Quranism

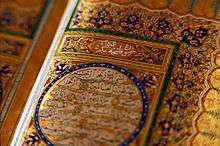

| Quran |

|---|

|

|

Quranism (Arabic: القرآنية; al-Qur'āniyya) describes any form of Islam that accepts the Quran as the only sacred text through which God (Allah) revealed himself to mankind, but rejects the religious authority, reliability, and/or authenticity of the Hadith collections.[1] Muslims that follow the Quran alone are called Quranians or Quranists or Quranites; they believe that God's message in the Quran is clear and complete as it is, and that it can therefore be fully understood without referencing the Hadith. Quranists affirm that the Hadith literature is apocryphal, as it had been written three centuries after the death of the Prophet Muhammad, thus it cannot have the same status as the Quran.

Quranism is similar to movements in Abrahamic religions such as the Karaite movement, Sadducees, and Essenes in Judaism and the Sola scriptura view of Protestant Christianity.[2] Hadith rejection has sometimes been associated with Muslim modernists.[3] In matters of faith and jurispudence, Qur'anists are pitted against ahl al-Hadith (which comprises of Sunnis, Shias and Ibadis), who first emerged two centuries after the death of the Prophet Muhammad as a movement of Hadith scholars who considered the Hadiths to be authority in matters of law and creed.

Terminology

Adherents of Quranism are referred to as Quranists (Arabic: قرآنيّون, Qurāniyyūn), or people of the Quran (Arabic: أهل القرآن, ’Ahl al-Qur’ān).[4] This should not be confused with Ahle-e-Quran, which is an organisation formed by Abdullah Chakralawi. Quranists may also refer to themselves simply as Muslims, Submitters, or reformists.[4]

Doctrine

تِلْكَ ءَايَٰتُ ٱللَّهِ نَتْلُوهَا عَلَيْكَ بِٱلْحَقِّ ۖ فَبِأَىِّ حَدِيثٍۭ |

These are the verses of Allah which We recite to you in truth. Then in what statement [Hadith] after (rejecting) Allah and His verses will they believe? |

| —Quran (Surah Al-Jathiya, 45:6) |

The extent to which Quranists reject the authenticity of the Sunnah varies,[5] but the more established groups have thoroughly criticised the authenticity of the Hadith and refused it for many reasons, the most prevalent being the Quranist say that Hadith is not mentioned in the Quran as a source of Islamic theology and practice, was not recorded in written form until more than two centuries after the death of Muhammad, and contain perceived internal errors and contradictions.[5][6]

Quranists believe that God's message in the Quran is clear and complete as it is, and that it can therefore be fully understood without referencing the Hadith.

Quranic verses (such as 24:54, 33:21) enjoin the believers to emulate Muhammad and obey his judgments, providing scriptural authority for following the Quran alone, since the example Muhammad left was to follow the Quran alone (as seen in 46:9, 7:203, 10:15). Quranists believe since Muhammad delivered and spoke the Quran, his judgement in his capacity as a messenger is the same as that of God. Quranists believe the Quran was written down in scriptural form during the time of the Prophet Muhammad.

History

The Quranist sentiment dates back to the time of the Prophet Muhammad.[7]:9 Since the Hadiths were not written until two centuries after the death of the Prophet Muhammad, Quranists believe the Quranic sentiment influenced the early Ummayad caliphate. According to Quranists, the caliphs of Islam who succeeded the Prophet Muhammad were Quranists, such as Abu Bakr, Umar ibn al-Khattab, Uthman ibn Affan, and Ali ibn Abi-Talib.

During the Abassid dynasty, the poet, theologian, and jurist, Ibrahim an-Nazzam founded a madhhab called the Nazzamiyya that rejected the authority of Hadiths and relied on the Quran alone.[8] His famous student, al-Jahiz, was also critical of those who followed Hadith, referring to his Hadithist opponents as al-nabita ("the contemptible").[9] A contemporary of an-Nazzam, al-Shafi'i, tried to refute the arguments of the Quranists and establish the authority of Hadiths in his book kitab jima'al-'ilm.[7]:19 And Ibn Qutaybah tried to refute an-Nazzam's arguments against Hadith in his book Ta'wil Mukhtalif al-Hadith.[10]

Despite the fall of the early Ummayad caliphate, according to historian Daniel W. Brown questioning the authenticity of the Hadith continued during the Abbasid dynasty and existed during the time of Al-Shafii when a group known as "Ahlul-Kalam", who argued that the Prophetic example of Muhammad "is found in following the Qur'an alone", rather than Hadith.[11][12] Daniel W. Brown describes Ahl al-Kalam as one three main groups in the time around the second century of Islam (Ahl ar-Ra'y and Ahl al-Hadith being the other two) clashing in polemical disputes over sources of authority in Islamic law. Ahl al-Kalam agreed with Ahl al-Hadith that the example of the Muhammad, the prophet of Islam, was authoritative, and it rejected the authority of Hadith on the grounds that its corpus contradicted the message of Muhammad and the Quran and was "filled with contradictory, blasphemous, and absurd" reports, and that in jurisprudence, even the smallest doubt about a source was too much. Thus, they believed, the legacy of the Prophet Muhammad was to be found in the Qur'an alone. Later, a similar group, the Mu'tazilites, also viewed the transmission of the Hadiths as not sufficiently reliable. The Hadith, according to them, was mere guesswork, conjecture, and innovation (bidah), while the Quran was complete and perfect, and did not require the Hadith or any other book to supplement or complement it.[13]

In South Asia during the 19th century, the Ahle Quran movement formed partially in reaction to the Ahle Hadith whom they considered to be placing too much emphasis on Hadith.[14] Many Ahle Quran adherents from South Asia were formerly adherents of Ahle Hadith but found themselves incapable of accepting certain hadiths.[14] In Egypt during the early 20th century, the ideas of Quranists like Muhammad Tawfiq Sidqi grew out of Salafism i.e. a rejection of taqlid.[14]

Organizations

Ahle Quran

Ahle Quran is an organisation formed by Abdullah Chakralawi, who described the Quran as "ahsan hadith", meaning most perfect hadith and consequently claimed it does not need any addition.[15] His movement relies entirely on the chapters and verses of the Quran. Chakralawi's position was that the Quran itself was the most perfect source of tradition and could be exclusively followed. According to Chakralawi, Muhammad could receive only one form of revelation (wahy), and that was the Quran. He argues that the Quran was the only record of divine wisdom, the only source of Muhammad's teachings, and that it superseded the entire corpus of hadith, which came later.[15]

Kala Kato

Kala Kato ("A mere man said it") is an Islamist Quranist group which has been based in northern Nigeria for decades.[16] It is a Qur'anic movement predominantly based in Niger and Nigeria.[17] The term translates as "a mere man said it" in the Hausa language (referring to the hadith attributed to Muhammad).[18] One of the most well-known Hadith rejecting leaders in Nigeria was Maitatsine and Musa Makaniki. Others include a scholar Malam Isiyaka Salisu.[19] Other notable Nigerian Hadith rejectors include High Court judge Isa Othman[20][21] and scholar Mallam Saleh Idris Bello.

Considering everyone not following their Qur'an alone beliefs heretical and infidels, Kala Kato's ideology has led to sectarian tensions and violence against Nigerian security forces, Sunnis and Shias.[22]

Malaysian Quranic Society

The Malaysian Quranic Society was founded by Kassim Ahmad. The movement holds several positions distinguishing it from Sunnis and Shias such as a rejection of the status of hair as being part of the awrah; therefore exhibiting a relaxation on the observance of the hijab.[23]

Quran Sunnat Society

The Quran Sunnat Society is a Quranist movement in India. The movement was behind the first ever woman to lead a Friday congregation prayer in the country of India. It also maintains an office and headquarters within Kerala.[24] There is a large community of Quranists in Kerala.[25]

Submitters

In the United States it was associated with Rashad Khalifa, founder of the United Submitters International. The group popularized the phrase: The Quran, the whole Quran, and nothing but the Quran.[6] After Khalifa declared himself the Messenger of the Covenant, he was rejected by other Muslim scholars as an apostate of Islam. Later, he was assassinated in 1990 by a terrorist group. Those interested in his work believe that there is a mathematical structure in the Quran, based on the number 19. A group of Submitters in Nigeria was popularised by high court judge Isa Othman.[26]

Notable Quranists

- Ahmed Subhy Mansour (born 1949), an Egyptian American Islamic scholar.[27] He founded a small group of Quranists, but was exiled from Egypt and is now living in the United States as a political refugee.[28]

- Chekannur Maulavi (born 1936; disappeared 29 July 1993), a progressive Islamic cleric who lived in Edappal in Malappuram district of Kerala, India. He was noted for his controversial and unconventional interpretation of Islam based on Quran alone. He disappeared on 29 July 1993 under mysterious circumstances and is now widely believed to be dead.[29]

- Edip Yüksel (born 1957), a Kurdish American philosopher, lawyer, Quranist advocate, author of Nineteen: God's Signature in Nature and Scripture, Manifesto for Islamic Reform and a co-author of Quran: A Reformist Translation. Currently teaches philosophy and logic at Pima Community College and medical ethics and criminal law courses at Brown Mackie College.[7][30]

- Muhammad Marwa (died 1980), better known as Maitatsine (Hausa for "the one who damns"), which refers to his curse-laden public speeches against the Nigerian state.[31] In December 1980, Yan Tatsine's Quranist militant jihadist rebellion against the Nigerian army and Sunnis and Shias led to to the deaths of around 5,000 people.[32]

- Musa Makaniki is a Nigerian Quranist. A close disciple of Maitatsine, he emerged as a leader and successor after his death.

- Rashad Khalifa (1935–1990), an Egyptian-American biochemist and Islamic reformer. In his book Quran, Hadith and Islam and his English translation of the Quran, Khalifa argued that the Quran alone is the sole source of Islamic belief and practice. He further declared that the Hadith and Sunna were 'Satanic inventions' under 'Satan's schemes'.[6] In the face of widespread anger and hostility by the Muslim world,[6] Khalifa was stabbed to death on 31 January 1990 by Glen Cusford Francis,[33] a member of the terrorist organization, Jamaat ul-Fuqra.

See also

References

- ↑ Ibrahim, Raymond (2016-08-12). "'Quranism' Claims ALL Islamic Violence and Intolerance Stems from Secondary Sources, NOT the Quran Itself". PJ Media. Retrieved 2018-06-25.

- ↑ Aziz Ahmad, Aziz (1967). Islamic Modernism in India and Pakistan 1857–1964. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Hanif, N. (1997). Islam and Modernity. Sarup & Sons. p. 72. ISBN 978-81-7625-002-3.

- 1 2 Haddad, Yvonne Y.; Smith, Jane I. (3 November 2014). The Oxford Handbook of American Islam. Oxford University Press. pp. 150–153. ISBN 978-0-19-986264-1.

- 1 2 Voss, Richard Stephen (April 1996). "Identifying Assumptions in the Hadith/Sunnah Debate". Monthly Bulletin of the International Community of Submitters. 12 (4). Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Musa, Aisha Y. (2010). "The Qur'anists". Religion Compass. John Wiley & Sons. 4 (1): 12–21. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8171.2009.00189.x. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 Musa, Aisha Y. (2008). Hadith as Scripture: Discussions on The Authority Of Prophetic Traditions in Islam. Palgrave. ISBN 978-0-230-60535-0.

- ↑ Abdul-Raof, Hussein (2012). Theological Approaches to Quranic Exegesis: A Practical Comparative-Contrastive Analysis. London: Routledge. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-0-41544-958-8.

- ↑ Zaman, Muhammad Qasim (1997). Religion and Politics Under the Early 'Abbasids: The Emergence of the Proto-Sunni Elite. Leiden: E.J. Brill. p. 55. ISBN 978-9-00410-678-9.

- ↑ Juynboll, G. H. A. (1969). The Authenticity of the Tradition Literature: Discussions in Modern Egypt. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 77–80.

- ↑ Brown, Rethinking tradition in modern Islamic thought, 1996: p.15-16

- ↑ excerpted from Abdur Rab, ibid, pp. 199–200.

- ↑ Azami, M. A., Studies in Hadith Methodology and Literature, Islamic Book Trust, Kuala Lumpur, 92; cited in Akbarally Meherally, Myths and Realities of Hadith – A Critical Study, (published by Mostmerciful.com Publishers), Burnaby, BC, Canada, 6; available at http://www.mostmerciful.com/Hadithbook-sectionone.htm; excerpted from Abdur Rab, ibid, p. 200.

- 1 2 3 Brown, Daniel W. (1996). Rethinking Tradition in Modern Islamic Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 38–41. ISBN 978-0-52157-077-0.

- 1 2 Aḥmad (1967), pp.120-121.

- ↑ [http://www.rfi.fr/actuen/articles/120/article_6332.asp.

- ↑ Islamic actors and interfaith relations in northern Nigeria (PDF) (Report). Nigeria Research Network. March 2013. p. 8. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ↑ Diversity in Nigerian Islam retrieved 8 June 2013

- ↑ Abiodun Alao, Islamic Radicalisation and Violence in Nigeria, accessed March 1, 2013

- ↑ Philip Ostien, A Survey of the Muslims of Nigeria's North Central Geo-political Zone, Nigeria Research Network, accessed March 1, 2013.

- ↑ Muhammad Nur Alkali, Abubakar Kawu Monguno, Bellama Shettima Mustafa, Overview Of Islamic Actors In Northeastern Nigeria, Nigeria Research Network, accessed March 1, 2013.

- ↑ McGregor, Andrew (24 July 2010). "Nigeria's Imams Warn of Threat from Kala Kato Islamist Movement".

- ↑ "Malay intellectual Kassim Ahmad dies". The Malaysian Insight. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ↑ Dhillon, Amrit (30 January 2018). "Muslim woman receives death threats after leading prayers in Kerala". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ↑ Khan, Aftab Ahmad (2016). "Islamic Culture and the Modern World 2". Defence Journal. 20 (4): 49.

- ↑ Muhammad Nur Alkali; Abubakar Kawu Monguno; Ballama Shettima Mustafa (January 2012). Overview of Islamic actors in northern Nigeria (PDF) (Report). Nigeria Research Network. p. 16. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ↑ "About Us". Ahl-alquran.com. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- ↑ Oldenburg, Don (13 May 2005). "Muslims' Unheralded Messenger". The Washington Post. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- ↑ Kumar, Girja (1997). The Book on Trial: Fundamentalism and Censorship in India. New Delhi: Har Anand Publications. pp. 34–35. ISBN 978-8-12410-525-2.

- ↑ Kenney, Jeffrey T.; Moosa, Ebrahim (2013). Islam in the Modern World. Routledge. p. 21.

- ↑ Diversity in Nigerian Islam retrieved 8 June 2013

- ↑ Glassé, Cyril, ed. (2003). The New Encyclopedia of Islam. Rowman Altamira. p. 481. ISBN 978-0-7591-0190-6.

- ↑ "State of Arizona v. Francis, Glen Cusford". The Investigative Project on Terrorism. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

Further reading

- Aisha Y. Musa, Hadith as Scripture: Discussions on the Authority of Prophetic Traditions in Islam, New York: Palgrave, 2008. ISBN 0-230-60535-4.

- Ali Usman Qasmi, Questioning the Authority of the Past: The Ahl al-Qur'an Movements in the Punjab, Oxford University Press, 2012. ISBN 0-195-47348-5.

- Daniel Brown, Rethinking Tradition in Modern Islamic Thought, Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-521-65394-0.