Afrin, Syria

| Afrin عفرين Efrîn | |

|---|---|

View of Afrin (2009 photograph) | |

Afrin | |

| Coordinates: 36°30′30″N 36°52′9″E / 36.50833°N 36.86917°ECoordinates: 36°30′30″N 36°52′9″E / 36.50833°N 36.86917°E | |

| Country |

|

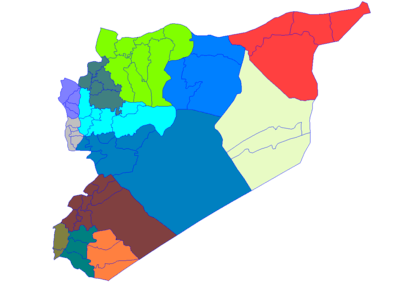

| Governorate | Aleppo |

| District | Afrin |

| Subdistrict | Afrin |

| Control |

|

| Elevation | 270 m (890 ft) |

| Population (2004 census)[1] | |

| • Total | 36,562 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

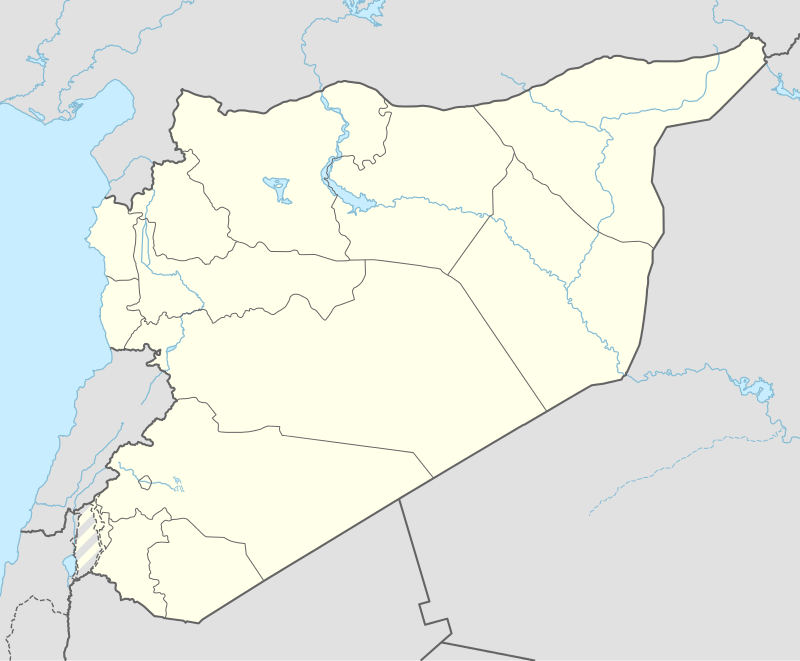

Afrin (Arabic: عفرين, translit. ʿAfrīn or ʿIfrīn; Kurdish: Efrîn or Afrîn; Classical Syriac: ܥܦܪܝܢ) is a district as well as a city in northern Syria. As a district (mantiqah) of Syria, it is part of the Aleppo Governorate. The total population of the district as of 2005 was recorded at 172,095 people, of whom 36,562 lived in the town of Afrin itself.

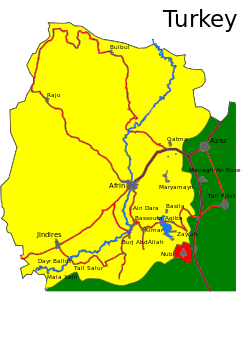

The town and district are named for the Afrin River. The town of Afrin is located next to a bridge of the Aleppo road. The city is split into two distinct halves by the river. As a result of the Turkish military operation in Afrin, the Kurdish-led People's Protection Units (YPG) and Women's Protection Units (YPJ) withdrew from Afrin and the town was encircled by the Turkish-backed Free Syrian Army and the Turkish Armed Forces on 17 March 2018. TAF and TFSA forces captured Afrin on 18 March 2018.[2] An estimated 50,000 to 70,000 people have remained in Afrin city after the Turkish capture.[3]

History

and kings (?) [...]ed me up with ... .

[...] raise[d] up the hand to tar-

hunzas,

and [...

Translation of the surviving inscription from the Afrin Stele.[4]

About 8 km south of the town of Afrin, there are the remains of a Neo-Hittite (Iron Age) settlement known as Tell Ain Dara. In a field northwest of the city, a 9th or 8th century BC Luwian stele (named the Afrin stele) was discovered; it is a fragment of a full stele as only the middle section survives, which in turn is damaged with the right side totally destroyed taking with it parts of the right edge of the front and left edge of the back.[5] The stele's front shows a part of a relief; a short fringed kilt usually worn by the Hittite storm god is shown indicating that the stele was a storm god one.[5]

Cyrrhus overlooking the Afrin River once served as a military base for the Romans conducting campaigns against the Armenian Empire to the north. By the 4th Century it had become an important centre for Christianity with its own bishop. [6]

The Afrin valley was part of Roman Syria until the Muslim conquest of the Levant in 637.[7] The Afrin river was known as Oinoparas in the Seleucid era, in the Roman era the name became Ufrenus, whence the Arab vernacular ʿAfrīn, ʿIfrīn, adopted as Kurdish Efrîn.

The area was briefly conquered by the Principality of Antioch, but again came under Muslim rule in 1260 following the Mongol invasions. In the Ottoman period, the area was part of the Kilis Province.

Although it is not contiguous with the main area of Kurdish settlement, the Afrin valley seems to have seen Kurdish settlement by at least the 18th century, as by that time it is referred to as the Sancak of the Kurds in Ottoman documents.[8]

Modern era

With the drawing of the Syria–Turkey border in 1923, Afrin became detached from Kilis Province and was part of French-administrated Syria (i.e. the State of Aleppo, State of Syria (1924–30), Syrian Republic (1930–58)) and was eventually incorporated in modern Syria at the state's formation in 1961.

The town of Afrin was founded as a market in the 19th century. In 1929, the number of permanent residents was 800, growing to 7,000 by 1968. The town was developed by France under the French mandate of Syria. The main square is Afrin bus station, and the old settlement area stretches northward on the slope of a hill, but more recently habitations have spread to the other side of the river and extend as far to the south-east as the neighboring village of Turandah.

Since the Turkish annexation of Hatay Province in 1939, the Afrin District is now almost surrounded by the Syria–Turkey border, apart from the border with the Azaz District to the east and a short border with the Mount Simeon District to the southeast.

There was an outbreak of civil unrest on 21 March 1986, during which three people were killed by Syrian police. In 1999, the arrest of Kurdish leader Abdullah Öcalan triggered renewed clashes between Kurdish protesters and the police.

Syrian Civil War

During the Syrian Civil War, Syrian government forces withdrew from the city during the summer of 2012. The Popular Protection Units (commonly known as YPG) took control of the city soon afterward.[9][10][11]

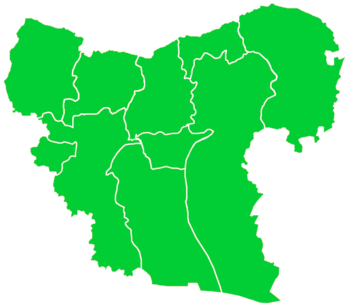

Afrin Canton as a de facto autonomous part was declared on 29 January 2014,[12][13] The administrative center of Afrîn Canton is the town of Afrîn.[14] The Prime minister of Afrin Canton is Hevi Ibrahim. The local government feels threatened by Nusra Front in the Syrian Civil War.[15] According to the Constitution of Rojava, the Afrîn Canton's Legislative Assembly on its 29 January 2014 session declared autonomy. The assembly elected Hêvî Îbrahîm Mustefa prime minister, who appointed Remzi Şêxmus and Ebdil Hemid Mistefa her deputies.[16]

On 20 January 2018, Turkish Air Force bombed more than 100 targets in Afrin.[17] On 28 January 2018 Syria’s antiquities department and the British-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, said that Turkish shelling had seriously damaged the ancient temple of Ain Dara at Afrin. Syria called for international pressure on Turkey “to prevent the targeting of archaeological and cultural sites”.[18][19] On 20 February 2018, the Syrian army convoy consisting of 50 vehicles had arrived in the Afrin through the Ziyarat border crossing and were deployed to different areas. Five vehicles reached the center of the city of Afrin.[20].

On 18 March 2018, on the 58th day of the Turkish military operation in Afrin, the Turkish-backed Free Syrian Army and the Turkish Armed Forces captured Afrin from the YPG and the YPJ, with YPG/J putting up little resistance.[2] Shortly after its capture, TFSA fighters looted parts of the city and destroyed numerous Kurdish symbols, including a statue of Kāve, as Turkish Army troops solidified control by raising Turkish flags and banners over the city.[21]

On 26 March 2018, Turkish state media outlet Anadolu Agency published video showing children in Afrin attending a school with a large photo of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan near the front door.[22] The video additionally shows children in Afrin waving Turkish flags and teachers instructing the students to chant pro-Erdogan slogans.

On 12 April 2018, a Turkish-backed interim council was elected in Afrin, consisting of 20 “elders from the city” – 11 Kurds, eight Arabs, and one Turkmen, Turkish state media reported.[23] The council is headed by a Kurd named Zuhair Haider who, in an interview with the state-run Anadolu Agency, expressed his gratitude to Turkey and vowed to “serve” the local citizens.[24]

Education

In August 2015, the University of Afrin started teaching, with initial programs in literature, engineering and economics, including institutes for medicine, topographic engineering, music and theater, business administration and the Kurdish language.[25]

Economy

The olive tree is the symbol of Afrin. Afrin is a major production center for olives. Olive oil pressing and textiles are some of the city's local industries.

Climate

Afrin has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate with influences of a continental climate during winter with hot dry summers and cool wet and occasionally snowy winters. The average high temperature in January is 9 °C and the average high temperature in July is 34 °C. The snow falls usually in January, February or December. Afrin is characterized by abundant rain in winter months. The yearly rainfall ranges between 500 and 600 mm and the average rate of humidity is 61%. Afrin has a moderate climate and is surrounded by olive trees.

| Climate data for Afrin | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18 (64) |

22 (72) |

26 (79) |

35 (95) |

41 (106) |

41 (106) |

43 (109) |

46 (115) |

42 (108) |

38 (100) |

28 (82) |

21 (70) |

46 (115) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 9 (48) |

12 (54) |

16 (61) |

22 (72) |

26 (79) |

29 (84) |

34 (93) |

34 (93) |

28 (82) |

25 (77) |

17 (63) |

11 (52) |

22 (72) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6 (43) |

8 (46) |

11 (52) |

16 (61) |

20 (68) |

24 (75) |

28 (82) |

28 (82) |

23 (73) |

20 (68) |

13 (55) |

8 (46) |

17 (63) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2 (36) |

4 (39) |

7 (45) |

11 (52) |

15 (59) |

19 (66) |

22 (72) |

22 (72) |

18 (64) |

15 (59) |

8 (46) |

4 (39) |

12 (54) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −11 (12) |

−7 (19) |

−7 (19) |

0 (32) |

6 (43) |

10 (50) |

14 (57) |

11 (52) |

6 (43) |

2 (36) |

−3 (27) |

−6 (21) |

−11 (12) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 110 (4.33) |

85 (3.35) |

60 (2.36) |

40 (1.57) |

30 (1.18) |

10 (0.39) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

15 (0.59) |

50 (1.97) |

70 (2.76) |

95 (3.74) |

565 (22.24) |

| Average rainy days | 16 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 15 | 88 |

| Average snowy days | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 84 | 76 | 69 | 65 | 51 | 49 | 41 | 44 | 52 | 56 | 67 | 83 | 61 |

| Source: Weather Online, Weather Base, BBC Weather, MyForecast and My Weather 2 | |||||||||||||

Notable people

- Ebdo Mihemed, singer

See also

- Yazidis in Syria

- Turkish military operation in Afrin

- Yazidis in Afrin Region

References

- ↑ General Census of Population and Housing 2004. Syria Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). Aleppo Governorate. (in Arabic)

- 1 2 "Syria war: Turkey-backed forces oust Kurds from heart of Afrin". BBC. 18 March 2018.

- ↑ "Turkish-backed interim council elected in Afrin: state media".

- ↑ John David Hawkins (2000). Inscriptions of the Iron Age: Part 1: Text, Introduction, Karatepe, Karkamis, Tell Ahmar, Maras, Malatya, Commagene. Part 2: Text, Amuq, Aleppo, Hama, Tabal, Assur Letters, Miscellaneous, Seals, Indices. Part 3: Plates. p. 387.

- 1 2 John David Hawkins (2000). Inscriptions of the Iron Age: Part 1: Text, Introduction, Karatepe, Karkamis, Tell Ahmar, Maras, Malatya, Commagene. Part 2: Text, Amuq, Aleppo, Hama, Tabal, Assur Letters, Miscellaneous, Seals, Indices. Part 3: Plates. p. 386.

- ↑ Darke, Diana (2018). "How historical Afrin became a prize worth a war". BBC News. Retrieved 2018-01-26.

- ↑ Andrew Palmer, The Seventh Century in the West-Syrian Chronicles (1993), p. 209, fn. 525.

- ↑ Winter, Stefan (2005). "Les Kurdes du Nord-Ouest syrien et l'État ottoman, 1690-1750". In Afifi, Mohammad. Sociétés rurales ottomanes. Cairo: IFAO. pp. 243–258. ISBN 2724704118.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 July 2012. Retrieved 2012-07-27.

- ↑ "Liberated Kurdish Cities in Syria Move into Next Phase". Rudaw. 25 July 2012. Archived from the original on 28 July 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ "Kurdish muscle flexing". Jerusalem Post. 14 November 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ↑ "Democratic autonomy has declared in Afrin canton in Rojava". Mednuce. 29 January 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ↑ "After Cizîre, Kobanê Canton has been declared". Firat News. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ↑ "The Constitution of the Rojava Cantons; Personal Website of Mutlu Civiroglu". civiroglu.net. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ↑ "Syria's Kurds Warn Afrin Could Be The New Kobani".

- ↑ ÇİFTE DEVRİM in Özgür Gündem

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/20/world/middleeast/turkey-bombs-kurds-syria.html?smid=fb-nytimes&smtyp=cur

- ↑ "Ancient Syrian temple damaged in Turkish raids against Kurds". timesofisrael. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ↑ "Syrian government says Turkish shelling damaged ancient temple". reuters. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ↑ "Pro-Syrian government forces reach central Afrin despite Turkish shelling". Kurdistan 24. 20 February 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ↑ "Pro-Turkish forces pillage Afrin after taking Syrian city". Yahoo news. 18 March 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- ↑ "Children return to school in Afrin after 2 years". Anadolu Agency. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ↑ "Interim local council established in Syria's Afrin". 12 April 2018.

- ↑ "Turkish-backed interim council elected in Afrin: state media".

- ↑ "Syria's first Kurdish university attracts controversy as well as students". Al-Monitor. 18 May 2016. Archived from the original on 21 May 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Afrin. |