Roller coaster

A roller coaster is a type of amusement ride that employs a form of elevated railroad track designed with tight turns, steep slopes, and sometimes inversions.[1] People ride along the track in open cars, and the rides are often found in amusement parks and theme parks around the world.[1] LaMarcus Adna Thompson obtained one of the first known patents for a roller coaster design in 1885, related to the Switchback Railway that opened a year earlier at Coney Island.[2][3] The track in a coaster design does not necessarily have to be a complete circuit, as shuttle roller coasters demonstrate. Most roller coasters have multiple cars in which passengers sit and are restrained.[4] Two or more cars hooked together are called a train. Some roller coasters, notably wild mouse roller coasters, run with single cars.

History

The Russian mountain and the Aerial Promenades

The oldest roller coasters are believed to have originated from the so-called "Russian Mountains", specially constructed hills of ice located in the area that is now St. Petersburg.[5] Built in the 17th century, the slides were built to a height of between 21 and 24 m (70 and 80 feet), had a 50-degree drop, and were reinforced by wooden supports. Later, in 1784, Catherine the Great is said to have constructed a sledding hill in the gardens of her palace at Oranienbaum in St. Petersburg.[6] The name Russian Mountains to designate a roller coaster is preserved in many languages (e.g. the Spanish montaña rusa), but the Russian term for roller coasters is американские горки ("amerikanskiye gorki"), meaning "American mountains."

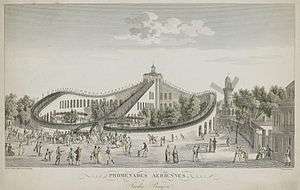

The first modern roller coaster, the Promenades Aeriennes, opened in Parc Beaujon in Paris on July 8, 1817.[7] It featured wheeled cars securely locked to the track, guide rails to keep them on course, and higher speeds.[8] It spawned half a dozen imitators, but their popularity soon declined.

However, during the Belle Epoque they returned to fashion. In 1887 French entrepreneur Joseph Oller, co-founder of the Moulin Rouge music hall, constructed the Montagnes Russes de Belleville, "Russian Mountains of Belleville" with two hundred meters of track laid out in a double-eight, later enlarged to four figure-eight-shaped loops.[9]

Scenic railways

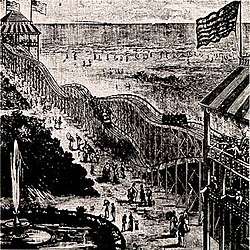

In 1827, a mining company in Summit Hill, Pennsylvania constructed the Mauch Chunk Switchback Railway, a downhill gravity railroad used to deliver coal to Mauch Chunk, Pennsylvania – now known as Jim Thorpe.[10] By the 1850s, the "Gravity Road" (as it became known) was selling rides to thrill seekers. Railway companies used similar tracks to provide amusement on days when ridership was low.

Using this idea as a basis, LaMarcus Adna Thompson began work on a gravity Switchback Railway that opened at Coney Island in Brooklyn, New York, in 1884.[11] Passengers climbed to the top of a platform and rode a bench-like car down the 600-foot (183 m) track up to the top of another tower where the vehicle was switched to a return track and the passengers took the return trip.[12] This track design was soon replaced with an oval complete circuit.[8] In 1885, Phillip Hinkle introduced the first full-circuit coaster with a lift hill, the Gravity Pleasure Road, which became the most popular attraction at Coney Island.[8] Not to be outdone, in 1886 Thompson patented his design of roller coaster that included dark tunnels with painted scenery. "Scenic Railways" were soon found in amusement parks across the county.[8]

Popularity, decline and revival

By 1919, the first underfriction roller coaster had been developed by John Miller.[13] Soon, roller coasters spread to amusement parks all around the world. Perhaps the best known historical roller coaster, Cyclone, was opened at Coney Island in 1927.

The Great Depression marked the end of the golden age of roller coasters, and theme parks in general went into decline. This lasted until 1972, when the instant success of The Racer at Kings Island near Cincinnati began a roller coaster renaissance which has continued to this day.

Steel

In 1959, Disneyland introduced a design breakthrough with Matterhorn Bobsleds, the first roller coaster to use a tubular steel track. Unlike wooden coaster rails, tubular steel can be bent in any direction, allowing designers to incorporate loops, corkscrews, and many other maneuvers into their designs. Most modern roller coasters are made of steel, although wooden coasters and hybrids are still being built.

Etymology

There are several explanations of the name roller coaster. It is said to have originated from an early American design where slides or ramps were fitted with rollers over which a sled would coast.[8] This design was abandoned in favor of fitting the wheels to the sled or other vehicles, but the name endured.

Another explanation is that it originated from a ride located in a roller skating rink in Haverhill, Massachusetts in 1887. A toboggan-like sled was raised to the top of a track which consisted of hundreds of rollers. This Roller Toboggan then took off down gently rolling hills to the floor. The inventors of this ride, Stephen E. Jackman and Byron B. Floyd, claim that they were the first to use the term "roller coaster".[12]

The term jet coaster is used for roller coasters in Japan, where such amusement park rides are very popular.[14]

In many languages, the name refers to "Russian mountains". Contrastingly, in Russian, they are called "American mountains". In Scandinavian languages and German, the roller coaster is referred as "mountain-and-valley railway". German also knows the word "Achterbahn", stemming from "Figur-8-Bahn", like Dutch "Achtbaan", relating to the form of the number 8 ("acht" in German and also Dutch).

Mechanics

The cars on a typical roller coaster are not self-powered. Instead, a standard full circuit coaster is pulled up with a chain or cable along the lift hill to the first peak of the coaster track. The potential energy accumulated by the rise in height is transferred to kinetic energy as the cars race down the first downward slope. Kinetic energy is then converted back into potential energy as the train moves up again to the second peak. This hill is necessarily lower, as some mechanical energy is lost to friction.

Not all rides feature a lift hill, however. The train may be set into motion by a launch mechanism such as a flywheel launch, linear induction motors, linear synchronous motors, hydraulic launch, compressed air launch or drive tire. Such launched coasters are capable of reaching higher speeds in a shorter length of track than those featuring a conventional lift hill. Some roller coasters move back and forth along the same section of track; these are known as shuttles and usually run the circuit once with riders moving forwards and then backwards through the same course.

A properly designed ride under good conditions will have enough kinetic, or moving, energy to complete the entire course, at the end of which brakes bring the train to a complete stop and it is pushed into the station. A brake run at the end of the circuit is the most common method of bringing the roller coaster ride to a stop. One notable exception is a powered roller coaster. These rides, instead of being powered by gravity, use one or more motors in the cars to propel the trains along the course.

If a continuous-circuit coaster does not have enough kinetic energy to completely travel the course after descending from its highest point (as can happen with high winds or increased friction), the train can valley: that is, roll backwards and forwards along the track, until all kinetic energy has been released. The train will then come to a complete stop in the middle of the track. This, however, works somewhat differently on a launched coaster. When a train launcher does not have enough potential energy to launch the train to the top of an incline, the train is said to roll back.

In 2006, NASA announced that it would build a system using principles similar to those of a roller coaster to help astronauts escape the Ares I launch pad in an emergency[15], although this has since been scrapped along with the rest of the Ares program.

Safety

Many safety systems are implemented in roller coasters. One of these is the block system. Most large roller coasters have the ability to run two or more trains at once, and the block system prevents these trains from colliding. In this system, the track is divided into several sections, or blocks. Only one train at a time is permitted in each block. At the end of each block, there is a section of track where a train can be stopped if necessary (either by preventing dispatch from the station, closing brakes, or stopping a lift). Sensors at the end of each block detect when a train passes so that the computer running the ride is aware of which blocks are occupied. When the computer detects a train about to travel into an already occupied block, it uses whatever method is available to keep it from entering. The trains are fully automated.

The above can cause a cascade effect when multiple trains become stopped at the end of each block. In order to prevent this problem, ride operators follow set procedures regarding when to release a newly loaded train from the station. One common pattern, used on rides with two trains, is to do the following: hold train #1 (which has just finished the ride) right outside the station, release train #2 (which has loaded while #1 was running), and then allow #1 into the station to unload safely.

Another key to safety is the control of the roller coaster's operating computers: programmable logic controllers (often called PLCs). A PLC detects faults associated with the mechanism and makes decisions to operate roller coaster elements (e.g. lift, track-switches and brakes) based on configured state and operator actions. Periodic maintenance and inspection are required to verify structures and materials are within expected wear tolerances and are in sound working order. Sound operating procedures are also a key to safety.

Roller coaster design requires a working knowledge of basic physics to avoid uncomfortable, even potentially fatal, strain to the rider. Ride designers must carefully ensure the accelerations experienced throughout the ride do not subject the human body to more than it can handle. The human body needs time to detect changes in force in order to control muscle tension. Failure to take this into account can result in severe injuries such as whiplash. The accelerations accepted in roller coaster design are generally in the 4-6Gs (40–60 m s−2) range for positive vertical (pushing you into your seat), and 1.5-2Gs (15–20 m s−2) for the negative vertical (flying out of your seat as you crest a hill). This range safely ensures the majority of the population experiences no harmful side effects. Lateral accelerations are generally kept to a minimum by banking curves. The neck's inability to deal with high forces leads to lateral accelerations generally limited to under 1.8Gs. Sudden accelerations in the lateral plane result in a rough ride.

Despite safety measures, accidents can, and do, occur.[16] Regulations concerning accident reporting vary from one authority to another. Thus in the US, California requires amusement parks to report any ride-related accident that requires an emergency room visit, while Florida exempts parks whose parent companies employ more than 1000 people from having to report any accidents at all. Rep. Ed Markey of Massachusetts has introduced legislation that would give oversight of rides to the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC).

Ride accidents can also be caused by riders themselves or ride operators not following safety directions properly, and, in extremely rare cases, riders can be injured by mechanical failures. In recent years, controversy has arisen about the safety of increasingly extreme rides. There have been suggestions that these may be subjecting passengers to translational and rotational accelerations that may be capable of causing brain injuries. In 2003 the Brain Injury Association of America concluded in a report that "There is evidence that roller coaster rides pose a health risk to some people some of the time. Equally evident is that the overwhelming majority of riders will suffer no ill effects."[17]

A similar report in 2005 linked roller coasters and other thrill rides with potentially triggering abnormal heart conditions that could lead to death.[18] Autopsies have shown that recent deaths at various Disney parks, Anheuser-Busch parks, and Six Flags parks were due to previously undetected heart ailments.

Statistically, roller coasters are very safe compared to other activities. The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission estimates that 134 park guests required hospitalization in 2001 and that fatalities related to amusement rides average two per year. According to a study commissioned by Six Flags, 319 million people visited parks in 2001. The study concluded that a visitor has a one in one-and-a-half billion chance of being fatally injured, and that the injury rates for children's wagons, golf carts, and folding lawn chairs are higher than for amusement rides.[19]

Types

Roller coasters are divided into two main categories: steel roller coasters and wooden roller coasters. Steel coasters have tubular steel tracks, and compared to wooden coasters, they are typically known for offering a smoother ride and their ability to turn riders upside-down. Wooden coasters have flat steel tracks, and are typically renowned for producing "air time" through the use of negative G-forces when reaching the crest of some hill elements. Newer types of track, such as I-Box and Topper introduced by Rocky Mountain Construction, improve the ride experience on wooden coasters, lower maintenance costs, and add the ability to invert riders.

Modern roller coasters are constantly evolving to provide a variety of different experiences. More focus is being placed on the position of riders in relation to the overall experience. Traditionally, riders sit facing forward, but newer variations such as stand-up and flying models position the rider in different ways to change the experiences. A flying model, for example, is a suspended roller coaster where the riders lie facing forward and down with their chests and feet strapped in. Other ways of enhancing the experience involve removing the floor beneath passengers riding above the track, as featured in floorless roller coasters. Also new track elements – usually types of inversions – are often introduced to provide entirely new experiences.

By height

Several height classifications have been used by parks and manufacturers in marketing their roller coasters, as well as enthusiasts within the industry. One classification, the kiddie coaster, is a roller coaster specifically designed for younger riders. Following World War II, parks began pushing for more of them to be built in contrast to the height and age restrictions of standard designs at the time. Companies like Philadelphia Toboggan Company (PTC) developed scaled-down versions of their larger models to accommodate the demand. These typically featured lift hills smaller than 25 feet (7.6 m), and still do today. The rise of kiddie coasters soon led to the development of "junior" models that had lift hills up to 45 feet (14 m). A notable example of a junior coaster is the Sea Dragon – the oldest operating roller coaster from PTC's legendary designer John Allen – which opened at Wyandot Lake in 1956 near Powell, Ohio.[12]

A hypercoaster, occasionally stylized as hyper coaster, is a type of roller coaster with a height or drop of at least 200 feet (61 m). Moonsault Scramble, which debuted at Fuji-Q Highland in 1984, was the first to break this barrier, though the term hypercoaster was first coined by Cedar Point and Arrow Dynamics with the opening of Magnum XL-200 in 1989.[20][21] Hypercoasters have become one of the most predominant types of roller coasters in the world, now led by manufacturers Bolliger & Mabillard and Intamin.

A giga coaster is a type of roller coaster with a height or drop of at least 300 feet (91 m).[22] The term was coined during a partnership between Cedar Point and Intamin on the construction of Millennium Force.[23][24] Although Morgan and Bolliger & Mabillard have not used the term giga,[25] both have also produced roller coasters in this class.

| Name | Park | Manufacturer | Status | Opened | Height |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Millennium Force | Cedar Point | Intamin | Operating | May 13, 2000 | 310 feet (94 m) |

| Steel Dragon 2000 | Nagashima Spa Land | Morgan | Operating | August 1, 2000 | 318 feet (97 m) |

| Intimidator 305 | Kings Dominion | Intamin | Operating | April 2, 2010 | 305 feet (93 m) |

| Leviathan | Canada's Wonderland | Bolliger & Mabillard | Operating | May 6, 2012 | 306 feet (93 m) |

| Fury 325 | Carowinds | Bolliger & Mabillard | Operating | March 25, 2015[26] | 325 feet (99 m) |

| Red Force | Port Aventura World | Intamin | Operating | April 7, 2017[27] | 367 feet (112 m) |

A strata coaster is a type of roller coaster with a height or drop of at least 400 feet (120 m).[22] As with the other two height classifications, the term strata was first introduced by Cedar Point with the release of Top Thrill Dragster, a 420-foot-tall (130 m) roller coaster that opened in 2003.[28] Another strata coaster, Kingda Ka, opened at Six Flags Great Adventure in 2005 as the tallest roller coaster in the world featuring a height of 456 feet (139 m). Superman: Escape From Krypton exceeded 400 feet (120 m) back when it opened in 1997, but its shuttle coaster design where the trains fail to travel a complete circuit usually prevents the roller coaster from being classified in the same category.[28][29]

| Name | Park | Manufacturer | Status | Opened | Height |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top Thrill Dragster | Cedar Point | Intamin | Operating | May 4, 2003 | 420 feet (130 m) |

| Kingda Ka | Six Flags Great Adventure | Intamin | Operating | May 21, 2005 | 456 feet (139 m) |

Major roller coaster manufacturers

- Allan Herschell Company (defunct)

- Arrow Development

- Arrow Dynamics (bought by S&S Power, renamed S&S Arrow then S&S Worldwide)

- B.A. Schiff & Associates

- Bolliger & Mabillard

- Bradley and Kaye (defunct)

- Chance Morgan (formerly D. H. Morgan Manufacturing)

- Chance Rides

- Custom Coasters International (defunct)

- D. H. Morgan Manufacturing

- Dinn Corporation (defunct)

- Dynamic Structures

- E&F Miler Industries

- Fabbri Group

- Gerstlauer

- Giovanola (defunct)

- The Gravity Group

- Great Coasters International

- Hopkins Rides

- Intamin

- Mack Rides

- Maurer Söhne

- Martin & Vleminckx

- Philadelphia Toboggan Coasters

- Pinfari (defunct)

- Premier Rides

- Preston & Barbieri

- Rocky Mountain Construction

- Roller Coaster Corporation of America

- Sansei Technologies

- S&S - Sansei Technologies (formerly known as S&S Worldwide)

- Schwarzkopf (defunct)

- TOGO (defunct)

- Vekoma

- Zamperla

- Zierer

Gallery

- Roller Coasters

.jpg) Riding Fahrenheit, located at Hersheypark in Hershey, Pennsylvania.

Riding Fahrenheit, located at Hersheypark in Hershey, Pennsylvania. Hypersonic XLC, the world's first production Thrust Air 2000 (now defunct)

Hypersonic XLC, the world's first production Thrust Air 2000 (now defunct)_01.jpg) Top Thrill Dragster at Cedar Point is the first strata coaster ever built.

Top Thrill Dragster at Cedar Point is the first strata coaster ever built. Riding Expedition GeForce at Holiday Park, Germany.

Riding Expedition GeForce at Holiday Park, Germany. Raptor, a steel inverted coaster, is located at Cedar Point in Sandusky, Ohio.

Raptor, a steel inverted coaster, is located at Cedar Point in Sandusky, Ohio. New Texas Giant at Six Flags Over Texas before being refurbished into a hybrid steel-wood coaster.

New Texas Giant at Six Flags Over Texas before being refurbished into a hybrid steel-wood coaster. Lightning Racer at Hersheypark is a racing, dueling roller coaster made by GCI.

Lightning Racer at Hersheypark is a racing, dueling roller coaster made by GCI.- This all-wooden roller coaster, built in 1951, dominates the Linnanmäki amusement park in Helsinki, Finland.

- Coney Island Cyclone in Brooklyn, New York was built in 1927 and refurbished in 1975.

Son of Beast in Kings Island was the only wooden coaster to have a vertical loop. The loop was removed in 2006, and the ride was closed from 2009 until its demolition in 2012.

Son of Beast in Kings Island was the only wooden coaster to have a vertical loop. The loop was removed in 2006, and the ride was closed from 2009 until its demolition in 2012.- Jack Rabbit at Kennywood Park outside of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania was built in 1920.

- Phoenix, built in 1947, at Knoebles Grove in Elysburg, Pennsylvania. It was relocated from San Antonio's Playland Park in 1984.

- Oblivion at Alton Towers in Staffordshire, England.

- Griffon splashing down into a pool at Busch Gardens Williamsburg.

Great Bear is the first steel inverted coaster in Pennsylvania, located at Hersheypark.

Great Bear is the first steel inverted coaster in Pennsylvania, located at Hersheypark._06.jpg) Behemoth, at Canada's Wonderland, was the highest (70 m or 230 ft) and fastest (124 km/h or 77 mph) coaster in Canada before Leviathan opened.

Behemoth, at Canada's Wonderland, was the highest (70 m or 230 ft) and fastest (124 km/h or 77 mph) coaster in Canada before Leviathan opened.

Black Mamba at Phantasialand, Germany

Black Mamba at Phantasialand, Germany Euro-Mir, a spinning roller coaster at Europa-Park in Rust, Germany

Euro-Mir, a spinning roller coaster at Europa-Park in Rust, Germany Dragon Khan at PortAventura in Salou (Tarragona), Spain

Dragon Khan at PortAventura in Salou (Tarragona), Spain- Thunderbolt at Kennywood outside of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania was built in 1968.

Leviathan, also at Canada's Wonderland, is the current biggest coaster in Canada (93 m or 306 ft, 148 km/h or 92 mph) and is also made by Bolliger & Mabillard. It is the second biggest coaster before Fury 325 at Carowinds over 91 m (300 ft) made by B&M.

Leviathan, also at Canada's Wonderland, is the current biggest coaster in Canada (93 m or 306 ft, 148 km/h or 92 mph) and is also made by Bolliger & Mabillard. It is the second biggest coaster before Fury 325 at Carowinds over 91 m (300 ft) made by B&M. Kingda Ka is the world's tallest roller coaster and is the second strata coaster in the world after Top Thrill Dragster.

Kingda Ka is the world's tallest roller coaster and is the second strata coaster in the world after Top Thrill Dragster.

See also

- Amusement park (List of amusement parks)

- Euthanasia Coaster

- RollerCoaster Tycoon

- Thrillville: Off the Rails – video game with roller coaster design simulator

- List of roller coaster rankings

- Train (roller coaster)

References

- 1 2 "Definition of roller coaster in English". Oxford Living Dictionaries. Retrieved May 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Gravity switch-back railway; US patent# 332762". Google.com. Retrieved May 28, 2017.

- ↑ "First roller coaster in America opens - Jun 16, 1884 - HISTORY.com". HISTORY.com. Retrieved 2016-12-30.

- ↑ "Roller Coaster Glossary - Roller Coasters". www.ultimaterollercoaster.com.

- ↑ Robert Coker (2002). Roller Coasters: A Thrill Seeker's Guide to the Ultimate Scream Machines. New York: Metrobooks. 14. ISBN 1-58663-172-1.

- ↑ David Bennett (1998). Roller Coaster: Wooden and Steel Coasters, Twisters and Corkscrews. Edison, New Jersey: Chartwell Books. 9. ISBN 0-7865-0885-X.

- ↑ Fierro, Alfred, Histoire et Dictionnaire de Paris p. 613

- 1 2 3 4 5 Urbanowicz, Steven J. (2002). The Roller Coaster Lover's Companion; Citadel Press, Kensington, New York. ISBN 0-8065-2309-3.

- ↑ Valérie RANSON-ENGUIALE, « Promenades aériennes », Histoire par l'image [en ligne], consulté le 26 Mai 2017. URL : http://www.histoire-image.org/etudes/promenades-aeriennes

- ↑ "Roller Coaster History: Early Years In America". Retrieved on July 26, 2007.

- ↑ Chris Sheedy (2007-01-07). "Icons — In the Beginning... Roller-Coaster". The Sun-Herald Sunday Life (Weekly Supplement). John Fairfax Publications Pty Ltd. p. 10.

- 1 2 3 Rutherford, Scott (2004). The American Roller Coaster. MBI. ISBN 0760319294.

- ↑ "Patent Images". patimg2.uspto.gov.

- ↑ Robb and Elissa Alvey. "Theme Park Review: Japan 2004", themeparkreview.com. Retrieved on March 18, 2008.

- ↑ Chris Bergin (November 3, 2006). "NASA will build Rollercoaster for Ares I escape". NASA Spaceflight.com. Archived from the original on 2006-11-15. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

- ↑ "Verified Injury Accidents at Theme and Amusement Parks".

- ↑ Blue Ribbon Panel (2003-02-25). "Blue Ribbon Panel Review of the Correlation between Brain Injury and Roller Coaster Rides — Final Report". Archived from the original on 2006-11-29. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

- ↑ Charlene Laino and Louise Chang, MD (2005-11-16). "Roller Coasters: Safe for the Heart?". WebMD.com. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

- ↑ Arthur Levine. "White Knuckles Are the Worst of It". themeparks.about.com. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

- ↑ Meskil, Paul (August 6, 1989). "A Rolling Revival". New York Daily News. Retrieved August 16, 2017.

- ↑ "Coaster Landmark Award: Magnum XL-200". American Coaster Enthusiasts. Retrieved August 16, 2017.

- 1 2 Murphy, Mekado (August 17, 2015). "Just How Tall Can Roller Coasters Get?". New York Times. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

- ↑ "310-Foot-Tall "Giga-Coaster" Nears End Of Construction". UltimateRollercoaster.com. March 9, 2000. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

- ↑ "Millenium Force". Cedar Point. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

- ↑ "Bolliger & Mabillard - Products". Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ↑ "Fury 325 Media Day Reports from Carowinds Park". Park Journey.

- ↑ "Red Force - Ferrari Land (Salou, Tarragona, Spain)". rcdb.com.

- 1 2 "National Roller Coaster Day: Ten incredible records for every thrill seeker". guinnessworldrecords.com. August 16, 2016. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

- ↑ "Watch the plunge from this new 325-foot roller coaster". USA Today. March 6, 2015. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

External links

- Roller Coaster Glossary

- Roller Coaster History – History of the roller coaster

- Roller Coaster Database – Information, statistics and photos for over 3700 roller coasters throughout the world

- Roller Coaster Patents – With links to the U.S. Patent office

- Roller Coaster Physics – Classic physics explained in terms of roller coasters

- How Roller Coasters Work

- 3D Animated Roller Coaster in MS Excel

- Magic Mountain Announces ‘Twisted’ Plans for Iconic Colossus Roller Coaster