Gautama Buddha

| Gautama Buddha | |

|---|---|

.jpg) A statue of the Buddha from Sarnath, Uttar Pradesh, India, 4th century CE | |

| Religion | Buddhism |

| Known for | Founder of Buddhism |

| Other names | Siddhartha Gautama, Siddhattha Gotama, Shakyamuni |

| Personal | |

| Born |

c. 563 or c. 480 BCE[1][2] Lumbini, Shakya Republic (according to Buddhist tradition)[note 1] |

| Died |

c. 483 or c. 400 BCE (aged 80) Kushinagar, Malla Republic (according to Buddhist tradition)[note 2] |

| Spouse | Yasodharā |

| Children | |

| Parents |

|

| Senior posting | |

| Predecessor | Kassapa Buddha |

| Successor | Maitreya |

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

Gautama Buddha[note 3] (c. 563/480 – c. 483/400 BCE), also known as Siddhārtha Gautama,[note 4] Shakyamuni (i.e. "Sage of the Shakyas") Buddha,[4][note 5] or simply the Buddha, after the title of Buddha, was a monk (śramaṇa)[5][6], mendicant, and sage,[4] on whose teachings Buddhism was founded.[7] He is believed to have lived and taught mostly in the northeastern part of ancient India sometime between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE.[8][note 6]

Gautama taught a Middle Way between sensual indulgence and the severe asceticism found in the śramaṇa movement[9] common in his region. He later taught throughout other regions of eastern India such as Magadha and Kosala.[8][10]

Gautama is the primary figure in Buddhism. He is believed by Buddhists to be an enlightened teacher who attained full Buddhahood and shared his insights to help sentient beings end rebirth and suffering. Accounts of his life, discourses and monastic rules are believed by Buddhists to have been summarised after his death and memorized by his followers. Various collections of teachings attributed to him were passed down by oral tradition and first committed to writing about 400 years later.

In Vaishnava Hinduism, the historic Buddha is considered to be an avatar of the Hindu god Vishnu.[11] Of the ten major avatars of Vishnu, Vaishnavites believe Gautama Buddha to be the ninth and most recent incarnation.[12][13]

Historical Siddhārtha Gautama

Scholars are hesitant to make unqualified claims about the historical facts of the Buddha's life. Most people accept that the Buddha lived, taught, and founded a monastic order during the Mahajanapada era during the reign of Bimbisara (c. 558 – c. 491 BCE, or c. 400 BCE),[14][15][16] the ruler of the Magadha empire, and died during the early years of the reign of Ajatasatru, who was the successor of Bimbisara, thus making him a younger contemporary of Mahavira, the Jain tirthankara.[17][18] While the general sequence of "birth, maturity, renunciation, search, awakening and liberation, teaching, death" is widely accepted,[19] there is less consensus on the veracity of many details contained in traditional biographies.[20][21]

The times of Gautama's birth and death are uncertain. Most historians in the early 20th century dated his lifetime as c. 563 BCE to 483 BCE.[1][22] More recently his death is dated later, between 411 and 400 BCE, while at a symposium on this question held in 1988,[23][24][25] the majority of those who presented definite opinions gave dates within 20 years either side of 400 BCE for the Buddha's death.[1][26][note 6] These alternative chronologies, however, have not been accepted by all historians.[31][32][note 7]

Historical context

.png)

The evidence of the early texts suggests that Siddhārtha Gautama was born into the Shakya clan, a community that was on the periphery, both geographically and culturally, of the eastern Indian subcontinent in the 5th century BCE.[37] One of his usual names was "Sakamuni" or "Sakyamunī" ("Sage of the Shakyas"). It was either a small republic, or an oligarchy, and his father was an elected chieftain, or oligarch.[37] According to the Buddhist tradition, Gautama was born in Lumbini, now in modern-day Nepal, and raised in the Shakya capital of Kapilvastu, which may have been either in what is present day Tilaurakot, Nepal or Piprahwa, India.[note 1]

- Warder: "The Buddha [...] was born in the Sakya Republic, which was the city state of Kapilavastu, a very small state just inside the modern state boundary of Nepal against the Northern Indian frontier.[8]

- Walshe: "He belonged to the Sakya clan dwelling on the edge of the Himalayas, his actual birthplace being a few miles north of the present-day Northern Indian border, in Nepal. His father was, in fact, an elected chief of the clan rather than the king he was later made out to be, though his title was raja – a term which only partly corresponds to our word 'king'. Some of the states of North India at that time were kingdoms and others republics, and the Sakyan republic was subject to the powerful king of neighbouring Kosala, which lay to the south".[47]

- The exact location of ancient Kapilavastu is unknown.[46] It may have been either Piprahwa in Uttar Pradesh, northern India,[48][49][50] or Tilaurakot,[51] present-day Nepal.[52][46] The two cities are located only fifteen miles from each other.[52]

See also Conception and birth and Birthplace Sources</ref> He obtained his enlightenment in Bodh Gaya, gave his first sermon in Sarnath, and died in Kushinagar.

Apart from the Vedic Brahmins, the Buddha's lifetime coincided with the flourishing of influential Śramaṇa schools of thought like Ājīvika, Cārvāka, Jainism, and Ajñana.[53] Brahmajala Sutta records sixty-two such schools of thought. In this context, a śramaṇa refers to one who labors, toils, or exerts themselves (for some higher or religious purpose). It was also the age of influential thinkers like Mahavira,[54] Pūraṇa Kassapa, Makkhali Gosāla, Ajita Kesakambalī, Pakudha Kaccāyana, and Sañjaya Belaṭṭhaputta, as recorded in Samaññaphala Sutta, whose viewpoints the Buddha most certainly must have been acquainted with.[55][56][note 9] Indeed, Sariputta and Moggallāna, two of the foremost disciples of the Buddha, were formerly the foremost disciples of Sañjaya Belaṭṭhaputta, the sceptic;[58] and the Pali canon frequently depicts Buddha engaging in debate with the adherents of rival schools of thought. There is also philological evidence to suggest that the two masters, Alara Kalama and Uddaka Ramaputta, were indeed historical figures and they most probably taught Buddha two different forms of meditative techniques.[59] Thus, Buddha was just one of the many śramaṇa philosophers of that time.[60] In an era where holiness of person was judged by their level of asceticism,[61] Buddha was a reformist within the śramaṇa movement, rather than a reactionary against Vedic Brahminism.[62]

Historically, the life of the Buddha also coincided with the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley during the rule of Darius I from about 517/516 BCE.[63] This Achaemenid occupation of the areas of Gandhara and Sindh, which was to last for about two centuries, was accompanied by the introduction of Achaemenid religions, reformed Mazdaism or early Zoroastrianism, to which Buddhism might have in part reacted.[63] In particular, the ideas of the Buddha may have partly consisted in a rejection of the "absolutist" or "perfectionist" ideas contained in these Achaemenid religions.[63]

Earliest sources

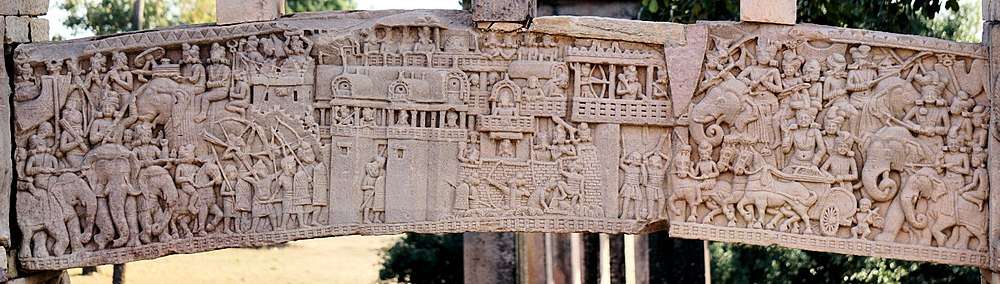

No written records about Gautama were found from his lifetime or from the one or two centuries thereafter. In the middle of the 3rd century BCE, several Edicts of Ashoka (reigned c. 269–232 BCE) mention the Buddha, and particularly Ashoka's Rummindei Minor Pillar Edict commemorates the Emperor's pilgrimage to Lumbini as the Buddha's birthplace. Another one of his edicts (Minor Rock Edict No. 3) mentions the titles of several Dhamma texts, establishing the existence of a written Buddhist tradition at least by the time of the Maurya era. These texts may be the precursor of the Pāli Canon.[64][65] [note 10]

"Sakamuni" in also mentionned in the reliefs of Bharhut, dated to circa 100 BCE, in relation with his illumination and the Bodhi tree, with the inscription Bhagavato Sakamunino Bodho ("The illumination of the Blessed Sakamuni").[66]

The oldest surviving Buddhist manuscripts are the Gandhāran Buddhist texts, reported to have been found in or around Haḍḍa near Jalalabad in eastern Afghanistan and now preserved in the British Library. They are written in the Gāndhārī language using the Kharosthi script on twenty-seven birch bark manuscripts and date from the first century BCE to the third century CE.[67]

On the basis of philological evidence, Indologist and Pali expert Oskar von Hinüber says that some of the Pali suttas have retained very archaic place-names, syntax, and historical data from close to the Buddha's lifetime, including the Mahāparinibbāṇa Sutta which contains a detailed account of the Buddha's final days. Hinüber proposes a composition date of no later than 350–320 BCE for this text, which would allow for a "true historical memory" of the events approximately 60 years prior if the Short Chronology for the Buddha's lifetime is accepted (but also reminds that such a text was originally intended more as hagiography than as an exact historical record of events).[68][69]

Traditional biographies

Biographical sources

The sources for the life of Siddhārtha Gautama are a variety of different, and sometimes conflicting, traditional biographies. These include the Buddhacarita, Lalitavistara Sūtra, Mahāvastu, and the Nidānakathā.[72] Of these, the Buddhacarita[73][74][75] is the earliest full biography, an epic poem written by the poet Aśvaghoṣa in the first century CE.[76] The Lalitavistara Sūtra is the next oldest biography, a Mahāyāna/Sarvāstivāda biography dating to the 3rd century CE.[77] The Mahāvastu from the Mahāsāṃghika Lokottaravāda tradition is another major biography, composed incrementally until perhaps the 4th century CE.[77] The Dharmaguptaka biography of the Buddha is the most exhaustive, and is entitled the Abhiniṣkramaṇa Sūtra,[78] and various Chinese translations of this date between the 3rd and 6th century CE. The Nidānakathā is from the Theravada tradition in Sri Lanka and was composed in the 5th century by Buddhaghoṣa.[79]

From canonical sources come the Jataka tales, the Mahapadana Sutta (DN 14), and the Achariyabhuta Sutta (MN 123), which include selective accounts that may be older, but are not full biographies. The Jātakas retell previous lives of Gautama as a bodhisattva, and the first collection of these can be dated among the earliest Buddhist texts.[80] The Mahāpadāna Sutta and Achariyabhuta Sutta both recount miraculous events surrounding Gautama's birth, such as the bodhisattva's descent from the Tuṣita Heaven into his mother's womb.

Nature of traditional depictions

In the earliest Buddhist texts, the nikāyas and āgamas, the Buddha is not depicted as possessing omniscience (sabbaññu)[81] nor is he depicted as being an eternal transcendent (lokottara) being. According to Bhikkhu Analayo, ideas of the Buddha's omniscience (along with an increasing tendency to deify him and his biography) are found only later, in the Mahayana sutras and later Pali commentaries or texts such as the Mahāvastu.[81] In the Sandaka Sutta, the Buddha's disciple Ananda outlines an argument against the claims of teachers who say they are all knowing [82] while in the Tevijjavacchagotta Sutta the Buddha himself states that he has never made a claim to being omniscient, instead he claimed to have the "higher knowledges" (abhijñā).[83] The earliest biographical material from the Pali Nikayas focuses on the Buddha's life as a śramaṇa, his search for enlightenment under various teachers such as Alara Kalama and his forty-five-year career as a teacher.[84]

Traditional biographies of Gautama generally include numerous miracles, omens, and supernatural events. The character of the Buddha in these traditional biographies is often that of a fully transcendent (Skt. lokottara) and perfected being who is unencumbered by the mundane world. In the Mahāvastu, over the course of many lives, Gautama is said to have developed supramundane abilities including: a painless birth conceived without intercourse; no need for sleep, food, medicine, or bathing, although engaging in such "in conformity with the world"; omniscience, and the ability to "suppress karma".[85] Nevertheless, some of the more ordinary details of his life have been gathered from these traditional sources. In modern times there has been an attempt to form a secular understanding of Siddhārtha Gautama's life by omitting the traditional supernatural elements of his early biographies.

Andrew Skilton writes that the Buddha was never historically regarded by Buddhist traditions as being merely human:

It is important to stress that, despite modern Theravada teachings to the contrary (often a sop to skeptical Western pupils), he was never seen as being merely human. For instance, he is often described as having the thirty-two major and eighty minor marks or signs of a mahāpuruṣa, "superman"; the Buddha himself denied that he was either a man or a god; and in the Mahāparinibbāna Sutta he states that he could live for an aeon were he asked to do so.[86]

The ancient Indians were generally unconcerned with chronologies, being more focused on philosophy. Buddhist texts reflect this tendency, providing a clearer picture of what Gautama may have taught than of the dates of the events in his life. These texts contain descriptions of the culture and daily life of ancient India which can be corroborated from the Jain scriptures, and make the Buddha's time the earliest period in Indian history for which significant accounts exist.[87] British author Karen Armstrong writes that although there is very little information that can be considered historically sound, we can be reasonably confident that Siddhārtha Gautama did exist as a historical figure.[88] Michael Carrithers goes a bit further by stating that the most general outline of "birth, maturity, renunciation, search, awakening and liberation, teaching, death" must be true.[89]

Biography

Conception and birth

The Buddhist tradition regards Lumbini, in present-day Nepal to be the birthplace of the Buddha.[91][note 1] He grew up in Kapilavastu.[note 1] The exact site of ancient Kapilavastu is unknown.[92] It may have been either Piprahwa, Uttar Pradesh, in present-day India,[48] or Tilaurakot, in present-day Nepal.[93] Both places belonged to the Sakya territory, and are located only 15 miles apart.[93]

Gautama was born as a Kshatriya,[94][note 12] the son of Śuddhodana, "an elected chief of the Shakya clan",[8] whose capital was Kapilavastu, and who were later annexed by the growing Kingdom of Kosala during the Buddha's lifetime. Gautama was the family name. His mother, Maya (Māyādevī), Suddhodana's wife, was a Koliyan princess. Legend has it that, on the night Siddhartha was conceived, Queen Maya dreamt that a white elephant with six white tusks entered her right side,[96][97] and ten months later[98] Siddhartha was born. As was the Shakya tradition, when his mother Queen Maya became pregnant, she left Kapilavastu for her father's kingdom to give birth. However, her son is said to have been born on the way, at Lumbini, in a garden beneath a sal tree.

The day of the Buddha's birth is widely celebrated in Theravada countries as Vesak.[99] Buddha's Birthday is called Buddha Purnima in Nepal, Bangladesh, and India as he is believed to have been born on a full moon day. Various sources hold that the Buddha's mother died at his birth, a few days or seven days later. The infant was given the name Siddhartha (Pāli: Siddhattha), meaning "he who achieves his aim". During the birth celebrations, the hermit seer Asita journeyed from his mountain abode and announced that the child would either become a great king (chakravartin) or a great sadhu.[100] By traditional account, this occurred after Siddhartha placed his feet in Asita's hair and Asita examined the birthmarks. Suddhodana held a naming ceremony on the fifth day, and invited eight Brahmin scholars to read the future. All gave a dual prediction that the baby would either become a great king or a great holy man.[100] Kondañña, the youngest, and later to be the first arhat other than the Buddha, was reputed to be the only one who unequivocally predicted that Siddhartha would become a Buddha.[101]

While later tradition and legend characterised Śuddhodana as a hereditary monarch, the descendant of the Suryavansha (Solar dynasty) of Ikṣvāku (Pāli: Okkāka), many scholars think that Śuddhodana was the elected chief of a tribal confederacy.

Early texts suggest that Gautama was not familiar with the dominant religious teachings of his time until he left on his religious quest, which is said to have been motivated by existential concern for the human condition.[102] The state of the Shakya clan was not a monarchy and seems to have been structured either as an oligarchy, or as a form of republic.[103] The more egalitarian gana-sangha form of government, as a political alternative to the strongly hierarchical kingdoms, may have influenced the development of the śramanic Jain and Buddhist sanghas, where monarchies tended toward Vedic Brahmanism.[104]

| Birth and childhood of the Buddha |

|

Early life and marriage

Siddhartha was brought up by his mother's younger sister, Maha Pajapati.[105] By tradition, he is said to have been destined by birth to the life of a prince and had three palaces (for seasonal occupation) built for him. His father, said to be King Śuddhodana, wishing for his son to be a great king, is said to have shielded him from religious teachings and from knowledge of human suffering. While Śuddhodana has traditionally been depicted as a king, and Siddhartha as his prince, more recent scholarship suggests the Shakya were in-fact organised as a semi-republican oligarchy rather than a monarchy.[106]

When he reached the age of 16, his father reputedly arranged his marriage to a cousin of the same age named Yaśodharā (Pāli: Yasodharā). According to the traditional account, she gave birth to a son, named Rāhula. Siddhartha is said to have spent 29 years as a prince in Kapilavastu. Although his father ensured that Siddhartha was provided with everything he could want or need, Buddhist scriptures say that the future Buddha felt that material wealth was not life's ultimate goal.[105]

Renunciation and ascetic life

At the age of 29, Siddhartha left his palace to meet his subjects. Despite his father's efforts to hide from him the sick, aged and suffering, Siddhartha was said to have seen an old man. When his charioteer Channa explained to him that all people grew old, the prince went on further trips beyond the palace. On these he encountered a diseased man, a decaying corpse, and an ascetic. These depressed him, and he initially strove to overcome ageing, sickness, and death by living the life of an ascetic.[107]

Accompanied by Channa and riding his horse Kanthaka, Gautama quit his palace for the life of a mendicant. It's said that "the horse's hooves were muffled by the gods"[108] to prevent guards from knowing of his departure.

Gautama initially went to Rajagaha and began his ascetic life by begging for alms in the street. After King Bimbisara's men recognised Siddhartha and the king learned of his quest, Bimbisara offered Siddhartha the throne. Siddhartha rejected the offer but promised to visit his kingdom of Magadha first, upon attaining enlightenment.

He left Rajagaha and practised under two hermit teachers of yogic meditation.[109][110][111] After mastering the teachings of Alara Kalama (Skr. Ārāḍa Kālāma), he was asked by Kalama to succeed him. However, Gautama felt unsatisfied by the practice, and moved on to become a student of yoga with Udaka Ramaputta (Skr. Udraka Rāmaputra).[112] With him he achieved high levels of meditative consciousness and was again asked to succeed his teacher. But, once more, he was not satisfied, and again moved on.[113]

Awakening

According to the early Buddhist texts,[114] after realising that meditative dhyana was the right path to awakening, but that extreme asceticism didn't work, Gautama discovered what Buddhists know as being, the Middle Way[114]—a path of moderation away from the extremes of self-indulgence and self-mortification, or the Noble Eightfold Path, as described in the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta, which is regarded as the first discourse of the Buddha.[114] In a famous incident, after becoming starved and weakened, he is said to have accepted milk and rice pudding from a village girl named Sujata.[115] Such was his emaciated appearance that she wrongly believed him to be a spirit that had granted her a wish.[115]

Following this incident, Gautama was famously seated under a pipal tree—now known as the Bodhi tree—in Bodh Gaya, India, when he vowed never to arise until he had found the truth.[116] Kaundinya and four other companions, believing that he had abandoned his search and become undisciplined, ceased to stay with him, and went to somewhere else. After a reputed 49 days of meditation, at the age of 35, he is said to have attained Enlightenment,[116][117] and became known as the Buddha or "Awakened One" ("Buddha" is also sometimes translated as "The Enlightened One").

According to some sutras of the Pali canon, at the time of his awakening he realised complete insight into the Four Noble Truths, thereby attaining liberation from samsara, the endless cycle of rebirth, suffering and dying again.[118][119][120] According to scholars, this story of the awakening and the stress on "liberating insight" is a later development in the Buddhist tradition, where the Buddha may have regarded the practice of dhyana as leading to nirvana and moksha.[121][122][118][note 13]

Nirvana is the extinguishing of the "fires" of desire, hatred, and ignorance, that keep the cycle of suffering and rebirth going.[123] Nirvana is also regarded as the "end of the world", in that no personal identity or boundaries of the mind remain. In such a state, a being is said to possess the Ten Characteristics, belonging to every Buddha.

According to a story in the Āyācana Sutta (Samyutta Nikaya VI.1)—a scripture found in the Pāli and other canons—immediately after his awakening, the Buddha debated whether or not he should teach the Dharma to others. He was concerned that humans were so overpowered by ignorance, greed and hatred that they could never recognise the path, which is subtle, deep and hard to grasp. However, in the story, Brahmā Sahampati convinced him, arguing that at least some will understand it. The Buddha relented, and agreed to teach.

Formation of the sangha

After his awakening, the Buddha met Taphussa and Bhallika—two merchant brothers from the city of Balkh in what is currently Afghanistan—who became his first lay disciples. It is said that each was given hairs from his head, which are now claimed to be enshrined as relics in the Shwe Dagon Temple in Rangoon, Burma. The Buddha intended to visit Asita, and his former teachers, Alara Kalama and Udaka Ramaputta, to explain his findings, but they had already died.

He then travelled to the Deer Park near Varanasi (Benares) in northern India, where he set in motion what Buddhists call the Wheel of Dharma by delivering his first sermon to the five companions with whom he had sought enlightenment. Together with him, they formed the first saṅgha: the company of Buddhist monks.

All five become arahants, and within the first two months, with the conversion of Yasa and fifty-four of his friends, the number of such arahants is said to have grown to 60. The conversion of three brothers named Kassapa followed, with their reputed 200, 300 and 500 disciples, respectively. This swelled the sangha to more than 1,000.

Travels and teaching

For the remaining 45 years of his life, the Buddha is said to have travelled in the Gangetic Plain, in what is now Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and southern Nepal, teaching a diverse range of people: from nobles to servants, murderers such as Angulimala, and cannibals such as Alavaka.[124] Although the Buddha's language remains unknown, it's likely that he taught in one or more of a variety of closely related Middle Indo-Aryan dialects, of which Pali may be a standardisation.

The sangha travelled through the subcontinent, expounding the dharma. This continued throughout the year, except during the four months of the Vassa rainy season when ascetics of all religions rarely travelled. One reason was that it was more difficult to do so without causing harm to animal life. At this time of year, the sangha would retreat to monasteries, public parks or forests, where people would come to them.

The first vassana was spent at Varanasi when the sangha was formed. After this, the Buddha kept a promise to travel to Rajagaha, capital of Magadha, to visit King Bimbisara. During this visit, Sariputta and Maudgalyayana were converted by Assaji, one of the first five disciples, after which they were to become the Buddha's two foremost followers. The Buddha spent the next three seasons at Veluvana Bamboo Grove monastery in Rajagaha, the capital of Magadha.

Upon hearing of his son's awakening, Suddhodana sent, over a period, ten delegations to ask him to return to Kapilavastu. On the first nine occasions, the delegates failed to deliver the message and instead joined the sangha to become arahants. The tenth delegation, led by Kaludayi, a childhood friend of Gautama's (who also became an arahant), however, delivered the message.

Now two years after his awakening, the Buddha agreed to return, and made a two-month journey by foot to Kapilavastu, teaching the dharma as he went. At his return, the royal palace prepared a midday meal, but the sangha was making an alms round in Kapilavastu. Hearing this, Suddhodana approached his son, the Buddha, saying:

"Ours is the warrior lineage of Mahamassata, and not a single warrior has gone seeking alms."

The Buddha is said to have replied:

"That is not the custom of your royal lineage. But it is the custom of my Buddha lineage. Several thousands of Buddhas have gone by seeking alms."

Buddhist texts say that Suddhodana invited the sangha into the palace for the meal, followed by a dharma talk. After this he is said to have become a sotapanna. During the visit, many members of the royal family joined the sangha. The Buddha's cousins Ananda and Anuruddha became two of his five chief disciples. At the age of seven, his son Rahula also joined, and became one of his ten chief disciples. His half-brother Nanda also joined and became an arahant.

Of the Buddha's disciples, Sariputta, Maudgalyayana, Mahakasyapa, Ananda and Anuruddha are believed to have been the five closest to him. His ten foremost disciples were reputedly completed by the quintet of Upali, Subhoti, Rahula, Mahakaccana and Punna.

In the fifth vassana, the Buddha was staying at Mahavana near Vesali when he heard news of the impending death of his father. He is said to have gone to Suddhodana and taught the dharma, after which his father became an arahant.

The king's death and cremation was to inspire the creation of an order of nuns. Buddhist texts record that the Buddha was reluctant to ordain women. His foster mother Maha Pajapati, for example, approached him, asking to join the sangha, but he refused. Maha Pajapati, however, was so intent on the path of awakening that she led a group of royal Sakyan and Koliyan ladies, which followed the sangha on a long journey to Rajagaha. In time, after Ananda championed their cause, the Buddha is said to have reconsidered and, five years after the formation of the sangha, agreed to the ordination of women as nuns. He reasoned that males and females had an equal capacity for awakening. But he gave women additional rules (Vinaya) to follow.

Mahaparinirvana

According to the Mahaparinibbana Sutta of the Pali canon, at the age of 80, the Buddha announced that he would soon reach parinirvana, or the final deathless state, and abandon his earthly body. After this, the Buddha ate his last meal, which he had received as an offering from a blacksmith named Cunda. Falling violently ill, Buddha instructed his attendant Ānanda to convince Cunda that the meal eaten at his place had nothing to do with his passing and that his meal would be a source of the greatest merit as it provided the last meal for a Buddha.[125] Mettanando and von Hinüber argue that the Buddha died of mesenteric infarction, a symptom of old age, rather than food poisoning.[126][127]

The precise contents of the Buddha's final meal are not clear, due to variant scriptural traditions and ambiguity over the translation of certain significant terms; the Theravada tradition generally believes that the Buddha was offered some kind of pork, while the Mahayana tradition believes that the Buddha consumed some sort of truffle or other mushroom. These may reflect the different traditional views on Buddhist vegetarianism and the precepts for monks and nuns.

Waley suggests that Theravadins would take suukaramaddava (the contents of the Buddha's last meal), which can translate literally as pig-soft, to mean "soft flesh of a pig" or "pig's soft-food", that is, after Neumann, a soft food favoured by pigs, assumed to be a truffle. He argues (also after Neumann) that as "(p)lant names tend to be local and dialectical", as there are several plants known to have suukara- (pig) as part of their names,[note 14] and as Pali Buddhism developed in an area remote from the Buddha's death, suukaramaddava could easily have been a type of plant whose local name was unknown to those in Pali regions. Specifically, local writers writing soon after the Buddha's death knew more about their flora than Theravadin commentator Buddhaghosa who lived hundreds of years and hundreds of kilometres remote in time and space from the events described. Unaware that it may have been a local plant name and with no Theravadin prohibition against eating animal flesh, Theravadins would not have questioned the Buddha eating meat and interpreted the term accordingly.[128]

According to Buddhist tradition, the Buddha died at Kuśināra (present-day Kushinagar, India), which became a pilgrimage centre.[129] Ananda protested the Buddha's decision to enter parinirvana in the abandoned jungles of Kuśināra of the Malla kingdom. The Buddha, however, is said to have reminded Ananda how Kushinara was a land once ruled by a righteous wheel-turning king and the appropriate place for him to die.[130]

The Buddha then asked all the attendant Bhikkhus to clarify any doubts or questions they had and cleared them all in a way which others could not do. They had none. According to Buddhist scriptures, he then finally entered parinirvana. The Buddha's final words are reported to have been: "All composite things (Saṅkhāra) are perishable. Strive for your own liberation with diligence" (Pali: 'vayadhammā saṅkhārā appamādena sampādethā'). His body was cremated and the relics were placed in monuments or stupas, some of which are believed to have survived until the present. For example, the Temple of the Tooth or "Dalada Maligawa" in Sri Lanka is the place where what some believe to be the relic of the right tooth of Buddha is kept at present.

According to the Pāli historical chronicles of Sri Lanka, the Dīpavaṃsa and Mahāvaṃsa, the coronation of Emperor Aśoka (Pāli: Asoka) is 218 years after the death of the Buddha. According to two textual records in Chinese (十八部論 and 部執異論), the coronation of Emperor Aśoka is 116 years after the death of the Buddha. Therefore, the time of Buddha's passing is either 486 BCE according to Theravāda record or 383 BCE according to Mahayana record. However, the actual date traditionally accepted as the date of the Buddha's death in Theravāda countries is 544 or 545 BCE, because the reign of Emperor Aśoka was traditionally reckoned to be about 60 years earlier than current estimates. In Burmese Buddhist tradition, the date of the Buddha's death is 13 May 544 BCE.[131] whereas in Thai tradition it is 11 March 545 BCE.[132]

At his death, the Buddha is famously believed to have told his disciples to follow no leader. Mahakasyapa was chosen by the sangha to be the chairman of the First Buddhist Council, with the two chief disciples Maudgalyayana and Sariputta having died before the Buddha.

While in the Buddha's days he was addressed by the very respected titles Buddha, Shākyamuni, Shākyasimha, Bhante and Bho, he was known after his parinirvana nirvana as Arihant, Bhagavā/Bhagavat/Bhagwān, Mahāvira,[133] Jina/Jinendra, Sāstr, Sugata, and most popularly in scriptures as Tathāgata.

Relics

After his death, Buddha's cremation relics were divided amongst 8 royal families and his disciples; centuries later they would be enshrined by King Ashoka into 84,000 stupas.[134][135] Many supernatural legends surround the history of alleged relics as they accompanied the spread of Buddhism and gave legitimacy to rulers.

Physical characteristics

An extensive and colourful physical description of the Buddha has been laid down in scriptures. A kshatriya by birth, he had military training in his upbringing, and by Shakyan tradition was required to pass tests to demonstrate his worthiness as a warrior in order to marry. He had a strong enough body to be noticed by one of the kings and was asked to join his army as a general. He is also believed by Buddhists to have "the 32 Signs of the Great Man".

The Brahmin Sonadanda described him as "handsome, good-looking, and pleasing to the eye, with a most beautiful complexion. He has a godlike form and countenance, he is by no means unattractive." (D, I:115)

"It is wonderful, truly marvellous, how serene is the good Gotama's appearance, how clear and radiant his complexion, just as the golden jujube in autumn is clear and radiant, just as a palm-tree fruit just loosened from the stalk is clear and radiant, just as an adornment of red gold wrought in a crucible by a skilled goldsmith, deftly beaten and laid on a yellow-cloth shines, blazes and glitters, even so, the good Gotama's senses are calmed, his complexion is clear and radiant." (A, I:181)

A disciple named Vakkali, who later became an arahant, was so obsessed by the Buddha's physical presence that the Buddha is said to have felt impelled to tell him to desist, and to have reminded him that he should know the Buddha through the Dhamma and not through physical appearances.

Although there are no extant representations of the Buddha in human form until around the 1st century CE (see Buddhist art), descriptions of the physical characteristics of fully enlightened buddhas are attributed to the Buddha in the Digha Nikaya's Lakkhaṇa Sutta (D, I:142).[137] In addition, the Buddha's physical appearance is described by Yasodhara to their son Rahula upon the Buddha's first post-Enlightenment return to his former princely palace in the non-canonical Pali devotional hymn, Narasīha Gāthā ("The Lion of Men").[138]

Among the 32 main characteristics it is mentioned that Buddha has blue eyes.[139]

Nine virtues

Recollection of nine virtues attributed to the Buddha is a common Buddhist meditation and devotional practice called Buddhānusmṛti. The nine virtues are also among the 40 Buddhist meditation subjects. The nine virtues of the Buddha appear throughout the Tipitaka,[140] and include:

- Buddho – Awakened

- Sammasambuddho – Perfectly self-awakened

- Vijja-carana-sampano – Endowed with higher knowledge and ideal conduct.

- Sugato – Well-gone or Well-spoken.

- Lokavidu – Wise in the knowledge of the many worlds.

- Anuttaro Purisa-damma-sarathi – Unexcelled trainer of untrained people.

- Satthadeva-Manussanam – Teacher of gods and humans.

- Bhagavathi – The Blessed one

- Araham – Worthy of homage. An Arahant is "one with taints destroyed, who has lived the holy life, done what had to be done, laid down the burden, reached the true goal, destroyed the fetters of being, and is completely liberated through final knowledge."

Teachings

Use of Brahmanical motifs

In the Pali Canon, the Buddha uses many Brahmanical devices. For example, in Samyutta Nikaya 111, Majjhima Nikaya 92 and Vinaya i 246 of the Pali Canon, the Buddha praises the Agnihotra as the foremost sacrifice and the Gayatri mantra as the foremost meter:

aggihuttamukhā yaññā sāvittī chandaso mukham.

Sacrifices have the Agnihotra as foremost; of meter, the foremost is the Sāvitrī.[141]

Tracing the oldest teachings

One method to obtain information on the oldest core of Buddhism is to compare the oldest versions of the Pali Canon and other texts, such as the surviving portions of Sarvastivada, Mulasarvastivada, Mahisasaka, Dharmaguptaka,[142][143] and the Chinese Agamas. The reliability of these sources, and the possibility of drawing out a core of oldest teachings, is a matter of dispute..[144][145][146][147] According to Vetter, inconsistencies remain, and other methods must be applied to resolve those inconsistencies.[142][note 15]

According to Schmithausen, there are three positions held by scholars of Buddhism:[150]

Dhyana and insight

A core problem in the study of early Buddhism is the relation between dhyana and insight.[145][144][147] Schmithausen notes that the mention of the four noble truths as constituting "liberating insight", which is attained after mastering the Rupa Jhanas, is a later addition to texts such as Majjhima Nikaya 36.[148][144][145]

Earliest Buddhism

According to Tilmann Vetter, the core of earliest Buddhism is the practice of dhyāna,[155] as a workable alternative to painful ascetic practices.[156][note 20] Bronkhorst agrees that Dhyāna was a Buddhist invention,[144] whereas Norman notes that "the Buddha's way to release [...] was by means of meditative practices."[158] Discriminating insight into transiency as a separate path to liberation was a later development.[159][160]

According to the Mahāsaccakasutta,[note 21] from the fourth jhana the Buddha gained bodhi. Yet, it is not clear what he was awakened to.[158][144] According to Schmithausen and Bronkhorst, "liberating insight" is a later addition to this text, and reflects a later development and understanding in early Buddhism.[148][144] The mentioning of the four truths as constituting "liberating insight" introduces a logical problem, since the four truths depict a linear path of practice, the knowledge of which is in itself not depicted as being liberating:[161]

[T]hey do not teach that one is released by knowing the four noble truths, but by practicing the fourth noble truth, the eightfold path, which culminates in right samadhi.[161]

Although "Nibbāna" (Sanskrit: Nirvāna) is the common term for the desired goal of this practice, many other terms can be found throughout the Nikayas, which are not specified.[162][note 22]

According to Vetter, the description of the Buddhist path may initially have been as simple as the term "the middle way". In time, this short description was elaborated, resulting in the description of the eightfold path.[163]

According to both Bronkhorst and Anderson, the four truths became a substitution for prajna, or "liberating insight", in the suttas[122][118] in those texts where "liberating insight" was preceded by the four jhanas.[164] According to Bronkhorst, the four truths may not have been formulated in earliest Buddhism, and did not serve in earliest Buddhism as a description of "liberating insight".[165] Gotama's teachings may have been personal, "adjusted to the need of each person."[164]

The three marks of existence[note 23] may reflect Upanishadic or other influences. K.R. Norman supposes that these terms were already in use at the Buddha's time, and were familiar to his listeners.[166]

The Brahma-vihara was in origin probably a brahmanic term;[167] but its usage may have been common to the Sramana traditions.[144]

Later developments

In time, "liberating insight" became an essential feature of the Buddhist tradition. The following teachings, which are commonly seen as essential to Buddhism, are later formulations which form part of the explanatory framework of this "liberating insight":[145][144]

- The Four Noble Truths: that suffering is an ingrained part of existence; that the origin of suffering is craving for sensuality, acquisition of identity, and fear of annihilation; that suffering can be ended; and that following the Noble Eightfold Path is the means to accomplish this;

- The Noble Eightfold Path: right view, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration;

- Dependent origination: the mind creates suffering as a natural product of a complex process.

Other religions

Some Hindus regard Gautama as the 9th avatar of Vishnu.[note 11][168] However, Buddha's teachings deny the authority of the Vedas and the concepts of Brahman-Atman.[169][170][171] Consequently Buddhism is generally classified as a nāstika school (heterodox, literally "It is not so"[note 24]) in contrast to the six orthodox schools of Hinduism.[174][175][176]

The Buddha is regarded as a prophet by the minority Ahmadiyya[177] sect of Muslims—a sect considered a deviant and rejected as apostate by mainstream Islam.[178][179] Some early Chinese Taoist-Buddhists thought the Buddha to be a reincarnation of Laozi.[180]

Disciples of the Cao Đài religion worship the Buddha as a major religious teacher.[181] His image can be found in both their Holy See and on the home altar. He is revealed during communication with Divine Beings as son of their Supreme Being (God the Father) together with other major religious teachers and founders like Jesus, Laozi, and Confucius.[182]

The Christian Saint Josaphat is based on the Buddha. The name comes from the Sanskrit Bodhisattva via Arabic Būdhasaf and Georgian Iodasaph.[183] The only story in which St. Josaphat appears, Barlaam and Josaphat, is based on the life of the Buddha.[184] Josaphat was included in earlier editions of the Roman Martyrology (feast day 27 November)—though not in the Roman Missal—and in the Eastern Orthodox Church liturgical calendar (26 August).

In the ancient Gnostic sect of Manichaeism, the Buddha is listed among the prophets who preached the word of God before Mani.[185]

In Sikhism, Buddha is mentioned as the 23rd avatar of Vishnu in the Chaubis Avtar, a composition in Dasam Granth traditionally and historically attributed to Guru Gobind Singh.[186]

Depiction in arts and media

- Films

- Little Buddha, a 1994 film by Bernardo Bertolucci

- Prem Sanyas, a 1925 silent film, directed by Franz Osten and Himansu Rai

- Television

- Buddha, a 2013 mythological drama on Zee TV

- Literature

- The Light of Asia, an 1879 epic poem by Edwin Arnold

- Buddha, a manga series that ran from 1972 to 1983 by Osamu Tezuka

- Siddhartha novel by Hermann Hesse, written in German in 1922

- Lord of Light, a novel by Roger Zelazny depicts a man in a far future Earth Colony who takes on the name and teachings of the Buddha

- Creation, a 1981 novel by Gore Vidal, includes the Buddha as one of the religious figures that the main character encounters

- Music

- Karuna Nadee, a 2010 oratorio by Dinesh Subasinghe

- The Light of Asia, an 1886 oratorio by Dudley Buck

Painting

- Shussan Shaka, a Zen painting motif

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 According to the Buddhist tradition, following the Nidanakatha,[38] the introductory to the Jataka tales, the stories of the former lives of the Buddha, Gautama was born in Lumbini, present-day Nepal.[39][40] In the mid-3rd century BCE the Emperor Ashoka determined that Lumbini was Gautama's birthplace and thus installed a pillar there with the inscription: "...this is where the Buddha, sage of the Śākyas (Śākyamuni), was born."[41]

Based on stone inscriptions, there is also speculation that Lumbei, Kapileswar village, Odisha, at the east coast of India, was the site of ancient Lumbini.[42][43][44] Hartmann discusses the hypothesis and states, "The inscription has generally been considered spurious (...)"[45] He quotes Sircar: "There can hardly be any doubt that the people responsible for the Kapilesvara inscription copied it from the said facsimile not much earlier than 1928."

Kapilavastu was the place where he grew up:[46][note 8] Gethin does not give references for this statement. - ↑ According to Mahaparinibbana Sutta,[3] Gautama died in Kushinagar, which is located in present-day Uttar Pradesh, India.

- ↑ /ˈɡɔːtəmə,

ˈɡaʊ- ˈbuːdə, ˈbʊdə/ - ↑ /sɪˈdɑːrtə,

-θə/ ; Sanskrit: [sid̪ːʱɑːrt̪ʰə gəut̪əmə]; Gautama namely Gotama in Pali - ↑ Sanskrit: [ɕɑːkjəmun̪i bud̪ːʱə]

- 1 2

- 411–400: Dundas 2002, p. 24: "...as is now almost universally accepted by informed Indological scholarship, a re-examination of early Buddhist historical material, [...], necessitates a redating of the Buddha's death to between 411 and 400 BCE..."

- 405: Richard Gombrich[27][25][28][29]

- Around 400: See the consensus in the essays by leading scholars in Narain, Awadh Kishore, ed. (2003), The Date of the Historical Śākyamuni Buddha, New Delhi: BR Publishing, ISBN 8176463531 .

- According to Pali scholar K. R. Norman, a life span for the Buddha of c. 480 to 400 BCE (and his teaching period roughly from c. 445 to 400 BCE) "fits the archaeological evidence better".[30] See also Notes on the Dates of the Buddha Íåkyamuni.

- ↑ In 2013, archaeologist Robert Coningham found the remains of a Bodhigara, a tree shrine, dated to 550 BCE at the Maya Devi Temple, Lumbini, speculating that it may possible be a Buddhist shrine. If so, this may push back the Buddha's birth date.[33] Archaeologists caution that the shrine may represent pre-Buddhist tree worship, and that further research is needed.[33]

Richard Gombrich has dismissed Coningham's speculations as "a fantasy", noting that Coningham lacks the necessary expertise on the history of early Buddhism.[34]

Geoffrey Samuels notes that several locations of both early Buddhism and Jainism are closely related to Yaksha-worship, that several Yakshas were "converted" to Buddhism, a well-known example being Vajrapani,[35] and that several Yaksha-shrines, where trees were worshipped, were converted into Buddhist holy places.[36] - ↑ Some sources mention Kapilavastu as the birthplace of the Buddha. Gethin states: "The earliest Buddhist sources state that the future Buddha was born Siddhārtha Gautama (Pali Siddhattha Gotama), the son of a local chieftain—a rājan—in Kapilavastu (Pali Kapilavatthu) what is now the Indian–Nepalese border."<ref name='FOOTNOTEGethin199814'>Gethin 1998, p. 14.

- ↑ According to Alexander Berzin, "Buddhism developed as a shramana school that accepted rebirth under the force of karma, while rejecting the existence of the type of soul that other schools asserted. In addition, the Buddha accepted as parts of the path to liberation the use of logic and reasoning, as well as ethical behavior, but not to the degree of Jain asceticism. In this way, Buddhism avoided the extremes of the previous four shramana schools."[57]

- ↑ Minor Rock Edict Nb3: "These Dhamma texts – Extracts from the Discipline, the Noble Way of Life, the Fears to Come, the Poem on the Silent Sage, the Discourse on the Pure Life, Upatisa's Questions, and the Advice to Rahula which was spoken by the Buddha concerning false speech – these Dhamma texts, reverend sirs, I desire that all the monks and nuns may constantly listen to and remember. Likewise the laymen and laywomen."[64]

Dhammika:"There is disagreement amongst scholars concerning which Pali suttas correspond to some of the text. Vinaya samukose: probably the Atthavasa Vagga, Anguttara Nikaya, 1:98–100. Aliya vasani: either the Ariyavasa Sutta, Anguttara Nikaya, V:29, or the Ariyavamsa Sutta, Anguttara Nikaya, II: 27–28. Anagata bhayani: probably the Anagata Sutta, Anguttara Nikaya, III:100. Muni gatha: Muni Sutta, Sutta Nipata 207–221. Upatisa pasine: Sariputta Sutta, Sutta Nipata 955–975. Laghulavade: Rahulavada Sutta, Majjhima Nikaya, I:421."[64] - 1 2 Kumar Singh, Nagendra (1997). "Buddha as depicted in the Purāṇas". Encyclopaedia of Hinduism. 7. Anmol Publications. pp. 260–75. ISBN 978-8174881687. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ↑ According to Geoffrey Samuel, the Buddha was born as a Kshatriya,[94] in a moderate Vedic culture at the central Ganges Plain area, where the shramana-traditions developed. This area had a moderate Vedic culture, where the Kshatriyas were the highest varna, in contrast to the Brahmanic ideology of Kuru–Panchala, where the Brahmins had become the highest varna.[94] Both the Vedic culture and the shramana tradition contributed to the emergence of the so-called "Hindu-synthesis" around the start of the Common Era.[95][94]

- ↑ Scholars have noted inconsistencies in the presentations of the Buddha's enlightenment, and the Buddhist path to liberation, in the oldest sutras. These inconsistencies show that the Buddhist teachings evolved, either during the lifetime of the Buddha, or thereafter. See:

* Andre Bareau (1963), Recherches sur la biographie du Buddha dans les Sutrapitaka et les Vinayapitaka anciens, Ecole Francaise d'Extreme-Orient

* Schmithausen, On some Aspects of Descriptions or Theories of 'Liberating Insight' and 'Enlightenment' in Early Buddhism

* K.R. Norman, Four Noble Truths

* Tilman Vetter, The Ideas and Meditative Practices of Early Buddhism

* Richard F. Gombrich (2006). "4". How Buddhism Began: The Conditioned Genesis of the Early Teachings. Routledge. ISBN 978-1134196395.

* Bronkhorst, Johannes (1993), "7", The Two Traditions Of Meditation In Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers

* Anderson, Carol (1999), Pain and Its Ending: The Four Noble Truths in the Theravada Buddhist Canon, Routledge - ↑ Waley notes: suukara-kanda, "pig-bulb"; suukara-paadika, "pig's foot" and sukaresh.ta "sought-out by pigs". He cites Neumann's suggestion that if a plant called "sought-out by pigs" exists then suukaramaddava can mean "pig's delight".

- ↑ Exemplary studies are the study on descriptions of "liberating insight" by Lambert Schmithausen,[148] the overview of early Buddhism by Tilmann Vetter,[145] the philological work on the four truths by K.R. Norman,[149] the textual studies by Richard Gombrich,[147] and the research on early meditation methods by Johannes Bronkhorst.[144]

- ↑ Two well-known proponent of this position are A.K. Warder and Richard Gombrich.

* According to A.K. Warder, in his 1970 publication "Indian Buddhism},"from the oldest extant texts a common kernel can be drawn out.[151] According to Warder, c.q. his publisher: "This kernel of doctrine is presumably common Buddhism of the period before the great schisms of the fourth and third centuries BC. It may be substantially the Buddhism of the Buddha himself, although this cannot be proved: at any rate it is a Buddhism presupposed by the schools as existing about a hundred years after the parinirvana of the Buddha, and there is no evidence to suggest that it was formulated by anyone else than the Buddha and his immediate followers".[151]

* Richard Gombrich: "I have the greatest difficulty in accepting that the main edifice is not the work of a single genius. By "the main edifice" I mean the collections of the main body of sermons, the four Nikāyas, and of the main body of monastic rules."[147] - ↑ A proponent of the second position is Ronald Davidson.

- ↑ Ronald Davidson: "While most scholars agree that there was a rough body of sacred literature (disputed)(sic) that a relatively early community (disputed)(sic) maintained and transmitted, we have little confidence that much, if any, of surviving Buddhist scripture is actually the word of the historic Buddha."[152]

- ↑ Well-known proponents of the third position are:

* J.W. de Jong: "It would be hypocritical to assert that nothing can be said about the doctrine of earliest Buddhism [...] the basic ideas of Buddhism found in the canonical writings could very well have been proclaimed by him [the Buddha], transmitted and developed by his disciples and, finally, codified in fixed formulas."[153]

* Johannes Bronkhorst: "This position is to be preferred to (ii) for purely methodological reasons: only those who seek may find, even if no success is guaranteed."[150]

* Donald Lopez: "The original teachings of the historical Buddha are extremely difficult, if not impossible, to recover or reconstruct."[154] - ↑ Vetter: "However, if we look at the last, and in my opinion the most important, component of this list [the noble eightfold path], we are still dealing with what according to me is the real content of the middle way, dhyana-meditation, at least the stages two to four, which are said to be free of contemplation and reflection. Everything preceding the eighth part, i.e. right samadhi, apparently has the function of preparing for the right samadhi."[157]

- ↑ Majjhima Nikaya 36

- ↑ Vetter: "I am especially thinking here of MN 26 (I p.163,32; 165,15;166,35) kimkusalagavesi anuttaram santivarapadam pariyesamano (searching for that which is beneficial, seeking the unsurpassable, best place of peace) and again MN 26 (passim), anuttaramyagakkhemam nibbiinam pariyesati (he seeks the unsurpassable safe place, the nirvana). Anuppatta-sadattho (one who has reached the right goal) is also a vague positive expression in the Arhatformula in MN 35 (I p, 235), see chapter 2, footnote 3, Furthermore, satthi (welfare) is important in e.g. SN 2.12 or 2.17 or Sn 269; and sukha and rati (happiness), in contrast to other places, as used in Sn 439 and 956. The oldest term was perhaps amata (immortal, immortality) [...] but one could say here that it is a negative term."[162]

- ↑ Understanding of these marks helps in the development of detachment:

- ↑ "in Sanskrit philosophical literature, 'āstika' means 'one who believes in the authority of the Vedas', 'soul', 'Brahman'. ('nāstika' means the opposite of these).[172][173]

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 Cousins 1996, pp. 57–63.

- ↑ Norman 1997, p. 33.

- ↑ "Maha-parinibbana Sutta", Digha Nikaya (16), Access insight, part 5

- 1 2 Baroni 2002, p. 230.

- ↑ Dhirasekera, Jotiya. Buddhist monastic discipline. Buddhist Cultural Centre, 2007.

- ↑ Shults, Brett. "A Note on Śramaṇa in Vedic Texts." Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies 10 (2016).

- ↑ Boeree, C George. "An Introduction to Buddhism". Shippensburg University. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Warder 2000, p. 45.

- ↑ Laumakis 2008, p. 4.

- ↑ Skilton 2004, p. 41.

- ↑ Charles Russell Coulter (2013). Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities. Routledge. p. 109. ISBN 978-1135963903.

According to some, Buddha was the ninth avatar of Vishnu. Buddhists do not accept this theory.

- ↑ Holt, John Clifford (2008). The Buddhist Viṣṇu: Religious Transformation, Politics, and Culture. Motilal Banarsidass Publishe. ISBN 978-8120832695.

- ↑ Jones, Constance; Ryan, James D. (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0816075645.

- ↑ Rawlinson, Hugh George. (1950) A Concise History of the Indian People, Oxford University Press. p. 46.

- ↑ Muller, F. Max. (2001) The Dhammapada And Sutta-nipata, Routledge (UK). p. xlvii. ISBN 0700715487.

- ↑ India: A History. Revised and Updated, by John Keay: "The date [of Buddha's meeting with Bimbisara] (given the Buddhist 'short chronology') must have been around 400 BCE."

- ↑ Smith 1924, pp. 34, 48.

- ↑ Schumann 2003, pp. 1–5.

- ↑ Carrithers 2001, p. 3.

- ↑ Buswell 2003, p. 352.

- ↑ Lopez 1995, p. 16.

- ↑ Schumann 2003, pp. 10–13.

- ↑ Bechert 1991–1997.

- ↑ Ruegg 1999, pp. 82–87.

- 1 2 Narain 1993, pp. 187–201.

- ↑ Prebish 2008, p. 2.

- ↑ Gombrich 1992.

- ↑ Hartmann 1991.

- ↑ Gombrich 2000.

- ↑ Norman 1997, p. 39.

- ↑ Schumann 2003, p. xv.

- ↑ Wayman 1993, pp. 37–58.

- 1 2 Vergano, Dan (25 November 2013). "Oldest Buddhist Shrine Uncovered In Nepal May Push Back the Buddha's Birth Date". National Geographic. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ Gombrich, Richard (2013), Recent discovery of "earliest Buddhist shrine" a sham?, Tricycle

- ↑ Tan, Piya (2009-12-21), Ambaṭṭha Sutta. Theme: Religious arrogance versus spiritual openness (PDF), Dharma farer

- ↑ Samuels 2010, pp. 140–52.

- 1 2 Gombrich 1988, p. 49.

- ↑ Davids, Rhys, ed. (1878), Buddhist birth-stories; Jataka tales. The commentary introd. entitled Nidanakatha; the story of the lineage. Translated from V. Fausböll's ed. of the Pali text by TW Rhys Davids (new & rev. ed.)

- ↑ "Lumbini, the Birthplace of the Lord Buddha". UNESCO. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- ↑ "The Astamahapratiharya: Buddhist pilgrimage sites". Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ↑ Gethin 1998, p. 19.

- ↑ Mahāpātra 1977.

- ↑ Mohāpātra 2000, p. 114.

- ↑ Tripathy 2014.

- ↑ Hartmann 1991, pp. 38–39.

- 1 2 3 Keown & Prebish 2013, p. 436.

- ↑ Walshe 1995, p. 20.

- 1 2 Nakamura 1980, p. 18.

- ↑ Srivastava 1979, pp. 61–74.

- ↑ Srivastava 1980, p. 108.

- ↑ Tuladhar 2002, pp. 1–7.

- 1 2 Huntington 1986.

- ↑ Jayatilleke 1963, chpt. 1–3.

- ↑ Clasquin-Johnson, Michel. "Will the real Nigantha Nātaputta please stand up? Reflections on the Buddha and his contemporaries". Journal for the Study of Religion. 28 (1): 100–14. ISSN 1011-7601.

- ↑ Walshe 1995, p. 268.

- ↑ Collins 2009, pp. 199–200.

- ↑ Berzin, Alexander (April 2007). "Indian Society and Thought before and at the Time of Buddha". Study Buddhism. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ↑ Nakamura 1980, p. 20.

- ↑ Wynne 2007, pp. 8–23, ch. 2.

- ↑ Warder 1998, p. 45.

- ↑ Roy 1984, p. 1.

- ↑ Roy 1984, p. 7.

- 1 2 3 Beckwith, Christopher I. (2015). Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia. Princeton University Press. p. 7-12. ISBN 9781400866328.

- 1 2 3 Dhammika 1993.

- ↑ Bhikkhu, Thanissaro. "That the True Dhamma Might Last a Long Time: Readings Selected by King Asoka". Access to Insight. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- 1 2 Leoshko, Janice (2017). Sacred Traces: British Explorations of Buddhism in South Asia. Routledge. p. 64. ISBN 9781351550307.

- ↑ "Ancient Buddhist Scrolls from Gandhara". UW Press. Retrieved 4 September 2008.

- ↑ Oskar von Hinüber "Hoary past and hazy memory. On the history of early Buddhist texts", in Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, Volume 29, Number 2: 2006 (2008), pp. 198–206

- ↑ see also: Michael Witzel, (2009), "Moving Targets? Texts, language, archaeology and history in the Late Vedic and early Buddhist periods." in Indo-Iranian Journal 52(2–3): 287–310.

- ↑ "The earliest anthropomorphic representation of the Buddha that we know so far, the Bimaran reliquary" Yaldiz, Marianne (1987). Investigating Indian Art. Staatl. Museen Preuss. Kulturbesitz. p. 188.

- ↑ Verma, Archana (2007). Cultural and Visual Flux at Early Historical Bagh in Central India. Archana Verma. p. 1. ISBN 978-1407301518.

- ↑ Fowler 2005, p. 32.

- ↑ Beal 1883.

- ↑ Cowell 1894.

- ↑ Willemen 2009.

- ↑ Olivelle, Patrick (2008). Life of the Buddha by Ashva-ghosha (1st ed.). New York: New York University Press. p. xix. ISBN 978-0814762165.

- 1 2 Karetzky 2000, p. xxi.

- ↑ Beal 1875.

- ↑ Swearer 2004, p. 177.

- ↑ Schober 2002, p. 20.

- 1 2 Anålayo, "The Buddha and Omniscience", Indian International Journal of Buddhist Studies, 2006, vol. 7 pp. 1–20.

- ↑ Tan, Piya (trans) (2010). "The Discourse to Sandaka (trans. of Sandaka Sutta, Majjhima Nikāya 2, Majjhima Paṇṇāsaka 3, Paribbājaka Vagga 6)" (PDF). The Dharmafarers. The Minding Centre. pp. 17–18. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ MN 71 Tevijjavacchagotta [Tevijjavaccha]

- ↑ Access to Insight, ed. (2005). "A Sketch of the Buddha's Life: Readings from the Pali Canon". Access to Insight: Readings in Theravāda Buddhism. Access to Insight (Legacy Edition). Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ Jones 1956.

- ↑ Skilton 2004, pp. 64–65.

- ↑ Carrithers 2001, p. 15.

- ↑ Armstrong 2000, p. xii.

- ↑ Carrithers 2001.

- ↑ "Lumbini, the Birthplace of the Lord Buddha". World Heritage Convention. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ↑ Weise 2013.

- ↑ Trainor 2010, pp. 436–37.

- 1 2 Huntington 1988.

- 1 2 3 4 Samuel 2010.

- ↑ Hiltebeitel 2002.

- ↑ Beal 1875, p. 37.

- ↑ Jones 1952, p. 11.

- ↑ Beal 1875, p. 41.

- ↑ Turpie 2001, p. 3.

- 1 2 Narada 1992, pp. 9–12.

- ↑ Narada 1992, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Hamilton 2000, p. 47.

- ↑ Gombrich 1988, pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Thapar 2002, p. 146.

- 1 2 Narada 1992, p. 14.

- ↑ Mishra, Pankaj (2010). An End to Suffering: The Buddha in the World. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 153.

- ↑ Conze 1959, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Narada 1992, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Upadhyaya 1971, p. 95.

- ↑ Laumakis 2008, p. 8.

- ↑ Grubin 2010.

- ↑ Armstrong 2004, p. 77.

- ↑ Narada 1992, pp. 19–20.

- 1 2 3 "Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta: Setting the Wheel of Dhamma in Motion". Access to insight. 2012-02-12. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- 1 2 "The Golden Bowl". Buddha net. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- 1 2 Gyatso 2007, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ "The Basic Teaching of Buddha". SFSU. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 Anderson 1999.

- ↑ Williams 2002, pp. 74–75.

- ↑ Donald Lopez, Four Noble Truths, Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ Vetter 1988, pp. xxi–xxxvii.

- 1 2 Bronkhorst 1993, pp. 99–100, 102–11.

- ↑ "nirvana". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ↑ Malalasekera 1960, pp. 291–92.

- ↑ "Maha-parinibbana Sutta", Digha Nikaya (16), Access insight, verse 56

- ↑ Mettanando & Hinueber 2000.

- ↑ Mettanando (2001-05-15). "Buddha net". Archived from the original on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ↑ Waley 1932, pp. 343–54.

- ↑ Huntington 1986, p. 47.

- ↑ Von Hinüber 2009, p. 49.

- ↑ Kala 1724, p. 39.

- ↑ Eade 1995, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Katz 1982, p. 22.

- ↑ Lopez Jr., Donald S. "The Buddha's relics". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ Strong 2007, pp. 136–37.

- ↑ Asiatic Mythology by J. Hackin pp. 83ff

- ↑ Walshe 1995, pp. 441–60.

- ↑ Thera, Ven. Elgiriye Indaratana Maha (2002). "Vandana: The Album of Pali Devotional Chanting and Hymns" (PDF). Buddha net. pp. 49–52. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ↑ Epstein 2003, p. 200.

- ↑ Dhammananda, Ven. Dr. K. Sri, Great Virtues of the Buddha (PDF), Dhamma talks

- ↑ Shults 2014, p. 119.

- 1 2 Vetter 1988, p. ix.

- ↑ Warder 1999.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Bronkhorst 1993.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Vetter 1988.

- ↑ Schmithausen 1990.

- 1 2 3 4 Gombrich 1997.

- 1 2 3 Schmithausen 1981.

- ↑ Norman 1992.

- 1 2 Bronkhorst 1993, p. vii.

- 1 2 Warder 1999, p. inside flap.

- ↑ Davidson 2003, p. 147.

- ↑ Jong 1993, p. 25.

- ↑ Lopez 1995, p. 4.

- ↑ Vetter 1988, pp. xxx, xxxv–xxxvi, 4–5.

- ↑ Vetter 1988, p. 4.

- ↑ Vetter 1988, p. xxx.

- 1 2 Norman 1997, p. 29.

- ↑ Vetter 1988, pp. xxxiv–xxxvii.

- ↑ Gombrich 1997, p. 131.

- 1 2 Vetter 1988, p. 5.

- 1 2 Vetter 1988, p. xv.

- ↑ Vetter 1988, p. xxviii.

- 1 2 Bronkhorst 1993, p. 108.

- ↑ Bronkhorst 1993, p. 107.

- ↑ Norman 1997, p. 26.

- ↑ Norman 1997, p. 28.

- ↑ Gopal 1990, p. 73.

- ↑ "Buddha". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ↑ Sushil Mittal & Gene Thursby (2004), The Hindu World, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415772273, pp. 729–30

- ↑ C. Sharma (2013), A Critical Survey of Indian Philosophy, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120803657, p. 66

- ↑ Andrew J. Nicholson (2013), Unifying Hinduism: Philosophy and Identity in Indian Intellectual History, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0231149877, Chapter 9

- ↑ GS Ghurye, Indian Sociology Through Ghurye, a Dictionary, Ed. S. Devadas Pillai (2011), ISBN 978-8171548071, p. 354

- ↑ "Book One, Part V – The Buddha and His Predecessors".

- ↑ Tribe, Paul Williams with Anthony (2000). Buddhist thought a complete introduction to the Indian tradition. London: Taylor & Francis e-Library. pp. 1–10. ISBN 0203185935.

- ↑ Flood 1996, pp. 231–32.

- ↑ Islam and the Ahmadiyya Jamaʻat: History, Belief, Practice, p. 26, retrieved 15 November 2013 – via Google books

- ↑ Ousman Kobo (2012). Unveiling Modernity in Twentieth-Century West African Islamic Reforms. Brill Academic. p. 93. ISBN 978-9004233133.

- ↑ Donald Eugene Smith (2015). South Asian Politics and Religion. Princeton University Press. pp. 403–04. ISBN 978-1400879083.

- ↑ Twitchett 1986.

- ↑ Janet 2012, p. 3.

- ↑ Janet 2012, p. 9.

- ↑ Macdonnel 1900.

- ↑ Mershman 1913.

- ↑ Barnstone W & Meyer M (2009). The Gnostic Bible: Gnostic texts of mystical wisdom from the ancient and medieval worlds. Shambhala Publications: Boston & London.

- ↑ "info-sikh.com". www.info-sikh.com.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Carol (1999), Pain and Its Ending: The Four Noble Truths in the Theravada Buddhist Canon, Routledge

- Armstrong, Karen (2000), Buddha, Orion, ISBN 978-0753813409

- Asvaghosa (1883), The Fo-sho-hing-tsan-king, a life of Buddha, translated by Beal, Samuel, Oxford: Clarendon

- Bareau, André (1975), "Les récits canoniques des funérailles du Buddha et leurs anomalies: nouvel essai d'interprétation" [The canonical accounts of the Buddha's funerals and their anomalies: new interpretative essay], Bulletin de l'Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient (in French), Persée, LXII: 151–89, doi:10.3406/befeo.1975.3845

- ——— (1979), "La composition et les étapes de la formation progressive du Mahaparinirvanasutra ancien" [The composition and the etapes of the progressive formation of the ancient Mahaparinirvanasutra], Bulletin de l'Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient (in French), Persée, LXII: 45–103

- Baroni, Helen J. (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Zen Buddhism, Rosen

- The romantic legend of Sâkya Buddha (Abhiniṣkramaṇa Sūtra), translated by Beal, Samuel, London: Trübner, 1875

- Bechert, Heinz, ed. (1991–1997), The dating of the historical Buddha (Symposium), vol. 1–3, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht

- Bronkhorst, Johannes (1993), The Two Traditions of Meditation In Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass

- Buswell, Robert E, ed. (2003), Encyclopedia of Buddhism, 1, US: Macmillan Reference, ISBN 0028659104

- Carrithers, M. (2001), The Buddha: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0028659104

- Collins, Randall (2009), The Sociology of Philosophies, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0674029774 , 1120 pp.

- Conze, Edward, trans. (1959), Buddhist Scriptures, London: Penguin

- Cousins, LS (1996), "The dating of the historical Buddha: a review article", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 3, Indology, 6 (1): 57–63, doi:10.1017/s1356186300014760

- Cowell, Edward Byles, transl. (1894), "The Buddha-Karita of Ashvaghosa", in Müller, Max, Sacred Books of the East (PDF)

|format=requires|url=(help), XLIX, Oxford: Clarendon - Davidson, Ronald M. (2003), Indian Esoteric Buddhism, Columbia University Press, ISBN 0231126182

- Dhammika, S. (1993), The Edicts of King Asoka: An English Rendering, The Wheel Publication (386/387), Kandy, Sri Lanka: Buddhist Publication Society, ISBN 9552401046, archived from the original on 28 October 2013

- Dundas, Paul (2002), The Jains (Google Books) (2nd ed.), Routledge, p. 24, ISBN 978-0415266062, retrieved 25 December 2012

- Eade, JC (1995), The Calendrical Systems of Mainland South-East Asia (illustrated ed.), Brill, ISBN 978-9004104372

- Epstein, Ronald (2003), Buddhist Text Translation Society's Buddhism A to Z (illustrated ed.), Burlingame, CA: Buddhist Text Translation Society

- Fowler, Mark (2005), Zen Buddhism: beliefs and practices, Sussex Academic Press

- Gethin, Rupert, ML (1998), Foundations of Buddhism, Oxford University Press

- Gombrich, Richard F (1988), Theravada Buddhism: A Social History from Ancient Benares to Modern Colombo, Routledge and Kegan Paul

- ——— (1992), "Dating the Buddha: a red herring revealed", in Bechert, Heinz, Die Datierung des historischen Buddha [The Dating of the Historical Buddha], Symposien zur Buddhismusforschung (in German), IV (2), Gottingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, pp. 237–59 .

- ——— (1997), How Buddhism Began, Munshiram Manoharlal

- ——— (2000), "Discovering the Buddha's date", in Perera, Lakshman S, Buddhism for the New Millennium, London: World Buddhist Foundation, pp. 9–25 .

- Gopal, Madan (1990), K.S. Gautam, ed., India through the ages, Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, p. 73

- Grubin, David (Director), Gere, Richard (Narrator) (2010), The Buddha: The Story of Siddhartha (DVD), David Grubin Productions, 27:25 minutes in, ASIN B0033XUHAO

- Gyatso, Geshe Kelsang (2007), Introduction to Buddhism An Explanation of the Buddhist Way of Life, Tharpa, ISBN 978-0978906771

- Hamilton, Sue (2000), Early Buddhism: A New Approach: The I of the Beholder, Routledge

- Hartmann, Jens Uwe (1991), "Research on the date of the Buddha", in Bechert, Heinz, The Dating of the Historical Buddha (PDF), 1, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, pp. 38–39, archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-29

- Hiltebeitel, Alf (2002), "Hinduism", in Kitagawa, Joseph, The Religious Traditions of Asia: Religion, History, and Culture, Routledge

- Huntington, John C (1986), "Sowing the Seeds of the Lotus" (PDF), Orientations, September 1986: 46–58, archived from the original (PDF) on 28 November 2014

- Jain, Kailash Chand (1991), Lord Mahāvīra and His Times, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120808058

- Jayatilleke, K.N. (1963), Early Buddhist Theory of Knowledge (1st ed.), London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

- Jones, JJ (1949), The Mahāvastu, Sacred Books of the Buddhists, 1, London: Luzac & Co.

- ——— (1952), The Mahāvastu, Sacred Books of the Buddhists, 2, London: Luzac & Co.

- ——— (1956), The Mahāvastu, Sacred Books of the Buddhists, 3, London: Luzac & Co.

- Jong, JW de (1993), "The Beginnings of Buddhism", The Eastern Buddhist, 26 (2)

- Kala, U (2006) [1724], Maha Yazawin Gyi (in Burmese), 1 (4th ed.), Yangon: Ya-Pyei, p. 39

- Karetzky, Patricia (2000), Early Buddhist Narrative Art, Lanham, MD: University Press of America

- Katz, Nathan (1982), Buddhist Images of Human Perfection: The Arahant of the Sutta Piṭaka, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

- Keown, Damien; Prebish, Charles S (2013), Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Routledge

- Laumakis, Stephen (2008), An Introduction to Buddhist philosophy, Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521854139

- Lopez, Donald S (1995), Buddhism in Practice (PDF), Princeton University Press, ISBN 0691044422

- Malalasekera, G.P. (1960), Dictionary of Pali Proper Names, Vol. 1, London: Pali Text Society/Luzac

- Macdonnel, Arthur Anthony (1900), "

- Mahāpātra, Cakradhara (1977), The real birth place of Buddha, Grantha Mandir

- Mohāpātra, Gopinath (2000), "Two Birth Plates of Buddha" (PDF), Indologica Taurinensia, 26: 113–19, archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2012

- Mershman, Francis (1913), "Barlaam and Josaphat", in Herberman, Charles G; et al., The Catholic Encyclopedia, 2, New York: Robert Appleton

- Mettanando, Bhikkhu; Hinueber, Oskar von (2000), "The Cause of the Buddha's Death" (PDF), Journal of the Pali Text Society, XXVI: 105–18, archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2015

- Nakamura, Hajime (1980), Indian Buddhism: a survey with bibliographical notes, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120802728

- Narada (1992), A Manual of Buddhism, Buddha Educational Foundation, ISBN 9679920585

- Narain, A.K. (1993), "Book Review: Heinz Bechert (ed.), The dating of the Historical Buddha, part I", Journal of The International Association of Buddhist Studies, 16 (1): 187–201

- Norman, KR (1997), A Philological Approach to Buddhism (PDF)

|format=requires|url=(help), The Bukkyo Dendo Kyokai Lectures 1994, School of Oriental and African Studies (University of London) - Norman, K.R. (2003), "The Four Noble Truths", K.R. Norman Collected Papers II

- Prebish, Charles S. (2008), "Cooking the Buddhist Books: The Implications of the New Dating of the Buddha for the History of Early Indian Buddhism" (PDF), Journal of Buddhist Ethics, 15: 1–21, archived from the original (PDF) on 28 January 2012

- Rockhill, William Woodville, transl. (1884), The life of the Buddha and the early history of his order, derived from Tibetan works in the Bkah-Hgyur and Bstan-Hgyur, followed by notices on the early history of Tibet and Khoten, London: Trübner

- Roy, Ashim Kumar (1984), A history of the Jains, New Delhi: Gitanjali, p. 179

- Ruegg, Seyford (1999), "A new publication on the date and historiography of Buddha´s decease (nirvana): a review article", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 62 (1): 82–87, doi:10.1017/s0041977x00017572

- Samuel, Geoffrey (2010), The Origins of Yoga and Tantra. Indic Religions to the Thirteenth Century, Cambridge University Press

- Schmithausen, Lambert (1981), "On some Aspects of Descriptions or Theories of 'Liberating Insight' and 'Enlightenment' in Early Buddhism", in von Klaus, Bruhn; Wezler, Albrecht, Studien zum Jainismus und Buddhismus (Gedenkschrift für Ludwig Alsdorf) [Studies on Jainism and Buddhism (Schriftfest for Ludwig Alsdorf)] (in German), Wiesbaden, pp. 199–250

- Schober, Juliane (2002), Sacred biography in the Buddhist traditions of South and Southeast Asia, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

- Schumann, Hans Wolfgang (2003), The Historical Buddha: The Times, Life, and Teachings of the Founder of Buddhism, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 8120818172

- Shimoda, Masahiro (2002), "How has the Lotus Sutra Created Social Movements: The Relationship of the Lotus Sutra to the Mahāparinirvāṇa-sūtra", in Reeves, Gene, A Buddhist Kaleidoscope, Kosei

- Shults, Brett (2014), "On the Buddha's Use of Some Brahmanical Motifs in Pali Texts", Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies, 6: 106–40

- Srivastava, K.M. (1980), "Archaeological Excavations at Priprahwa and Ganwaria and the Identification of Kapilavastu", Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, 3 (1): 103–10

- Srivastava, K.M. (1979), "Kapilavastu and Its Precise Location", East and West, 29 (1/4): 61–74

- Skilton, Andrew (2004), A Concise History of Buddhism

- Smith, Peter (2000), "Manifestations of God", A concise encyclopaedia of the Bahá'í Faith, Oxford: Oneworld Publications, ISBN 1851681841 , 231 pp.

- Smith, Vincent (1924), The Early History of India (4th ed.), Oxford: Clarendon

- Strong, John S (2007), Relics of the Buddha, Motilal Banarsidass

- Swearer, Donald (2004), Becoming the Buddha, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press

- Thapar, Romila (2002), The Penguin History of Early India: From Origins to AD 1300, Penguin

- Trainor, Kevin (2010), "Kapilavastu", in: Keown, Damien; Prebish, Charles S. Encyclopedia of Buddhism, London: Routledge

- Tripathy, Ajit Kumar (Jan 2014), "The Real Birth Place of Buddha. Yesterday's Kapilavastu, Today's Kapileswar" (PDF), The Orissa historical research journal, Orissa State museum, 47 (1), archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-18

- Tuladhar, Swoyambhu D. (November 2002), "The Ancient City of Kapilvastu – Revisited" (PDF), Ancient Nepal (151): 1–7

- Turpie, D (2001), Wesak And The Re-Creation of Buddhist Tradition (PDF) (master's thesis), Montreal, QC: McGill University, archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-04-15

- Twitchett, Denis, ed. (1986), The Cambridge History of China, 1. The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BC – AD 220, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521243270

- Upadhyaya, KN (1971), Early Buddhism and the Bhagavadgita, Dehli: Motilal Banarsidass, p. 95, ISBN 978-8120808805

- Vetter, Tilmann (1988), The Ideas and Meditative Practices of Early Buddhism, Brill

- Von Hinüber, Oskar (2009), "Cremated like a King: The funeral of the Buddha within the ancient Indian context", Journal of the International College of Postgraduate Buddhist Studies, 13: 33–66

- Waley, Arthur (July 1932), "Did Buddha die of eating pork?: with a note on Buddha's image", Melanges Chinois et bouddhiques, NTU, 1931–32: 343–54, archived from the original on 3 June 2011

- Walshe, Maurice (1995), The Long Discourses of the Buddha. A Translation of the Digha Nikaya, Boston: Wisdom Publications

- Warder, Anthony K. (1998). "Lokayata, Ajivaka, and Ajnana Philosophy". A Course in Indian Philosophy (2nd ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. p. 45. ISBN 978-8120812444.

- Warder, AK (2000), Indian Buddhism, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

- Wayman, Alex (1997), Untying the Knots in Buddhism: Selected Essays, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 8120813219

- Weise, Kai; et al. (2013), The Sacred Garden of Lumbini – Perceptions of Buddha's Birthplace (PDF), Paris: UNESCO, archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-30

- Willemen, Charles, transl. (2009), Buddhacarita: In Praise of Buddha's Acts (PDF), Berkeley, CA: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research, ISBN 978-1886439429, archived from the original (PDF) on 27 August 2014

- Wynne, Alexander (2007), The Origin of Buddhist Meditation (PDF), Routledge, ISBN 0203963008

Further reading

The Buddha

- Bechert, Heinz, ed. (1996). When Did the Buddha Live? The Controversy on the Dating of the Historical Buddha. Delhi: Sri Satguru.

- Ñāṇamoli, Bhikku (1992). The Life of the Buddha According to the Pali Canon (3rd ed.). Kandy, Sri Lanka: Buddhist Publication Society.

- Wagle, Narendra K (1995). Society at the Time of the Buddha (2nd ed.). Popular Prakashan. ISBN 978-8171545537.