. Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia, London: Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Saudi Arabia. Archived from the original on 28 April 2007. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ↑ Khalaf, Sulayman; Hammoud, Hassan (1987). "The Emergence of the Oil Welfare State". Dialectical Anthropology. 12 (3): 343–57.

- ↑ Susanto, A. B.; Susanto, Patricia (2013). The Dragon Network: Inside Stories of the Most Successful Chinese Family Businesses. Wiley. p. 22. ISBN 9781118339381.

- ↑ Scott Kennedy (2011). Beyond the Middle Kingdom: Comparative Perspectives on China's Capitalist Transformation. Stanford U.P. p. 89. ISBN 9780804777674.

- ↑ Hasmath, R, ed. (2015). Inclusive Growth, Development and Welfare Policy: A Critical Assessment. New York and Oxford: Routledge.

- ↑ Huang, Xian (March 2013). "The Politics of Social Welfare Reform in Urban China: Social Welfare Preferences and Reform Policies". Journal of Chinese Political Science. 18 (1): 61–85.

- ↑ Fraser, Derek (1984). The evolution of the British welfare state: a history of social policy since the Industrial Revolution (2nd ed.). p. 233.

- ↑ Francis G. Castles; et al. (2010). The Oxford Handbook of the Welfare State. Oxford Handbooks Online. p. 67. ISBN 9780199579396 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Bentley Gilbert, "David Lloyd George: Land, the Budget, and Social Reform", American Historical Review: 81 (Dec 1976): 5: 1058–66. in JSTOR

- ↑ Derek Fraser, The evolution of the British welfare state: a history of social policy since the Industrial Revolution (1973).

- ↑ Jane Lewis, "The English Movement for Family Allowances, 1917–1945." Histoire sociale/Social History 11.22 (1978) pp. 441–59.

- ↑ John Macnicol, Movement for Family Allowances, 1918–45: A Study in Social Policy Development (1980).

- ↑ Pat Thane, Cassell's Companion to Twentieth Century Britain (2002) pp. 267–68.

- ↑ Beveridge, Power and Influence

- ↑ Baksi, Catherine (1 August 2014). "Praise legal aid; don't bury it". The Law Society Gazette. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ↑ "Bagehot: God in austerity Britain" The Economist, published 2011-12-10

- ↑ Pawel Zaleski Global Non-governmental Administrative System: Geosociology of the Third Sector, [in:] Gawin, Dariusz & Glinski, Piotr [ed.]: "Civil Society in the Making", IFiS Publishers, Warszawa 2006

- 1 2 Walter I. Trattner (2007). From Poor Law to Welfare State, 6th Edition: A History of Social Welfare in America. Free Press. p. 15. ISBN 9781416593188.

- ↑ Quoted in Thomas F. Gosset, Race: The History of an Idea in America (Oxford University Press, 1997 [1963]), p. 161.

- ↑ Lester Frank Ward, Forum XX, 1895, quoted in Henry Steel Commager's The American Mind: An Interpretation of American Thought and Character Since the 1880s (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1950), p. 210.

- ↑ Henry Steele Commager, Editor, Lester Ward and the Welfare State (New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1967).

- ↑ Soeren Mattke; et al. (2011). Health and Well-Being in the Home: A Global Analysis of Needs, Expectations, and Priorities for Home Health Care Technology. Rand Corporation. pp. 33–. ISBN 9780833052797.

- ↑ Friedman, Gerald (June 2000). "The Political Economy of Early Southern Unionism: Race, Politics, and Labor in the South, 1880–1953". The Journal of Economic History published by Cambridge University Press, Vol. 60, No. 2, pp. 384–413. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ↑ John L. Campbell (2010). "Neoliberalism's penal and debtor states: A rejoinder to Loïc Wacquant". Theoretical Criminology. 14 (1): 68. doi:10.1177/1362480609352783.

- ↑ Loïc Wacquant. Prisons of Poverty. University of Minnesota Press (2009). p. 55 ISBN 0816639019.

- ↑ Richard Mora and Mary Christianakis. "Feeding the School-to-Prison Pipeline: The Convergence of Neoliberalism, Conservativism, and Penal Populism". Journal of Educational Controversy. Woodring College of Education, Western Washington University. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ↑ Haymes, Stephen N.; de Haymes, María V.; Miller, Reuben J., eds. (2015). The Routledge Handbook of Poverty in the United States. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978 0 41 567344 0.

- ↑ Bo Rothstein, Just Institutions Matter: The Moral and Political Logic of the Universal Welfare State (Cambridge, 1998), pp. 18–27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ferragina, Emanuele; Seeleib-Kaiser, Martin (2011). "Welfare regime debate: past, present, futures". Policy & Politics. 39 (4).

- ↑ Stephens (1979); Korpi (1983); Van Kersbergen (1995); Vrooman (2012)

- ↑ Esping-Andersen (1985).

- ↑ Esping-Andersen (1990), p. 71.

- ↑ According to the French sociologist Georges Menahem, Esping-Andersen's "decommodification index" aggregates both qualitative and quantitative variables for "sets of dimensions" which fluid, and pertain to three very different areas. These characters involve similar limits of the validity of the index and of its potential for replication. Cf. Georges Menahem, « The decommodified security ratio: A tool for assessing European social protection systems », in International Social Security Review, Volume 60, Issue 4, pp. 69–103, October–December 2007.

- ↑ Malnick, Edward (19 October 2013). "Benefits in Europe: country by country". The Telegraph – via telegraph.co.uk.

- ↑ Bo Rothstein, Just Institutions Matter: the Moral and Political Logic of the Universal Welfare State (Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp. 18–27.

- ↑ Kenworthy, Lane (2014). Social Democratic America. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199322511 p. 9.

- ↑ Ferragina, E.; et al. (2015). "The Four Worlds of 'Welfare Reality'". Social Risks and Outcomes in Europe, Social Policy and Society. 14 (2): 287–307 – via cambridge.org.

- ↑ Radcliff, Benjamin (2013). The Political Economy of Human Happiness. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- 1 2 Kenworthy, L. (1999). Do social-welfare policies reduce poverty? A cross-national assessment Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine.. Social Forces: 77: 3: 1119–39.

- 1 2 Bradley, D., Huber, E., Moller, S., Nielson, F. & Stephens, J. D. (2003) "Determinants of relative poverty in advanced capitalist democracies". American Sociological Review 68:3: 22–51.

- ↑ Atkinson, A. B. (1995). Incomes and the Welfare State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521557968.

- ↑ Lindert, Peter (2004). Growing Public: Social Spending And Economic Growth Since The Eighteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521821754.

- ↑ Martin Eierman, "The Myth of the Exploding Welfare State", The European, October 24, 2012.

- ↑ Does a generous welfare state crowd out student achievement? Panel data evidence from international student tests.

- ↑ Shepherd, Jessica (7 December 2010). "World education rankings: which country does best at reading, maths and science?". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ↑ http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=SOCX_AGG

- ↑ For social expenditure figures.

- ↑ "GDP per capita, PPP (current international $)". World Bank. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- ↑ J. Bradford DeLong, "American Conservatism's Crisis of Ideas" (23 February 2013).

- ↑ Edwards, James Rolph (2007). "The Costs of Public Income Redistribution and Private Charity" (PDF). Journal of Libertarian Studies. Mises Institute. 21 (2): 3–20 – via mises.org.

- ↑ Marx, Karl (1850). Address of the Central Committee to the Communist League. Retrieved 5 January 2013 – via Marxists.org.

- ↑ Bernstein, Eduard (April 1897). "Karl Marx and Social Reform". Progressive Review (7).

- ↑ Ryan, Alan (2012). The Making of Modern Liberalism. Princeton and Oxford University Presses. pp. 26 and passim.

- ↑ Ryan, Alan (2012). On Politics, Book Two: A History of Political Thought From Hobbes to the Present. Liveright. pp. 904−05.

- ↑ Taylor, Matt (February 22, 2017). "One Recipe for a More Equal World: Mass Death". Vice. Retrieved April 9, 2017.

- Arts, Wil and Gelissen John; "Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism or More? A State-of-the-art report" Journal of European Social Policy: 2:2 (2002):137–58.

- Bartholomew, James (2015). The Welfare of Nations. Biteback. p. 448. ISBN 9781849548304.

- Francis G. Castles; et al. (2010). The Oxford Handbook of the Welfare State. Oxford Handbooks Online. p. 67.

- Esping-Andersen, Gosta; Politics against markets, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press (1985).

- Esping-Andersen, Gosta; "The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism", Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press (1990).

- Ferragina, E. et al. (2015) The Four Worlds of ‘Welfare Reality’ – Social Risks and Outcomes in Europe. Social Policy and Society, 14 (2), 287–307.

- Ferragina, Emanuele and Martin Seeleib-Kaiser, "Welfare Regime Debate: Past, Present, Futures?" Policy & Politics: 39 (2011): 4: 583–611.

- Kenworthy, Lane. Social Democratic America. Oxford University Press (2014). ISBN 0199322511

- Korpi, Walter; "The Democratic Class Struggle"; London: Routledge (1983).

- Koehler, Gabriele and Deepta Chopra; "Development and Welfare Policy in South Asia"; London: Routledge (2014).

- Kuhnle, Stein. "The Scandinavian Welfare State in the 1990s: Challenged but Viable." West European Politics (2000) 23#2 pp. 209–28

- Kuhnle, Stein. Survival of the European Welfare State 2000 Routledge ISBN 041521291X

- Rothstein, Bo. Just institutions matter: the moral and political logic of the universal welfare state (Cambridge University Press, 1998)

- Radcliff, Benjamin (2013) The Political Economy of Human Happiness (New York: Cambridge University Press).

- Rachel Reeves, Rachel, and Martin McIvor. "Clement Attlee and the foundations of the British welfare state." Renewal: a Journal of Labour Politics 22#3/4 (2014): 42+. online

- Tanner, Michael (2008). "Welfare State". In Hamowy, Ronald. The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; Cato Institute. pp. 540–42. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n327. ISBN 9781412965804. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- Van Kersbergen, K. "Social Capitalism"; London: Routledge (1995).

- Vrooman, J.C. "Regimes and Cultures of Social Security: Comparing Institutional Models through Nonlinear PCA"; International Journal of Comparative Sociology:, 53: 5–6 (2012): 444–77.

External links

![]()

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Welfare state |

- An introduction to social policy, Robert Gordon University

- Social Security Programs Throughout the World, SSA.gov

- Race and Welfare in the United States, Bryn Mawr College

- Calvo, García. Analysis of Welfare Society

- Shavell's criticism of social justice programmes

- Principles of Fairness versus Human Welfare: On the Evaluation of Legal Policy

- Journal containing free daily information on welfare policies at local, national and EU level

- Radcliff, Benjamin (25 September 2013). "Western nations with social safety net happier".

- "Widefare: Asia's Emerging Welfare States Spread Themselves Thinly". The Economist: Asia. 6 July 2013.

- Lee Hyo-sik (12 February 2010). "Korea Next to Last in Social Welfare Spending". The Korea Times.

- Nadasen, Premilla (Winter 2016). "How a Democrat Killed Welfare". Jacobin.

Data and statistics

- OECD

- The impact of benefit and tax uprating on incomes and poverty

- Contains information on social security developments in various EC member states from 1957 to 1978

- Contains information on social security developments in various EC member states from 1979 to 1989

- Contains information on social assistance programmes in various EC member states in 1993

- Contains detailed information on the welfare systems in the former Yugoslav republics

| Library resources about Welfare state |