Mahavira

| Mahavira | |

|---|---|

| 24th Jain Tirthankara | |

Statue of Mahavira at Shri Mahavirji, Rajasthan | |

| Other names | Vīr, Ativīr, Vardhamāna, Sanmati, Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta |

| Venerated in | Jainism |

| Predecessor | Parshvanatha |

| Symbol | Lion[1] |

| Height | 7 cubits (10.5 feet) (traditional) |

| Age | 72 years |

| Tree | Shala |

| Complexion | Golden |

| Personal information | |

| Born |

c. 497 BCE (historical)[2][3] c. 599 BCE (traditional)[2] Kundagrama, Vaishali, Vajji (present-day Vaishali district, Bihar, India) |

| Died |

c. 425 BCE (historical)[2][3] c. 527 BCE (Svetambara)[2] c. 510 BCE (Digambara)[2] Pawapuri, Magadha (present-day Bihar, India) |

| Parents |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

|

Jain prayers |

|

Ethics |

|

Major sects |

|

Festivals |

|

|

Mahavira (IAST: Mahāvīra, /məˌhɑːˈvɪərə/;[4]), also known as Vardhamāna, was the twenty-fourth Tirthankara (ford-maker) of Jainism. In the Jain tradition, it is believed that Mahavira was born in the early part of the 6th century BC into a royal kshatriya family in what is now Bihar, India. At the age of thirty, abandoning all worldly possessions, he left his home in pursuit of spiritual awakening and became an ascetic. For the next twelve and a half years, Mahavira practiced intense meditation and severe austerities, after which he is believed to have attained Kevala Jnana (omniscience). He preached for thirty years, and is believed by Jains to have died in the 6th century BC, though the year he is believed to have died varies by the Jain sect.[5][2] Scholars such as Karl Potter consider his biographical details as uncertain,[6] with some suggesting he lived in the 5th century BC contemporaneously with the Buddha.[2][3] Mahavira died at the age of 72, and his remains were cremated.[7][8]

After he gained Kevala Jnana, Mahavira taught that the observance of the vows ahimsa (non-violence), satya (truth), asteya (non-stealing), brahmacharya (chastity), and aparigraha (non-attachment) is necessary to spiritual liberation. He gave the principle of Anekantavada (many-sided reality),[9] Syadvada and Nayavada. The teachings of Mahavira were compiled by Gautama Swami (his chief disciple) and were called Jain Agamas. These texts were transmitted through oral tradition by Jain monks, but are believed to have been largely lost by about the 1st century when they were first written down. The surviving versions of the Agamas taught by Mahavira are some of the foundational texts of Jainism.

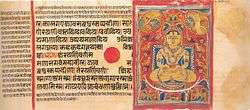

Mahavira is usually depicted in a sitting or standing meditative posture with the symbol of a lion beneath him.[10] The earliest iconography for Mahavira is from archaeological sites in the north Indian city of Mathura.[11][12] These are variously dated from the 1st century BC to the 2nd century AD. The day he was born is celebrated as Mahavir Janma-kalyanak (popularly known as Mahavir Jayanti), and the day of his death is observed by Jains as Diwali.[13]

Titles and names

The early Jain and Buddhist literature that has survived into the modern era uses other names or epithets for Mahavira. These include Nayaputta, Muni, Samana, Niggantha, Bramhan, and Bhagavan.[14] In early Buddhist Suttas, he is also referred to by the names Araha (meaning "worthy"), and Veyavi (derived from the word "Vedas", but contextually it means "wise" because Mahavira did not recognize the Vedas as a scripture).[15] Buddhist texts refer to Mahavira as Nigaṇṭha Jñātaputta.[16] Nigaṇṭha means "without knot, tie, or string" and Jñātaputta (son or scion of Natas), refers to his clan of origin as Jñāta or Naya (Prakrit).[17][18][19] The Jain text Kalpasutras states that he is also known as Sramana because he is "devoid of love and hate".[20]

According to later Jain texts, Mahavira's childhood name was Vardhamāna ("the one who grows"), because of the increased prosperity in the kingdom at the time of his birth.[21] According to the Kalpasutras, he was called Mahavira ("the great hero") by the gods because he stood steadfast in the midst of dangers and fears, hardships and calamities.[20] Mahavira is also called a Tirthankara.[17]

Historical Mahavira

.png)

Though it is universally accepted by scholars of Jainism that Mahavira was an actual person who lived in ancient India, the details of his biography and the year of his birth are uncertain,[6] and continue to be a subject of considerable debate among scholars.[22] Digambara text, Uttarapurāna mention that Mahavira was born at Kundpur kingdom of Videh.[23] and Svetambara text, Kalpasūtra use the name Kundagrama.[14][24] It is said to be located in present-day Bihar, India. This is assumed to be the modern town of Basu Kund, which is about 60 kilometres (37 miles) north of Patna, the capital of Bihar.[25][3] However, it is unclear if the ancient Kundagrama is the same as the current assumed location, and the birthplace remains a subject of dispute.[6][14][26] Mahavira renounced all his material wealth and left his home when he was twenty-eight by some accounts,[5] or thirty by others,[27] then lived an ascetic life and performed severe austerities for twelve years, and thereafter preached Jainism for a period of thirty years.[5] The location where he preached has been a subject of historic disagreement between the two major sub-traditions of Jainism – the Svetambaras and the Digambaras.[14]

The Jain Śvētāmbara tradition believes he was born in 599 BC and died in 527 BC, while the Digambara tradition believes 510 BC was the year he died.[5][2] The scholarly controversy arises from efforts to date him and the Buddha, because both are believed to be contemporaries according to Buddhist and Jain texts, and because, unlike for Jain literature, there is extensive ancient Buddhist literature that has survived.[2] Almost all Indologists and historians, state Dundas and others, accordingly date Mahavira's birth to about 497 BC and his death to about 425 BC.[2][3] However, the Vira era tradition that started in 527 BC and places Mahavira in the 6th century BC is a firmly established part of the Jain community tradition.[2]

The 12th-century Jain scholar Hemachandra placed Mahavira in the 5th century BC.[28][29] According to Kailash Jain, Hemachandra made an incorrect analysis that, along with attempts to establish Buddha's nirvana date, has been a source of confusion and controversy about Mahavira's year of nirvana.[30] Kailash Jain states the traditional date of 527 BC is accurate, adding that the Buddha was a junior contemporary of the Mahavira and that the Buddha "might have attained nirvana a few years later".[31] The place of his death, Pavapuri (now in Bihar), is a pilgrimage site for Jains.[5]

Biography per Jain traditions

According to Jain texts, 24 Tirthankaras have appeared on earth in the current time cycle of Jain cosmology. Mahavira was the last Tirthankara of Avasarpiṇī (present descending phase or half of the time cycle).[note 1][33] A Tirthankara (Maker of the River-Crossing, saviour, spiritual teacher) signifies the founder of a tirtha, which means a fordable passage across the sea of interminable cycles of births and deaths (called saṃsāra).[34][35][36]

Birth

Belonging to Kashyapa gotra,[20][25] Mahavira was born into the royal Kshatriya family of King Siddhartha and Queen Trishala of the Ikshvaku dynasty.[37][note 2] This is the same solar dynasty in which Hindu epics place Rama and the Ramayana,[38] and in which the Buddhist texts place the Buddha,[39] and the Jains attribute another twenty-one of their twenty-four Tirthankaras over millions of years.[40][41]

According to the Digambara Jains, Mahavira was born in 540 BC.[42] According to the Svetambara Jain texts, he was born in 599 BC. Mahavira's birthday, in the traditional calendar, falls on the thirteenth day of the rising moon in the month of Chaitra in the Vira Nirvana Samvat calendar.[5][43][44] In the Gregorian calendar, this date falls in March or April and is celebrated by Jains as Mahavir Jayanti.[45]

Kundagrama, the site of Mahavira’s birth is believed by tradition to be near Vaishali, a great ancient town in the Gangetic plains. The identity of this place in the modern geography of Bihar is unclear, in part because people migrated out of ancient Bihar for economic and political reasons.[14] Dundas states that, according to the "Universal History" in Jain mythology, Mahavira had undergone many rebirths before his birth in the 6th century. These rebirths included being a hell-being, a lion, and a god (deva) in a heavenly realm in Jain cosmology just before his last birth as the 24th fordmaker.[46] According to the texts of Svetambara sect, his embryo was first formed in a Brahman woman, but his embryo was then transferred by the divine commander of Indra's army, Hari-Naigamesin, to the womb of Trishala, the wife of Siddhartha.[47][48][note 3] The embryo transfer legend is not accepted by the adherents of the Digambara tradition.[50][7]

Jain texts state that, after Mahavira was born, the god Indra came from the heavens, anointed him, and performed his abhisheka (consecration) on Mount Meru.[46] These events are illustrated in the artwork of numerous Jain temples and play a part in modern Jain temple rituals.[51] The Kalpa sutras describing Mahavira's birth legends are recited by the Svetambara Jains during annual festivals such as Paryushana, but the same festival is observed by the Digambaras without the recitation.[52]

Early life

Mahavira grew up as a prince. According to the second chapter of the Śvētāmbara text Acharanga Sutra, both of his parents were followers and lay devotees of Parshvanatha.[53][21] Jain traditions do not agree on whether Mahavira ever married.[7][54] According to the Digambara tradition, Mahavira's parents wanted him to marry Yashoda but Mahavira refused to marry.[55][note 4] According to the Śvētāmbara tradition, he was married to Yashoda at a young age and had one daughter, Priyadarshana,[46][25] also called Anojja.[57]

Jain texts portray Mahavira as a very tall man, with his height stated to be seven cubits (10.5 feet) in Aupapatika Sutra.[58] In Jain mythology, he was the shortest of the 24 Tirthankaras, with earlier teachers believed to have been much taller, with the 22nd Tirthankara Aristanemi, who lived for 1,000 years, stated to have been forty cubits tall (60 feet).[59]

Renunciation

At the age of thirty, Mahavira abandoned the comforts of royal life and left his home and family to live an ascetic life in the pursuit of spiritual awakening.[32][60][61] He undertook severe austerities of fasting and bodily mortifications,[62] meditated under the Ashoka tree, and discarded his clothes.[32][63] There is a graphic description of his hardships and humiliation in the Acharanga Sutra.[64][65] According to the Kalpa Sūtra, Mahavira spent the first forty-two monsoons of his life at Astikagrama, Champapuri, Prstichampa, Vaishali, Vanijagrama, Nalanda, Mithila, Bhadrika, Alabhika, Panitabhumi, Shravasti, and Pawapuri.[66] He is said to have lived in Rajagriha during the rainy season of the forty-first year of his ascetic life. This is traditionally dated to have been in 491 BC.[67]

Omniscience

After twelve years of rigorous penance, at the age of forty-three Mahavira achieved the state of Kevala Jnana (omniscience or infinite knowledge) under a Sāla tree, according to traditional accounts.[60][68][69] The details of this event are mentioned in Jain texts such as Uttar-purāņa and Harivamśa-purāņa.[70] The Acharanga Sutra describes Mahavira as all-seeing. The Sutrakritanga elaborates the concept as all-knowing and provides details of other qualities of Mahavira.[14] Jains believe that Mahavira had the most auspicious body (paramaudārika śarīra) and was free from eighteen imperfections when he attained omniscience.[71] The Śvētāmbara believe that Mahavira traveled throughout India to teach his philosophy for thirty years after gaining omniscience.[60] The Digambara, however, claim that after attaining omniscience, he sat fixed in his Samavasarana, giving sermons to his followers.[72]

Disciples

The Jain texts state that Mahavira's first disciples were eleven Brahmins who are traditionally called the eleven Ganadharas.[42] Gautama was their chief.[72] Others were Agnibhuti, Vayubhuti, Akampita, Arya Vyakta, Sudharman, Manditaputra, Mauryaputra, Acalabhraataa, Metraya, and Prabhasa. Mahavira's disciples are said to be led by Gautama after him, who later is said to have made Sudharman his successor.[60] These eleven Brahmin–Ganadharas, as the early followers, were responsible for remembering and verbally transmitting the teachings of the Mahavira after his death, which came to be known as Gani-Pidaga or Jain Agamas.[73]

According to the Jain tradition, Mahavira had 14,000 muni (male ascetics), 36,000 aryika (nuns), 159,000 sravakas (laymen), and 318,000 sravikas (laywomen) as his followers.[74][75][76] Some of the royal followers included King Srenika (popularly known as Bimbisara) of Magadha, Kunika of Anga, and Chetaka of Videha.[66][77] Mahavira initiated the mendicants with the Mahavratas (Five vows).[42] He delivered fifty-five pravachana and answered thirty-six unasked questions (Uttaraadhyayana-sutra).[60]

Nirvāṇa, Moksha

.jpg)

Jains believe Mahavira attained omniscience at the age of 42, under a Sala tree on the banks of River Rijupalika near Jrimbhikagrama.[78] He preached, then died at the age of 72. The Jain Śvētāmbara tradition believes his death occurred in 527 BC, while the Digambara Jain tradition believes this happened in 510 BC.[2] His jiva (soul) is believed in all Jain traditions to be in Siddhashila (abode of the liberated souls).[79]

According to Jain texts, Mahavira's nirvana[note 5] (death) occurred in the town of Pawapuri (Bihar).[81][82][13] His life as a spiritual light and the night of his nirvana is remembered by Jains as Diwali on the same night that Hindus celebrate their festival of lights.[13][79] On the night that Mahavira died, his chief disciple Gautama is said to have attained omniscience.[76]

The accounts of Mahavira's death vary among the Jain texts, some describing a simple death but others describing grandiose celebrations attended by gods and kings. According to the Jinasena's Mahapurana, the heavenly beings arrived to perform his funeral rites. According to the Pravachanasara, only the nails and hair of Tirthankaras are left behind; the rest of the body is dissolved in the air like camphor.[83] In some texts he is described, at age 72, to be giving his final preaching over six days to a large crowd of people. Everyone falls asleep, only to awaken to find that he has disappeared, leaving only his nails and hair, which his followers cremate.[84]

Today, a Jain temple called Jal Mandir stands at the place of Mahavira's nirvana (moksha).[85] Jain artwork in temples and texts depicts the final liberation and cremation of Mahavira, sometimes symbolically shown as a miniature pyre of sandalwood and a piece of burning camphor.[86]

Previous births

Mahavira's previous births are discussed in Jain texts such as the Mahapurana and Tri-shashti-shalaka-purusha-charitra. While a soul undergoes countless reincarnations in the transmigratory cycle of saṃsāra (world), the births of a Tirthankara are reckoned from the time he determined the causes of karma and developed the Ratnatraya. Jain texts discuss 26 births of Mahavira before his incarnation as a Tirthankara.[66] According to the texts, Mahavira was born as Marichi, the son of Bharata Chakravartin, in one of his previous births.[46]

Sources

- Tiloya-paṇṇatti of Yativṛṣabha discusses almost all of the events connected with the life of Mahavira in a form convenient to memorisation.[87]

- Acharya Jinasena's Mahapurāṇa include Ādi purāṇa and Uttara-purāṇa. It was completed by his disciple Acharya Gunabhadra in the 8th century. In the Uttara-purāṇa the life of Mahavira is described in three parvans (74–76) in 1,818 verses.[88]

- Vardhamacharitra is a Sanskrit kāvya (poem) describing the life of Mahavira written by Asaga in 853.[89][90][91]

- Kalpa Sūtra is a collection of biographies of the Jain Tirthankaras, notably Parshvanatha and Mahavira.

- Samavayanga Sutra is a collection of texts containing Lord Mahavira’s teachings.

- Acharanga Sutra describes the penance of Mahavira.

Teachings

Colonial-era Indologists, considered Jainism and Mahavira's followers to be a sect of Buddhism because of the superficial similarities in their iconography, meditative and ascetic practices.[16] However, as studies and understanding progressed, the differences between the teachings of the Mahavira and the Buddha were found to be so markedly divergent that the two gained recognition as separate religions.[92] Mahavira, states Moriz Winternitz, taught a "very elaborate belief in the soul" unlike the Buddhists who denied it, the ascetic practices in his teachings have been of a higher order of magnitude than those found in either Buddhism or Hinduism, and his emphasis on Ahimsa (non-violence) against all life forms is far greater than in all other Indian religions.[92]

Jain Agamas

Mahavira's teachings were compiled by his Ganadhara (chief disciple), Gautama Swami.[93] The sacred canonical scriptures comprised twelve parts.[94] The Mahavira's teachings were gradually lost after around 300 BC, according to the Jain tradition, when a severe famine in the Magadha region of ancient India caused a scattering of the Jain monks. Thereafter, attempts were made by Jain monks to gather again, co-recite the canon, and re-establish it in its entirety.[95] These efforts identified differences between recitations of the Mahavira's teachings, and an attempt was made in the 5th century AD to reconcile the differences.[95] However, the reconciliation efforts failed, with Svetambara and Digambara Jain traditions continuing with their own incomplete, somewhat different versions of the Mahavira's teachings. In the early centuries of the common era, Jain texts containing Mahavira's teachings were written down in palm leaf manuscripts.[73] According to the Digambaras, Āchārya Bhutabali was the last ascetic who had partial knowledge of the original canon. Later, some learned Āchāryas restored, compiled, and wrote down the teachings of Mahavira that were the subject matter of the Agamas.[96] Āchārya Dharasena, in the 1st century CE, guided Āchārya Pushpadant and Āchārya Bhutabali as they wrote down these teachings. The two Āchāryas wrote on palm leaves, Ṣaṭkhaṅḍāgama – among the oldest known Digambara Jain texts.

Five vows

Jain Agamas prescribe five major vratas (vows) that both ascetics and householders have to follow.[97] These ethical principles were preached by Mahavira:[60][98]

- Ahimsa (Non-violence or Non-injury). Mahavira taught that every living being has sanctity and dignity of its own and it should be respected just as one expects one's own sanctity and dignity to be respected. Ahimsa is formalised into Jain doctrine as the first and foremost vow. The concept applies to action, speech, and thought.[99]

- Satya (Truthfulness) – Neither lie, nor speak what is not true, do not encourage others or approve anyone who speaks the untruth.[99]

- Asteya (Non-stealing) – Theft is explained as "taking anything that has not been given".[100]

- Brahmacharya (Chastity) – Abstinence from sex and sensual pleasures for Jain monks, faithfulness to one's partner for Jain householders.[99][101]

- Aparigraha (Non-attachment) – For laypersons, the attitude of non-attachment to property or worldly possessions; for mendicants, not owning anything.[102]

The goal of these principles is to achieve spiritual peace, better rebirth, or, ultimately, liberation.[103][104][105] According to Chakravarthi, these teachings help elevate a person's quality of life.[106] In contrast, states Dundas, the emphasis of Mahavira on non-violence and restraint has been interpreted by some Jain scholars to "not be driven by merit from giving or compassion to other creatures, nor a duty to rescue all creatures", but resulting from "continual self discipline", a cleansing of the soul that leads to one's own spiritual development and ultimately brings about spiritual release.[107]

Of these precepts, Mahavira is most remembered in the Indian traditions for his teachings of ahimsa (non-injury) as the supreme ethical and moral virtue.[60][108] Mahavira taught that the doctrine of non-injury must cover all living beings,[109] and causing injury to any being in any form creates bad karma which affects one's rebirth and future well-being and suffering.[110] According to Mahatma Gandhi, Mahāvīra was the greatest authority on Ahimsa.[111][112][113]

Soul

Mahavira taught that the soul exists, a premise that Jainism shares with Hinduism but not Buddhism. According to Buddhism, there is no soul or self, and its teachings are based on the concept of anatta.[114][115][116] In contrast, Mahavira taught that the soul is permanent and eternal with respect to dravya (substance).[117] Mahavira additionally taught that the soul is also impermanent with respect to paryaya (modes that originate and vanish).[117]

To Mahavira, the metaphysical nature of the universe consists of dravya, jiva, and ajiva.[77] The jiva gets attached and bound to samsara (worldly realms of suffering and existence) because of karma (activity).[77] Karma, in Jainism, includes both actions and intent, and it colors (lesya) the soul; its particles stick to the soul and affect how, where, and what the soul is instantaneously reborn into after a being dies.[118]

There is no creator God, according to Mahavira's teachings, and existence has neither beginning nor end. However, there are gods and demons in Jain beliefs, whose jivas are a part of the same cycles of births and deaths depending on the accumulated karmic particles.[119] The goal of spiritual practice is to liberate the jiva from all karmic accumulation, and thus enter the realm of the siddhas who are never reborn again.[120] Enlightenment, to Mahavira, is the consequence of a process of self-cultivation and self-restraint.[107]

Anekantavada

Mahavira taught the doctrine of "many-sided reality". This doctrine is now known as Anekantavada or Anekantatva.[121][122] This term does not appear in the earliest layer of Jain literature or the Jain Agamas, but the doctrine is illustrated in the answers of Mahavira to questions his followers asked.[121] According to Mahavira, truth and reality are complex and always have multiple aspects. Reality can be experienced, but it is not possible to express it completely with language. Human attempts to communicate are Naya, or a "partial expression of the truth".[121] Language is not Truth, but a means and attempt to express Truth. From Truth, according to Mahavira, language returns and not the other way around.[121][123] One can experience the truth of a taste, but cannot fully express that taste through language. Any attempt to express the experience is syāt, or valid "in some respect" but still remaining a "perhaps, just one perspective, incomplete".[123] In the same way, spiritual truths are complex, with multiple aspects, and language cannot express their plurality, yet through effort and appropriate karma they can be experienced.[121]

The Anekantavada premises of Mahavira are also summarized in Buddhist texts such as the Samaññaphala Sutta, wherein he is called Nigantha Nataputta.[note 6] The Anekantavada doctrine is another key difference between the teachings of the Mahavira and those of the Buddha. The Buddha taught the Middle Way, rejecting, in answer to questions, extremes of the answer "it is" or "it is not". The Mahavira, in contrast, accepted both "it is" and "it is not", with the qualification of "perhaps" and with reconciliation.[125]

The Jain Agamas suggest that Mahavira's approach to answering all metaphysical philosophical questions was a "qualified yes" (syāt). A version of this doctrine is also found in the Ajivika tradition of ancient Indian philosophies.[126][127]

In contemporary times, according to Dundas, the Anekantavada doctrine has been interpreted by many Jains as intending to "promote a universal religious tolerance", and a teaching of "plurality" and "benign attitude to other [ethical, religious] positions", but this is problematic and a misreading of Jain historical texts and Mahavira's teachings.[128] The "many pointedness, multiple perspective" teachings of the Mahavira is a doctrine about the nature of reality and human existence, and it was not a doctrine about tolerating religious positions such as on sacrificing or killing animals for food, violence against disbelievers or any other living being as "perhaps right".[128] The five vows for Jain monks and nuns, for example, are strict requirements, and there is no "perhaps".[129] Beyond the renunciant Jain communities, while Mahavira's Jainism co-existed with Buddhism and Hinduism through history, according to Dundas, each were also "highly critical of the knowledge systems and ideologies of their rivals".[130]

Gender

One of the historically contentious views within Jainism is in part attributed to Mahavira and his ascetic life where he never wore any clothes as a mark of disowning everything (interpreted as a consequence of the fifth vow of Aparigraha). The disputes triggered by this teaching of Mahavira are those related to gender and whether a female mendicant (sadhvi) can achieve spiritual liberation just like a male mendicant (sadhu) through Jain ascetic practices.[131][132]

The main sub-traditions of Jainism have historically disagreed, with Digambaras (sky-clad, naked mendicant order) stating that a woman is by her nature and her body unable to practice asceticism, such as by living naked, and therefore she cannot achieve spiritual liberation because of her gender. She can at best, state the Digambara texts, live an ethical life so that she is reborn as a man in a future life.[note 7] In this view, she is also viewed a threat to a monk's chastity.[134] In contrast, Svetambaras (white-clad, wear clothes) have interpreted Mahavira's teaching as encouraging both males and females to pursue a mendicant ascetic life with the possibility of moksha (kaivalya, spiritual liberation) regardless of gender.[134][132][135]

Rebirth and realms of existence

Rebirth and realms of existence are foundational teachings of Mahavira. According to the Acaranga Sutra, Mahavira comprehended life to exist in myriad forms, such as animals, plants, insects, water bodies, fire bodies, wind bodies, elemental forms, and others.[110][136] He taught that a monk should avoid touching or disturbing any one of them including plants, never swim in water, nor light a fire or extinguish it, nor thrash their arms in the air as such actions can torment or hurt other beings that live in those states of matter.[110]

Mahavira preached that the nature of existence is cyclic, where the jiva (soul) of beings is reborn after death in one of the triloka – heavenly, hellish, or earthly realms of existence and suffering.[137] According to Mahavira, human beings are reborn, depending on one's karma (actions) as a human, animal, element, microbe, and other forms, on earth or in a heavenly or hellish state of existence.[110][138][139] Nothing is permanent, everyone, including gods, demons and beings on the earthly realms, die and are reborn again based on their karma merits and demerits. It is the Jina who have reached Kevala Jnana who are not reborn again,[110] and attain the siddhaloka or the "Realm of the Perfected Ones".[138]

Legacy

Ascetic lineage

Mahavira has been mistakenly called the founder of Jainism.[140] Jains believe that there were 23 teachers before the Mahavira, and they believe that Jainism was founded in far more ancient times than that of the Mahavira, whom they revere as the 24th Tirthankara.[62] The first 22 Tirthankaras are placed in mythical times. For example, the 22nd Tirthankara Neminath is believed in the Jain tradition to have been born 84,000 years before the 23rd Tirthankara named Parshvanatha.[141] Mahavira is sometimes placed within Parshvanatha lineage, but this is contradicted by all Jain texts, which state that Mahavira renounced the world alone.[11]

Jain texts suggest that Mahavira's parents were lay devotees and followers of Parshvanatha. However, the lack of details and mythical nature of the legends about Parshvanatha,[142][143] combined with medieval-era Svetambara texts portraying Parsvites as "pseudo-ascetics" with "dubious practices of magic and astrology" have led scholars to debate the evidence for Parshvanatha's historicity.[11] Regardless of scholarly speculations, according to Dundas Jains believe that Parshvanatha lineage influenced Mahavira. Parshvanatha, as the one who "removes obstacles and has the capacity to save", has been a highly popular icon and his image the greatest focus of Jain devotional activity in temples.[11] Of the 24 Tirthankaras, the Jain iconography has celebrated Mahavira and Parshvanatha the most since the earliest times, with sculptures discovered at the Mathura archaeological site that have been dated to the 1st century BCE by modern dating methods.[11][12][144]

According to Moriz Winternitz, Mahavira may be considered as a reformer of a pre-existing sect of Jains called Niganthas (fetter-less) that is mentioned in early Buddhist texts.[16]

Festivals

The two major annual festivals in Jainism associated with Mahavira are Mahavir-Jayanti and Diwali. During Mahavir Jayanti , Jains celebrate the birth of Mahavira, 24th and last Tirthankara (Teaching God) of Avasarpiṇī.[45] In Mahavir Jayanti, the five auspicious events (Kalyaans) of Mahavira's life are re-enacted.[145] Diwali marks the anniversary of Nirvana or the liberation of Mahavira's soul, the last Jain Tirthankara of the present cosmic age. It is celebrated at the same time as the Hindu festival of Diwali. Diwali marks the New Year for Jains and commemorates the passing of their 24th Tirthankara Mahavira and his achievement of moksha.[146]

Adoration

.jpg)

The Svayambhustotra by Acharya Samantabhadra is the adoration of twenty-four Tirthankaras. Its eight shlokas (aphorisms) express adoration of the qualities of Mahavira.[147] One such shloka is:

O Lord Jina! Your doctrine that expounds essential attributes required of a potential aspirant to cross over the ocean of worldly existence (Saṃsāra) reigns supreme even in this strife-ridden spoke of time (Pancham Kaal). Accomplished sages who have invalidated the so-called deities that are famous in the world, and have made ineffective the whip of all blemishes, adore your doctrine.[148]

The Yuktyanusasana by Acharya Samantabhadra is a poetic work consisting of 64 verses in praise of Mahavira.[149]

Influence

Mahavira's teachings influenced many personalities. Rabindranath Tagore wrote:

Mahavira proclaimed in India that religion is a reality and not a mere social convention. It is really true that salvation can not be had by merely observing external ceremonies. Religion cannot make any difference between man and man.

A major event associated with the 2,500th anniversary of the Nirvana of Mahavira took place in 1974. According to Padmanabh Jaini:[150]

Probably few people in the West are aware that during this Anniversary year for the first time in their long history, the mendicants of the Śvētāmbara, Digambara and Sthānakavāsī sects assembled on the same platform, agreed upon a common flag (Jaina dhvaja) and emblem (pratīka); and resolved to bring about the unity of the community. For the duration of the year four dharma cakras, a wheel mounted on a chariot as an ancient symbol of the samavasaraṇa (Holy Assembly) of Tīrthaṅkara Mahavira traversed to all the major cities of India, winning legal sanctions from various state governments against the slaughter of animals for sacrifice or other religious purposes, a campaign which has been a major preoccupation of the Jainas throughout their history.

Iconography

Mahavira is usually depicted in a sitting or standing meditative posture with the symbol of a lion beneath him.[10] Every Tīrthankara has a distinguishing emblem that allows worshippers to distinguish similar-looking idols of the Tirthankaras.[151] The lion emblem of Mahavira is usually carved below the legs of the Tirthankara. Like all Tirthankaras, Mahavira is depicted with Shrivatsa[note 8] and downcast eyes.[154]

The earliest iconography for Mahavira is from archaeological sites in the north Indian city of Mathura. These are variously dated from the 1st century BC to the 2nd century AD.[155][156] The use of the srivatsa mark on Mahavira's chest, along with his dhyana-mudra posture, appears in Kushana Empire-era artwork. The differences in the Mahavira artwork between the Digambara and Svetambara traditions appear in the late 5th century AD and thereafter.[155] According to John Cort, the earliest archaeological evidence of Jina iconography with inscriptions precedes its datable texts by more than 250 years.[157]

Many images of Mahavira have been dated to be from the 12th-century and earlier.[158] An ancient sculpture of Mahavira was found in a cave at Sundarajapuram, Theni district, Tamil Nadu. K. Ajithadoss, a Jain scholar based in Chennai, dated the sculpture to the 9th century AD.[159]

The tallest known image of Lord Mahavira (in seated position)

The tallest known image of Lord Mahavira (in seated position) Four-sided sculpture depicting Mahavira (found during excavation at Kankali Tila, Mathura)

Four-sided sculpture depicting Mahavira (found during excavation at Kankali Tila, Mathura) Tirthankara Rishabhanatha (left) and Mahavira (right), 11th century. British Museum.

Tirthankara Rishabhanatha (left) and Mahavira (right), 11th century. British Museum.- Temple relief of Mahavira, 14th century. Seattle Asian Art Museum.

- Relief depicting Mahavira (Thirakoil, Tamil Nadu)

Mahavira Statue in Cave 32 of Ellora Caves

Mahavira Statue in Cave 32 of Ellora Caves

Temples

According to John Cort, the Mahavira temple at Osian, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, is the oldest Jain temple surviving in western India. It was constructed in the late 8th century AD.[161] Other temples of Mahavira include:

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mahavira. |

Notes

- ↑ Heinrich Zimmer: "The cycle of time continually revolves, according to the Jainas. The present "descending" (avasarpini) period was preceded and will be followed by an "ascending" (utsarpini). Sarpini suggests the creeping movement of a "serpent" ('sarpin'); ava- means "down" and ut- means up."[32]

- ↑ Trishala was the sister of King Chetaka of Vaishali in ancient India.[25]

- ↑ This mythology has similarities with those found in the mythical texts of the Vaishnavism tradition of Hinduism.[49]

- ↑ On this Champat Rai Jain wrote: ""Of the two versions of Mahavira's life — the Swetambara and the Digambara— it is obvious that only one can be true: either Mahavira married, or he did not marry. If Mahavira married, why should the Digambaras deny it? There is absolutely no reason for such a denial. The Digambaras acknowledge that nineteen out of the twenty-four Tirthamkaras married and had children. If Mahavira also married it would make no difference. There is thus no reason whatsoever for the Digambaras to deny a simple incident like this. But there may be a reason for the Swetambaras making the assertion; the desire to ante-date their own origin. As a matter of fact their own books contain clear refutation of the statement that Mahavira had married. In the Samavayanga Sutra (Hyderabad edition) it is definitely stated that nineteen Tirthankaras lived as householders, that is, all the twenty-four excepting Shri Mahavira, Parashva, Nemi, Mallinath and Vaspujya."[56]

- ↑ Not to be confused with Kevalajnana (omniscience), which he achieved at age 42.[80]

- ↑ Samaññaphala Sutta, D i.47: "Nigantha Nataputta answered with fourfold restraint. Just as if a person, when asked about a mango, were to answer with a breadfruit; or, when asked about a breadfruit, were to answer with a mango: In the same way, when asked about a fruit of the contemplative life, visible here and now, Nigantha Nataputta answered with fourfold restraint. The thought occurred to me: 'How can anyone like me think of disparaging a brahman or contemplative living in his realm?' Yet I [Buddha] neither delighted in Nigantha Nataputta's words nor did I protest against them. Neither delighting nor protesting, I was dissatisfied. Without expressing dissatisfaction, without accepting his teaching, without adopting it, I got up from my seat and left."[124]

- ↑ According to Melton and Baumann, the Digambaras state that "women's physical and emotional character makes it impossible for them to genuinely engage in the intense [ascetic] path necessary for spiritual purification. (...) Only by being reborn as a man can a woman engage in the ascetic path. Later Digambara secondary arguments appealed to human physiology in order to exclude women from the path: by their very biological basis, women constantly generate and destroy (and therefore harm) life forms within their sexual organs. Svetambara oppose this view by appealing to scriptures."[133]

- ↑ A special symbol that marks the chest of a Tirthankara. The yoga pose is very common in Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism. Each tradition has had a distinctive auspicious chest mark that allows devotees to identify a meditating statue to symbolic icon for their theology. There are several srivasta found in ancient and medieval Jain art works, and these are not found on Buddhist or Hindu art works.[152][153]

References

Citations

- ↑ Tandon 2002, p. 45.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Dundas 2002, p. 24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Taliaferro & Marty 2010, p. 126.

- ↑ "Mahavira" Archived 2017-05-13 at the Wayback Machine.. Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Doniger 1999, p. 549.

- 1 2 3 Potter 2007, pp. 35–36.

- 1 2 3 Dundas 2002, p. 22.

- ↑ Sharma & Sharma 2004, p. 39.

- ↑ Sharma & Khanna 2013, p. 18.

- 1 2 Umakant P. Shah 1987, p. 192.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dundas 2002, pp. 30–33.

- 1 2 Umakant P. Shah 1987, pp. 9–11.

- 1 2 3 Melton & Baumann 2010, p. 897.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dundas 2002, p. 25.

- ↑ Dundas 2002, pp. 25–26.

- 1 2 3 Winternitz 1993, p. 408.

- 1 2 Zimmer 1953, p. 223.

- ↑ von Dehsen 2013, p. 29.

- ↑ Kailash Chand Jain 1991, p. 31.

- 1 2 3 Heehs 2002, p. 93.

- 1 2 Kailash Chand Jain 1991, p. 32.

- ↑ Dundas 2002, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Pannalal Jain 2015, p. 460.

- ↑ Doniger 1999, p. 682.

- 1 2 3 4 von Glasenapp 1925, p. 29.

- ↑ Chaudhary, Pranava K (14 October 2003), "Row over Mahavira's birthplace", The Times of India, Patna, archived from the original on 3 November 2017

- ↑ Umakant P. Shah 1987, p. 3.

- ↑ Rapson 1955, pp. 155–156.

- ↑ Cort 2010, pp. 69–70, 587–588.

- ↑ Kailash Chand Jain 1991, pp. 74–85.

- ↑ Kailash Chand Jain 1991, pp. 84–88.

- 1 2 3 Zimmer 1953, p. 224.

- ↑ Jain & Upadhye 2000, p. 54.

- ↑ Zimmer 1953, p. 181.

- ↑ Upinder Singh 2016, pp. 312–313.

- ↑ Britannica Tirthankar Definition, Encyclopaedia Britannica

- ↑ George M. Williams 2008, pp. 52, 71.

- ↑ Evola 1996, p. 15.

- ↑ Zimmer 1953, pp. 220–226.

- ↑ von Glasenapp 1925, pp. 15–17.

- 1 2 3 Wiley 2009, p. 6.

- ↑ Dowling & Scarlett 2006, p. 225.

- ↑ Upinder Singh 2016, p. 313.

- 1 2 Gupta & Gupta 2006, p. 1001.

- 1 2 3 4 Dundas 2002, p. 21.

- ↑ Dundas 2002, pp. 21, 26.

- ↑ Mills, Claus & Diamond 2003, p. 320, note: Indra is referred to as Sakra in some Indian texts..

- ↑ Olivelle 2006, pp. 397 footnote 4.

- ↑ Mills, Claus & Diamond 2003, p. 320.

- ↑ Jain & Fischer 1978, pp. 5–9.

- ↑ Dalal 2010, p. 284.

- ↑ Dundas 2002, p. 30.

- ↑ Umakant P. Shah 1987, p. 99, Quote: "According to the Digambara sect, Mahavira did not marry, while the Svetambaras hold a contrary belief.".

- ↑ Shanti Lal Jain 1998, p. 51.

- ↑ Champat Rai Jain 1939, p. 97.

- ↑ Umakant P. Shah 1987, p. 188.

- ↑ Umakant P. Shah 1987, p. 95.

- ↑ von Glasenapp 1925, p. 16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 George 2008, p. 319.

- ↑ Jacobi 1964, p. 269.

- 1 2 Wiley 2009, pp. 5–7.

- ↑ von Glasenapp 1925, p. 30.

- ↑ Sen 1999, p. 74.

- ↑ Dundas 2002, p. 27.

- 1 2 3 von Glasenapp 1925, p. 327.

- ↑ Kailash Chand Jain 1991, p. 79.

- ↑ Jain & Upadhye 2000, p. 30.

- ↑ von Glasenapp 1925, p. 30, 327.

- ↑ Jain & Upadhye 2000, p. 31.

- ↑ Vijay K. Jain 2016b, p. 5.

- 1 2 Upinder Singh 2016, p. 314.

- 1 2 Wiley 2009, pp. 6–8, 26.

- ↑ George 2008, p. 326.

- ↑ Heehs 2002, p. 90.

- 1 2 von Glasenapp 1925, p. 39.

- 1 2 3 Caillat & Balbir 2008, p. 88.

- ↑ von Glasenapp 1925, pp. 30–31.

- 1 2 Doniger 1999, p. 549-550.

- ↑ von Glasenapp 1925, pp. 29–31, 205–206, Quote: "At the end of almost thirty years of preaching, he died in the chancellory of King Hastipala of Pavapuri and attained Nirvana.".

- ↑ Zimmer 1953, p. 222.

- ↑ Dundas 2002, p. 22-24.

- ↑ Pramansagar 2008, p. 38–39.

- ↑ von Glasenapp 1925, p. 328.

- ↑ "Destinations : Pawapuri". Bihar State Tourism Development Corporation. Archived from the original on 22 July 2015.

- ↑ Jain & Fischer 1978, pp. 14, 29–30.

- ↑ Jain & Upadhye 2000, p. 45.

- ↑ Jain & Upadhye 2000, p. 46.

- ↑ Kailash Chand Jain 1991, p. 59.

- ↑ Dundas 2002, p. 19.

- ↑ Jain & Upadhye 2000, p. 47.

- 1 2 Winternitz 1993, pp. 408–409.

- ↑ Cort 2010, p. 225.

- ↑ Vijay K. Jain 2012, p. xi.

- 1 2 Wiley 2009, pp. 6–8.

- ↑ Vijay K. Jain 2012, p. xii.

- ↑ Sangave 2006, p. 67.

- ↑ Shah, Umakant Premanand, Mahavira Jaina teacher, Encyclopædia Britannica, archived from the original on 5 September 2015

- 1 2 3 Shah, Pravin K (2011), Five Great Vows (Maha-vratas) of Jainism, Harvard University Literature Center, archived from the original on 31 December 2014

- ↑ Vijay K. Jain 2012, p. 68.

- ↑ Long 2009, p. 101–102.

- ↑ Long 2009, p. 109.

- ↑ Cort 2001, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Appleton 2014, pp. 20–45.

- ↑ Adams 2011, p. 22.

- ↑ Chakravarthi 2003, p. 3–22.

- 1 2 Dundas 2002, pp. 88–89, 257–258.

- ↑ Jain & Jain 2002, p. 13.

- ↑ Titze 1998, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Taylor 2008, pp. 892–894.

- ↑ Pandey 1998, p. 50.

- 1 2 Nanda 1997, p. 44.

- 1 2 Great Men's view on Jainism, archived from the original on 16 May 2018,

Jainism Literature Center

- ↑ "Anatta", Encyclopædia Britannica, 2013, archived from the original on 10 December 2015,

Anatta in Buddhism, the doctrine that there is in humans no permanent, underlying soul. The concept of anatta, or anatman, is a departure from the Hindu belief in atman (“the self”).

- ↑ Collins 1994, p. 64.

- ↑ Nagel 2000, p. 33.

- 1 2 Charitrapragya 2004, pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Dundas 2002, pp. 99–103.

- ↑ Dundas 2002, pp. 90–99.

- ↑ Dundas 2002, pp. 91–92, 104–105.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Charitrapragya 2004, pp. 75–79.

- ↑ Dundas 2002, pp. 229–231.

- 1 2 Jain philosophy Archived 21 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine., IEP, Mark Owen Webb, Texas Tech University

- ↑ Samaññaphala Sutta Archived 9 February 2014 at WebCite, Thanissaro Bhikkhu (1997)

- ↑ Matilal 1998, pp. 128–135.

- ↑ Matilal 1990, pp. 301–305.

- ↑ Balcerowicz 2015, pp. 205–218.

- 1 2 Dundas 2002, pp. 232–234.

- ↑ Long 2009, pp. 98–106.

- ↑ Dundas 2002, p. 233.

- ↑ Long 2009, pp. 36–37.

- 1 2 Harvey 2014, pp. 182–183.

- ↑ Melton & Baumann 2010, p. 1396.

- 1 2 Arvind Sharma 1994, pp. 135–138.

- ↑ Dundas 2002, pp. 55–59.

- ↑ Chapelle 2011, pp. 263–270.

- ↑ Dundas 2002, pp. 41–42, 90–93.

- 1 2 Long 2009, pp. 179–181.

- ↑ Gorski 2008, pp. 125–128.

- ↑ Wiley 2009, p. 5.

- ↑ Zimmer 1953, p. 226.

- ↑ Zimmer 1953, p. 220.

- ↑ von Glasenapp 1925, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Cort 2010, pp. 25–32, 120–122, 166–171, 189–192.

- ↑ George 2008, p. 394.

- ↑ Bhalla 2005, p. 13.

- ↑ Vijay K. Jain 2015, p. 164–169.

- ↑ Vijay K. Jain 2015, p. 165.

- ↑ Gokulchandra Jain 2015, p. 84.

- ↑ Jaini 2000, p. 31.

- ↑ Zimmer 1953, p. 225.

- ↑ von Glasenapp 1925, pp. 426–428.

- ↑ Jainism: Jinas and Other Deities Archived 26 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine., Victoria and Albert Museum, London

- ↑ Melton & Baumann 2010, p. 1553.

- 1 2 Umakant P. Shah 1995, pp. 15–17.

- ↑ Cort 2010, pp. 273–275.

- ↑ Cort 2010, pp. 48–49.

- ↑ Umakant P. Shah 1987, p. 193.

- ↑ Saju, M T (3 October 2015), "Ancient Mahavira sculpture found in cave near Theni", The Times of India, Chennai, archived from the original on 17 May 2017

- ↑ Titze 1998, p. 266.

- ↑ Cort 1998, p. 112.

Sources

- Adams, Simon (2011), The Story of World Religions, The Rosen Publishing Group, ISBN 978-1-4488-4791-4

- Appleton, Naomi (2014), Narrating Karma and Rebirth: Buddhist and Jain Multi-Life Stories, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-03393-1

- Balcerowicz, Piotr (2015), Early Asceticism in India: Ājīvikism and Jainism, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-317-53853-0

- Bhalla, Kartar Sing (2005), Let's Know Festivals of India, Star Publications, ISBN 9788176501651

- Caillat, Colette; Balbir, Nalini (1 January 2008), Jaina Studies (in Prakrit), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-3247-3

- Charitrapragya, Samani (2004), Sethia, Tara, ed., Ahimsā, Anekānta, and Jaininsm, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-2036-4

- Chakravarthi, Ram-Prasad (2003), "Non-violence and the other A composite theory of multiplism, heterology and heteronomy drawn from Jainism and Gandhi", Angelaki, 8 (3): 3–22, doi:10.1080/0969725032000154359

- Chapelle, Christopher (2011), Murphy, Andrew R., ed., The Blackwell Companion to Religion and Violence, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-1-4443-9573-0

- Collins, Steven (1994), Reynolds, Frank; Tracy, David, eds., Religion and Practical Reason, State Univ of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-2217-5

- Cort, John E., ed. (1998), Open Boundaries: Jain Communities and Cultures in Indian History, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-3785-8

- Cort, John E. (2001), Jains in the World: Religious Values and Ideology in India, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-513234-2

- Cort, John E. (2010), Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-538502-1

- Dalal, Roshen (2010), The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths, Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-14-341517-6

- Doniger, Wendy, ed. (1999), Encyclopedia of World Religions, Merriam-Webster, ISBN 978-0-87779-044-0

- Dowling, Elizabeth M.; Scarlett, W. George, eds. (2006), Encyclopedia of Religious and Spiritual Development, Sage Publications, ISBN 978-0-7619-2883-6

- Dundas, Paul (2002) [1992], The Jains (Second ed.), Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-26605-5

- Evola, Julius (1996), The Doctrine of Awakening: The Attainment of Self-Mastery According to the Earliest Buddhist Texts, Inner Traditions, ISBN 978-0-89281-553-1

- George, Vensus A. (2008), Paths to the Divine: Ancient and Indian, XII, The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy, ISBN 978-1-56518-248-6

- Gorski, Eugene F. (2008), Theology of Religions: A Sourcebook for Interreligious Study, Paulist Press, ISBN 978-0-8091-4533-1

- Gupta, K.R.; Gupta, Amita (2006), Concise Encyclopaedia of India, 3, Atlantic Publishers & Dis, ISBN 978-81-269-0639-0

- Harvey, Graham (2014) [2009], Religions in Focus: New Approaches to Tradition and Contemporary Practices, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-93690-8

- Heehs, Peter (2002), Indian Religions: A Historical Reader of Spiritual Expression and Experience, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, ISBN 978-1-85065-497-1

- Jacobi, Hermann (1964), Max Muller (The Sacred Books of the East Series, Volume XXII), ed., Jaina Sutras (Translation), Motilal Banarsidass (Original: Oxford University Press)

- Jain, Champat Rai (1939), The Change of Heart,

- Jain, Gokulchandra (2015), Samantabhadrabhāratī (1st ed.), Budhānā, Muzaffarnagar: Achārya Shāntisāgar Chani Smriti Granthmala, ISBN 978-81-90468879

- Jain, Hiralal; Jain, Dharmachandra (1 January 2002), Jaina Tradition in Indian Thought, ISBN 9788185616841

- Jain, Hiralal; Upadhye, Adinath Neminath (2000) [1974], Mahavira, his times and his philosophy of life, Bharatiya Jnanpith

- Jain, Jyotindra; Fischer, Eberhard (1978), Jaina Iconography, BRILL Academic, ISBN 978-90-04-05259-8

- Jain, Kailash Chand (1991), Lord Mahāvīra and His Times, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0805-8

- Jain, Shanti Lal (1998), ABC of Jainism, Bhopal (M.P.): Jnanodaya Vidyapeeth, ISBN 978-81-7628-000-6

- Jain, Vijay K. (2012), Acharya Amritchandra's Purushartha Siddhyupaya: Realization of the Pure Self, With Hindi and English Translation, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 978-81-903639-4-5,

- Jain, Vijay K. (2015), Acarya Samantabhadra's Svayambhustotra: Adoration of The Twenty-four Tirthankara, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 978-81-903639-7-6, archived from the original on 16 September 2015,

- Jain, Vijay K. (2016). Ācārya Samantabhadra's Ratnakarandaka-śrāvakācāra: The Jewel-casket of Householder's Conduct. Vikalp Printers. ISBN 978-81-903639-9-0.

- Jaini, Padmanabh S. (2000), Collected Papers on Jaina Studies, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publ., ISBN 978-81-208-1691-6

- Long, Jeffery D. (2009), Jainism: An Introduction, I. B. Tauris, ISBN 978-0-8577-3656-7

- Matilal, Bimal Krishna (1990), Logic, Language and Reality: Indian Philosophy and Contemporary Issues, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0717-4

- Matilal, Bimal Krishna (1998), Ganeri, Jonardon; Tiwari, Heeraman, eds., The Character of Logic in India, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-3739-1

- Melton, J. Gordon; Baumann, Martin, eds. (2010), Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices, One: A-B (Second ed.), ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-59884-204-3

- Mills, Margaret A.; Claus, Peter J.; Diamond, Sarah, eds. (2003), Kalpa Sutra (by Jerome Bauer) in South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-93919-5

- Nagel, Bruno (2000), Perrett, Roy, ed., Philosophy of Religion: Indian Philosophy, Routledge, ISBN 978-0815336112

- Nanda, R. T. (1997), Contemporary Approaches to Value Education in India, Regency Publications, ISBN 978-81-86030-46-2

- Olivelle, Patrick (2006), Between the Empires: Society in India 300 BCE to 400 CE, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-977507-1

- Pandey, Janardan (1998), Gandhi and 21st Century, ISBN 9788170226727

- Potter, Karl H. (2007), Dalsukh Malvania and Jayendra Soni, ed., Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies, X: Jain Philosophy, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-3169-8

- Pramansagar, Muni (2008), Jain Tattvavidya, India: Bhartiya Gyanpeeth, ISBN 978-81-263-1480-5

- Rapson, E.J. (1955), The Cambridge History of India, Cambridge University Press

- Sangave, Vilas Adinath (2001). Facets of Jainology: Selected Research Papers on Jain Society, Religion, and Culture. Mumbai: Popular Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-7154-839-2.

- Sangave, Vilas Adinath (2006) [1990], Aspects of Jaina religion (5 ed.), Bharatiya Jnanpith, ISBN 978-81-263-1273-3

- Sen, Shailendra Nath (1999) [1998], Ancient Indian History and Civilization (2nd ed.), New Age International, ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0

- Shah, Umakant Premanand (1987), Jaina-rūpa-maṇḍana: Jaina iconography, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 978-81-7017-208-6

- Shah, Umakant Premanand (1995), Studies in Jaina Art and Iconography and Allied Subjects in Honour of Dr. U.P. Shah, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 978-81-7017-316-8

- Sharma, Arvind (1994), Religion and Women, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-1689-1

- Sharma, Arvind; Khanna, Madhu (2013), Asian Perspectives on the World's Religions, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-0-313-37897-3

- Sharma, Suresh K.; Sharma, Usha (2004), Cultural and Religious Heritage of India: Jainism, Mittal Publications, ISBN 978-81-7099-957-7

- Singh, Upinder (2016), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Pearson Education, ISBN 978-93-325-6996-6

- Sunavala, A.J. (1934), Adarsha Sadhu: An Ideal Monk (First paperback edition, 2014 ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-62386-6

- Taliaferro; Marty (2010), A dictionary of philosophy of Religion, ISBN 978-1-4411-1197-5

- Tandon, Om Prakash (2002) [1968], Jaina Shrines in India (1 ed.), New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, ISBN 978-81-230-1013-7

- Taylor, Bron (2008), Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature, Bloomsbury Academic, ISBN 978-1-4411-2278-0

- Titze, Kurt (1998), Jainism: A Pictorial Guide to the Religion of Non-Violence (2 ed.), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1534-6

- von Dehsen, Christian (13 September 2013), Philosophers and Religious Leaders, Routledge, ISBN 978-81-208-1376-2

- von Glasenapp, Helmuth (1925), Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass (Reprinted 1999), ISBN 978-81-208-1376-2

- Wiley, Kristi L. (2009), The A to Z of Jainism, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 978-0-8108-6821-2

- Williams, George M. (2008), Handbook of Hindu Mythology, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-533261-2

- Winternitz, Moriz (1993), History of Indian Literature: Buddhist & Jain Literature, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0265-0

- Zimmer, Heinrich (1953) [April 1952], Campbell, Joseph, ed., Philosophies Of India, London, E.C. 4: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, ISBN 978-81-208-0739-6

External links

{{NIE Poster|year=1905| ![]()

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)