Queens–Midtown Tunnel

Logo of the Queens–Midtown Tunnel | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Official name | Queens Midtown Tunnel |

| Other name(s) | Midtown Tunnel |

| Location | Manhattan and Queens, New York City, New York, US |

| Coordinates | 40°44′44″N 73°57′53″W / 40.74556°N 73.96472°W |

| Route |

|

| Crosses | East River |

| Operation | |

| Opened | November 15, 1940 |

| Operator | MTA Bridges and Tunnels |

| Traffic | 73,470 (2016)[1] |

| Toll |

|

| Technical | |

| Length |

6,414 feet (1,955 m) (northern tube) 6,272 feet (1,912 m) (southern tube) |

| No. of lanes | 4 |

| Tunnel clearance | 12 feet 1 inch (3.68 m) |

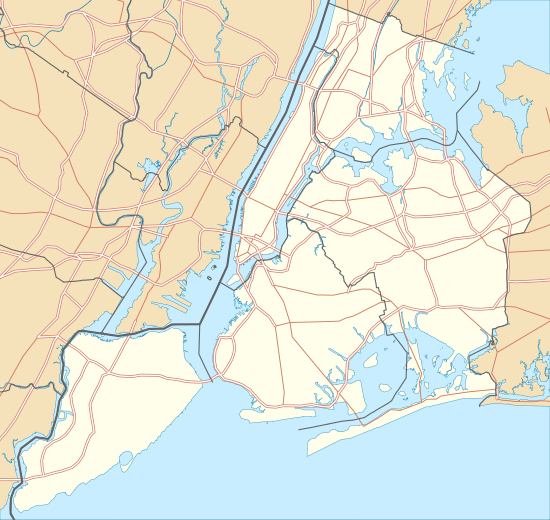

| Route map | |

| |

The Queens–Midtown Tunnel (also sometimes called the Midtown Tunnel)[2][3] is a vehicular tunnel under the East River connecting the New York City boroughs of Manhattan and Queens. The west end of the tunnel is located in the East Side of Midtown Manhattan; it is also the western terminus of Interstate 495, the highway of which the tunnel is designated. The east end of the tunnel is located in Long Island City in Queens, where I-495 continues eastbound across Long Island. The tunnel is maintained by MTA Bridges and Tunnels.

The Queens–Midtown Tunnel was first planned in 1921. Over the following years, the plans for the tunnel were modified, and by the 1930s, the tunnel was being proposed as the Triborough Tunnel, a tunnel connecting Queens and Brooklyn with both the east and west sides of Manhattan. The New York City Tunnel Authority finally started construction on the tunnel in 1936, although by then, the plans had been downsized. The tunnel, designed by Ole Singstad, was opened to traffic on November 15, 1940.

The Queens–Midtown Tunnel is owned by New York City and operated by MTA Bridges and Tunnels, an affiliate agency of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. It is used by several dozen express bus routes. Formerly, the tunnel also hosted the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus Animal Walk.

Description

The Queens–Midtown Tunnel consists of twin tubes each carrying two traffic lanes. The southern tube normally carries eastbound traffic to Queens, and the northern tube normally carries westbound traffic to Manhattan.[4] During the morning rush hour, the southern tube is converted to a bidirectional tube, with a single eastbound lane and a westbound high-occupancy vehicle lane, while the northern tube carries two westbound lanes. The 6,414-foot-long (1,955 m) northern tube is slightly longer than the 6,272-foot-long (1,912 m) southern tube because, although the tubes share the same tunnel portal in Queens, they surface at two different locations at Manhattan.[5]

Route

The Queens–Midtown Tunnel's eastern end is in Long Island City, where the Long Island Expressway transitions from an elevated viaduct to the tunnel structure. A toll plaza was formerly located at this location.[4] Exits 13 and 14 for the Long Island Expressway are located just east of the former toll plaza. Exit 13, located right underneath the Pulaski Bridge, contains an eastbound-only exit and entrance to and from Borden Avenue. Exit 14, at the same location, contains an eastbound exit and westbound entrance to the tunnel from New York State Route 25A (21st Street); there is no westbound exit, and the eastbound entrance is from Exit 13. Eastbound traffic entering from Exit 13 intersects with traffic exiting to Exit 14, which must stop and yield to each other. Westbound traffic entering from Exit 14 can enter the tunnel from either 21st Street or 50th Avenue.[4][6] Although exits 13 and 14 are part of I-495's sequential exit-numbering system (as opposed to a mileage-based system), they are actually the first and second exits on I-495; the exits from the Manhattan side are not numbered.[4]

The tunnel travels under the East River and aligns under 42nd Street on the Manhattan side, then curves south under First Avenue and then west at 38th Street. Its western end is in Midtown Manhattan between 36th and 37th Streets, east of Second Avenue.[4]

Both tubes surface east of Second Avenue. The westbound roadway of the northern tube passes underneath Second Avenue, continuing west for half ablock splitting between Second and Third Avenues, where three exit ramps split. One ramp continues westbound to 37th Street, while two more extend south to 34th Street and north to 41st Street along Tunnel Exit Street.[4] The northernmost block of Tunnel Exit Street, between 40th and 41st Streets, was sold to private interests in 1961 but continues to be in public use.[7] The southern tube immediately rises to ground level, as it is fed directly by eastbound traffic on 36th Street, as well as from entrance ramps east of Second Avenue. These entrance ramps, collectively referred to as Tunnel Entrance Street, run between Second and First Avenues and continue south to 34th Street and north to 40th Street.[4][8] Electronic toll gantries are located just outside the Manhattan portals.[9]

Originally, the Manhattan side was also supposed to contain connections to the proposed Mid-Manhattan Expressway and to the East River (FDR) Drive, but neither were built.[8][10] The Queens side was to have connected to an expressway that would have reached to the Rockaway Peninsula.[11]

The tunnel was once designated as part of New York State Route 24. In the mid-1940s, NY 24 was routed to follow the Crosstown Connecting Highway (now the right-of-way of I-278) and Midtown Highway (now the Long Island Expressway, or I-495) to the Queens–Midtown Tunnel. It then continued through the tunnel to end at NY 1A in Manhattan.[12][13] The Crosstown Connection Highway and the Midtown Highway were upgraded into the first portions of the Brooklyn–Queens Expressway (BQE) and the Queens Midtown Expressway, respectively, in the early 1950s. At the time, the Queens Midtown Expressway ended at 61st Street.[14][15] NY 24 was rerouted along the LIE between the Queens–Midtown Tunnel and Farmingdale, New York, in the late 1950s,[16][17] and the designation was removed from the LIE altogether c. 1962.[18][19] The LIE and Queens–Midtown Tunnel gained their I-495 designation by around 1960.[17][18]

Features

As planned, the two tubes would have had an exterior diameter of 31 feet (9.4 m), a roadway 21 feet (6.4 m) wide, and a maximum vehicular height limit of 13 feet 1 inch (3.99 m).[20] As of 2015, the vehicular height limit is 12 feet 1 inch (3.68 m), and the width limit is 8 feet 6 inches (2.59 m).[21]

The tunnel contains two ventilation buildings, both 100-foot-tall (30 m) orange brick structures in the Art Deco style.[22][23] One is located on the Manhattan side, on a city-owned block bounded by 41st and 42nd Streets, First Avenue, and the FDR Drive. The building is octagon-shaped. This block is shared with the Robert Moses Playground, a playground operated by the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation (NYC Parks). The playground was built along with the tunnel and opened in 1941.[24][25] The other ventilation building is located on the Queens side, in the center of Borden Avenue between Second and Fifth Streets.[26][27] This structure is rectangular, unlike its Manhattan counterpart, and due to its location in the middle of Borden Avenue, traffic along the road drives around the building.[22] The two buildings originally contained a combined 23 fans, which were replaced in the mid-2000s. The ventilation system is capable of completely filtering the tubes' air within 90 seconds.[28][29]

The Queens portal also contains a small park, "Bridge and Tunnel Park", containing one court for basketball and two for handball. It is bounded by the Pulaski Bridge on the west, 50th Avenue on the north, 11th Place on the east, and the Queens–Midtown Tunnel entrance ramp on the south. The park opened in 1979, and is operated by the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority (TBTA; now MTA Bridges and Tunnels). However, NYC Parks owns the land that constitutes Bridge and Tunnel Park.[30]

History

Initial proposal

The Queens–Midtown Tunnel was originally proposed in 1921 by Manhattan's borough president, Julius Miller.[31] It gained serious traction in 1926, under the name Triborough Tunnel or 38th Street Tunnel. Miller, in conjunction with Queens' borough president, Maurice E. Connolly, proposed the $58 million tunnel as a way to connect Midtown Manhattan with Long Island City in Queens as well as Greenpoint in Brooklyn. At the time, there was frequent and heavy congestion on bridges across the East River, which separated Queens and Brooklyn (both on Long Island) from the island of Manhattan.[32][33] Brooklyn's borough president, James J. Byrne, was not happy that the Queens and Manhattan borough presidents had proposed the Triborough Tunnel without consulting him first.[34][35] In December 1926, Mayor James J. Walker formed a commission to study traffic congestion on New York City bridges and tunnels.[34] Local civic groups felt that it would be inadequate to simply increase capacity on existing crossings like the Queensboro Bridge, since there were no connections whatsoever between Long Island and Midtown Manhattan.[36] The city declined to give its immediate support to the Triborough Tunnel proposal.[37]

In April 1927, civic groups formed the 38th Street Tunnel Committee to advocate for the tunnel.[38] They stated that the tunnel would act as a relief corridor for traffic from midtown Manhattan, since at the time, all of the vehicular crossings from Manhattan Island were located to either the north or the south of midtown.[39][40] That June, the city voted to allocate $100,000 toward surveying sites and making test bores.[41][42] Several more civic groups expressed support for the tunnel and urged that it be completed as soon as possible.[43] This number had grown to 35 civic groups by February 1929.[44]

In May 1928, civic groups proposed an entire series of underground tunnels under Manhattan, connecting Queens and Long Island in the east with Weehawken, New Jersey, in the west. Whereas the Queens–Midtown Tunnel would cross the East River and connect Queens to the East Side of Manhattan, the Midtown Hudson (Lincoln) Tunnel would cross the Hudson River and connect the West Side of Manhattan to New Jersey.[45] This planned tunnel would run from 10th Avenue on Manhattan's west side, running underneath Manhattan streets and the East River, and surface near Borden Avenue at the Long Island City side. A spur from Manhattan would diverge to Oakland Street in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, and the tunnel would also have an entrance and exit to Third Avenue in Manhattan.[41][46] The tunnels' route lengths would total approximately 4.3 miles (6.9 km); the segments of the tunnel under the East River, under Manhattan, and between Queens and Brooklyn would each comprise about a third of the tunnel's length.[47] The Fifth Avenue Association further proposed that the city create a bridge-and-tunnel authority that would raise funding and oversee construction and operations, in a format similar to the Port of New York Authority, which was already serving such a purpose for Hudson River crossings.[48]

Approval

The Chamber of Commerce of the State of New York formally endorsed the Manhattan-to-Queens crossing project in January 1929, but stated that it was open to the construction of either a bridge or a tunnel.[49] The city then began conducting a study on the feasibility of constructing the Triborough Tunnel, as well as a Triborough Bridge between Queens, Manhattan, and the Bronx.[50] The results of that study were released in May, in which it was suggested that the city construct a network of parkways and expressways, including a major highway leading from Long Island to the Manhattan-Queens tunnel.[51] The Queens Planning Commission also recommended the construction of the Triborough Tunnel.[52] Official plans for the Triborough Tunnel were released that June; the $86 million project was proposed to contain a series of feeder highways, including the crosstown Manhattan tunnel and the tunnel spur from Brooklyn.[53] The tunnel would charge tolls to pay for maintenance and create revenue for the city.[54] With the passage of the toll provision, officials expected that tunnel construction could start as soon as the end of that year.[55]

However, in July 1929, the city was faced with unexpected legal issues: the language of Walker's proclamation, which ostensibly allowed construction to proceed, had in fact restricted the construction of the tunnel to the wrong city agency.[56] Civic groups convened a special session in which they asked the New York City Board of Estimate to override the laws so the tunnel could be approved.[57] The Board of Estimate ultimately voted to grant $5 million to feasibility studies and preliminary construction for two tunnels: the Manhattan-Queens tunnel, as well as another tunnel under the Narrows between Brooklyn and Staten Island.[58] Afterward, the New York City Board of Transportation hurried to submit plans for the construction of the Triborough Tunnel.[59]

Further logistical issues arose in January 1930, after the Midtown Hudson Tunnel between Manhattan and New Jersey had been approved, and engineers discussed how the Triborough Tunnel would connect with the Hudson River tunnel.[60] Around this time, engineers revised the approaches from the Long Island side. Whereas the original plans had called for a tunnel under Newtown Creek to Brooklyn, which would parallel 11th Street in Queens, the new plans called for a tunnel to Brooklyn that ran diagonally to 21st Street (one block east of 11th Street), which would connect to a viaduct that flew over East River Railroad Tunnels' Queens portals before ending at Jackson Avenue in Long Island City.[61] Exploratory borings were reportedly completed by June 1930, and engineers were finalizing the plans.[62] In September 1930, the Board of Transportation slightly modified the plan for the tunnel, this time within Manhattan. The tubes would surface at plazas at Second Avenue in Manhattan before descending again until Tenth Avenue. The eastbound and westbound tunnels would respectively run under 37th and 38th Streets, since the streets were too narrow to accommodate two tubes side-by-side.[63] Advocates of the Triborough Tunnel opposed the construction of surface-level exit plazas, saying that motorists from either of the tunnel's ends would have to briefly drive along the street before continuing their trip.[64] One group proposed a crosstown elevated highway in lieu of a tunnel under Manhattan.[65]

By the end of that year, the United States Department of War had approved of the construction of the Triborough Tunnel, since the tube would not hinder maritime navigation during wartime.[66][67] However, by then, the Board of Transportation had delayed construction for a few months because of significant public concerns about the crosstown-highway section.[67] In June 1931, the Board of Transportation submitted a detailed revised plan for the Triborough Tunnel to the Board of Estimate for a vote. The project was now expected to cost $93.6 million, including a $23.5 million initial phase under the East River and within Queens.[68] That October, the Board of Estimate allocated $200,000 for planning, with construction expected to start in March 1932 and completion of the East River by 1936.[69] However, by July 1932, no contracts had been awarded yet due to a lack of funds, and the Triborough Tunnel project was estimated to cost $80 million.[70][71] As the Midtown Tunnel plan faltered, the Board of Estimate approved the construction of other projects that had not been as extensively studied.[72]

Plans revived

Plans for the tunnel were finally revived in May 1935, when Governor Herbert H. Lehman signed a bill to set up the Queens–Midtown Tunnel Authority, which would build the tunnel.[73] Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia subsequently nominated three prominent businessmen to head the agency.[74] La Guardia supported the immediate construction of the tunnel because he believed it would help traffic get to the 1939 New York World's Fair.[75] The Queens–Midtown Tunnel Authority applied for a federal loan and grant, worth a combined $58.4 million, from the Public Works Administration (PWA) that September.[76] Two months later, the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) offered to lend $47.1 million of the tunnel's cost on the condition that the PWA grant the remaining $11.3 million balance.[77] In response to the RFC's offer, PWA chairman Harold L. Ickes stated that his agency had $32.7 million readily available for the construction of the tunnel.[78] The tunnel's projected $58.4 million cost only applied to the 3,790-foot (1,160 m) section of the tunnel under the river, as well as the 1,600-foot (490 m) Queens approach and the 2,400-foot (730 m) Manhattan approach to the Second Avenue exit and entrance plazas.[20][77] The Brooklyn spur had been canceled for the time being because it could not self-fund itself, while the crosstown highway was to be included in a later project.[79] Civic groups continued to advocate for the canceled Brooklyn spur, even after construction started.[80]

The federal government made a tentative allotment of $58.3 million toward the Queens–Midtown Tunnel in January 1936, consisting of the RFC loan and PWA grant. The grant was expected to be paid off using toll revenue and the sale of $50 million in bonds.[20] Also in January 1936, the New York State Legislature organized the New York City Tunnel Authority to construct the Queens-Midtown and Brooklyn–Battery Tunnels.[81] The plans for the tunnel had been completed to the extent that tunnel construction could start as soon as the city received the federal funds.[82][83] The Tunnel Authority accepted the grant in a March 1936 ceremony.[84] With the approval of that grant, the Queens–Midtown Tunnel became the United States' largest public works project that was not supervised by a federal agency.[85][86][31]

In April 1936, Manhattan borough president Samuel Levy proposed a six-lane bridge, in lieu of the Queens–Midtown Tunnel, because he believed a bridge would save an estimated $36 million.[87] This plan was endorsed by Brooklyn borough president Raymond V. Ingersoll[88] and State Senator Thomas C. Desmond.[89] Robert Moses, the chairman of the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority (TBTA), also supported a bridge, but for a separate reason: he held a grudge against the Tunnel Authority because he had been rejected from running the authority. Moses's agency would be the only entity who could construct and operate a toll bridge entirely within the New York City limits, and the already-approved federal funding for the tunnel would be canceled if he delayed the tunnel project for long enough.[90]:608–609 New York City Tunnel Authority commissioner William Friedman opposed the bridge because the PWA funding had been secured already.[87] The Queens Borough Chamber of Commerce also opposed the bridge, as did Mayor La Guardia.[91][92] The PWA, for its part, ordered that tunnel planning work proceed, regardless of the status of the bridge plans.[93] A bill for the proposed bridge was voted down in the New York State Senate that May.[94][90]:609

Construction

The Tunnel Authority approved plans for the tunnel in August 1936.[95] The Authority's chief engineer, Ole Singstad, was tasked with designing the tunnel.[10][8] By the end of the month, the first bids for the tunnel were advertised.[96] A groundbreaking ceremony for the tunnel was held on the Queens side on October 1, 1936, with President Franklin D. Roosevelt in attendance. Shortly afterward, the New York City Tunnel Authority awarded the first contracts for the tunnel's construction.[97][98][99] Test bores for the tubes were started later that month.[100] These exploratory bores utilized diamond-tipped drills, which were operated from flat-bottomed boats and drilled vertically downward into the riverbed.[101][5]

By November 1936, the test bores had been completed, and engineers determined that many geological and manmade obstacles made it difficult to build the tunnel. For one thing, the Queens–Midtown Tunnel's path passed through a large concentration of solid rock, although there were also some pockets of dirt under the river that would be easy to dig through. Additionally, workers had to take care to not accidentally damage the East River railroad tunnels to the south and the Steinway Tunnel to the north when digging. Four shafts, consisting of one construction and one ventilation shaft on each side, were to be part of the tunnel's construction, but by November 1936, only the Queens construction shaft had been built.[102][103] The next month, the Tunnel Authority, which had accepted a bid for the Midtown ventilation shaft, was authorized to begin construction immediately on the shaft, which was located on the block between 41st and 42nd Streets, First Avenue, and the East River Drive.[104] Construction on the Manhattan ventilation shaft began with a ceremony on December 31, 1936,[105] and the city bought the block outright in April 1937.[106]

The first $500,000 allocation of PWA funding was released in January 1937.[107] A 40-foot-deep (12 m) layer of clay was placed along the tunnel's path at the bottom of the East River to prevent air leakages and maintain air pressure within the tubes.[108] This "blanket" contained about 250,000 cubic yards (190,000 m3) of clay.[109] A clay blanket had not been used in any prior underwater tunnel projects. As a result, digging work was delayed for four months to allow the clay layer to be placed, and officials feared that the tunnel might not open before the end of 1940, as was originally planned.[110] A contract for digging the tubes themselves was awarded in June 1937.[111][86] The project employed as many as 2,500 sandhogs at a time. Because the work site had such a high air pressure, each man worked two 30-minute shifts per day, punctuated by a 6-hour break in a depressurized chamber so that they would not get decompression sickness.[112][113]

On the Queens side, it was proposed to link the tunnel to a new expressway (now part of the Long Island Expressway).[114] Eventually, officials agreed to construct the 2.5-mile (4.0 km) link to what is now the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, forming part of a longer highway that connected directly to LaGuardia Airport.[115] However, the status a corresponding limited-access expressway on the Manhattan side, connecting to the Lincoln Tunnel, was still undecided.[116] The Manhattan entrance and exit ramps replaced the St. Gabriel Church, which later relocated to Park Avenue.[117] By early 1938, costs were rising quickly, and only 65% of the contracts had been awarded. Tunnel Authority Commissioner Friedman stated that if costs were to keep increasing at the same rate, construction might have to be abandoned midway through.[118] By September 1938, three-fourths of the tunnel's contracts had been awarded.[119]

Work on the underwater section of the tubes started in April 1938.[120][85] Underwater boring was supposed to have started earlier but the geology of the underwater section had delayed construction.[121] When the underwater digging started, La Guardia opened the valves that allowed compressed air to flow into the tubes, and workers started digging the tunnels under the river from each end.[120][85] The pressurized air allowed sandhogs to work as much as six hours per day in two 3-hour shifts, but as they tunneled nearer to the center of the river, the pressure increased and sandhogs worked fewer hours per day.[122] Builders also pumped air along the top of the tunnel to prevent water from seeping in.[109] Later, workers began wearing oxygen masks connected to a portable machine that gave out pure oxygen.[123] Despite the precautions taken to avoid sudden depressurization of the tubes, about 300 cases of decompression sickness were recorded during the construction process.[5]

The project was about 25% completed by September 1938.[124] Workers primarily dug underwater using tunnelling shields on either side of each tube, but significant amounts of dynamite were also used when trying to dig through particularly thick sheets of rock. Afterward, steel rings, each composed of 14 sections which individually weighed up to 3,500 pounds (1,600 kg), were laid within the tunnel.[109][5] In March 1939, the PWA released a report predicting that the tunnel would not be complete until summer 1941, eight months later than originally planned, due to geological difficulties.[125] Around the same time, Robert Moses alleged that the Queens–Midtown Tunnel would not be profitable, during an unrelated argument about the feasibility of building the Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel.[126] This prompted the New York State Legislature to conduct an investigation into the Queens–Midtown Tunnel's costs.[127] Moses's allegation also originated from his resentment toward the Tunnel Authority.[90]:698

Work proceeded quickly afterward, and the tunnel was 60% complete by May 1939.[128] Construction was briefly halted in July when sandhogs went on strike for two weeks due to a disagreement between two unions.[129] By that time, the two ends of the tubes were only separated by 850 feet (260 m). Workers digging from the Manhattan side no longer required compressed air because the tubes had reached a rock cropping.[130][131] With so little distance to go until the tubes were connected, the sandhogs sped up their pace of digging.[132] By late September, the project was 45 days ahead of schedule and employing 3,200 workers.[133]

Both tubes were connected with a "holing through" ceremony in November 1939, with a margin of error of less than 0.5 inches (13 mm).[134][135] In January 1940, another construction milestone was reached when the last of 1,622 metal rings were installed in the tubes.[136] The ventilation buildings were almost completed,[23] and property at the Queens portal was being demolished to make way for the tunnel approaches.[137] By May 1940, only three contracts remained to be awarded, and the tunnel was 90% complete.[138]

Opening and early years

The Queens–Midtown Tunnel finished on time in fall 1940.[139] Roosevelt was the first person to drive through the tunnel, on October 28, 1940.[140][99] However, the rest of the public was not to use it until mid-November.[141] An advertisement for the tunnel, published in newspapers just before its opening, touted it as "the toll that isn't a toll" with the slogan "Cross In 3 Minutes, Save In 3 Ways ... Time! Money! Gas!"[142] The Queens Chamber of Commerce's president praised the Queens–Midtown Tunnel as something that would spur development in Queens.[143]

The tunnel was opened to traffic on November 15, 1940, with a ceremony on the Queens side. The attendees included the Queens and Manhattan borough presidents; U.S. Senator Robert F. Wagner; and New York City Council president Newbold Morris, who was attending in La Guardia's stead.[31][144] The tubes were fitted with a then-new lighting technology that allowed drivers to more quickly adjust to the sunlight upon leaving the tunnel.[145] One hundred and fifty workers were hired and trained to operate the tunnel.[146] Twelve female workers would also be hired in 1943 due to a shortage of male guards.[147]

In a report published in August 1939, the New York City Tunnel Authority had estimated that the tunnel would carry 10 million vehicles in its first year and would reach its 16-million annual-vehicle capacity by 1952.[148] However, in the Queens–Midtown Tunnel's first few months, traffic counts were lower than expected because motorists could use the East River bridges to the north and south for free.[149] The tunnel had carried one million vehicles by February 1941, three months after opening.[150] This was further exacerbated by the gasoline rationing during World War II, which caused vehicular trips in general to decline.[151] The tunnel was closed during the nighttime beginning in February 1943, but due to growing nighttime traffic demand, 24-hour operation resumed in July 1944.[152] By 1946, the tunnel was running a $5.8 million deficit.[153] The Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, which had succeeded the New York City Tunnel Authority, recorded a 72% increase in tunnel traffic in the first half of that year, compared to the same time frame during the previous year.[154] The tunnel recorded its first profits in 1949, with a net earning of $659,505.[155][156][90]:698

In 1950, the TBTA and several airlines agreed to build the East Side Airlines Terminal on the Manhattan side of the tunnel, after having negotiated about such a terminal for four years.[157][158] The terminal, a stone-faced building, opened in 1953, along First Avenue between 37th and 38th Street. The terminal hosted bus routes that would take passengers to either LaGuardia or John F. Kennedy International Airports.[159] The terminal operated until 1983, and it was sold in 1985.[160] This site is now occupied by The Corinthian, an apartment complex.[161]

Mid-Manhattan Expressway and third tube plan

Plans to connect the Queens-Midtown and Lincoln Tunnels resurfaced in 1950, but were dropped for lack of support.[162] In 1959, Robert Moses proposed adding a third tube to the Queens–Midtown Tunnel to relieve congestion.[163] The tube would be located to the south of the two existing tubes,[164] and at one point, officials proposed connecting the third tube's eastern end to Brooklyn.[165] In January 1965, Moses announced that money had been allocated to a feasibility study for the third tube, which was projected to cost $120 million. This proposal was part of his plan to build a Mid-Manhattan expressway over 30th Street.[164][166] The third tube would also connect to the ultimately unbuilt Bushwick Expressway, which would extend across northeastern Brooklyn and southwestern Queens to connect with the present-day Nassau Expressway.[167][168][169]

In December 1965, Moses canceled his plans for the Mid-Manhattan Expressway due to opposition from the city government. However, he affirmed that the TBTA would construct a third tube for the Queens–Midtown Tunnel because it did not require the city's approval, and that the new tube would be completed four-and-a-half years after construction started. He stated that after the third tube was completed, traffic in the Queens–Midtown Tunnel would be modeled after that of the three-tube Lincoln Tunnel, with two tubes dedicated exclusively to westbound and eastbound traffic as well as a reversible-flow center tube.[170] Although the Queens Chamber of Commerce supported the third-tube project,[171] citywide officials opposed it. Moses ignored the city's disapproval, and in March 1966, advertised for bids to make test borings for the third tube.[172][173] The TBTA continued studying the feasibility of a third tube through 1967.[174] Ultimately, a third tube was never built.

Later years

In 1971, one lane of the Queens–Midtown Tunnel's eastbound tube was converted to a westbound high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) and bus lane during the morning rush hours. The reversible tunnel lane was fed by a HOV/bus lane along the Long Island Expressway, which started 2 miles (3.2 km) east of the tunnel's Queens portal and only operated during the morning peak period.[175]

From 1981 to 2016, the tunnel was closed to traffic for a few hours one night each spring to allow for the annual "Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus Animal Walk". Several nights before the circus opened at Madison Square Garden, the elephants marched into Manhattan and down 34th Street to the arena.[176] The animals had formerly been transported into the city via the West Side Line in Manhattan, but the southernmost part of that line, the High Line viaduct, was closed in 1981 due to construction on the nearby Javits Center. The first "Animal Walk" through the Queens–Midtown Tunnel memorialized a similar event ten years earlier, when the animals had walked to Manhattan through the Lincoln Tunnel due to a railroad strike.[177] This event was a much-anticipated annual tradition for many members of the general public, and crowds of several hundred people would flock to the Queens–Midtown Tunnel's Queens portal to see the march in the middle of the night.[178] However, it also attracted protests from organizations who opposed what they saw as the inhumane treatment of the circus animals.[179] When the circus stopped using elephants in 2016, the elephant walk ceased.[180][181]

The tubes' roadways were originally paved with bricks. The road surface was replaced with asphalt in 1995.[5] Two years later, the TBTA's successor, MTA Bridges and Tunnels, announced its intention to renovate the roof of the Queens–Midtown Tunnel.[182] The $132 million project,[183] completed in May 2001, involved replacing the roof with 930 slabs of concrete that were suspended from brackets glued onto the tunnel shell.[184] The major contract for the renovation project, worth $97 million, received scrutiny when it was discovered that the contractor had given money to the political party of Governor George Pataki just before the contract was awarded. However, a state judge found that the MTA did not break any laws or ethical obligations when it awarded the contract to the Pataki donor instead of one of the other candidates for that contract.[185] In 2004, the MTA started to replace the 23 fans within the tunnel's ventilation structures.[29] This project was completed in 2008.[186]

For a short time after the September 11 attacks in 2001, all Manhattan-bound traffic through the tunnel was subject to a high-occupancy vehicle restriction.[187] This restriction was removed in April 2002.[188]

In 2017–2018, the tiled walls in the Queens–Midtown and Brooklyn–Battery Tunnels were replaced due to damage suffered during Hurricane Sandy in 2012. The re-tiled white walls have gold-and-blue stripes, representing the official state colors of New York. Controversy arose over the cost of re-tiling the tunnels, which cost a combined $30 million, because of the ongoing transit crisis at the time.[189]

Bus routes

The tunnel carries 21 express bus routes; sixteen of these routes use the tunnel for westbound travel only. The bus routes that use the tunnel are the BM5, QM1, QM2, QM3, QM4, QM5, QM6, QM7, QM8, QM10, QM11, QM12, QM15, QM16, QM17, QM18, QM24 and QM25, all operated by the MTA Bus Company, and the X63, X64 and X68, operated by MTA New York City Transit. All of these routes except the BM5, QM7, QM8, QM11 and QM25 use the tunnel for westbound travel only, as most of the routes use the Queensboro Bridge for eastbound travel.[190]

Tolls

As of March 19, 2017, drivers pay $8.50 per car or $3.50 per motorcycle for tolls by mail. E‑ZPass users with transponders issued by the New York E‑ZPass Customer Service Center pay $5.76 per car or $2.51 per motorcycle. All E-ZPass users with transponders not issued by the New York E-ZPass CSC will be required to pay Toll-by-mail rates.[191]

Open-road cashless tolling started on January 10, 2017.[9] The tollbooths were dismantled, and drivers are no longer able to pay cash at the tunnel. Instead, there are cameras mounted onto new overhead gantries located on the Manhattan side.[192][193] Drivers without E-ZPass have a picture of their license plate taken, and a bill for the toll is mailed to them. For E-ZPass users, sensors detect their transponders wirelessly.[192][193]

References

- ↑ "New York City Bridge Traffic Volumes" (PDF). New York City Department of Transportation. 2016. p. 11. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ↑ "Queens Midtown Tunnel". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- ↑ "Queens Midtown Tunnel Access Roads". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Google (April 16, 2018). "Queens Midtown Tunnel, New York, NY" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Salazar, Cristian (November 13, 2015). "The Queens Midtown Tunnel turns 75: See rare photos". am New York. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "Queens County Inventory Listing" (CSV). New York State Department of Transportation. August 7, 2015. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- ↑ Stengren, Bernard (May 1, 1960). "Midtown Tunnel Exit Strip Is Sold to Private Company; But Triborough Agency Retains Right to Use Road for Traffic Part of Midtown Tunnel Exit Road Sold". The New York Times. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Plans for Queens–Midtown Tunnel and How It Will Look" (PDF). Brooklyn Daily Eagle. August 16, 1936. pp. E5. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- 1 2 "Queens–Midtown Tunnel tolls go cashless". ABC7 New York. January 10, 2017. Retrieved February 16, 2018.

- 1 2 "CITY SOON TO BEGIN TUNNEL TO QUEENS". The New York Times. August 16, 1936. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "17-MILE HIGHWAY MAPPED IN QUEENS; Express Road From Midtown Tunnel to the Rockaways to Cost $20,000,000 SECTIONS TO BE ELEVATED Part Near Tube May Be Built by City as an Approach to the World's Fair WAGNER AIDS PROPOSAL PWA Loan and Grant Will Be Asked-Civic Bodies to Be Rallied for Thoroughfare An Artery to the Fair Jones Supports Plan". The New York Times. February 7, 1937. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ New York with Pictorial Guide (Map). Cartography by General Drafting. Esso. 1942.

- ↑ New York Road Map and Pictorial Sight-Seeing Guide (Map). Cartography by Rand McNally and Company. Sinclair Oil Corporation. 1947.

- ↑ New York (Map). Cartography by Rand McNally and Company. Sunoco. 1952.

- ↑ New York with Special Maps of Putnam–Rockland–Westchester Counties and Finger Lakes Region (Map) (1955–56 ed.). Cartography by General Drafting. Esso. 1954.

- ↑ New York with Special Maps of Putnam–Rockland–Westchester Counties and Finger Lakes Region (Map) (1958 ed.). Cartography by General Drafting. Esso. 1958.

- 1 2 New York and New Jersey Tourgide Map (Map). Cartography by Rand McNally and Company. Gulf Oil Company. 1960.

- 1 2 New York and Metropolitan New York (Map) (1961–62 ed.). Cartography by H.M. Gousha Company. Sunoco. 1961.

- ↑ New York with Sight-Seeing Guide (Map). Cartography by General Drafting. Esso. 1962.

- 1 2 3 "ICKES ALLOTS CITY $58,365,000 TO BUILD EAST RIVER TUNNEL; Roosevelt Approves Big Grant Contingent Upon Change in Enabling Law". The New York Times. January 3, 1936. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "New York City Truck Route Map" (PDF). nyc.gov. New York City Department of Transportation. June 8, 2015. Retrieved September 12, 2017.

- 1 2 "Keeping Things Fresh At Queens Midtown Tunnel". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. October 27, 2014. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- 1 2 "NEW TUBE GETTING VENTILATION UNITS; Two 100-Foot Buildings for Tunnel Nearly Ready in Manhattan and Queens". The New York Times. February 13, 1940. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Robert Moses Playground Highlights". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ↑ "St. Vartan Park Highlights". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. Retrieved August 20, 2011.

- ↑ "Chapter 2: Land Use, Zoning, and Public Policy". Hunter's Point South Rezoning and Related Actions FEIS (PDF). New York City Economic Development Corporation. April 3, 2008. p. 5. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "Chapter 7: Historic Resources". Hunter's Point South Rezoning and Related Actions FEIS (PDF). New York City Economic Development Corporation. April 3, 2008. p. 7. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "Queens Midtown Tunnel Turns 70 Today". WNYC. February 26, 2009. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- 1 2 "FAN-TASTIC MAKEOVER FOR TUNNEL". New York Post. July 12, 2004. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "Bridge and Tunnel Park Highlights : NYC Parks". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "$58,000,000 Tunnel to Queens Opened". The New York Times. November 16, 1940. p. 1. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- ↑ "Demands Quick Traffic Relief For Jamaica" (PDF). Long Island Daily Press. December 20, 1926. p. 2. Retrieved April 16, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "VEHICLE TUBE PLAN FOR QUEENS IS READY; Miller Will Submit $58,000,000 Project for Approval of the Estimate Board Tomorrow. ENABLING ACT DRAWN ALSO Realty Levy to Pay Part of Cost Provided -- Tunnel Would Link Three Boroughs". The New York Times. December 8, 1926. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- 1 2 "ASKS STUDY OF JAMS ON EAST RIVER BRIDGES; Board of Estimate Wants Mayor to Name Committee to Report on McKee's Charges". The New York Times. December 10, 1926. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ↑ "Triboro Tunnel for Vehicles is Moved by Miller" (PDF). Brooklyn Daily Eagle. December 9, 1926. p. 3. Retrieved April 16, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "Real Estate Men Urge Mobilization for Traffic Relief" (PDF). Greenpoint Daily Star. December 24, 1926. p. 3. Retrieved April 16, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "CITY HEADS DEFER QUEENS TUBE PLAN; Advice Miller to Seek State Aid for Vehicular Tunnel Under East River. FOR PROJECT IN PRINCIPLE Mayor Confuses". The New York Times. January 4, 1927. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ↑ "BUSINESS MEN WANT EAST RIVER TUNNEL; Organize Movement to". The New York Times. April 15, 1927. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ↑ "VEHICULAR TUBE TO L. I. IS DEMANDED" (PDF). Long Island Daily Press. April 19, 1927. p. 1. Retrieved April 16, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "SEE TRAFFIC RELIEF IN EAST RIVER TUBE; Backers of Long Island City Tunnel Say It Would Reduce Jam Here. TEN REASONS ARE OUTLINED Advocates Declare Congestion on Bridge and in 3 Boroughs Could Be Reduced. HEARING NEXT MONDAY Proposed Vehicular Tube From 38th Street Will Be Discussed Before Estimate Board". The New York Times. April 19, 1927. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- 1 2 "REAL ESTATE BOARD HEARS OF PLANS FOR VEHICULAR ARTERIES" (PDF). Long Island Daily Press. June 16, 1927. p. 10. Retrieved April 16, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "CITY VOTES FUNDS FOR QUEENS TUNNEL; Appropriates $100,000 for Survey and Borings of 38th Street Tube. MAYOR EXPLAINS ACTION Hopes Laws Will Be Passed to Permit Financing by a Private Bond Issue". The New York Times. June 10, 1927. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑

- "MERCHANTS FAVOR TUNNEL TO QUEENS; East Thirty-eighth Street Tube Would Increase Accessibility of District, They Say. TRAFFIC PROBLEM ACUTE Congestion Said to Cost Manhattan Thousands of Dollars Every Day". The New York Times. June 26, 1927. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- "SEEKS LAW TO PUSH 38TH STREET TUNNEL; Capt. Pedrick Says Proposed Tube Is Vitally Necessary for the Whole City. WOULD SAVE FIFTH AVENUE Prestige of Great Shopping Area Now Menaced by Traffic Jam, He Declares". The New York Times. September 12, 1927. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- "FIRST AVENUE BODY URGES QUEENS TUNNEL; It Sees Thirty-eighth St. Connection as Aid to Trade in East River Section". The New York Times. September 21, 1927. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ "URGE CITY TO SPEED BRIDGE AND TUNNEL; Thirty-five Civic Bodies Join in Plea to Walker for Quick Action to Relieve Traffic. WANT TRI-BOROUGH SPAN Business Men Oppose Waiting for Engineers' Survey, Holding Situation Is Acute. CALL FOR A MIDTOWN TUBE Project for 38th St. Under East River Deemed Vital--Other Proposals Pressed. All Favor Bridge and Tunnel. Call Relief Plans Urgent". The New York Times. February 5, 1929. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ Duffus, R.l. (May 20, 1928). "A MIDTOWN TUNNEL FOR VEHICLES IS PROPOSED; Civic Bodies Support a Thirty-Eighty Street Project to Put Interborough Trucking Underground, Freeing Business Centre From Extra Traffic Conditions that Led to It. Queensboro Bridge Traffic. Carrying Extra Load. A $50,000,000 Job. An Urban Preserve. Tunnel Authority Suggested. Control by the City. Further Tunneling Indicated". The New York Times. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ↑ "FAVORS TOLLS FOR TRI-BORO BRIDGE; Feasibility of That Plan Explained by Queens Chamber of Commerce. URGES QUICK CONSTRUCTION Believes Land Value Increase Will More Than Offset Cost of Work. Toll-Operated Bridge. Terminal Locations". The New York Times. December 2, 1928. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ "URGES AN EARLY START ON EAST RIVER TUNNEL; Committee Asserts Vehicular Tube Would Relieve Chief Arteries of Midtown Manhattan". The New York Times. March 17, 1929. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ "MERCHANTS FAVOR EAST RIVER TUBE; Fifth Avenue Association Endorses Manhattan-Brooklyn-Queens Tunnel. FINANCIAL PLAN OUTLINED Would Create Special Body for Construction Under City Supervision". The New York Times. December 9, 1928. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ "ASKS ARTERY TO LINK MIDTOWN TO QUEENS; State Chamber of Commerce in Resolution Urges Bridge or Tunnel Near 38th Street. TRAFFIC RELIEF IS SOUGHT, Would Aid Industrial Area on Long Island, Says Speaker, and Spread Population. KELLOGG TREATY ENDORSED Organization Also Unanimously Approves Coolidge's Stand on 15 New Cruisers. Sees Cut in Traffic Delays. Praise Port Authority". The New York Times. January 4, 1929. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ "Traffic Relief to be Study of Harvey Group" (PDF). Brooklyn Daily Star. January 25, 1929. p. 2. Retrieved April 16, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "HARVEY GIVES OUT HIS HIGHWAY SURVEY". The New York Times. April 27, 1929. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ "URGES 5 NEW LINKS ACROSS EAST RIVER". The New York Times. May 25, 1929. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ "TRIBOROUGH TUBE PLANNED ACROSS CITY AT 38TH ST. AND UNDER EAST RIVER". The New York Times. June 7, 1929. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ "TOLLS AUTHORIZED FOR 38TH ST. TUBE". The New York Times. June 11, 1929. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ "NEW MIDTOWN TUNNEL WORK SEEN THIS YEAR FOLLOWING TOLL O.K." (PDF). Long Island Daily Press. June 14, 1929. p. 1. Retrieved April 16, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "TUNNEL PROJECTS BY CITY FACE DELAY". The New York Times. June 28, 1929. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ "SEEK QUICK ACTION ON 38TH ST. TUBE". The New York Times. July 21, 1929. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ "CITY VOTES $5,000,000 ASSURING MIDTOWN AND NARROWS TUBES". The New York Times. July 26, 1929. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ↑ "BOARD OF TRANSPORTATION TO RUSH PLANS FOR BUILDING MIDTOWN VEHICLE TUNNEL". Long Island Daily Press. July 26, 1929. pp. 1, 5 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "STUDY WAY TO LINK TWO NEW TUNNELS". The New York Times. January 14, 1930. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ "Tunnel Plans Are Modified" (PDF). The New York Sun. January 25, 1930. p. 8. Retrieved April 16, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "FINISHING TUNNEL PLANS.; Engineers Mapping Final Details of 38th Street Project". The New York Times. June 8, 1930. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ "TWO-STREET ROUTE FOR MIDTOWN TUBE". The New York Times. September 19, 1930. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ "ADVOCATES REVISING 38TH ST. TUNNEL PLAN; Midtown Group Says Forcing Autos to Street for Part of Trip Would Discourage Use. FEARS REVENUE WILL BE HIT Urges on Delaney a 100 Per Cent Underground Artery for Crossing City. COST WOULD BE GREATER But Association Asserts There Would Be Congestion at Entrances and Exits as Now Designed". The New York Times. November 10, 1930. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ "ASK ELEVATED ROAD TO 38TH ST. TUNNEL". The New York Times. November 11, 1930. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ "U.S. Approves 38th St. Tube In East River" (PDF). Brooklyn Daily Eagle. December 30, 1930. p. 2. Retrieved April 16, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- 1 2 "EAST RIVER TUNNEL APPROVED BY ARMY". The New York Times. December 31, 1930. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ "$93,600,000 PROJECT FOR MIDTOWN TUNNEL UP FOR CITY ACTION". The New York Times. June 13, 1931. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ "CITY ACTS TO PRESS 38TH STREET TUNNEL; Board Votes $200,000 to Keep Present Force at Work on Contracts and Plans. START BY MARCH HOPED FOR Sullivan Sees 5 Years Needed to Build East River Tubes and 4 for Those Under Island. SPEED URGED BY PEDRICK He Holds $93,000,000 Project Must Keep Pace With the Tunnel Planned Under the Hudson. Resolutions Are Approved. Pedrick Wants Action". The New York Times. October 7, 1931. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ Associated Press (July 27, 1933). "N.Y.BODY ASKS FEDERAL AID ON WORK PROJECTS" (PDF). Rochester Times-Union. p. 14. Retrieved April 16, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "FEDERAL AID SOUGHT FOR PROJECTS HERE; $1,400,000 Urged for State Park Roads -- Loan Planned for Triborough Bridge. EAST RIVER TUBE INCLUDED Civic Bodies Open Drive to Borrow From New Relief Fund to Speed Traffic Routes". The New York Times. July 19, 1932. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ "Board Is Assailed For Ignoring Boro In Tunnel Plans" (PDF). North Shore Daily Journal. December 28, 1933. p. 1. Retrieved April 16, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "Midtown Tunnel Authority Bill Is Signed by Lehman" (PDF). Brooklyn Daily Eagle. November 26, 1935. pp. 10A. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "3 NAMED TO BUILD EAST RIVER TUNNEL; Mayor Appoints A.T. Johnston, W.H. Friedman and Alfred B. Jones, Chairman". The New York Times. June 23, 1935. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ "TUNNEL HELD NEED FOR WORLD'S FAIR; La Guardia Urges Completion of the 38th St. Vehicular Tube by 1939". The New York Times. October 18, 1935. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ "$58,365,000 ASKED FOR QUEENS TUNNEL; PWA Loan Is Sought for Most of Money Needed to Build Vehicular Passage". The New York Times. September 16, 1935. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- 1 2 "EAST RIVER TUNNEL GETS OFFER BY RFC; Jesse Jones Says Corporation Will Lend $47,130,000 if PWA Grants $11,250,000". The New York Times. November 8, 1935. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "Cash Available For Building Of Midtown Link" (PDF). North Shore Daily Journal. November 26, 1935. p. 1. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "Brooklyn Spur To Tunnel Out, Says Friedman" (PDF). Brooklyn Daily Eagle. September 15, 1936. p. 8. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "Club Seeks Brooklyn Spur To Queens–Midtown Tunnel" (PDF). Brooklyn Daily Eagle. October 26, 1938. p. 1. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "AUTHORITY IS SET UP TO BUILD 2 TUNNELS; Legislature Quickly Passes Bill to Meet PWA Demands for 38th St.-Queens Project. BROOKLYN TUBE INCLUDED Battery-Hamilton Av. Plan Is Backed by Taylor – Speedy Approval by Lehman Likely". The New York Times. January 8, 1936. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "TUNNEL TO QUEENS TO START IN MONTH". The New York Times. January 5, 1936. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "City to Speed Work On East River Tunnel" (PDF). Brooklyn Daily Eagle. January 12, 1936. pp. 10A. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "TUNNEL AUTHORITY ACCEPTS PWA FUND; Federal Loan and Grant of $58,365,000 to Be Used for East River Vehicular Tube". The New York Times. March 8, 1936. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Mayor to Open Air Valves for Work in Tunnel" (PDF). Brooklyn Daily Eagle. April 10, 1938. pp. A7. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- 1 2 "CONTRACT IS LET FOR QUEENS TUBE; Walsh Company Will Build the $58,000,000 Vehicular Tunnel--Largest PWA Project". The New York Times. June 1, 1937. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- 1 2 "BRIDGE, NOT TUNNEL, TO QUEENS IS URGED". The New York Times. April 13, 1936. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "INGERSOLL FAVORS EAST RIVER BRIDGE". The New York Times. April 19, 1936. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "DESMOND PROPOSES EAST RIVER BRIDGE". The New York Times. April 20, 1936. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Caro, Robert A. (1974). The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. A Borzoi book. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-48076-3.

- ↑ "PWA ORDERS TUNNEL WORK TO GO AHEAD" (PDF). North Shore Daily Journal. April 15, 1936. p. 1. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "OPENS FIGHT FOR TUNNEL; Queens Chamber Rallies Forces to Combat Drive for Bridge". The New York Times. April 16, 1936. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "PWA ORDERS TUNNEL WORK TO GO AHEAD" (PDF). Long Island Daily Press. April 15, 1936. p. 1. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ Warn, W.a. (May 15, 1936). "LEGISLATURE ENDS; A SPECIAL SESSION IS NOW PREDICTED". The New York Times. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "PLANS APPROVED FOR QUEENS TUBE". The New York Times. August 7, 1936. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "Take First Step in Construction of Motor Tube" (PDF). North Shore Daily Journal. August 31, 1936. p. 1. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "PRESIDENT STARTS EAST RIVER TUNNEL". The New York Times. October 3, 1936. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "MIDTOWN TUBE IS DEDICATED BY PRESIDENT" (PDF). Long Island Daily Press. October 3, 1936. p. 1. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- 1 2 "Whole Job Sandwiched Between Visits By F. D. R." (PDF). Long Island City Star Journal. December 21, 1940. p. 2. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "TEST BORING ORDERED FOR EAST RIVER TUBE; Engineers Will Probe Bottom of Stream Through Which Tunnel Must Pass". The New York Times. October 17, 1936. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "DIAMOND 'SET BIT USED IN NEW TUBE". The New York Times. May 23, 1937. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "New Auto Tunnel Is Engineering 'Headache'" (PDF). Long Island Daily Press. November 22, 1936. p. 16. Retrieved April 16, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "QUEENS TUBE TESTS REVEAL HARD TASK; Borings, However, Indicate No Unusual Difficulties for East River Tunnel. ROCK OBSTACLES MANY Engineers Find One Deep Spot Where Clay Must Be Used to Protect Completed Job". The New York Times. November 27, 1936. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "EAST RIVER TUNNEL IS SPEEDED BY CITY". The New York Times. December 25, 1936. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "GROUND IS BROKEN FOR TUNNEL WORK". The New York Times. December 1, 1936. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "GETS LAND FOR TUNNEL". The New York Times. April 13, 1937. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "PWA GIVES $500,000 TO TUNNEL BOARD". The New York Times. January 10, 1937. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "' BLANKET' IN RIVER TO PROTECT TUNNEL; 40-Foot Thickness of Clay to Prevent Compressed Air From Bursting Through". The New York Times. April 13, 1937. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "SANDHOGS ADVANCE EAST RIVER TUNNEL". The New York Times. October 2, 1938. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "NEW DELAY FACES TUNNEL TO QUEENS; Col. Copp Tells of Four Months' Negotiations on Clay Blanket--Completion in 1940 Seen". The New York Times. April 1, 1937. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "Queens Tunnel Contract Let To Walsh Firm" (PDF). Brooklyn Daily Eagle. July 1, 1937. p. 5. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "Getting Down to Big Business on the New $58,000,000 Queens–Midtown Tunnel" (PDF). Brooklyn Daily Eagle. April 18, 1937. pp. A7. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "MODERN DEVICES TO GUARD SANDHOG; Elaborate Precautions Made to Ward Off 'Bends' From Workers in New Tube". The New York Times. April 18, 1937. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "Highway Link To New Tunnel" (PDF). North Shore Daily Journal. December 30, 1937. p. 1. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "FUNDS AUTHORIZED FOR AIRPORT LINK". The New York Times. October 18, 1940. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Chamber Hits Authorities for Lack of Tunnel" (PDF). Brooklyn Daily Eagle. March 29, 1937. p. 18. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "New St. Gabriel Site Acquired by Catholics". The New York Times. April 16, 1953. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ "LABOR COSTS SEEN AS BAR TO TUNNEL". The New York Times. January 23, 1938. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "Most Contracts Let For Midtown Tube" (PDF). Brooklyn Daily Eagle. August 25, 1938. p. 12. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- 1 2 "MAYOR VISITS TUBE IN SANDHOG'S TOGS". The New York Times. April 12, 1938. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "Under River Tube Boring Starts Feb. 1" (PDF). Brooklyn Daily Eagle. January 6, 1938. p. 5. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "Harvey and Isaacs Clash Over Midtown Tunnel" (PDF). Brooklyn Daily Eagle. December 9, 1938. p. 19. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ Associated Press (March 17, 1939). "NEW OXYGEN EQUIPMENT; Will be used by tunnel workers to prevent "the bends"" (PDF). Buffalo Courier Express. p. 3. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "Queens–Midtown Tunnel Is One-Quarter Finished". The New York Times. September 19, 1938. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "Midtown Tunnel Behind Schedule" (PDF). Brooklyn Daily Eagle. March 10, 1939. p. 10. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "MOSES TAKES FLING AT QUEENS TUNNEL; Predicts Financial Straits for It Soon, in New Attack on Battery Tube Plan REPLIES TO BRIDGE CRITICS No Danger to Realty Values, He Says--Friedman Scoffs at Arguments on Costs". The New York Times. February 8, 1939. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ↑ "Grade-Crossing Bill Ready for Senate Passage" (PDF). New York Post. February 14, 1939. p. 2. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "TUBES 60% COMPLETED; Progress on Queens Tunnel Is Reported by Singstad". The New York Times. May 7, 1939. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "STRIKE ON TUNNEL AND AQUEDUCT ENDS; Arbitration Agreement to Send Men Back to Jobs Today". The New York Times. July 19, 1939. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "TUNNEL TO QUEENS HAS 850 FEET TO GO; Sandhogs Expected to 'Hole Through' From Both Sides Some Time in November". The New York Times. July 31, 1939. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Tunnel to Queens 70 Percent Bored" (PDF). Brooklyn Daily Eagle. July 31, 1939. p. 2. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "New Record Set On Midtown Tube" (PDF). Brooklyn Daily Eagle. September 10, 1939. pp. A3. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "NEW QUEENS TUBES 'HOLE THROUGH' SOON; Midtown Tunnel Likely to Be Joined About Oct. 31". The New York Times. September 28, 1939. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Queens Midtown Tunnel Advances Another Step" (PDF). Brooklyn Daily Eagle. November 6, 1939. p. 3. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "Tunnel 'Holed Through' In Almost Perfect Line". The New York Times. November 12, 1939. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ "1,622 Iron Rings Installed In New Midtown Tunnel". The New York Times. January 8, 1940. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ "RAZE QUEENS BUILDINGS; Contractors Preparing Site for New Tunnel Approach". The New York Times. January 16, 1940. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ "NEW TUNNEL 90% FINISHED; Only 3 More Contracts to Be Let for Queens Midtown Tube". The New York Times. May 16, 1940. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Queens–Midtown Tunnel Will Be Ready on Time" (PDF). Long Island Daily Press. October 5, 1940. p. 2. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "PRESIDENT THE 'FIRST' TO USE MIDTOWN TUBE; Precedence at Opening Denied Hundreds of Motorists". The New York Times. November 9, 1940. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ Markland, John (November 10, 1940). "QUEENS MIDTOWN TUBE TO OPEN; Vehicular Tunnel, Ready for Public on Friday, Links Manhattan To Long Island and Will Relieve Traffic on City's Bridges". The New York Times. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Queens–Midtown Tunnel, The All-Weather Route, Opens Friday, Nov 15th" (PDF). Brooklyn Daily Eagle. November 7, 1940. p. 7. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "Midtown Tunnel Will Enhance New Home Building in Queens". The New York Times. November 17, 1940. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ "$58,000,000 Tunnel to Queens Opened". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. November 15, 1940. pp. 1, 4 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ Harrington, John W. (December 8, 1940). "NOVEL LIGHTING FOR NEW TUNNEL AJUSTABLE TO EASE EYE STRAIN". The New York Times. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ "150 TUNNEL GUARDS WILL BE GRADUATED; Ceremony Today to Be Followed by Fire-Fighting Show". The New York Times. November 12, 1940. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ "12 WOMEN TAKE OVER TUNNEL TOLL BOOTH; Five Replace Husbands, Now in Our Armed Services". The New York Times. April 15, 1943. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Midtown Tunnel May Be Opened To Traffic In Fifteen Months" (PDF). Long Island Star-Journal. August 14, 1939. p. 3. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "QUEENS TUNNEL TRAFFIC LAGS" (PDF). New York Sun. May 9, 1941. p. 21. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "Millionth Car Uses Queens Tube But the Big Mystery Is When". The New York Times. February 15, 1941. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ "MOTORING HERE CUT 29% BY RATIONING; Decline Reported for July by 2 Tunnels and 4 Bridges of Port Authority HUDSON CROSSINGS DROP Staten Island Links Also Show Decrease From Last Year -- Triborough Data Withheld". The New York Times. August 4, 1942. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Tunnel Open 24 Hours" (PDF). Port Jefferson Messenger. July 7, 1944. p. 3. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "$5,787,068 DEFICIT FOR MIDTOWN TUBE". The New York Times. January 25, 1946. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ "72% TRAFFIC RISE IN MIDTOWN TUNNEL; Triborough Authority Reports Bridge Gains--Seeks Battery Parking Garage Funds Parking Garage Funds Sought Bridge Traffic Increases". The New York Times. July 31, 1946. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ "FIRST PROFIT SHOWN BY QUEENS TUNNEL". The New York Times. January 31, 1949. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Queens Tunnel Shows Profit" (PDF). Long Island City Star Journal. January 31, 1949. p. 1. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ Ingraham, Joseph C. (August 14, 1950). "AVIATION TERMINAL TO COST $4,000,000 SET FOR FIRST AVE.; Triborough Authority Reaches Accord With Major Airlines --City Approval Needed PARKING GARAGE INCLUDED New Facility Between 37th and 38th Streets Slated to Be Ready Late in 1951". The New York Times. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ International News Service (August 14, 1950). "Airlines Plan for Bus Terminal to End Congestion" (PDF). The Journal News. Nyack, NY. p. 1. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "NEW AIRLINES CENTER SET FOR DEDICATION". The New York Times. November 28, 1953. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ Berger, Joseph (February 14, 1985). "AIRLINES TERMINAL ON EAST SIDE SOLD FOR $90.6 MILLION". The New York Times. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ Bagli, Charles V. (August 21, 2005). "Developers Find Newest Frontier on the East Side". The New York Times. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ↑ Bennett, Charles G. (June 20, 1950). "TRIBOROUGH DROPS MIDTOWN CROSSING; Authority, Once Ready to Build Highway Rather Than Tunnel, Now Says It Will Do Neither TRIBOROUGH DROPS MIDTOWN CROSSING The Authority's Viewpoint". The New York Times. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Moses Seeks 3rd Tube For Midtown Tunnel" (PDF). Long Island City Star Journal. May 19, 1959. p. 1. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- 1 2 Ingraham, Joseph C. (January 1, 1965). "Third Tube for Midtown Tunnel Advanced by Plan for New Study". The New York Times. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ↑ "Third-Tube Survey For Queens-Midtown" (PDF). Greenpoint Weekly Star. April 20, 1962. p. 2. Retrieved April 21, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ For the study itself, see:

- Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority (1965). Queens Midtown Tunnel: Third Tube. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ↑ "Expressway Plans". Regional Plan News. Regional Plan Association (73–74): 1–18. May 1964. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ↑ Kessler, Felix (June 18, 1963). "Dream Road Links Nothing" (PDF). Brooklyn World-Telegram. Fultonhistory.com. p. B1. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ↑ "Barnes Report Cites Need For Cross-Bklyn X-Way" (PDF). Brooklyn Home-Reporter. September 24, 1965. p. 8. Retrieved April 21, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ Ingraham, Joseph C. (December 29, 1965). "3d Midtown Tube to Start Soon, Moses Says, Shelving Road Plan; Midtown Tube to Start Soon, Moses' Says, Shelving Road Plan". The New York Times. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ↑ "Queens Chamber Endorses Third Midtown Tube" (PDF). Ridgewood Times. January 6, 1966. p. 5. Retrieved April 21, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ Knowles, Clayton (March 22, 1966). "Moses, Defying City, Asks Bids on New Tube Borings; AUTHORITY ASKS TUBE BORING BIDS". The New York Times. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ↑ "Moses On 3rd Tube: 'Dig We Will'" (PDF). Long Island Star-Journal. March 22, 1966. p. 1. Retrieved April 16, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "Traffic Over BayDrops During 1967" (PDF). Rockaway Wave. February 29, 1968. p. 2. Retrieved April 21, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ Carmody, Deirdre (October 27, 1971). "Special Rush‐Hour Bus Lane Makes Expressway a Breeze". The New York Times. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ↑ "Elephant Promenade through Queens Midtown Tunnel" (Press release). MTA Bridges & Tunnels. March 14, 2008. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ↑ "Circus predawn march" (PDF). N.Y. Amsterdam News. March 28, 1981. p. 68. Retrieved April 21, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ Allen, Mike (February 19, 1995). "These Days, the Circus Animals Sneak Into Town". The New York Times. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ↑ Barry, Dan (March 22, 2006). "The Manhattan of Beasts". The New York Times. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ↑ "Ringling Bros. And Barnum & Bailey To End Elephant Acts This May". CBS New York. January 11, 2016. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ "Ringling Bros. Elephants Are Taking Early Retirement to Florida". The New York Times. January 12, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ↑ Pierre-Pierre, Garry (July 31, 1997). "Giuliani Seeks Delay in Midtown Tunnel Repairs". The New York Times. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ↑ Adcock, Sylvia (January 3, 1998). "A Long Overhaul". Newsday.

- ↑ Nelson, Brett (October 29, 2001). "Sticky Situation". Forbes. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ↑ Levy, Clifford J. (April 3, 1998). "Judge Rules for M.T.A. on Tunnel Contract Linked to Pataki Donor". The New York Times. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ↑ "Press Release – Bridges & Tunnels – Queens Midtown Tunnel Air System Overhaul". MTA. May 14, 2008. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ↑ Kennedy, Randy (September 26, 2001). "Ban on Lone Drivers at Some New York Gates". The New York Times. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ↑ Kennedy, Randy (April 19, 2002). "Lone Drivers? Some Can Come Into Manhattan". The New York Times. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ↑ "Cuomo had the MTA waste $30M on tunnel vanity project". New York Post. 2018-07-23. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- ↑ "Queens Bus Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. December 2017. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ↑ "2017 Toll Information". MTA Bridges & Tunnels. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- 1 2 Siff, Andrew (October 5, 2016). "Automatic Tolls to Replace Gates at 9 NYC Spans: Cuomo". NBC New York. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- 1 2 WABC (December 21, 2016). "MTA rolls out cashless toll schedule for bridges, tunnels". ABC7 New York. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

External links

Route map:

![]()

- Queens Midtown Tunnel Turns 70. (November 15, 2010). MTA's Facebook page.

- Queens Midtown Tunnel Marks 70th Birthday. (November 15, 2010). NY1 local news channel.