Yahweh

| Deities of the ancient Near East |

|---|

| Religions of the ancient Near East |

Yahweh[Notes 1] was the national god of the Iron Age kingdoms of Israel (Samaria) and Judah.[3] His exact origins are disputed, although they reach back to the early Iron Age and even the Late Bronze:[4][5] his name may have begun as an epithet of El, head of the Bronze Age Canaanite pantheon,[6] but the earliest plausible mentions of Yahweh are in Egyptian texts that refer to a similar-sounding place name associated with the Shasu nomads of the southern Transjordan.[7]

In the oldest biblical literature, Yahweh is a typical ancient Near Eastern "divine warrior", who leads the heavenly army against Israel's enemies;[8] he later became the main god of the Kingdom of Israel (Samaria) and of Judah,[9] and over time the royal court and temple promoted Yahweh as the god of the entire cosmos, possessing all the positive qualities previously attributed to the other gods and goddesses.[10][11] By the end of the Babylonian exile (6th century BCE), the very existence of foreign gods was denied, and Yahweh was proclaimed as the creator of the cosmos and the true god of all the world.[11]

Bronze Age origins

There is almost no agreement on the origins and meaning of Yahweh's name;[12] it is not attested other than among the Israelites, and seems not to have any reasonable etymology (Ehyeh ašer ehyeh, or "I Am that I Am", the explanation presented in Exodus 3:14, appears to be a late theological gloss invented to explain Yahweh's name at a time when the meaning had been lost).[13][14]

The Israelites were originally Canaanites, but Yahweh does not appear to have been a Canaanite god.[15][16][Notes 2] The head of the Canaanite pantheon was El, and one theory holds that the word Yahweh is based on the Hebrew root HYH/HWH, meaning "cause to exist," as a shortened form of the phrase ˀel ḏū yahwī ṣabaˀôt, (Phoenician: 𐤀𐤋 𐤃 𐤉𐤄𐤅𐤄 𐤑𐤁𐤀𐤕) "El who creates the hosts", meaning the heavenly host accompanying El as he marched beside the earthly armies of Israel.[17][12] The argument has numerous weaknesses, including, among others, the dissimilar characters of the two gods, and the fact that el dū yahwī ṣaba’ôt is nowhere attested either inside or outside the Bible.[18][Notes 3]

The oldest plausible recorded occurrence of Yahweh is as a place-name, "land of Shasu of yhw", in an Egyptian inscription from the time of Amenhotep III (1402–1363 BCE),[19][20] the Shasu being nomads from Midian and Edom in northern Arabia.[21] In this case a plausible etymology for the name could be from the root HWY, which would yield the meaning "he blows", appropriate to a weather divinity.[22][23] There is considerable but not universal support for this view,[24] but it raises the question of how he made his way to the north.[25] The widely accepted Kenite hypothesis holds that traders brought Yahweh to Israel along the caravan routes between Egypt and Canaan.[26] The strength of the Kenite hypothesis is that it ties together various points of data, such as the absence of Yahweh from Canaan, his links with Edom and Midian in the biblical stories, and the Kenite or Midianite ties of Moses.[25] However, while it is entirely plausible that the Kenites and others may have introduced Yahweh to Israel, it is unlikely that they did so outside the borders of Israel or under the aegis of Moses, as the Exodus story has it.[27][28]

Iron Age I (1200–930 BCE): El, Yahweh, and the origins of Israel

Israel emerges into the historical record in the last decades of the 13th century BCE, at the very end of the Late Bronze Age when the Canaanite city-state system was ending.[29] The milieu from which Israelite religion emerged was accordingly Canaanite.[30] El, "the kind, the compassionate," "the creator of creatures," was the chief of the Canaanite gods,[31] and he, not Yahweh, was the original "God of Israel"—the word "Israel" is based on the name El rather than Yahweh.[32] He lived in a tent on a mountain from whose base originated all the fresh waters of the world, with the goddess Asherah as his consort.[31][33] This pair made up the top tier of the Canaanite pantheon;[31] the second tier was made up of their children, the "seventy sons of Athirat" (a variant of the name Asherah).[34] Prominent in this group was Baal, who had his home on Mount Zaphon; over time Baal became the dominant Canaanite deity, so that El became the executive power and Baal the military power in the cosmos.[35] Baal's sphere was the thunderstorm with its life-giving rains, so that he was also a fertility god, although not quite the fertility god.[36] Below the seventy second-tier gods was a third tier made up of comparatively minor craftsman and trader deities, with a fourth and final tier of divine messengers and the like.[34] El and his sons made up the Assembly of the Gods, each member of which had a human nation under his care, and a textual variant of Deuteronomy 32:8–9 describes El dividing the nations of the world among his sons, with Yahweh receiving Israel:[32]

When the Most High (’elyôn) gave to the nations their inheritance,

when he separated humanity,

he fixed the boundaries of the peoples

according to the number of divine beings.

For Yahweh's portion is his people,

Jacob his allotted heritage.[Notes 4]

The Israelites initially worshipped Yahweh alongside a variety of Canaanite gods and goddesses, including El, Asherah and Baal.[37] In the period of the Judges and the first half of the monarchy, El and Yahweh became conflated in a process of religious syncretism.[38] As a result, ’el (Hebrew: אל) became a generic term meaning "god", as opposed to the name of a worshipped deity, and epithets such as El Shaddai came to be applied to Yahweh alone, diminishing the worship of El and strengthening the position of Yahweh.[39] Features of Baal, El and Asherah were absorbed into the Yahweh religion, Asherah possibly becoming embodied in the feminine aspects of the Shekinah or divine presence, and Baal's nature as a storm and weather god becoming assimilated into Yahweh's own identification with the storm.[40] In the next stage the Yahweh religion separated itself from its Canaanite heritage, first by rejecting Baal-worship in the 9th century, then through the 8th to 6th centuries with prophetic condemnation of Baal, the asherim, sun-worship, worship on the "high places", practices pertaining to the dead, and other matters.[41]

In the earliest literature such as the Song of the Sea (Exodus 15:1–18, celebrating Yahweh's victory over Egypt at the exodus), Yahweh is a warrior for his people, a storm-god typical of ancient Near Eastern myths, marching out from a region to the south or south-east of Israel with the heavenly host of stars and planets that make up his army.[42] Israel's battles are Yahweh's battles, Israel's victories are his victories, and while other peoples have other gods, Israel's god is Yahweh, who will procure a fertile resting-place for them:[43]

There is none like God, O Jeshurun (i.e., Israel)

who rides through the heavens to your help ...

he subdues the ancient gods, shatters the forces of old ...

so Israel lives in safety, untroubled is Jacob's abode ...

Your enemies shall come fawning to you,

and you shall tread on their backs. (Deuteronomy 33:26–29)

Iron Age II (1000–586 BCE): Yahweh as God of Israel

Iron Age Yahweh was the national god of the kingdoms of Israel and Judah,[3] and appears to have been worshipped only in these two kingdoms;[44] this was unusual in the Ancient Near East but not unknown—the god Ashur, for example, was worshipped only by the Assyrians.[45]

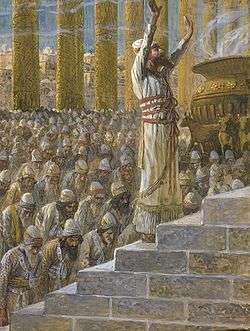

After the 9th century BCE the tribes and chiefdoms of Iron Age I were replaced by ethnic nation states, Israel, Judah, Moab, Ammon and others, each with its national god, and all more or less equal.[46][47] Thus Chemosh was the god of the Moabites, Milcom the god of the Ammonites, Qaus the god of the Edomites, and Yahweh the "God of Israel" (no "God of Judah" is mentioned anywhere in the Bible).[48][49] In each kingdom the king was also the head of the national religion and thus the viceroy on Earth of the national god;[50] in Jerusalem this was reflected each year when the king presided over a ceremony at which Yahweh was enthroned in the Temple.[51]

The centre of Yahweh's worship lay in three great annual festivals coinciding with major events in rural life: Passover with the birthing of lambs, Shavuot with the cereal harvest, and Sukkot with the fruit harvest.[52] These probably pre-dated the arrival of the Yahweh religion,[52] but they became linked to events in the national mythos of Israel: Passover with the exodus from Egypt, Shavuot with the law-giving at Sinai, and Sukkot with the wilderness wanderings.[49] The festivals thus celebrated Yahweh's salvation of Israel and Israel's status as his holy people, although the earlier agricultural meaning was not entirely lost.[53] His worship presumably involved sacrifice, but many scholars have concluded that the rituals detailed in Leviticus 1–16, with their stress on purity and atonement, were introduced only after the Babylonian exile, and that in reality any head of a family was able to offer sacrifice as occasion demanded.[54] (A number of scholars have also drawn the conclusion that infant sacrifice, whether to the underworld deity Molech or to Yahweh himself, was a part of Israelite/Judahite religion until the reforms of King Josiah in the late 7th century BCE).[55] Sacrifice was presumably complemented by the singing or recital of psalms, but again the details are scant.[56] Prayer played little role in official worship.[57]

The Hebrew Bible gives the impression that the Jerusalem temple was always meant to be the central or even sole temple of Yahweh, but this was not the case:[49] the earliest known Israelite place of worship is a 12th-century open-air altar in the hills of Samaria featuring a bronze bull reminiscent of Canaanite "Bull-El" (El in the form of a bull), and the archaeological remains of further temples have been found at Dan on Israel's northern border and at Arad in the Negev and Beersheba, both in the territory of Judah.[58] Shiloh, Bethel, Gilgal, Mizpah, Ramah and Dan were also major sites for festivals, sacrifices, the making of vows, private rituals, and the adjudication of legal disputes.[59]

Yahweh-worship was famously aniconic, meaning that the god was not depicted by a statue or other image. This is not to say that he was not represented in some symbolic form, and early Israelite worship probably focused on standing stones, but according to the Biblical texts the temple in Jerusalem featured Yahweh's throne in the form of two cherubim, their inner wings forming the seat and a box (the Ark of the Covenant) as a footstool, while the throne itself was empty.[60] No satisfactory explanation of Israelite aniconism has been advanced, and a number of recent scholars have argued that Yahweh was in fact represented prior to the reforms of Hezekiah and Josiah late in the monarchic period: to quote one recent study, "[a]n early aniconism, de facto or otherwise, is purely a projection of the post-exilic imagination" (MacDonald, 2007).[61]

Yahweh and the rise of monotheism

Pre-exilic Israel, like its neighbours, was polytheistic,[64] and Israelite monotheism was the result of unique historical circumstances.[65] The original god of Israel was El, as the name demonstrates—its probable meaning is "may El rule" or some other sentence-form involving the name of El.[66] In the early tribal period, each tribe would have had its own patron god; when kingship emerged, the state promoted Yahweh as the national god of Israel, supreme over the other gods, and gradually Yahweh absorbed all the positive traits of the other gods and goddesses.[11] Yahweh and El merged at religious centres such as Shechem, Shiloh and Jerusalem,[67] with El's name becoming a generic term for "god" and Yahweh, the national god, appropriating many of the older supreme god's titles such as El Shaddai (Almighty) and Elyon (Most High).[68]

Asherah, formerly the wife of El, was worshipped as Yahweh's consort[69] or mother;[70] potsherds discovered at Khirbet el-Kôm and Kuntillet Ajrûd make reference to "Yahweh and his Asherah",[71][72] and various biblical passages indicate that her statues were kept in his temples in Jerusalem, Bethel, and Samaria.[73][74] Yahweh may also have appropriated Anat, the wife of Baal, as his consort, as Anat-Yahu ("Anat of Yahu," i.e., Yahweh) is mentioned in 5th century BCE records from the Jewish colony at Elephantine in Egypt.[75] A goddess called the Queen of Heaven was also worshipped, probably a fusion of Astarte and the Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar,[73] possibly a title of Asherah.[76] Worship of Baal and Yahweh coexisted in the early period of Israel's history, but they were considered irreconcilable after the 9th century BCE, following the efforts of King Ahab and his queen Jezebel to elevate Baal to the status of national god,[77] although the cult of Baal did continue for some time.[78]

The worship of Yahweh alone began at the earliest with Elijah in the 9th century BCE, but more likely with the prophet Hosea in the 8th; even then it remained the concern of a small party before gaining ascendancy in the exilic and early post-exilic period.[64] The early supporters of this faction are widely regarded as being monolatrists rather than true monotheists;[79] they did not believe that Yahweh was the only god in existence, but instead believed that he was the only god the people of Israel should worship.[80] Finally, in the national crisis of the exile, the followers of Yahweh went a step further and outright denied that the other deities aside from Yahweh even existed, thus marking the transition from monolatrism to true monotheism.[11]

Second Temple Judaism

In 539 BCE Babylon itself fell to the Persian conqueror Cyrus, and in 538 BCE the exiles were permitted to return to Yehud medinata, as the Persian province of Judah was known.[81] The Temple is commonly said to have been rebuilt in the period 520–515 BCE, but it seems probable that this is an artificial date chosen so that 70 years could be said to have passed between the destruction and the rebuilding, fulfilling a prophecy of Jeremiah.[82][81][83]

In recent decades, it has become increasingly common among scholars to assume that much of the Hebrew bible was assembled, revised and edited in the 5th century BCE to reflect the realities and challenges of the Persian era.[84][85] The returnees had a particular interest in the history of Israel: the written Torah (the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy), for example, may have existed in various forms during the Monarchy (the period of the kingdoms of Israel and Judah), but it was in the Second Temple that it was edited and revised into something like its current form, and the Chronicles, a new history written at this time, reflects the concerns of the Persian Yehud in its almost-exclusive focus on Judah and the Temple.[84]

Prophetic works were also of particular interest to the Persian-era authors, with some works being composed at this time (the last ten chapters of Isaiah and the books of Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi and perhaps Joel) and the older prophets edited and reinterpreted. The corpus of Wisdom books saw the composition of Job, parts of Proverbs, and possibly Ecclesiastes, while the book of Psalms was possibly given its modern shape and division into five parts at this time (although the collection continued to be revised and expanded well into Hellenistic and even Roman times).[84]

Second Temple Judaism was centered not on synagogues, which began to appear only in the 3rd century BCE, and the reading and study of scripture, but on the Temple itself, and on a cycle of continual blood sacrifice (meaning the sacrifice of live animals). Torah, or ritual law, was also important, and the Temple priests were responsible for teaching it, but the concept of scripture developed only slowly. While the written Torah (the Pentateuch) and the Prophets were accepted as authoritative by the 1st century CE, beyond this core the different Jewish groups continued to accept different groups of books as authoritative.[86]

During the Second Temple period, speaking the name of Yahweh in public became regarded as taboo.[87] When reading from the scriptures, Jews began to substitute the divine name with the word adonai (אֲדֹנָי), meaning "Lord".[88] The High Priest was permitted to speak the name once in the Temple during the Day of Atonement, but at no other time and in no other place.[88] During the Hellenistic period, the scriptures were translated into Greek by the Jews of the Egyptian diaspora.[89] Greek translations of the Hebrew scriptures render both the tetragrammaton and adonai as kyrios (κύριος), meaning "the Lord".[88] After the Temple was destroyed in 70 CE, the original pronunciation of the tetragrammaton was forgotten.[88]

The period of Persian rule saw the development of expectation in a future human king who would rule purified Israel as Yahweh's representative at the end of time–that is, a messiah. The first to mention this were Haggai and Zechariah, both prophets of the early Persian period. They saw the messiah in Zerubbabel, a descendant of the House of David who seemed, briefly, to be about to re-establish the ancient royal line, or in Zerubbabel and the first High Priest, Joshua (Zechariah writes of two messiahs, one royal and the other priestly). These early hopes were dashed (Zerubabbel disappeared from the historical record, although the High Priests continued to be descended from Joshua), and thereafter there are merely general references to a Messiah of (meaning descended from) David.[90][91] From these ideas, Christianity, Rabbinic Judaism, and Islam would later emerge.

Graeco-Roman syncretism

Yahweh is frequently invoked in Graeco-Roman magical texts dating from the second century BCE to the fifth century CE, most notably in the Greek Magical Papyri,[92] under the names Iao, Adonai, Sabaoth, and Eloai.[93] In these texts, he is often mentioned alongside traditional Graeco-Roman deities and also Egyptian deities.[93] The archangels Michael, Gabriel, Raphael, and Ouriel and Jewish cultural heroes such as Abraham, Jacob, and Moses are also invoked frequently as well.[94] The frequent occurrence of Yahweh's name is probably due to Greek and Roman folk magicians seeking to make their spells more powerful through the invocation of a prestigious foreign deity.[95]

Tacitus, John the Lydian, and Cornelius Labeo all identify Yahweh with the Greek god Dionysus.[96] Jews themselves frequently used symbols that were also associated with Dionysus such as kylixes, amphorae, leaves of ivy, and clusters of grapes.[97] In his Quaestiones Convivales, the Greek writer Plutarch of Chaeronea writes that the Jews hail their god with cries of "Euoi" and "Sabi", phrases associated with the worship of Dionysus.[98][99][100] According to Sean M. McDonough, Greek-speakers may have confused Aramaic words such as Sabbath, Alleluia, or even possibly some variant of the name Yahweh itself for more familiar terms associated with Dionysus.[101]

See also

- Ancient Semitic religion

- Enlil

- God in Abrahamic religions

- Historicity of the Bible

- History of ancient Israel and Judah

- Jah, a short form of the name

- Jehovah

- Marduk, national god of Babylon

- Names of God in Judaism

- Qos, national god of Edom

- Sacred Name Movement

- Tutelary deity

Notes

- ↑ /ˈjɑːhweɪ/, or often /ˈjɑːweɪ/ in English; Hebrew: יַהְוֶה [jahˈwe], 𐤉𐤄𐤅𐤄 in Paleo-Hebrew

- ↑ "Canaanites" in this article means the indigenous Bronze Age and early Iron Age inhabitants of southern Syria, the coast of Lebanon, Israel, the West Bank and Jordan – see Dever, 2002, p. 219

- ↑ For the full list of reasons, see Day, 2002, p. 13-14

- ↑ For the varying texts of this verse, see Smith, 2010, pp.139–140 and also chapter 4.

References

Citations

- ↑ Van Der Toorn 1999, p. 766.

- ↑ Edelman 1995, p. 190.

- 1 2 Miller 1986, p. 110.

- ↑ Smith 2010, p. 96-98.

- ↑ Miller 2000, p. 1.

- ↑ Dijkstra 2001, p. 92.

- ↑ Dever 2003b, p. 128.

- ↑ Hackett 2001, pp. 158–59.

- ↑ Smith 2002, p. 72.

- ↑ Wyatt 2010, pp. 69–70.

- 1 2 3 4 Betz 2000, p. 917.

- 1 2 Kaiser 2017, p. unpaginated.

- ↑ Hoffman 2004, p. 326.

- ↑ Parke-Taylor 1975, p. 51"The view adopted by this study is as follows. The ehyeh aser ehyeh clause in Exodus 3:14 is a relatively late attempt to explain the divine name by appeal to the root hayah the verb "to be.""

- ↑ Day 2002, p. 15.

- ↑ Dever 2003b, p. 125.

- ↑ Miller 2000, p. 2.

- ↑ Day 2002, p. 13-14.

- ↑ Freedman, O'Connor & Ringgren 1986, p. 520.

- ↑ Anderson 2015, p. 510.

- ↑ Grabbe 2007, p. 151.

- ↑ Dicou 1994, pp. 167–81, 177.

- ↑ Anderson 2015, p. 101.

- ↑ Grabbe 2007, p. 153.

- 1 2 Van der Toorn 1999, p. 912.

- ↑ Van der Toorn 1999, pp. 912–13.

- ↑ Van der Toorn 1999, pp. 912–913.

- ↑ Van der Toorn 1995, pp. 247–48.

- ↑ Noll 2001, p. 124–126.

- ↑ Cook 2004, p. 7.

- 1 2 3 Coogan & Smith 2012, p. 8.

- 1 2 Smith 2002, p. 32.

- ↑ Smith 2002, p. 33.

- 1 2 Hess 2007, p. 103.

- ↑ Coogan & Smith 2012, p. 7–8.

- ↑ Handy 1994, p. 101.

- ↑ Smith 2002, p. 7.

- ↑ Smith 2002, p. 8.

- ↑ Smith 2002, p. 33-34.

- ↑ Smith 2002, p. 8,135.

- ↑ Smith 2002, p. 9.

- ↑ Hackett 2001, p. 158–159.

- ↑ Hackett 2001, p. 160.

- ↑ Grabbe 2010, p. 184.

- ↑ Noll 2001, p. 251.

- ↑ Schniedewind 2013, p. 93.

- ↑ Smith 2010, p. 119.

- ↑ Hackett 2001, p. 156.

- 1 2 3 Davies 2010, p. 112.

- ↑ Miller 2000, p. 90.

- ↑ Petersen 1998, p. 23.

- 1 2 Albertz 1994, p. 89.

- ↑ Gorman 2000, p. 458.

- ↑ Davies & Rogerson 2005, pp. 151–52.

- ↑ Gnuse 1997, p. 118.

- ↑ Davies & Rogerson 2005, pp. 158–65.

- ↑ Cohen 1999, p. 302.

- ↑ Dever 2003a, p. 388.

- ↑ Bennett 2002, p. 83.

- ↑ Mettinger 2006, pp. 288–90.

- ↑ MacDonald 2007, pp. 21, 26–27.

- ↑ Vriezen & van der Woude 2005, p. 18.

- 1 2 3 4 Hess 2012, p. 472.

- 1 2 Albertz 1994, p. 61.

- ↑ Gnuse 1997, p. 214.

- ↑ Romer 2014, p. unpaginated.

- ↑ Smith 2001, p. 140.

- ↑ Smith 2002, pp. 33, 47.

- ↑ Niehr 1995, pp. 54, 57.

- ↑ Barker 2012, pp. 80–86.

- ↑ Vriezen & van der Woude 2005, pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Barker 2012, p. 32.

- 1 2 Ackerman 2003, p. 395.

- ↑ Barker 2012, pp. 154–157.

- ↑ Day 2002, p. 143.

- ↑ Barker 2012, p. 41.

- ↑ Smith 2002, p. 47.

- ↑ Smith 2002, p. 74.

- ↑ Eakin 1971, pp. 70 and 263.

- ↑ McKenzie 1990, p. 1287.

- 1 2 Coogan, Brettler & Newsom 2007, p. xxii.

- ↑ Grabbe 2010, p. 2–3.

- ↑ Davies & Rogerson 2005, p. 89.

- 1 2 3 Coogan, Brettler & Newsom 2007, p. xxiii.

- ↑ Berquist 2007, p. 3–4.

- ↑ Grabbe 2010, p. 40–42.

- ↑ Leech 2002, pp. 59–60.

- 1 2 3 4 Leech 2002, p. 60.

- ↑ Coogan, Brettler & Newsom 2007, p. xxvi.

- ↑ Wanke 1984, p. 182-183.

- ↑ Albertz 2003, p. 130.

- ↑ Betz 1996.

- 1 2 Smith & Cohen 1996b, pp. 242–56.

- ↑ Arnold 1996.

- ↑ Smith & Cohen 1996b, pp. 242–256.

- ↑ McDonough 1999, p. 88.

- ↑ Smith & Cohen 1996a, p. 233.

- ↑ Plutarch, Quaestiones Convivales, Question VI

- ↑ McDonough 1999, p. 89.

- ↑ Smith & Cohen 1996a, pp. 232–233.

- ↑ McDonough 1999, pp. 89–90.

Bibliography

- Ackerman, Susan (2003). "Goddesses". In Richard, Suzanne. Near Eastern Archaeology:A Reader. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-083-5.

- Ahlström, Gösta Werner (1991). "The Role of Archaeological and Literary Remains in Reconstructing Israel's History". In Edelman, Diana Vikander. The Fabric of History: Text, Artifact and Israel's Past. A&C Black. ISBN 9780567491107.

- Ahlström, Gösta Werner (1993). The History of Ancient Palestine. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8006-2770-6.

- Albertz, Rainer (1994). A History of Israelite Religion, Volume I: From the Beginnings to the End of the Monarchy. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 9780664227197.

- Allen, Spencer L. (2015). The Splintered Divine: A Study of Istar, Baal, and Yahweh Divine Names and Divine Multiplicity in the Ancient Near East. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9781501500220.

- Anderson, James S. (2015). Monotheism and Yahweh's Appropriation of Baal. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9780567663962.

- Barker, Margaret (1992). The Great Angel: A Study of Israel's Second God. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664253950.

- Barker, Margaret (2012), The Lady in the Temple, The Mother of the Lord, 1, London, England: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, ISBN 978-0567362469

- Becking, Bob (2001). "The Gods in Whom They Trusted". In Becking, Bob. Only One God?: Monotheism in Ancient Israel and the Veneration of the Goddess Asherah. A&C Black. ISBN 9780567232120.

- Bennett, Harold V. (2002). Injustice Made Legal: Deuteronomic Law and the Plight of Widows, Strangers, and Orphans in Ancient Israel. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802839091.

- Berquist, Jon L. (2007). Approaching Yehud: New Approaches to the Study of the Persian Period. SBL Press. ISBN 9781589831452.

- Betz, Arnold Gottfried (2000). "Monotheism". In Freedman, David Noel; Myer, Allen C. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-9053565032.

- Betz, Hans Dieter (1996). The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation Including the Demonic Spells (2 ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226044477.

- Chalmers, Aaron (2012). Exploring the Religion of Ancient Israel: Prophet, Priest, Sage and People. SPCK. ISBN 9780281069002.

- Arnold, Clinton E. (1996). The Colossian Syncretism: The Interface Between Christianity and Folk Belief at Colossae. Eugene, Oregon: Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-1-4982-1757-6.

- Cohen, Shaye J.D. (1999). "The Temple and the Synagogue". In Finkelstein, Louis; Davies, W. D.; Horbury, William. The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 3, The Early Roman Period. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521243773.

- Cohn, Norman (2001). Cosmos, Chaos, and the World to Come: The Ancient Roots of Apocalyptic Faith. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300090888.

- Collins, John J. (2005). The Bible After Babel: Historical Criticism in a Postmodern Age. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802828927.

- Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann (2007). "Editors' Introduction". In Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195288803.

- Coogan, Michael D.; Smith, Mark S. (2012). Stories from Ancient Canaan (2nd Edition). Presbyterian Publishing Corp. ISBN 978-9053565032.

- Cook, Stephen L. (2004). The Social Roots of Biblical Yahwism. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 9781589830981.

- Darby, Erin (2014). Interpreting Judean Pillar Figurines: Gender and Empire in Judean Apotropaic Ritual. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161524929.

- Davies, Philip R.; Rogerson, John (2005). The Old Testament World. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 9780567084880.

- Davies, Philip R. (2010). "Urban Religion and Rural Religion". In Stavrakopoulou, Francesca; Barton, John. Religious Diversity in Ancient Israel and Judah. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 9780567032164.

- Day, John (2002). Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan. Continuum. ISBN 9780567537836.

- Dever, William G. (2003a). "Religion and Cult in the Levant". In Richard, Suzanne. Near Eastern Archaeology:A Reader. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-083-5.

- Dever, William G. (2003b). Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802844163.

- Dever, William G. (2005). Did God Have A Wife?: Archaeology And Folk Religion In Ancient Israel. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2852-1.

- Dicou, Bert (1994). Edom, Israel's Brother and Antagonist: The Role of Edom in Biblical Prophecy and Story. A&C Black. ISBN 9781850754589.

- Dijkstra, Meindert (2001). "El the God of Israel-Israel the People of YHWH: On the Origins of Ancient Israelite Yahwism". In Becking, Bob; Dijkstra, Meindert; Korpel, Marjo C.A.; et al. Only One God?: Monotheism in Ancient Israel and the Veneration of the Goddess Asherah. A&C Black. ISBN 9781841271996.

- Eakin, Frank E. Jr. The Religion and Culture of Israel (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1971), 70 and 263.

- Edelman, Diana V. (1995). "Tracking Observance of the Aniconic Tradition". In Edelman, Diana Vikander. The Triumph of Elohim: From Yahwisms to Judaisms. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-9053565032.

- Elior, Rachel (2006). "Early Forms of Jewish Mysticism". In Katz, Steven T. The Cambridge History of Judaism: The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521772488.

- Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2002). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Sacred Texts. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780743223386.

- Freedman, D.N.; O'Connor, M.P.; Ringgren, H. (1986). "YHWH". In Botterweck, G.J.; Ringgren, H. Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament. 5. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802823298.

- Frerichs, Ernest S. (1998). The Bible and Bibles in America. Scholars Press. ISBN 9781555400965.

- Gnuse, Robert Karl (1997). No Other Gods: Emergent Monotheism in Israel. Continuum. ISBN 9780567374158.

- Gnuse, Robert (1999). "The Emergence of Monotheism in Ancient Israel: A Survey of Recent Scholarship". Religion. 29 (4): 315–36. doi:10.1006/reli.1999.0198.

- Gorman, Frank H., Jr. (2000). "Feasts, Festivals". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-1-57506-083-5.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2010). An Introduction to Second Temple Judaism. A&C Black. ISBN 9780567552488.

- Grabbe, Lester (2010). "'Many nations will be joined to YHWH in that day': The question of YHWH outside Judah". In Stavrakopoulou, Francesca; Barton, John. Religious diversity in Ancient Israel and Judah. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-567-03216-4.

- Grabbe, Lester (2007). Ancient Israel: What Do We Know and How Do We Know It?. A&C Black. ISBN 9780567032546.

- Hackett, Jo Ann (2001). "'There Was No King In Israel': The Era of the Judges". In Coogan, Michael David. The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513937-2.

- Halpern, Baruch; Adams, Matthew J. (2009). From Gods to God: The Dynamics of Iron Age Cosmologies. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161499029.

- Handy, Lowell K. (1994). Among the Host of Heaven: The Syro-Palestinian Pantheon as Bureaucracy. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9780931464843.

- Hess, Richard S. (2007). Israelite Religions: An Archaeological and Biblical Survey. Baker Academic. ISBN 9780801027178.

- Hess, Richard S. (2012), "Yahweh's "Wife" and Belief in One God in the Old Testament", in Hoffmeier, James K.; Magary, Dennis R., Do Historical Matters Matter to Faith?: A Critical Appraisal of Modern and Postmodern Approaches to Scripture, Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway, pp. 459–476, ISBN 978-1-4335-2574-2

- Hoffman, Joel (2004). In the Beginning: A Short History of the Hebrew Language. NYU Press. ISBN 9780814737064.

- Humphries, W. Lee (1990). "God, Names of". In Mills, Watson E.; Bullard, Roger Aubrey. Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780865543737.

- Kaiser, Walter C., Jr. (2017). Exodus. Zondervan. ISBN 9780310531739.

- Keel, Othmar (1997). The Symbolism of the Biblical World: Ancient Near Eastern Iconography and the Book of Psalms. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575060149.

- Leech, Kenneth (2002) [1985], Experiencing God: Theology as Spirituality, Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock Publishers, ISBN 978-1579106133

- Lemche, Niels Peter (1998). The Israelites in History and Tradition. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664227272.

- Levin, Christoph (2013). Re-Reading the Scriptures: Essays on the Literary History of the Old Testament. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161522079.

- Liverani, Mario (2014). Israel's History and the History of Israel. Routledge. ISBN 978-1317488934.

- Mafico, Temba L.J. (1992). "The Divine Name Yahweh Alohim from an African Perspective". In Segovia, Fernando F.; Tolbert, Mary Ann. Reading from this Place: Social Location and Biblical Interpretation in Global Perspective. 2. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781451407884.

- Mastin, B.A. (2005). "Yahweh's Asherah, Inclusive Monotheism and the Question of Dating". In Day, John. In Search of Pre-Exilic Israel. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9780567245540.

- McDonough, Sean M. (1999), YHWH at Patmos: Rev. 1:4 in Its Hellenistic and Early Jewish Setting, Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 2. Reihe, 107, Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, ISBN 978-3-16-147055-4, ISSN 0340-9570

- McKenzie, John L. "Aspects of Old Testament Thought" in Raymond E. Brown, Joseph A. Fitzmyer, and Roland E. Murphy, eds., The New Jerome Biblical Commentary (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1990), 1287, S.v. 77:17.

- Mettinger, Tryggve N.D. (2006). "A Conversation With My Critics: Cultic Image or Aniconism in the First Temple?". In Amit, Yaira; Naʼaman, Nadav. Essays on Ancient Israel in Its Near Eastern Context. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575061283.

- Meyers, Carol (2001). "Kinship and Kingship: The early Monarchy". In Coogan, Michael David. The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513937-2.

- MacDonald, Nathan (2007). "Aniconism in the Old Testament". In Gordon, R.P. The God of Israel. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521873659.

- Miller, Patrick D (2000). The Religion of Ancient Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22145-4.

- Miller, Patrick D (1986). A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664212629.

- Moore, Megan Bishop; Kelle, Brad E. (2011). Biblical History and Israel's Past: The Changing Study of the Bible and History. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802862600.

- Nestor, Dermot Anthony, Cognitive Perspectives on Israelite Identity, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2010

- Niehr, Herbert (1995). "The Rise of YHWH in Judahite and Israelite Religion". In Edelman, Diana Vikander. The Triumph of Elohim: From Yahwisms to Judaisms. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-9053565032.

- Noll, K.L. (2001). Canaan and Israel in Antiquity: An Introduction. A&C Black. ISBN 9781841272580.

- Parke-Taylor, G. H. (1975), Yahweh: The Divine Name in the Bible, Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, ISBN 978-0-88920-013-5

- Petersen, Allan Rosengren (1998). The Royal God: Enthronement Festivals in Ancient Israel and Ugarit?. A&C Black. ISBN 9781850758648.

- Romer, Thomas (2014). The Invention of Yahweh. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674915756.

- Schniedewind, William M. (2013). A Social History of Hebrew: Its Origins Through the Rabbinic Period. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300176681.

- Smith, Mark S. (2000). "El". In Freedman, David Noel; Myer, Allen C. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Smith, Mark S. (2001). The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel's Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195167689.

- Smith, Mark S. (2002). The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel (2nd ed.). Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802839725.

- Smith, Mark S. (2003). "Astral Religion and the Divinity". In Noegel, Scott; Walker, Joel. Prayer, Magic, and the Stars in the Ancient and Late Antique World. Penn State Press. ISBN 978-0271046006.

- Smith, Mark S. (2010). God in Translation: Deities in Cross-Cultural Discourse in the Biblical World. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802864338.

- Smith, Morton (1984). "Jewish Religious Life in the Persian Period". In Finkelstein, Louis. The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 1, Introduction: The Persian Period. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521218801.

- Smith, Morton; Cohen, Shaye J.D. (1996a). Studies in the Cult of Yahweh: Volume One: Studies in Historical Method, Ancient Israel, Ancient Judaism. Leiden, The Netherlands, New York City, New York, and Cologne, Germany: E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-10477-8.

- Smith, Morton; Cohen, Shaye J.D. (1996b). Studies in the Cult of Yahweh: Volume Two: New Testament, Christianity, and Magic. Leiden, The Netherlands, New York City, New York, and Cologne, Germany: E. J. Brill. pp. 242–56. ISBN 978-90-04-10479-2.

- Sommer, Benjamin D. (2011). "God, names of". In Berlin, Adele; Grossman, Maxine L. The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199730049.

- Van der Toorn, Karel (1995). "Ritual Resistance and Self-Assertion". In Platvoet, Jan. G.; Van der Toorn, Karel. Pluralism and Identity: Studies in Ritual Behaviour. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004103733.

- Van der Toorn, Karel (1999). "Yahweh". In Van der Toorn, Karel; Becking, Bob; Van der Horst, Pieter Willem. Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802824912.

- Van der Toorn, Karel (1996). Family Religion in Babylonia, Ugarit and Israel: Continuity and Changes in the Forms of Religious Life. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004104105.

- Vriezen, T. C.; van der Woude, Simon Adam (2005), Ancient Israelite And Early Jewish Literature, translated by Doyle, Brian, Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-12427-1

- Wright, J. Edward (2002). The Early History of Heaven. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195348491.

- Wyatt, Nicolas (2010). "Royal Religion in Ancient Judah". In Stavrakopoulou, Francesca; Barton, John. Religious Diversity in Ancient Israel and Judah. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-567-03216-4.