Austronesian peoples

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 400 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| |

| Languages | |

| Austronesian languages | |

| Religion | |

| Animism, Buddhism, Christianity (Roman Catholicism, Protestantism), Folk religion, Hinduism (Balinese Hinduism), Indigenous religion, Islam, Shamanism |

The Austronesian peoples[14] are various groups in Southeast Asia, Oceania and East Africa that speak languages belonging to the Austronesian language family. They include Taiwanese aborigines, the majority of ethnic groups in the Philippines, East Timor, Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei, Cocos (Keeling) Islands, Polynesia, Micronesia and Madagascar, as well as the Malays of Singapore, the Polynesians of New Zealand and Hawaii and the non-Papuan peoples of Melanesia. All of these peoples can be connected through the Austronesian language family. They are also found in the regions of Southern Thailand, the Cham areas in Vietnam and Cambodia, and the Hainan island province of China, parts of Sri Lanka, southern Myanmar, the southern tip of South Africa, Suriname, and some of the Andaman Islands. On top of that, modern-era migration brought Austronesian-speaking people to the United States, Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Spain, Portugal, Hong Kong, Macau and Mauritius, as well as the West Asian countries. The people of the Maldives also possess traces of genes associated with Austronesian-speaking peoples via gene flow from the Malay Archipelago.[15] The nations and territories predominantly populated by Austronesian-speaking peoples are known collectively as Austronesia.

Prehistory and history

.jpg)

Archaeological evidence demonstrates a technological connection between the farming cultures of the "south", meaning Southeast Asia and Melanesia, and sites that are first known from mainland China; whereas a combination of archaeological and linguistic evidence has been interpreted as supporting a "northern" origin for the Austronesian language family in mainland southern China and Taiwan.

It is theoretically possible that a few thousand years before the southward expansion of the Han dynasty that Austronesian speakers spread down the coast of southern China past Taiwan as far as the Gulf of Tonkin. In time, the spread of other language groups such as Austroasiatic, Tai-Kadai, Hmong-Mien and Sino-Tibetan (such as Chinese) led to the assimilation and eventual sinicization of all (proto) Austronesian-speaking populations that remained on the mainland (a process which continues today in Taiwan).[16] In a recent treatment, all Austronesian languages were classified into 10 subfamilies, with all the extra-Formosan languages grouped in one subfamily and with representatives of the remaining nine known only in Taiwan.[17] It has been argued that these patterns are best explained by dispersal of an agricultural people from Taiwan into insular Southeast Asia, Melanesia, and, ultimately, the remote Pacific. This model has been termed the "express train to Polynesia"[18][19]— it is broadly consistent with available data [20], despite concerns that have been raised.[21]

Alternatives to this model posit an indigenous origin for the Austronesian languages in Southeast Asia or Melanesia.[22][23][24][25]

Genetic analyses suggest that the Southeast Asian Austronesians had spread over Sundaland (the land mass of Southeastern Asia before rising sea-level created the archipelago of Southeast Asia) and evolved in situ over the last 35,000 years.[26] Nevertheless, in 2016, DNA analysis carried out found that one of the genetic markers used in the study but not the others supports a small-scale "out-of-Taiwan" hypothesis.[27] The studies suggest that only a small fraction of the Taiwan genetic lineages are found among the people of South East Asia, and it is argued that these movements of people from Taiwan, while smaller in scale, had a strong impact on the culture and language of the people.[28][29][30]

Migration and dispersion

Genomic analysis of cultivated coconut (Cocos nucifera) has shed light on the movements of Austronesian peoples. By examining 10 microsatelite loci, researchers found that there are 2 genetically distinct subpopulations of coconut – one originating in the Indian Ocean, the other in the Pacific Ocean. However, there is evidence of admixture, the transfer of genetic material, between the two populations. Given that coconuts are ideally suited for ocean dispersal, it seems possible that individuals from one population could have floated to the other. However, the locations of the admixture events are limited to Madagascar and coastal east Africa and exclude the Seychelles and Mauritius. Sailing west from Maritime Southeast Asia in the Indian Ocean, the Austronesian peoples reached Madagascar by ca. 50–500 CE, and reached other parts thereafter. This forms a pattern that coincides with the known trade routes of Austronesian sailors. Additionally, there is a genetically distinct sub-population of coconuts on the eastern coast of South America which has undergone a genetic bottleneck resulting from a founder effect; however, its ancestral population is the pacific coconut, which suggests that Austronesian peoples may have sailed as far east as the Americas.[31][32][33]

"Out of Taiwan" model

An element in the ancestry of Austronesian-speaking peoples, the one which carried their ancestral language, originated on the island of Taiwan. This occurred after the migration of pre-Austronesian-speaking peoples from continental Asia between approximately 10,000–6,000 BCE.[34][17] Other research has suggested that, according to radiocarbon dates, Austronesians may have migrated from mainland China to Taiwan as late as 4000 BC (Dapenkeng culture).[35] Before migrating to Taiwan, Austronesian speakers originated from the Neolithic cultures of Southeastern China, such as the Hemudu culture or the Liangzhu culture of the Yangtze River Delta.[36][37][38]

Based on recent archaeological evidence as well as linguistic evidence, Roger Blench (2014)[39] considers the Austronesians in Taiwan to have been a melting pot of immigrants from various parts of the coast of eastern China that had been migrating to Taiwan by 4,000 B.P. These immigrants included people from the foxtail millet-cultivating Longshan culture of Shandong (with Longshan-type cultures found in southern Taiwan), the fishing-based Dapenkeng culture of coastal Fujian, and the Yuanshan culture of northernmost Taiwan which Blench suggests may have originated from the coast of Guangdong. Based on geography and cultural vocabulary, Blench believes that the Yuanshan people may have spoken Northeast Formosan languages. Thus, Blench believes that there is in fact no "apical" ancestor of Austronesian in the sense that there was no true single Proto-Austronesian language that gave rise to present-day Austronesian languages. Instead, multiple migrations of various pre-Austronesian peoples and languages from the Chinese mainland that were related but distinct came together to form what we now know as Austronesian in Taiwan. Hence, Blench considers the single-migration model to be inconsistent with both the archaeological and linguistic (lexical) evidence.

Tianlong Jiao (2007)[40] notes that Neolithic peoples from the coast of southeastern China migrated to Taiwan from 6,500-5,000 B.P. The Neolithic period in southeastern China lasted from 6,500 B.P. until 3,500 B.P., and can be divided into the early (ca, 6500-5000 B.P.), middle (ca. 5000-4300 B.P.), and late (ca. 4300-3500 B.P.) Neolithic periods. The Neolithic in southeastern China started off with pottery, polished stone tools, and bone tools, with technology continuing to progress over the years. Neolithic peoples in Taiwan and mainland China continued to maintain regular contact with each other until 3,500 B.P., which was when bronze artefacts started to appear. Jiao (2013)[41] notes the Neolithic appeared on the coast of Fujian around 6,000 B.P. During the Neolithic, the coast of Fujian had a low population density, with the population depending on mostly on fishing and hunting, alongside with limited agriculture.

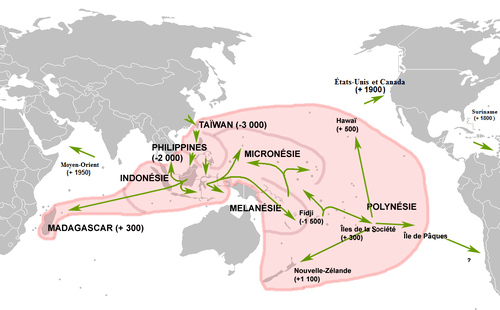

According to the mainstream "out-of-Taiwan model", a large-scale Austronesian expansion began around 3000–1500 BCE. Population growth primarily fuelled this migration. These first settlers may have landed in northern Luzon in the archipelago of the Philippines, intermingling with the earlier Australo-Melanesian population who had inhabited the islands since about 23,000 years earlier. Over the next thousand years, Austronesian peoples migrated southeast to the rest of the Philippines, and into the islands of the Celebes Sea, Borneo, and Indonesia. The Austronesian peoples of Maritime Southeast Asia sailed eastward, and spread to the islands of Melanesia and Micronesia between 1200 BCE and 500 CE, respectively. The Austronesian inhabitants that spread westward through Maritime Southeast Asia had reached some parts of mainland Southeast Asia, and later on Madagascar.[34][42]

Sailing to Micronesia and the previously uninhabited islands of remote Oceania by 1000 BCE, the Austronesian peoples founded Polynesia.[43] These people settled most of the Pacific Islands. They had settled Rapa Nui (Easter Island) by AD 300, Hawaii by AD 400, and into New Zealand by about 1280 CE. There is evidence, based in the spreading of the sweet potato, that they reached South America where they traded with the Native Americans.[44][45]

In the Indian Ocean they sailed west from Maritime Southeast Asia; the Austronesian peoples reached Madagascar by ca. 50–500 CE.[32][33]

"Southeast Asian origin" model

This "out of Taiwan model" has been challenged by a 2008 study. Examination of mitochondrial DNA lineages shows that they have been evolving within Island Southeast Asia (ISEA) for a longer period than previously believed. Population dispersals occurred at the same time as sea levels rose, which may have resulted in migrations to the Philippines as far north as Taiwan within the last 10,000 years.[26] The migrations were likely driven by climate change — the effects of the drowning the Sundaland subcontinent (which had extended the Asian landmass as far as Borneo and Java). This happened during the period 15,000 to 7,000 years ago following the Last Glacial Maximum. Rising sea levels in three massive pulses caused flooding and the partial submergence of the Sunda subcontinent, creating the Java and South China Seas and the thousands of islands that make up Indonesia and the Philippines today.[24] Genetic evidence found in 2016 indicates that movements of people from Taiwan to the islands of South East Asia did occur, albeit smaller in scale, which nevertheless may have brought about linguistic and cultural changes.[27]

Findings from HUGO (Human Genome Organization) in 2009 also show that Asia was populated primarily through a single migration event out of Africa whereby an early population first entered South East Asia before they moved northwards to East Asia.[46][47][48] They found genetic similarities between populations throughout Asia and an increase in genetic diversity from northern to southern latitudes. Although the Chinese population is very large, it has less variation than the smaller number of individuals living in South East Asia, because the Chinese expansion occurred very recently, following the development of rice agriculture — within only the last 10,000 years.

Formation of tribes and kingdoms

By the beginning of the first millennium CE, most of the Austronesian inhabitants in Maritime Southeast Asia began trading with India and China. The adoption of Hindu statecraft model allowed the creation of Indianized kingdoms such as Tarumanagara, Champa, Langkasuka, Melayu, Srivijaya, Medang Mataram, Majapahit, and Bali. Between the 5th to 15th century Hinduism and Buddhism were established as the main religion in the region.

Muslim traders from the Arabian peninsula were thought to have brought Islam by the 10th century. Islam was established as the dominant religion in the Indonesian archipelago by the 16th century. The Austronesian inhabitants of Polynesia were unaffected by this cultural trade, and retained their indigenous culture in the Pacific region.[49]

Kingdom of Larantuka in Flores, East Nusa Tenggara was the only Christian (Roman Catholic) indigenous kingdom in Indonesia and in Southeast Asia, with the first king named Lorenzo.[50]

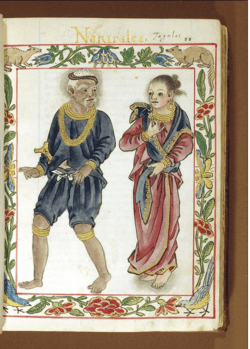

Western Europeans in search of spices and gold later colonized most of the Austronesian-speaking countries of the Asia-Pacific region, beginning from the 16th century with the Portuguese and Spanish colonization of some parts of Indonesia (present day East Timor), the Philippines, Palau, Guam, and the Mariana Islands; the Dutch colonization of the Indonesian archipelago; the British colonization of Malaysia and Oceania; the French colonization of French Polynesia; and later, the American governance of the Pacific.

Meanwhile, the British, Germans, French, Americans, and Japanese began establishing spheres of influence within the Pacific Islands during the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Japanese later invaded most of Southeast Asia and some parts of the Pacific during World War II. The latter half of the 20th century initiated independence of modern-day Indonesia, Malaysia, East Timor and many of the Pacific Island nations, as well as the re-independence of the Philippines.

Geographic distribution

.png)

Austronesian peoples consist of the following groupings by name and geographic location.

- Formosan: Taiwan. e.g. Amis, Atayal, Bunun, Paiwan.

- Malayo-Polynesian:

- Borneo groups: e.g. Kadazan-Dusun, Murut, Iban, Bidayuh, Dayak, Lun Bawang/Lundayeh

- Chamic group: Cambodia, Hainan, Cham areas of Vietnam (remnants of the Champa kingdom which covered central and southern Vietnam) as well as Aceh in northern Sumatra. e.g. Acehnese, Chams, Jarai, Utsuls.

- Central Luzon group: Kapampangan, Pangasinan, Sambal.

- Igorot (Cordillerans): Cordilleras. e.g. Balangao, Ibaloi, Ifugao, Itneg, Kankanaey.

- Lumad: Mindanao. e.g. Kamayo, Manobo, Tasaday, T'boli.

- Malagasy: Madagascar. e.g. Betsileo, Merina, Sakalava, Tsimihety.

- Melanesians: Melanesia. Fijians, e.g. Kanak, Ni-Vanuatu, Solomon Islands

- Micronesians: Micronesia. e.g. Carolinian, Chamorros, Palauan.

- Moken: Burma, Thailand.

- Moro: Bangsamoro (Mindanao & Sulu Archipelago). e.g. Maguindanao, Maranao, Tausug, Sama-Bajau.

- Northern Luzon lowlanders: e.g. Ilocano, Ibanag, Itawes.

- Polynesians: Polynesia. Māori, Native Hawaiians, Samoans.

- Southern Luzon lowlanders: e.g. Tagalog, Bicolano

- Sunda–Sulawesi language and ethnic groups including Malay, Sundanese, Javanese, Balinese, Batak (geographically Includes Malaysia, Brunei, Pattani, Singapore, Cocos (Keeling) Islands parts of Sri Lanka, southern Myanmar and much of western and central Indonesia).

- Visayans: Visayas. e.g. Aklanon, Boholano, Cebuano, Hiligaynon, Masbateño, Waray.

According to a recent studies by Stanford University, there is wide variety of paternal ancestry among the Austronesian people, aside from European introgression found in Maritime Southeast Asia, Oceania, and Madagascar. They constitute the dominant ethnic group in the Malay Peninsula, Maritime Southeast Asia, Melanesia, Micronesia, Polynesia and Madagascar. An estimated 380,000,000 people living in these regions are of Austronesian descent.

The peoples constitute the dominant ethnic groups in Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei, the Philippines, the southernmost part of Thailand and East Timor, together with Singapore. Outside this area, they inhabit Palau, Guam and the Northern Marianas, most of Madagascar, the Cham areas of Vietnam and Cambodia (the remnants of the Champa kingdom which covered central and southern Vietnam), and all countries in the Micronesian and Polynesian sphere of influence.

Culture

The native culture of Austronesia varies from region to region. The early Austronesian peoples considered the sea as the basic feature of their life. Following their diaspora to Southeast Asia and Oceania, they migrated by boat to other islands. Boats of different sizes and shapes have been found in every Austronesian culture, from Madagascar, Maritime Southeast Asia, to Polynesia, and have different names. In Southeast Asia, head-hunting was restricted to the highlands as a result of warfare. Mummification is only found among the highland Austronesian Filipinos, and in some Indonesian groups in Celebes and Borneo.

| Decimal numbers | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAN, circa 4000 BC | *isa | *DuSa | *telu | *Sepat | *lima | *enem | *pitu | *walu | *Siwa | *puluq |

| Tagalog | isá | dalawá | tatló | ápat | limá | ánim | pitó | waló | siyám | sampu |

| Kadazan | iso | duvo | tohu | apat | himo | onom | tu' | vahu | sizam | hopod |

| Dusun | iso | duwo | tolu | apat | limo | onom | tulu | walu | siyam | hopod |

| Lun Bawang/Lundayeh | aceh | due | telu | apat | lime | enam | tudu | walu | yiwa | puluh |

| Ilocano | maysá | dua | talló | uppát | limá | inném | pitó | waló | siam | sangapúlo |

| Cebuano | usá | duhá | tuló | upat | limá | unom | pitó | waló | siyám | napulu |

| Hiligaynon | isá | duhá | tatló | apat | limá | anum | pitó | waló | siyám | pulo |

| Chamorro | maisa/håcha | hugua | tulu | fatfat | lima | gunum | fiti | guålu | sigua | månot/fulu |

| Indonesian | satu/suatu[51] | dua | tiga[52][53] | empat | lima[54] | enam | tujuh | delapan[55] | sembilan | sepuluh |

| Malay | satu/sa | dua | tiga[56] | empat | lima | enam | tujuh | lapan | sembilan | sepuluh |

| Javanese | siji | loro | telu | papat | limo | nem | pitu | wolu | songo | sepuluh |

| Sundanese | hiji | dua | tilu | opat | lima | genep | tujuh | dalapan | salapan | sapuluh |

| Tetum | ida | rua | tolu | haat | lima | neen | hitu | ualu | sia | sanulu |

| Fijian | dua | rua | tolu | vā | lima | ono | vitu | walu | ciwa | tini |

| Tongan | taha | ua | tolu | fā | nima | ono | fitu | valu | hiva | -fulu |

| Sāmoan | tasi | lua | tolu | fā | lima | ono | fitu | valu | iva | sefulu |

| Māori | tahi | rua | toru | whā | rima | ono | whitu | waru | iwa | tekau (archaic: ngahuru) |

| Tahitian | hō'ē | piti | toru | maha | pae | ono | hitu | va'u | iva | 'ahuru |

| Marquesan | e tahi | e 'ua | e to'u | e fa | e 'ima | e ono | e fitu | e va'u | e iva | 'onohu'u |

| Hawaiian | kahi | lua | kolu | hā | lima | ono | hiku | walu | iwa | -'umi |

| Malagasy | iray/isa | roa | telo | efatra | dimy | enina | fito | valo | sivy | folo |

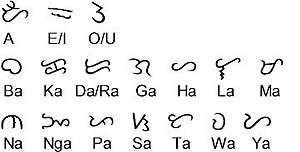

Writing

With the possible exception of rongorongo on Easter Island, writing among pre-modern Austronesians was limited to the Indianized states and the sultanates of Maritime Southeast Asia. These systems included abugidas from the Brahmic family, such as Baybayin, the Javanese script, and Old Kawi, and abjads derived from the Arabic script such as Jawi.

Since the 20th century, new scripts were mostly alphabets adapted from the Latin alphabet, as in the Hawaiian alphabet, Filipino alphabet, and Malay alphabet; however, several Formosan languages are written in zhuyin, and Cia-Cia off Sulawesi has experimented with hangul.

Arts

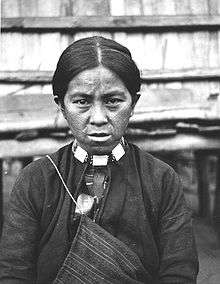

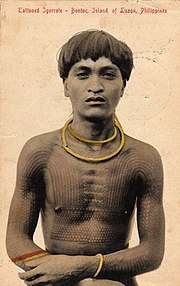

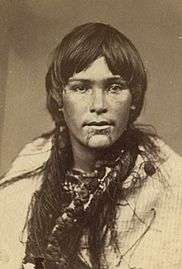

Right: A young Māori woman with traditional tattoos (moko) on the lips and chin (c. 1860–1879). These were symbols of status and rank, as well as being considered marks of beauty.

Body art among Austronesian peoples is common, especially elaborate tattooing which has ancient origins.[58] It is particularly prominent in Polynesian cultures, from where the word "tattoo" derives. But tattooing is also prominent among Austronesian groups in Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Malaysia.[59]

Among the Māori of New Zealand, tattoos (moko) were originally carved into the skin using bone chisels (uhi) rather than through puncturing as in usual practice.[60] In addition to being pigmented, the skin was also left raised into ridges of swirling patterns.[61]

In the Philippines, the Spanish called the Filipinos they first encountered in the Visayas as the Pintados, ("the painted ones" or "the tattooed ones")[62] due to their practice of tattooing their entire bodies.[63] Tattooing traditions were mostly lost as the natives of the islands converted to Christianity and Islam, though they were still practised in isolated groups in the highlands of Luzon and Mindanao. Philippine tattoos were usually geometric patterns or stylized depictions of animals, plants, and human figures.[64][65][66] Some of the few remaining traditional tattoos in the Philippines are from elders of the Igorot peoples. Most of these were records of war exploits against the Japanese during World War II.[67]

Decorated jars and other forms of pottery are also common, with patterns often resembling those used in tattoos. Austronesian peoples living close to mainland Asia were also influenced by Chinese, Indian, and Arabic art forms.

Architecture

Austronesian Vernacular Stilt house is the native cultural houses of Austronesian people. Every Austronesian country has their own name and style for their own Austronesian houses. In the Philippines these are called Bahay kubo with many styles and variants, in Indonesia these are called Rumah adat also with many variants, and in Malaysia these are called Rumah Melayu which are also found in Indonesia and part of the Rumah Adat family.

Religion

Indigenous religions were initially predominant. Mythologies vary by culture and geographical location, but are generally bound by the belief in an all-powerful divinity. Other beliefs such as ancestor worship, animism, and shamanism are also practiced. Currently, many of these beliefs have gradually been replaced. Examples of native religions include: Anito, Gabâ, Sunda Wiwitan, Kejawen, and the Māori religion. The moai of the Rapa Nui is another example since they are built to represent deceased ancestors.

Southeast Asian contact with India and China allowed the introduction of Hinduism and Buddhism. Later, Muslim traders introduced the Islamic faith between the periods of the 10th, and 13th century. The European Age of Discovery, brought Christianity to various parts of the region, including both New Zealand and Australia. Currently, the dominant religions are Christianity in the Philippines, much of eastern Indonesia, some parts of Indonesian Sumatra and Borneo, East Timor, Papua New Guinea, Singapore, most of the Pacific Islands, and Madagascar; Islam found in Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, southern Thailand, the southern Philippines and Brunei; Hinduism in Singapore, Bali, and some parts of Indonesia, Malaysia and Philippines. There is also a tiny population in Manado on the island of Sulawesi who professed Judaism, most of whom either have Jewish ancestry who later mixed with the indigenous Minahasans or are converts.

Music

The Austronesian music in Maritime Southeast Asia had a mixture of Chinese, Indian, and Arabic musical styles and sounds that had fused together with the indigenous Austronesian culture and music. In Indonesia, Gamelan, a type of orchestra that incorporates Xylophone and Metallophone elements, is widely used in its Hindu, Buddhist, and Islamic cultural tradition. In some parts of the southern, and northern Philippines, an Arabic gong-drum known as Kulintang, and a gong-chime known as Gangsa, is also used. The Austronesian music of Oceania have retained their indigenous Austronesian sounds. The Slit drums is an indigenous Austronesian musical instrument that were invented and used by the Southeast Asian-Austronesian, and Oceanic-Austronesian ethnic groups.

Genetic studies

Genetic studies have been done on the people and related groups.[68] The Haplogroup O1 (Y-DNA)a-M119 genetic marker is frequently detected in Native Taiwanese, northern Philippines and Polynesians, as well as some people in Indonesia, Malaysia and non-Austronesian populations in southern China.[69] A 2007 analysis of the DNA recovered from human remains in archeological sites of prehistoric peoples along the Yangtze River in China also shows high frequencies of Haplogroup O1 in the Neolithic Liangzhu culture, linking them to Austronesian and Tai-Kadai peoples. The Liangzhu culture existed in coastal areas around the mouth of the Yangtze. Haplogroup O1 was absent in other archeological sites inland. The authors of the study suggest that this may be evidence of two different human migration routes during the peopling of Eastern Asia; one coastal and the other inland, with little genetic flow between them.[70]

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) analysis in 2008 suggests that the populations in the islands of South East Asia may have evolved in situ over the last 35,000 years, that they had already established themselves in the region before the Neolithic period, long before the Taiwanese people were proposed to have moved out of Taiwan into the region.[26] Nevertheless, in 2016, DNA analysis carried out found that one of the genetic markers used in the study, haplogroup M7c3c, supports the "out-of-Taiwan" hypothesis, although not from the other genetic markers. Results from these studies suggest that there were movements of Neolithic people from Taiwan to the islands of South East Asia around 4,000 years ago, but they were small-scale affairs, with greater impact in the Philippines.[27] The fractions of Taiwanese Neolithic lineages present in the people of the islands of South East Asia today are estimated to range from 28% in the Philippines to 13.6% in Western Indonesia and 10.3% in Kalimantan.[71] The authors argue that the cultural impact on the people was due to small-scale interactions and waves of acculturation, and that the Taiwanese migrants despite being smaller in numbers had a strong influence on the culture and language of the people as they were seen as an elite or associated with a new religion or philosophy.[28][30] Some researchers have proposed a more complex pattern of settlement and dispersal, where the Austronesians were dispersed from mainland South East Asia via two routes: a northern route through Taiwan before they moved further down to the South East Asian islands, and a southern route through western Indonesia.[72] Others have also found genetic links between the ancestors of Austronesians and people of North and South China.[73][74]

The Austronesian speaking people can now be grouped into two genetically close groups:

- 1. The Sundanese-Malayan group consisting of Austronesians in Nusantara (Timor-Leste, Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei), Madagascar and historically Southeast Asian Mainland.

- 2. The Taiwanese-Polynesian group consisting of Austronesians in Taiwan, Batanes and Babuyan, Polynesia, Micronesia and historically South China.

See also

- Austronesian languages

- Pacific Islander

- Dayak

- Kadazan-Dusun

- Samoans

- Tongans

- Maori people

- Fijian people

- Cape Malays

- Native Hawaiians

- Native Indonesians

- Taiwanese Aborigines

- Malagasy people

- Ethnic Malays

- Minangkabau people

- Acehnese people

- Cham people

- Filipinos

- Javanese people

- Balinese people

- Sundanese people

- Moana (2016 film)

- Lun Bawang/Lundayeh

Notes

- ↑ http://www.bps.go.id/website/pdf_publikasi/watermark_Proyeksi%20Penduduk%20Indonesia%202010-2035.pdf

- ↑ "Population, total". Data. World Bank Group. 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ↑ "Malaysia". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 February 2013. Retrieved 2013-07-22.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 February 2016. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 February 2013. Retrieved 2013-07-22.

- ↑ http://www.stats.govt.nz/census/2006-census-data/national-highlights/2006-census-quickstats-national-highlights.htm?page=para025Master

- ↑ http://www.stats.govt.nz/NR/rdonlyres/62F419D4-5946-407A-9553-DA9E7A847622/0/09ethnicgroup.xls

- ↑ About 13.6% of Singaporeans are of Malay descent. In addition to these, many Chinese Singaporeans are also of mixed Austronesian descent. See also "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 July 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-25.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 April 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-23.

- ↑ "U.S. 2000 Census". Archived from the original on 18 November 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ↑ "Suriname". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ↑ "A2 : Population by ethnic group according to districts, 2012". Census of Population& Housing, 2011. Department of Census& Statistics, Sri Lanka.

- ↑ According to the anthropologist Wilhelm Solheim II: "I emphasize again, as I have done in many other articles, that 'Austronesian' is a linguistic term and is the name of a super language family. It should never be used as a name for a people, genetically speaking, or a culture. To refer to people who speak an Austronesian language the phrase 'Austronesian-speaking people' should be used." Origins of the Filipinos and Their Languages. (January 2006).

- ↑ Maloney, C. (1980). People of the Maldive Islands. Orient Longman Ltd, Madras. ISBN 0-86131-158-2.

- ↑ Goodenough, Ward Hunt (1996). Prehistoric Settlement of the Pacific, Volume 86, Part 5. ISBN 9780871698650.

- 1 2 Blust R (1999). "Subgrouping, circularity and extinction: some issues in Austronesian comparative linguistics". In Zeitoun E; Jen-kuei Li, P. Selected papers from the Eighth International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics. Taipei: Academia Sinica. pp. 31–94. ISBN 9576716322. OCLC 58527039.

- ↑ Diamond, Jared M. (1988). "Express train to Polynesia". Nature. 336 (6197): 307–8. Bibcode:1988Natur.336..307D. doi:10.1038/336307a0.

- ↑ Diamond 1998, pp. 336ff

- ↑ http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2016/10/game-changing-study-suggests-first-polynesians-voyaged-all-way-east-asia

- ↑ Richards, Martin; Oppenheimer, Stephen; Sykes, Bryan (1998). "mtDNA suggests Polynesian origins in Eastern Indonesia". American Journal of Human Genetics. 63 (4): 1234–6. doi:10.1086/302043. PMC 1377476. PMID 9758601.

- ↑ Dyen, Isidore (1962). "The lexicostatistical classification of Malayapolynesian languages". Language. 38 (1): 38–46. doi:10.2307/411187. JSTOR 411187.

- ↑ Isidore Dyen (1965). "A Lexicostatistical Classification of the Austronesian Languages". Internationald Journal of American Linguistics, Memoir. 19: 38–46.

- 1 2 Oppenheimer, Stephen (1998). Eden in the east: the drowned continent. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-81816-3.

- ↑ Cristian Capelli; James F. Wilson; Martin Richards; Michael P. H. Stumpf; Fiona Gratrix; Stephen Oppenheimer; Peter Underhill; Vincenzo L. Pascali; Tsang-Ming Ko & David B. Goldstein (2001). "A Predominantly Indigenous Paternal Heritage for the Austronesian-Speaking Peoples of Insular Southeast Asia and Oceania". American Journal of Human Genetics. 68 (2): 432–443. doi:10.1086/318205. PMC 1235276. PMID 11170891.

- 1 2 3 Soares P, Trejaut JA, Loo JH (June 2008). "Climate change and postglacial human dispersals in southeast Asia". Mol. Biol. Evol. 25 (6): 1209–18. doi:10.1093/molbev/msn068. PMID 18359946. "New DNA evidence overturns population migration theory in Island Southeast Asia". Phys.org. 23 May 2008.

- 1 2 3 Pedro A. Soares, Jean A. Trejaut, Teresa Rito, Bruno Cavadas, Catherine Hill, Ken Khong Eng, Maru MorminaAndreia Brandão, Ross M. Fraser, Tse-Yi Wang, Jun-Hun Loo, Christopher Snell, Tsang-Ming Ko, António Amorim, Maria Pala, Vincent Macaulay, David Bulbeck, James F. Wilson, Leonor Gusmão, Luísa Pereira, Stephen Oppenheimer, Marie Lin, Martin B. Richard (2016). "Resolving the ancestry of Austronesian-speaking populations". Human Genetics. doi:10.1007/s00439-015-1620-z. PMID 26781090.

- 1 2 "New research into the origins of the Austronesian languages: Complex genetic data now confirms that Mitochondrial DNA found in Pacific islanders was present in Island Southeast Asia at a much earlier period". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2017-08-24.

- ↑ Melton, T.; Clifford, S.; Martinson, J.; Batzer, M.; Stoneking, M. (December 1998). "Genetic evidence for the proto-Austronesian homeland in Asia: mtDNA and nuclear DNA variation in Taiwanese aboriginal tribes". American Journal of Human Genetics. 63 (6): 1807–1823. doi:10.1086/302131. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 1377653. PMID 9837834.

- 1 2 "DNA Analysis Gives Insight into Austronesian Languages". New Historian. 2016-02-01. Retrieved 2017-08-24.

- ↑ Gunn, Bee; Luc Baudouin; Kenneth M. Olsen (2011). "Independent Origins of Cultivated Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) in the Old World Tropics". PLoS ONE. 6 (6): e21143. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...621143G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021143. PMC 3120816. PMID 21731660.

- 1 2 Dewar, RE; Wright, HT (1993). "The culture history of Madagascar". Journal of World Prehistory. 7 (4): 417–466. doi:10.1007/BF00997802.

- 1 2 Burney DA, Burney LP, Godfrey LR, Jungers WL, Goodman SM, Wright HT, Jull AJ (2004). "A chronology for late prehistoric Madagascar". Journal of Human Evolution. 47 (1–2): 25–63. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.05.005. PMID 15288523.

- 1 2 Gray, RD; Drummond, AJ; Greenhill, SJ (2009). "Language Phylogenies Reveal Expansion Pulses and Pauses in Pacific Settlement". Science. 323 (5913): 479–483. Bibcode:2009Sci...323..479G. doi:10.1126/science.1166858. PMID 19164742.

- ↑ Kun, Ho Chuan (2006). "On the Origins of Taiwan Austronesians". In K. R. Howe. Vaka Moana: Voyages of the Ancestors (3rd ed.). Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-0-8248-3213-1.

- ↑ Bellwood, Peter (2014). The Global Prehistory of Human Migration. p. 213.

- ↑ Goodenough, Ward Hunt (1996). Prehistoric Settlement of the Pacific, Volume 86, Part 5. American Philosophical Society. pp. 127–128.

- ↑ Li, H; Huang, Y; Mustavich, LF; et al. (November 2007). "Y chromosomes of prehistoric people along the Yangtze River". Hum. Genet. 122 (3–4): 383–8. doi:10.1007/s00439-007-0407-2. PMID 17657509.

- ↑ Blench, Roger. 2014. Suppose we are wrong about the Austronesian settlement of Taiwan? m.s.

- ↑ Jiao, Tianlong. 2007. The Neolithic of Southeast China: Cultural Transformation and Regional Interaction on the Coast. Cambria Press.

- ↑ Jiao, Tianlong. 2013. "The Neolithic Archaeology of Southeast China." In Underhill, Anne P., et al. A Companion to Chinese Archaeology, 599-611. Wiley-Blackwell.

- ↑ Pawley, A. (2002). "The Austronesian dispersal: languages, technologies and people". In Bellwood, Peter S.; Renfrew, Colin. Examining the farming/language dispersal hypothesis. McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge. pp. 251–273. ISBN 1902937201.

- ↑ http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2016/10/game-changing-study-suggests-first-polynesians-voyaged-all-way-east-asia

- ↑ Van Tilburg, Jo Anne. 1994. Easter Island: Archaeology, Ecology and Culture. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press

- ↑ Langdon, Robert. The Bamboo Raft as a Key to the Introduction of the Sweet Potato in Prehistoric Polynesia, The Journal of Pacific History', Vol. 36, No. 1, 2001

- ↑ "Genetic 'map' of Asia's diversity". BBC News. 11 December 2009.

- ↑ Kumar, Vikrant (11 December 2009). "Scientific consortium maps the range of genetic diversity in Asia, and traces the genetic origins of Asian populations". HUGO Matters. Human Genome Organisation. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014.

- ↑ HUGO Pan-Asian SNP Consortium; Abdulla MA; Ahmed I; Assawamakin A; et al. (December 2009). "Mapping human genetic diversity in Asia". Science. 326 (5959): 1541–5. Bibcode:2009Sci...326.1541.. doi:10.1126/science.1177074. PMID 20007900.

- ↑ Philippine History by Maria Christine N. Halili. "Chapter 3: Precolonial Philippines" (Published by Rex Bookstore; Manila, Sampaloc St. Year 2004)

- ↑ Oktora, Samuel; Ama, Kornelis Kewa (3 April 2010). "Lima Abad Semana Santa Larantuka" (in Indonesian). Kompas. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ↑ The Sanskrit loanword "Ekasila" : "Eka" means 1, "Sila" means "pillar", "principle" appeared in Sukarno's speech

- ↑ In Kedukan Bukit inscription the numeral tlu ratus appears as three hundred, tlu as three, in http://www.wordsense.eu/telu/ the word telu is referred to as three in Malay, although the use of telu is very rare.

- ↑ The Sanskrit loanword "Trisila" : "Tri" means 3, "Sila" means "pillar", "principle" appeared in Sukarno's speech

- ↑ The Sanskrit loanword: Pancasila is the 5 principles of sukarno explained here: Pancasila (politics), "Panca" means 5, "Sila" means "pillar", "principle".

- ↑ Lapan is a known shortage of Delapan.

- ↑ In Kedukan Bukit inscription the numeral tlu ratus appears as three hundred, tlu as three, in http://www.wordsense.eu/telu/ the word telu is referred to as three in Malay, although the use of telu is very rare.

- ↑ Krutak, Lars (2005–2006). "Return of the Headhunters: The Philippine Tattoo Revival". The Vanishing Tattoo. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- ↑ Kirch, Patrick V. (1998). "Lapita and Its Aftermath: the Austronesian Settlement of Oceania". In Goodenough, Ward H. Prehistoric Settlement of the Pacific, Volume 86, Part 5. American Philosophical Society. p. 70. ISBN 0-87169-865-X.

- ↑ Bellwood, Peter (2007). Prehistory of the Indo-Malaysian Archipelago. ANU E Press. p. 151. ISBN 9781921313127.

- ↑ Best, Eldson (1904). "The Uhi-Maori, or Native Tattooing Instruments". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 13 (3): 166–172.

- ↑ Major-General Robley (1896). "Moko and Mokamokai — Chapter I — How Moko First Became Knows to Europeans". Moko; or Maori Tattooing. Chapman and Hall Limited. p. 5. Retrieved 2009-09-26.

- ↑ Cummins, Joseph (2006). History's Great Untold Stories: Obscure Events of Lasting Importance. Pier 9. p. 133. ISBN 9781740458085.

- ↑ Lach, Donald F. & Van Kley, Edwin J. (1998). Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume III: A Century of Advance. Book 3: Southeast Asia. University of Chicago Press. p. 1499. ISBN 9780226467689.

- ↑ Masferré, Eduardo (1999). A Tribute to the Philippine Cordillera. Asiatype, Inc. p. 64. ISBN 9789719171201.

- ↑ Salvador-Amores, Analyn Ikin V. (2002). "Batek: Traditional Tattoos and Identities in Contemporary Kalinga, North Luzon Philippines". Humanities Diliman. 3 (1): 105–142.

- ↑ Van Dinter; Maarten Hesselt (2005). The World Of Tattoo: An Illustrated History. Centraal Boekhuis. p. 64. ISBN 9789068321920.

- ↑ Krutak, Lars (2009). "The Kalinga Batok (Tattoo) Festival". The Vanishing Tattoo. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- ↑ The Austronesian Moment

- ↑ "臺灣原住民族的Y 染色體多樣性與華南史前文化的關連性" (PDF).

- ↑ Li, Hui; Huang, Ying; Mustavich, Laura F.; Zhang, Fan; Tan, Jing-Ze; Wang, ling-E; Qian, Ji; Gao, Meng-He & Jin, Li (2007). "Y chromosomes of prehistoric people along the Yangtze River" (PDF). Human Genetics. 122 (3–4): 383–388. doi:10.1007/s00439-007-0407-2. PMID 17657509. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 December 2013.

- ↑ Andreia Brandão, Ken Khong Eng, Teresa Rito, Bruno Cavadas, David Bulbeck, Francesca Gandini, Maria Pala, Maru Mormina, Bob Hudson, Joyce White, Tsang-Ming Ko, Mokhtar Saidin, Zainuddin Zafarina, Stephen Oppenheimer, Martin B. Richards, Luísa Pereira, and Pedro Soares (2016). "Quantifying the legacy of the Chinese Neolithic on the maternal genetic heritage of Taiwan and Island Southeast Asia". Hum. Genet. 135: 363–376. doi:10.1007/s00439-016-1640-3. PMC 4796337. PMID 26875094.

- ↑ Jean A Trejaut, Estella S Poloni, Ju-Chen Yen, Ying-Hui Lai, Jun-Hun Loo, Chien-Liang Lee, Chun-Lin He and Marie Lin (2014). "Taiwan Y-chromosomal DNA variation and its relationship with Island Southeast Asia". BMC Genetics. 15 (77). doi:10.1186/1471-2156-15-77. PMID 24965575.

- ↑ Lan-Hai Wei, Shi Yan, Yik-Ying Teo, Yun-Zhi Huang, Ling-Xiang Wang, Ge Yu, Woei-Yuh Saw, Rick Twee-Hee Ong, Yan Lu,4 Chao Zhang, Shu-Hua Xu, Li Jin, and Hui Li (April 2017). "Phylogeography of Y-chromosome haplogroup O3a2b2-N6 reveals patrilineal traces of Austronesian populations on the eastern coastal regions of Asia". PLoS One. 12 (4). Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1275080W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0175080. PMC 5381892. PMID 28380021.

- ↑ Albert Min-Shan Ko, Chung-Yu Chen, Qiaomei Fu, Frederick Delfin, Mingkun Li, Hung-Lin Chiu, Mark Stoneking, and Ying-Chin Ko (March 6, 2014). "Early Austronesians: Into and Out Of Taiwan". Am J Hum Genet. 94 (3): 426–436. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.02.003. PMC 3951936. PMID 24607387.

Books

- Bellwood, Peter S. (1979). Man's conquest of the Pacific: The prehistory of Southeast Asia and Oceania. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195201031.

- Bellwood, Peter (2007). Prehistory of the Indo-Malaysian Archipelago (3rd, revised ed.). ANU E Press. ISBN 978-1-921313-12-7.

- Bellwood, Peter; Fox, James J.; Tryon, Darrell, eds. (2006). The Austronesians : historical and comparative perspectives. Australian National University. ISBN 1920942858.

- Diamond, Jared M. (1998). Guns, Germs, and Steel. Vintage. ISBN 84-8306-667-X.

- Benitez-Johannot, Purissima, ed. (2009). Paths of Origins. ArtPostAsia Books. ISBN 9719429208. Archived from the original on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- James J. Fox (2006). Origins, Ancestry and Alliance: Explorations in Austronesian Ethnography. ANU E Press. ISBN 978-1-920942-87-8.

External links

- Cristian Capelli; et al. (2001). "A Predominantly Indigenous Paternal Heritage for the Austronesian-Speaking Peoples of Insular Southeast Asia and Oceania" (PDF). American Journal of Human Genetics. 68 (2): 432–443. doi:10.1086/318205. PMC 1235276. PMID 11170891. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2010.

- Books, some online, on Austronesian subjects by the Australian National University

- Encyclopædia Britannica: Austronesian Languages