Digambara

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

|

Jain prayers |

|

Ethics |

|

Major sects |

|

Festivals |

|

|

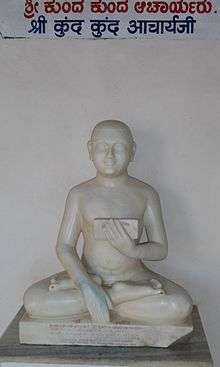

Digambara (/dɪˈɡʌmbərə/; "sky-clad") is one of the two major schools of Jainism, the other being Śvētāmbara (white-clad). The word Digambara (Sanskrit) is a combination of two words: dig (directions) and ambara (sky), referring to those whose garments are of the element that fills the four quarters of space. Digambara monks do not wear any clothes. The monks carry picchi, a broom made up of fallen peacock feathers (for clearing the place before walking or sitting), kamandalu (a water container made of wood), and shastra (scripture). One of the most important scholar-monks of Digambara tradition was Kundakunda. He authored Prakrit texts such as the Samayasāra and the Pravacanasāra. Other prominent Acharyas of this tradition were, Virasena (author of a commentary on the Dhavala), Samantabhadra and Siddhasena Divakara. The Satkhandagama and Kasayapahuda have major significance in the Digambara tradition.

History

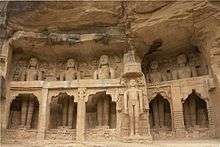

Relics found from Harrapan excavations such as seals depicting Kayotsarga posture, idols in Padmasana and a nude bust of red limestone, give insight into the antiquity of the Digambara tradition.[1] The presence of gymnosophists (naked philosophers) in Greek records as early as the fourth century BC, supports the claim of the Digambaras that they have preserved the ancient Śramaṇa practice.[2]

Dundas talks about the archeological evidences which indicate that Jain monks moved from the practice of total nudity towards wearing clothes in later period. Ancient Tirthankara statues found in Mathura are naked. The oldest Tirthankara statue wearing a cloth is dated in 5th century CE.[3] Digamabara statues of tirthankara belonging to Gupta period has half-closed eyes.[4]

Lineage

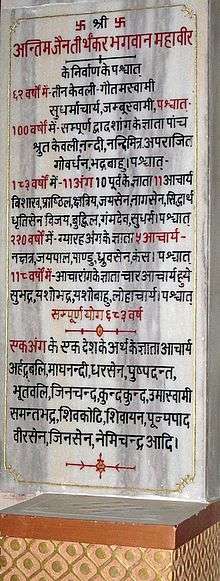

According to Digambara texts, after liberation of the Lord Mahavira, three Anubaddha Kevalīs attained Kevalajñāna (omniscience) sequentially – Gautama Gaņadhara, Acharya Sudharma, and Jambusvami in next 62 years.[5] During the next hundred years, five Āchāryas had complete knowledge of the scriptures, as such, called Śruta Kevalīs, the last of them being Āchārya Bhadrabahu.[6][7] Spiritual lineage of heads of monastic orders is known as Pattavali.[8] Digambara tradition consider Dharasena to be the 33rd teacher in succession of Gautama, 683 years after the nirvana of Mahavira.[9]

| Acharyas | Time period | Known for |

|---|---|---|

| Bhadrabahu | 3rd century B.C.E. | Last Shruta Kevalin and Chandragupta Maurya's spiritual teacher[6] |

| Kundakunda | 1st century B.C.E.- 1st century C.E. | Author of Samayasāra, Niyamasara, Pravachansara, Barah anuvekkha[10] |

| Umaswami | 2nd century C.E. | Author of Tattvartha Sutra (canon on science and ethics) |

| Samantabhadra | 2nd century C.E. | Author of Ratnakaranda śrāvakācāra, Aptamimamsa |

| Siddhasena Divakara | 5th century C.E. | Author of Sanmatitarka[11] |

| Pujyapada | 5th century C.E. | Author of Iṣṭopadeśa (Divine Sermons), a concise work of 51 verses |

| Manatunga | 6th century C.E. | Creator of famous Bhaktamara Stotra |

| Virasena | 8th-century C.E. | Mathematician and author of Dhavala[12] |

| Jinasena | 9th century C.E. | Author of Mahapurana |

| Nemichandra | 10th century C.E. | Author of Dravyasamgraha and supervised the consecration of the Gomateshwara statue. |

Practices

Monasticism

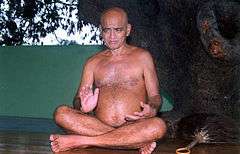

The word Digambara is a combination of two Sanskrit words: dik (दिक्) (directions) and ambara (अम्बर) (clothes), referring to those whose garments are of the element that fills the four quarters of space.[2] Digambara monks do not wear any clothes as it is considered to be parigraha (possession), which ultimately leads to attachment.[13] A Digambara monk has 28 mūla guņas (primary attributes).[14] These are: five mahāvratas (supreme vows); five samitis (regulations); pañcendriya nirodha (five-fold control of the senses); Ṣadāvaśyakas (six essential duties); and seven niyamas (rules or restrictions).[15]

| Head | Vow | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Mahavratas- Five Great Vows[16][17] |

1. Ahimsa | Not to injure any living being through actions or thoughts |

| 2. Truth | To speak only the truth and good words | |

| 3. Asteya | Not to take anything unless given | |

| 4. Brahmacharya | Celibacy in action, words and thoughts | |

| 5. Aparigraha | Renunciation of worldly things and foreign natures, external and internal | |

| Samiti- Fivefold regulation of activities[18][19] |

6. irya | To walk carefully after viewing land to the extent of four cubits (2 yards). |

| 7. bhasha | Not to criticise anyone or speak bad words | |

| 8. eshna | To accept food from a sravaka (householder) if it is free from 46 faults | |

| 9. adan-nishep | Carefulness in the handling of whatever the saint possess. | |

| 10. pratishṭapan | To dispose off the body waste at a place free from living beings. | |

| Panchindrinirodh[15] | 11–15. Fivefold control of the senses | Shedding all attachment and aversion towards the sense objects pertaining to touch (sparśana), taste (rasana), smell (ghrāṇa), sight (cakśu), and hearing (śrotra) |

| Six Essential Duties[20][15] | 16. Sāmāyika | Meditate for equanimity towards every living being |

| 17. stuti | Worship of the Tirthankaras | |

| 18. vandan | To pay obeisances to siddhas, arihantas and acharyas | |

| 19. Pratikramana | Self-censure, repentance; to drive oneself away from the multitude of karmas, virtuous or wicked, done in the past. | |

| 20. Pratikhayan | Renunciation | |

| 21. Kayotsarga | Giving up attachment to the body and meditate on soul. | |

| Niyama- Seven rules[15][21] |

22. adantdhavan | Not to use tooth powder to clean teeth |

| 23. bhushayan | Sleeping on hard ground | |

| 24. asnāna | Non-bathing | |

| 25. stithi-bhojan | Eating food in standing posture | |

| 26. ahara | To consume food and water once a day | |

| 27. keśa-lonch | To pluck hair on the head and face by hand. | |

| 28. nudity | To be nude (digambara) | |

The monks carry picchi, a broom made up of fallen peacock feathers for removing small insects without causing them injury, Kamandalu (the gourd for carrying pure, sterilized water) and shastra (scripture).[22][23] The head of all monastics is called Āchārya, while the saintly preceptor of saints is the upādhyāya.[24] The Āchārya has 36 primary attributes (mūla guņa) in addition to the 28 mentioned above.[15] The monks perform kayotsarga daily, in a rigid and immobile posture, with the arms held stiffly down, knees straight, and toes directed forward.[2] Female monastics in Digambara tradition are known as aryikas.[25] Statistically, there are more Digambara nuns, than there are monks.[26]

Worship

The Digambara Jains worship completely nude idols of tirthankaras (omniscient beings) and siddha (liberated souls). The tirthankara is represented either seated in yoga posture or standing in the Kayotsarga posture.[27]

The truly "sky-clad" (digambara) Jaina statue expresses the perfect isolation of the one who has stripped off every bond. His is an absolute "abiding in itself," a strange but perfect aloofness, a nudity of chilling majesty, in its stony simplicity, rigid contours, and abstraction.[28]

Statues

- Kizhavalavu (Keelavalavu) Sculptures

Tirthankara Parshvanatha statue, Rajasthan

Tirthankara Parshvanatha statue, Rajasthan

Literature

The Digambara sect of Jainism rejects the authority of the texts accepted by the other major sect, the Svetambaras.[29]

According to the Digambaras, Āchārya Dharasena guided two Āchāryas, Pushpadanta and Bhutabali, to put the teachings of Mahavira in written form, 683 years after the nirvana of Mahavira.[9] The two Āchāryas wrote Ṣaṭkhaṅḍāgama on palm leaves which is considered to be among the oldest known Digambara texts.[30] Āchārya Bhutabali was the last ascetic who had partial knowledge of the original Jain Agamas. Later on, some learned Āchāryas started to restore, compile and put into written words the teachings of Lord Mahavira, that were the subject matter of Agamas.[7]

Digambaras group the texts into four literary categories called anuyoga (exposition).[31] The prathmanuyoga (first exposition) contains the universal history, the karananuyoga (calculation exposition) contains works on cosmology and the charananuyoga (behaviour exposition) includes texts about proper behaviour for monks and Sravakas.[31]

Most eminent Digamabara authors include Kundakunda, Samantabhadra, Pujyapada, Jinasena, Akalanka, Vidyanandi, Somadeva and Asadhara.[32]

Sub-sects

- Jain Sangh

- Digambara

- Mula Sangh

- Great Schools

- Nandi Gana

- Balatkara Gana

- Desiya Gana

- Sena Gana

- Simha Gana

- Deva Gana

- Nandi Gana

- Other Mula Sangh branches (extinct)

- Kashtha Sangh (exists)

- Great Schools

- Present Sects

- Taran Panth

- Bispanthi

- Digambar Terapanth

- Other

- Kanji Swami Panth established by ex-Sthanakvasi monk.

- Gumanpanth

- Totapanth

- Mula Sangh

- Digambara

The Digambara tradition can be divided into two main orders viz. Mula Sangha (original community) and modern community. Mula Sangha can be further divided into orthodox and heterodox traditions. Orthodox traditions included Nandi, Sena, Simha and Deva sangha. Heterodox traditions included Dravida, Yapaniya, Kashtha and Mathura sangha.[34] Other traditions of Mula sangha include Deshiya Gana and Balatkara Gana traditions. Modern Digambara community is divided into various sub-sects viz. Terapanthi, Bispanthi, Taranpanthi (or Samayiapanthi), Gumanapanthi and Totapanthi.[35]

Digambara community was divided into Terapanthi and Bisapanthi on the acceptance of authority of Bhattaraka.[36] The Bhattarakas of Shravanabelagola and Mudbidri belong to Deshiya Gana and the Bhattaraka of Humbaj belongs to the Balatkara Gana.[37]

The Bispanth-Terapanth division among the Digambaras emerged in the 17th century in the Jaipur region: Sanganer, Amer and Jaipur itself.[38]

Terapanthi

The Terapanthis worship what the idols represent, with ashta-dravya similarly to the Bispanthis, but replace flowers and fruits with dry substitutes. The ashta-dravya jal (water), chandan (sandal), akshata (sacred rice), pushp (yellow rice), deep (yellow dry coconut), dhup (kapoor or cloves) and phal (almonds).[39] Terapanthi is a reformist sect of Digambara Jainism that distinguished itself from the Bispanthi sect. It formed out of strong opposition to the religious domination of traditional religious leaders called bhattarakas in the 17th century. They oppose the worship of various minor gods and goddesses. Some Terapanthi practices, like not using flowers in worship, are followed by most of North Indian Jains. Terapanthis occur in large numbers in Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh.[39]

The Terapanthi movement was born out of the Adhyatma movement that arose in 1626 AD (V.S. 1683) in Agra. Its leading proponent was Banarasidas of Agra.[40]

Bispanthi

Besides tirthankaras, Bispanthi also worship Yaksha and Yakshini like Bhairava and Kshetrapala. Their religious practices include aarti and offerings of flowers, fruits and prasad. Bhattarakas are their dharma-gurus and they are concentrated in Rajasthan, Gujarat, Maharastra and South India. [39]

Differences with Śvētāmbara sect

According to Digambara texts, after attaining Kevala Jnana (omniscience), arihant (omniscient beings) are free from human needs like hunger, thirst, and sleep.[41] In contrast, Śvētāmbara texts preach that it is not so. According to the Digambara tradition, a soul can attain moksha (liberation) only from the male body with complete nudity being a necessity.[42] While, Śvētāmbaras believe that women can attain liberation from female body itself and renunciation of clothes is not at all necessary.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Possehl 2002, p. 111.

- 1 2 3 Zimmer 1953, p. 210.

- ↑ Upinder Singh 2016, p. 444.

- ↑ Umakant Premanand Shah 1987, p. 4.

- ↑ Vijay K. Jain 2012, p. xi-xii.

- 1 2 Pereira 1977, p. 5.

- 1 2 Vijay K. Jain 2012, p. xii.

- ↑ Cort 2010, p. 335.

- 1 2 Dundas 2002, p. 79.

- ↑ Jaini 1991, p. 31.

- ↑ Upinder Singh 2009, p. 524.

- ↑ Satkhandagama : Dhaval (Jivasthana) Satparupana-I (Enunciation of Existence-I) An English Translation of Part 1 of the Dhavala Commentary on the Satkhandagama of Acarya Pushpadanta & Bhutabali Dhavala commentary by Acarya Virasena English tr. by Prof. Nandlal Jain, Ed. by Prof. Ashok Jain ISBN 978-81-86957-47-9

- ↑ Dundas 2002, p. 45.

- ↑ Pramansagar 2008, p. 189–191.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Vijay K. Jain 2013, pp. 189–191, 196–197.

- ↑ Vijay K. Jain 2011, p. 93–100.

- ↑ Champat Rai Jain 1926, p. 26.

- ↑ Vijay K. Jain 2012, p. 144–145.

- ↑ Champat Rai Jain 1926, p. 32–38.

- ↑ Vijay K. Jain 2012, p. 143.

- ↑ Champat Rai Jain 1926, p. 46–47.

- ↑ Upinder Singh 2009, p. 316.

- ↑ Champat Rai Jain 1926, p. 36.

- ↑ Champat Rai Jain 1926, p. 21.

- ↑ Champat Rai Jain 1926, p. 141.

- ↑ Harvey 2014, p. 182.

- ↑ Zimmer 1953, p. 209–210.

- ↑ Zimmer 1953, p. 213.

- ↑ Upinder Singh 2009, p. 444.

- ↑ Dundas 2002, pp. 63–64.

- 1 2 Dundas 2002, p. 80.

- ↑ Jaini 2000, p. 28.

- ↑ Glasenapp, Helmuth (1999). Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 382. ISBN 9788120813762. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ↑ Carrithers & Humphrey 1991, p. 170.

- ↑ Sangave 1980, pp. 51-56.

- ↑ Long 2008, p. 39.

- ↑ Sangave 1980, p. 299.

- ↑ John E. Cort "A Tale of Two Cities: On the Origins of Digambara Sectarianism in North India." L. A. Babb, V. Joshi, and M. W. Meister (eds.), Multiple Histories: Culture and Society in the Study of Rajasthan, 39-83. Jaipur: Rawat, 2002.

- 1 2 3 Sangave 1980, p. 52.

- ↑ Ardhakathanaka: Half a tale, a Study in the Interrelationship between Autobiography and History, Mukunda Lath (trans. and ed.), Jaipur 2005. ISBN 978-8129105660

- ↑ Upinder Singh 2009, p. 314.

- ↑ Upinder Singh 2009, p. 319.

Sources

- Carrithers, Michael; Humphrey, Caroline, eds. (1991), The Assembly of Listeners: Jains in Society, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-365-05-8

- Jain, Vijay K. (2013), Ācārya Nemichandra's Dravyasaṃgraha, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 978-81-903639-5-2,

- Jain, Vijay K. (2012), Acharya Amritchandra's Purushartha Siddhyupaya, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 81-903639-4-8,

- Jain, Vijay K. (2011), Acharya Umasvami's Tattvārthsūtra (1st ed.), (Uttarakhand) India: Vikalp Printers, ISBN 81-903639-2-1,

- Possehl, Gregory L. (2002), The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective, Rowman Altamira, ISBN 978-0-7591-0172-2

- Pramansagar, Muni (2008), Jain Tattva-Vidya, India: Bhartiya Gyanpeeth, ISBN 978-81-263-1480-5

- Singh, Upinder (2009), A History Of Ancient And Early Medieval India: From The Stone Age To The 12Th Century, Pearson Education, ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0

- Singh, Upinder (2016), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Pearson Education, ISBN 978-93-325-6996-6

- Jones, Constance; Ryan, James D. (2006), Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5

- Dundas, Paul (2002) [1992], The Jains (Second ed.), Routledge, ISBN 0-415-26605-X

- Jaini, Padmanabh S. (1991), Gender and Salvation: Jaina Debates on the Spiritual Liberation of Women, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-06820-3

- Jaini, Padmanabh S. (2000), Collected Papers On Jaina Studies (First ed.), Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1691-9

- Pereira, José (1977), Monolithic Jinas, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 0-8426-1027-8

- Mookerji, Radha Kumud (1988) [first published in 1966], Chandragupta Maurya and his times (4th ed.), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0433-3

- Sangave, Vilas Adinath (1980) [1959], Jaina Community: A Social Survey, Popular Prakashan, ISBN 0-317-12346-7

- Shah, Umakant Premanand (1987), Jaina-rūpa-maṇḍana: Jaina iconography, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 81-7017-208-X

- Cort, John (2010) [1953], Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-538502-1

- Zimmer, Heinrich (1953) [April 1952], Campbell, Joseph, ed., Philosophies Of India, London, E.C. 4: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, ISBN 978-81-208-0739-6,

- Jain, Champat Rai (1926), Sannyasa Dharma

External links

- International Digamber Jain Organization