South Slavic languages

| South Slavic | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Southeast Europe |

| Linguistic classification |

Indo-European

|

| Subdivisions |

|

| ISO 639-5 | zls |

| Glottolog | sout3147[1] |

Countries where a South Slavic language is the national language | |

| South Slavic languages and dialects | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Western South Slavic

|

||||||

|

Transitional dialects

|

||||||

|

Alphabets |

||||||

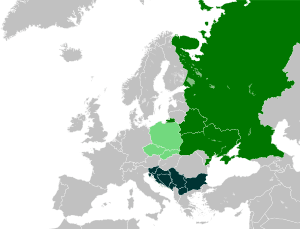

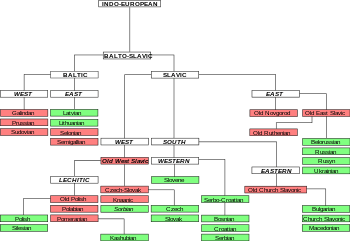

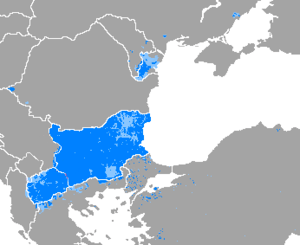

The South Slavic languages are one of three branches of the Slavic languages. There are approximately 30 million speakers, mainly in the Balkans. These are separated geographically from speakers of the other two Slavic branches (West and East) by a belt of German, Hungarian and Romanian speakers. The first South Slavic language to be written (the first attested Slavic language) was the variety spoken in Thessaloniki, now called Old Church Slavonic, in the ninth century. It is retained as a liturgical language in some South Slavic Orthodox churches in the form of various local Church Slavonic traditions.

Classification

The South Slavic languages constitute a dialect continuum.[2][3] Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian, and Montenegrin constitute a single dialect within this continuum.[4]

- Eastern

- Macedonian – (ISO 639-1 code: mk; ISO 639-2(B) code: mac; ISO 639-2(T) code: mkd; SIL code: mkd; Linguasphere: 53-AAA-ha)

- Bulgarian – (ISO 639-1 code: bg; ISO 639-2 code: bul; SIL code: bul; Linguasphere: 53-AAA-hb)

- Old Church Slavonic (extinct) – (ISO 639-1 code: cu; ISO 639-2 code: chu; SIL code: chu; Linguasphere: 53-AAA-a)

- Western

- Slovene (ISO 639-1 code: sl; ISO 639-2 code: slv; SIL code: slv; Linguasphere: 53-AAA-f)

- Serbo-Croatian (ISO 639-1 code: sh; ISO 639-2/3 code: hsb; SIL code: scr; Linguasphere: 53-AAA-g).

There are four national standard languages based on the Eastern Herzegovinian subdialect of the Shtokavian dialect of Serbo-Croatian:- Serbian (ISO 639-1 code: sr; ISO 639-2/3 code: srp; SIL code: srp)

- Croatian (ISO 639-1 code: hr; ISO 639-2/3 code: hrv; SIL code: hrv)

- Bosnian (ISO 639-1 code: bs; ISO 639-2/3 code: bos; SIL code: bos)

- Montenegrin (not completely standardized, but official in Montenegro, with published standard orthography)

Linguistic prehistory

The Slavic languages are part of the Balto-Slavic group, which belongs to the Indo-European language family. The South Slavic languages have been considered a genetic node in Slavic studies: defined by a set of phonological, morphological and lexical innovations (isoglosses) which separate it from the Western and Eastern Slavic groups. That view, however, has been challenged in recent decades (see below).

Some innovations encompassing all South Slavic languages are shared with the Eastern Slavic group, but not the Western Slavic. These include:[5]

- Consistent application of Slavic second palatalization before Proto-Slavic *v

- Loss of *d and *t before Proto-Slavic *l

- Merger of Proto-Slavic *ś (resulting from the second and third palatalization) with *s

This is illustrated in the following table:

| Late Proto-Slavic | South Slavic | West Slavic | East Slavic | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| reconstruction | meaning | Old Church Slavonic | Slovene | Serbo-Croatian | Bulgarian | Macedonian | Czech | Slovak | Polish | Belarusian | Russian | Ukrainian |

| *gvězda | star | звѣзда | zvezda | zv(ij)ezda/зв(иј)езда | звезда | ѕвезда | hvězda | hviezda | gwiazda | звязда | звезда | звізда |

| *květъ | flower, bloom | цвѣтъ | cvet | cv(ij)et/цв(иј)ет | цвете | цвет | květ | kvet | kwiat | кветка | цвет | цвіт, |

| *ordlo | plough | рало | ralo | ralo/рало | рало | рало | rádlo | radlo | radło | рала | орало, рало | рало |

| *vьśь | all | вьсь | ves | sav/сав | сиот | vše | všetok | wszyscy | весь | весь | весь | |

Several isoglosses have been identified which are thought to represent exclusive common innovations in the South Slavic language group. They are prevalently phonological in character, whereas morphological and syntactical isoglosses are much fewer in number. Sussex & Cubberly (2006:43–44) list the following phonological isoglosses:

- Merger of yers into schwa-like sound, which became /a/ in Serbo-Croatian, or split according to the retained hard/soft quality of the preceding consonant into /o e/ (Macedonian), or /ə e/ (Bulgarian)

- Proto-Slavic *ę > /e/

- Proto-Slavic *y > /i/, merging with the reflex of Proto-Slavic *i

- Proto-Slavic syllabic liquids *r̥ and *l̥ were retained, but *l̥ was subsequently lost in all the daughter languages with different outputs (> /u/ in Serbo-Croatian, > vowel+/l/ or /l/+vowel in Slovenian, Bulgarian and Macedonian), and *r̥ became [ər/rə] in Bulgarian. This development was identical to the loss of yer after a liquid consonant.

- Hardening of palatals and dental affricates; e.g. š' > š, č' > č, c' > c.

- South Slavic form of liquid metathesis (CoRC > CRaC, CoLC > CLaC etc.)

Most of these are not exclusive in character, however, and are shared with some languages of the Eastern and Western Slavic language groups (in particular, Central Slovakian dialects). On that basis, Matasović (2008) argues that South Slavic exists strictly as a geographical grouping, not forming a true genetic clade; in other words, there was never a proto-South Slavic language or a period in which all South Slavic dialects exhibited an exclusive set of extensive phonological, morphological or lexical changes (isoglosses) peculiar to them. Furthermore, Matasović argues, there was never a period of cultural or political unity in which Proto-South-Slavic could have existed during which Common South Slavic innovations could have occurred. Several South-Slavic-only lexical and morphological patterns which have been proposed have been postulated to represent common Slavic archaisms, or are shared with some Slovakian or Ukrainian dialects.

The South Slavic dialects form a dialectal continuum stretching from today's southern Austria to southeast Bulgaria.[6] On the level of dialectology, they are divided into Western South Slavic (Slovene and Serbo-Croatian dialects) and Eastern South Slavic (Bulgarian and Macedonian dialects); these represent separate migrations into the Balkans and were once separated by intervening Hungarian, Romanian, and Albanian populations; as these populations were assimilated, Eastern and Western South Slavic fused with Torlakian as a transitional dialect. On the other hand, the breakup of the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian Empires, followed by formation of nation-states in the 19th and 20th centuries, led to the development and codification of standard languages. Standard Slovene, Bulgarian, and Macedonian are based on distinct dialects.[7] The Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin, and Serbian standard variants[8] of the pluricentric Serbo-Croatian[9] are based on the same dialect (Shtokavian).[10] Thus, in most cases national and ethnic borders do not coincide with dialectal boundaries.

Note: Due to the differing political status of languages/dialects and different historical contexts, the classifications are arbitrary to some degree.

Dialectal classification

- South Slavic languages

- Eastern

- Bulgarian dialects

- Eastern Bulgarian dialects

- Western Bulgarian dialects

- Macedonian dialects

- Northern

- Western/Northwestern

- Eastern

- Southeastern

- Southwestern

- Bulgarian dialects

- Transitional (called Torlakian), including Transitional Bulgarian dialects in western Bulgaria, Prizren-Timok dialect in southeast Serbia and south Kosovo, northern Macedonian dialects

- Western

- Shtokavian dialect (Serbo-Croatian)

- Šumadija–Vojvodina (Ekavian, Neo-Shtokavian): Serbia

- Smederevo–Vršac (Ekavian, Old-Shtokavian): east-central Serbia

- Kosovo–Resava (Ekavian, Old-Shtokavian): north Kosovo, eastern central Serbia

- Zeta–Raška (Ijekavian, Old-Shtokavian), in south and east Montenegro and southwest Serbia

- Eastern Herzegovinian (Ijekavian, Neo-Shtokavian), Croatia, Bosnia, Serbia, Montenegro

- East-Bosnian (Ijekavian, Old-Shtokavian), in central and northern Bosnia

- Slavonian (mixed yat, Old-Shtokavian), in eastern Croatia

- Younger Ikavian (Ikavian), in Dalmatia, central Bosnia, northern Serbia

- Prizren–Timok (Ekavian, Old-Shtokavian), in southeast Serbia and south Kosovo

- Chakavian dialect

- Buzet subdialect: Croatia

- Western Chakavian subdialect: Croatia

- Southwestern Istrian subdialect: Croatia

- Northern Chakavian subdialect: Croatia

- Southern Chakavian subdialect: Croatia

- Lastovo subdialect: Croatia

- Kajkavian dialect, in Croatia

- Zagorje–Međimurje subdialect

- Križevci–Podravina subdialect

- Turopolje–Posavina subdialect

- Prigorski subdialect

- Donja Sutla subdialect

- Goranski subdialect

- Slovene

- Littoral Slovene: Primorsko; west Slovenia and Adriatic

- Rovte Slovene: Rovtarsko; between Littoral and Carniolan

- Upper and Lower Carniolan: Gorenjsko and Dolenjsko; central; basis of Standard Slovene

- Styrian: Štajersko; eastern Slovenia

- Pannonian or Prekmurje dialect: Panonsko; far eastern Slovenia

- Carinthian: Koroško; far north and northwest Slovenia

- Resian: Rozajansko; Italy, west of Carinthian

- Other

- Burgenland Croatian (mixed), minority in Austria and Hungary

- Shtokavian dialect (Serbo-Croatian)

- Eastern

Eastern group

The dialects that form the eastern group of South Slavic, spoken mostly in Bulgaria and Macedonia and adjacent areas in neighbouring countries, share a number of characteristics that set them apart from other Slavic languages:[12][13]

- the existence of a definite article (e.g. книга, book – книгата, the book, време, time – времето, the time)

- a near complete lack of noun cases

- the lack of a verb infinitive

- the formation of comparative forms of adjectives formed with the prefix по- (e.g. добър, по-добър (Bulg.)/добар, подобар (Maced.) – good, better)

- a future tense formed by the present form of the verb preceded by ще/ќе

- the existence of a renarrative mood (e.g. Той ме видял. (Bulg.)/Тој ме видел. (Maced.) – He supposedly saw me. Compare with Той ме видя./Тој ме виде. – He saw me.)

Bulgarian and Macedonian share some of their unusual characteristics with other languages in the Balkans, notably Greek and Albanian (see Balkan sprachbund).[12]

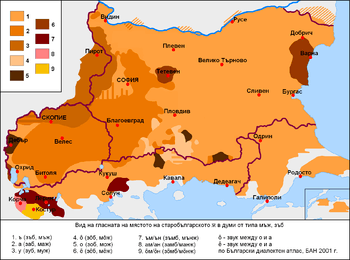

Bulgarian dialects

- Eastern Bulgarian dialects

- Western Bulgarian dialects (includes Torlakian dialect)

Macedonian dialects

- Southeast and East Macedonian dialects

- North Macedonian (including three Torlakian dialects)

- West Macedonian

Torlakian dialect in Serbian spoken language

- Southeastern Serbian Torlakian dialects are only spoken and unstandardized, as Serbian literary language only recognizes Shtokavian form (as other Serbo-Croatian languages)

Transitional South Slavic languages

Torlakian dialect

Another dialect, Torlakian, is spoken in southern and eastern Serbia, northern Macedonia and western Bulgaria; it is considered transitional between the Central and Eastern groups of South Slavic languages. Torlakian is thought to fit together with Bulgarian and Macedonian into the Balkan sprachbund, an area of linguistic convergence caused by long-term contact rather than genetic relation. Because of that some researchers tend to classify it as Eastern South Slavic.[14]

Western group

History

Each of these primary and secondary dialectal units breaks down into subdialects and accentological isoglosses by region. In the past (and currently, in isolated areas), it was not uncommon for individual villages to have their own words and phrases. However, during the 20th century the local dialects have been influenced by Štokavian standards through mass media and public education and much "local speech" has been lost (primarily in areas with larger populations). With the breakup of Yugoslavia, a rise in national awareness has caused individuals to modify their speech according to newly established standard-language guidelines. The wars have caused large migrations, changing the ethnic (and dialectal) picture of some areas—especially in Bosnia and Herzegovina, but also in central Croatia and Serbia (Vojvodina in particular). In some areas, it is unclear whether location or ethnicity is the dominant factor in the dialect of the speaker. Because of this the speech patterns of some communities and regions are in a state of flux, and it is difficult to determine which dialects will die out entirely. Further research over the next few decades will be necessary to determine the changes made in the dialectical distribution of this language group.

Relationships among languages and dialects

The table below illustrates relationships among the languages and dialects of the western group of South Slavic languages:

| Dialect | Subdialect | Bulgarian | Macedonian | Serbo-Croatian | Slovene | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serbian | Montenegrin | Bosnian | Croatian | |||||

| Torlakian | x | x | x | |||||

| Shtokavian | Kosovo–Resava | x | ||||||

| Šumadija–Vojvodina | x | |||||||

| Zeta-South Raška | x | x | x | |||||

| Eastern Herzgovinian | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Eastern Bosnian | x | x | ||||||

| Western Ikavian | x | x | ||||||

| Slavonian | x | |||||||

| Chakavian | x | |||||||

| Kajkavian | x | x | ||||||

Shtokavian dialect

The eastern Herzegovinian dialect is the basis of the Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin, and Serbian standard variants of the pluricentric Serbo-Croatian.[15]

Slavomolisano

The Slavomolisano dialect is spoken in three villages of the Italian region of Molise by the descendants of South Slavs who migrated from the eastern Adriatic coast during the 15th century. Because this group left the rest of their people so long ago, their diaspora language is distinct from the standard language and influenced by Italian. However, their dialect retains archaic features lost by all other Štokavian dialects after the 15th century, making it a useful research tool.

Chakavian dialects

Chakavian is spoken in the western, central, and southern parts of Croatia—mainly in Istria, the Kvarner Gulf, Dalmatia and inland Croatia (Gacka and Pokupje, for example). The Chakavian reflex of proto-Slavic yat is i or sometimes e (rarely as (i)je), or mixed (Ekavian–Ikavian). Many dialects of Chakavian preserved significant number of Dalmatian words, but also have many loanwords from Venetian, Italian, Greek and other Mediterranean languages.

Example: Ča je, je, tako je vavik bilo, ča će bit, će bit, a nekako će već bit!

Burgenland Croatian

This dialect is spoken primarily in the federal state of Burgenland in Austria and nearby areas in Vienna, Slovakia, and Hungary by descendants of Croats who migrated there during the 16th century. This dialect (or family of dialects) differs from standard Croatian, since it has been heavily influenced by German and Hungarian. It has properties of all three major dialectal groups in Croatia, since the migrants did not all come from the same area. The linguistic standard is based on a Chakavian dialect, and (like all Chakavian dialects) is characterized by very conservative grammatical structures: for example, it preserves case endings lost in the Shtokavian base of standard Croatian. At most 100,000 people speak Burgenland Croatian and almost all are bilingual in German. Its future is uncertain, but there is movement to preserve it. It has official status in six districts of Burgenland, and is used in some schools in Burgenland and neighboring western parts of Hungary.

Kajkavian dialect

Kajkavian is mostly spoken in northern and northwest Croatia, including one-third of the country near the Hungarian and Slovenian borders—chiefly around the towns of Zagreb, Varaždin, Čakovec, Koprivnica, Petrinja, Delnice and so on. Its reflex of yat is primarily /e/, rarely diphthongal ije). This differs from that of the Ekavian accent; many Kajkavian dialects distinguish a closed e—nearly ae (from yat)—and an open e (from the original e). It lacks several palatals (ć, lj, nj, dž) found in the Shtokavian dialect, and has some loanwords from the nearby Slovene dialects and German (chiefly in towns).

Example: Kak je, tak je; tak je navek bilo, kak bu tak bu, a bu vre nekak kak bu!

Slovene dialects

Grammar

Eastern–Western division

In broad terms, the Eastern dialects of South Slavic (Bulgarian and Macedonian) differ most from the Western dialects in the following ways:

- The Eastern dialects have almost completely lost their noun declensions, and have become entirely analytic.[16]

- The Eastern dialects have developed definite-article suffixes similar to the other languages in the Balkan Sprachbund.[17]

- The Eastern dialects have lost the infinitive; thus, the first-person singular (for Bulgarian) or the third-person singular (for Macedonian) are considered the main part of a verb. Sentences which would require an infinitive in other languages are constructed through a clause in Bulgarian, искам да ходя (iskam da hodya), "I want to go" (literally, "I want that I go").

Apart from these three main areas there are several smaller, significant differences:

- The Western dialects have three genders in both singular and plural (Slovene has dual—see below), while the Eastern dialects only have them in the singular—for example, Serbian on (he), ona (she), ono (it), oni (they, masc), one (they, fem), ona (they, neut); the Bulgarian te (they) and Macedonian тие (tie, 'they') covers the entire plural.

- Inheriting a generalization of another demonstrative as a base form for the third-person pronoun which already occurred in late proto-Slavic, standard literary Bulgarian (like Old Church Slavonic) does not use the Slavic "on-/ov-" as base forms like on, ona, ono, oni (he, she, it, they), and ovaj, ovde (this, here), but uses "to-/t-"based pronouns like toy, tya, to, te, and tozi, tuk (it only retains onzi – "that" and its derivatives). Western Bulgarian dialects and Macedonian have "ov-/on-" pronouns, and sometimes use them interchangeably.

- All dialects of Serbo-Croatian contain the concept of "any" – e.g. Serbian neko "someone"; niko "no one"; iko "anyone". All others lack the last, and make do with some- or no- constructions instead.[18]

Divisions within Western dialects

- While Serbian, Bosnian and Croatian Shtokavian dialects have basically the same grammar, its usage is very diverse. While all three languages are relatively highly inflected, the further east one goes the more likely it is that analytic forms are used – if not spoken, at least in the written language. A very basic example is:

- Croatian – hoću ići – "I want – to go"

- Serbian – hoću da idem – "I want – that – I go"

- Slovene has retained the proto-Slavic dual number (which means that it has nine personal pronouns in the third person) for both nouns and verbs. For example:

- nouns: volk (wolf) → volkova (two wolves) → volkovi (some wolves)

- verbs: hodim (I walk) → hodiva (the two of us walk) → hodimo (we walk)

Divisions within Eastern dialects

- In Macedonian, the perfect is largely based on the verb "to have" (as in other Balkan languages like Greek and Albanian, and in English), as opposed to the verb "to be", which is used as the auxiliary in all other Slavic languages (see also Macedonian verbs):

- Macedonian – imam videno – I have seen (imam – "to have")

- Bulgarian – vidyal sum – I have seen (sum – "to be")

- In Macedonian there are three types of definite article (base definite form, definite noun near the speaker and definite noun far from the speaker).

- дете (dete, 'а child')

- детето (deteto, 'the child')

- детево (detevo, 'this child [near me]')

- детено (deteno, 'that child [over there]')

Writing systems

Languages to the west of Serbia use the Latin script, whereas those to the east and south use Cyrillic. Serbian officially uses the Cyrillic script, though commonly Latin and Cyrillic are used equally. Most newspapers are written in Cyrillic and most magazines are in Latin; books written by Serbian authors are written in Cyrillic, whereas books translated from foreign authors are usually in Latin, other than languages that already use Cyrillic, most notably Russian. On television, writing as part of a television programme is usually in Cyrillic, but advertisements are usually in Latin. The division is partly based on religion – Serbia, Montenegro, Bulgaria and Macedonia (which use Cyrillic) are Orthodox countries, whereas Croatia and Slovenia (which use Latin) are Catholic[19] The Bosnian language, used by the Muslim Bosniaks, also uses Latin, but in the past they used Cyrillic. The Glagolitic alphabet was also used in the Middle Ages (most notably in Bulgaria, Macedonia and Croatia), but gradually disappeared.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "South Slavic". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Friedman, Victor (1999). Linguistic emblems and emblematic languages: on language as flag in the Balkans. Kenneth E. Naylor memorial lecture series in South Slavic linguistics ; vol. 1. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State University, Dept. of Slavic and East European Languages and Literatures. p. 8. OCLC 46734277.

- ↑ Alexander, Ronelle (2000). In honor of diversity: the linguistic resources of the Balkans. Kenneth E. Naylor memorial lecture series in South Slavic linguistics ; vol. 2. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State University, Dept. of Slavic and East European Languages and Literatures. p. 4. OCLC 47186443.

- ↑ Roland Sussex (2006). The Slavic languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-521-22315-7.

- ↑ Cited after Matasović (2008:59, 143)

- ↑ Kordić 2010, p. 75.

- ↑ Friedman, Victor (2003). "Language in Macedonia as an Identity Construction Site". In Brian, D. Joseph; et al. When Languages Collide: Perspectives on Language Conflict, Language Competition, and Language Coexistence. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. pp. 261–262. OCLC 50123480.

- ↑ Kordić 2010, pp. 77–90.

- ↑ Bunčić, Daniel (2008). "Die (Re-)Nationalisierung der serbokroatischen Standards" [The (Re-)Nationalisation of Serbo-Croatian Standards]. In Kempgen, Sebastian. Deutsche Beiträge zum 14. Internationalen Slavistenkongress, Ohrid, 2008. Welt der Slaven (in German). Munich: Otto Sagner. p. 93. OCLC 238795822.

- ↑ Gröschel, Bernhard (2009). Das Serbokroatische zwischen Linguistik und Politik: mit einer Bibliographie zum postjugoslavischen Sprachenstreit [Serbo-Croatian Between Linguistics and Politics: With a Bibliography of the Post-Yugoslav Language Dispute]. Lincom Studies in Slavic Linguistics ; vol 34 (in German). Munich: Lincom Europa. p. 265. ISBN 978-3-929075-79-3. LCCN 2009473660. OCLC 428012015. OL 15295665W.

- ↑ Кочев (Kochev), Иван (Ivan) (2001). Български диалектен атлас (Bulgarian dialect atlas) (in Bulgarian). София: Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. ISBN 954-90344-1-0. OCLC 48368312.

- 1 2 Fortson, Benjamin W. (2009-08-31). Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction Blackwell textbooks in linguistics. John Wiley and Sons. p. 431. ISBN 1-4051-8896-0. Retrieved 2015-11-19.

- ↑ van Wijk, Nicolaas (1956). Les Langues Slaves [The Slavic Languages] (in French) (2nd ed.). Mouton & Co - 's-Gravenhage.

- ↑ Balkan Syntax and Semantics, John Benjamins Publishing, 2004, ISBN 158811502X, The typology of Balkan evidentiality and areal linguistics , Victor Friedman, p. 123.

- ↑ Kordić, Snježana (2003). "Glotonim "srbohrvaški jezik" glede na "srbski, hrvaški, bosanski, črnogorski"" [The glotonym "Serbo-Croatian" vs. "Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian, Montenegrin"] (PDF). Slavistična revija (in Slovenian). 51 (3): 355–364. ISSN 0350-6894. COBISS 23508578. Archived from the original on 8 August 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ↑ Note that some remnants of cases do still exist in Bulgarian – see here.

- ↑ In Macedonian, these are especially well-developed, also taking on a role similar to demonstrative pronouns:

- Bulgarian : stol – "chair" → stolat – "the chair"

- Macedonian : stol – "chair" → stolot – "the chair" → stolov – "this chair here" → stolon – "that chair there". As well as these, Macedonian also has a separate set of demonstratives: ovoj stol – "this chair"; onoj stol – "that chair".

- ↑ In Bulgarian, more complex constructions such as "koyto i da bilo" ("whoever it may be" ≈ "anyone") can be used if the distinction is necessary.

- ↑ This distinction is true for the whole Slavic world: the Orthodox Russia, Ukraine and Belarus also use Cyrillic, as does Rusyn (Eastern Orthodox/Eastern Catholic), whereas the Catholic Poland, Czech Republic and Slovakia use Latin, as does Sorbian. Romania and Moldova, which are not Slavic but are Orthodox, also used Cyrillic until 1860 and 1989, respectively, and it is still used in Transdnistria.

Sources

- Kordić, Snježana (2010). Jezik i nacionalizam [Language and Nationalism] (PDF). Rotulus Universitas (in Serbo-Croatian). Zagreb: Durieux. p. 430. ISBN 978-953-188-311-5. LCCN 2011520778. OCLC 729837512. OL 15270636W. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- Matasović, Ranko (2008), Poredbenopovijesna gramatika hrvatskoga jezika (in Serbo-Croatian), Zagreb: Matica hrvatska, ISBN 978-953-150-840-7

- Sussex, Roland; Cubberly, Paul (2006), The Slavic languages, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-511-24204-5

- Edward Stankiewicz (1986). The Slavic Languages: Unity in Diversity. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-009904-1.

- Mila Dimitrova-Vulchanova (1998). Formal Approaches to South Slavic Languages. Linguistics Department, NTNU.

- Mirjana N. Dedaic; Mirjana Miskovic-Lukovic (2010). South Slavic Discourse Particles. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 90-272-5601-2.

- Mila Dimitrova-Vulchanova; Lars Hellan (15 March 1999). Topics in South Slavic Syntax and Semantics. John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 978-90-272-8386-3.

- Radovan Lučić (2002). Lexical norm and national language: lexicography and language policy in South-Slavic languages after 1989. Verlag Otto Sagner.

- Motoki Nomachi (2011). The Grammar of Possessivity in South Slavic Languages: Synchronic and Diachronic Perspectives. Slavic Research Center, Hokkaido University. ISBN 978-4-938637-66-8.

- Steven Franks; Brian D. Joseph; Vrinda Chidambaram (1 January 2009). A Linguist's Linguist: Studies in South Slavic Linguistics in Honor of E. Wayles Browne. Slavica Publishers. ISBN 978-0-89357-364-5.

- A. A. Barentsen; R. Sprenger; M. G. M. Tielemans (1982). South Slavic and Balkan Linguistics. Rodopi. ISBN 90-6203-634-1.

- Anita Peti-Stantic; Mateusz-Milan Stanojevic; Goranka Antunovic (2015). Language Varieties Between Norms and Attitudes: South Slavic Perspectives : Proceedings from the 2013 CALS Conference. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-631-66256-4.

Further reading

- Тохтасьев, С.Р. (1998), "Древнейшие свидетельства славянского языка на Балканах. Основы балканского языкознания. Языки балканского региона", Ч, 2

- Golubović, J. and Gooskens, C. (2015), "Mutual intelligibility between West and South Slavic languages", Russian Linguistics, 39 (3): 351–373

- Henrik Birnbaum (1976). On the significance of the second South Slavic influence for the evolution of the Russian literary language. Peter de Rider Press. ISBN 978-90-316-0047-2.

- Masha Belyavski-Frank (2003). The Balkan conditional in South Slavic: a semantic and syntactic study. Sagner.

- Patrice Marie Rubadeau (1996). A descriptive study of clitics in four Slavic languages: Serbo-Croatian, Bulgarian, Polish, and Czech. University of Michigan.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to South Slavic languages. |