Meditation

Meditation is a practice where an individual uses a technique, such as focusing their mind on a particular object, thought or activity, to achieve a mentally clear and emotionally calm state.[1]

Meditation has been practiced since antiquity in numerous religious traditions and beliefs. Since the 19th century, it has spread from its origins to other cultures where it is commonly practiced in private and business life.

Meditation may be used with the aim of reducing stress, anxiety, depression, and pain, and increasing peace, perception,[2] self-concept, and well-being.[3][4][5][6] Meditation is under research to define its possible health (psychological, neurological, and cardiovascular) and other effects.

Etymology

The English meditation is derived from the Latin meditatio, from a verb meditari, meaning "to think, contemplate, devise, ponder".[7]

In the Old Testament, hāgâ (Hebrew: הגה) means to sigh or murmur, and also, to meditate.[8] When the Hebrew Bible was translated into Greek, hāgâ became the Greek melete. The Latin Bible then translated hāgâ/melete into meditatio.[9] The use of the term meditatio as part of a formal, stepwise process of meditation goes back to the 12th-century monk Guigo II.[10]

In addition within specific contexts more precise meanings are not uncommonly given the word "meditation".[11] For example, "meditation" is sometimes the translation of meditatio in Latin. Meditatio is the second of four steps of Lectio Divina, an ancient form of Christian prayer. "Meditation" also refers to the seventh of the eight limbs of Yoga in Patanjali's Yoga Sutras, a step called dhyāna in Sanskrit. Meditation refers to a mental or spiritual state that may be attained by such practices,[12] and also refers to the practice of that state.

Apart from its historical usage, the term meditation was introduced as a translation for Eastern spiritual practices, referred to as dhyāna in Hinduism and Buddhism and which comes from the Sanskrit root dhyai, meaning to contemplate or meditate.[12][13] The term "meditation" in English may also refer to practices from Islamic Sufism,[14] or other traditions such as Jewish Kabbalah and Christian Hesychasm.[15] An edited book about "meditation" published in 2003, for example, included chapter contributions by authors describing Hindu, Buddhist, Taoist, Jewish, Christian, and Islamic traditions.[16][17] Scholars have noted that "the term 'meditation' as it has entered contemporary usage" is parallel to the term "contemplation" in Christianity,[18] but in many cases, practices similar to modern forms of meditation were simply called "prayer". Christian, Judaic, and Islamic forms of meditation are typically devotional, scriptural or thematic, while Asian forms of meditation are often more purely technical.[19]

Definitions

In popular usage, the word "meditation" and the phrase "meditative practice" are often used imprecisely to designate broadly similar practices, or sets of practices, that are found across many cultures and traditions.[15][20] Definitions in the Oxford and Cambridge living dictionaries are "to focus one's mind for a period of time"[21] and "the act of giving your attention to only one thing."[22] What is considered meditation can include almost any practice that trains the attention or teaches calm or compassion.[23]

A 2009 study of views common to seven experts trained in diverse but empirically highly studied (clinical or Eastern-derived) forms of meditation[24] identified "three main criteria... as essential to any meditation practice: the use of a defined technique, logic relaxation, and a self-induced state/mode. Other criteria deemed important [but not essential] involve a state of psychophysical relaxation, the use of a self-focus skill or anchor, the presence of a state of suspension of logical thought processes, a religious/spiritual/philosophical context, or a state of mental silence."[25]:135 However, the study cautioned, "It is plausible that meditation is best thought of as a natural category of techniques best captured by 'family resemblances'... or by the related 'prototype' model of concepts."[25]:135[26]

The table shows several other definitions of meditation that have been used by influential modern reviews of research on meditation across multiple traditions.

| Definitions or Characterizations of Meditation: Examples from Prominent Reviews* | |

| Definition / Characterization | Review |

| • "[M]editation refers to a family of self-regulation practices that focus on training attention and awareness in order to bring mental processes under greater voluntary control and thereby foster general mental well-being and development and/or specific capacities such as calm, clarity, and concentration"[27]:228–9 | Walsh & Shapiro (2006) |

| • "[M]editation is used to describe practices that self-regulate the body and mind, thereby affecting mental events by engaging a specific attentional set.... regulation of attention is the central commonality across the many divergent methods"[28]:180 | Cahn & Polich (2006) |

| • "We define meditation... as a stylized mental technique... repetitively practiced for the purpose of attaining a subjective experience that is frequently described as very restful, silent, and of heightened alertness, often characterized as blissful"[29]:415 | Jevning et al. (1992) |

| • "the need for the meditator to retrain his attention, whether through concentration or mindfulness, is the single invariant ingredient in... every meditation system"[15]:107 | Goleman (1988) |

| *Influential reviews encompassing multiple methods of meditation

(The first 3 are cited >80 times in PsycINFO.[30] Goleman's book has 33 editions listed in WorldCat: 17 editions as The meditative mind: The varieties of meditative experience and 16 editions as The varieties of meditative experience. Citation and edition counts are as of August 2018 and September 2018 respectively.) | |

In modern psychological research, meditation has been defined and characterized in a variety of ways; many of these emphasize the role of attention.[15][27][28][29] Scientific reviews have proposed that researchers attempt to more clearly define the type of meditation being practiced in order that the results of their studies be made clearer.[31]:499 One review of the field provides a detailed set of questions as a starting point in reaching this goal.[23]

Separation of technique from tradition

Some of the difficulty in precisely defining meditation has been the need to recognize the particularities of the many various traditions.[31] There may be differences between the theories of one tradition of meditation as to what it means to practice meditation.[32] The differences between the various traditions themselves, which have grown up a great distance apart from each other, may be even starker.[32] Taylor noted that to refer only to meditation from a particular faith (e.g., "Hindu" or "Buddhist")

...is not enough, since the cultural traditions from which a particular kind of meditation comes are quite different and even within a single tradition differ in complex ways. The specific name of a school of thought or a teacher or the title of a specific text is often quite important for identifying a particular type of meditation.[33]:2

Ornstein noted that "Most techniques of meditation do not exist as solitary practices but are only artificially separable from an entire system of practice and belief."[34]:143 This means that, for instance, while monks engage in meditation as a part of their everyday lives, they also engage the codified rules and live together in monasteries in specific cultural settings that go along with their meditative practices. These meditative practices sometimes have similarities (often noticed by Westerners), for instance concentration on the breath is practiced in Zen, Tibetan and Theravadan contexts, and these similarities or "typologies" are noted here.

Usage in this article

This article mainly focuses on meditation in the broad sense of a type of technique, found in various forms in many cultures, by which the practitioner attempts to get beyond the reflexive, "thinking" mind[35] (sometimes called "discursive thinking"[36] or "logic"[37]) This may be to achieve a deeper, more devout, or more relaxed state. The terms "meditative practice" and "meditation" are mostly used here in this broad sense. However, usage may vary somewhat by context – readers should be aware that in quotations, or in discussions of particular traditions, more specialized meanings of "meditation" may sometimes be used (with meanings made clear by context whenever possible).

Forms of meditation

Focused vs open monitoring meditation

In the West, meditation techniques have sometimes been thought of in two broad categories: focused (or concentrative) meditation and open monitoring (or mindfulness) meditation.[38]

One style, Focused Attention (FA) meditation, entails the voluntary focusing of attention on a chosen object, breathing, image, or words. The other style, Open Monitoring (OM) meditation, involves non-reactive monitoring of the content of experience from moment to moment.[38]

Direction of mental attention... A practitioner can focus intensively on one particular object (so-called concentrative meditation), on all mental events that enter the field of awareness (so-called mindfulness meditation), or both specific focal points and the field of awareness.[25]:130[39]

Focused attention methods

These include paying attention to the breath, to an idea or feeling (such as mettā (loving-kindness)), or to a mantra (such as in transcendental meditation), and single point meditation.[40][41]

Open monitoring methods

These include mindfulness, shikantaza and other awareness states.[42]

Practices using both methods

Some practices use both techniques,[43][44][45] including vipassana (which uses anapanasati as a preparation), samatha/calm-abiding,[46][47] and Headspace.[48]

No thought

In these methods, "the practitioner is fully alert, aware, and in control of their faculties but does not experience any unwanted thought activity."[49] This is in contrast to the common meditative approaches of being detached from, and non-judgmental of, thoughts, but not of aiming for thoughts to cease.[50] In the meditation practice of the Sahaja yoga spiritual movement, the focus is on thoughts ceasing.[51] Clear light yoga also aims at a state of no mental content, as does the no thought (wu nian) state taught by Huineng,[52] and the teaching of Yaoshan Weiyan.

Automatic self-transcending

One proposal is that transcendental meditation and possibly other techniques be grouped as an 'automatic self-transcending' set of techniques.[53]

Other typologies

Other typologies include dividing meditation into concentrative, generative, receptive and reflective practices.[54]

Meditation methods used by some well-known meditators

- Multiple methods; Pema Chödrön (shambhala - uses multiple methods), Susan Piver (shambhala), S.N.Goenka (vipassana - uses multiple methods), Joseph Goldstein (vipassana), Judson Brewer[55] (vipassana), Yuval Harari (vipassana), 14th Dalai Lama (various,[56] including analytic meditation[57]), Matthieu Ricard (loving-kindness, open awareness, analytic[58]), Sharon Salzberg (loving-kindness,[59] mindfulness,[60] vipassana), Daniel Goleman (dzogchen, other[61]), Thubten Chodron (stabilizing, analytical,[62] loving-kindness[63]), Martine and Stephen Batchelor (mindfulness breath, body, sounds, feeling tones (vedanas), Seon questioning, appreciative joy (mudita)).

- Open awareness; Jon Kabat-Zinn (mindfulness), Sam Harris (mindfulness).

- Chakra Meditation;[64] Michal Levin[65]

Meditation practice

Common practice timings

The transcendental meditation technique recommends practice of 20 minutes twice per day.[66] Some techniques suggest less time,[43] especially when starting meditation,[67] and Richie Davidson has quoted research saying benefits can be achieved with a practice of only 8 minutes per day.[68] Some meditators practice for much longer,[69][70] particularly when on a course or retreat.[71] Some meditators find practice best in the hours before dawn.[72]

Physical postures and techniques

Whilst positions such as the full-lotus, half-lotus, Burmese, Seiza, and kneeling positions are popular in Buddhism, Jainism and Hinduism, other postures such as sitting, supine (lying), and standing are also used. Meditation is also sometimes done while walking, known as kinhin, or while doing a simple task mindfully, known as samu.[73]

Use of prayer beads

Some ancient religions of the world have a tradition of using prayer beads as tools in devotional meditation.[74][75][76] Most prayer beads and Christian rosaries consist of pearls or beads linked together by a thread.[74][75] The Roman Catholic rosary is a string of beads containing five sets with ten small beads. The Hindu japa mala has 108 beads (the figure 108 in itself having spiritual significance, as well as those used in Jainism and Buddhist prayer beads.[77] Each bead is counted once as a person recites a mantra until the person has gone all the way around the mala.[77] The Muslim misbaha has 99 beads.

Possible benefits of supporting meditation practice with a narrative

Richie Davidson has expressed the view that having a narrative can help maintenance of daily practice.[68] For instance he himself prostrates to the teachings, and meditates "not primarily for my benefit, but for the benefit of others."[68]

Religious and spiritual meditation

Indian religions

Jainism

In Jainism, meditation has been a core spiritual practice, one that Jains believe people have undertaken since the teaching of the Tirthankara, Rishabha.[78] All the twenty-four Tirthankaras practiced deep meditation and attained enlightenment.[79] They are all shown in meditative postures in the images or idols. Mahavira practiced deep meditation for twelve years and attained enlightenment.[80] The Acaranga Sutra dating to 500 BCE, addresses the meditation system of Jainism in detail.[81] Acharya Bhadrabahu of the 4th century BCE practiced deep Mahaprana meditation for twelve years.[82] Kundakunda of 1st century BCE, opened new dimensions of meditation in Jain tradition through his books Samayasāra, Pravachansar and others.[83] The 8th century Jain philosopher Haribhadra also contributed to the development of Jain yoga through his Yogadṛṣṭisamuccaya, which compares and analyzes various systems of yoga, including Hindu, Buddhist and Jain systems.

Jain meditation and spiritual practices system were referred to as salvation-path. It has three important parts called the Ratnatraya "Three Jewels": right perception and faith, right knowledge and right conduct.[84] Meditation in Jainism aims at realizing the self, attaining salvation, take the soul to complete freedom.[85] It aims to reach and to remain in the pure state of soul which is believed to be pure consciousness, beyond any attachment or aversion. The practitioner strives to be just a knower-seer (Gyata-Drashta). Jain meditation can be broadly categorized to Dharmya Dhyana and Shukla Dhyana.

There exists a number of meditation techniques such as pindāstha-dhyāna, padāstha-dhyāna, rūpāstha-dhyāna, rūpātita-dhyāna, savīrya-dhyāna, etc. In padāstha dhyāna one focuses on Mantra.[86] A Mantra could be either a combination of core letters or words on deity or themes. There is a rich tradition of Mantra in Jainism. All Jain followers irrespective of their sect, whether Digambara or Svetambara, practice mantra. Mantra chanting is an important part of daily lives of Jain monks and followers. Mantra chanting can be done either loudly or silently in mind. Yogasana and Pranayama has been an important practice undertaken since ages. Pranayama – breathing exercises – are performed to strengthen the five Pranas or vital energy.[87] Yogasana and Pranayama balances the functioning of neuro-endocrine system of body and helps in achieving good physical, mental and emotional health.[88]

Contemplation is a very old and important meditation technique. The practitioner meditates deeply on subtle facts. In agnya vichāya, one contemplates on seven facts – life and non-life, the inflow, bondage, stoppage and removal of karmas, and the final accomplishment of liberation. In apaya vichāya, one contemplates on the incorrect insights one indulges, which eventually develops right insight. In vipaka vichāya, one reflects on the eight causes or basic types of karma. In sansathan vichāya, one thinks about the vastness of the universe and the loneliness of the soul.[86]

Acharya Mahapragya formulated Preksha meditation in the 1970s and presented a well-organised system of meditation. Asana and Pranayama, meditation, contemplation, mantra and therapy are its integral parts.[89] Numerous Preksha meditation centers came into existence around the world and numerous meditations camps are being organized to impart training in it.

Piyush Kumar Nahata,[90] an ex-Jain Monk created a meditation technique by the name of evo4soul.[91] He worked more than two decades to understand the process of evolution theory in the context of ancient Indian wisdom provided by Rishis, Tirthankaras and Buddhas. After a deep analysis of both systems he designed a genius system to evolve the soul. It’s a complete guide to align the body, mind and soul.

Buddhism

Buddhist meditation refers to the meditative practices associated with the religion and philosophy of Buddhism. Core meditation techniques have been preserved in ancient Buddhist texts and have proliferated and diversified through teacher-student transmissions. Buddhists pursue meditation as part of the path toward awakening and nirvana.[92] The closest words for meditation in the classical languages of Buddhism are bhāvanā,[93] jhāna/dhyāna,[94] and vipassana.

Buddhist meditation techniques have become increasingly popular in the wider world, with many non-Buddhists taking them up for a variety of reasons. There is considerable homogeneity across meditative practices – such as breath meditation and various recollections (anussati) – that are used across Buddhist schools, as well as significant diversity. In the Theravāda tradition alone, there are over fifty methods for developing mindfulness and forty for developing concentration, while in the Tibetan tradition there are thousands of visualization meditations.[95] Most classical and contemporary Buddhist meditation guides are school-specific.[96]

The Buddha is said to have identified two paramount mental qualities that arise from wholesome meditative practice:

- "serenity" or "tranquility" (Pali: samatha) which steadies, composes, unifies and concentrates the mind;

- "insight" (Pali: vipassana) which enables one to see, explore and discern "formations" (conditioned phenomena based on the five aggregates).[97]

According to Buddhist theory, through the meditative development of serenity, one is able to weaken the obscuring hindrances and bring the mind to a collected, pliant and still state (samadhi). This quality of mind then supports the development of insight and wisdom (Prajñā) which is the quality of mind that can "clearly see" (vi-passana) the nature of phenomena. According to the Buddhist tradition, all phenomena are to be seen as impermanent, suffering, not-self and empty. When this happens, one develops dispassion (viraga) for all phenomena, including all negative qualities and hindrances and lets them go. It is through the release of the hindrances and ending of craving through the meditative development of insight that one gains liberation.[98]

In the modern era, Buddhist meditation saw increasing popularity due to the influence of Buddhist modernism and the lay meditation based Vipassana movement. The spread of Buddhist meditation to the Western world paralleled the spread of Buddhism in the West. Buddhist meditation has also influenced Western Psychology, especially through the work of Jon Kabat-Zinn who founded the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) in 1979.[99] The modernized concept of mindfulness (based on the Buddhist term sati) and related meditative practices has in turn led to several mindfulness based therapies.

Hinduism

There are many schools and styles of meditation within Hinduism.[100]

Traditional

In pre-modern and traditional Hindu religions, Yoga and Dhyana are done to realize union of one's eternal self or soul, one's ātman. In some Hindu traditions, such as Advaita Vedanta this is equated with the omnipresent and non-dual Brahman. In others, such as the dualistic the Yoga school and Samkhya, the Self is referred to as Purusha, a pure consciousness which is separate from matter. Depending on the tradition, this liberative event is referred to as moksha, vimukti or kaivalya.

The earliest clear references to meditation in Hindu literature are in the middle Upanishads and the Mahabharata, the latter of which includes the Bhagavad Gita.[101][102] According to Gavin Flood, the earlier Brihadaranyaka Upanishad refers to meditation when it states that "having become calm and concentrated, one perceives the self (ātman) within oneself".[100]

One of the most influential texts of classical Hindu Yoga is Patañjali's Yoga sutras (c. 400 CE), a text associated with Yoga and Samkhya, which outlines eight limbs leading to kaivalya ("aloneness"). These are ethical discipline (yamas), rules (niyamas), physical postures (āsanas), breath control (prāṇāyama), withdrawal from the senses (pratyāhāra), one-pointedness of mind (dhāraṇā), meditation (dhyāna), and finally samādhi.

Later developments in Hind meditation include the compilation of Hatha Yoga (forceful yoga) compendiums like the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, the development of Bhakti yoga as a major form of meditation and Tantra. Another important Hindu yoga text is the Yoga Yajnavalkya, which makes use of Hatha Yoga and Vedanta Philosophy.

In the sixth chapter of Bhāvārthadipikā[103] commentary on the Bhagavad-Gita by Sri Jñāneśvar (Dnyaneshwar)[104] meditation in yoga is described as a state caused by the spontaneous awakening of the sacred energy Kundalini (not Prana or Chi), which creates a connection of the individual soul Ātman with universal Spirit - Paramātman.

Modern

Meditation is used in modern Hindu religious movements.

Sikhism

In Sikhism, simran (meditation) and good deeds are both necessary to achieve the devotee's Spiritual goals;[105] without good deeds meditation is futile. When Sikhs meditate, they aim to feel God's presence and immerge in the divine light.[106] It is only God's divine will or order that allows a devotee to desire to begin to meditate. Guru Nanak in the Japji Sahib daily Sikh scripture explains:

Visits to temples, penance, compassion and charity gain you but a sesame seed of credit. It is hearkening to His Name, accepting and adoring Him that obtains emancipation by bathing in the shrine of soul. All virtues are Yours, O Lord! I have none; Without good deeds one can't even meditate.[107]

Nām Japnā involves focusing one's attention on the names or great attributes of God.[108]

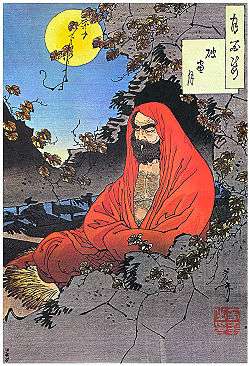

East Asian religions

Taoism

Taoist or Daoist meditation has a long history, and has developed various techniques including concentration, visualization, qi cultivation, contemplation, and mindfulness meditations. Traditional Daoist meditative practices were influenced by Chinese Buddhism beginning around the 5th century, and later had influence upon Traditional Chinese medicine and the Chinese martial arts.

Livia Kohn distinguishes three basic types of Daoist meditation: "concentrative", "insight", and "visualization".[109] Ding 定 (literally means "decide; settle; stabilize") refers to "deep concentration", "intent contemplation", or "perfect absorption". Guan 觀 (lit. "watch; observe; view") meditation seeks to merge and attain unity with the Dao. It was developed by Tang Dynasty (618–907) Daoist masters based upon the Tiantai Buddhist practice of Vipassanā "insight" or "wisdom" meditation. Cun 存 (lit. "exist; be present; survive") has a sense of "to cause to exist; to make present" in the meditation techniques popularized by the Daoist Shangqing and Lingbao Schools. A meditator visualizes or actualizes solar and lunar essences, lights, and deities within his/her body, which supposedly results in health and longevity, even xian 仙/仚/僊, "immortality".

The (late 4th century BCE) Guanzi essay Neiye "Inward training" is the oldest received writing on the subject of qi cultivation and breath-control meditation techniques.[110] For instance, "When you enlarge your mind and let go of it, when you relax your vital breath and expand it, when your body is calm and unmoving: And you can maintain the One and discard the myriad disturbances. ... This is called "revolving the vital breath": Your thoughts and deeds seem heavenly."[111]

The (c. 3rd century BCE) Daoist Zhuangzi records zuowang or "sitting forgetting" meditation. Confucius asked his disciple Yan Hui to explain what "sit and forget" means: "I slough off my limbs and trunk, dim my intelligence, depart from my form, leave knowledge behind, and become identical with the Transformational Thoroughfare."[112]

Daoist meditation practices are central to Chinese martial arts (and some Japanese martial arts), especially the qi-related neijia "internal martial arts". Some well-known examples are daoyin "guiding and pulling", qigong "life-energy exercises", neigong "internal exercises", neidan "internal alchemy", and taijiquan "great ultimate boxing", which is thought of as moving meditation. One common explanation contrasts "movement in stillness" referring to energetic visualization of qi circulation in qigong and zuochan "seated meditation",[45] versus "stillness in movement" referring to a state of meditative calm in taijiquan forms.

Iranian religions

Bahá'í Faith

In the teachings of the Bahá'í Faith, meditation along with prayer are both primary tools for spiritual development[113] and mainly refer to one's reflection on the words of God.[114] While prayer and meditation are linked, where meditation happens generally in a prayerful attitude, prayer is seen specifically as turning toward God,[115] and meditation is seen as a communion with one's self where one focuses on the divine.[114]

The Bahá'í teachings note that the purpose of meditation is to strengthen one's understanding of the words of God, and to make one's soul more susceptible to their potentially transformative power,[114] more receptive to the need for both prayer and meditation to bring about and maintain a spiritual communion with God.[116]

Bahá'u'lláh, the founder of the religion, never specified any particular form of meditation, and thus each person is free to choose their own form.[113] However, he specifically did state that Bahá'ís should read a passage of the Bahá'í writings twice a day, once in the morning, and once in the evening, and meditate on it. He also encouraged people to reflect on one's actions and worth at the end of each day.[114] During the Nineteen Day Fast, a period of the year during which Bahá'ís adhere to a sunrise-to-sunset fast, they meditate and pray to reinvigorate their spiritual forces.[117]

Abrahamic religions

Judaism

There is evidence that Judaism has had meditative practices that go back thousands of years.[118][119] For instance, in the Torah, the patriarch Isaac is described as going "לשוח" (lasuach) in the field—a term understood by all commentators as some type of meditative practice (Genesis 24:63).[120]

Similarly, there are indications throughout the Tanakh (the Hebrew Bible) that meditation was used by the prophets.[121] In the Old Testament, there are two Hebrew words for meditation: hāgâ (Hebrew: הגה), which means to sigh or murmur, but also to meditate, and sîḥâ (Hebrew: שיחה), which means to muse, or rehearse in one's mind.[122]

Some meditative traditions have been encouraged in the school of Judaism known as Kabbalah, and some Jews have described Kabbalah as an inherently meditative field of study.[123][124][125] Aryeh Kaplan has argued that, for the Kabbalist, the ultimate purpose of meditative practice is to understand and cleave to the Divine.[122] Classic methods include the mental visualisation of the supernal realms the soul navigates through to achieve certain ends. One of the best known types of meditation in early Jewish mysticism was the work of the Merkabah, from the root /R-K-B/ meaning "chariot" (of God).[122]

Meditation has been of interest to a wide variety of modern Jews. In modern Jewish practice, one of the best known meditative practices is called "hitbodedut" (התבודדות, alternatively transliterated as "hisbodedus"), and is explained in Kabbalistic, Hasidic, and Mussar writings, especially the Hasidic method of Rabbi Nachman of Breslav. The word derives from the Hebrew word "boded" (בודד), meaning the state of being alone.[126] Another Hasidic system is the Habad method of "hisbonenus", related to the Sephirah of "Binah", Hebrew for understanding.[127] This practice is the analytical reflective process of making oneself understand a mystical concept well, that follows and internalises its study in Hasidic writings.

The Musar Movement, founded by Rabbi Israel Salanter in the middle of the nineteenth-century, emphasized meditative practices of introspection and visualization that could help to improve moral character.[128]

Jewish Buddhists have adopted Buddhist styles of meditation.[129]

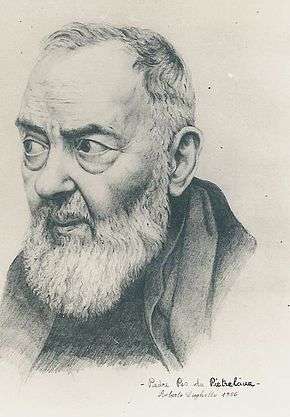

Christianity

Christian meditation is a term for a form of prayer in which a structured attempt is made to get in touch with and deliberately reflect upon the revelations of God.[131] The word meditation comes from the Latin word meditari, which means to concentrate. Christian meditation is the process of deliberately focusing on specific thoughts (e.g. a biblical scene involving Jesus and the Virgin Mary) and reflecting on their meaning in the context of the love of God.[132]

The Rosary is a devotion for the meditation of the mysteries of Jesus and Mary.[133][134]“The gentle repetition of its prayers makes it an excellent means to moving into deeper meditation. It gives us an opportunity to open ourselves to God’s word, to refine our interior gaze by turning our minds to the life of Christ. The first principle is that meditation is learned through practice. Many people who practice rosary meditation begin very simply and gradually develop a more sophisticated meditation. The meditator learns to hear an interior voice, the voice of God”.[135]

Christian meditation contrasts with Eastern forms of meditation as radically as the portrayal of God the Father in the Bible contrasts with depictions of Krishna or Brahman in Indian teachings.[136] Unlike Eastern meditations, most styles of Christian meditations do not rely on the repeated use of mantras, and yet are also intended to stimulate thought and deepen meaning. Christian meditation aims to heighten the personal relationship based on the love of God that marks Christian communion.[137][138]

In Aspects of Christian meditation, the Catholic Church warned of potential incompatibilities in mixing Christian and Eastern styles of meditation.[139] In 2003, in A Christian reflection on the New Age the Vatican announced that the "Church avoids any concept that is close to those of the New Age".[140][141][142]

Christian meditation is sometimes taken to mean the middle level in a broad three stage characterization of prayer: it then involves more reflection than first level vocal prayer, but is more structured than the multiple layers of contemplation in Christianity.[143]

In Frankfurt, Germany in 2007 the Centre for Christian Meditation and Spirituality in the Holy Cross Church, Frankfurt-Bornheim was founded by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Limburg. In and by the centre different kinds of church services are offered like for example with elements such as expressionist dance, moreover days of exercises of Christian mysticism, contemplative prayer, meditative singing, meditation courses, Zen-meditation courses, days of reflection, spiritual exercises and retreats[144]

Early studies on states of consciousness conducted by Roland Fischer [145] found evidence of mystical experience description in the writings of Saint Teresa of Avila. In her autobiography she describes that, at the peak of a praying experience "... the soul neither hears nor sees nor feels. While it lasts, none of the senses perceives or knows what is taking place".[146] This corresponds to the fourth stage described by Saint Teresa, "Devotion of Ecstasy", where the consciousness of being in the body disappears, as an effect of deep transcendent meditation in prayer.

Islam

Salah is a mandatory act of devotion performed by Muslims five times per day. The body goes through sets of different postures, as the mind attains a level of concentration called khushu'.

A second optional type of meditation, called dhikr, meaning remembering and mentioning God, is interpreted in different meditative techniques in Sufism or Islamic mysticism.[147][148] This became one of the essential elements of Sufism as it was systematized traditionally. It is juxtaposed with fikr (thinking) which leads to knowledge.[149] By the 12th century, the practice of Sufism included specific meditative techniques, and its followers practiced breathing controls and the repetition of holy words.[150]

Numerous Sufi traditions place emphasis upon a meditative procedure which comes from the cognitive aspect to one of the two principal approaches to be found in the Buddhist traditions: that of the concentration technique, involving high-intensity and sharply focused introspection. In the Oveyssi-Shahmaghsoudi Sufi order, for example, this is particularly evident, where muraqaba takes the form of tamarkoz, the latter being a Persian term that means "concentration".[151]

Tafakkur or tadabbur in Sufism literally means reflection upon the universe: this is considered to permit access to a form of cognitive and emotional development that can emanate only from the higher level, i.e. from God. The sensation of receiving divine inspiration awakens and liberates both heart and intellect, permitting such inner growth that the apparently mundane actually takes on the quality of the infinite. Muslim teachings embrace life as a test of one's submission to God.[152]

Pagan and occult religions

Religions and religious movements which use magic, such as Wicca, Thelema, Neopaganism, occultism etc., often require their adherents to meditate as a preliminary to the magical work. This is because magic is often thought to require a particular state of mind in order to make contact with spirits, or because one has to visualize one's goal or otherwise keep intent focused for a long period during the ritual in order to see the desired outcome. Meditation practice in these religions usually revolves around visualization, absorbing energy from the universe or higher self, directing one's internal energy, and inducing various trance states. Meditation and magic practice often overlap in these religions as meditation is often seen as merely a stepping stone to supernatural power, and the meditation sessions may be peppered with various chants and spells.

Modern spirituality

Mantra meditation, with the use of a japa mala and especially with focus on the Hare Krishna maha-mantra, is a central practice of the Gaudiya Vaishnava faith tradition and the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), also known as the Hare Krishna movement. Other popular New Religious Movements include the Ramakrishna Mission, Vedanta Society, Divine Light Mission, Chinmaya Mission, Osho, Sahaja Yoga, Transcendental Meditation, Oneness University, Brahma Kumaris and Vihangam Yoga.

New Age

New Age meditations are often influenced by Eastern philosophy, mysticism, yoga, Hinduism and Buddhism, yet may contain some degree of Western influence. In the West, meditation found its mainstream roots through the social revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, when many of the youth of the day rebelled against traditional religion as a reaction against what some perceived as the failure of Christianity to provide spiritual and ethical guidance.[153] New Age meditation as practised by the early hippies is regarded for its techniques of blanking out the mind and releasing oneself from conscious thinking. This is often aided by repetitive chanting of a mantra, or focusing on an object.[154] New Age meditation evolved into a range of purposes and practices, from serenity and balance to access to other realms of consciousness to the concentration of energy in group meditation to the supreme goal of samadhi, as in the ancient yogic practice of meditation.[155]

Mindfulness

Over the past 20 years, mindfulness and mindfulness-based programs have been used to assist people, whether they be clinically sick or healthy.[156] Jon Kabat-Zinn, who founded the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction program in 1979, has defined mindfulness as 'moment to moment non-judgmental awareness.'[157] Several methods are used during time set aside specifically for mindfulness meditation, such as body scan techniques or letting thought arise and pass, and also during our daily lives, such as being aware of the taste and texture of the food that we eat.[158] Some studies offer evidence that mindfulness practices are beneficial for the brain's self-regulation by increasing activity in the anterior cingulate cortex.[159] A shift from using the right prefrontal cortex is claimed to be associated with a trend away from depression and anxiety, and towards happiness, relaxation, and emotional balance.[160]

Secular applications

As stated by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, a US government entity within the National Institutes of Health that advocates various forms of Alternative Medicine, "Meditation may be practiced for many reasons, such as to increase calmness and physical relaxation, to improve psychological balance, to cope with illness, or to enhance overall health and well-being."[161][5]

Meditation techniques have also been used by Western theories of counseling and psychotherapy. Relaxation training works toward achieving mental and muscle relaxation to reduce daily stresses. Sahaja (mental silence) meditators scored above control group for emotional well-being and mental health measures on SF-36 ratings.[162][163]

Jacobson's Progressive Muscle Relaxation was developed by American physician Edmund Jacobson in the early 1920s. In this practice one tenses and then relaxes muscle groups in a sequential pattern whilst concentrating on how they feel. The method has been seen to help people with many conditions, especially extreme anxiety.[164] Jacobson is credited with developing the initial progressive relaxation procedure. These techniques are used in conjunction with other behavioral techniques. Originally used with systematic desensitization, relaxation techniques are now used with other clinical problems. Meditation, hypnosis and biofeedback-induced relaxation are a few of the techniques used with relaxation training.

One of the eight essential phases of EMDR (developed by Francine Shapiro), bringing adequate closure to the end of each session, also entails the use of relaxation techniques, including meditation. Multimodal therapy, a technically eclectic approach to behavioral therapy, also employs the use of meditation as a technique used in individual therapy.[165]

From the point of view of psychology and physiology, meditation can induce an altered state of consciousness.[166] Such altered states of consciousness may correspond to altered neuro-physiologic states.[167]

Today, there are many different types of meditation practiced in western culture. Mindful breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, and loving kindness meditations for instance have been found to provide cognitive benefits such as relaxation and decentering. With training in meditation, depressive rumination can be decreased and overall peace of mind can flourish. Different techniques have shown to work better for different people.[168]

Sound-based meditation

Herbert Benson of Harvard Medical School conducted a series of clinical tests on meditators from various disciplines, including the Transcendental Meditation technique and Tibetan Buddhism. In 1975, Benson published a book titled The Relaxation Response where he outlined his own version of meditation for relaxation.[169] Also in the 1970s, the American psychologist Patricia Carrington developed a similar technique called Clinically Standardized Meditation (CSM).[170] In Norway, another sound-based method called Acem Meditation developed a psychology of meditation and has been the subject of several scientific studies.[171]

Biofeedback has been used by many researchers since the 1950s in an effort to enter deeper states of mind.[172]

History

The history of meditation is intimately bound up with the religious context within which it was practiced.[173] Some authors have even suggested the hypothesis that the emergence of the capacity for focused attention, an element of many methods of meditation,[174] may have contributed to the latest phases of human biological evolution.[175] Some of the earliest references to meditation are found in the Hindu Vedas of India.[173] Wilson translates the most famous Vedic mantra "Gayatri" as: "We meditate on that desirable light of the divine Savitri, who influences our pious rites" (Rigveda : Mandala-3, Sukta-62, Rcha-10). Around the 6th to 5th centuries BCE, other forms of meditation developed via Confucianism and Taoism in China as well as Hinduism, Jainism, and early Buddhism in Nepal and India.[173]

In the Roman Empire, by 20 BCE Philo of Alexandria had written on some form of "spiritual exercises" involving attention (prosoche) and concentration[176] and by the 3rd century Plotinus had developed meditative techniques.

The Pāli Canon, which dates to 1st century BCE considers Buddhist meditation as a step towards liberation.[177] By the time Buddhism was spreading in China, the Vimalakirti Sutra which dates to 100 CE included a number of passages on meditation, clearly pointing to Zen (known as Chan in China, Thiền in Vietnam, and Seon in Korea).[178] The Silk Road transmission of Buddhism introduced meditation to other Asian countries, and in 653 the first meditation hall was opened in Singapore.[179] Returning from China around 1227, Dōgen wrote the instructions for zazen.[180][181]

The Islamic practice of Dhikr had involved the repetition of the 99 Names of God since the 8th or 9th century.[147][148] By the 12th century, the practice of Sufism included specific meditative techniques, and its followers practiced breathing controls and the repetition of holy words.[150] Interactions with Indians, Nepalese or the Sufis may have influenced the Eastern Christian meditation approach to hesychasm, but this can not be proved.[182][183] Between the 10th and 14th centuries, hesychasm was developed, particularly on Mount Athos in Greece, and involves the repetition of the Jesus prayer.[184]

Western Christian meditation contrasts with most other approaches in that it does not involve the repetition of any phrase or action and requires no specific posture. Western Christian meditation progressed from the 6th century practice of Bible reading among Benedictine monks called Lectio Divina, i.e. divine reading. Its four formal steps as a "ladder" were defined by the monk Guigo II in the 12th century with the Latin terms lectio, meditatio, oratio, and contemplatio (i.e. read, ponder, pray, contemplate). Western Christian meditation was further developed by saints such as Ignatius of Loyola and Teresa of Avila in the 16th century.[185][186][187][188]

Secular forms of meditation were introduced in India in the 1950s as a modern form of Hindu meditative techniques and arrived in Australia in the late 1950s[189] and, the United States and Europe in the 1960s. Rather than focusing on spiritual growth, secular meditation emphasizes stress reduction, relaxation and self-improvement.[173][190] Both spiritual and secular forms of meditation have been subjects of scientific analyses. Research on meditation began in 1931, with scientific research increasing dramatically during the 1970s and 1980s.[191] Since the beginning of the '70s more than a thousand studies of meditation in English have been reported.[191] However, after 60 years of scientific study, the exact mechanism at work in meditation remains unclear.[173]

Modern dissemination in the west

Methods of meditation have been cross-culturally disseminated at various times throughout history, such as Buddhism going to East Asia, and Sufi practices going to many Islamic societies. Of special relevance to the modern world is the dissemination of meditative practices since the late 19th century, accompanying increased travel and communication among cultures worldwide. Most prominent has been the transmission of numerous Asian-derived practices to the West. In addition, interest in some Western-based meditative practices has also been revived,[192] and these have been disseminated to a limited extent to Asian countries.[193] Also evident is some extent of influence over Enlightenment thinking through Denis Diderot's Encyclopédie, although he states, "I find that a meditation practitioner is often quite useless and that a contemplation practitioner is always insane".[194]

Ideas about Eastern meditation had begun "seeping into American popular culture even before the American Revolution through the various sects of European occult Christianity",[33]:3 and such ideas "came pouring in [to America] during the era of the transcendentalists, especially between the 1840s and the 1880s."[33]:3 The following decades saw further spread of these ideas to America:

The World Parliament of Religions, held in Chicago in 1893, was the landmark event that increased Western awareness of meditation. This was the first time that Western audiences on American soil received Asian spiritual teachings from Asians themselves. Thereafter, Swami Vivekananda... [founded] various Vedanta ashrams... Anagarika Dharmapala lectured at Harvard on Theravada Buddhist meditation in 1904; Abdul Baha ... [toured] the US teaching the principles of Bahai, and Soyen Shaku toured in 1907 teaching Zen...[33]:4

More recently, in the 1960s, another surge in Western interest in meditative practices began. Observers have suggested many types of explanations for this interest in Eastern meditation and revived Western contemplation. Thomas Keating, a founder of Contemplative Outreach, wrote that "the rush to the East is a symptom of what is lacking in the West. There is a deep spiritual hunger that is not being satisfied in the West."[195]:31 Daniel Goleman, a scholar of meditation, suggested that the shift in interest from "established religions" to meditative practices "is caused by the scarcity of the personal experience of these [meditation-derived] transcendental states – the living spirit at the common core of all religions."[15]:xxiv

Another suggested contributing factor is the rise of communist political power in Asia, which "set the stage for an influx of Asian spiritual teachers to the West",[33]:7 oftentimes as refugees.[196]

Meditation in the workplace

A 2010 review of the literature on spirituality and performance in organizations found an increase in corporate meditation programs.[197]

As of 2016 around a quarter of U.S. employers were using stress reduction initiatives.[198][199] The goal was to help reduce stress and improve reactions to stress. Aetna now offers its program to its customers. Google also implements mindfulness, offering more than a dozen meditation courses, with the most prominent one, "Search Inside Yourself", having been implemented since 2007.[199] General Mills offers the Mindful Leadership Program Series, a course which uses a combination of mindfulness meditation, yoga and dialog with the intention of developing the mind's capacity to pay attention.[199]

Research on meditation

Research on the processes and effects of meditation is a subfield of neurological research.[4] Modern scientific techniques, such as fMRI and EEG, were used to observe neurological responses during meditation.[200] Since the 1950s, hundreds of studies on meditation have been conducted, though the overall methological quality of meditation research is poor, yielding unreliable results.[201]

Since the 1970s, clinical psychology and psychiatry have developed meditation techniques for numerous psychological conditions.[202] Mindfulness practice is employed in psychology to alleviate mental and physical conditions, such as reducing depression, stress, and anxiety.[4][203][204] Mindfulness is also used in the treatment of drug addiction.[205] Studies demonstrate that meditation has a moderate effect to reduce pain.[4] There is insufficient evidence for any effect of meditation on positive mood, attention, eating habits, sleep, or body weight.[4]

A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of meditation on empathy, compassion, and prosocial behaviors found that meditation practices had small to medium effects on self-reported and observable outcomes, concluding that such practices can "improve positive prosocial emotions and behaviors".[206]

Preliminary studies showed a potential relationship between meditation and job performance, resulting from cognitive and social effects.[207][208]

Concerns have been raised on the quality of much meditation research,[209][210] including the particular characteristics of individuals who tend to participate.[211]

Differences in effects of different methods

Evidence from neuroimaging studies suggests that the categories of meditation, as defined by how they direct attention, appear to generate different brainwave patterns.[38][53] Evidence also suggests that using different focus objects during meditation may generate different brainwave patterns.[212]

Prevalence of meditation

The 2012 US National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) (n = 34,525), found 8.0% of US adults used meditation,[213] with lifetime and 12-month prevalence of meditation use of 5.2% and 4.1% respectively.[214] In the 2017 survey meditation use among workers was 9.9% (up from 8.0% in 2002).[215]

Meditation, religion and drugs

Many major traditions in which meditation is practiced, such as Buddhism[216] and Hinduism,[217] advise members not to consume intoxicants, while others, such as the Rastafarian movements and Native American Church, view drugs as integral to their religious lifestyle.

The fifth of the five precepts of the Pancasila, the ethical code in the Theravada and Mahayana Buddhist traditions, states that adherents must: "abstain from fermented and distilled beverages that cause heedlessness."[218]

On the other hand, the ingestion of psychoactives has been a central feature in the rituals of many religions, in order to produce altered states of consciousness. In several traditional shamanistic ceremonies, drugs are used as agents of ritual. In the Rastafari movement, cannabis is believed to be a gift from Jah and a sacred herb to be used regularly, while alcohol is considered to debase man. Native Americans use peyote, as part of religious ceremony, continuing today.[219] In India, the soma drink has a long history of use alongside prayer and sacrifice, and is mentioned in the Vedas.

During the 1960s and 70s, both eastern meditation traditions and psychedelics, such as LSD, became popular in America, and it was suggested that LSD use and meditation were both means to the same spiritual/existential end.[220] Many practitioners of eastern traditions rejected this idea, including many who had tried LSD themselves. In The Master Game, Robert S de Ropp writes that the "door to full consciousness" can be glimpsed with the aid of substances, but to "pass beyond the door" requires yoga and meditation. Other authors, such as Rick Strassman, believe that the relationship between religious experiences reached by way of meditation and through the use of psychedelic drugs deserves further exploration.[221]

Criticism

Mindfulness meditation, in its modern form, is regarded by psychologist Thomas Joiner to have been "corrupted" for commercial gain by self-help celebrities, and he suggests that it encourages narcissistic and self-obsessed mindsets which can be unhealthy.[222][223]

There has been some reporting of cases where meditating correlated with negative experiences for the meditator.[224][225][226][227]

See also

References

- ↑ "Definition of meditate". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. 18 December 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ↑ For the 14th Dalai Lama the aim of meditation is "to maintain a very full state of alertness and mindfulness, and then try to see the natural state of your consciousness."

- ↑ "Meditation: In Depth". NCCIH.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Goyal, M; Singh, S; Sibinga, E. M; Gould, N. F; Rowland-Seymour, A; Sharma, R; Berger, Z; Sleicher, D; Maron, D. D; Shihab, H. M; Ranasinghe, P. D; Linn, S; Saha, S; Bass, E. B; Haythornthwaite, J. A (2014). "Meditation Programs for Psychological Stress and Well-being: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA Internal Medicine. 174 (3): 357–368. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13018. PMC 4142584. PMID 24395196.

- 1 2 Shaner, Lynne; Kelly, Lisa; Rockwell, Donna; Curtis, Devorah (2016). "Calm Abiding". Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 57: 98. doi:10.1177/0022167815594556.

- ↑ Campos, Daniel; Cebolla, Ausiàs; Quero, Soledad; Bretón-López, Juana; Botella, Cristina; Soler, Joaquim; García-Campayo, Javier; Demarzo, Marcelo; Baños, Rosa María (2016). "Meditation and happiness: Mindfulness and self-compassion may mediate the meditation–happiness relationship". Personality and Individual Differences. 93: 80–85. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.08.040. hdl:10234/157867.

- ↑ An universal etymological English dictionary 1773, London, by Nathan Bailey ISBN 1-00-237787-0. Note: from the 1773 edition on Google books, not earlier editions.

- ↑ Terje Stordalen, "Ancient Hebrew Meditative Recitation", in Halvor Eifring (ed.), Meditation in Judaism, Christianity and Islam: Cultural Histories, 2013, ISBN 978-1441122148 pages 17-31

- ↑ Christian spirituality: themes from the tradition by Lawrence S. Cunningham, Keith J. Egan 1996 ISBN 0-8091-3660-0 page 88

- ↑ The Oblate Life by Gervase Holdaway, 2008 ISBN 0-8146-3176-2 page 115

- ↑ Besides Lectio and Yoga, examples include Herbert Benson's (1975) Relaxation Response ISBN 0-380-00676-6, Jon Kabat-Zinn's (1990) Full Catastrophe Living ISBN 0-385-29897-8, and Eknath Easwaran's (1978) Passage Meditation ISBN 978-1-58638-026-7

- 1 2 Feuerstein, Georg. "Yoga and Meditation (Dhyana)." Moksha Journal. Issue 1. 2006. ISSN 1051-127X, OCLC 21878732

- ↑ The verb root "dhyai" is listed as referring to "contemplate, meditate on" and "dhyāna" is listed as referring to "meditation; religious contemplation" on page 134 of Macdonell, Arthur Anthony (1971) [Reprinted from 1929]. A practical Sanskrit dictionary with transliteration, accentuation and etymological analysis throughout. London: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Mirahmadi, Sayyid Nurjan; Naqshbandi, Muhammad Nazim Adil al-Haqqani; Kabbani, Muhammad Hisham; Mirahmadi, Hedieh (2005). The healing power of sufi meditation. Fenton, MI: Naqshbandi Haqqani Sufi Order of America. ISBN 978-1-930409-26-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Goleman, Daniel (1988). The meditative mind: The varieties of meditative experience. New York: Tarcher. ISBN 978-0-87477-833-5.

- ↑ Jonathan Shear, ed. (2006). The experience of meditation: Experts introduce the major traditions. St. Paul, MN: Paragon House. ISBN 978-1-55778-857-3.

- ↑ Joel Stein (2003). "Just say Om". Time. 162 (5): 48–56. In the print edition (pp. 54-55), the "Through the Ages" box describes "Christian Meditation", "Cabalistic (Jewish) Meditation", "Muslim Meditation", and others.

- ↑ Jean L. Kristeller (2010). "Spiritual engagement as a mechanism of change in mindfulness- and acceptance-based therapies". In Ruth A. Baer; Kelly G. Wilson. Assessing mindfulness and acceptance processes in clients: Illuminating the theory and practice of change. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger. pp. 152–184. ISBN 978-1-57224-694-2. . Page 161 states "In Christianity, the term 'contemplation' is parallel to the term 'meditation' as it has entered contemporary usage"

- ↑ Halvor Eifring, "Meditation in Judaism, Christianity and Islam: Technical Aspects of Devotional Practices", in Halvor Eifring (ed.), Meditation in Judaism, Christianity and Islam: Cultural Histories, 2013, ISBN 978-1441122148 pages 1-16.

- ↑ Mary Carroll (2005). "Divine therapy: Teaching reflective and meditative practices". Teaching Theology and Religion. 8 (4): 232–238. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9647.2005.00249.x.

- ↑ "meditate - Definition of meditate in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries - English.

- ↑ "meditation Meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary". dictionary.cambridge.org.

- 1 2 "Lutz A., Dunne J.D., Davidson R.J. Meditation and the Neuroscience of Consciousness: an Introduction in Cambridge Handbook of Consciousness edited by Zelazo P., Moscovitch M. and Thompson E. (2007)" (PDF).

- ↑ "members were chosen on the basis of their publication record of research on the therapeutic use of meditation, their knowledge of and training in traditional or clinically developed meditation techniques, and their affiliation with universities and research centers.. Each member had specific expertise and training in at least one of the following meditation practices: kundalini yoga, Transcendental Meditation, relaxation response, mindfulness-based stress reduction, and vipassana meditation" (Bond, Ospina et al., 2009, p. 131); their views were combined using "the Delphi technique... a method of eliciting and refining group judgments to address complex problems with a high level of uncertainty" (p. 131).

- 1 2 3 Kenneth Bond; Maria B. Ospina; Nicola Hooton; Liza Bialy; Donna M. Dryden; Nina Buscemi; David Shannahoff-Khalsa; Jeffrey Dusek; Linda E. Carlson (2009). "Defining a complex intervention: The development of demarcation criteria for "meditation"". Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 1 (2): 129–137. doi:10.1037/a0015736.

- ↑ The full quotation from Bond, Ospina et al. (2009, p. 135) reads: "It is plausible that meditation is best thought of as a natural category of techniques best captured by 'family resemblances' (Wittgenstein, 1968) or by the related 'prototype' model of concepts (Rosch, 1973; Rosch & Mervin, 1975)."

- 1 2 Roger Walsh & Shauna L. Shapiro (2006). "The meeting of meditative disciplines and western psychology: A mutually enriching dialogue" (Submitted manuscript). American Psychologist. 61 (3): 227–239. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.61.3.227. ISSN 0003-066X. PMID 16594839.

- 1 2 B. Rael Cahn; John Polich (2006). "Meditation states and traits: EEG, ERP, and neuroimaging studies". Psychological Bulletin. 132 (2): 180–211. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.180. ISSN 0033-2909. PMID 16536641.

- 1 2 R. Jevning; R. K. Wallace; M. Beidebach (1992). "The physiology of meditation: A review: A wakeful hypometabolic integrated response". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 16 (3): 415–424. doi:10.1016/S0149-7634(05)80210-6. PMID 1528528.

- ↑ Number of citations in PsycINFO: 254 for Walsh & Shapiro, 2006 (26 August 2018); 561 for Cahn & Polich, 2006 (26 August 2018); 83 for Jevning et al. (1992) (26 August 2018).

- 1 2 Lutz, Dunne and Davidson, "Meditation and the Neuroscience of Consciousness: An Introduction" in The Cambridge handbook of consciousness by Philip David Zelazo, Morris Moscovitch, Evan Thompson, 2007 ISBN 0-521-85743-0 page 499-551 (proof copy) (NB: pagination of published was 499-551 proof was 497-550). Archived March 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 "John Dunne's speech". Archived from the original on November 20, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Eugene Taylor (1999). Michael Murphy; Steven Donovan; Eugene Taylor, eds. "Introduction". The Physical and Psychological Effects of Meditation: A Review of Contemporary Research with a Comprehensive Bibliography 1931-1996: 1–32.

- ↑ Robert Ornstein (1972, originally published 1971), in: Naranjo and Orenstein, On the Psychology of Meditation. New York: Viking. LCCN 76149720

- ↑ This does not mean that all meditation seeks to take a person beyond all thought processes, only those processes that are sometimes referred to as "discursive" or "logical" (see Shapiro, 1982/1984; Bond, Ospina, et al., 2009; Appendix B, pp. 279-282 in Ospina, Bond, et al., 2007).

- ↑ An influential definition by Shapiro (1982; republished 1984, 2008) states that "meditation refers to a family of techniques which have in common a conscious attempt to focus attention in a nonanalytical way and an attempt not to dwell on discursive, ruminating thought" (p. 6, italics in original); the term "discursive thought" has long been used in Western philosophy, and is often viewed as a synonym to logical thought (Rappe, Sara (2000). Reading neoplatonism : Non-discursive thinking in the texts of plotinus, proclus, and damascius. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-65158-5. ).

- ↑ Bond, Ospina et al. (2009) – see fuller discussion elsewhere on this page -- report that 7 expert scholars who had studied different traditions of meditation agreed that an "essential" component of meditation "Involves logic relaxation: not 'to intend' to analyze the possible psychophysical effects, not 'to intend' to judge the possible results, not 'to intend' to create any type of expectation regarding the process" (p. 134, Table 4). In their final consideration, all 7 experts regarded this feature as an "essential" component of meditation; none of them regarded it as merely "important but not essential" (p. 234, Table 4). (This same result is presented in Table B1 in Ospina, Bond, et al., 2007, p. 281)

- 1 2 3 Lutz, Antoine; Slagter, Heleen A.; Dunne, John D.; Davidson, Richard J. (April 2008). "Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 12 (4): 163–169. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2008.01.005. PMC 2693206. PMID 18329323.

The term ‘meditation’ refers to a broad variety of practices...In order to narrow the explanandum to a more tractable scope, this article uses Buddhist contemplative techniques and their clinical secular derivatives as a paradigmatic framework (see e.g., 9,10 or 7,9 for reviews including other types of techniques, such as Yoga and Transcendental Meditation). Among the wide range of practices within the Buddhist tradition, we will further narrow this review to two common styles of meditation, FA and OM (see box 1–box 2), that are often combined, whether in a single session or over the course of practitioner's training. These styles are found with some variation in several meditation traditions, including Zen, Vipassanā and Tibetan Buddhism (e.g. 7,15,16)....The first style, FA meditation, entails voluntary focusing attention on a chosen object in a sustained fashion. The second style, OM meditation, involves non-reactively monitoring the content of experience from moment to moment, primarily as a means to recognize the nature of emotional and cognitive patterns

- ↑ The full quote from Bond, Ospina et al. (2009, p. 130) reads: "The differences and similarities among these techniques is often explained in the Western meditation literature in terms of the direction of mental attention (Koshikawa & Ichii, 1996; Naranjo, 1971; Orenstein, 1971): A practitioner can focus intensively on one particular object (so-called concentrative meditation), on all mental events that enter the field of awareness (so-called mindfulness meditation), or both specific focal points and the field of awareness (Orenstein, 1971)."

- ↑ Easwaran, Eknath (10 September 2018). The Bhagavad Gita: (Classics of Indian Spirituality). Nilgiri Press. ISBN 9781586380199 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Single-pointed concentration (samadhi) is a meditative power that is useful in either of these two types of meditation. However, in order to develop samadhi itself we must cultivate principally concentration meditation. In terms of practice, this means that we must choose an object of concentration and then meditate single-pointedly on it every day until the power of samadhi is attained." lywa (2 April 2015). "Developing Single-pointed Concentration".

- ↑ "Site is under maintenance". meditation-research.org.uk.

- 1 2 "Mindful Breathing (Greater Good in Action)". ggia.berkeley.edu.

- ↑ Shonin, Edo; Van Gordon, William (2016). "Experiencing the Universal Breath: A Guided Meditation". Mindfulness. 7 (5): 1243. doi:10.1007/s12671-016-0570-4.

- 1 2 Perez-De-Albeniz, Alberto; Jeremy Holmes (March 2000). "Meditation: concepts, effects and uses in therapy". International Journal of Psychotherapy. 5 (1): 49–59. doi:10.1080/13569080050020263. Retrieved 2007-08-23.

- ↑ "Deepening Calm-Abiding - The Nine Stages of Abiding". terebess.hu.

- ↑ Dorje, Ogyen Trinley. "Calm Abiding".

- ↑ "What kind of meditation is Headspace?". Help Center.

- ↑ Manocha, Ramesh; Black, Deborah; Wilson, Leigh (10 September 2018). "Quality of Life and Functional Health Status of Long-Term Meditators". Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012: 1–9. doi:10.1155/2012/350674. PMC 3352577. PMID 22611427.

- ↑ "There might be a depth of meditation where thinking ceases. This is a refined, refreshing and nourishing state of consciousness. But it is not the goal." Kirsten Kratz, "Calm and kindness" talk, Gaia House, 03/2013

- ↑ "Meditation". 21 June 2011.

- ↑ "Huineng (Hui-neng) (638—713)". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- 1 2 Fred Travis; Jonathan Shear (2010). "Focused attention, open monitoring and automatic self-transcending: Categories to organize meditations from Vedic, Buddhist and Chinese traditions". Consciousness and Cognition. 19 (4): 1110–8. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2010.01.007. PMID 20167507.

- ↑ "BBC - Religions - Buddhism: Meditation".

- ↑ "Judson Brewer". University of Massachusetts Medical School.

- ↑ "The Dalai Lama Reveals How to Practice Meditation Properly - Hack Spirit". 3 May 2017.

- ↑ "Dalai Lama on Analytic Meditation And How It Helps Cultivate Positivity".

- ↑ "10% Happier with Dan Harris by ABC News on Apple Podcasts".

- ↑ Bradley, Alice. "How to Find Real Love, With Sharon Salzberg".

- ↑ Pulse. "12 ways to be happier at work in less than 10 minutes".

- ↑ "10% Happier with Dan Harris by ABC News on Apple Podcasts". Apple Podcasts.

- ↑ "Guided Meditations on the Stages of the Path eBook: Thubten Chodron, H.H. the Dalai Lama, Dalai Lama: Amazon.co.uk: Kindle Store". www.amazon.co.uk.

- ↑ "Meditations on kindness, gratitude and love".

- ↑ https://www.amazon.co.uk/Chakra-Meditation-Swami-Saradananda/dp/1907486909

- ↑ Meditation, Path to the Deepest Self, Dorling Kindersley, 2002. ISBN 978-0-7894-8333-1

- ↑ "The Daily Habit Of These Outrageously Successful People". 5 July 2013.

- ↑ Mindfulness#Meditation method

- 1 2 3 News, A. B. C. (27 July 2016). "Neuroscientist Says Dalai Lama Gave Him 'a Total Wake-Up Call'". ABC News.

- ↑ "How Humankind Could Become Totally Useless". Time. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ Kaul, P; Passafiume, J; Sargent, C. R; O'Hara, B. F (2010). "Meditation acutely improves psychomotor vigilance, and may decrease sleep need". Behavioral and Brain Functions. 6: 47. doi:10.1186/1744-9081-6-47 (inactive 2018-09-10). PMC 2919439. PMID 20670413.

- ↑ "Questions & Answers - Dhamma Giri - Vipassana International Academy". www.giri.dhamma.org.

- ↑ "Brahmamuhurta: The best time for meditation - Times of India".

- ↑ Ng, Teng-Kuan (2018). "Pedestrian Dharma: Slowness and Seeing in Tsai Ming-Liang's Walker". Religions. 9 (7): 200. doi:10.3390/rel9070200.

- 1 2 Mysteries of the Rosary by Stephen J. Binz 2005 ISBN 1-58595-519-1 page 3

- 1 2 The everything Buddhism book by Jacky Sach 2003 ISBN 978-1-58062-884-6 page 175

- ↑ For a general overview see Beads of Faith: Pathways to Meditation and Spirituality Using Rosaries, Prayer Beads, and Sacred Words by Gray Henry, Susannah Marriott 2008 ISBN 1-887752-95-1

- 1 2 Meditation and Mantras by Vishnu Devananda 1999 ISBN 81-208-1615-3 pages 82–83

- ↑ Acharya Tulsi Key (1995). "01.01 Traditions of shramanas". Bhagwan Mahavira. JVB, Ladnun, India. Retrieved 2009-09-27.

- ↑ Sadhvi Vishrut Vibha Key (2007). "1 History and Tradition". Introduction to Jainism. JVB, Ladnun, India.

- ↑ Acharya Tulsi Key (1995). "04.04 accomplishment of sadhana". Bhagwan Mahavira. JVB, Ladnun, India. Retrieved 2009-09-27.

- ↑ Ahimsa – The Science Of Peace by Surendra Bothra 1987

- ↑ "Achraya Bhadrabahu Swami". Retrieved 2010-07-20.

- ↑ Jain Yoga by Acharya Mahapragya 2004

- ↑ Acharya Mahapragya (2004). "Foreword". Jain Yog. Aadarsh Saahitya Sangh.

- ↑ Acharya Tulsi (2004). "blessings". Sambodhi. Aadarsh Saahitya Sangh.

- 1 2 Dr. Rudi Jansma; Dr. Sneh Rani Jain Key (2006). "07 Yoga and Meditation (2)". Introduction To Jainism. Prakrit Bharti Academy, jaipur, India. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- ↑ Dr. Rudi Jansma; Dr. Sneh Rani Jain Key (2006). "07 Yoga and Meditation (2)". Introduction To Jainism. Prakrit Bharti Academy, jaipur, India. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ↑ Muni Kishan Lal Key (2007). Preksha Dhyana: Yogic Exercises. Jain Vishva Bharati. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ↑ "Preksha Meditation". Preksha International. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ↑ https://evo4soul.com/about/

- ↑ https://evo4soul.com/evo4soul/

- ↑ For instance, Kamalashila (2003), p. 4, states that Buddhist meditation "includes any method of meditation that has Enlightenment as its ultimate aim." Likewise, Bodhi (1999) writes: "To arrive at the experiential realization of the truths it is necessary to take up the practice of meditation.... At the climax of such contemplation the mental eye ... shifts its focus to the unconditioned state, Nibbana...." A similar although in some ways slightly broader definition is provided by Fischer-Schreiber et al. (1991), p. 142: "Meditation – general term for a multitude of religious practices, often quite different in method, but all having the same goal: to bring the consciousness of the practitioner to a state in which he can come to an experience of 'awakening,' 'liberation,' 'enlightenment.'" Kamalashila (2003) further allows that some Buddhist meditations are "of a more preparatory nature" (p. 4).

- ↑ The Pāli and Sanskrit word bhāvanā literally means "development" as in "mental development." For the association of this term with "meditation," see Epstein (1995), p. 105; and, Fischer-Schreiber et al. (1991), p. 20. As an example from a well-known discourse of the Pali Canon, in "The Greater Exhortation to Rahula" (Maha-Rahulovada Sutta, MN 62), Ven. Sariputta tells Ven. Rahula (in Pali, based on VRI, n.d.): ānāpānassatiṃ, rāhula, bhāvanaṃ bhāvehi. Thanissaro (2006) translates this as: "Rahula, develop the meditation [bhāvana] of mindfulness of in-&-out breathing." (Square-bracketed Pali word included based on Thanissaro, 2006, end note.)

- ↑ See, for example, Rhys Davids & Stede (1921-25), entry for "jhāna1"; Thanissaro (1997); as well as, Kapleau (1989), p. 385, for the derivation of the word "zen" from Sanskrit "dhyāna". Pāli Text Society Secretary Rupert Gethin, in describing the activities of wandering ascetics contemporaneous with the Buddha, wrote:

- [T]here is the cultivation of meditative and contemplative techniques aimed at producing what might, for the lack of a suitable technical term in English, be referred to as "altered states of consciousness". In the technical vocabulary of Indian religious texts such states come to be termed "meditations" ([Skt.:] dhyāna / [Pali:] jhāna) or "concentrations" (samādhi); the attainment of such states of consciousness was generally regarded as bringing the practitioner to deeper knowledge and experience of the nature of the world. (Gethin, 1998, p. 10.)

- ↑ Goldstein (2003) writes that, in regard to the Satipatthana Sutta, "there are more than fifty different practices outlined in this Sutta. The meditations that derive from these foundations of mindfulness are called vipassana..., and in one form or another – and by whatever name – are found in all the major Buddhist traditions" (p. 92). The forty concentrative meditation subjects refer to Visuddhimagga's oft-referenced enumeration. Regarding Tibetan visualizations, Kamalashila (2003), writes: "The Tara meditation ... is one example out of thousands of subjects for visualization meditation, each one arising out of some meditator's visionary experience of enlightened qualities, seen in the form of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas" (p. 227).

- ↑ Examples of contemporary school-specific "classics" include, from the Theravada tradition, Nyanaponika (1996) and, from the Zen tradition, Kapleau (1989).

- ↑ These definitions of samatha and vipassana are based on the "Four Kinds of Persons Sutta" (AN 4.94). This article's text is primarily based on Bodhi (2005), pp. 269–70, 440 n. 13. See also Thanissaro (1998d).

- ↑ See, for instance, AN 2.30 in Bodhi (2005), pp. 267-68, and Thanissaro (1998e).

- ↑ "Mindfulness-Based Programs". University of Massachusetts Medical School.

- 1 2 Flood, Gavin (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 94–95. ISBN 978-0-521-43878-0.

- ↑ Alexander Wynne, The Origin of Buddhist Meditation. Routledge 2007, page 51. The earliest reference is actually in the Mokshadharma, which dates to the early Buddhist period.

- ↑ The Katha Upanishad describes yoga, including meditation. On meditation in this and other post-Buddhist Hindu literature see Randall Collins, The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Harvard University Press, 2000, page 199.

- ↑ Shri, Jnaneshvar (1978). Jnaneshvari. New York: State University of New York Press. pp. 114–152. ISBN 978-0887064883.

- ↑ "Jnanesvar and Nivritti Nath - The Great Natha Siddhas". Retrieved 2018-05-25.

- ↑ Sharma, Suresh (2004). Cultural and Religious Heritage of India: Sikhism. Mittal Publications. p. 7. ISBN 9788170999614.

- ↑ Parashar, M. (2005). Ethics And The Sex-King. AuthorHouse. p. 592. ISBN 9781463458133.

- ↑ Duggal, Kartar (1980). The Prescribed Sikh Prayers (Nitnem). Abhinav Publications. p. 20. ISBN 9788170173779.

- ↑ Singh, Nirbhai (1990). Philosophy of Sikhism: Reality and Its Manifestations. Atlantic Publishers & Distribution. p. 105.

- ↑ Kohn, Livia (2008), "Meditation and visualization," in The Encyclopedia of Taoism, ed. by Fabrizio Pregadio, p. 118.

- ↑ Harper, Donald; Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (2007) [First published in 1999]. The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 BC. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. p. 880. ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8.

- ↑ Roth, Harold D. (1999), Original Tao: Inward Training (Nei-yeh) and the Foundations of Taoist Mysticism, Columbia University Press, p. 92.

- ↑ Mair, Victor H., tr. (1994), Wandering on the Way: Early Taoist Tales and Parables of Chuang Tzu, Bantam Books, p. 64.

- 1 2 "Prayer, Meditation, and Fasting". Bahá'í International Community. 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-08-05. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- 1 2 3 4 Smith, Peter (2000). "Meditation". A concise encyclopedia of the Bahá'í Faith. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. pp. 243–44. ISBN 978-1-85168-184-6.

- ↑ Smith, Peter (2000). "Prayer". A concise encyclopedia of the Bahá'í Faith. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. p. 274. ISBN 978-1-85168-184-6.

- ↑ Effendi, Shoghi (1983). Hornby, Helen, ed. Lights of Guidance: A Bahá'í Reference File. Bahá'í Publishing Trust, New Delhi, India. p. 506. ISBN 978-81-85091-46-4.

- ↑ Effendi, Shoghi (1973). Directives from the Guardian. Hawaii Bahá'í Publishing Trust. p. 28.

- ↑ The history and varieties of Jewish meditation by Mark Verman 1997 ISBN 978-1-56821-522-8 page 1

- ↑ Jacobs, L. (1976) Jewish Mystical Testimonies, Jerusalem, Keter Publishing House Jerusalem Ltd.

- ↑ Kaplan, A. (1978) Meditation and the Bible, Maine, Samuel Weiser Inc., p 101.

- ↑ The history and varieties of Jewish meditation by Mark Verman 1997 ISBN 978-1-56821-522-8 page 45

- 1 2 3 Kaplan, A. (1985) Jewish Meditation: A Practical Guide, New York Schocken Books.

- ↑ Scholem, Gershom Gerhard (1961). Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism. Schocken Books. p. 34. ISBN 9780805210422.

- ↑ Kaplan, A. (1982) Meditation and Kabbalah, Maine, Samuel Weiser, Inc.

- ↑ Matt, D.C. (1996) The Essential Kabbalah: The Heart of Jewish Mysticism, San Francisco, HarperCollins.

- ↑ Kaplan, A. (1978) op cit p2

- ↑ Kaplan, (1982) op cit, p13

- ↑ Claussen, Geoffrey. "The Practice of Musar". Conservative Judaism 63, no. 2 (2012): 3-26. Retrieved June 10, 2014

- ↑ Michaelson, Jay (June 10, 2005). "Judaism, Meditation and The B-Word". The Forward.

- ↑ The Rosary: A Path Into Prayer by Liz Kelly 2004 ISBN 0-8294-2024-X pages 79 and 86

- ↑ Christian Meditation for Beginners by Thomas Zanzig, Marilyn Kielbasa 2000, ISBN 0-88489-361-8 page 7

- ↑ An introduction to Christian spirituality by F. Antonisamy, 2000 ISBN 81-7109-429-5 pages 76-77

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-06-01. Retrieved 2017-06-19.

- ↑ "The Holy Rosary". www.theholyrosary.org.

- ↑ "The Rosary as a Tool for Meditation by Liz Kelly". www.loyolapress.com.

- ↑ Christian Meditation by Edmund P. Clowney, 1979 ISBN 1-57383-227-8 page 12

- ↑ Christian Meditation by Edmund P. Clowney, 1979 ISBN 1-57383-227-8 pages 12-13

- ↑ The encyclopedia of Christianity, Volume 3 by Erwin Fahlbusch, Geoffrey William Bromiley 2003 ISBN 90-04-12654-6 page 488

- ↑ EWTN: Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith Letter on certain aspects of Christian meditation (in English), October 15, 1989

- ↑ Los Angeles Times, February 8, 2003, New Age Beliefs Aren't Christian, Vatican Finds

- ↑ "Vatican sounds New Age alert". 4 February 2003 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ↑ "PRESENTATIONS OF HOLY SEE'S DOCUMENT ON NEW AGE". www.vatican.va.