Balochistan

| Balochistan بلوچستان | |

|---|---|

| Region | |

Balochistan region in pink | |

| Countries |

|

| Population (2013) | |

| • Total | c. 18–19 million[1][2][3] |

| Demographics | |

| • Ethnic groups | Baloch |

| • Languages |

Balochi Minor: Brahui, Pashto, Persian, Urdu |

| Largest cities | |

Balōchistān[4] (Balochi: بلوچستان; also Balūchistān or Balūchestān, often interpreted as the Land of the Baloch) is an arid desert and mountainous region in south-western Asia. It comprises the Pakistani province of Balochistan, Iranian province of Sistan and Baluchestan, and the southern areas of Afghanistan including Nimruz, Helmand and Kandahar provinces.[5][6] Balochistan borders the Pashtunistan region to the north, Sindh and Punjab to the east, and Persian regions to the west. South of its southern coastline, including the Makran Coast, are the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Oman.

Etymology

The name "Balochistan" derives from the name of the Baloch people.[5] The term "Baloch" does not appear in pre-Islamic sources. It is likely that the Balochs were known by some other name in their place of origin and that they acquired the name "Baloch" after arriving in Balochistan sometime in the 10th century.[7] The suffix -stān in Baluchi means "place".

Johan Hansman relates the term "Baloch" to Meluḫḫa, the name by which the Indus Valley Civilisation is believed to have been known to the Sumerians (2900–2350 BC) and Akkadians (2334–2154 BC) in Mesopotamia.[8] Meluḫḫa disappears from the Mesopotamian records at the beginning of the second millennium B.C.[9] However, Hansman states that a trace of it in a modified form, as Baluḫḫu, was retained in the names of products imported by the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–605 BC).[10] Al-Muqaddasī, who visited the capital of Makran - Bannajbur, wrote c. 985 AD that it was populated by people called Balūṣī (Baluchi), leading Hansman to postulate "Baluch" as a modification of Meluḫḫa and Baluḫḫu.[11]

Asko Parpola relates the name Meluḫḫa to Indo-Aryan words mleccha (Sanskrit) and milakkha/milakkhu (Pali) etc., which do not have an Indo-European etymology even though they were used to refer to non-Aryan people. Taking them to be proto-Dravidian in origin, he interprets the term as meaning either a proper name milu-akam (from which tamilakam was dervied when the Indus people migrated south) or melu-akam, meaning "high country", a possible reference to Balochistani high lands.[12] Historian Romila Thapar also interprets Meluḫḫa as a proto-Dravidian term, possibly mēlukku, and suggests the meaning "western extremity" (of the Dravidian-speaking regions in the Indian subcontinent). A literal translation into Sanskrit, aparānta, was later used to describe the region by the Indo-Aryans.[13]

During the time of Alexander the Great (356-323 BC), the Greeks called the land Gedrosia and its people Gedrosoi, terms of unknown origin.[14] Using etymological reasoning, H. W. Bailey reconstructs a possible Iranian name, uadravati, meaning "the land of underground channels", which could have been transformed to badlaut in the 9th century and further to balōč in later times. This reasoning remains speculative.[15]

History

The earliest evidence of human occupation in what is now Balochistan is dated to the Paleolithic era, represented by hunting camps and lithic scatters, chipped and flaked stone tools. The earliest settled villages in the region date to the ceramic Neolithic (c. 7000–6000 BCE) and included the site of Mehrgarh in the Kachi Plain. These villages expanded in size during the subsequent Chalcolithic, when interaction was amplified. This involved the movement of finished goods and raw materials, including chank shell, lapis lazuli, turquoise, and ceramics. By 2500 BCE (the Bronze Age), the region now known as Pakistani Balochistan had become part of the Harappan cultural orbit,[16] providing key resources to the expansive settlements of the Indus river basin to the east.

From the 1st century to the 3rd century CE, the region was ruled by the Pāratarājas (lit. "Pārata Kings"), a dynasty of Indo-Scythian or Indo-Parthian kings. The dynasty of the Pāratas is thought to be identical with the Pāradas of the Mahabharata, the Puranas and other Vedic and Iranian sources.[17] The Parata kings are primarily known through their coins, which typically exhibit the bust of the ruler (with long hair in a headband) on the obverse, and a swastika within a circular legend on the reverse, written in Brahmi (usually silver coins) or Kharoshthi (copper coins). These coins are mainly found in Loralai in today's western Pakistan.

Herodotus in 450 BCE described the Paraitakenoi as a tribe ruled by Deiokes, a Persian king, in northwestern Persia (History I.101). Arrian describes how Alexander the Great encountered the Pareitakai in Bactria and Sogdiana, and had them conquered by Craterus (Anabasis Alexandrou IV). The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (1st century CE) describes the territory of the Paradon beyond the Ommanitic region, on the coast of modern Balochistan.[18]

The region was fully Islamized by the 9th century and became part of the territory of the Saffarids of Zaranj, followed by the Ghaznavids, then the Ghorids. Ahmad Shah Durrani made it part of the Afghan Empire in 1749. In 1758 the Khan of Kalat, Mir Noori Naseer Khan Baloch, revolted against Ahmed Shah Durrani, defeated him, and freed Balochistan, winning complete independence.[19][20][21][22]

Governance and political disputes

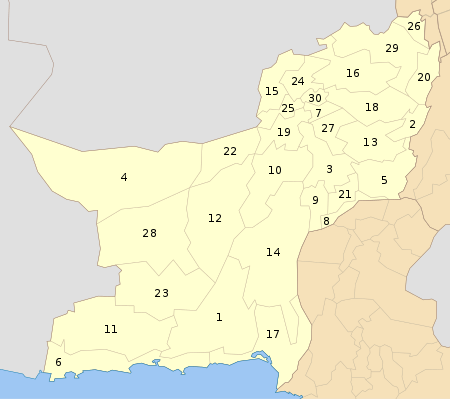

The Balochistan region is administratively divided among three countries, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iran. The largest portion in area and population is in Pakistan, whose largest province (in land area) is Balochistan. An estimated 6.9 million of Pakistan's population is Baloch. In Iran there are about two million ethnic Baloch[23] and a majority of the population of the eastern Sistan and Baluchestan Province is of Baloch ethnicity. The Afghan portion of Balochistan includes the Chahar Burjak District of Nimruz Province, and the Registan Desert in southern Helmand and Kandahar provinces. The governors of Nimruz province in Afghanistan belong to the Baloch ethnic group.

In Pakistan, insurgencies by Baloch nationalists in Balochistan province have been fought in 1948, 1958–59, 1962–63 and 1973–77 — with a new ongoing and reportedly stronger, broader insurgency beginning in 2003.[24] Historically, "drivers" of the conflict are reported to include "tribal divisions", the Baloch-Pashtun ethnic divisions, "marginalization by Punjabi interests", and "economic oppression".[25] In Iran, separatist fighting has reportedly not gained as much ground as the conflict in Pakistan,[26] but has grown and become more sectarian since 2012,[23] with the majority-Sunni Baloch showing a greater degree of Salafist and anti-Shia ideology in their fight against the Shia-Islamist Iranian government.[23]

Arts and Culture

Arts

Many Baluchi are self-sufficient, and they rely on their own skills to construct their houses and many of the tools necessary in their day-to-day life. Rugs are woven for household use and as items of trade also.

Although the Baluchi are largely an illiterate people and their language was until quite recently unwritten, they have a long tradition of poetic composition, and poets and professional minstrels have been held in high esteem. Their oral literature consists of epic poetry, ballads of war and Romance, religious compositions, and folktales. Much composition is given over to genealogical recitals as well. This poetic creativity traditionally had a practical as well as aesthetic aspect—professional minstrels long held the responsibility of carrying information from one to another of the scattered Baluchi settlements, and during the time of the First Baluchi Confederacy these traveling singers provided an important means by which the individual leaders of each tribe within the confederacy could be linked to the central leadership. The earliest securely dated Baluchi poem still known today dates to the late twelfth century, although the tradition of such compositions is no doubt of much greater antiquity.[27]

Literature

The literature of Baluchi—until quite recently entirely oral and still largely so—consists of a large amount of history and occasional balladry (epic poetry), stories and legends, romantic ballads, and religious and didactic poetry, of which there is an extensive corpus; in addition there is a large variety of domestic verse: work songs, lullabies, and riddles. Possibly the first modest attempt to collect some of this extensive literature is represented by the manuscript BM Cod. Add. 24048 (Elfenbein, 1982). In any case it is quite certain that no systematic attempts were made to collect and reduce to written form any sizeable part of this literature prior to the European (mainly British) interest in it in the 19th century. Of these collections, the earliest of note was made by A. Lewis in 1855; the next important one was by T. J. L. Mayer in 1900. By far the most important and systematic, however, are those by M. Longworth Dames, in 1891, 1907, and 1909. Unfortunately all of these works deal with material which came only from one small area, and in Eastern Hill Baluchi only, thus giving a misleadingly restricted picture of the real extent and variety of this literature, and an inflated estimate of the importance of the dialect in which it was collected. The language of classical Baluchi poetry is traditionally in three dialects (in order of their status and importance): Coastal, Eastern Hill Baluchi, and Kechi.[28]

See also

References

- ↑ Iran, Library of Congress, Country Profile . Retrieved December 5, 2009.

- ↑ Afghanistan, CIA World Factbook . Retrieved December 5, 2009.

- ↑ Central Intelligence Agency (2013). "The World Factbook: Ethnic Groups". Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ↑ Other variations of the spelling, especially on French maps, include: Beloutchistan, Baloutchistan.

- 1 2 Pillalamarri, Akhilesh (12 February 2016). "A Brief History of Balochistan". thediplomat.com. THE DIPLOMAT. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ↑ "Human Rights in Balochistan: A Case Study in Failure and Invisibility". THE HUFFINGTON POST. 25 March 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ↑ Elfenbein, J. (1988), "Baluchistan iii. Baluchi Language and Literature", Encyclopaedia Iranica

- ↑ Parpola 2015, Ch. 17: "The identification of Meluhha with the Greater Indus Valley is now almost universally accepted."

- ↑ Hansman 1973, p. 564.

- ↑ Hansman 1973, p. 565.

- ↑ Hansman 1973, pp. 568–569.

- ↑ Parpola & Parpola 1975, pp. 217–220.

- ↑ Thapar 1975, p. 10.

- ↑ Bevan, Edwyn Robert (12 November 2015), The House of Seleucus, Cambridge University Press, p. 272, ISBN 978-1-108-08275-4

- ↑ Hansman 1973

- ↑ Doshi, Riddhi (17 May 2015). "What did Harappans eat, how did they look? Haryana has the answers". Hindustan Times. HT Media.

- ↑ Tandon 2006, p. 183.

- ↑ Tandon 2006, pp. 201–202.

- ↑ "Ahmad Shah and the Durrani Empire". Library of Congress Country Studies on Afghanistan. 1997. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ↑ Friedrich Engels (1857). "Afghanistan". Andy Blunden. The New American Cyclopaedia, Vol. I. Archived from the original on 18 October 2010. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

Afghanistan ... an extensive country of Asia...between Persia and the Indies, and in the other direction between the Hindu Kush and the Indian Ocean. It formerly included the Persian provinces of Khorassan and Kohistan, together with Herat, Beluchistan, Cashmere, and Sinde, and a considerable part of the Punjab... Its principal cities are Kabul, the capital, Ghuznee, Peshawer, and Kandahar

- ↑ "Aḥmad Shah Durrānī". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2010. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ↑ Clements, Frank (2003). Conflict in Afghanistan: a historical encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-85109-402-8. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- 1 2 3 Grassi, Daniele (20 October 2014). "Iran's Baloch insurgency and the IS". Asia Times Online. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ↑ Hussain, Zahid (Apr 25, 2013). "The battle for Balochistan". Dawn. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- ↑ Kupecz, Mickey (Spring 2012). "PAKISTAN'S BALOCH INSURGENCY: History, Conflict Drivers, and Regional Implications" (PDF). International Affairs Review. 20 (3): 106. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ↑ Bhargava, G. S. "How Serious Is the Baluch Insurgency?," Asian Tribune (Apr. 12, 2007) available at http://www.asiantribune.com/node/5285 (accessed Dec. 2, 2011)

- ↑ http://www.encyclopedia.com/places/asia/pakistan-and-bangladesh-political-geography/baluchi

- ↑ http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/baluchistan-iii

Bibliography

- Dashti, Naseer (2012), The Baloch and Balochistan: A Historical Account from the Beginning to the Fall of the Baloch State, Trafford Publishing, pp. 33–, ISBN 978-1-4669-5896-8

- Hansman, John (1973), "A Periplus of Magan and Meluhha", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 36 (3): 553–587, doi:10.1017/S0041977X00119858, JSTOR 613582

- Hansman, John (1975), "A further note on Magan and Meluhha (Notes and Communications)", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 38 (3): 609–610, doi:10.1017/s0041977x00048126, JSTOR 613711

- Parpola, Asko; Parpola, Simo (1975), "On the relationship of the Sumerian toponym Meluhha and Sanskrit mleccha", Studia Orientalia, 46: 205–238

- Parpola, Asko (2015), The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-022692-3

- Tandon, Pankaj (2006), "New light on the Pāratarājas" (PDF), Numismatic Chronicle, 166, JSTOR 42666407

- Thapar, Romila (January 1975), "A Possible Identification of Meluḫḫa, Dilmun and Makan", Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 18 (1): 1–42, doi:10.1163/156852075x00010, JSTOR 3632219

External links

- Persia (Iran), Afghanistan and Baluchistan is a map from 1897 published by The Century Company

- Afghanistan, Beloochistan, etc. is a map from 1893 published by the American Methodist Church

- Balochistan Archives- Preserving our Past