Ford Model T

The Ford Model T (colloquially known as the Tin Lizzie, Leaping Lena, jitney or flivver) is an automobile produced by Ford Motor Company from October 1, 1908, to May 26, 1927.[8][9] It is generally regarded as the first affordable automobile, which made car travel available to middle-class Americans. The relatively low price was partly the result of Ford's efficient fabrication, including assembly line production instead of individual hand crafting.[10]

| Ford Model T | |

|---|---|

1925 Ford Model T Touring | |

| Overview | |

| Manufacturer | Ford Motor Company |

| Production | 1908–1927 |

| Assembly | List

|

| Designer | Henry Ford, Childe Harold Wills, Joseph A. Galamb and Eugene Farkas |

| Body and chassis | |

| Class | Full-size Ford, economy car |

| Body style | List

|

| Layout | FR layout |

| Powertrain | |

| Engine | 177 C.I.D. (2.9 L) 20 hp I4 |

| Transmission | 2-speed planetary gear |

| Dimensions | |

| Wheelbase | 100.0 in (2,540 mm) |

| Length | 134 in (3,404 mm) |

| Width | 1,676 mm (66.0 in) (1912 Roadster)[7] |

| Height | 1,860 mm (73.2 in) (1912 Roadster)[7] |

| Curb weight | 1,200–1,650 lb (540–750 kg) |

| Chronology | |

| Predecessor | Ford Model N (1906–1908) |

| Successor | Ford Model A (1927–31) |

The Ford Model T was named the most influential car of the 20th century in the 1999 Car of the Century competition, ahead of the BMC Mini, Citroën DS, and Volkswagen Type 1.[11] Ford's Model T was successful not only because it provided inexpensive transportation on a massive scale, but also because the car signified innovation for the rising middle class and became a powerful symbol of the United States age of modernization.[12] With 16.5 million sold, it stood eighth on the top ten list of most sold cars of all time, as of 2012.[13]

Introduction

Although automobiles had been produced from the 1880s, until the Model T was introduced in 1908, they were mostly scarce, expensive, and often unreliable. Positioned as reliable, easily maintained, mass-market transportation, it was a runaway success. In a matter of days after the release, 15,000 orders had been placed.[14] The first production Model T was built on August 12, 1908[15] and left the factory on September 27, 1908, at the Ford Piquette Avenue Plant in Detroit, Michigan. On May 26, 1927, Henry Ford watched the 15 millionth Model T Ford roll off the assembly line at his factory in Highland Park, Michigan.[16]

Henry Ford conceived a series of cars between the founding of the company in 1903 and the introduction of the Model T. Ford named his first car the Model A and proceeded through the alphabet up through the Model T, twenty models in all. Not all the models went into production. The production model immediately before the Model T was the Model S,[17] an upgraded version of the company's largest success to that point, the Model N. The follow-up to the Model T was the Ford Model A, rather than the "Model U". The company publicity said this was because the new car was such a departure from the old that Ford wanted to start all over again with the letter A.

The Model T was Ford's first automobile mass-produced on moving assembly lines with completely interchangeable parts, marketed to the middle class.[18] Henry Ford said of the vehicle:

I will build a motor car for the great multitude. It will be large enough for the family, but small enough for the individual to run and care for. It will be constructed of the best materials, by the best men to be hired, after the simplest designs that modern engineering can devise. But it will be so low in price that no man making a good salary will be unable to own one – and enjoy with his family the blessing of hours of pleasure in God's great open spaces.[19]

Although credit for the development of the assembly line belongs to Ransom E. Olds, with the first mass-produced automobile, the Oldsmobile Curved Dash, having begun in 1901, the tremendous advances in the efficiency of the system over the life of the Model T can be credited almost entirely to the vision of Ford and his engineers.[20]

Characteristics

The Model T was designed by Childe Harold Wills, and Hungarian immigrants Joseph A. Galamb[21] and Eugene Farkas.[22] Henry Love, C. J. Smith, Gus Degner and Peter E. Martin were also part of the team.[23] Production of the Model T began in the third quarter of 1908.[24] Collectors today sometimes classify Model Ts by build years and refer to these as "model years", thus labeling the first Model Ts as 1909 models. This is a retroactive classification scheme; the concept of model years as understood today did not exist at the time. The nominal model designation was "Model T", although design revisions did occur during the car's two decades of production.

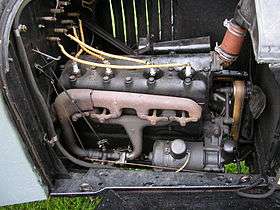

Engine

The Model T had a front-mounted 177-cubic-inch (2.9 L) inline four-cylinder engine, producing 20 hp (15 kW), for a top speed of 40–45 mph (64–72 km/h).[25] According to Ford Motor Company, the Model T had fuel economy on the order of 13–21 mpg‑US (16–25 mpg‑imp; 18–11 L/100 km).[26] The engine was capable of running on gasoline, kerosene, or ethanol,[27][28] although the decreasing cost of gasoline and the later introduction of Prohibition made ethanol an impractical fuel for most users. The engines of the first 2,447 units were cooled with water pumps; the engines of unit 2,448 and onward, with a few exceptions prior to around unit 2,500, were cooled by thermosiphon action.[29]

The ignition system used in the Model T was an unusual one, with a low-voltage magneto incorporated in the flywheel, supplying alternating current to trembler coils to drive the spark plugs. This was closer to that used for stationary gas engines than the expensive high-voltage ignition magnetos that were used on some other cars. This ignition also made the Model T more flexible as to the quality or type of fuel it used. The system did not need a starting battery, since proper hand-cranking would generate enough current for starting. Electric lighting powered by the magneto was adopted in 1915, replacing acetylene and oil lamps, but electric starting was not offered until 1919.[30]

The Model T engine was produced for replacement needs, as well as stationary and marine applications until 1941, well after production of the Model T had ended.

The Fordson Model F tractor engine, that was designed about a decade later, was very similar to, but larger than, the Model T engine.[31]

Transmission and drive train

.jpg)

The Model T was a rear-wheel drive vehicle. Its transmission was a planetary gear type billed as "three speed". In today's terms it would be considered a two-speed, because one of the three speeds was reverse.

The Model T's transmission was controlled with three floor-mounted pedals and a lever mounted to the road side of the driver's seat. The throttle was controlled with a lever on the steering wheel. The left-hand pedal was used to engage the transmission. With the floor lever in either the mid position or fully forward and the pedal pressed and held forward, the car entered low gear. When held in an intermediate position, the car was in neutral. If the left pedal was released, the Model T entered high gear, but only when the lever was fully forward – in any other position, the pedal would only move up as far as the central neutral position. This allowed the car to be held in neutral while the driver cranked the engine by hand. The car could thus cruise without the driver having to press any of the pedals.

In the first 800 units, reverse was engaged with a lever; all units after that used the central pedal, which was used to engage reverse gear when the car was in neutral.[29] The right-hand pedal operated the transmission brake – there were no brakes on the wheels. The floor lever also controlled the parking brake, which was activated by pulling the lever all the way back. This doubled as an emergency brake.

Although it was uncommon, the drive bands could fall out of adjustment, allowing the car to creep, particularly when cold, adding another hazard to attempting to start the car: a person cranking the engine could be forced backward while still holding the crank as the car crept forward, although it was nominally in neutral. As the car utilized a wet clutch, this condition could also occur in cold weather, when the thickened oil prevents the clutch discs from slipping freely. Power reached the differential through a single universal joint attached to a torque tube which drove the rear axle; some models (typically trucks, but available for cars, as well) could be equipped with an optional two-speed Ruckstell rear axle shifted by a floor-mounted lever which provided an underdrive gear for easier hill climbing. The heavy-duty Model TT truck chassis came with a special worm gear rear differential with lower gearing than the normal car and truck, giving more pulling power but a lower top speed (the frame was also stronger; the cab and engine were the same). A Model TT is easily identifiable by the cylindrical housing for the worm-drive over the axle differential. All gears were vanadium steel running in an oil bath.

Transmission bands and linings

Two main types of band lining material were used:[32]

- Cotton – Cotton woven linings were the original type fitted and specified by Ford. Generally, the cotton lining is "kinder" to the drum surface, with damage to the drum caused only by the retaining rivets scoring the drum surface. Although this in itself did not pose a problem, a dragging band resulting from improper adjustment caused overheating of the transmission and engine, diminished power, and – in the case of cotton linings – rapid destruction of the band lining.

- Wood – Wooden linings were originally offered as a "longer life" accessory part during the life of the Model T. They were a single piece of steam bent wood and metal wire, fitted to the normal Model T transmission band.[33] These bands give a very different feel to the pedals, with much more of a "bite" feel. The sensation is of a definite "grip" of the drum and seemed to noticeably increase the feel, in particular of the brake drum.

Suspension and wheels

Model T suspension employed a transversely mounted semi-elliptical spring for each of the front and rear beam axles which allowed a great deal of wheel movement to cope with the dirt roads of the time.

The front axle was drop forged as a single piece of vanadium steel. Ford twisted many axles through eight full rotations (2880 degrees) and sent them to dealers to be put on display to demonstrate its superiority. The Model T did not have a modern service brake. The right foot pedal applied a band around a drum in the transmission, thus stopping the rear wheels from turning. The previously mentioned parking brake lever operated band brakes acting on the inside of the rear brake drums, which were an integral part of the rear wheel hubs. Optional brakes that acted on the outside of the brake drums were available from aftermarket suppliers.

Wheels were wooden artillery wheels, with steel welded-spoke wheels available in 1926 and 1927.

Tires were pneumatic clincher type, 30 in (76 cm) in diameter, 3.5 in (8.9 cm) wide in the rear, 3 in (7.6 cm) in the front. Clinchers needed much higher pressure than today's tires, typically 60 psi (410 kPa), to prevent them from leaving the rim at speed. Horseshoe nails on the roads, together with the high pressure, made flat tires a common problem.

Balloon tires became available in 1925. They were 21 in × 4.5 in (53 cm × 11 cm) all around. Balloon tires were closer in design to today's tires, with steel wires reinforcing the tire bead, making lower pressure possible – typically 35 psi (240 kPa) – giving a softer ride. The steering gear ratio was changed from 4:1 to 5:1 with the introduction of balloon tires.[34] The old nomenclature for tire size changed from measuring the outer diameter to measuring the rim diameter so 21 in (530 mm) (rim diameter) × 4.5 in (110 mm) (tire width) wheels has about the same outer diameter as 30 in (76 cm) clincher tires. All tires in this time period used an inner tube to hold the pressurized air; tubeless tires were not generally in use until much later.

Wheelbase was 100 inches (254 cm) and standard track width was 56 inch (142 cm); 60 inch (152 cm) track could be obtained on special order, "for Southern roads", identical to the pre-Civil War track gauge for many railroads in the former Confederacy. The standard 56 inch track being very near the standard 4 foot 8 1⁄2 inch railroad track gauge meant that Model Ts could be and frequently were, fitted with flanged wheels and used as railway vehicles; the availability of a 60in (5ft) version meant the same could be done on the few remaining Southern 5ft railways (these being the only nonstandard lines remaining, except for a few narrow-gauge lines of various sizes). Although a Model T could be adapted to run on track as narrow as 2ft gauge (Wiscasset, Waterville and Farmington RR, Maine has one), this was a more complex alteration.

Colors

By 1918, half of all the cars in the U.S. were Model Ts. In his autobiography, Ford reports that in 1909 he told his management team, "Any customer can have a car painted any color that he wants so long as it is black."[35]

However, in the first years of production from 1908 to 1913, the Model T was not available in black[36] but rather only gray, green, blue, and red. Green was available for the touring cars, town cars, coupes, and Landaulets. Gray was only available for the town cars, and red only for the touring cars. By 1912, all cars were being painted midnight blue with black fenders. Only in 1914 was the "any color so long as it is black" policy finally implemented. It is often stated Ford suggested the use of black from 1914 to 1925 due to the low cost, durability, and faster drying time of black paint in that era. Paint choices in the American automotive industry, as well as in others (including locomotives, furniture, bicycles, and the rapidly expanding field of electrical appliances), were shaped by the development of the chemical industry. These included the disruption of dye sources during World War I and the advent, in the mid-1920s, of new nitrocellulose lacquers that were faster-drying and more scratch-resistant, and obviated the need for multiple coats;[37]:261–301 understanding the choice of paints for the Model T era and the years immediately following requires an understanding of the contemporary chemical industry.[37]

During the lifetime production of the Model T, over 30 types of black paint were used on various parts of the car.[36] These were formulated to satisfy the different means of applying the paint to the various parts, and had distinct drying times, depending on the part, paint, and method of drying.

Body

Although Ford classified the Model T with a single letter designation throughout its entire life and made no distinction by model years, enough significant changes to the body were made over the production life that the car may be classified into several style generations. Among the most immediately visible and identifiable changes were in the hood and cowl areas, although many other modifications were made to the vehicle.

- 1909–1914 – Characterized by a nearly straight, five-sided hood, with a flat top containing a center hinge and two side sloping sections containing the folding hinges. The firewall was flat from the windshield down with no distinct cowl.

- 1915–1916 – The hood design was nearly the same five-sided design with the only obvious change being the addition of louvers to the vertical sides. A significant change to the cowl area occurred with the windshield relocated significantly behind the firewall and joined with a compound-contoured cowl panel. In these years electric headlights replaced carbide headlights.

- 1917–1923 – The hood design was changed to a tapered design with a curved top. The folding hinges were now located at the joint between the flat sides and the curved top. This is sometime referred to as the "low hood" to distinguish it from the later hoods. The back edge of the hood now met the front edge of the cowl panel so that no part of the flat firewall was visible outside of the hood. This design was used the longest and during the highest production years, accounting for about half of the total number of Model Ts built.

- 1923–1925 – This change was made during the 1923 calendar year, so models built earlier in the year have the older design, while later vehicles have the newer design. The taper of the hood was increased and the rear section at the firewall is about an inch taller and several inches wider than the previous design. While this is a relatively minor change, the parts between the third and fourth generations are not interchangeable.

- 1926–1927 – This design change made the greatest difference in the appearance of the car. The hood was again enlarged, with the cowl panel no longer a compound curve and blended much more with the line of the hood. The distance between the firewall and the windshield was also increased significantly. This style is sometimes referred to as the "high hood".

The styling on the last "generation" was a preview for the following Model A, but the two models are visually quite different, as the body on the A was much wider and had curved doors as opposed to the flat doors on the T.

Diverse applications

When the Model T was designed and introduced, the infrastructure of the world was quite different from today's. Pavement was a rarity except for sidewalks and a few big-city streets. (The sense of the term "pavement" as equivalent with "sidewalk" comes from that era, when streets and roads were generally dirt and sidewalks were a paved way to walk along them.) Agriculture was the occupation of many people. Power tools were scarce outside factories, as were power sources for them; electrification, like pavement, was found usually only in larger towns. Rural electrification and motorized mechanization were embryonic in some regions and nonexistent in most. Henry Ford oversaw the requirements and design of the Model T based on contemporary realities. Consequently, the Model T was (intentionally) almost as much a tractor and portable engine as it was an automobile. It has always been well regarded for its all-terrain abilities and ruggedness. It could travel a rocky, muddy farm lane, cross a shallow stream, climb a steep hill, and be parked on the other side to have one of its wheels removed and a pulley fastened to the hub for a flat belt to drive a bucksaw, thresher, silo blower, conveyor for filling corn cribs or haylofts, baler, water pump, electrical generator, and many other applications. One unique application of the Model T was shown in the October 1922 issue of Fordson Farmer magazine. It showed a minister who had transformed his Model T into a mobile church, complete with small organ.[38]

During this era, entire automobiles (including thousands of Model Ts) were even hacked apart by their owners and reconfigured into custom machinery permanently dedicated to a purpose, such as homemade tractors and ice saws.[39] Dozens of aftermarket companies sold prefab kits to facilitate the T's conversion from car to tractor.[40] The Model T had been around for a decade before the Fordson tractor became available (1917–18), and many Ts had been converted for field use. (For example, Harry Ferguson, later famous for his hitches and tractors, worked on Eros Model T tractor conversions before he worked with Fordsons and others.) During the next decade, Model T tractor conversion kits were harder to sell, as the Fordson and then the Farmall (1924), as well as other light and affordable tractors, served the farm market. But during the Depression (1930s), Model T tractor conversion kits had a resurgence, because by then used Model Ts and junkyard parts for them were plentiful and cheap.[41]

Like many popular car engines of the era, the Model T engine was also used on home-built aircraft (such as the Pietenpol Sky Scout) and motorboats.

An armored-car variant (called the FT-B) was developed in Poland in 1920 due to the high demand during the Polish-Soviet war in 1920.

Many Model Ts were converted into vehicles which could travel across heavy snows with kits on the rear wheels (sometimes with an extra pair of rear-mounted wheels and two sets of continuous track to mount on the now-tandemed rear wheels, essentially making it a half-track) and skis replacing the front wheels. They were popular for rural mail delivery for a time. The common name for these conversions of cars and small trucks was "snowflyers". These vehicles were extremely popular in the northern reaches of Canada, where factories were set up to produce them.[42]

A number of companies built Model T–based railcars.[43] In The Great Railway Bazaar, Paul Theroux mentions a rail journey in India on such a railcar. The New Zealand Railways Department's RM class included a few.

The American LaFrance company modified more than 900 Model T's for use in firefighting, adding tanks, hoses, tools and a bell.[44] Model T fire engines were in service in North America, Europe, and Australia.[45][44] A 1919 Model T equipped to fight chemical fires has been restored and is on display at the North Charleston Fire Museum in South Carolina.[46]

Production

Mass production

The knowledge and skills needed by a factory worker were reduced to 84 areas. When introduced, the T used the building methods typical at the time, assembly by hand, and production was small. The Ford Piquette Avenue Plant could not keep up with demand for the Model T, and only 11 cars were built there during the first full month of production. More and more machines were used to reduce the complexity within the 84 defined areas. In 1910, after assembling nearly 12,000 Model Ts, Henry Ford moved the company to the new Highland Park complex. During this time the Model T production system (including the supply chain) transitioned into an iconic example of assembly line production.[18][47] In subsequent decades it would also come to be viewed as the classic example of the rigid, first-generation version of assembly line production, as opposed to flexible mass production[18] of higher quality products.[47]

As a result, Ford's cars came off the line in three-minute intervals, much faster than previous methods, reducing production time from 12.5 hours before to 93 minutes by 1914, while using less manpower.[48] In 1914, Ford produced more cars than all other automakers combined. The Model T was a great commercial success, and by the time Ford made its 10 millionth car, half of all cars in the world were Fords. It was so successful Ford did not purchase any advertising between 1917 and 1923; instead, the Model T became so famous, people considered it a norm. More than 15 million Model Ts were manufactured in all, reaching a rate of 9,000 to 10,000 cars a day in 1925, or 2 million annually,[49][50][51] more than any other model of its day, at a price of just $260. Total Model T production was finally surpassed by the Volkswagen Beetle on February 17, 1972.

Henry Ford's ideological approach to Model T design was one of getting it right and then keeping it the same; he believed the Model T was all the car a person would, or could, ever need. As other companies offered comfort and styling advantages, at competitive prices, the Model T lost market share and became barely profitable.[47] Design changes were not as few as the public perceived, but the idea of an unchanging model was kept intact. Eventually, on May 26, 1927, Ford Motor Company ceased US production[52][53][54] and began the changeovers required to produce the Model A.[55] Some of the other Model T factories in the world continued a short while.[56]

Model T engines continued to be produced until August 4, 1941. Almost 170,000 were built after car production stopped, as replacement engines were required to service already produced vehicles. Racers and enthusiasts, forerunners of modern hot rodders, used the Model T's block to build popular and cheap racing engines, including Cragar, Navarro, and famously the Frontenacs ("Fronty Fords")[53] of the Chevrolet brothers, among many others.

The Model T employed some advanced technology, for example, its use of vanadium steel alloy. Its durability was phenomenal, and some Model Ts and their parts are in running order over a century later. Although Henry Ford resisted some kinds of change, he always championed the advancement of materials engineering, and often mechanical engineering and industrial engineering.

In 2002, Ford built a final batch of six Model Ts as part of their 2003 centenary celebrations. These cars were assembled from remaining new components and other parts produced from the original drawings. The last of the six was used for publicity purposes in the UK.

Although Ford no longer manufactures parts for the Model T, many parts are still manufactured through private companies as replicas to service the thousands of Model Ts still in operation today.

On May 26, 1927, Henry Ford and his son Edsel drove the 15-millionth Model T out of the factory.[16] This marked the famous automobile's official last day of production at the main factory.

Price and production

The moving assembly line system, which started on October 7, 1913, allowed Ford to reduce the price of his cars.[57] As he continued to fine-tune the system, Ford was able to keep reducing costs significantly.[58] As volume increased, he was able to also lower the prices due to some of the fixed costs being spread over a larger number of vehicles as large supply chain investments increased assets per vehicle. Other factors reduced the price such as material costs and design changes.[47]

In current equivalent dollars, the cost of the Runabout started at $23,476 in 1909 and bottomed out at $3,790 in 1925.

The figures below are US production numbers compiled by R.E. Houston, Ford Production Department, August 3, 1927. The figures between 1909 and 1920 are for Ford's fiscal year. From 1909 to 1913, the fiscal year was from October 1 to September 30 the following calendar year with the year number being the year in which it ended. For the 1914 fiscal year, the year was October 1, 1913, through July 31, 1914. Starting in August 1914, and through the end of the Model T era, the fiscal year was August 1 through July 31. Beginning with January 1920, the figures are for the calendar year.

| Year | Production | Price for Runabout | Current Equivalent Cost | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1909 | 10,666 | $825 | $23,476 | Touring car was $850. |

| 1910 | 19,050 | $900 | $24,695 | |

| 1911 | 34,858 | $680 | $18,659 | |

| 1912 | 68,773 | $590 | $15,631 | |

| 1913 | 170,211 | $525 | $13,581 | |

| 1914 | 202,667 | $440 | $11,231 | Fiscal year was only 10 months long due to change in end date from September 30 to July 31 |

| 1915 | 308,162 | $390 | $9,856 | |

| 1916 | 501,462 | $345 | $8,106 | [59] |

| 1917 | 735,020 | $500 | $9,978 | |

| 1918 | 664,076 | $500 | $8,499 | |

| 1919 | 498,342 | $500 | $7,373 | |

| 1920 | 941,042 | $395 | $5,041 | Production for fiscal year 1920, (August 1, 1919 through July 31, 1920). Price was $550 in March but dropped by September |

| 1920 | 463,451 | $395 | $5,041 | Production for balance of calendar year, August 1 through December 31. Total '1920' production (17 months) = 1,404,493 |

| 1921 | 971,610 | $325 | $4,659 | Price was $370 in June but dropped by September |

| 1922 | 1,301,067 | $319 | $4,873 | |

| 1923 | 2,011,125 | $364 | $5,462 | |

| 1924 | 1,922,048 | $265 | $3,953 | |

| 1925 | 1,911,705 | $260 | $3,790 | Touring car was $290 |

| 1926 | 1,554,465 | $360 | $5,199 | |

| 1927 | 399,725 | $360 | $5,299 | Production ended before mid-year to allow retooling for the Model A |

The above tally includes a total of 14,689,525 vehicles. Ford said the last Model T was the 15 millionth vehicle produced.[16]

Recycling

Henry Ford used wood scraps from the production of Model Ts to make charcoal briquettes. Originally named Ford Charcoal, the name was changed to Kingsford Charcoal after the Iron Mountain Ford Plant closed in 1951 and the Kingsford Chemical Company was formed and continued the wood distillation process. E. G. Kingsford, Ford's cousin by marriage, brokered the selection of the new sawmill and wood distillation plant site.[60] Lumber for production of the Model T came from the same location, built in 1920 called the Iron Mountain Ford which incorporated a sawmill where lumber from Ford purchased land in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan was cut and dried. Scrap wood was distilled at the Iron Mountain plant for its wood chemicals, with the end by product being lump charcoal. This lump charcoal was modified and pressed into briquettes and mass marketed by Ford.[61]

First global car

The Ford Model T was the first automobile built by various countries simultaneously, since they were being produced in Walkerville, Canada, and in Trafford Park, Greater Manchester, England, starting in 1911 and were later assembled in Germany, Argentina,[62] France, Spain, Denmark, Norway, Belgium, Brazil, Mexico, and Japan, as well as several locations throughout the US.[63] Ford made use of the knock-down kit concept almost from the beginning of the company as freight and production costs from Detroit had Ford assembling vehicles in major metropolitan centers of the US.

The Aeroford was an English automobile manufactured in Bayswater, London, from 1920 to 1925. It was a Model T with distinct hood and grille to make it appear to be a totally different design, what later would have been called badge engineering. The Aeroford sold from £288 in 1920, dropping to £168–214 by 1925. It was available as a two-seater, four-seater, or coupé.[64]

Advertising and marketing

Ford created a massive publicity machine in Detroit to ensure every newspaper carried stories and advertisements about the new product. Ford's network of local dealers made the car ubiquitous in virtually every city in North America. A large part of the success of Ford's Model T stems from the innovative strategy which introduced a large network of sales hubs making it easy to purchase the car.[12] As independent dealers, the franchises grew rich and publicized not just the Ford but the very concept of automobiling; local motor clubs sprang up to help new drivers and to explore the countryside. Ford was always eager to sell to farmers, who looked on the vehicle as a commercial device to help their business. Sales skyrocketed – several years posted around 100 percent gains on the previous year.

24 Hours of Le Mans

Parisian Ford dealer Charles Montier and his brother-in-law Albert Ouriou entered a heavily modified version of the Model T (the "Montier Special") in the first three 24 Hours of Le Mans.[65][66] They finished 14th in the inaugural 1923 race.[67]

Car clubs

Today, four main clubs exist to support the preservation and restoration of these cars: the Model T Ford Club International,[68] the Model T Ford Club of America[69] and the combined clubs of Australia. With many chapters of clubs around the world, the Model T Ford Club of Victoria[70] has a membership with a considerable number of uniquely Australian cars. (Australia produced its own car bodies, and therefore many differences occurred between the Australian bodied tourers[71] and the US/Canadian cars.) In the UK, the Model T Ford Register of Great Britain celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2010. Many steel Model T parts are still manufactured today, and even fiberglass replicas of their distinctive bodies are produced, which are popular for T-bucket style hot rods (as immortalized in the Jan and Dean surf music song "Bucket T", which was later recorded by The Who). In 1949, more than twenty years after the end of production, 200,000 Model Ts were registered in the United States.[72] In 2008, it was estimated that about 50,000 to 60,000 Ford Model Ts remain roadworthy.[73]

In popular media

- A 1920 Ford Model T is featured in the 1920 Harold Lloyd comedy short Get Out and Get Under.

- The Ford Model T was the car of choice for comedy duo Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy. It was used in most of their short and feature films.

- In 1966, Belgian comic book authors Maurice Tillieux and Francis created the comic adventures of a character named Marc Lebut and his Model T.

- The phrase to "go the way of the Tin Lizzie" is a colloquialism referring to the decline and elimination of a popular product, habit, belief, or behavior as a now outdated historical relic which has been replaced by something new.[74][75][76]

- In Aldous Huxley's Brave New World, Henry Ford is regarded as a messianic figure, Christian crosses have been truncated to Ts, and vehicles are called "flivvers" (from a slang reference to the Model T). Moreover, the calendar is converted to an A.F. ("After Ford") system, wherein the calendar begins (AF 1) with the introduction of the Model T (AD 1908). The well-known phrase God is in his heaven, all is right with the world (originating from Robert Browning's Pippa Passes) is changed into Ford is in his flivver, all is right with the world.

- The Model T has a featured role in the Walt Disney sci-fi comedy The Absent-Minded Professor, in which the classic car flies.

- In a 1964 episode of Hazel (TV series), sponsored by Ford and featuring the company's current models in the stories, Hazel acquires a 1920 Model T.

- Lizzie from the Cars franchise is based on a 1923 Ford Model T Coupe.[77]

- In the alternate history series Southern Victory by Harry Turtledove, the Model T was the most popular car in the United States before the Great War. It was so desirable that it was even exported to the Confederate States, which won the American Civil War in 1862. However, Model T's in the Confederacy proved difficult to maintain as none had been built locally. During the Great War, many Model T's served as Staff Cars for US generals and officers.

Gallery

Model T chronology

.jpg) 1909 Touring (a very early example with two-pedal, two-lever control)

1909 Touring (a very early example with two-pedal, two-lever control).jpg) 1909 Roadster

1909 Roadster 1909 Tourabout (like the Touring, but without rear doors)

1909 Tourabout (like the Touring, but without rear doors).jpg) 1911 Touring

1911 Touring.jpg) 1911 Torpedo Runabout

1911 Torpedo Runabout.jpg) 1911 Open Runabout

1911 Open Runabout- 1912 Touring

1912 Commercial Roadster

1912 Commercial Roadster.jpg) 1912 Torpedo Runabout

1912 Torpedo Runabout.jpg) 1912 Delivery Car

1912 Delivery Car.jpg) 1913 Touring

1913 Touring 1913 Runabout

1913 Runabout 1914 Touring

1914 Touring.jpg) 1914 Runabout

1914 Runabout 1915 Runabout – Note curved cowl panel

1915 Runabout – Note curved cowl panel- 1916 Touring

1917 Runabout – Note new curved hood matches cowl panel

1917 Runabout – Note new curved hood matches cowl panel 1919 Runabout

1919 Runabout 1920 Touring

1920 Touring 1921 Touring

1921 Touring.jpg) 1922 Runabout

1922 Runabout.jpg) 1922 flatbed truck

1922 flatbed truck 1923 Ford Model T Depot Hack

1923 Ford Model T Depot Hack 1923 Runabout (early '23 model)

1923 Runabout (early '23 model) 1924 Touring – Note higher hood and slightly shorter cowl panel – late '23 models were similar

1924 Touring – Note higher hood and slightly shorter cowl panel – late '23 models were similar.jpg) 1924–1925 Runabout

1924–1925 Runabout 1925 Touring – Note the balloon tires and split rims, optional extras of the period.

1925 Touring – Note the balloon tires and split rims, optional extras of the period. 1925 Touring

1925 Touring 1926 Runabout – Note higher hood and longer cowl panel

1926 Runabout – Note higher hood and longer cowl panel 1927 Runabout

1927 Runabout 1927 Touring – Last Ford Model T built at Highland Park Ford Plant

1927 Touring – Last Ford Model T built at Highland Park Ford Plant 1928 Ford Model A Tudor Sedan – Shown for comparison, note wider body and curved doors

1928 Ford Model A Tudor Sedan – Shown for comparison, note wider body and curved doors

See also

- New Zealand RM class (Model T Ford) – a 1925 experimental railcar based on a Model T powertrain

- Piper J-3 Cub, the 1930s/40s American light aircraft that developed a similar degree of ubiquity in general aviation circles to the Model T

- Lakeside Foundry

Notes

- Boyer, Mike (May 10, 1998). "Ford motored into Cincinnati long ago". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- "Ford Model T Plant". Cleveland Historical. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- Darbee, Jeff (July 2014). "City Quotient: I often smell something like vanilla cookies or cake when walking Downtown. Am I just hungry, or is that for real?". Columbus Monthly. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- "Ford Model T Assembly Building". MotorTexas. Retrieved August 4, 2015.

- Cherney, Bruce (March 14, 2013). "Ford of Canada plant — railway cars brought the parts that were assembled into complete vehicles". Winnipeg Real Estate News. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- "Ford's System of Branch Assembly Plants". Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- "Ford Model T 1908-1927". Carsized. Switzerland. Retrieved August 23, 2019.

- "Model T Facts" (Press release). US: Forid. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- Gordon, John Steele. "10 Moments That Made American Business". American Heritage (February/March 2007). Archived from the original on April 20, 2008. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- Price, R. G. (January 29, 2004). "Division of Labor, Assembly Line Thought – The Paradox of Democratic Capitalism". RationalRevolution.net. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- Cobb, James G. (December 24, 1999). "This Just In: Model T Gets Award". New York Times. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- Folkmann, Mads Nygaard (2011). "Encoding Symbolism: Immateriality and Possibility in Design". Design and Culture. 3 (1): 51–74. doi:10.2752/175470810X12863771378752.

- "Top 10 Best Selling Cars of All Time". Autoguide.com. Retrieved December 2, 2013.

- Curcio, Vincent (2013). Henry Ford. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195316926.

- "Chronicle of 1908". Library.thinkquest.org. 1908. Archived from the original on February 11, 2013. Retrieved October 21, 2012.

- "Henry Ford and the Model T". John Wiley & Sons. 1996. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Ritzinger, André. "Early Ford-models from the years 1903–1908". p. 5. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Hounshell, David A. (1984), From the American System to Mass Production, 1800–1932: The Development of Manufacturing Technology in the United States, Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0-8018-2975-8, LCCN 83016269, OCLC 1104810110

- Ford & Crowther 1922, p. 73.

- Domm, Robert W. (2009). Michigan Yesterday & Today. Minneapolis: Voyageur Press. ISBN 9781616731380.

- "University students compete to create 21st century Model T". Ford. Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

- "History Lesson: Hungary Celebrates the Ford Model T." India: Federation of Automobile Dealers Associations of India. February 27, 2006. Archived from the original on September 5, 2012. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Wik 1972.

- Clymer 1950, p. 100.

- Boggess, Trent E.; Patterson, Ronald (February 20, 2006). "The Model T Ignition Coil". US: Plymouth State College. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- "Model T Facts". Ford. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- English, Andrew (July 25, 2008). "Ford Model T reaches 100". The Telegraph. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Addison, Keith. "Ethanol fuel: Journey to Forever". Journey to Forever. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Kimes & Clark Jr. (1989), p. 551.

- "History of the Ford Motor Company – Fast Facts". The Frontenac Motor Company & The Ford Model T. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- Manly 1919, p. 268

- "Ford Model T Transmission". FordModelT.net. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- Pagé, Victor Wilfred (1917). The Model T Ford Car, Its Construction, Operation and Repair: A Complete Practical Treatise Explaining the Operating Principles of All Parts of the Ford Automobile, with Complete Instructions for Driving and Maintenance. Norman W. Henley Publishing Co. p. 241.

- Model T Ford Service. Ford.

- Ford & Crowther 1922, p. 72.

- McCalley 1994.

- Dutton 1942.

- Casey, Robert (2008). The Model T A Centennial History. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-8018-8850-2.

- "1926 Ford Model T Ice Saw". Owl's Head Transportation Museum. Retrieved December 24, 2012. Used for harvesting winter ice from ponds in Maine.

- Pripps & Morland 1993, p. 28.

- Leffingwell 2002, pp. 43–51.

- "Snowflyers Replace Dogs in Frozen North". Popular Mechanics (December): 878. 1934. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- "Model T Ford Forum: Forum 2011: Old Photo – Model T Rail Car". Model T Ford Club of America. 2011.

- "1926 Ford Model T Fire Truck – The Henry Ford". www.thehenryford.org. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- Killen, William D. (2008). Firefighting with Henry's Model T (1st ed.). Church Hill, TN: W.D. Killen. ISBN 9780615223032. OCLC 318191997.

- "North Charleston Fire Museum". www.northcharlestonfiremuseum.org. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- Abernathy, William J.; Wayne, Kenneth (September 1, 1974). "Limits of the Learning Curve". Harvard Business Review.

Ford’s objective was to reduce the price of the automobile and thereby increase volume and market share.

"Ford’s long devotion to the experience-curve strategy made the transition to another strategy difficult and very costly" (going from reducing Model T cost to increasing Model A price) "From the time it introduced the Model A, Ford was compelled to compete on the basis of product quality and performance — a strategy in which it was not skilled"

The rate of capital investment showed substantial increases after 1913, rising from 11 cents per sales dollar that year to 22 cents by 1921. The new facilities that were built or acquired included blast furnaces, logging operations and saw mills, a railroad, weaving mills, coke ovens, a paper mill, a glass plant, and a cement plant.

In its effort to keep reducing Model T costs while wages were rising, Ford continued to invest heavily in plant, property, and equipment. These facilities even included coal mines, rubber plantations, and forestry operations (to provide wooden car parts). By 1926, nearly 33 cents in such assets backed each dollar of sales, up from 20 cents just four years earlier, thereby increasing fixed costs and raising the break-even point. - Georgano 1985.

- Sandler, Martin (2003). Driving Around the USA: Automobiles in American Life. Oxford University Press. p. 21.

- Brinkley, Douglas (2003). Wheels for the world: Henry Ford, his company, and a century of progress, 1903–2003. Viking. p. 475.

- Sorensen, Charles E.; Lewis, David Lanier; Williamson, Samuel T. My forty years with Ford. Wayne State University Press. p. 4.

- "Last day of Model T production at Ford". History. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- "The Model T Ford". Frontenac Motor Company. Archived from the original on March 15, 2015. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- "Last Model T Produced in 1927". Cape Girardeau History and Photos. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- "Michigan History". Detroit News. Archived from the original on July 10, 2012.

- Wagner, Michael F. (2009). Domesticeringen af Ford i Danmark [The domestication of Ford in Denmark]. Denmark: Aalborg University. p. 14. Retrieved September 6, 2014.

Model T production in Denmark stopped in August 1927 for factory recondition.

- "Ford's Assembly Line Turns 100: How It Changed Manufacturing and Society". New York Daily News. October 7, 2013. Archived from the original on November 30, 2013. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- Cherif, Reda; Hasanov, Fuad; Pande, Aditya (May 22, 2017). "Riding the Energy Transition : Oil Beyond 2040". International Monetary Fund. p. 13. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

Vehicle adoption is strongly associated with the ability to offer an affordable price. The large fall in prices in the early 1900s, thanks to the economies of scale and process innovations made by Ford, is closely matched by a rise in motor vehicle registrations.

- $Lewis 1976, pp. 41–59.

- "Our Heritage". Kingsford. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Forstrom, Guy (Summer 2017). "The Burning History of the Charcoal Briquette". Historical Society of Michigan. 40 (2): 13–15.

- "Historia de Ford en Argentina" [History of Ford in Argentina] (in Spanish). Auto Historia. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- "Celebrating the Ford Model T, only 100 years young!". Auto Atlantic. 2008. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- David Culshaw & Peter Horrobin: The Complete Catalogue of British Cars 1895–1975. Veloce Publishing plc. Dorchester (1999). ISBN 1-874105-93-6

- Spurring, Quentin (2015). Le Mans 1923–29. Yeovil: Haynes Publishing. ISBN 978-1-91050-508-3.

- "Driver Database: Charles Montier". DriverDB.com.

- "1923 Le Mans 24 Hours | Motor Sport Magazine Database". Motor Sport.

- "The Model T Ford Club International". Modelt.org. Retrieved June 2, 2013.

- "Model T Ford Club of America". Mtfca.com. Retrieved June 2, 2013.

- "Model T Ford Club of Victoria". Modeltfordclubvic.org.au. Archived from the original on June 4, 2013. Retrieved June 2, 2013.

- "Model T Ford Australian Tourers". Model T Central. Retrieved June 2, 2013.

- Sedgwick 1972, pp. 50–51.

- Brooke, Lindsay (2008). Ford Model T: The Car that Put the World on Wheels. MBI Publishing Company. p. 188. ISBN 9780760327289.

- McColl, Catherine (2003). Happy as the Grass was Green: A Memoir. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 9781412216579.

- U.S. News & World Report, Volume 105 p. 52 (1988)

- Fernandez, Margot Biblical Literalism is Headed for a Showdown Which it Will Lose Examiner, March 30, 2011

- Disney Pixar's The World of Cars: Meet the Cars. Disney Press. 2008. p. 15. ISBN 978-142311925-8.

Bibliography

- Clymer, Floyd (1955). "Henry's wonderful Model T, 1908–1927". New York, NY, U.S.: McGraw-Hill. LCCN 55010405. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Clymer, Floyd (1950). "Treasury of Early American Automobiles, 1877–1925". New York, NY, U.S.: McGraw-Hill. LCCN 50010680. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Dutton, William S. (1942), Du Pont: One Hundred and Forty Years, Charles Scribner's Sons, LCCN 42011897.

- Ford, Henry; Crowther, Samuel (1922), My Life and Work, Garden City, New York, USA: Garden City Publishing Company, Inc. Various republications, including ISBN 9781406500189. Original is public domain in U.S. Also available at Google Books.

- Georgano, G. N. (1985). "Cars: Early and Vintage, 1886–1930". London, UK: Grange-Universal. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Hounshell, David A. (1984), From the American System to Mass Production, 1800–1932: The Development of Manufacturing Technology in the United States, Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0-8018-2975-8, LCCN 83016269, OCLC 1104810110

- Kimes, Beverly Rae; Clark Jr., Henry Austin (1989). Standard Catalog of America Cars: 1805–1942 (2nd ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 9780873411110.

- Lacey, Robert (1986). Ford: The Men and the Machine. Boston, MA, U.S.: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-51166-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leffingwell, Randy (2002) [1998], Ford Tractors, Borders, ISBN 0-681-87878-9.

- Lewis, David (1976). The Public Image of Henry Ford: An American Folk Hero and His Company. Detroit, MI, U.S.: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-1553-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Manly, Harold P. (1919). The Ford Motor Car and Truck; Fordson Tractor: Their Construction, Care and Operation. Chicago, IL, USA: Frederick J. Drake & Co.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McCalley, Bruce W. (1994). Model T Ford: The Car That Changed the World. Iola, WI, U.S.: Krause Publications. ISBN 0-87341-293-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pripps, Robert N.; Morland, Andrew (photographer) (1993). Farmall Tractors: History of International McCormick-Deering Farmall Tractors. Farm Tractor Color History Series. Osceola, WI, U.S.: MBI. ISBN 978-0-87938-763-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reynolds, David (2009). America, Empire of Liberty: A New History of the United States. Basic Books. ISBN 978-1-84614-056-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ross, Irwin (November 1974). "Ford's Fabulous Flivver". Gas Engine Magazine. Retrieved August 11, 2016.

- Sedgwick, Michael (1972) [1962]. Early Cars. Octopus Books. ISBN 0-7064-0058-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ward, Ian, ed. (1974). "The World of Automobiles". 13. London, UK: Orbis. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Wik, Reynold M. (1972). Henry Ford and Grass-Roots America. Ann Arbor, MI, U.S.: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-97200-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ford Model T. |

- FordModelT.net – Resource for Model T Owners and Enthusiasts

- Model T Ford Club of America (USA)

- Model T Ford Club International

- Ford Model T at the Internet Movie Cars Database

- First and second web pages of Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome's vintage vehicle collection, featuring five Model T-based vehicles