Demographic history of Kosovo

This article includes information on the demographic history of Kosovo.

Prehistory

Archeological findings show that Bronze and Iron Age tombs were found only in Metohija, not in Kosovo proper.[1] The region was originally inhabited by Thracians, and subsequently by Illyrians, Celts[2][3] and Thracians.[3][4] During antiquity, the area was inhabitet by Dardani and by the fourth century the Dardanian Kingdom was found. The Dardani, whose exact ethno-linguistic affiliation is difficult to determine, were a prominent group in the region during the late Hellenistic and early Roman eras.[5] The area was originally populated with Thracians who were then exposed to Illyrian influence.[4][6] After Roman conquest of Illyria at 168 BC, Romans colonized and founded several cities in the region, like Ulpiana, Theranda, Vicianum,[7] incorporating it into the Roman province of Illyricum in 59 BC. Subsequently, it became part of Moesia Superior in AD 87. The region was exposed to an increasing number of 'barbarian' raids from the 4th century AD onwards, culminating with the Slavic migrations of the 6th and 7th centuries. Archaeologically, the early Middle Ages represent a hiatus in the material record,[8] and whatever was left of the native provincial population fused into the Slavs.[9]

Early and High Middle Ages

Slavs are mentioned in the area since the 520s AD, with the Slav tribe of Sklavenoi settling the Praetorian prefecture of Illyricum, the mythological founders of the Serbs were the White Serbs; "who settled in the Balkans during the rule of Emperor Heraclius" (610-641)[10] and they mixed with the natives. Archaeological findings suggest that there was steady population recovery and progression of the Slavic culture seen elsewhere throughout the Balkans. The region was absorbed into the Bulgarian Empire in the 850s, where Christianity and a Byzantine-Slavic culture was cemented in the region. It was re-taken by the Byzantines after 1018, and became part of the newly established Theme of Bulgaria. In 1054, the Great Schism divided the historical Roman Empire into a Western and Eastern part on religious basis; Kosovo, located in the Eastern part, became part of the Orthodox world. As the centre of Slavic resistance to Constantinople in the region, the region often switched between Serbian and Bulgarian rule on one hand and Byzantine on the other, until Serbian Grand Prince Stefan Nemanja secured it by the end of the 12th century.[11] An insight into the region is provided by the Byzantine historian-princess, Anna Comnena, who wrote of Serbs being the main inhabitants of the region (referring to it as "eastern Dalmatia" and the "former Moesia Superior").[12]

14th century

1321–31

The Dečani chrysobulls (1321–31) of Serbian king Stefan Dečanski contains a detailed list of households and villages in Metohija and northwestern Albania. The first charter concludes that this region was ethnically Serbian.[13] 89 settlements with 2,666 households were recorded, out of which 86 were Serbian (96,6%), and 3 were Albanian (3,3%); there were 2,166 livestock households of 2,666 agricultural households, out of which 2,122 were Serbian (98%), and 44 were Albanian (2%).[14]

In the 14th century in two chrysobulls or decrees by Serbian rulers, villages in the Kosovo area of Albanians alongside Vlachs are cited in the first as being between the White Drin and Lim rivers (1330), and in the second (1348) a total of nine Albanian villages are cited within the vicinity of Prizren.[15][16]

15th century

1455

The Ottoman cadastral tax census (defter) of 1455 in the Branković lands (covering most of present-day Kosovo) recorded:

- 480 villages,

- 13,693 adult males,

- 12,985 dwellings,

- 14,087 household heads (480 widows and 13,607 adult males).

Yugoslav and Serbian scholars have researched the defter, concluding that:[17]

- 13,000 Serb dwellings present in all 480 villages and towns

- 75 Vlach dwellings in 34 villages

- 46 Albanian dwellings in 23 villages

- 17 Bulgarian dwellings in 10 villages

- 5 Greek dwellings in Lauša, Vučitrn

- 1 Jewish dwelling in Vučitrn

- 1 Croat dwelling

Out of all names mentioned in this census, conducted by the Ottomans in 1455, covering areas of most of present-day Kosovo, 95.88% of all names were of Serbian origin, 1.90% of Roman origin, 1.56% of uncertain origin, 0.26% of Albanian origin, 0.25% of Greek origin, etc.[18][19]

1487

The defter of 1487 in the Branković lands recorded:

- Vučitrn district:

- Ipek (Peć) district:

- Ipek (town)

- 121 Christian households

- 33 Muslim households

- Suho Grlo and Metohija:

- 131 Christian households of which 52% in Suho Grlo were Serbs

- Donja Klina - 50% Serbs

- Dečani - 64% Serbs

- Rural areas:

- 6,124 Christian households (99%)

- 55 Muslim households (1%)

Scholarship on Kosovo has encompassed Ottoman provincial surveys that have revealed the 15th century ethnic composition of some Kosovo settlements, however both Serbian and Albanian historians using these records have made much of them while proving little.[20]

16th century

1520–1535

- Vučitrn: 19,614 households

- Christians

- 700 Muslim households (3,5%)

- Prizren

- Christians

- 359 Muslim households (2%)

1582–83

The 1582–83 defter of the Sanjak of Scutari recorded the Peć nahiya as having 235 villages of which some 30 have Albanian families besides the majorital Orthodox Serbs. The Altun-li nahiya had 41 villages with a Serb majority and Albanian minority.[21]

1591

Ottoman defter from 1591:[22]

17th–18th centuries

Significant clusters of Albanian populations lived in Kosovo especially in the west and centre before and after the Habsburg invasion of 1689–1690, while in Eastern Kosovo they were a small minority.[23][24] Due to the Ottoman-Habsburg wars and their aftermath, some Albanians from contemporary northern Albania and Western Kosovo settled within the wider Kosovo area in the second half of the 18th century, at times instigated by Ottoman authorities.[25][26]

The Great Turkish War of 1683–1699 between the Ottomans and the Habsburgs led to the flight of a substantial numbers of Serbs and Albanians who had sided with the Austrians, from within and outside Kosovo, to Austrian held Vojvodina and the Military Frontier – Patriarch Arsenije III, one of the refugees, referred to 30,000 or 40,000 souls, but a much later monastic source referred to 37,000 families. Serbian historians have used this second source to talk of a Great Migration of Serbs. Wars in 1717–1738 led to a second exodus of refugees (both Serbian and Albanian) from inside and outside Kosovo, together with reprisals and the enslavement and deportation of a number of Serbs and Albanians by the victorious Ottomans.[27]

19th century

19th century data about the population of Kosovo tend to be rather conflicting, giving sometimes numerical superiority to the Serbs and sometimes to the Albanians. The Ottoman statistics are regarded as unreliable, as the empire counted its citizens by religion rather than nationality, using birth records rather than surveys of individuals.

A study in 1838 by an Austrian physician, Dr. Joseph Müller, found Metohija to be mostly "Slavic" in character.[28] Müller gives data for the three counties (Bezirke) of Prizren, Peć and Đakovica which roughly covered Metohija, the portion adjacent to Albania and most affected by Albanian settlers. Out of 195,000 inhabitants in this region, Müller found:

- 114,000 Muslims (58%):

- Christians:

- 73,572 Eastern Orthodox Serbs (38%)

- 5,120 Roman Catholic Albanians (3%)

- 2,308 other non-Muslims (Janjevci etc.)

Müller's observations on towns:

- Peć: 11,050 Serbs, 500 Albanians

- Prizren: 16,800 Serbs, 6150 Albanians

- Đakovica: majority of Albanians, surrounding villages Serbian

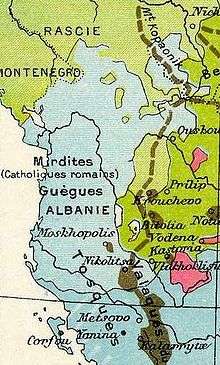

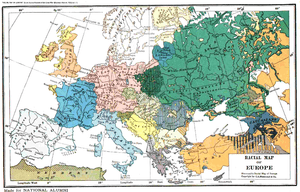

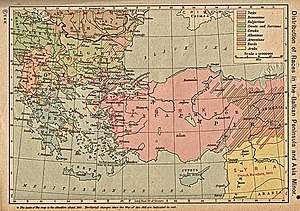

Map published by French ethnographer G. Lejean[29] in 1861 shows that Albanians lived on around 57% Kosovo while a similar map, published by British travellers G. M. Mackenzie and A. P. Irby[29] in 1867 shows slightly less; these maps don't show which population was larger overall. Nevethless, maps cannot be used to measure population as they leave out density.

A study done in 1871 by Austrian colonel Peter Kukulj[30] for the internal use of the Austro-Hungarian army showed that the mutesarifluk of Prizren (corresponding largely to present-day Kosovo) had some 500,000 inhabitants, of which:

- 318,000 Serbs (64%),

- 161,000 Albanians (32%),

- 10,000 Roma (Gypsies) and Circassians

- 2,000 Turks

Modern Serbian sources estimated that around 400,000[31] Serbs were cleansed out of the Vilayet of Kosovo between 1876 and 1912.

Maps published by German historian Kiepert[29] in 1876, J. Hahn[29] and Austrian consul K. Sax,[29] show that Albanians live on most of the territory of what is now Kosovo, however they don't show which population is larger. According to these, the regions of Kosovska Mitrovica and Kosovo Polje were settled mostly by Serbs, whereas most of the territory of western and eastern parts of today's province was settled by Muslim Albanians.

An Austrian statistics[32] published in 1899 estimated:

At the end of the 19th century, Spiridon Gopchevich, an Austrian traveller – comprised a statistics and published them in Vienna. They established that Prizren had 60,000 citizens of whom 11,000 were Christian Serbs and 36,000 Muslem Serbs. The remaining population were Turks, Albanians, Tzintzars and Roma. For Peć he said that it had 2,530 households of which 1,600 were Mohammedan, 700 Christian Serb, 200 Catholic Albanian and 10 Turkish.

During and after the Serbian–Ottoman War of 1876–78, between 30,000 and 70,000 Muslims, mostly Albanians, were expelled by the Serb army from the Sanjak of Niș (located north-east of contemporary Kosovo) and fled to the Kosovo Vilayet.[33][34][35][36][37][38] Serbs from the Lab region moved to Serbia during and after the war of 1876 and incoming Albanian refugees (muhaxhirë) repopulated their villages.[39] Apart from the Lab region, sizeable numbers of Albanian refugees were resettled in other parts of northern Kosovo alongside the new Ottoman-Serbian border.[40][41][42] Most Albanian refugees were resettled in over 30 large rural settlements in central and southeastern Kosovo.[39][41][43] Many refugees were also spread out and resettled in urban centers that increased their populations substantially.[44][41][45] Western diplomats reporting in 1878 placed the number of refugee families at 60,000 families in Macedonia, with 60-70,000 refugees from Serbia spread out within the vilayet of Kosovo.[46] The Ottoman governor of the Vilayet of Kosovo estimated in 1881 the refugees number to be around 65,000 with some resettled in the Sanjaks of Üsküp and Yeni Pazar.[46]

Note: Territory of Ottoman Kosovo Vilayet was quite different from modern-day Kosovo.

Early 20th century

British journalist H. Brailsford estimated in 1906[47] that two-thirds of the population of Kosovo was Albanian and one-third Serbian. The most populous western districts of Gjakova and Peć were said to have between 20,000 and 25,000 Albanian households, as against some 5,000 Serbian ones. A map of Alfred Stead,[48] published in 1909, shows that similar numbers of Serbs and Albanians were living in the territory.

German scholar Gustav Weigand gave the following statistical data about the population of Kosovo,[49] based on the pre-war situation in Kosovo in 1912:

- Pristina District: 67% Albanians, 30% Serbs

- Prizren District: 63% Albanians, 36% Serbs

- Vučitrn District: 90% Albanians, 10% Serbs

- Ferizaj District: 70% Albanians, 30% Serbs

- Gnjilane District: 75% Albanians, 23% Serbs

- Mitrovica District: 60% Serbs, 40% Albanians

Metohija with the town of Gjakova is furthermore defined as almost exclusively Albanian by Weigand.[49]

Citing Serbian sources, Noel Malcolm also states that in 1912 when Kosovo came under Serbian control, "the Orthodox Serb population [was] at less than 25%" of Kosovo's entire population.[50]

Interwar period

1921 census

- The 1921 Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes population census for the territories comprising modern day Kosovo listed 439,010 inhabitants:

- By religion:

- Muslims: 329,502 (75.1%)

- Eastern Orthodox Serbs: 93,203 (21.2%)

- Roman Catholics: 15,785 (3.6%)

- Jews: 427

- Greek Catholics: 26

- By native language:

- Albanian: 288,907 (65.8%)

- Serbian or Croatian: 114,095 (26.0%)

- Turkish: 27,915 (6.4%)

- Romanian-Cincarian: 402

- Slovene: 184

- German: 30

- Hungarian: 12

It should be noted that the Yugoslav government settled Serbs and Montenegrins in the region, after past depopulation due to wars and Muslim emigration to Turkey.

1931 census

- According to the 1931 Kingdom of Yugoslavia population census, there were 552,064 inhabitants in today's Kosovo.

- By religion:

- Muslims: 379,981 (68.83%)

- Orthodox Serbs: 150,745 (27.31%)

- Roman Catholics: 20,568 (3.73%)

- Evangelists: 114 (0.02%)

- other: 656 (0.12%)

Religious structure of Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1931 (territorial organization from 1961)

Religious structure of Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1931 (territorial organization from 1961)

- By native language:

- Albanians: 331,549 (60.06%)

- Serbs, Croats, Slovenes and Macedonians: 180,170 (32.64%)

- Hungarians: 426 (0.08%)

- Germans: 241 (0.04%)

- other Slavs: 771 (0.14%)

- other: 38,907 (7.05%)

Linguistic structure of Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1931 (territorial organization from 1961)

Linguistic structure of Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1931 (territorial organization from 1961)

World War II

Most of the territory of today's province was occupied by Italian-controlled Greater Albania, massacres of some 30,000[51][52] Serbs, ethnic cleansing of about 100[51] to 250,000[51][53] or more[52] occurred.

Nazi Germany estimated that from November 1943 to February 1944, 40 000 Serbs fled Italian-occupied Kosovo for Montenegro and Serbia.

Censuses

1948 census

727,820 total inhabitants:

- 498,242 Albanians (68.46%)

- 171,911 Serbs (23.62%)

- 28,050 Montenegrins (3.86%)

- 11,230 Roma (1.54%)

- 5,290 Croats (0.73%)

- 1,315 Turks (0.18%)

- 526 Macedonians (0.07%)

- 362 Russians (0.05%)

- 283 Slovenes (0.04%)

- 197 Germans (0.03%)

- 83 Hungarians (0.01%)

- 77 Bulgarians (0.01%)

- 39 Italians

- 31 Rusyns

- 29 Czechs

- 18 Romanians

- 2 Slovaks

- 9,679 undecided Muslims (1.33%)

- 456 other and unknown (0.06%)

1953 census

808,141 total inhabitants

- 524,559 Albanians (64.91%)

- 189,969 Serbs (23.51%)

- 34,583 Turks (4.28%)

- 31,343 Montenegrins (3.88%)

- 6,201 Croat (0.77%)

- 972 Macedonians (0.12%)

- 411 Slovenes (0.05%)

- 6,241 undecided Yugoslav (0.77%)

- 401 other Slav (0.05%)

- 13,561 others (1.68%)

1961 census

963,959 total inhabitants

- 646,604 Albanians (67.08%)

- 227,016 Serbs (23.55%)

- 37,588 Montenegrins (3.9%)

- 8,026 Ethnic Muslims (0.83%)

- 7,251 Croat (0.75%)

- 5,203 Yugoslavs (0.54%)

- 3,202 Romani (0.33%)

- 1,142 Macedonians (0.12%)

- 510 Slovenes (0.05%)

- 210 Hungarians (0.02%)

Ethnic structure of Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1961.

Ethnic structure of Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1961.- Ethnic structure of Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1961.

- Ethnic structure of Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1961.

Ethnic structure of Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1961.

Ethnic structure of Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1961.- Distribution of Albanians on Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1961.

- Distribution of Serbs on Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1961.

Distribution of Serbs on Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1961.

Distribution of Serbs on Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1961.- Distribution of Montenegrins on Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1961.

- Distribution of Croats on Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1961.

1971 census

1,243,693 total inhabitants

- 916,168 Albanians or 73.7%[53]

- 228,264 Serbs (18.4%)

- 31,555 Montenegrins (2.5%)

- 26,000 Slavic Muslims (2.1%)

- 14,593 Romani (1.2%)

- 12,244 Turks (1.0%)

- 8,000 Croats (0.7%)

- 920 Yugoslavs (0.1%)

- Ethnic structure of Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1971.

Ethnic structure of Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1971.

Ethnic structure of Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1971.- Ethnic structure of Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1971.

Distribution of Albanians on Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1971.

Distribution of Albanians on Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1971.- Distribution of Albanians on Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1971.

- Distribution of Serbs on Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1971.

- Distribution of Montenegrins on Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1971.

- Distribution of Muslims on Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1971.

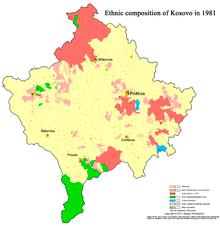

1981 census

1,584,558 total inhabitants

- 1,226,736 Albanians (77.42%)

- 209,498 Serbs (13.2%)

- 27,028 Montenegrins (1.7%)

- 2,676 Yugoslavs (0.2%)

Ethnic structure of Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1981.

Ethnic structure of Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1981.- Ethnic structure of Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1981.

Ethnic structure of Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1981.

Ethnic structure of Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1981.- Distribution of Albanians on Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1981.

Distribution of Albanians on Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1981.

Distribution of Albanians on Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1981.- Distribution of Serbs on Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1981.

Distribution of Muslims on Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1981.

Distribution of Muslims on Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1981.- Distribution of Montenegrins on Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1981.

Distribution of Roma on Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1981.

Distribution of Roma on Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1981. Ethnic composition of Kosovo in 1981 with Serb enclaves shown as in 2011

Ethnic composition of Kosovo in 1981 with Serb enclaves shown as in 2011

1991 census

Registered population

Official Yugoslav statistical results, almost all Albanians and some Roma, Muslims boycott the census following a call by Ibrahim Rugova to boycott Serbian institutions.

359,346 total population

- By ethnicity:

- 194,190 Serbs [54]

- 57,758 Muslims (minority boycotted)

- 44,307 Roma (minority boycotted)

- 20,356 Montenegrins

- 9,091 Albanians (majority boycotted)

- 10,446 Turks

- 8,062 Croats (Janjevci, Letnicani)

- 3,457 Yugoslavs

- Ethnic structure of Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1991 (registered population)

- Distribution of Roma in Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1991.

- By religion:

- 216,742 (60,32%) Orthodox

- 126,577 (35,22%) Muslims

- 9,990 (2,78%) Catholics

- 1,036 (0,29) Atheist

- 4,417 (1,23) Unknown

Religious structure of Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1991. (registered population)

Religious structure of Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1991. (registered population)

Estimated population

Statistical office of Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija estimated total number of Albanians, Muslims and Roma.

1,956,196 Total population

- 1,596,072 Albanians (81.6%)

- 194,190 Serbs (9.9%)

- 66,189 Muslims (3.4%)

- 45,745 Roma (2.34%)

- 20,365 Montenegrins (1.04%)

- 10,445 Turks (0.53%)

- 8,062 Croats (Janjevci, Letnicani) (0.41)

- 3,457 Yugoslavs (0.18%)

- 11,656 others (0.6%)

- Ethnic structure of Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1991

Ethnic structure of Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1991

Ethnic structure of Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1991 Share of Albanians on Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1991

Share of Albanians on Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1991 Share of Serbs on Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1991

Share of Serbs on Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1991 Share of Muslims on Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1991

Share of Muslims on Kosovo and Metohija by settlements 1991.png) Ethnic map of Kosovo, 1991 data

Ethnic map of Kosovo, 1991 data

The corrections should not be taken to be fully accurate. The number of Albanians is sometimes regarded as being an underestimate. On the other hand, it is sometimes regarded as an overestimate, being derived from earlier censa which are believed to be overestimates. The Statistical Office of Kosovo states that the quality of the 1991 census is "questionable." .

In September 1993, the Bosniak parliament returned their historical name Bosniaks. Some Kosovar Muslims have started using this term to refer to themselves since.

2011 census

In the 2011 census there were 1,739,825 inhabitants. ECMI "calls for caution when referring to the 2011 census", due to the boycott by Serb-majority municipalities in North Kosovo and the partial boycott by Serb and Roma in southern Kosovo.[55] According to the data, this is the ethnic composition of Kosovo:

- Albanians: 1,616,869 (92.9%)

- Serbs*: 25,532 (1.5%)

- Bosniaks: 27,553 (1.6%)

- Turks: 18,738 (1.1%)

- Ashkali: 15,436 (0.9%)

- Egyptians: 11,524 (0.6%)

- Gorani: 10,265 (0.6%)

- Romani: 8,824 (0.5%)

- Other: 2352 (0.1%)

- Unspecified: 2752 (0.1%)

The Ashkali and Balkan Egyptians are, in fact, Roma, but who self identify in such terms to distinguish itself from the Romani people.

- Kosovo ethnic map 2011 by settlement.

- Distribution of Albanians in Kosovo 2011 by settlements.

- Distribution of Serbs in Kosovo by settlements 2011.

- Distribution of Bosniaks in Kosovo by settlements.

- Distribution of Turks in Kosovo by settlements.

- Distribution of Gorani's in Kosovo by settlements.

- Distribution of Roma, Ashkali and Egyptians in Kosovo by settlements.

See also

References

- ↑ Djordje Janković: Middle Ages in Noel Malcolm's "Kosovo. A Short History" and Real Facts Archived 17 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ The central Balkan tribes in pre-Roman times: Triballi, Autariatae, Dardani, Scordisci and Moesians by Fanula Papazoglu, ISBN 90-256-0793-4, page 265

- 1 2 Pannonia and Upper Moesia: a history of the middle Danube provinces of the Roman EmpireThe Provinces of the Roman Empire, Vol. 4, ISBN 0710077149, 9780710077141, 1974, page 9

- 1 2 Wilkes, J. J. The Illyrians, 1992, ISBN 0-631-19807-5, page 85, "Whether the Dardanians were an Illyrian or a Thracian people has been much debated and one view suggests that the area was originally populated with Thracians who then exposed to direct contact with illyrians over a long period."

- ↑ N G Hammond, The Kingdoms of Illyria c. 400 – 167 BC. Collected Studies, Vol 2, 1993

- ↑ "the Dardanians [...] living in the frontiers of the Illyrian and the Thracian worlds retained their individuality and, alone among the peoples of that region succeeded in maintaining themselves as an ethnic unity even when they were militarily and politically subjected by the Roman arms [...] and when at the end of the ancient world, the Balkans were involved in far-reaching ethnic perturbations, the Dardanians, of all the Central Balkan tribes, played the greatest part in the genesis of the new peoples who took the place of the old" — The central Balkan tribes in pre-Roman times: Triballi, Autariatae, Dardanians, Scordisci and Moesians, Amsterdam 1978, by Fanula Papazoglu, ISBN 90-256-0793-4, p. 131.

- ↑ Hauptstädte in Südosteuropa: Geschichte, Funktion, nationale Symbolkraft by Harald Heppner, page 134

- ↑ Curta 2001, p. 189.

- ↑ Aleksandar Stipčević (1977). The Illyrians: history and culture. Noyes Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-8155-5052-5.

- ↑ Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De administrando imperio

- ↑ Fine 1994, p. 7

the Hungarian attack launched in 1183 with which Nemanja was allied [...] was able to conquer Kosovo and Metohija, including Prizren.

- ↑ Anne Comnène, Alexiade – Règne de l'Empereur Alexis I Comnène 1081–1118, texte etabli et traduit par B. Leib, Paris 1937–1945, II, 147–148, 157, 166, 184

- ↑ Milica Grković (2004). "Dečanski hrisovulja ili raskošni svitak" [Dečani chrysobull...] (PDF). Zbornik Matice srpske za književnost i jezik. 52 (3): 623–626. Archived 26 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Pavle Ivić and Milica Grković (1976), Dečanske hrisovulje, Institute of Linguistics (Novi Sad)

- ↑ Malcolm, Noel (1998). Kosovo: A short history. Macmillan. p. 54. ISBN 9780810874831. "From the details of the monastic estates given in the chrysobulls, further information can be gleaned about these Vlachs and Albanians. The earliest reference is in one of Nemanja’s charters giving property to Hilandar, the Serbian monastery on Mount Athos: 170 Vlachs are mentioned, probably located in villages round Prizren. When Dečanski founded his monastery of Decani in 1330, he referred to ‘villages and katuns of Vlachs and Albanians’ in the area of the white Drin: a katun (alb.:katund) was a shepherding settlement. And Dusan’s chrysobull of 1348 for the Monastery of the Holy Archangels in Prizren mentions a total of nine Albanian katuns."

- ↑ Wilkinson, Henry Robert (1955). "Jugoslav Kosmet: The evolution of a frontier province and its landscape". Transactions and Papers (Institute of British Geographers). 21: 183. JSTOR 621279. "The monastery at Dečani stands on a terrace commanding passes into High Albania. When Stefan Uros III founded it in 1330, he gave it many villages in the plain and catuns of Vlachs and Albanians between the Lim and the Beli Drim. Vlachs and Albanians had to carry salt for the monastery and provide it with serf labour."

- ↑ In 1972 the Sarajevo Institute of Middle Eastern Studies translated the original Turkish census and published an analysis of it Kovačević Mr. Ešref, Handžić A., Hadžibegović H. Oblast Brankovića - Opširni katastarski popis iz 1455., Orijentalni institut, Sarajevo 1972. Subsequently others have covered the subject as well such as Vukanović Tatomir, Srbi na Kosovu, Vranje, 1986.

- ↑ https://www.scribd.com/doc/98035320/Oblast-Brankovica-Opsirni-Katastarski-Popis-Iz-1455-Godine. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ (PDF) http://www.eparhija-prizren.com/sites/default/files/users/4/brankovici_popis_pregled.pdf. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Anscombe, Frederick (2006). "The Ottoman Empire in Recent International Politics - II: The Case of Kosovo". The International History Review. 28 (4): 785. JSTOR 40109813. "While the ethnic roots of some settlements can be determined from the Ottoman records, Serbian and Albanian historians have at times read too much into them in their running dispute over the ethnic history of early Ottoman Kosovo. Their attempts to use early Ottoman provincial surveys (tahrir defterleri) to gauge the ethnic make-up of the population in the fifteenth century have proved little."

- ↑ Varia turcica IV. Comité international d'etudes pré-Ottomanes et Ottomanes. VIth Symposium Cambridge, 1-4t July 1984, Istanbul-Paris-Leiden 1987, pp. 105-114

- ↑ TKGM, TD № 55 (412), (Defter sandžaka Prizren iz 1591. godine).

- ↑ Anscombe, Frederick F, (2006). "The Ottoman Empire in Recent International Politics – II: The Case of Kosovo". The International History Review. 28.(4): 767–774, 785–788. "While the ethnic roots of some settlements can be determined from the Ottoman records, Serbian and Albanian historians have at times read too much into them in their running dispute over the ethnic history of early Ottoman Kosovo. Their attempts to use early Ottoman provincial surveys (tahrir defterleri) to gauge the ethnic make—up of the population in the fifteenth century have proved little. Leaving aside questions arising from the dialects and pronunciation of the census scribes, interpreters, and even priests who baptized those recorded, no natural law binds ethnicity to name. Imitation, in which the customs, tastes, and even names of those in the public eye are copied by the less exalted, is a time—tested tradition and one followed in the Ottoman Empire. Some Christian sipahis in early Ottoman Albania took such Turkic names as Timurtaş, for example, in a kind of cultural conformity completed later by conversion to Islam. Such cultural mimicry makes onomastics an inappropriate tool for anyone wishing to use Ottoman records to prove claims so modern as to have been irrelevant to the pre—modern state. The seventeenth—century Ottoman notable arid author Evliya Çelebi, who wrote a massive account of his travels around the empire and abroad, included in it details of local society that normally would not appear in official correspondence; for this reason his account of a visit to several towns in Kosovo in 1660 is extremely valuable. Evliya confirms that western and at least parts of central Kosovo were ‘Arnavud’. He notes that the town of Vučitrn had few speakers of ‘Boşnakca’; its inhabitants spoke Albanian or Turkish. He terms the highlands around Tetovo (in Macedonia), Peć, and Prizren the ‘mountains of Arnavudluk’. Elsewhere, he states that ‘the mountains of Peć’ lay in Arnavudluk, from which issued one of the rivers converging at Mitrovica, just north-west of which he sites Kosovo’s border with Bosna. This river, the Ibar, flows from a source in the mountains of Montenegro north—north—west of Peć, in the region of Rozaje to which the Këlmendi would later be moved. He names the other river running by Mitrovica as the Kılab and says that it, too, had its source in Aravudluk; by this he apparently meant the Lab, which today is the name of the river descending from mountains north—east of Mitrovica to join the Sitnica north of Priština. As Evliya travelled south, he appears to have named the entire stretch of river he was following the Kılab, not noting the change of name when he took the right fork at the confluence of the Lab and Sitnica. Thus, Evliya states that the tomb of Murad I, killed in the battle of Kosovo Polje, stood beside the Kılab, although it stands near the Sitnica outside Priština. Despite the confusion of names, Evliya included in Arnavudluk not only the western fringe of Kosovo, but also the central mountains from which the Sitnica (‘Kılab’) and its first tributaries descend. Given that a large Albanian population lived in Kosovo, especially in the west and centre, both before and after the Habsburg invasion of 1689–90, it remains possible, in theory, that at that time in the Ottoman Empire, one people emigrated en masse and another immigrated to take its place.

- ↑ Malcolm, Noel (1998). Kosovo: A short history. Macmillan. p. 114. "What a straightforward reading of all this evidence would suggest is that there were significant reservoirs of a mainly Catholic Albanian-speaking population in parts of Western Kosovo, and evidence from the following century suggests that many of these eventually became Muslims. Whether Albanian-speakers were a majority in Western Kosovo at this time seems very doubtful, and it is clear that they were only a small minority in the east. On the other hand, it is also clear that the Albanian minority in Eastern Kosovo predated the Ottoman conquest."

- ↑ Jagodić 1998, para. 10, 12.

- ↑ Geniş, Şerife, and Kelly Lynne Maynard (2009). "Formation of a diasporic community: The history of migration and resettlement of Muslim Albanians in the Black Sea Region of Turkey." Middle Eastern Studies. 45. (4): 556–557: Using secondary sources, we establish that there have been Albanians living in the area of Nish for at least 500 years, that the Ottoman Empire controlled the area from the fourteenth to nineteenth centuries which led to many Albanians converting to Islam, that the Muslim Albanians of Nish were forced to leave in 1878, and that at that time most of these Nishan Albanians migrated south into Kosovo, although some went to Skopje in Macedonia. ; pp. 557–558. In 1690 much of the population of the city and surrounding area was killed or fled, and there was an emigration of Albanians from the Malësia e Madhe (North Central Albania/Eastern Montenegro) and Dukagjin Plateau (Western Kosovo) into Nish.

- ↑ Noel Malcolm, Kosovo, A Short History pp.139–171

- ↑ Dr. Joseph Müller, Albanien, Rumelien und die Österreichisch-montenegrinische Gränze, Prag, 1844

- 1 2 3 4 5 H.R. Wilkinson, Maps and Politics; a review of the ethnographic cartography of Macedonia, Liverpool University Press, 1951

- ↑ Das Fürstenthum Serbien und Türkisch-Serbien, eine militärisch-geographische Skizze von Peter Kukolj, Major im k.k.Generalstabe, Wien 1871

- ↑ ISBN 86-17-09287-4: Kosta Nikolić, Nikola Žutić, Momčilo Pavlović, Zorica Špadijer: Историја за трећи разред гимназије, Belgrade, 2002, pg. 63

- ↑ Detailbeschreibung des Sandzaks Plevlje und des Vilajets Kosovo (Mit 8 Beilagen und 10 Taffeln), Als Manuskript gedruckt, Vien 1899, 80–81.

- ↑ Pllana, Emin (1985). "Les raisons de la manière de l'exode des refugies albanais du territoire du sandjak de Nish a Kosove (1878–1878) [The reasons for the manner of the exodus of Albanian refugees from the territory of the Sanjak of Niš to Kosovo (1878–1878)] ". Studia Albanica. 1: 189–190.

- ↑ Rizaj, Skënder (1981). "Nënte Dokumente angleze mbi Lidhjen Shqiptare të Prizrenit (1878–1880) [Nine English documents about the League of Prizren (1878–1880)]". Gjurmine Albanologjike (Seria e Shkencave Historike). 10: 198.

- ↑ Şimşir, Bilal N, (1968). Rumeli’den Türk göçleri. Emigrations turques des Balkans [Turkish emigrations from the Balkans]. Vol I. Belgeler-Documents. p. 737.

- ↑ Bataković, Dušan (1992). The Kosovo Chronicles. Plato.

- ↑ Elsie, Robert (2010). Historical Dictionary of Kosovo. Scarecrow Press. p. XXXII. ISBN 9780333666128.

- ↑ Stefanović, Djordje (2005). "Seeing the Albanians through Serbian eyes: The Inventors of the Tradition of Intolerance and their Critics, 1804–1939." European History Quarterly. 35. (3): 470.

- 1 2 Jagodić 1998, para. 29.

- ↑ Jagodić 1998, para. 31.

- 1 2 3 Uka, Sabit (2004a). Dëbimi i Shqiptarëve nga Sanxhaku i Nishit dhe vendosja e tyre në Kosovë:(1877/1878-1912)[The expulsion of the Albanians from Sanjak of Nish and their resettlement in Kosovo: (1877/1878-1912). Prishtina: Verana. pp. 194–286. ISBN 9789951864503.

- ↑ Osmani 2000, pp. 48–50.

- ↑ Osmani 2000, pp. 44–47, 50–51, 54–60.

- ↑ Jagodić, Miloš (1998). "The Emigration of Muslims from the New Serbian Regions 1877/1878". Balkanologie. 2 (2). para. 30.

- ↑ Osmani, Jusuf (2000). Kolonizimi Serb i Kosovës [Serbian colonization of Kosovo]. Era. pp. 43–64. ISBN 9789951040525.

- 1 2 Malcolm, Noel (1998). Kosovo: A short history. London: Macmillan. pp. 228–229. ISBN 9780333666128. "Precise figures are lacking, but one modern study concludes that the whole region contained more than 110,000 Albanians. By the end of 1878 Western officials were reporting that there were 60,000 families of Muslim refugees in Macedonia, ‘in a state of extreme destitution’, and 60-70,000 Albanian refugees from Serbia ‘scattered’ over the vilayet of Kosovo.... All these new arrivals were known as muhaxhirs (Trk.: muhacir Srb.: muhadžir), a general word for Muslim refugees. The total number of those who settled in Kosovo is not known with certainty: estimates ranged from 20,000 to 50,000 for Eastern Kosovo, while the governor of the vilayet gave a total of 65,000 in 1881, some of whom were in the sancaks of Skopje and Novi Pazar. At a rough estimate, 50,000 would seem a reasonable figure for those muhaxhirs of 1877-8 who settled in the territory of Kosovo itself. Apart from the Albanians, smaller numbers of Muslim Slavs came from Montenegro and Bosnia."

- ↑ H. N. Brailsford, Macedonia, Its Races and Their Future, London, 1906

- ↑ Servia by the Servians, Compiled and Edited by Alfred Stead, With a Map, London (William Heinemann), 1909. (Etnographical Map of Servia, Scale 1:2.750.000).

- 1 2 Gustav Weigand, Ethnographie von Makedonien, Leipzig, 1924; Густав Вайганд, Етнография на Македония (Bulgarian translation)

- ↑ "Is Kosovo Serbia? We ask a historian". The Guardian. 26 February 2008. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- 1 2 3 Serge Krizman, Maps of Yugoslavia at War, Washington 1943.

- 1 2 ISBN 86-17-09287-4: Kosta Nikolić, Nikola Žutić, Momčilo Pavlović, Zorica Špadijer: Историја за трећи разред гимназије природно-математичког смера и четврти разред гимназије општег и друштвено-језичког смера, Belgrade, 2002, pg. 182

- 1 2 Annexe I Archived 1 March 2003 at the Wayback Machine., by the Serbian Information Centre-London to a report of the Select Committee on Foreign Affairs of the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

- ↑ Bugajski, Janusz (2002). Political Parties of Eastern Europe: A Guide to Politics in the Post-Communist Era. New York: The Center for Strategic and International Studies. p. 479. ISBN 1563246767.

- ↑ "ECMI: Minority figures in Kosovo census to be used with reservations". ECMI.

Sources

- Curta, Florin (2001). The Making of the Slavs: History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, c. 500–700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.