Buddhist meditation

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Mindfulness |

|---|

|

Other |

|

Similar concepts |

| Category:Mindfulness |

Buddhist meditation is the practice of meditation in Buddhism and Buddhist philosophy. It includes a variety of types of meditation.

Core meditation techniques have been preserved in ancient Buddhist texts and have proliferated and diversified through teacher-student transmissions. Buddhists pursue meditation as part of the path toward Enlightenment and Nirvana.[lower-alpha 1] The closest words for meditation in the classical languages of Buddhism are bhāvanā[lower-alpha 2] and jhāna/dhyāna.[lower-alpha 3] Buddhist meditation techniques have become increasingly popular in the wider world, with many non-Buddhists taking them up for a variety of reasons.

Buddhist meditation encompasses a variety of meditation techniques that aim to develop equanimity and sati (mindfulness); samadhi (concentration) c.q. samatha (tranquility) and vipassanā (insight); and abhijñā (supramundane powers). Specific Buddhist meditation techniques have also been used to remove unwholesome qualities thought to be impediments to spiritual liberation and develop wholesome qualities, such as loving kindness to remove ill-will, hate, and anger; equanimity to remove mental clinging; and patikulamanasikara (meditations on the parts of the body) and maraṇasati (meditation on death and corpses) to remove sensual lust for the body and cultivate impermanence (anicca). Given the large number and diversity of traditional Buddhist meditation practices, this article primarily identifies authoritative contextual frameworks—both contemporary and canonical—for the variety of practices. For those seeking school-specific meditation information, it may be more appropriate to simply view the articles listed in the "See also" section below.

While there are some similar meditative practices – such as breath meditation and various recollections (anussati) – that are used across Buddhist schools, there is also significant diversity. In the Theravada tradition alone, there are over fifty methods for developing mindfulness and forty for developing concentration, while in Tibetan Buddhism, there are thousands of visualization meditations.[lower-alpha 4] Most classical and contemporary Buddhist meditation guides are school specific.[lower-alpha 5] Only a few teachers attempt to synthesize, crystallize and categorize practices from multiple Buddhist traditions.

Overview

Most Buddhist traditions recognize that the path to awakening and liberation entails several aspects, including the study of the sutras, ethical conduct, meditation, insight, and compassion. The Tantric traditions add visualisations to this scheme.

Classic texts in the Pali literature enumerating meditative subjects include the Satipatthana Sutta (MN 10) and the Visuddhimagga's Part II, "Concentration" (Samadhi).

Dhyana may have been an original contribution of the Buddha,[1] together with the emphasis on mindfulness.[2][3][lower-alpha 6] In time, a growing emphasis was placed on insight, and in conjunction the original dhyana-scheme, which culminates in eqaunimity and mindfulness, was replaced with a sinplified meditation-method which emphasizes concentration (samadhi, samatha).[4][1][3] Likewise, whereas compassion and loving kindness may have been regarded as equally liberating in early Buddhism, they were relegated to a subsidiary role in later Theravada Buddhism,[5] though retaining their central place in Mahayana Buddhism.

The Theravada tradition, following the Noble Eightfold Path describes the Buddhist training as a threefold training: virtue (sīla); meditation (samadhi); and wisdom (paññā).[lower-alpha 7] Samadhi includes both Right Mindfulness (samma sati), exemplified by the Buddha's Four Foundations of Mindfulness, as described in the Satipatthana Sutta; and Right Concentration (samma samadhi); culminating in jhana/dhyana, interpreted as meditative absorption, through the meditative development of samatha.[6] Meditation is also implied in Right View (samma ditthi) &ndash, embodying wisdom which according to the Theravada tradition is attained through the meditative development of vipassana founded on samatha.[lower-alpha 8] Thus, meditative prowess alone is not sufficient; it is but one part of the path, in tandem with ethical development and wise understanding which are also necessary for the attainment of the highest goal.[7]

The Mahayana tradition emphasizes the combination of insight and compassion. Both dhyana (notably Zen) and samatha techniques can be found in the Mahayana traditions. The Six Perfections (pāramitā) echo the threefold training with the inclusion of virtue (śīla), concentration (samadhi) and wisdom (prajñā).

Early Buddhism

Pre-Buddhist India

The two major traditions of meditative practice in pre-Buddhist India were the Jain ascetic practices and the various Vedic Brahmanical practices. There is still much debate in Buddhist studies regarding how much influence these two traditions had on the development of early Buddhist meditation. The early Buddhist texts mention that the Gautama trained under two teachers known as Āḷāra Kālāma and Uddaka Rāmaputta, both of them taught formless jhanas or mental absorptions, a key practice of proper Buddhist meditation.[8] Alexander Wynne considers these figures historical persons associated with the doctrines of the early Upanishads.[9] Other practices which the Buddha undertook have been associated with the Jain ascetic tradition by the Indologist Johannes Bronkhorst including extreme fasting and a forceful "meditation without breathing".[10] According to the early texts, the Buddha rejected the more extreme Jain ascetic practices in favor of the middle way.

Pre-sectarian Buddhism

Modern Buddhist studies has attempted to reconstruct the meditation practices of pre-sectarian Early Buddhism, mainly through philological and text critical methods using the early canonical texts.[11]

According to Bronkhorst, the oldest Buddhist meditation practice are the four dhyanas, which lead to the destruction of the asavas as well as the practice of mindfulness (sati).[12] Alexander Wynne agrees that the Buddha taught a kind of meditation exemplified by the four dhyanas, arguing that the Buddha adopted these from the Brahmin teachers Āḷāra Kālāma and Uddaka Rāmaputta, though he did not interpret them in the same Vedic cosmological way and rejected their Vedic goal (union with Brahman). The Buddha, according to Wynne, radically transformed the practice of dhyana which he learned from these Brahmins which "consisted of the adaptation of the old yogic techniques to the practice of mindfulness and attainment of insight".[13] For Wynne, this idea that liberation required not just meditation but an act of insight, was radically different than the Brahminic meditation, "where it was thought that the yogin must be without any mental activity at all, ‘like a log of wood’."[14]

According to Indologist Johannes Bronkhorst, "the teaching of the Buddha as presented in the early canon contains a number of contradictions,"[15] presenting "a variety of methods that do not always agree with each other,"[16] containing "views and practices that are sometimes accepted and sometimes rejected."[15] These contradictions are due to the influence of non-Buddhist traditions on early Buddhism. One example of these non-Buddhist meditative methods found in the early sources is outlined by Bronkhorst:

The Vitakkasanthāna Sutta of the Majjhima Nikāya and its parallels in Chinese translation recommend the practicing monk to ‘restrain his thought with his mind, to coerce and torment it’. Exactly the same words are used elsewhere in the Pāli canon (in the Mahāsaccaka Sutta, Bodhirājakumāra Sutta and Saṅgārava Sutta) in order to describe the futile attempts of the Buddha before his enlightenment to reach liberation after the manner of the Jainas.[11]

According to Bronkhorst, such practices which are based on a "suppression of activity" are not authentically Buddhist, but were later adopted from the Jains by the Buddhist community.

Dhyāna/Jhāna

Many scholars of early Buddhism, such as Vetter, Bronkhorst and Anālayo, see the practice of absorption (Pāli: jhāna, Sanskrit: dhyāna) as central to the meditation of Early Buddhism.[17][18][19] There are four form jhanas, each one more subtle and refined. The qualities associated with the first four jhanas are as follows:[20][lower-alpha 9]

- First dhyana: rapture & pleasure born from withdrawal, accompanied by directed thought & evaluation

- Second dhyana: rapture & pleasure born of composure, unification of awareness free from directed thought & evaluation—internal assurance

- Third dhyana: equanimous, mindful, & alert, and senses pleasure with the body

- Fourth dhyana: purity of equanimity & mindfulness, neither-pleasure-nor-pain

According to Richard Gombrich, the sequence of the four rupa-jhanas describes two different cognitive states.[21][lower-alpha 10][22] Alexander Wynne further explains that the dhyana-scheme is poorly understood.[23] According to Wynne, words expressing the inculcation of awareness, such as sati, sampajāno, and upekkhā, are mistranslated or understood as particular factors of meditative states,[23] whereas they refer to a particular way of perceiving the sense objects.[23][lower-alpha 11][lower-alpha 12]

In addition to the four rūpajhānas, there are also meditative attainments which were later called by the tradition the arūpajhānas, though the early texts do not use the term dhyana for them, calling them āyatana (dimension, sphere, base). They are:

- The Dimension of infinite space (Pali ākāsānañcāyatana, Skt. ākāśānantyāyatana),

- The Dimension of infinite consciousness (Pali viññāṇañcāyatana, Skt. vijñānānantyāyatana),

- The Dimension of infinite nothingness (Pali ākiñcaññāyatana, Skt. ākiṃcanyāyatana),

- The Dimension of neither perception nor non-perception (Pali nevasaññānāsaññāyatana, Skt. naivasaṃjñānāsaṃjñāyatana).

- Nirodha-samāpatti, also called saññā-vedayita-nirodha, 'extinction of feeling and perception'.

These formless jhanas may have been incorporated from non-Buddhist traditions.[1][3]

Mindfulness and Satipatthana

An important quality to be cultivated by a Buddhist meditator is mindfulness (sati). Mindfulness is a polyvalent term which refers to remembering, recollecting and "bearing in mind". It also relates to remembering the teachings of the Buddha and knowing how these teachings relate to one's experiences. The Buddhist texts mention different kinds of mindfulness practice. According to Bronkhorst, there were originally two kinds of mindfulness, “observations of the positions of the body” and the 4 satipaṭṭhānas which constituted formal meditation.[26] Bhikkhu Sujato and Bronkhorst both argue that the mindfulness of the positions of the body wasn't originally part of the four satipatthana formula, but was later added to it in some texts.[27]

In the Pali Satipatthana Sutta and its parallels as well as numerous other early Buddhist texts, the Buddha identifies four foundations for mindfulness (satipaṭṭhānas): the body (including the four elements, the parts of the body, and death), feelings (vedana), mind (citta) and phenomena or principles (dhammas), such as the five hindrances and the seven factors of enlightenment. Different early texts give different enumerations of these four mindfulness practices. Meditation on these subjects is said to develop insight.[28]

Serenity and insight

Mental qualities

The Buddha is said to have identified two paramount mental qualities that arise from wholesome meditative practice:

- "serenity" or "tranquillity" (Pali: samatha) which steadies, composes, unifies and concentrates the mind;

- "insight" (Pali: vipassanā) which enables one to see, explore and discern "formations" (conditioned phenomena based on the five aggregates).[lower-alpha 13]

In the Pali canon, the Buddha never mentions independent samatha and vipassana meditation practices; instead, samatha and vipassana are two qualities of mind, to be developed through meditation.[lower-alpha 14] Nonetheless, some meditation practices (such as contemplation of a kasina object) favor the development of samatha, others are conducive to the development of vipassana (such as contemplation of the aggregates), while others (such as mindfulness of breathing) are classically used for developing both mental qualities.[29]

Through the meditative development of serenity, one is able to suppress obscuring hindrances; and, with the suppression of the hindrances, it is through the meditative development of insight that one gains liberating wisdom.[30] Moreover, the Buddha is said to have extolled serenity and insight as conduits for attaining Nibbana (Pali; Skt.: Nirvana), the unconditioned state as in the "Kimsuka Tree Sutta" (SN 35.245), where the Buddha provides an elaborate metaphor in which serenity and insight are "the swift pair of messengers" who deliver the message of Nibbana via the Noble Eightfold Path.[lower-alpha 15] In the Threefold training, samatha is part of samadhi, the eight limb of the threefold path, together withsati, mindfulness.

Order of development

In the "Four Ways to Arahantship Sutta" (AN 4.170), Ven. Ananda reports that people attain arahantship using serenity and insight in one of three ways:

- they develop serenity and then insight (Pali: samatha-pubbangamam vipassanam)

- they develop insight and then serenity (Pali: vipassana-pubbangamam samatham){{While the Nikayas identify that the pursuit of vipassana can precede the pursuit of samatha, a fruitful vipassana-oriented practice must still be based upon the achievement of stabilizing "access concentration" (Pali: upacara samadhi).}}

- they develop serenity and insight in tandem (Pali: samatha-vipassanam yuganaddham) as in, for instance, obtaining the first jhana, and then seeing in the associated aggregates the three marks of existence, before proceeding to the second jhana.[31]

According to Anālayo, the jhanas are crucial meditative states which lead to the abandonment of hindrances such as lust and aversion; however, they are not sufficient for the attainment of liberating insight. Some early texts also warn meditators against becoming attached to them, and therefore forgetting the need for the further practice of insight.[32]

According to Anālayo, "either one undertakes such insight contemplation while still being in the attainment, or else one does so retrospectively, after having emerged from the absorption itself but while still being in a mental condition close to it in concentrative depth."[33] The position that insight can be practiced from within jhana, according to the early texts, is endorsed by Gunaratna, Crangle and Shankaman.[34][35][36] Anālayo meanwhile argues, that the evidence from the early texts suggest that "contemplation of the impermanent nature of the mental constituents of an absorption takes place before or on emerging from the attainment".[37]

Insight as a later development

Various early sources mention the attainment of insight after having achieved jhana. In the Mahasaccaka Sutta, dhyana is followed by insight into the four noble truths. The mention of the four noble truths as constituting "liberating insight" is probably a later addition.[38][39][1][3] Originally the practice of dhyana itself may have constituted the core liberating practice of early Buddhism, since in this state all "pleasure and pain" had waned.[40] According to Vetter,

[P]robably the word "immortality" (a-mata) was used by the Buddha for the first interpretation of this experience and not the term cessation of suffering that belongs to the four noble truths [...] the Buddha did not achieve the experience of salvation by discerning the four noble truths and/or other data. But his experience must have been of such a nature that it could bear the interpretation "achieving immortality".[41]

Discriminating insight into transiency as a separate path to liberation was a later development,[42][43] under pressure of developments in Indian religious thinking, which saw "liberating insight" as essential to liberation.[40] This may also have been due to an over-literal interpretation by later scholastics of the terminology used by the Buddha,[44] and to the problems involved with the practice of dhyana, and the need to develop an easier method.[45]

Brahmavihāra

Another important meditation in the early sources are the four Brahmavihāra (divine abodes) which are said to lead to cetovimutti, a “liberation of the mind”.[46] The four Brahmavihāra are:

- Loving-kindness (Pāli: mettā, Sanskrit: maitrī) is active good will towards all;[47][48]

- Compassion (Pāli and Sanskrit: karuṇā) results from metta, it is identifying the suffering of others as one's own;[47][48]

- Empathetic joy (Pāli and Sanskrit: muditā): is the feeling of joy because others are happy, even if one did not contribute to it, it is a form of sympathetic joy;[47]

- Equanimity (Pāli: upekkhā, Sanskrit: upekṣā): is even-mindedness and serenity, treating everyone impartially.[47][48]

According to Anālayo:

The effect of cultivating the brahmavihāras as a liberation of the mind finds illustration in a simile which describes a conch blower who is able to make himself heard in all directions. This illustrates how the brahmavihāras are to be developed as a boundless radiation in all directions, as a result of which they cannot be overruled by other more limited karma.[49]

The practice of the four divine abodes can be seen as a way to overcome ill-will and sensual desire and to train in the quality of deep concentration (samadhi).[50]

Theravada tradition

Buddhaghosa

The oldest material of the Theravada tradition on meditation can be found in the Pali Nikayas and in texts such as the Patisambhidamagga which provide commentary to meditation suttas like the Anapanasati sutta. An early Theravada meditation manual is the Vimuttimagga ('Path of Freedom', 1st or 2nd century).[51] The most influential presentation though, is that of the 5th Century Visuddhimagga ('Path of Purification') of Buddhaghoṣa, which describes forty meditation subjects. Almost all of these are described in the early texts.[52] Buddhaghoṣa also seems to have been influenced by the earlier Vimuttimagga in his presentation.[53]

Buddhaghoṣa advises that, for the purpose of developing concentration and consciousness, a person should "apprehend from among the forty meditation subjects one that suits his own temperament" with the advice of a "good friend" (kalyāṇa-mittatā) who is knowledgeable in the different meditation subjects (Ch. III, § 28).[54] Buddhaghoṣa subsequently elaborates on the forty meditation subjects as follows (Ch. III, §104; Chs. IV–XI):[55]

- ten kasinas: earth, water, fire, air, blue, yellow, red, white, light, and "limited-space".

- ten kinds of foulness: "the bloated, the livid, the festering, the cut-up, the gnawed, the scattered, the hacked and scattered, the bleeding, the worm-infested, and a skeleton".

- ten recollections: Buddhānussati, the Dhamma, the Sangha, virtue, generosity, the virtues of deities, death (see the Upajjhatthana Sutta), the body, the breath (see anapanasati), and peace (see Nibbana).

- four divine abodes: mettā, karuṇā, mudita, and upekkha.

- four immaterial states: boundless space, boundless perception, nothingness, and neither perception nor non-perception.

- one perception (of "repulsiveness in nutriment")

- one "defining" (that is, the four elements)

When one overlays Buddhaghosa's 40 meditative subjects for the development of concentration with the Buddha's foundations of mindfulness, three practices are found to be in common: breath meditation, foulness meditation (which is similar to the Sattipatthana Sutta's cemetery contemplations, and to contemplation of bodily repulsiveness), and contemplation of the four elements. According to Pali commentaries, breath meditation can lead one to the equanimous fourth jhanic absorption. Contemplation of foulness can lead to the attainment of the first jhana, and contemplation of the four elements culminates in pre-jhana access concentration.[56]

Contemporary Theravada

Particularly influential from the twentieth century onward has been the "New Burmese Method" or "Vipassanā School" approach to samatha and vipassanā developed by Mingun Sayadaw and U Nārada and popularized by Mahasi Sayadaw. Here samatha is considered an optional but not necessary component of the practice—vipassanā is possible without it. Another Burmese method, derived from Ledi Sayadaw via Ba Khin and S. N. Goenka, takes a similar approach. Other Burmese traditions popularized in the west, notably that of Pa Auk Sayadaw, uphold the emphasis on samatha explicit in the commentarial tradition of the Visuddhimagga. These Burmese traditions have been particularly influential on the Western Vipassana movement (also called "Insight meditation"), which includes American Buddhist teachers such as Joseph Goldstein, Sharon Salzberg and Jack Kornfield.

There are also other less well known Burmese meditation methods, such as the system developed by U Vimala, which focuses on knowledge of dependent origination and cittanupassana (mindfulness of the mind).[57] Likewise, Sayadaw U Tejaniya's method also focuses on mindfulness of the mind.

Also influential is the Thai Forest Tradition deriving from Mun Bhuridatta and popularized by Ajahn Chah, which, in contrast, stresses the inseparability of the two practices, and the essential necessity of both practices. Other noted practitioners in this tradition include Ajahn Thate and Ajahn Maha Bua, among others.[58] There are other forms of Thai Buddhist meditation associated with particular teachers, including Buddhadasa Bhikkhu's presentation of anapanasati, Ajahn Lee's breath meditation method (which influenced his American student Thanissaro) and the "dynamic meditation" of Luangpor Teean Cittasubho.[59]

There are other less mainstream forms of Theravada meditation practiced in Thailand which include the vijja dhammakaya meditation developed by Luang Pu Sodh Candasaro and the meditation of former supreme patriarch Suk Kai Thuean (1733–1822).[60] Newell notes that these two forms of modern Thai meditation share certain features in common with tantric practices such as the use of visualizations and centrality of maps of the body.[61]

A less common type of meditation is practiced in Cambodia and Laos by followers of Borān kammaṭṭhāna ('ancient practices') tradition. This form of meditation includes the use of mantras and visualizations.

Sarvāstivāda

The now defunct Sarvāstivāda tradition and its related sub-schools like the Sautrāntika and the Vaibhāṣika were the most influential Buddhists in North India and Central Asia. Their highly complex Abhidharma treatises such as the Mahavibhasa, the Sravakabhumi and the Abhidharmakosha contain new developments in meditative theory which are a major influence on meditation as practiced in East Asian Mahayana and Tibetan Buddhism. Individuals known as yogācāras (yoga practitioners) were influential in the development of Sarvāstivāda meditation praxis and some modern scholars such as Yin Shun believe they were also influential in the development of Mahayana meditation.[62]

According to KL Dhammajoti, the Sarvāstivāda meditation practitioner begins with samatha meditations, divided into the five fold mental stillings, each being recommended as useful for particular personality types:

- contemplation on the impure (asubhabhavana), for the greedy type person.

- meditation on loving kindness (maitri), for the hateful type

- contemplation on conditioned co-arising, for the deluded type

- contemplation on the division of the dhatus, for the conceited type

- mindfulness of breathing (anapanasmrti), for the distracted type.[63]

Contemplation of the impure and mindfulness of breathing was particularly important in this system and they were known as the 'gateways to immortality' (amrta-dvāra).[64] The Sarvāstivāda system practiced breath meditation using the same sixteen aspect model used in the anapanasati sutta and also introduced a unique six aspect system which consists of: (1) counting the breaths up to ten, (2) following the breath as it enters through the nose throughout the body, (3) fixing the mind on the breath, (4) observing the breath at various locations, (5) modifying is related to the practice of the four applications of mindfulness and (6) purifying stage of the arising of insight.[65] This six fold breathing meditation method was influential in East Asia and expanded upon by the Chinese Tiantai meditation master Zhiyi.[63] After the practitioner has achieved tranquility, Sarvāstivāda Abhidharma then recommends one proceeds to practice the four applications of mindfulness (smrti-upasthāna) in two ways. First they contemplate each specific characteristic of the four applications of mindfulness and then they contemplate all four collectively.[66] In spite of this systematic division of samatha and vipasyana, the Sarvāstivāda Abhidharmikas held that the two practices are not mutually exclusive. The Mahavibhasa for example remarks that, regarding the six aspects of mindfulness of breathing, "there is no fixed rule here — all may come under samatha or all may come under vipasyana."[67] The Sarvāstivāda Abhidharmikas also held that attaining the dhyānas was necessary for the development of insight and wisdom.[67]

Mahāyāna Buddhism

Mahāyāna Buddhism includes numerous schools of practice, which each draw upon various Buddhist sūtras, philosophical treatises, and commentaries. Accordingly, each school has its own meditation methods for the purpose of developing samādhi and prajñā, with the goal of ultimately attaining enlightenment. Nevertheless, each has its own emphasis, mode of expression, and philosophical outlook. In his classic book on meditation of the various Chinese Buddhist traditions, Charles Luk writes, "The Buddha Dharma is useless if it is not put into actual practice, because if we do not have personal experience of it, it will be alien to us and we will never awaken to it in spite of our book learning."[68] Nan Huaijin echoed similar sentiments about the importance of meditation by remarking, "Intellectual reasoning is just another spinning of the sixth consciousness, whereas the practice of meditation is the true entry into the Dharma."[69]

Initially, Mahayana Buddhists in India and East Asia practiced meditation in a similar way to that of the Sarvāstivāda school outlined above. One of the major Indian Mahayana treatises on meditation practice is the Yogacara bhumi (compiled circa late 4th century), a compendium of texts which includes within it the Sarvāstivāda Sravakabhūmi (c. 2nd-3rd century) as well as the Mahayana Bodhisattvabhūmi (c. 3rd century).[70]

The works of the Chinese translator An Shigao (安世高, 147-168 CE) are some of the earliest meditation texts used by Chinese Buddhism and their focus is mindfulness of breathing (annabanna 安那般那), these texts are known as the Dhyāna sutras.[71] The Chinese translator and scholar Kumarajiva (344–413 CE) transmitted a meditation treatise titled The Sūtra Concerned with Samādhi in Sitting Meditation (坐禅三昧经, T.614, K.991) which teaches the Sarvāstivāda system of five fold mental stillings.[72]

Meditation in the Pure Land school

Mindfulness of Amitābha Buddha

In Pure Land Buddhism, repeating the name of Amitābha is traditionally a form of mindfulness of the Buddha (Skt. buddhānusmṛti). This term was translated into Chinese as nianfo (Chinese: 念佛), by which it is popularly known in English. The practice is described as calling the buddha to mind by repeating his name, to enable the practitioner to bring all his or her attention upon that buddha (samādhi).[73] This may be done vocally or mentally, and with or without the use of Buddhist prayer beads. Those who practice this method often commit to a fixed set of repetitions per day, often from 50,000 to over 500,000.[74] According to tradition, the second patriarch of the Pure Land school, Shandao, is said to have practiced this day and night without interruption, each time emitting light from his mouth. Therefore, he was bestowed with the title "Great Master of Light" (大師光明) by Emperor Gaozong of Tang (高宗).[75]

In addition, in Chinese Buddhism there is a related practice called the "dual path of Chán and Pure Land cultivation", which is also called the "dual path of emptiness and existence."[76] As taught by Venerable Nan Huaijin, the name of Amitābha Buddha is recited slowly, and the mind is emptied out after each repetition. When idle thoughts arise, the phrase is repeated again to clear them. With constant practice, the mind is able to remain peacefully in emptiness, culminating in the attainment of samādhi.[77]

Pure Land Rebirth Dhāraṇī

Repeating the Pure Land Rebirth dhāraṇī is another method in Pure Land Buddhism. Similar to the mindfulness practice of repeating the name of Amitābha Buddha, this dhāraṇī is another method of meditation and recitation in Pure Land Buddhism. The repetition of this dhāraṇī is said to be very popular among traditional Chinese Buddhists.[78] It is traditionally preserved in Sanskrit, and it is said that when a devotee succeeds in realizing singleness of mind by repeating a mantra, its true and profound meaning will be clearly revealed.[79]

- namo amitābhāya tathāgatāya tadyathā

- amṛtabhave amṛtasaṃbhave

- amṛtavikrānte amṛtavikrāntagāmini

- gagana kīrtīchare svāhā

Visualization methods

Another practice found in Pure Land Buddhism is meditative contemplation and visualization of Amitābha, his attendant bodhisattvas, and the Pure Land. The basis of this is found in the Amitāyurdhyāna Sūtra ("Amitābha Meditation Sūtra"), in which the Buddha describes to Queen Vaidehi the practices of thirteen progressive visualization methods, corresponding to the attainment of various levels of rebirth in the Pure Land.[80] Visualization practises for Amitābha are popular among esoteric Buddhist sects, such as Japanese Shingon Buddhism.

Meditation in the Chán/Zen school

Pointing to the nature of the mind

In the earliest traditions of Zen, it is said that there was no formal method of meditation. Instead, the teacher would use various didactic methods to point to the true nature of the mind, also known as Buddha-nature. This method is referred to as the "Mind Dharma", and exemplified in the story of Śākyamuni Buddha holding up a flower silently, and Mahākāśyapa smiling as he understood.[81] A traditional formula of this is, "Chán points directly to the human mind, to enable people to see their true nature and become buddhas."[82] In the early era of the Chán school, there was no fixed method or ple formula for teaching meditation, and all instructions were simply heuristic methods; therefore the Chán school was called the "Gateless Gate."[83]

Contemplating meditation cases

It is said traditionally that when the minds of people in society became more complicated and when they could not make progress so easily, the masters of the Chán school were forced to change their methods.[84] These involved particular words and phrases, shouts, roars of laughter, sighs, gestures, or blows from a staff. These were all meant to awaken the student to the essential truth of the mind, and were later called gōng'àn (公案), or kōan in Japanese.[85] These didactic phrases and methods were to be contemplated, and example of such a device is a phrase that turns around the practice of mindfulness: "Who is being mindful of the Buddha?"[86] The teachers all instructed their students to give rise to a gentle feeling of doubt at all times while practicing, so as to strip the mind of seeing, hearing, feeling, and knowing, and ensure its constant rest and undisturbed condition.[87] Charles Luk explains the essential function of contemplating such a meditation case with doubt:

Since the student cannot stop all his thoughts at one stroke, he is taught to use this poison-against-poison device to realize singleness of thought, which is fundamentally wrong but will disappear when it falls into disuse, and gives way to singleness of mind, which is a precondition of the realization of the self-mind for the perception of self-nature and attainment of Bodhi.[88]

Meditation in the Tiantai school

Tiantai śamatha-vipaśyanā

In China it has been traditionally held that the meditation methods used by the Tiantai school are the most systematic and comprehensive of all.[89] In addition to its doctrinal basis in Indian Buddhist texts, the Tiantai school also emphasizes use of its own meditation texts which emphasize the principles of śamatha and vipaśyanā. Of these texts, Zhiyi's Concise Śamathavipaśyanā (小止観), Mohe Zhiguan (摩訶止観, Sanskrit Mahāśamathavipaśyanā), and Six Subtle Dharma Gates (六妙法門) are the most widely read in China.[90] Rujun Wu identifies the work Mahā-śamatha-vipaśyanā of Zhiyi as the seminal meditation text of the Tiantai school.[91] Regarding the functions of śamatha and vipaśyanā in meditation, Zhiyi writes in his work Concise Śamatha-vipaśyanā:

The attainment of Nirvāṇa is realizable by many methods whose essentials do not go beyond the practice of śamatha and vipaśyanā. Śamatha is the first step to untie all bonds and vipaśyanā is essential to root out delusion. Śamatha provides nourishment for the preservation of the knowing mind, and vipaśyanā is the skillful art of promoting spiritual understanding. Śamatha is the unsurpassed cause of samādhi, while vipaśyanā begets wisdom.[92]

The Tiantai school also places a great emphasis on ānāpānasmṛti, or mindfulness of breathing, in accordance with the principles of śamatha and vipaśyanā. Zhiyi classifies breathing into four main categories: panting (喘), unhurried breathing (風), deep and quiet breathing (氣), and stillness or rest (息). Zhiyi holds that the first three kinds of breathing are incorrect, while the fourth is correct, and that the breathing should reach stillness and rest.[93] Zhiyi also outlines four kinds of samadhi in his Mohe Zhiguan, and ten modes of practicing vipaśyanā.

Esoteric practices in Japan

One of the adaptations by the Japanese Tendai school was the introduction of Mikkyō (esoteric practices) into Buddhism, which was later named Taimitsu by Ennin. Eventually, according to Tendai Taimitsu doctrine, the esoteric rituals came to be considered of equal importance with the exoteric teachings of the Lotus Sutra. Therefore, by chanting mantras, maintaining mudras, or performing certain meditations, one is able to see that the sense experiences are the teachings of Buddha, have faith that one is inherently an enlightened being, and one can attain enlightenment within this very body. The origins of Taimitsu are found in China, similar to the lineage that Kūkai encountered in his visit to Tang China and Saichō's disciples were encouraged to study under Kūkai.[94]

Meditation in Vajrayana Buddhism

Vajrayana Buddhism includes all of the traditional forms of Mahayana meditation and also several unique forms. The central defining form of Vajrayana meditation is Deity Yoga (devatayoga).[95] This involves the recitation of mantras, prayers and visualization of the yidam or deity along with the associated mandala of the deity's Pure Land.[96] Advanced Deity Yoga involves imagining yourself as the deity.

Other forms of meditation in Vajrayana include the Mahamudra and Dzogchen teachings, each taught by the Kagyu and Nyingma lineages of Tibetan Buddhism respectively. The goal of these is to familiarize oneself with the ultimate nature of mind which underlies all existence, the Dharmakāya. There are also other practices such as Dream Yoga, Tummo, the yoga of the intermediate state (at death) or Bardo, sexual yoga and Chöd.

The shared preliminary practices of Tibetan Buddhism are called ngöndro, which involves visualization, mantra recitation, and many prostrations.

Therapeutic uses of meditation

For a long time people have practiced meditation, based on Buddhist meditation principles, in order to effect mundane and worldly benefit.[97] As such, mindfulness and other Buddhist meditation techniques are being advocated in the West by innovative psychologists and expert Buddhist meditation teachers such as Thích Nhất Hạnh, Pema Chödrön, Clive Sherlock, Mya Thwin, S. N. Goenka, Jon Kabat-Zinn, Jack Kornfield, Joseph Goldstein, Tara Brach, Alan Clements, and Sharon Salzberg, who have been widely attributed with playing a significant role in integrating the healing aspects of Buddhist meditation practices with the concept of psychological awareness, healing, and well-being. Although mindfulness meditation[98] has received the most research attention, loving kindness[99] (metta) and equanimity[100] (upekkha) meditation are beginning to be used in a wide array of research in the fields of psychology and neuroscience.

The accounts of meditative states in the Buddhist texts are in some regards free of dogma, so much so that the Buddhist scheme has been adopted by Western psychologists attempting to describe the phenomenon of meditation in general.[lower-alpha 16] However, it is exceedingly common to encounter the Buddha describing meditative states involving the attainment of such magical powers (Sanskrit ṛddhi, Pali iddhi) as the ability to multiply one's body into many and into one again, appear and vanish at will, pass through solid objects as if space, rise and sink in the ground as if in water, walking on water as if land, fly through the skies, touching anything at any distance (even the moon or sun), and travel to other worlds (like the world of Brahma) with or without the body, among other things,[101][102][103] and for this reason the whole of the Buddhist tradition may not be adaptable to a secular context, unless these magical powers are seen as metaphorical representations of powerful internal states that conceptual descriptions could not do justice to.

Key Terms

| English | Pali | Sanskrit | Chinese | Tibetan |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mindfulness/awareness | sati | smṛti | 念 (niàn) | trenpa (wylie: dran pa) |

| clear comprehension | sampajañña | samprajaña | 正知力 (zhèng zhī lì) | shezhin (shes bzhin) |

| vigilance/heedfulness | appamada | apramāda | 不放逸座 (bù fàng yì zuò) | bakyö (bag yod) |

| ardency | atappa | ātapaḥ | 勇猛 (yǒng měng) | nyima (nyi ma) |

| attention/engagement | manasikara | manaskāraḥ | 如理作意 (rú lǐ zuò yì) | yila jepa (yid la byed pa) |

| foundation of mindfulness | satipaṭṭhāna | smṛtyupasthāna | 念住 (niànzhù) | trenpa neybar zhagpa (dran pa nye bar gzhag pa) |

| mindfulness of breathing | ānāpānasati | ānāpānasmṛti | 安那般那 (ānnàbānnà) | wūk trenpa (dbugs dran pa) |

| calm abiding/cessation | samatha | śamatha | 止 (zhǐ) | shiney (zhi gnas) |

| insight/contemplation | vipassanā | vipaśyanā | 観 (guān) | lhagthong (lhag mthong) |

| meditative concentration | samādhi | samādhi | 三昧 (sānmèi) | ting-nge-dzin (ting nge dzin) |

| meditative absorption | jhāna | dhyāna | 禪 (chán) | samten (bsam gtan) |

| cultivation | bhāvanā | bhāvanā | 修行 (xiūxíng) | gompa (sgom pa) |

| cultivation of analysis | Vitakka and Vicāra | *vicāra-bhāvanā | 尋伺察 (xún sì chá) | chegom (dpyad sgom) |

| cultivation of settling | — | *sthāpya-bhāvanā | — | jokgom ('jog sgom) |

See also

Theravada Buddhist meditation practices:

- Anapanasati – focusing on the breath

- Satipatthana – Mindfulness of body, sensations, mind and mental phenomena

- The Four Immeasurables – including compassion karuna and loving-kindness Metta

- Kammaṭṭhāna

- Buddhānusmṛti – devotional meditation

- Samatha – calm abiding

- Vipassana – insight

- Mahasati Meditation

- Dhammakaya Meditation

Zen Buddhist meditation practices:

- Shikantaza – just sitting

- Kinhin

- Zazen

- Koan

- Hua Tou

- Suizen (historically practiced by the Fuke sect)

Buddhist meditation centers:

- Insight Meditation Society – Insight meditation, Barre, Massachusetts, United States

- Dharma Drum Retreat Center – Ch'an/Zen Buddhist meditation center in Pine Bush, New York, United States

- Padmaloka Buddhist Retreat Centre Triratna center for men in Norfolk, UK

- Chapin Mill Zen Buddhist meditation center in Rochester, New York, United States

- Furnace Mountain Zen Buddhist meditation center in Kentucky, United States

- San Francisco Zen Center

Vajrayana and Tibetan Buddhist meditation practices:

- Deity yoga

- Ngondro – preliminary practices

- Tonglen – giving and receiving

- Phowa – transference of consciousness at the time of death

- Chöd – cutting through fear by confronting it

- Mahamudra – the Kagyu version of 'entering the all-pervading Dharmadatu', the 'nondual state', or the 'absorption state'

- Dzogchen – the natural state, the Nyingma version of Mahamudra

- The Four Immeasurables, Metta

- Tantra techniques

Related Buddhist practices:

- Mindfulness – awareness in the present moment

- Mindfulness (psychology) – Western applications of Buddhist ideas

- Satipatthana

- chanting and mantra

Proper floor-sitting postures and supports while meditating:

- Floor sitting: cross-legged (full lotus, half lotus, Burmese) or seiza

- Cushions: zafu, zabuton

Traditional Buddhist texts on meditation:

- Anapanasati Sutta

- Satipatthana Sutta

- Buddhaghosa's Visuddhimagga – 'The path of Purification', used in Theravada Buddhism

- Kamalashila's Bhāvanākrama – 'Stages of meditation', used in Tibetan Buddhism

- Zhiyi's Great Concentration and Insight (Mohe Zhiguan) – used in the Chinese Tiantai school

- Seventeen tantras – Major Tibetan Dzogchen texts

- The Wangchuk Dorje's "Ocean of Definitive Meaning", major text on Mahamudra meditation.

- Dakpo Tashi Namgyal's "Mahamudra: The Moonlight – Quintessence of Mind and Meditation"

- Fukan-zazengi – By Dogen, used in the Japanese Soto Zen school

Traditional preliminary practices to Buddhist meditation:

- prostrations (also see Ngondro)

- refuge in the Triple Gem

- Five Precepts

Analog in Vedas:

Analog in Taoism:

Notes

- ↑ For instance, Kamalashila (2003), p. 4, states that Buddhist meditation "includes any method of meditation that has Enlightenment as its ultimate aim." Likewise, Bodhi (1999) writes: "To arrive at the experiential realization of the truths it is necessary to take up the practice of meditation.... At the climax of such contemplation the mental eye ... shifts its focus to the unconditioned state, Nibbana...." A similar although in some ways slightly broader definition is provided by Fischer-Schreiber et al. (1991), p. 142: "Meditation – general term for a multitude of religious practices, often quite different in method, but all having the same goal: to bring the consciousness of the practitioner to a state in which he can come to an experience of 'awakening,' 'liberation,' 'enlightenment.'" Kamalashila (2003) further allows that some Buddhist meditations are "of a more preparatory nature" (p. 4).

- ↑ The Pali and Sanskrit word bhāvanā literally means "development" as in "mental development." For the association of this term with "meditation," see Epstein (1995), p. 105; and, Fischer-Schreiber et al. (1991), p. 20. As an example from a well-known discourse of the Pāli Canon, in "The Greater Exhortation to Rahula" (Maha-Rahulovada Sutta, MN 62), Sariputta tells Rahula (in Pali, based on VRI, n.d.): ānāp ānassatiṃ, rāhula, bhāvanaṃ bhāvehi. Thanissaro (2006) translates this as: "Rahula, develop the meditation [bhāvana] of mindfulness of in-&-out breathing." (Square-bracketed Pali word included based on Thanissaro, 2006, end note.)

- ↑ See, for example, Rhys Davids & Stede (1921-25), entry for "jhāna1"; Thanissaro (1997); as well as, Kapleau (1989), p. 385, for the derivation of the word "zen" from Sanskrit "dhyāna." PTS Secretary Dr. Rupert Gethin, in describing the activities of wandering ascetics contemporaneous with the Buddha, wrote:

[T]here is the cultivation of meditative and contemplative techniques aimed at producing what might, for the lack of a suitable technical term in English, be referred to as 'altered states of consciousness'. In the technical vocabulary of Indian religious texts, such states come to be termed 'meditations' (Sanskrit: dhyāna, Pali: jhāna) or 'concentrations' (samādhi); the attainment of such states of consciousness was generally regarded as bringing the practitioner to deeper knowledge and experience of the nature of the world." (Gethin, 1998, p. 10.)

- ↑ Goldstein (2003) writes that, in regard to the Satipatthana Sutta, "there are more than fifty different practices outlined in this Sutta. The meditations that derive from these foundations of mindfulness are called vipassana..., and in one form or another – and by whatever name – are found in all the major Buddhist traditions" (p. 92). The forty concentrative meditation subjects refer to Visuddhimagga's oft-referenced enumeration. Regarding Tibetan visualizations, Kamalashila (2003), writes: "The Tara meditation ... is one example out of thousands of subjects for visualization meditation, each one arising out of some meditator's visionary experience of enlightened qualities, seen in the form of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas" (p. 227).

- ↑ Examples of contemporary school-specific "classics" include, from the Theravada tradition, Nyanaponika (1996) and, from the Zen tradition, Kapleau (1989).

- ↑ According to Frauwallner, mindfulness was a means to prevent the arising of craving, which resulted simply from contact between the senses and their objects. According to Frauwallner, this may have been the Buddha’s original idea.[2]

- ↑ For instance, from the Pāli Canon, see MN 44 (Thanissaro, 1998a) and AN 3:88 (Thanissaro, 1998b).

- ↑ For example, Bodhi (1999), in discussing a latter stage of developing Right View (that of "penetrating" the Four Noble Truths), states: "To arrive at the experiential realization of the truths it is necessary to take up the practice of meditation – first to strengthen the capacity for sustained concentration, then to develop insight."

- ↑ See also Samadhanga Sutta: The Factors of Concentration

- ↑ Gombrich: "I know this is controversial, but it seems to me that the third and fourth jhanas are thus quite unlike the second."[21]

- ↑ Wynne: "Thus the expression sato sampajāno in the third jhāna must denote a state of awareness different from the meditative absorption of the second jhāna (cetaso ekodibhāva). It suggests that the subject is doing something different from remaining in a meditative state, i.e., that he has come out of his absorption and is now once again aware of objects. The same is true of the word upek(k)hā: it does not denote an abstract 'equanimity', [but] it means to be aware of something and indifferent to it [...] The third and fourth jhāna-s, as it seems to me, describe the process of directing states of meditative absorption towards the mindful awareness of objects.[24]

- ↑ According to Gombrich, "the later tradition has falsified the jhana by classifying them as the quintessence of the concentrated, calming kind of meditation, ignoring the other - and indeed higher - element.[21]

- ↑ These definitions of samatha and vipassana are based on the "Four Kinds of Persons Sutta" (AN 4.94). This article's text is primarily based on Bodhi (2005), pp. 269-70, 440 n. 13. See also Thanissaro (1998d).

- ↑ See Thanissaro (1997) where for instance he underlines: "When [the Pali discourses] depict the Buddha telling his disciples to go meditate, they never quote him as saying 'go do vipassana,' but always 'go do jhana.' And they never equate the word vipassana with any mindfulness techniques. In the few instances where they do mention vipassana, they almost always pair it with samatha – not as two alternative methods, but as two qualities of mind that a person may 'gain' or 'be endowed with,' and that should be developed together."

Similarly, referencing MN 151, vv. 13–19, and AN IV, 125-27, Ajahn Brahm (who, like Bhikkhu Thanissaro, is of the Thai Forest Tradition) writes: "Some traditions speak of two types of meditation, insight meditation (vipassana) and calm meditation (samatha). In fact, the two are indivisible facets of the same process. Calm is the peaceful happiness born of meditation; insight is the clear understanding born of the same meditation. Calm leads to insight and insight leads to calm." (Brahm, 2006, p. 25.) - ↑ Bodhi (2000), pp. 1251-53. See also Thanissaro (1998c) (where this sutta is identified as SN 35.204). See also, for instance, a discourse (Pali: sutta) entitled, "Serenity and Insight" (SN 43.2), where the Buddha states: "And what, bhikkhus, is the path leading to the unconditioned? Serenity and insight...." (Bodhi, 2000, pp. 1372-73).

- ↑ Michael Carrithers, The Buddha, 1983, pages 33-34. Found in Founders of Faith, Oxford University Press, 1986. The author is referring to Pali literature. See however B. Alan Wallace, The bridge of quiescence: experiencing Tibetan Buddhist meditation. Carus Publishing Company, 1998, where the author demonstrates similar approaches to analyzing meditation within the Indo-Tibetan and Theravada traditions.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Bronkhorst 1993.

- 1 2 Williams 2000, p. 45.

- 1 2 3 4 Wynne 2007.

- ↑ Vetter 1988, p. XXXV-XXXVI.

- ↑ Gombrich 1997.

- ↑ See, for instance, Bodhi (1999).

- ↑ Dharmacarini Manishini/Alice Collett Kamma in Context: The Mahakammavibhangasutta and the Culakammavibhangasutta, Western Buddhist Review Volume 4

- ↑ Anālayo, Early Buddhist Meditation Studies, 2017, p. 165.

- ↑ Wynne, Alexander, The origin of Buddhist meditation, pp. 23, 37

- ↑ Bronkhorst, Johannes, The two traditions of meditation in Ancient India, Second edition: Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. 1993. (Reprint: 2000), p. 10.

- 1 2 Bronkhorst, Johannes. Early Buddhist Meditation. (paper presented at the conference “Buddhist Meditation from Ancient India to Modern Asia”, Jogye Order International Conference Hall, Seoul, 29 November 2012.)

- ↑ Bronkhorst 2012.

- ↑ Wynne, Alexander, The origin of Buddhist meditation, pp. 94-95

- ↑ Wynne, Alexander, The origin of Buddhist meditation, pp. 95

- 1 2 Bronkhorst 2012, p. 2.

- ↑ Bronkhorst 2012, p. 4.

- ↑ Vetter, Tilmann (1988), The Ideas and Meditative Practices of Early Buddhism, BRILL

- ↑ Bronkhorst, Johannes (1993), The Two Traditions Of Meditation In Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass Publ.

- ↑ Anālayo, Early Buddhist Meditation Studies, Barre Center for Buddhist Studies Barre, Massachusetts USA 2017, p 109

- ↑ "Ariyapariyesana Sutta, The Noble Search".

- 1 2 3 Wynne 2007, p. 140, note 58.

- ↑ Original publication: Gombrich, Richard (2007), Religious Experience in Early Buddhism, OCHS Library

- 1 2 3 Wynne 2007, p. 106.

- ↑ Wynne 2007, p. 106-107.

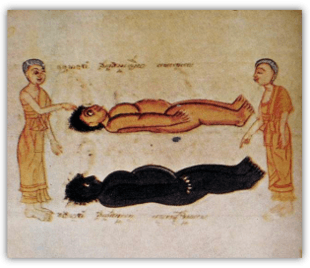

- ↑ from Teaching Dhamma by pictures: Explanation of a Siamese Traditional Buddhist Manuscript

- ↑ Bhikkhu Sujato, A History of Mindfulness How insight worsted tranquillity in the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta, Santipada, p. 148.

- ↑ Bhikkhu Sujato, A History of Mindfulness How insight worsted tranquillity in the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta, Santipada, p. 148.

- ↑ For instance, see Solé-Leris (1986), p. 75; and, Goldstein (2003), p. 92.

- ↑ See, for instance, Bodhi (1999) and Nyanaponika (1996), p. 108.

- ↑ See, for instance, AN 2.30 in Bodhi (2005), pp. 267-68, and Thanissaro (1998e).

- ↑ Bodhi (2005), pp. 268, 439 nn. 7, 9, 10. See also Thanissaro (1998f).

- ↑ Anālayo, Early Buddhist Meditation Studies, Barre Center for Buddhist Studies Barre, Massachusetts USA 2017, p 112, 115

- ↑ Anālayo, Early Buddhist Meditation Studies, Barre Center for Buddhist Studies Barre, Massachusetts USA 2017, p 117

- ↑ Edward Fitzpatrick Crangle, The Origin and Development of Early Indian Contemplative Practices, 1994, p 238

- ↑ “Should We Come Out of jhāna to Practice vipassanā?”, in Buddhist Studies in Honour of Venerable Kirindigalle Dhammaratana, S. Ratnayaka (ed.), 41–74, Colombo: Felicitation Committee. 2007

- ↑ Shankman, Richard 2008: The Experience of samādhi, An Indepth Exploration of Buddhist Meditation, Boston: Shambala

- ↑ Anālayo, Early Buddhist Meditation Studies, Barre Center for Buddhist Studies Barre, Massachusetts USA 2017, p 123

- ↑ Schmithausen 1981.

- ↑ Vetter 1988, p. 5-6.

- 1 2 Vetter 1988.

- ↑ vetter 1988, p. 5-6.

- ↑ Vetter 1988, p. xxxiv–xxxvii.

- ↑ Gombrich 1997, p. 131.

- ↑ Gombrich 1997, p. 96-134.

- ↑ Vetter 1988, p. xxxv.

- ↑ Anālayo, Early Buddhist Meditation Studies, Barre Center for Buddhist Studies Barre, Massachusetts USA 2017, p 185.

- 1 2 3 4 Merv Fowler (1999). Buddhism: Beliefs and Practices. Sussex Academic Press. pp. 60–62. ISBN 978-1-898723-66-0.

- 1 2 3 Peter Harvey (2012). An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices. Cambridge University Press. pp. 154, 326. ISBN 978-1-139-85126-8.

- ↑ Anālayo, Early Buddhist Meditation Studies, Barre Center for Buddhist Studies Barre, Massachusetts USA 2017, p 186.

- ↑ Anālayo, Early Buddhist Meditation Studies, Barre Center for Buddhist Studies Barre, Massachusetts USA 2017, p 194.

- ↑ PV Bapat. Vimuttimagga & Visuddhimagga – A Comparative Study, lv

- ↑ Sarah Shaw, Buddhist meditation: an anthology of texts from the Pāli canon. Routledge, 2006, pages 6-8. A Jataka tale gives a list of 38 of them. .

- ↑ PV Bapat. Vimuttimagga & Visuddhimagga – A Comparative Study, lvii

- ↑ Buddhaghosa & Nanamoli (1999), pp. 85, 90.

- ↑ Buddhaghoṣa & Nanamoli (1999), p. 110.

- ↑ Regarding the jhanic attainments that are possible with different meditation techniques, see Gunaratana (1988).

- ↑ Crosby, Kate (2013). Theravada Buddhism: Continuity, Diversity, and Identity. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118323298

- ↑ Tiyavanich K. Forest Recollections: Wandering Monks in Twentieth-Century Thailand. University of Hawaii Press, 1997.

- ↑ Newell, Catherine. Two Meditation Traditions from Contemporary Thailand: A Summary Overview, Rian Thai : International Journal of Thai Studies Vol. 4/2011

- ↑ Newell, Catherine. Two Meditation Traditions from Contemporary Thailand: A Summary Overview, Rian Thai : International Journal of Thai Studies Vol. 4/2011

- ↑ Newell, Catherine. Two Meditation Traditions from Contemporary Thailand: A Summary Overview, Rian Thai : International Journal of Thai Studies Vol. 4/2011

- ↑ Suen, Stephen, Methods of spiritual praxis in the Sarvāstivāda: A Study Primarily Based on the Abhidharma-mahāvibhāṣā, The University of Hong Kong 2009, p. 67.

- 1 2 Bhikkhu KL Dhammajoti, Sarvāstivāda-Abhidharma, Centre of Buddhist Studies The University of Hong Kong 2007, p 575-576.

- ↑ Suen, Stephen, Methods of spiritual praxis in the Sarvāstivāda: A Study Primarily Based on the Abhidharma-mahāvibhāṣā, The University of Hong Kong 2009, p. 177.

- ↑ Suen, Stephen, Methods of spiritual praxis in the Sarvāstivāda: A Study Primarily Based on the Abhidharma-mahāvibhāṣā, The University of Hong Kong 2009, p. 191.

- ↑ Bhikkhu KL Dhammajoti, Sarvāstivāda-Abhidharma, Centre of Buddhist Studies The University of Hong Kong 2007, p 576

- 1 2 Bhikkhu KL Dhammajoti, Sarvāstivāda-Abhidharma, Centre of Buddhist Studies The University of Hong Kong 2007, p 577.

- ↑ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 11

- ↑ Nan, Huai-Chin. To Realize Enlightenment: Practice of the Cultivation Path. 1994. p. 1

- ↑ Delenau, Florin, Buddhist Meditation in the Bodhisattvabhumi, 2013

- ↑ Deleanu, Florin (1992); Mindfulness of Breathing in the Dhyāna Sūtras. Transactions of the International Conference of Orientalists in Japan (TICOJ) 37, 42-57.

- ↑ Bhante Dhammadipa, KUMĀRAJĪVA’S MEDITATIVE LEGACY IN CHINA, 2015.

- ↑ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 83

- ↑ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 83

- ↑ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 84

- ↑ Yuan, Margaret. Grass Mountain: A Seven Day Intensive in Ch'an Training with Master Nan Huai-Chin. 1986. p. 55

- ↑ Yuan, Margaret. Grass Mountain: A Seven Day Intensive in Ch'an Training with Master Nan Huai-Chin. 1986. p. 55

- ↑ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 84

- ↑ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 84

- ↑ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 85

- ↑ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 44

- ↑ Nan, Huai-Chin. Basic Buddhism: Exploring Buddhism and Zen. 1997. p. 92

- ↑ Yuan, Margaret. Grass Mountain: A Seven Day Intensive in Ch'an Training with Master Nan Huai-Chin. 1986. p. 2

- ↑ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 45

- ↑ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 45

- ↑ Hsuan Hua. The Chan Handbook. 2004. p. 47

- ↑ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 49

- ↑ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 48

- ↑ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 110

- ↑ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 110

- ↑ Wu, Rujun (1993). T'ien-t'ai Buddhism and Early Mādhyamika. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1561-5.

- ↑ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 111

- ↑ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 125

- ↑ Abe, Ryūichi (2013). The Weaving of Mantra: Kūkai and the Construction of Esoteric Buddhist Discourse. Columbia University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-231-52887-0.

- ↑ Power, John; Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism, page 271

- ↑ Garson, Nathaniel DeWitt; Penetrating the Secret Essence Tantra: Context and Philosophy in the Mahayoga System of rNying-ma Tantra, 2004, p. 37

- ↑ See, for instance, Zongmi's description of bonpu and gedō zen, described further below.

- ↑ MARC UCLA

- ↑ Hutcherson, Cendri (2008-05-19). "Loving-Kindness Meditation Increases Social Connectedness" (PDF). doi:10.1037/a0013237.

- ↑ Brahmana, Metteyya (2008-05-19). "New Equanimity Meditation and Tools from Psychology to Test Its Effectiveness". doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.3810.1365.

- ↑ Iddhipada-vibhanga Sutta

- ↑ Samaññaphala Sutta

- ↑ Kevatta Sutta

Sources

- Bronkhorst, Johannes (2012), Early Buddhist Meditation. (paper presented at the conference “Buddhist Meditation from Ancient India to Modern Asia”, Jogye Order International Conference Hall, Seoul, 29 November 2012

- Gombrich, Richard F. (1997), How Buddhism Began, Munshiram Manoharlal

- Schmithausen, Lambert (1981), On some Aspects of Descriptions or Theories of 'Liberating Insight' and 'Enlightenment' in Early Buddhism". In: Studien zum Jainismus und Buddhismus (Gedenkschrift für Ludwig Alsdorf), hrsg. von Klaus Bruhn und Albrecht Wezler, Wiesbaden 1981, 199–250

- Vetter, Tilmann (1988), The Ideas and Meditative Practices of Early Buddhism, BRILL

- Wynne, Alexander (2007), The Origin of Buddhist Meditation, Routledge

Further reading

- Theravada

- Buddhaghosa, Bhadantacariya & Bhikkhu Nanamoli (trans.) (1999), The Path of Purification: Visuddhimagga. Seattle: BPS Pariyatti Editions. ISBN 1-928706-00-2.

- Bodhi, Bhikkhu (1999). The Noble Eightfold Path: The Way to the End of Suffering. Available on-line at http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/bodhi/waytoend.html.

- Bodhi, Bhikkhu (trans.) (2000). The Connected Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Samyutta Nikaya. Boston: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-331-1.

- Bodhi, Bhikkhu (ed.) (2005). In the Buddha's Words: An Anthology of Discourses from the Pāli Canon. Boston: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-491-1.

- Brahm, Ajahn (2006). Mindfulness, Bliss, and Beyond: A Meditator's Handbook. Somerville, MA: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-275-7.

- Hart, William (1987). The Art of Living: Vipassana Meditation: As Taught by S.N. Goenka. HarperOne. ISBN 0-06-063724-2

- Gunaratana, Henepola (1988). The Jhanas in Theravada Buddhist Meditation (Wheel No. 351/353). Kandy, Sri Lanka: Buddhist Publication Society. ISBN 955-24-0035-X. Retrieved 2008-07-21 from "Access to Insight" at http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/gunaratana/wheel351.html.

- Nyanaponika Thera (1996). The Heart of Buddhist Meditation. York Beach, ME: Samuel Weiser, Inc. ISBN 0-87728-073-8.

- Olendzki, Andrew (trans.) (2005). Sedaka Sutta: The Bamboo Acrobat (SN 47.19). Available at http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/sn/sn47/sn47.019.olen.html.

- Solé-Leris, Amadeo (1986). Tranquillity & Insight: An Introduction to the Oldest Form of Buddhist Meditation. Boston: Shambhala. ISBN 0-87773-385-6.

- Thanissaro Bhikkhu (1997). One Tool Among Many: The Place of Vipassana in Buddhist Practice. Available on-line at http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/thanissaro/onetool.html.

- Thanissaro Bhikkhu (trans.) (1998a). Culavedalla Sutta: The Shorter Set of Questions-and-Answers (MN 44). Retrieved 2007-06-22 from "Access to Insight" at http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/mn/mn.044.than.html.

- Thanissaro Bhikkhu (trans.) (1998b). Sikkha Sutta: Trainings (1) (AN 3:38). Retrieved 2007-06-22 from "Access to Insight" at http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/an/an03/an03.088.than.html.

- Thanissaro Bhikkhu (trans.) (1998c). Kimsuka Sutta: The Riddle Tree (SN 35.204). Available on-line at http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/sn/sn35/sn35.204.than.html.

- Thanissaro Bhikkhu (trans.) (1998d). Samadhi Sutta: Concentration (Tranquillity and Insight) (AN 4.94). Available on-line at http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/an/an04/an04.094.than.html.

- Thanissaro Bhikkhu (trans.) (1998e). Vijja-bhagiya Sutta: A Share in Clear Knowing (AN 2.30). Available on-line at http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/an/an02/an02.030.than.html.

- Thanissaro Bhikkhu (trans.) (1998f). Yuganaddha Sutta: In Tandem (AN 4.170). Available on-line at http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/an/an04/an04.170.than.html.

- Thanissaro Bhikkhu (trans.) (2006). Maha-Rahulovada Sutta: The Greater Exhortation to Rahula (MN 62). Retrieved 2007-11-07 from "Access to Insight" at http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/mn/mn.062.than.html.

- Vipassana Research Institute (VRI) (n.d.). Bhikkhuvaggo (second chapter of the second volume of the Majjhima Nikaya). Retrieved 2007-11-07 from VRI at http://www.tipitaka.org/romn/cscd/s0202m.mul1.xml.

- Zen

- Kapleau, Phillip (1989). The Three Pillars of Zen: Teaching, Practice and Enlightenment. NY: Anchor Books. ISBN 0-385-26093-8.

- Tibetan Buddhism

- Mipham, Sakyong (2003). Turning the Mind into an Ally. NY: Riverhead Books. ISBN 1-57322-206-2.

- Sogyal Rinpoche, The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying, ISBN 0-06-250834-2

- Mindfulness

- Kabat-Zinn, Jon (2001). Full Catastrophe Living. NY: Dell Publishing. ISBN 0-385-30312-2.

- Linehan, Marsha (1993). Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. NY: Guilford Press. ISBN 0-89862-183-6.

- Buddhist modernism

- Epstein, Mark (1995). Thoughts Without a Thinker: Psychotherapy from a Buddhist Perspective. BasicBooks. ISBN 0-465-03931-6 (cloth). ISBN 0-465-08585-7 (paper).

- Goldstein, Joseph (2003). One Dharma: The Emerging Western Buddhism. NY: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 0-06-251701-5.

- Scholarly

- Rhys Davids, T.W. & William Stede (eds.) (1921-5). The Pali Text Society’s Pali–English Dictionary. Chipstead: Pali Text Society. A general on-line search engine for the PED is available at http://dsal.uchicago.edu/dictionaries/pali/.

- Fischer-Schreiber, Ingrid, Franz-Karl Ehrhard, Michael S. Diener & Michael H. Kohn (trans.) (1991). The Shambhala Dictionary of Buddhism and Zen. Boston: Shambhala. ISBN 0-87773-520-4 (French ed.: Monique Thiollet (trans.) (1989). Dictionnaire de la Sagesse Orientale. Paris: Robert Laffont. ISBN 2-221-05611-6.)

- Gethin, Rupert (1998). The Foundations of Buddhism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-289223-1.

External links

- Guided Meditations on the Lamrim – The Gradual Path to Enlightenment by Bhikshuni Thubten Chodron (PDF file)