Sundanese language

| Sundanese | |

|---|---|

|

ᮘᮞ ᮞᮥᮔ᮪ᮓ Basa Sunda | |

| |

| Native to | Indonesia |

| Region | West Java, Banten, Jakarta, parts of western Central Java, southern Lampung |

| Ethnicity | Sundanese, Bantenese, Cirebonese, Badui |

Native speakers | 40 million (2016)[1] |

| Dialects |

Baduy language Bantenese language Brebian Sundanese Cirebonese Sundanese Northern Sundanese Priangan Sundanese |

|

Cacarakan (certain areas) Latin script (present) Pranagari (historical) Pegon script (Religious use only) Sundanese script (present; optional) Vatteluttu (historical) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

Banten (regional) West Java (regional) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

su |

| ISO 639-2 |

sun |

| ISO 639-3 |

sun – Sunda |

| Glottolog |

sund1251[3] |

| Linguasphere |

31-MFN-a |

Sundanese /sʌndəˈniːz/[4] (Basa Sunda /basa sʊnda/, in Sundanese script ᮘᮞ ᮞᮥᮔ᮪ᮓ, literally "language of Sunda") is a Malayo-Polynesian language spoken by the Sundanese. It has approximately 39 million native speakers in the western third of Java; they represent about 15% of Indonesia's total population.

Dialects

Sundanese appears to be most closely related to Madurese and Malay, and more distantly related to Javanese. It has several dialects, conventionally described according to the locations of the people:

- Western dialect, spoken in the provinces of Banten and some parts of Lampung;

- Northern dialect, spoken in Bogor, and northwestern coastal areas of West Java;

- Southern or Priangan dialect, spoken in Sukabumi, Cianjur, Bandung, Garut and Tasikmalaya

- Mid-east dialect, spoken in Cirebon, Majalengka and Indramayu,

- Northeast dialect, spoken in Kuningan, and Brebes (Central Java),

- Southeast dialect, spoken in Ciamis, Pangandaran, Banjar and Cilacap (Central Java).

The Priangan dialect, which covers the largest area where Sundanese people lives (Parahyangan in Sundanese), is the most widely spoken type of Sundanese language, taught in elementary till senior-high schools (equivalent to twelfth-year school grade) in West Java and Banten Province.

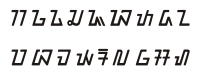

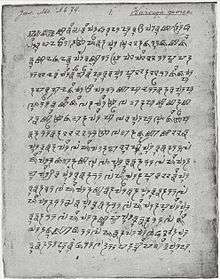

Writing

The language has been written in different writing systems throughout history. During the early Hindu-Buddhist era, the Vatteluttu and Nāgarī script were used. The Sundanese later then developed their own alphabet, the Old Sundanese script (Aksara Sunda Kuno). After the arrival of Islam, the Pegon script is also used, usually for religious purposes. The Latin script then began to be used after the arrival of Europeans. In modern times, most of Sundanese literature is written in Latin. The regional government of West Java and Banten are currently promoting the use of Standard Sundanese script (Aksara Sunda Baku) in public places and road signs. The Pegon script is still used mostly by pesantrens (Islamic boarding school) in West Java and Banten or in Sundanese Islamic literature.[5]

Phonology

Sundanese orthography is highly phonetic (see also Sundanese script). There are seven vowels[6]: a /a/, é /ɛ/, i /i/, o /ɔ/, u /u/, e /ə/, and eu /ɤ/. The consonantal phonemes are transcribed with the letters p, b, t, d, k, g, c (pronounced /tʃ/), j /d͡ʒ/, h, ng (/ŋ/), ny /ɲ/, m, n, s /s/, w, l, r /r~ɾ/, and y /j/. Other consonants that originally appear in Indonesian loanwords are mostly transferred into native consonants: f → p, v → p, sy → s, sh → s, z → j, and kh /x/ → h.

According to Müller-Gotama (2001) there are 18 consonants in the Sundanese phonology: /b/, /tʃ/, /d/, /g/, /h/, /dʒ/, /k/, /l/, /m/, /n/, /p/, /r/, /s/, /ŋ/, /t/, /ɲ/, /w/, /j/; however, influences from foreign languages have introduced several additional consonants such as /f/, /v/, /z/ (as in fonem, qur'an, xerox, zakat).

There are /w/ and /j/ as semi vowels, they function as glide sound between two different vowels, as in the words:

- kuéh - /kuwɛh/

- muih - /muwih/

- béar - /bejar/

- miang - /mijaŋ/

Phonemes /w/ and /j/ function as glide sounds between two different vowels as in the words:

- wa - rung

- wa - yang

- ba - wang

- ha - yang

- ku - ya

Register

Sundanese has an elaborate system of register distinguishing two basic levels of formality: kasar (low, informal) and lemes (high, formal).[7]

For many words, there are distinct kasar and lemes forms, e.g. arek (kasar) vs. bade (lemes) "want", maca (kasar) vs. maos (lemes) "read". In the lemes level, some words further distinguish humble and respectful forms, the former being used to refer to oneself, and the latter for the addressee and third persons, e.g. rorompok "(my own) house" vs. bumi "(your or someone else's) house" (the kasar form is imah).

Similar systems of speech levels are found in Javanese, Madurese, Balinese and Sasak.

Basic grammar

Root word

Root verb

| English | Sundanese (normal) | Sundanese (polite) |

|---|---|---|

| eat .. | dahar .. | tuang ..(for other) neda ..(for myself) |

| drink .. | inum .. | leueut .. |

| write .. | tulis .. | serat .. |

| read .. | maca .. | maos .. |

| forget .. | poho .. | hilap .. |

| remember .. | inget .. | emut .. |

| sit .. | diuk .. | calik .. linggih |

| standing .. | nangtung .. | adeg .. |

| walk .. | leumpang .. | papah .. |

Plural form

Other Austronesian languages commonly use reduplication to create plural forms. However, Sundanese inserts the ar infix into the stem word. If the stem word starts with l, or contains r following the infix, the infix ar becomes al. Also, as with other Sundanese infixes (such as um), if the word starts with vowel, the infix becomes a prefix. Examples:

- Mangga A, tarahuna haneut kénéh. "Please sir, the bean curds are still warm/hot." The plural form of tahu 'bean curd, tofu' is formed by infixing ar after the initial consonant.

- Barudak leutik lalumpatan. "Small children running around." Barudak "children" is formed from budak (child) with the ar infix; in lumpat (run) the ar infix becomes al because lumpat starts with l.

- Ieu kaén batik aralus sadayana. "All of these batik clothes are beautiful." Formed from alus (nice, beautiful, good) with the infix ar that becomes a prefix because alus starts with a vowel. It denotes the adjective "beautiful" for the plural subject/noun (batik clothes).

- Siswa sakola éta mah balageur. "The students of that school are well-behaved." Formed from bageur ("good-behaving, nice, polite, helpful") with the infix ar, which becomes al because of r in the root, to denote the adjective "well-behaved" for plural students.

However, it is reported that this use of al instead of ar (as illustrated in (4) above) does not to occur if the 'r' is in onset of a neighbouring syllable. For example, the plural form of the adjective curiga (suspicious) is caruriga and not *caluriga, because the 'r' in the root occurs at the start of the following syllable.[8]

The prefix can be reduplicated to denote very-, or the plural of groups. For example, "bararudak" denotes many, many children or many groups of children (budak is child in Sundanese). Another example, "balalageur" denotes plural adjective of "very well-behaved".

Active form

Most active forms of Sundanese verbs are identical to the root, as with diuk "sit" or dahar "eat". Some others depend on the initial phoneme in the root:

- Initial /d/, /b/, /f/, /g/, /h/, /j/, /l/, /r/, /w/, /z/ can be put after prefix nga like in ngadahar.

- Initial /i/, /e/, /u/, /a/, /o/ can be put after prefix ng like in nginum "drink".

Negation

Abdi henteu acan neda. "I have not eaten yet."

Buku abdi mah sanes nu ieu. "My book is not this one."

Question

Dupi -(question)

example:saya

Polite-

- Dupi Bapa aya di bumi? "Is your father at home?"

- Dupi bumi di palih mana? "Where do you live?"

Passive form

Buku dibantun ku abdi. "The book is brought by me." Dibantun is the passive form ngabantun "bring".

Pulpen ditambut ku abdi. "The pen is borrowed by me."

Soal ieu digawekeun ku abdi. "This problem is done by me."

Adjectives

Examples:

teuas (hard), tiis (cool), hipu (soft), lada (hot, usually for foods), haneut (warm), etc.

Prepositions

Place

| English | Sundanese (normal) | Sundanese (polite) |

|---|---|---|

| above .. | diluhureun .. | diluhureun .. |

| behind .. | ditukangeun .. | dipengkereun .. |

| under .. | dihandapeun .. | dihandapeun .. |

| inside .. | di jero .. | di lebet .. |

| outside .. | di luar .. | di luar .. |

| between .. and .. | di antara .. jeung .. | di antawis .. sareng .. |

| front .. | hareup .. | payun .. |

| back .. | tukang .. | pengker .. |

Time

| English | Sundanese (normal) | Sundanese (polite) |

|---|---|---|

| before | saacan | sateuacan |

| after | sanggeus | saparantos |

| during | basa | nalika |

| past | baheula | kapungkur |

Miscellaneous

| English | Sundanese (normal) | Sundanese (polite) |

|---|---|---|

| from | tina/ti | tina |

| for | jang | kanggo |

See also

References

- ↑ Muamar, Aam (2016-08-08). "Mempertahankan Eksistensi Bahasa Sunda" [Maintaining the existence of Sundanese Language]. Pikiran Rakyat (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2018-09-27.

- ↑ Anderbeck, Karl (2007). "An Initial Reconstruction of Proto-Lampungic: Phonology and Basic Vocabulary". Studies in Philippine Languages and Cultures. 16: 41–165.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Sundanese–Badui". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Bauer, Laurie (2007). The Linguistics Student's Handbook. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- ↑ Rosidi, Ajip (2010). Mengenang hidup orang lain: sejumlah obituari (in Indonesian). Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia. ISBN 9789799102225.

- ↑ Müller-Gotama, Franz (2001). Sundanese. Languages of the World. Materials. 369. Munich: LINCOM Europa.

- ↑ Anderson, E.A. (1997). "The use of speech levels in Sundanese". In Clark, M. (ed.). Papers in Southeast Asian Linguistics No. 16. Canberra: Australian National University.

- ↑ Bennett, Wm G. (2015). The Phonology of Consonants: Harmony, Dissimilation, and Correspondence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 132.

Further reading

Rigg, Jonathan (1862). A Dictionary of the Sunda Language of Java. Batavia: Lange & Co.

External links

| Sundanese edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Wikivoyage has a phrasebook for Sundanese. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sundanese language. |