Lotus position

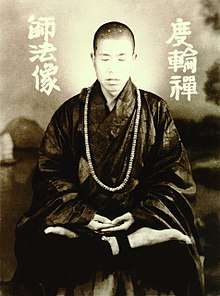

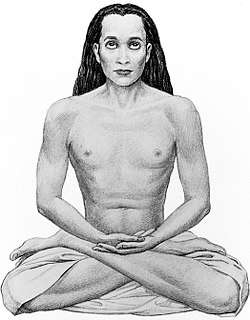

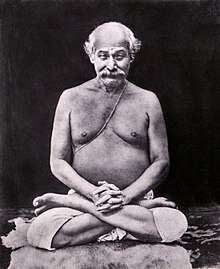

Padmasana or Lotus Position (Sanskrit: पद्मासन [pɐd̪mɑːs̪ɐn̪ɐ], IAST: padmāsana)[1] is a cross-legged sitting asana originating in meditative practices of ancient India, in which the feet are placed on the opposing thighs. It is an established asana, commonly used for meditation, in the Yoga, Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist contemplative traditions. The asana is said to resemble a lotus, to encourage breathing properly through associated meditative practice, and to foster physical stability.

Shiva, the meditating ascetic God of Hinduism, Siddhartha Gautama, the founder of Buddhism, and the Tirthankaras (Ford-Makers) in Jainism have been depicted in the lotus position.

Etymology

Padmāsana means "Lotus throne" and is also a term for actual thrones, often decorated with lotus foliage motifs, on which figures in art sit. The Hindu (Vedic) and Jain Goddess of Prosperity, Sri Lakshmi, sits atop a lotus flower.

In Chinese Buddhism, the lotus position is also called the "vajra position" (Skt. vajrāsana, Ch. 金剛座 jīngāngzuò).[2] The traditions of Tibetan Buddhism also refer to the lotus position as the "vajra position."[3]

Position

From the common sitting down on the floor (Indian Style, Cross-legged) position (asana), one foot is placed on top of the opposite thigh with its sole facing upward and heel close to the abdomen. The other foot is then lifted up slowly and placed on the opposite thigh in a symmetrical way.

The knees are in contact with the ground. The torso is placed in balance and alignment such that the spinal column supports it with minimal muscular effort. The torso is centered above the hips. To relax the head and neck, the jaw is allowed to fall towards the neck and the back of the neck to lengthen. The shoulders move backwards and the ribcage lifts. The tongue rests on the roof of the mouth. The hands may rest on the knees in chin or jnana mudra. The arms are relaxed with the elbows slightly bent.

The eyes may be closed, the body relaxed, with awareness of the overall asana. Adjustments are made until balance and alignment are experienced. Alignment that creates relaxation is indicative of a suitable position for the asana. The asana should be natural and comfortable, without any sharp pains.

In most cases, a cushion (zafu) or mat (zabuton) is necessary in order to achieve this balance. One sits on the forward edge of the cushion or mat in order to incline one's pelvis forward, making it possible to center the spine and provide the necessary support. Only the most flexible people can achieve this asana without a support under their pelvis (and likewise does the Dalai Lama explicitly advise).[4]

Iconography

In Jainism, a Tirthankara is represented either seated in Lotus posture or standing in the Kayotsarga posture.[5]

In Balinese Hinduism, a prominent feature of temples is a special form of padmasana shrine, with empty thrones mounted on a column, for deities, especially Acintya.

Contra-indications

Other meditation asanas are indicated until sufficient flexibility has been developed to sit comfortably in the Lotus. Sciatica, sacral infections and weak or injured knees are contra-indications to attempting the asana.[6]

If the knees point in when your feet point straight ahead, the lotus position may be impossible to achieve. The joints on the opposite ends of the femurs and tibiae are rotated, relative to each other.[7]

See also

References

- ↑ Budilovsky, Joan; Adamson, Eve (2000). The complete idiot's guide to yoga (2 ed.). Penguin. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-02-863970-3. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ↑ Hua, Hsuan (2004). The Chan handbook: talks about meditation (PDF). Buddhist Text Translation Society. p. 34. ISBN 0-88139-951-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 March 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ↑ Patrul Rinpoche. Words of My Perfect Teacher: A Complete Translation of a Classic Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism, rev. ed., trans. Padmakara Translation Group, Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press, 1998, 440.

- ↑ track 1 of "Opening the Eye of New Awareness"

- ↑ Zimmer, Heinrich (1953) [April 1952], Campbell, Joseph, ed., Philosophies Of India, London, E.C. 4: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, p. 209–10, ISBN 978-81-208-0739-6

- ↑ How to sit cross-legged, when hip joint or knees are not flexible , Yogi with Coffee, 1 August 2016

- ↑ "Health Guide to Torsional Deformity". drugs.com. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

Further reading

- Iyengar, B. K. S. (1 October 2005). Illustrated Light On Yoga. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-81-7223-606-9. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- Saraswati, Janakananda (1 February 1992). Yoga, Tantra and Meditation in Daily Life. Weiser Books. ISBN 978-0-87728-768-1. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- Saraswati, Satyananda (1 August 2003). Asana Pranayama Mudra Bandha. Nesma Books India. ISBN 978-81-86336-14-4. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- Saraswati, Satyananda (January 2004). A Systematic Course in the Ancient Tantric Techniques of Yoga and Kriya. Nesma Books India. ISBN 978-81-85787-08-4. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- Temple, Anton (2007). Becoming the lotus: a systematic course of stretching and posture leading to the safe and comfortable adoption of the lotus posture, including a guide to the symbolism and spiritual meaning behind the lotus flower. Merkur. ISBN 978-1-885928-18-4. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

External links

- Padmāsana (पद्मासन) with detail explanation

- Detailed non-commercial article with references, updated 24.06.2006:

- How to sit in Ardha Padmasana

- How to sit in padmasana or sukhasana when not flexible

.jpg)