Gaochang

|

قۇچۇ 高昌 | |

| |

Shown within Xinjiang | |

| Location | Xinjiang, China |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 42°51′10″N 89°31′45″E / 42.85278°N 89.52917°ECoordinates: 42°51′10″N 89°31′45″E / 42.85278°N 89.52917°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | In ruins |

Gaochang[1] (Chinese: 高昌; pinyin: Gāochāng; Old Uyghur: قۇچۇ, Qocho), also called Karakhoja, Qara-hoja, Kara-Khoja, or Karahoja (قاراغوجا in Uyghur), is the site of a ruined, ancient oasis city on the northern rim of the inhospitable Taklamakan Desert in present-day Xinjiang, China. The site is also known in published reports as Chotscho, Khocho, Qocho, or Qočo. During the Yuan and Ming dynasties, Gaochang was referred to as "Halahezhuo" (哈拉和卓) (Qara-khoja) and Huozhou.

The ruins are located 30 km southeast of modern Turpan.[2] The archaeological remains are just outside the modern town of Gaochang, at a place called Idykut-schari or Idikutschari by local residents. (see the work of Albert Grünwedel in the external links below). Artistic depictions of the city have been published by Albert von Le Coq. Gaochang is considered in some sources to have been a "Chinese colony",[3][4] that is, it was located in a region otherwise occupied at the time by West Eurasian peoples.

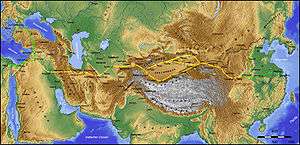

A busy trading center, it was a stopping point for merchant traders traveling on the Silk Road. It was destroyed in wars during the 14th century, and old palace ruins and inside and outside cities can still be seen today.

Near Gaochang is another major archeological site: the Astana tombs.

History

Jushi Kingdom and early Han-Chinese rule

The earliest people known to have lived in the area were the Gushi (or Jushi). The region around Turfan was described during the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) as being occupied by the Jūshī, while control over the region swayed between the Han-Chinese and the Xiongnu.

Gaochang was built in the 1st century BC, it was an important site along the Silk Road. It played a key role as a transportation hub in western China. The Jushi leaders invited the Chinese Han dynasty to take over and pledged their allegiance. In 327, the Gaochang Commandery (jùn) was created by the Former Liang under the Han Chinese ruler Zhang Gui. The Chinese set up a military colony/garrison and organized the land into multiple divisions. Han Chinese colonists from the Hexi region and the central plains also settled in the region.[5]

After the fall of the Western Jin Dynasty, northern China split into multiple states, including the Central Asian oases.[6] Gaochang was ruled by the Former Liang, Former Qin, and Northern Liang as part of a commandery. In 383 The General Lu Guang of the Former Qin seized control of the region.[7]

In 439, remnants of the Northern Liang,[8] led by Juqu Wuhui and Juqu Anzhou, fled to Gaochang where they would hold onto power until 460 when they were conquered by the Rouran Khaganate. Another version of this story says that in 439 a man named Ashina led 500 families from Gansu to Gaochang. In 460, the Rouran forced them to move to the Altai. They became the Ashina clan that formed the Gokturk Khaganate[9]

Six Dynasties Turfan tombs contained dumplings.[10][11]

Rouran, Gaoche, and Göktürk dominance over Gaochang's rulers

From the mid-5th century until the mid-7th century, there existed four independent statelets in the narrow Turpan basin. These were controlled by the Kan clan, Zhang clan, Ma clan, and Qu clan.

A the time of its conquest by the Rouran Khaganate, there were more than ten thousand Han Chinese households in Gaochang.[12] The Rouran Khaganate, which was based in Mongolia, appointed a Han Chinese named Kan Bozhou to rule as King of Gaochang in 460, and it became a separate vassal kingdom of the Khaganate.[13] Kan was dependent on Rouran backing.[14] Yicheng and Shougui were the last two kings of the Chinese Kan family to rule Gaochang.

At this time the Gaoche (高車) was rising to challenge power of the Rouran in the Tarim Basin. The Gaoche king Afuzhiluo (阿伏至羅) killed King Kan Shougui, who was the nephew of Kan Bozhou.[3][15] and appointed a Han from Dunhuang, named Zhang Mengming (張孟明), as his own vassal King of Gaochang.[16][17] Gaochang thus passed under Gaoche rule.

Later, Zhang Mengming was killed in an uprising by the people of Gaochang and replaced by Ma Ru (馬儒). In 501, Ma Ru himself was overthrown and killed, and the people of Gaochang appointed Qu Jia (麴嘉) of Jincheng (in Gansu) as their king. Qu Jia hailed from the Zhong district of Jincheng commandery (金城, roughly corresponding to modern day Lanzhou, Gansu)[15] Qu Jia at first pledged allegiance to the Rouran, but the Rouran khaghan was soon killed by the Gaoche, and he had to submit to Gaoche overlordship. During Qu rule, powerful families established marriage ties with each other and dominated the kingdom, they included the Zhang, Fan, Yin, Ma, Shi, and Xin families. Later, when the Göktürks emerged as the supreme power in the region, the Qu dynasty of Gaochang became vassals of the Göktürks.[18]

While the material civilization of Kucha to its west in this period remained chiefly Indo-Iranian in character, in Goachang it gradually merged into the Tang aesthetics.[19] In 607 the ruler of Gaochang Qu Boya paid tribute to the Sui Dynasty, but his attempt at sinicization provoked a coup which overthrew the Qu ruler.[20] The Qu family was restored six years later, and the successor Qu Wentai welcomed the Tang pilgrim Xuanzang with great enthusiasm in 629 AD.[19]

The Kingdom of Gaochang was made out of Han Chinese colonists and ruled by the Han Chinese[21][22] Qu family which originated from Gansu.[23] Jincheng commandery 金城 (Lanzhou), district of Yuzhong 榆中 was the home of the Qu Jia.[24] The Qu family was linked by marriage alliances to the Turks,[25] with a Turk being the grandmother of King Qu Boya's.[26][27]

Tang rule

However, fearing Tang expansion, Qu Wentai later formed an alliance with the Western Turks and rebelled against Tang suzerainty. Emperor Taizong sent an army led by General Hou Junji against the kingdom in 640, and Qu Wentai apparently died of shock at news of the approaching army.[19] Gaochang was annexed by the Chinese Tang dynasty and turned into a sub-prefecture of Xizhou (西州),[28][29] and the seat of government of Anxi (安西).[18][19] Before the Chinese conquered Gaochang, it was an impediment to Chinese access to Tarim and Transoxiania.[30]

Under Tang rule, Gaochang was inhabited by Chinese, Sogdians, and Tocharians.

7th or 8th century old dumplings and wontons were found in Turfan.[31]

Tang dynasty became greatly weakened due to the An Lushan Rebellion, and in 755, the Chinese were forced to pull back their soldiers from the region. The area was first taken by the Tibetans, then finally by the Uyghurs[32][33][34][35] in 803, who called the area Kocho (Qocho).

Uyghur Kingdom of Qocho

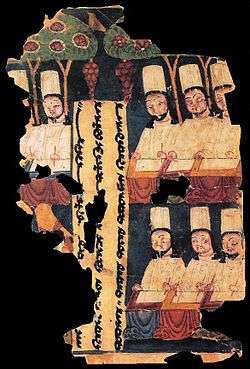

After 840 it then became occupied by remnants of the Uyghur Khaganate fleeing Yenisei Kirghiz invasion of their land.[36] The Uyghurs established the Kingdom of Qocho (Kara-Khoja) in 850. The inhabitants of Qocho practiced Buddhism, Manichaeism and Nestorian Christianity. The Uyghurs converted to Buddhism and sponsored building of temple caves in the nearby Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves where depictions of Uyghur sponsors may be seen. The Buddhist Uyghur kings, who called themselves idiquts, retained their nomadic lifestyle, residing in Qocho during the winter, but moved to the cooler Bishbalik near Urumchi in the summer.[37]

Qocho later became a vassal state of the Kara-Khitans. However, In 1209, the idiqut Barchuq offered Genghis Khan the suzerainty of his kingdom, and went personally to Genghis Khan with a sizeable tribute when demanded in 1211.[38] The Uyghurs thus went into the service of the Mongols,[39] who later formed the Yuan Dynasty in China. The Uyghurs became bureaucrats (semu) of the Mongol Empire and their Uyghur script was modified for Mongolian. As far south as Quanzhou, preponderance of Gaochang Uyghur in Nestorian Christian inscriptions of the Yuan period attests to their importance in the Christian community there.[40]

The Gaochang area was conquered by the Mongols of the Chagatai Khanate (not part of Yuan Dynasty) from 1275 to 1318 by as many as 120,000 troops.

Buddhism

Buddhism spread to China from India along the northern branch of the Silk Road predominantly in the 4th and 5th centuries as the Liang rulers were Buddhists.[41] The building of Buddhist grottos probably began during this period. There are clusters close to Gaochang, the largest being the Bezeklik grottos.[2]

Goachang ruling families

Rulers of the Kan Family

| Family names and given name | Durations of reigns | Era names and their according durations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kàn Bózhōu | 460-477 | Did not exist | |

| Kàn Yìchéng | 477-478 | Did not exist | |

| Kàn Shǒugūi | 478-488? or 478-491? | Did not exist | |

Rulers of the Zhang Family

| Family names and given name | Durations of reigns | Era names and their according durations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zhāng Mèngmíng | 488?-496 or 491?-496 | Did not exist | |

Rulers of the Ma Family

| Family names and given name | Durations of reigns | Era names and their according durations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mǎ Rú | 496-501 | Did not exist | |

Rulers of the Qu Family

| Family names and given name | Durations of reigns | Era names and their according durations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qú Jiā | 501-525 | ||

| Qú Guāng | 525-530 | Ganlu (甘露 Gānlù) 525-530 | |

| Qú Jiān | 530-548 | Zhanghe (章和 Zhānghé) 531-548 | |

| Qú Xuánxǐ | 549-550 | Yongping (永平 Yǒngpíng) 549-550 | |

| unnamed son of Qu Xuanxi | 551-554 | Heping (和平 Hépíng) 551-554 | |

| Qú Bǎomào | 555-560 | Jianchang (建昌 Jiànchāng) 555-560 | |

| Qú Qiángù | 560-601 | Yanchang (延昌 Yánchāng) 561-601 | |

| Qú Bóyǎ[42] | 601-613 619-623 | Yanhe (延和 Yánhé) 602-613 Zhongguang (重光 Zhòngguāng) 620-623 | |

| unnamed usurper | 613-619 | Yihe (Yìhé 義和) 614-619 | |

| Qú Wéntài | 623-640 | Yanshou (延壽 Yánshòu) 624-640 | |

| Qú Zhìshèng | 640 | did not exist | |

Gallery

The road leading in.

The road leading in. The ruins.

The ruins. "Main storage building".

"Main storage building". "Main storage building".

"Main storage building". Manichaean wall painting.

Manichaean wall painting.

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Charles Eliot (4 January 2016). Hinduism and Buddhism: An Historical Sketch. Sai ePublications & Sai Shop. pp. 1075–. GGKEY:4TQAY7XLN48.

- 1 2 "The Silk Road". ess.uci.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-03-15. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

- 1 2 Louis-Frédéric (1977). Encyclopaedia of Asian civilizations, Volume 3. the University of Michigan: L. Frédéric. p. 16. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ↑ Jacques Gernet (1996). A history of Chinese civilization. Cambridge University Press. p. 253. ISBN 0-521-49781-7. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ↑ Ahmad Hasan Dani, ed. (1999). History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume 3. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 304. ISBN 81-208-1540-8. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ↑ Jacques Gernet (1996). A history of Chinese civilization. Cambridge University Press. p. 186. ISBN 0-521-49781-7. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ↑ Society for the Study of Chinese Religions (U.S.), Indiana University, Bloomington. East Asian Studies Center (2002). Journal of Chinese religions, Issues 30-31. the University of California: Society for the Study of Chinese Religions. p. 24. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ↑ Susan Whitfield; British Library (2004). The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. Serindia Publications, Inc. pp. 309–. ISBN 978-1-932476-13-2.

- ↑ Christian, History of Russia, Central Asia and Mongolia, page 449, citing 'Sui annals' and Baumer, History of Central Asia, vol 2, page 174

- ↑ http://www.thedailymeal.com/archaeologists-ancient-dumplings-xinjiang-china/21615

- ↑ http://shanghaiist.com/2016/02/15/1700_year_old_dumplings_found_in_xinjiang.php

- ↑ Ahmad Hasan Dani, ed. (1999). History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume 3. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 305. ISBN 81-208-1540-8. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ↑ Tatsurō Yamamoto, ed. (1984). Proceedings of the Thirty-First International Congress of Human Sciences in Asia and North Africa, Tokyo-Kyoto, 31st August-7th September 1983, Volume 2. Indiana University: Tōhō Gakkai. p. 997. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ↑ Albert E. Dien; Jeffrey K. Riegel; Nancy Thompson Price (1985). Albert E. Dien; Jeffrey K. Riegel; Nancy Thompson Price, eds. Chinese archaeological abstracts: post Han. Volume 4 of Chinese Archaeological Abstracts. the University of Michigan: Institute of Archaeology, University of California, Los Angeles. p. 1567. ISBN 0-917956-54-0. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- 1 2 ROY ANDREW MILLER, ed. (1959). Accounts of Western Nations in the History of the Northern Chou Dynasty. Berkeley and Los Angeles: UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS. p. 5. Retrieved May 17, 2011. East Asia Studies Institute of International Studies University of California CHINESE DYNASTIC HISTORIES TRANSLATIONS No. 6

- ↑ Ahmad Hasan Dani, ed. (1999). History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume 3. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 306. ISBN 81-208-1540-8. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ↑ Tōyō Bunko (Japan). Kenkyūbu (1974). Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko (the Oriental Library), Volumes 32-34. the University of Michigan: The Toyo Bunko. p. 107. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- 1 2 Chang Kuan-ta (1996). Boris Anatol'evich Litvinskiĭ, Zhang, Guang-da, R. Shabani Samghabadi, eds. The crossroads of civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750. UNESCO. p. 306. ISBN 92-3-103211-9. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Rene Grousset (1991). The Empire of the Steppes:A History of Central Asia. Rutgers University Press. pp. 98–99. ISBN 0813513049.

- ↑ Jacques Gernet (1996). A history of Chinese civilization. Cambridge University Press. p. 253. ISBN 0-521-49781-7. Retrieved June 6, 2012.

- ↑ Baij Nath Puri (1987). Buddhism in Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 78–. ISBN 978-81-208-0372-5.

- ↑ Charles Eliot; Sir Charles Eliot (1998). Hinduism and Buddhism: An Historical Sketch. Psychology Press. pp. 206–. ISBN 978-0-7007-0679-2.

- ↑ Marc S. Abramson (31 December 2011). Ethnic Identity in Tang China. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 119–. ISBN 0-8122-0101-9.

- ↑ Roy Andrew Miller (1959). Accounts of Western Nations in the History of the Northern Chou Dynasty [Chou Shu 50. 10b-17b]: Translated and Annotated by Roy Andrew Miller. University of California Press. pp. 5–. GGKEY:SXHP29BAXQY.

- ↑ Valerie Hansen (11 October 2012). The Silk Road. OUP USA. pp. 262–. ISBN 978-0-19-515931-8.

- ↑ Jonathan Karam Skaff (1998). Straddling steppe and town: Tang China's relations with the nomads of inner Asia (640-756). University of Michigan. p. 57.

- ↑ Asia Major. Institute of History and Philology of the Academia Sinica. 1998. p. 87.

- ↑ E. Bretschneider (1876). Notices of the Mediæval Geography and History of Central and Western Asia. Trübner & Company. pp. 122–.

- ↑ Journal of the North-China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. The Branch. 1876. pp. 196–.

- ↑ Jacques Gernet (1996). A history of Chinese civilization. Cambridge University Press. p. 238. ISBN 0-521-49781-7. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ↑ Hansen 2012, p. 11.

- ↑ Matthew Kapstein; Brandon Dotson (20 July 2007). Contributions to the Cultural History of Early Tibet. BRILL. pp. 91–. ISBN 978-90-474-2119-1.

- ↑ Chen (2014).

- ↑ Eighteen Lectures on Dunhuang. BRILL. 7 June 2013. pp. 201–. ISBN 90-04-25233-9.

- ↑ Victor Cunrui Xiong (4 December 2008). Historical Dictionary of Medieval China. Scarecrow Press. pp. 175–. ISBN 978-0-8108-6258-6.

- ↑ Susan Whitfield; British Library (2004). The Silk Road: trade, travel, war and faith (illustrated ed.). Serindia Publications, Inc. p. 309. ISBN 1-932476-13-X. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ↑ Svatopluk Soucek (2000). "Chapter 4 - The Uighur Kingdom of Qocho". A history of Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-65704-0.

- ↑ Biran, Michal. (2005). The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press. p. 75. ISBN 0-521-84226-3.

- ↑ Svatopluk Soucek (2000). "Chapter 7 - The Conquering Mongols". A history of Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-65704-0.

- ↑ The Stones of Zayton speak Archived 2013-10-24 at the Wayback Machine., China Heritage Newsletter, No. 5, March 2006

- ↑ 北凉且渠安周造寺碑 Archived 2011-08-20 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Victor Cunrui Xiong (1 February 2012). Emperor Yang of the Sui Dynasty: His Life, Times, and Legacy. SUNY Press. pp. 206–. ISBN 978-0-7914-8268-1.

Sources

- Bericht über archäologische Arbeiten in Idikutschari und Umgebung im Winter 1902-1903 : vol.1

- Chen Huaiyu (2014), "Religion and Society on the Silk Road: The Inscriptional Evidence from Turfan", Early Medieval China: A Sourcebook, New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 176–194, ISBN 978-0-231-15987-6 .

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gaochang ruins. |

- Along the ancient silk routes: Central Asian art from the West Berlin State Museums, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material from Gaochang

- Online version of Albert Grünwedel's initial work in the area

- Online version of Grünwedel's further work in the area

- Online version of Le Coq's work on monuments of Gaochang