Ethanol

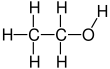

Ethanol (also called ethyl alcohol, grain alcohol, drinking alcohol, or simply alcohol) is a chemical compound, a simple alcohol with the chemical formula C

2H

6O. Its formula can be also written as CH

3−CH

2−OH or C

2H

5OH (an ethyl group linked to a hydroxyl group), and is often abbreviated as EtOH. Ethanol is a volatile, flammable, colorless liquid with a slight characteristic odor. It is a psychoactive substance and is the principal active ingredient found in alcoholic drinks.

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈɛθənɒl/ | ||

| Preferred IUPAC name

Ethanol[1] | |||

| Other names

Absolute alcohol alcohol cologne spirit drinking alcohol ethylic alcohol EtOH ethyl alcohol ethyl hydrate ethyl hydroxide ethylol grain alcohol hydroxyethane methylcarbinol | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| 3DMet | |||

| 1718733 | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.526 | ||

| E number | E1510 (additional chemicals) | ||

| 787 | |||

PubChem CID |

|||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | UN 1170 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C2H6O | |||

| Molar mass | 46.069 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colorless liquid | ||

| Density | 0.7893 g/cm3 (at 20 °C)[2] | ||

| Melting point | −114.14 ± 0.03[2] °C (−173.45 ± 0.05 °F; 159.01 ± 0.03 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 78.24 ± 0.09[2] °C (172.83 ± 0.16 °F; 351.39 ± 0.09 K) | ||

| miscible | |||

| log P | −0.18 | ||

| Vapor pressure | 5.95 kPa (at 20 °C) | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | 15.9 (H2O), 29.8 (DMSO)[3][4] | ||

| −33.60·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

Refractive index (nD) |

1.3611[2] | ||

| Viscosity | 1.2 mPa·s (at 20 °C), 1.074 mPa·s (at 25 °C)[5] | ||

| 1.69 D[6] | |||

| Hazards | |||

| Safety data sheet | See: data page [7] | ||

| GHS pictograms |   | ||

| GHS Signal word | Danger | ||

GHS hazard statements |

H225, H319 | ||

| P210, P280, P305+351+338 | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | 14 °C (Absolute) | ||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LD50 (median dose) |

7340 mg/kg (oral, rat) 7300 mg/kg (mouse) | ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 1000 ppm (1900 mg/m3) [8] | ||

REL (Recommended) |

TWA 1000 ppm (1900 mg/m3) [8] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

N.D.[8] | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related compounds |

Ethane Methanol | ||

| Supplementary data page | |||

| Refractive index (n), Dielectric constant (εr), etc. | |||

Thermodynamic data |

Phase behaviour solid–liquid–gas | ||

| UV, IR, NMR, MS | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| Infobox references | |||

Ethanol is naturally produced by the fermentation of sugars by yeasts or via petrochemical processes, and is commonly consumed as a popular recreational drug. It also has medical applications as an antiseptic and disinfectant. The compound is widely used as a chemical solvent, either for scientific chemical testing or in synthesis of other organic compounds, and is a vital substance used across many different kinds of manufacturing industries. Ethanol is also used as an alternative fuel source.

Etymology

Ethanol is the systematic name defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) for a compound consisting of alkyl group with two carbon atoms (prefix “eth-”), having a single bond between them (infix “-an-”), attached functional group −OH group (suffix “-ol”).[9]

The “eth-” prefix and the qualifier “ethyl” in “ethyl alcohol” originally come from the name “ethyl” assigned in 1834 to the group C

2H

5− by Justus Liebig. He coined the word from the German name Aether of the compound C

2H

5−O−C

2H

5 (commonly called “ether” in English, more specifically called “diethyl ether”).[10] According to the Oxford English Dictionary, Ethyl is a contraction of the Ancient Greek αἰθήρ (aithḗr, “upper air”) and the Greek word ὕλη (hýlē, “substance”).[11]

The name ethanol was coined as a result of a resolution that was adopted at the International Conference on Chemical Nomenclature that was held in April 1892 in Geneva, Switzerland.[12]

The term “alcohol” now refers to a wider class of substances in chemistry nomenclature, but in common parlance it remains the name of ethanol. The Oxford English Dictionary claims that it is a medieval loan from Arabic al-kuḥl, a powdered ore of antimony used since antiquity as a cosmetic, and retained that meaning in Middle Latin.[13] The use of “alcohol” for ethanol (in full, “alcohol of wine”) is modern, first recorded 1753, and by the later 18th century referred to “any sublimated substance”; “distilled spirit” used for “the spirit of wine” (shortened from a full expression the spirit of alcohol of wine). The systematic use in chemistry dates to 1850.

Uses

Medical

Antiseptic

Ethanol is used in medical wipes and most commonly in antibacterial hand sanitizer gels as an antiseptic for its bactericidal and anti-fungal effects.[14] Ethanol kills microorganisms by dissolving their membrane lipid bilayer and denaturing their proteins, and is effective against most bacteria and fungi and viruses. However, it is ineffective against bacterial spores, but that can be alleviated by using hydrogen peroxide.[15] A solution of 70% ethanol is more effective than pure ethanol because ethanol relies on water molecules for optimal antimicrobial activity. Absolute ethanol may inactivate microbes without destroying them because the alcohol is unable to fully permeate the microbe's membrane.[16][17] Ethanol can also be used as a disinfectant and antiseptic because it causes cell dehydration by disrupting the osmotic balance across cell membrane, so water leaves the cell leading to cell death.[18]

Antidote

Ethanol may be administered as an antidote to methanol,[19] isopropyl alcohol and ethylene glycol poisoning.[20]

Medicinal solvent

Ethanol, often in high concentrations, is used to dissolve many water-insoluble medications and related compounds. Liquid preparations of pain medications, cough and cold medicines, and mouth washes, for example, may contain up to 25% ethanol[21] and may need to be avoided in individuals with adverse reactions to ethanol such as alcohol-induced respiratory reactions.[22] Ethanol is present mainly as an antimicrobial preservative in over 700 liquid preparations of medicine including acetaminophen, iron supplements, ranitidine, furosemide, mannitol, phenobarbital, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and over-the-counter cough medicine.[23]

Pharmacology

If ingested orally, ethanol is extensively metabolized by the liver, particularly via the enzyme CYP450.[24] Ethyl alcohol increases the secretion of acids in the stomach.[24] The metabolite acetaldehyde is responsible for much of the short term, and long term effects of ethyl alcohol toxicity.[25]

Recreational

As a central nervous system depressant, ethanol is one of the most commonly consumed psychoactive drugs.[26]

Fuel

Engine fuel

| Fuel type | MJ/L | MJ/kg | Research octane number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dry wood (20% moisture) | ~19.5 | ||

| Methanol | 17.9 | 19.9 | 108.7[28] |

| Ethanol | 21.2[29] | 26.8[29] | 108.6[28] |

| E85 (85% ethanol, 15% gasoline) | 25.2 | 33.2 | 105 |

| Liquefied natural gas | 25.3 | ~55 | |

| Autogas (LPG) (60% propane + 40% butane) | 26.8 | 50 | |

| Aviation gasoline (high-octane gasoline, not jet fuel) | 33.5 | 46.8 | 100/130 (lean/rich) |

| Gasohol (90% gasoline + 10% ethanol) | 33.7 | 47.1 | 93/94 |

| Regular gasoline/petrol | 34.8 | 44.4[30] | min. 91 |

| Premium gasoline/petrol | max. 104 | ||

| Diesel | 38.6 | 45.4 | 25 |

| Charcoal, extruded | 50 | 23 |

The largest single use of ethanol is as an engine fuel and fuel additive. Brazil in particular relies heavily upon the use of ethanol as an engine fuel, due in part to its role as one of the globe's leading producers of ethanol.[31] Gasoline sold in Brazil contains at least 25% anhydrous ethanol. Hydrous ethanol (about 95% ethanol and 5% water) can be used as fuel in more than 90% of new gasoline fueled cars sold in the country. Brazilian ethanol is produced from sugar cane and noted for high carbon sequestration.[32] The US and many other countries primarily use E10 (10% ethanol, sometimes known as gasohol) and E85 (85% ethanol) ethanol/gasoline mixtures.

Ethanol has been used as rocket fuel and is currently in lightweight rocket-powered racing aircraft.[33]

Australian law limits the use of pure ethanol from sugarcane waste to 10% in automobiles. Older cars (and vintage cars designed to use a slower burning fuel) should have the engine valves upgraded or replaced.[34]

According to an industry advocacy group, ethanol as a fuel reduces harmful tailpipe emissions of carbon monoxide, particulate matter, oxides of nitrogen, and other ozone-forming pollutants.[35] Argonne National Laboratory analyzed greenhouse gas emissions of many different engine and fuel combinations, and found that biodiesel/petrodiesel blend (B20) showed a reduction of 8%, conventional E85 ethanol blend a reduction of 17% and cellulosic ethanol 64%, compared with pure gasoline.[36]

Ethanol combustion in an internal combustion engine yields many of the products of incomplete combustion produced by gasoline and significantly larger amounts of formaldehyde and related species such as acetaldehyde.[37] This leads to a significantly larger photochemical reactivity and more ground level ozone.[38] These data have been assembled into The Clean Fuels Report comparison of fuel emissions[39] and show that ethanol exhaust generates 2.14 times as much ozone as gasoline exhaust.[40] When this is added into the custom Localised Pollution Index (LPI) of The Clean Fuels Report, the local pollution of ethanol (pollution that contributes to smog) is rated 1.7, where gasoline is 1.0 and higher numbers signify greater pollution.[41] The California Air Resources Board formalized this issue in 2008 by recognizing control standards for formaldehydes as an emissions control group, much like the conventional NOx and Reactive Organic Gases (ROGs).[42]

World production of ethanol in 2006 was 51 gigalitres (1.3×1010 US gal), with 69% of the world supply coming from Brazil and the United States.[43] More than 20% of Brazilian cars are able to use 100% ethanol as fuel, which includes ethanol-only engines and flex-fuel engines.[44] Flex-fuel engines in Brazil are able to work with all ethanol, all gasoline or any mixture of both. In the US flex-fuel vehicles can run on 0% to 85% ethanol (15% gasoline) since higher ethanol blends are not yet allowed or efficient. Brazil supports this fleet of ethanol-burning automobiles with large national infrastructure that produces ethanol from domestically grown sugar cane. Sugar cane not only has a greater concentration of sucrose than corn (by about 30%), but is also much easier to extract. The bagasse generated by the process is not wasted, but is used in power plants to produce electricity.

In the United States, the ethanol fuel industry is based largely on corn. According to the Renewable Fuels Association, as of 30 October 2007, 131 grain ethanol bio-refineries in the United States have the capacity to produce 7.0 billion US gallons (26,000,000 m3) of ethanol per year. An additional 72 construction projects underway (in the U.S.) can add 6.4 billion US gallons (24,000,000 m3) of new capacity in the next 18 months. Over time, it is believed that a material portion of the ≈150-billion-US-gallon (570,000,000 m3) per year market for gasoline will begin to be replaced with fuel ethanol.[45]

Sweet sorghum is another potential source of ethanol, and is suitable for growing in dryland conditions. The International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) is investigating the possibility of growing sorghum as a source of fuel, food, and animal feed in arid parts of Asia and Africa.[46] Sweet sorghum has one-third the water requirement of sugarcane over the same time period. It also requires about 22% less water than corn (also known as maize). The world's first sweet sorghum ethanol distillery began commercial production in 2007 in Andhra Pradesh, India.[47]

Ethanol's high miscibility with water makes it unsuitable for shipping through modern pipelines like liquid hydrocarbons.[48] Mechanics have seen increased cases of damage to small engines (in particular, the carburetor) and attribute the damage to the increased water retention by ethanol in fuel.[49]

Rocket fuel

Ethanol was commonly used as fuel in early bipropellant rocket (liquid propelled) vehicles, in conjunction with an oxidizer such as liquid oxygen. The German A-4 ballistic rocket, better known by its propaganda name V-2 rocket of World War II,[50] credited with beginning the space age, used ethanol as the main constituent of B-Stoff, under such nomenclature the ethanol was mixed with 25% of water to reduce the combustion chamber temperature.[51][52] The V-2's design team helped develop U.S. rockets following World War II, including the ethanol-fueled Redstone rocket which launched the first U.S. satellite.[53] Alcohols fell into general disuse as more energy-dense rocket fuels were developed.[52]

Fuel cells

Commercial fuel cells operate on reformed natural gas, hydrogen or methanol. Ethanol is an attractive alternative due to its wide availability, low cost, high purity and low toxicity. There are a wide range of fuel cell concepts that have been trialled including direct-ethanol fuel cells, auto-thermal reforming systems and thermally integrated systems. The majority of work is being conducted at a research level although there are a number of organizations at the beginning of commercialization of ethanol fuel cells.[54]

Household heating

Ethanol fireplaces can be used for home heating or for decoration.[55]

Feedstock

Ethanol is an important industrial ingredient. It has widespread use as a precursor for other organic compounds such as ethyl halides, ethyl esters, diethyl ether, acetic acid, and ethyl amines.

Solvent

Ethanol is considered a universal solvent, as its molecular structure allows for the dissolving of both polar, hydrophilic and nonpolar, hydrophobic compounds. As ethanol also has a low boiling point, it is easy to remove from a solution that has been used to dissolve other compounds, making it a popular extracting agent for botanical oils. Cannabis oil extraction methods often use ethanol as an extraction solvent,[56] and also as a post-processing solvent to remove oils, waxes, and chlorophyll from solution in a process known as winterization.

Ethanol is found in paints, tinctures, markers, and personal care products such as mouthwashes, perfumes and deodorants. However, polysaccharides precipitate from aqueous solution in the presence of alcohol, and ethanol precipitation is used for this reason in the purification of DNA and RNA.

Low-temperature liquid

Because of its low freezing point (−114.14 °C) and low toxicity, ethanol is sometimes used in laboratories (with dry ice or other coolants) as a cooling bath to keep vessels at temperatures below the freezing point of water. For the same reason, it is also used as the active fluid in alcohol thermometers.

Chemistry

Chemical formula

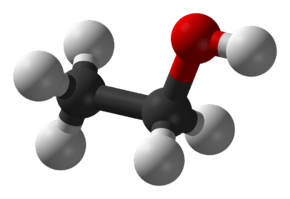

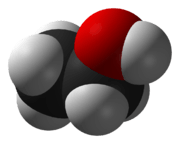

Ethanol is a 2-carbon alcohol. Its molecular formula is CH3CH2OH. An alternative notation is CH3−CH2−OH, which indicates that the carbon of a methyl group (CH3−) is attached to the carbon of a methylene group (−CH2–), which is attached to the oxygen of a hydroxyl group (−OH). It is a constitutional isomer of dimethyl ether. Ethanol is sometimes abbreviated as EtOH, using the common organic chemistry notation of representing the ethyl group (C2H5−) with Et.

Physical properties

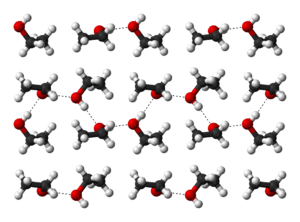

Ethanol is a volatile, colorless liquid that has a slight odor. It burns with a smokeless blue flame that is not always visible in normal light. The physical properties of ethanol stem primarily from the presence of its hydroxyl group and the shortness of its carbon chain. Ethanol's hydroxyl group is able to participate in hydrogen bonding, rendering it more viscous and less volatile than less polar organic compounds of similar molecular weight, such as propane.

Ethanol is slightly more refractive than water, having a refractive index of 1.36242 (at λ=589.3 nm and 18.35 °C or 65.03 °F).[57] The triple point for ethanol is 150 K at a pressure of 4.3 × 10−4 Pa.[58]

Solvent properties

Ethanol is a versatile solvent, miscible with water and with many organic solvents, including acetic acid, acetone, benzene, carbon tetrachloride, chloroform, diethyl ether, ethylene glycol, glycerol, nitromethane, pyridine, and toluene.[57][59] It is also miscible with light aliphatic hydrocarbons, such as pentane and hexane, and with aliphatic chlorides such as trichloroethane and tetrachloroethylene.[59]

Ethanol's miscibility with water contrasts with the immiscibility of longer-chain alcohols (five or more carbon atoms), whose water miscibility decreases sharply as the number of carbons increases.[60] The miscibility of ethanol with alkanes is limited to alkanes up to undecane: mixtures with dodecane and higher alkanes show a miscibility gap below a certain temperature (about 13 °C for dodecane[61]). The miscibility gap tends to get wider with higher alkanes, and the temperature for complete miscibility increases.

Ethanol-water mixtures have less volume than the sum of their individual components at the given fractions. Mixing equal volumes of ethanol and water results in only 1.92 volumes of mixture.[57][62] Mixing ethanol and water is exothermic, with up to 777 J/mol[63] being released at 298 K.

Mixtures of ethanol and water form an azeotrope at about 89 mole-% ethanol and 11 mole-% water[64] or a mixture of 95.6 percent ethanol by mass (or about 97% alcohol by volume) at normal pressure, which boils at 351K (78 °C). This azeotropic composition is strongly temperature- and pressure-dependent and vanishes at temperatures below 303 K.[65]

Hydrogen bonding causes pure ethanol to be hygroscopic to the extent that it readily absorbs water from the air. The polar nature of the hydroxyl group causes ethanol to dissolve many ionic compounds, notably sodium and potassium hydroxides, magnesium chloride, calcium chloride, ammonium chloride, ammonium bromide, and sodium bromide.[59] Sodium and potassium chlorides are slightly soluble in ethanol.[59] Because the ethanol molecule also has a nonpolar end, it will also dissolve nonpolar substances, including most essential oils[66] and numerous flavoring, coloring, and medicinal agents.

The addition of even a few percent of ethanol to water sharply reduces the surface tension of water. This property partially explains the "tears of wine" phenomenon. When wine is swirled in a glass, ethanol evaporates quickly from the thin film of wine on the wall of the glass. As the wine's ethanol content decreases, its surface tension increases and the thin film "beads up" and runs down the glass in channels rather than as a smooth sheet.

Flammability

An ethanol–water solution will catch fire if heated above a temperature called its flash point and an ignition source is then applied to it.[67] For 20% alcohol by mass (about 25% by volume), this will occur at about 25 °C (77 °F). The flash point of pure ethanol is 13 °C (55 °F),[68] but may be influenced very slightly by atmospheric composition such as pressure and humidity. Ethanol mixtures can ignite below average room temperature. Ethanol is considered a flammable liquid (Class 3 Hazardous Material) in concentrations above 2.35% by mass (3.0% by volume; 6 proof).[69][70][71]

Flash points of ethanol–water mixtures[72][70][73] Ethanol

mass fraction, %Temperature °C °F 1 84.5 184.1[70] 2 64 147[70] 2.35 60 140[70][69] 3 51.5 124.7[70] 5 43 109[72] 6 39.5 103.1[70] 10 31 88[72] 20 25 77[70] 30 24 75[72] 40 21.9 71.4[72] 50 20 68[72][70] 60 17.9 64.2[72] 70 16 61[72] 80 15.8 60.4[70] 90 14 57[72] 100 12.5 54.5[72][70][68]

Dishes using burning alcohol for culinary effects are called flambé.

Natural occurrence

Ethanol is a byproduct of the metabolic process of yeast. As such, ethanol will be present in any yeast habitat. Ethanol can commonly be found in overripe fruit.[74] Ethanol produced by symbiotic yeast can be found in bertam palm blossoms. Although some animal species, such as the pentailed treeshrew, exhibit ethanol-seeking behaviors, most show no interest or avoidance of food sources containing ethanol.[75] Ethanol is also produced during the germination of many plants as a result of natural anaerobiosis.[76] Ethanol has been detected in outer space, forming an icy coating around dust grains in interstellar clouds.[77] Minute quantity amounts (average 196 ppb) of endogenous ethanol and acetaldehyde were found in the exhaled breath of healthy volunteers.[78] Auto-brewery syndrome, also known as gut fermentation syndrome, is a rare medical condition in which intoxicating quantities of ethanol are produced through endogenous fermentation within the digestive system.[79]

Production

Ethanol is produced both as a petrochemical, through the hydration of ethylene and, via biological processes, by fermenting sugars with yeast.[80] Which process is more economical depends on prevailing prices of petroleum and grain feed stocks. In the 1970s most industrial ethanol in the United States was made as a petrochemical, but in the 1980s the United States introduced subsidies for corn-based ethanol and today it is almost all made from that source.[81]

Ethylene hydration

Ethanol for use as an industrial feedstock or solvent (sometimes referred to as synthetic ethanol) is made from petrochemical feed stocks, primarily by the acid-catalyzed hydration of ethylene:

- C

2H

4 + H

2O → CH

3CH

2OH

The catalyst is most commonly phosphoric acid,[82][83] adsorbed onto a porous support such as silica gel or diatomaceous earth. This catalyst was first used for large-scale ethanol production by the Shell Oil Company in 1947.[84] The reaction is carried out in the presence of high pressure steam at 300 °C (572 °F) where a 5:3 ethylene to steam ratio is maintained.[85][86] This process was used on an industrial scale by Union Carbide Corporation and others in the U.S., but now only LyondellBasell uses it commercially.

In an older process, first practiced on the industrial scale in 1930 by Union Carbide,[87] but now almost entirely obsolete, ethylene was hydrated indirectly by reacting it with concentrated sulfuric acid to produce ethyl sulfate, which was hydrolyzed to yield ethanol and regenerate the sulfuric acid:[88]

- C

2H

4 + H

2SO

4 → CH

3CH

2SO

4H - CH

3CH

2SO

4H + H

2O → CH

3CH

2OH + H

2SO

4

From CO2

CO2 can also be used as the raw material.

CO2 can be reduced by hydrogen to produce ethanol, acetic acid, and smaller amounts of 2,3-butanediol and lactic acid using Clostridium ljungdahlii, Clostridium autoethanogenum or Moorella sp. HUC22-1.[89][90]

CO2 can be converted using electrochemical reactions at room temperature and pressure.[91][92] In a system developed at Delft University of Technology, a copper nanowire array used as a cathode adsorbs molecules of carbon dioxide and reduced intermediate species such as CO and COH. However, even in the best results about half the current went into producing hydrogen and only a small amount of ethanol was produced. Other products, produced in larger quantities, were (in decreasing order) formic acid, ethylene, CO, and n-propanol.[93]

From lipids

Lipids can also be used to make ethanol and can be found in such raw materials such as algae.[94]

Fermentation

Ethanol in alcoholic beverages and fuel is produced by fermentation. Certain species of yeast (e.g., Saccharomyces cerevisiae) metabolize sugar, producing ethanol and carbon dioxide. The chemical equations below summarize the conversion:

Fermentation is the process of culturing yeast under favorable thermal conditions to produce alcohol. This process is carried out at around 35–40 °C (95–104 °F). Toxicity of ethanol to yeast limits the ethanol concentration obtainable by brewing; higher concentrations, therefore, are obtained by fortification or distillation. The most ethanol-tolerant yeast strains can survive up to approximately 18% ethanol by volume.

To produce ethanol from starchy materials such as cereals, the starch must first be converted into sugars. In brewing beer, this has traditionally been accomplished by allowing the grain to germinate, or malt, which produces the enzyme amylase. When the malted grain is mashed, the amylase converts the remaining starches into sugars.

Cellulose

Sugars for ethanol fermentation can be obtained from cellulose. Deployment of this technology could turn a number of cellulose-containing agricultural by-products, such as corncobs, straw, and sawdust, into renewable energy resources. Other agricultural residues such as sugar cane bagasse and energy crops such as switchgrass may also be fermentable sugar sources.[95]

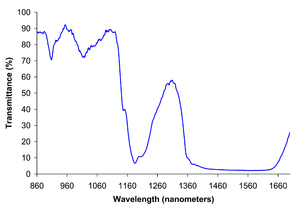

Testing

Breweries and biofuel plants employ two methods for measuring ethanol concentration. Infrared ethanol sensors measure the vibrational frequency of dissolved ethanol using the C−H band at 2900 cm−1. This method uses a relatively inexpensive solid-state sensor that compares the C−H band with a reference band to calculate the ethanol content. The calculation makes use of the Beer–Lambert law. Alternatively, by measuring the density of the starting material and the density of the product, using a hydrometer, the change in specific gravity during fermentation indicates the alcohol content. This inexpensive and indirect method has a long history in the beer brewing industry.

Purification

Distillation

Ethylene hydration or brewing produces an ethanol–water mixture. For most industrial and fuel uses, the ethanol must be purified. Fractional distillation at atmospheric pressure can concentrate ethanol to 95.6% by weight (89.5 mole%). This mixture is an azeotrope with a boiling point of 78.1 °C (172.6 °F), and cannot be further purified by distillation. Addition of an entraining agent, such as benzene, cyclohexane, or heptane, allows a new ternary azeotrope comprising the ethanol, water, and the entraining agent to be formed. This lower-boiling ternary azeotrope is removed preferentially, leading to water-free ethanol.[83]

At pressures less than atmospheric pressure, the composition of the ethanol-water azeotrope shifts to more ethanol-rich mixtures, and at pressures less than 70 torr (9.333 kPa), there is no azeotrope, and it is possible to distill absolute ethanol from an ethanol-water mixture. While vacuum distillation of ethanol is not presently economical, pressure-swing distillation is a topic of current research. In this technique, a reduced-pressure distillation first yields an ethanol-water mixture of more than 95.6% ethanol. Then, fractional distillation of this mixture at atmospheric pressure distills off the 95.6% azeotrope, leaving anhydrous ethanol at the bottom.

Molecular sieves and desiccants

Apart from distillation, ethanol may be dried by addition of a desiccant, such as molecular sieves, cellulose, and cornmeal. The desiccants can be dried and reused.[83] Molecular sieves can be used to selectively absorb the water from the 95.6% ethanol solution.[96] Synthetic zeolite in pellet form can be used, as well as a variety of plant-derived absorbents, including cornmeal, straw, and sawdust. The zeolite bed can be regenerated essentially an unlimited number of times by drying it with a blast of hot carbon dioxide. Cornmeal and other plant-derived absorbents cannot readily be regenerated, but where ethanol is made from grain, they are often available at low cost. Absolute ethanol produced this way has no residual benzene, and can be used to fortify port and sherry in traditional winery operations.

Membranes and reverse osmosis

Membranes can also be used to separate ethanol and water. Membrane-based separations are not subject to the limitations of the water-ethanol azeotrope because the separations are not based on vapor-liquid equilibria. Membranes are often used in the so-called hybrid membrane distillation process. This process uses a pre-concentration distillation column as first separating step. The further separation is then accomplished with a membrane operated either in vapor permeation or pervaporation mode. Vapor permeation uses a vapor membrane feed and pervaporation uses a liquid membrane feed.

Other techniques

A variety of other techniques have been discussed, including the following:[83]

- Salting using potassium carbonate to exploit its insolubility will cause a phase separation with ethanol and water. This offers a very small potassium carbonate impurity to the alcohol that can be removed by distillation. This method is very useful in purification of ethanol by distillation, as ethanol forms an azeotrope with water.

- Direct electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide to ethanol under ambient conditions using copper nanoparticles on a carbon nanospike film as the catalyst;[97]

- Extraction of ethanol from grain mash by supercritical carbon dioxide;

- Pervaporation;

- Fractional freezing is also used to concentrate fermented alcoholic solutions, such as traditionally made Applejack (beverage);

- Pressure swing adsorption.[98]

Grades of ethanol

Denatured alcohol

Pure ethanol and alcoholic beverages are heavily taxed as psychoactive drugs, but ethanol has many uses that do not involve its consumption. To relieve the tax burden on these uses, most jurisdictions waive the tax when an agent has been added to the ethanol to render it unfit to drink. These include bittering agents such as denatonium benzoate and toxins such as methanol, naphtha, and pyridine. Products of this kind are called denatured alcohol.[99][100]

Absolute alcohol

Absolute or anhydrous alcohol refers to ethanol with a low water content. There are various grades with maximum water contents ranging from 1% to a few parts per million (ppm) levels. If azeotropic distillation is used to remove water, it will contain trace amounts of the material separation agent (e.g. benzene).[101] Absolute alcohol is not intended for human consumption. Absolute ethanol is used as a solvent for laboratory and industrial applications, where water will react with other chemicals, and as fuel alcohol. Spectroscopic ethanol is an absolute ethanol with a low absorbance in ultraviolet and visible light, fit for use as a solvent in ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy.[102]

Pure ethanol is classed as 200 proof in the U.S., equivalent to 175 degrees proof in the UK system.[103]

Rectified spirits

Rectified spirit, an azeotropic composition of 96% ethanol containing 4% water, is used instead of anhydrous ethanol for various purposes. Spirits of wine are about 94% ethanol (188 proof). The impurities are different from those in 95% (190 proof) laboratory ethanol.[104]

Reactions

Ethanol is classified as a primary alcohol, meaning that the carbon that its hydroxyl group attaches to has at least two hydrogen atoms attached to it as well. Many ethanol reactions occur at its hydroxyl group.

Ester formation

In the presence of acid catalysts, ethanol reacts with carboxylic acids to produce ethyl esters and water:

- RCOOH + HOCH2CH3 → RCOOCH2CH3 + H2O

This reaction, which is conducted on large scale industrially, requires the removal of the water from the reaction mixture as it is formed. Esters react in the presence of an acid or base to give back the alcohol and a salt. This reaction is known as saponification because it is used in the preparation of soap. Ethanol can also form esters with inorganic acids. Diethyl sulfate and triethyl phosphate are prepared by treating ethanol with sulfur trioxide and phosphorus pentoxide respectively. Diethyl sulfate is a useful ethylating agent in organic synthesis. Ethyl nitrite, prepared from the reaction of ethanol with sodium nitrite and sulfuric acid, was formerly used as a diuretic.

Dehydration

In the presence of acid catalysts, ethanol converts to ethylene. Typically solid acids such as silica are used:[105]

- CH3CH2OH → H2C=CH2 + H2O

Ethylene produced in this way competes with ethylene from oil refineries and fracking.

Under alternative conditions, diethyl ether results:

- 2 CH3CH2OH → CH3CH2OCH2CH3 + H2O

Combustion

Complete combustion of ethanol forms carbon dioxide and water:

- C2H5OH (l) + 3 O2 (g) → 2 CO2 (g) + 3 H2O (l); −ΔHc = 1371 kJ/mol[106] = 29.8 kJ/g = 327 kcal/mol = 7.1 kcal/g

- C2H5OH (l) + 3 O2 (g) → 2 CO2 (g) + 3 H2O (g); −ΔHc = 1236 kJ/mol = 26.8 kJ/g = 295.4 kcal/mol = 6.41 kcal/g[107]

Specific heat = 2.44 kJ/(kg·K)

Acid-base chemistry

Ethanol is a neutral molecule and the pH of a solution of ethanol in water is nearly 7.00. Ethanol can be quantitatively converted to its conjugate base, the ethoxide ion (CH3CH2O−), by reaction with an alkali metal such as sodium:[60]

- 2 CH3CH2OH + 2 Na → 2 CH3CH2ONa + H2

or a very strong base such as sodium hydride:

- CH3CH2OH + NaH → CH3CH2ONa + H2

The acidities of water and ethanol are nearly the same, as indicated by their pKa of 15.7 and 16 respectively. Thus, sodium ethoxide and sodium hydroxide exist in an equilibrium that is closely balanced:

- CH3CH2OH + NaOH ⇌ CH3CH2ONa + H2O

Halogenation

Ethanol is not used industrially as a precursor to ethyl halides, but the reactions are illustrative. Ethanol reacts with hydrogen halides to produce ethyl halides such as ethyl chloride and ethyl bromide via an SN2 reaction:

- CH3CH2OH + HCl → CH3CH2Cl + H2O

These reactions require a catalyst such as zinc chloride.[88] HBr requires refluxing with a sulfuric acid catalyst.[88] Ethyl halides can, in principle, also be produced by treating ethanol with more specialized halogenating agents, such as thionyl chloride or phosphorus tribromide.[60][88]

- CH3CH2OH + SOCl2 → CH3CH2Cl + SO2 + HCl

Upon treatment with halogens in the presence of base, ethanol gives the corresponding haloform (CHX3, where X = Cl, Br, I). This conversion is called the haloform reaction.[108] " An intermediate in the reaction with chlorine is the aldehyde called chloral, which forms chloral hydrate upon reaction with water:[109]

- 4 Cl2 + CH3CH2OH → CCl3CHO + 5 HCl

- CCl3CHO + H2O → CCl3C(OH)2H

Oxidation

Ethanol can be oxidized to acetaldehyde and further oxidized to acetic acid, depending on the reagents and conditions.[88] This oxidation is of no importance industrially, but in the human body, these oxidation reactions are catalyzed by the enzyme liver alcohol dehydrogenase. The oxidation product of ethanol, acetic acid, is a nutrient for humans, being a precursor to acetyl CoA, where the acetyl group can be spent as energy or used for biosynthesis.

Safety

Pure ethanol will irritate the skin and eyes.[110] Nausea, vomiting, and intoxication are symptoms of ingestion. Long-term use by ingestion can result in serious liver damage.[111] Atmospheric concentrations above one in a thousand are above the European Union occupational exposure limits.[111]

History

The fermentation of sugar into ethanol is one of the earliest biotechnologies employed by humans. The intoxicating effects of ethanol consumption have been known since ancient times. Ethanol has been used by humans since prehistory as the intoxicating ingredient of alcoholic beverages. Dried residue on 9,000-year-old pottery found in China suggests that Neolithic people consumed alcoholic beverages.[112]

The medieval Muslims used the distillation process extensively, and applied it to the distillation of alcohol. The Arab chemist Al-Kindi unambiguously described the distillation of wine in the 9th century.[113][114][115] The Persian physician, alchemist, polymath and philosopher Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (854 CE – 925 CE) is credited with the discovery of ethanol.[116] The process later spread from the Middle East to Italy.[113][117] Production of alcohol from distilled wine was later recorded by the School of Salerno alchemists in the 12th century.[118] Mention of absolute alcohol, in contrast with alcohol-water mixtures, was later made by Raymond Lull in the 14th century.[118]

In China, archaeological evidence indicates that the true distillation of alcohol began during the 12th century Jin or Southern Song dynasties.[119] A still has been found at an archaeological site in Qinglong, Hebei, dating to the 12th century.[119] In India, the true distillation of alcohol was introduced from the Middle East, and was in wide use in the Delhi Sultanate by the 14th century.[117]

In 1796, German-Russian chemist Johann Tobias Lowitz obtained pure ethanol by mixing partially purified ethanol (the alcohol-water azeotrope) with an excess of anhydrous alkali and then distilling the mixture over low heat.[120] French chemist Antoine Lavoisier described ethanol as a compound of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, and in 1807 Nicolas-Théodore de Saussure determined ethanol's chemical formula.[121][122] Fifty years later, Archibald Scott Couper published the structural formula of ethanol. It was one of the first structural formulas determined.[123]

Ethanol was first prepared synthetically in 1825 by Michael Faraday. He found that sulfuric acid could absorb large volumes of coal gas.[124] He gave the resulting solution to Henry Hennell, a British chemist, who found in 1826 that it contained "sulphovinic acid" (ethyl hydrogen sulfate).[125] In 1828, Hennell and the French chemist Georges-Simon Serullas independently discovered that sulphovinic acid could be decomposed into ethanol.[126][127] Thus, in 1825 Faraday had unwittingly discovered that ethanol could be produced from ethylene (a component of coal gas) by acid-catalyzed hydration, a process similar to current industrial ethanol synthesis.[128]

Ethanol was used as lamp fuel in the United States as early as 1840, but a tax levied on industrial alcohol during the Civil War made this use uneconomical. The tax was repealed in 1906.[129] Use as an automotive fuel dates back to 1908, with the Ford Model T able to run on petrol (gasoline) or ethanol.[130] It fuels some spirit lamps.

Ethanol intended for industrial use is often produced from ethylene.[131] Ethanol has widespread use as a solvent of substances intended for human contact or consumption, including scents, flavorings, colorings, and medicines. In chemistry, it is both a solvent and a feedstock for the synthesis of other products. It has a long history as a fuel for heat and light, and more recently as a fuel for internal combustion engines.

See also

References

- Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry : IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. p. 30. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-00001. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- Haynes, William M., ed. (2011). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 3.246. ISBN 1439855110.

- Ballinger P, Long FA (1960). "Acid Ionization Constants of Alcohols. II. Acidities of Some Substituted Methanols and Related Compounds1,2". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 82 (4): 795–798. doi:10.1021/ja01489a008.

- Arnett EM, Venkatasubramaniam KG (1983). "Thermochemical acidities in three superbase systems". J. Org. Chem. 48 (10): 1569–1578. doi:10.1021/jo00158a001.

- Lide DR, ed. (2012). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92 ed.). Boca Raton, FL.: CRC Press/Taylor and Francis. pp. 6–232.

- Lide DR, ed. (2008). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (89 ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. pp. 9–55.

- "MSDS Ethanol" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0262". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- "Ethanol – Compound Summary". The PubChem Project. USA: National Center for Biotechnology Information.

- Liebig J (1834). "Ueber die Constitution des Aethers und seiner Verbindungen" [On the constitution of ether and its compounds]. Annalen der Pharmacie (in German). 9 (22): 1–39. Bibcode:1834AnP...107..337L. doi:10.1002/andp.18341072202.

From page 18: "Bezeichnen wir die Kohlenwasserstoffverbindung 4C + 10H als das Radikal des Aethers mit E2 und nennen es Ethyl, ..." (Let us designate the hydrocarbon compound 4C + 10H as the radical of ether with E2 and name it ethyl ...).

- Harper, Douglas. "ethyl". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- For a report on the 1892 International Conference on Chemical Nomenclature, see:

- Armstrong H (1892). "The International Conference on Chemical Nomenclature". Nature. 46 (1177): 56–59. Bibcode:1892Natur..46...56A. doi:10.1038/046056c0.

- Armstrong's report is reprinted with the resolutions in English in: Armstrong H (1892). "The International Conference on Chemical Nomenclature". The Journal of Analytical and Applied Chemistry. 6 (1177): 390–400 (398). Bibcode:1892Natur..46...56A. doi:10.1038/046056c0.

The alcohols and the phenols will be called after the name of the hydrocarbon from which they are derived, terminated with the suffix ol (ex. pentanol, pentynol, etc.)

- OED; etymonline.com

- Pohorecky, Larissa A.; Brick, John (January 1988). "Pharmacology of ethanol". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 36 (2–3): 335–427. doi:10.1016/0163-7258(88)90109-X. PMID 3279433.

- McDonnell G, Russell AD (January 1999). "Antiseptics and disinfectants: activity, action, and resistance". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 12 (1): 147–79. doi:10.1128/CMR.12.1.147. PMC 88911. PMID 9880479.

- "Chemical Disinfectants | Disinfection & Sterilization Guidelines | Guidelines Library | Infection Control | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- "Why is 70% ethanol used for wiping microbiological working areas?". ResearchGate. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- "Ethanol". www.drugbank.ca. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- "Methanol poisoning". MedlinePlus. National Institute of Health. 30 January 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- Scalley R (September 2002). "Treatment of Ethylene Glycol Poisoning". American Family Physician. 66 (5): 807–813. PMID 12322772. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- "Alcohol Content in Common Preparations" (PDF). Medical Society of the State of New York. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- Adams KE, Rans TS (December 2013). "Adverse reactions to alcohol and alcoholic beverages". Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 111 (6): 439–45. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2013.09.016. PMID 24267355.

- Zuccotti GV, Fabiano V (July 2011). "Safety issues with ethanol as an excipient in drugs intended for pediatric use". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 10 (4): 499–502. doi:10.1517/14740338.2011.565328. PMID 21417862.

- Harger RN (1958). "The pharmacology and toxicology of alcohol". Journal of the American Medical Association. 167 (18): 2199–202. doi:10.1001/jama.1958.72990350014007. PMID 13563225.

- Wallner M, Olsen RW (2008). "Physiology and pharmacology of alcohol: the imidazobenzodiazepine alcohol antagonist site on subtypes of GABAA receptors as an opportunity for drug development?". British Journal of Pharmacology. 154 (2): 288–98. doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.32. PMC 2442438. PMID 18278063.

- Alcohol use and safe drinking. US National Institutes of Health.

- "Appendix B – Transportation Energy Data Book". Center for Transportation Analysis of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

- Eyidogan M, Ozsezen AN, Canakci M, Turkcan A (2010). "Impact of alcohol–gasoline fuel blends on the performance and combustion characteristics of an SI engine". Fuel. 89 (10): 2713–2720. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2010.01.032.

- Thomas, George: "Overview of Storage Development DOE Hydrogen Program" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2007. (99.6 KB). Livermore, CA. Sandia National Laboratories. 2000.

- Thomas G (2000). "Overview of Storage Development DOE Hydrogen Program" (PDF). Sandia National Laboratories. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- "Availability of Sources of E85". Clean Air Trust. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- Reel M (19 August 2006). "Brazil's Road to Energy Independence". The Washington Post.

- Chow D (26 April 2010). "Rocket Racing League Unveils New Flying Hot Rod". Space.com. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- Green R. "Model T Ford Club Australia (Inc.)". Archived from the original on 14 January 2014. Retrieved 24 June 2011.

- "Ethanol 101". American Coalition for Ethanol.

- Energy Future Coalition. "The Biofuels FAQs". The Biofuels Source Book. United Nations Foundation. Archived from the original on 19 February 2011.

- California Air Resources Board (October 1989). "Definition of a Low Emission Motor Vehicle in Compliance with the Mandates of Health and Safety Code Section 39037.05, second release". Archived from the original on 18 February 2018. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- Lowi A, Carter WP (March 1990). A Method for Evaluating the Atmospheric Ozone Impact of Actual Vehicle emissions. S.A.E. Technical Paper. Warrendale, PA.

- Jones TT (2008). "The Clean Fuels Report: A Quantitative Comparison Of Motor (engine) Fuels, Related Pollution and Technologies". researchandmarkets.com. Archived from the original on 9 September 2012.

- Tao R (16–20 August 2010). Electro-rheological Fluids and Magneto-rheological Suspensions. Proceedings of the 12th International Conference. Philadelphia, USA: World Scientific. ISBN 9789814340229.

- Biello D. "Want to Reduce Air Pollution? Don't Rely on Ethanol Necessarily". Scientific American. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- "Adoption of the Airborne Toxic Control Measure to Reduce Formaldehyde Emissions from Composite Wood Products". USA: Window and Door Manufacturers Association. 30 July 2008. Archived from the original on 9 March 2010.

- "2008 World Fuel Ethanol Production". U.S.: Renewable Fuels Association.

- "Tecnologia flex atrai estrangeiros". Agência Estado.

- "First Commercial U.S. Cellulosic Ethanol Biorefinery Announced". Renewable Fuels Association. 20 November 2006. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- Sweet sorghum for food, feed and fuel New Agriculturalist, January 2008.

- Developing a sweet sorghum ethanol value chain ICRISAT, 2013

- Horn M, Krupp F (16 March 2009). Earth: The Sequel: The Race to Reinvent Energy and Stop Global Warming. Physics Today. 62. pp. 63–65. Bibcode:2009PhT....62d..63K. doi:10.1063/1.3120901. ISBN 978-0-393-06810-8.

- Mechanics see ethanol damaging small engines, NBC News, 8 January 2008

- Clark, John D. (2017). Ingnition! An Informal History of Liquid Rocket Propellants. New Brunswick, N.j.: Rutgers University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-8135-9583-2.

- Darling D. "The Internet Encyclopedia of Science: V-2".

- Braeunig, Robert A. "Rocket Propellants." (Website). Rocket & Space Technology, 2006. Retrieved 23 August 2007.

- "A Brief History of Rocketry." NASA Historical Archive, via science.ksc.nasa.gov.

- Badwal SP, Giddey S, Kulkarni A, Goel J, Basu S (May 2015). "Direct ethanol fuel cells for transport and stationary applications – A comprehensive review". Applied Energy. 145: 80–103. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.02.002.

- "Can Ethanol Fireplaces Be Cozy?". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- "Your Guide to Ethanol Extraction". Cannabis Business Times. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- Lide DR, ed. (2000). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics 81st edition. CRC press. ISBN 978-0-8493-0481-1.

- "What is the triple point of alcohol?". Webanswers.com. 31 December 2010. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013.

- Windholz M (1976). The Merck index: an encyclopedia of chemicals and drugs (9th ed.). Rahway, N.J., U.S.A: Merck. ISBN 978-0-911910-26-1.

- Morrison RT, Boyd RN (1972). Organic Chemistry (2nd ed.). Allyn and Bacon, inc. ISBN 978-0-205-08452-4.

- Dahlmann U, Schneider GM (1989). "(Liquid + liquid) phase equilibria and critical curves of (ethanol + dodecane or tetradecane or hexadecane or 2,2,4,4,6,8,8-heptamethylnonane) from 0.1 MPa to 120.0 MPa". J Chem Thermodyn. 21 (9): 997–1004. doi:10.1016/0021-9614(89)90160-2.

- "Ethanol". Encyclopedia of chemical technology. 9. 1991. p. 813.

- Costigan MJ, Hodges LJ, Marsh KN, Stokes RH, Tuxford CW (1980). "The Isothermal Displacement Calorimeter: Design Modifications for Measuring Exothermic Enthalpies of Mixing". Aust. J. Chem. 33 (10): 2103. Bibcode:1982AuJCh..35.1971I. doi:10.1071/CH9802103.

- Lei Z, Wang H, Zhou R, Duan Z (2002). "Influence of salt added to solvent on extractive distillation". Chem. Eng. J. 87 (2): 149–156. doi:10.1016/S1385-8947(01)00211-X.

- Pemberton RC, Mash CJ (1978). "Thermodynamic properties of aqueous non-electrolyte mixtures II. Vapour pressures and excess Gibbs energies for water + ethanol at 303.15 to 363.15 K determined by an accurate static method". J Chem Thermodyn. 10 (9): 867–888. doi:10.1016/0021-9614(78)90160-X.

- Merck Index of Chemicals and Drugs, 9th ed.; monographs 6575 through 6669

- "Flash Point and Fire Point". Nttworldwide.com. Archived from the original on 14 December 2010.

- NFPA 325: Guide to Fire Hazard Properties of Flammable Liquids, Gases, and Volatile Solids. Quincy, MA.: National Fire Protection Association (NFPA). 1 January 1994.

- "49 CFR § 173.120 - Class 3 - Definitions". Code of Federal Regulation. Title 49.

a flammable liquid (Class 3) means a liquid having a flash point of not more than 60 °C (140 °F)

- Martínez, P.J.; Rus, E.; Compaña, J.M. "Flash Point Determination of Binary Mixtures of Alcohols, Ketones and Water". Departamento de Ingeniería Química. Facultad de Ciencias.: 3.

Page3, Table 4

- "49 CFR § 172.101 - Purpose and use of hazardous materials table". Code of Federal Regulation. Title 49.

Hazardous materials descriptions and proper shipping names: Ethanol or Ethyl alcohol or Ethanol solutions or Ethyl alcohol solutions; Hazard class or Division: 3; Identification Numbers: UN1170; PG: II; Label Codes: 3;

- Ha, Dong-Myeong; Park, Sang Hun; Lee, Sungjin (April 2015). "The Measurement of Flash Point of Water-Methanol and Water-Ethanol Systems Using Seta Flash Closed Cup Tester". Fire Science and Engineering. 29 (2): 39–43. doi:10.7731/KIFSE.2015.29.2.039.

Page 4, Table 3

- "Flash points of ethanol-based water solutions". Engineeringtoolbox.com. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- Dudley R (August 2004). "Ethanol, fruit ripening, and the historical origins of human alcoholism in primate frugivory". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 44 (4): 315–23. doi:10.1093/icb/44.4.315. PMID 21676715.

- Graber C (2008). "Fact or Fiction?: Animals Like to Get Drunk". Scientific American. Retrieved 23 July 2010.

- Leblová S, Sinecká E, Vaníčková V (1974). "Pyruvate metabolism in germinating seeds during natural anaerobiosis". Biologia Plantarum. 16 (6): 406–411. doi:10.1007/BF02922229.

- Schriver A, Schriver-Mazzuoli L, Ehrenfreund P, d'Hendecourt L (2007). "One possible origin of ethanol in interstellar medium: Photochemistry of mixed CO2–C2H6 films at 11 K. A FTIR study". Chemical Physics. 334 (1–3): 128–137. Bibcode:2007CP....334..128S. doi:10.1016/j.chemphys.2007.02.018.

- Turner C, Spanel P, Smith D (2006). "A longitudinal study of ethanol and acetaldehyde in the exhaled breath of healthy volunteers using selected-ion flow-tube mass spectrometry". Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 20 (1): 61–8. Bibcode:2006RCMS...20...61T. doi:10.1002/rcm.2275. PMID 16312013.

- Doucleff M (17 September 2013). "Auto-Brewery Syndrome: Apparently, You Can Make Beer In Your Gut". NPR.

- Mills GA, Ecklund EE (1987). "Alcohols as Components of Transportation Fuels". Annual Review of Energy. 12: 47–80. doi:10.1146/annurev.eg.12.110187.000403.

- Wittcoff HA, Reuben BG, Plotkin JS (2004). Industrial Organic Chemicals. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 136–. ISBN 978-0-471-44385-8.

- Roberts JD, Caserio MC (1977). Basic Principles of Organic Chemistry. W. A. Benjamin, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8053-8329-4.

- Kosaric N, Duvnjak Z, Farkas A, Sahm H, Bringer-Meyer S, Goebel O, Mayer D (2011). "Ethanol". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. pp. 1–72. doi:10.1002/14356007.a09_587.pub2. ISBN 9783527306732.(subscription required)

- "Ethanol". Encyclopedia of chemical technology. 9. 1991. p. 82.

- Ethanol. essentialchemicalindustry.org

- Harrison, Tim (May 2014) Catalysis Web Pages for Pre-University Students V1_0. Bristol ChemLabS, School of Chemistry, University of Bristol

- Lodgsdon JE (1991). "Ethanol". In Howe-Grant, Mary, Kirk, Raymond E., Othmer, Donald F., Kroschwitz, Jacqueline I. (eds.). Encyclopedia of chemical technology. 9 (4th ed.). New York: Wiley. p. 817. ISBN 978-0-471-52669-8.

- Streitwieser A, Heathcock CH (1976). Introduction to Organic Chemistry. MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-02-418010-0.

- Shu Xia and Theodore Wiesner (June 2008). Biological production of ethanol from CO2 produced by a fossil-fueled power plant. 2008 3rd IEEE Conference on Industrial Electronics and Applications. pp. 1814–1819. doi:10.1109/ICIEA.2008.4582832. ISBN 978-1-4244-1717-9.

- Liew F, Henstra AM, Köpke M, Winzer K, Simpson SD, Minton NP (March 2017). "Metabolic engineering of Clostridium autoethanogenum for selective alcohol production". Metabolic Engineering. 40: 104–114. doi:10.1016/j.ymben.2017.01.007. PMC 5367853. PMID 28111249.

- "Solar-to-Fuel System Recycles CO2 for Ethanol and Ethylene". News Center. 18 September 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- "TU Delft researcher makes alcohol out of thin air". TU Delft. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- Ma, Ming; et al. (April 2016). "Controllable Hydrocarbon Formation from the Electrochemical Reduction of CO2 over Cu Nanowire Arrays". Angewandte Chemie. 55 (23): 6680–4. doi:10.1002/anie.201601282. PMID 27098996.

- Menetrez MY (July 2012). "An overview of algae biofuel production and potential environmental impact" (PDF). Environmental Science & Technology. 46 (13): 7073–85. Bibcode:2012EnST...46.7073M. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.665.3435. doi:10.1021/es300917r. PMID 22681590. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- Clines T (July 2006). "Brew Better Ethanol". Popular Science Online. Archived from the original on 3 November 2007.

- Chemists, American Association of Cereal (1986). Advances in Cereal Science and Technology. American Association of Cereal Chemists, Incorporated. ISBN 9780913250457.

- Song Y, Peng R, Hensley DK, Bonnesen PV, Liang L, Wu Z, Meyer HM, Chi M, Ma C, Sumpter BG, Rondinone AJ (2016). "High-Selectivity Electrochemical Conversion of CO2 to Ethanol using a Copper Nanoparticle/N-Doped Graphene Electrode". ChemistrySelect. 1 (Preprint): 6055–6061. doi:10.1002/slct.201601169.

- Jeong J, Jeon H, Ko K, Chung B, Choi G (2012). "Production of anhydrous ethanol using various PSA (Pressure Swing Adsorption) processes in pilot plant". Renewable Energy. 42: 41–45. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2011.09.027.

- "U-M Program to Reduce the Consumption of Tax-free Alcohol; Denatured Alcohol a Safer, Less Expensive Alternative" (PDF). University of Michigan. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2007. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- Great Britain (2005). The Denatured Alcohol Regulations 2005. Statutory Instrument 2005 No. 1524.

- Bansal RK, Bernthsen A (2003). A Textbook of Organic Chemistry. New Age International Limited. pp. 402–. ISBN 978-81-224-1459-2.

- Christian GD (2004). "Solvents for Spectrometry". Analytical chemistry. 1 (6th ed.). Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons. p. 473. ISBN 978-0471214724.

- Andrews S (1 August 2007). Textbook Of Food & Bevrge Mgmt. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. pp. 268–. ISBN 978-0-07-065573-7.

- Kunkee RE, Amerine MA (July 1968). "Sugar and alcohol stabilization of yeast in sweet wine". Applied Microbiology. 16 (7): 1067–75. doi:10.1128/AEM.16.7.1067-1075.1968. PMC 547590. PMID 5664123.

- Zimmermann, Heinz; Walz, Roland (2008). "Ethylene". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a10_045.pub3. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- Rossini FD (1937). "Heats of Formation of Simple Organic Molecules". Ind. Eng. Chem. 29 (12): 1424–1430. doi:10.1021/ie50336a024.

- Calculated from heats of formation from CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 49th Edition, 1968–1969.

- Chakrabartty SK (1978). Trahanovsky WS (ed.). Oxidation in Organic Chemistry. New York: Academic Press. pp. 343–370.

- Reinhard J, Kopp E, McKusick BC, Röderer G, Bosch A, Fleischmann G (2007). "Chloroacetaldehydes". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a06_527.pub2. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- Minutes of Meeting. Technical Committee on Classification and Properties of Hazardous Chemical Data ( 12–13 January 2010).

- "Safety data for ethyl alcohol". University of Oxford. 9 May 2008. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- Roach J (18 July 2005). "9,000-Year-Old Beer Re-Created From Chinese Recipe". National Geographic News. Retrieved 3 September 2007.

- al-Hassan AY (2001). Science and Technology in Islam: Technology and applied sciences. UNESCO. pp. 65–69.

- Hassan AY. "Alcohol and the Distillation of Wine in Arabic Sources". History of Science and Technology in Islam. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- "Liquid fire – The Arabs discovered how to distil alcohol. They still do it best, say some". The Economist. 18 December 2003.

- Schlosser, Stefan (2011). "Distillation – from Bronze Age till today". Conference: 38th Int. Conf. SSCHE, At Tatranské Matliare (SK).

- Habib, Irfan (2011). Economic History of Medieval India, 1200-1500. Pearson Education India. pp. 55–. ISBN 978-81-317-2791-1.

- Forbes RJ (1948). A short history of the art of distillation. Brill. p. 89. ISBN 978-9004006171.

- Haw SG (2006). "Wine, women and poison". Marco Polo in China. Routledge. pp. 147–148. ISBN 978-1-134-27542-7. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

The earliest possible period seems to be the Eastern Han dynasty... the most likely period for the beginning of true distillation of spirits for drinking in China is during the Jin and Southern Song dynasties

- Lowitz T (1796). "Anzeige eines, zur volkommen Entwasserung des Weingeistes nothwendig zu beobachtenden, Handgriffs" [Report of a task that must be done for the complete dehydration of wine spirits [i.e., alcohol-water azeotrope])]. Chemische Annalen für die Freunde der Naturlehre, Aerznengelartheit, Haushaltungskunde und Manufakturen (in German). 1: 195–204.

See pp. 197–198: Lowitz dehydrated the azeotrope by mixing it with a 2:1 excess of anhydrous alkali and then distilling the mixture over low heat.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 525–527.

- de Saussure T (1807). "Mémoire sur la composition de l'alcohol et de l'éther sulfurique". Journal de Physique, de Chimie, d'Histoire Naturelle et des Arts. 64: 316–354. In his 1807 paper, Saussure determined ethanol's composition only roughly; a more accurate analysis of ethanol appears on page 300 of his 1814 paper: de Saussure, Théodore (1814). "Nouvelles observations sur la composition de l'alcool et de l'éther sulfurique". Annales de Chimie et de Physique. 89: 273–305.

- Couper AS (1858). "On a new chemical theory" (online reprint). Philosophical Magazine. 16 (104–16). Retrieved 3 September 2007.

- Faraday M (1825). "On new compounds of carbon and hydrogen, and on certain other products obtained during the decomposition of oil by heat". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 115: 440–466. doi:10.1098/rstl.1825.0022. In a footnote on page 448, Faraday notes the action of sulfuric acid on coal gas and coal-gas distillate; specifically, "The [sulfuric] acid combines directly with carbon and hydrogen; and I find when [the resulting compound is] united with bases [it] forms a peculiar class of salts, somewhat resembling the sulphovinates [i.e., ethyl sulfates], but still different from them."

- Hennell H (1826). "On the mutual action of sulphuric acid and alcohol, with observations on the composition and properties of the resulting compound". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 116: 240–249. doi:10.1098/rstl.1826.0021. On page 248, Hennell mentions that Faraday gave him some sulfuric acid in which coal gas had dissolved and that he (Hennell) found that it contained "sulphovinic acid" (ethyl hydrogen sulfate).

- Hennell H (1828). "On the mutual action of sulfuric acid and alcohol, and on the nature of the process by which ether is formed". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 118: 365–371. doi:10.1098/rstl.1828.0021. On page 368, Hennell produces ethanol from "sulfovinic acid" (ethyl hydrogen sulfate).

- Sérullas G (1828). Guyton de Morveau L, Gay-Lussac JL, Arago F, Michel Eugène Chevreul, Marcellin Berthelot, Éleuthère Élie Nicolas Mascart, Albin Haller (eds.). "De l'action de l'acide sulfurique sur l'alcool, et des produits qui en résultent". Annales de Chimie et de Physique. 39: 152–186. On page 158, Sérullas mentions the production of alcohol from "sulfate acid d'hydrogène carboné" (hydrocarbon acid sulfate).

- In 1855, the French chemist Marcellin Berthelot confirmed Faraday's discovery by preparing ethanol from pure ethylene. Berthelot M (1855). Arago F, Gay-Lussac JL (eds.). "Sur la formation de l'alcool au moyen du bicarbure d'hydrogène (On the formation of alcohol by means of ethylene)". Annales de Chimie et de Physique. 43: 385–405. (Note: The chemical formulas in Berthelot's paper are wrong because chemists at that time used the wrong atomic masses for the elements; e.g., carbon (6 instead of 12), oxygen (8 instead of 16), etc.)

- Siegel R (15 February 2007). "Ethanol, Once Bypassed, Now Surging Ahead". NPR. Retrieved 22 September 2007.

- DiPardo J. "Outlook for Biomass Ethanol Production and Demand" (PDF). United States Department of Energy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2007.

- Myers RL, Myers RL (2007). The 100 most important chemical compounds: a reference guide. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-313-33758-1.

Further reading

- Boyce JM, Pittet D (2003). "Hand Hygiene in Healthcare Settings". Atlanta, Georgia, United States: Centers for Disease Control..

- Onuki S, Koziel JA, van Leeuwen J, Jenks WS, Grewell D, Cai L (June 2008). Ethanol production, purification, and analysis techniques: a review. 2008 ASABE Annual International Meeting. Providence, RI. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- "Explanation of US denatured alcohol designations". Sci-toys.

External links

| Look up alcohol or ethanol in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ethanol. |

- Alcohol (Ethanol) at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)

- International Labour Organization ethanol safety information

- National Pollutant Inventory – Ethanol Fact Sheet

- CDC – NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards – Ethyl Alcohol

- National Institute of Standards and Technology chemical data on ethanol

- Chicago Board of Trade news and market data on ethanol futures

- Calculation of vapor pressure, liquid density, dynamic liquid viscosity, surface tension of ethanol

- Ethanol History A look into the history of ethanol

- ChemSub Online: Ethyl alcohol

- Industrial ethanol production process flow diagram using ethylene and sulphuric acid