Pyrene

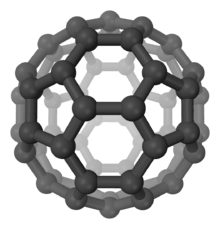

Pyrene is a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) consisting of four fused benzene rings, resulting in a flat aromatic system. The chemical formula is C

16H

10. This yellow solid is the smallest peri-fused PAH (one where the rings are fused through more than one face). Pyrene forms during incomplete combustion of organic compounds.

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Pyrene | |

| Other names

Benzo[def]phenanthrene | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| 1307225 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.004.481 |

| 84203 | |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C16H10 | |

| Molar mass | 202.256 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | colorless solid

(yellow impurities are often found at trace levels in many samples). |

| Density | 1.271 g/mL |

| Melting point | 145 to 148 °C (293 to 298 °F; 418 to 421 K) |

| Boiling point | 404 °C (759 °F; 677 K) |

| 0.135 mg/L | |

| -147.9·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | irritant |

| R-phrases (outdated) | 36/37/38-45-53 |

| S-phrases (outdated) | 24/25-26-36 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | non-flammable |

| Related compounds | |

Related PAHs |

benzopyrene |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Occurrence and properties

Pyrene was first isolated from coal tar, where it occurs up to 2% by weight. As a peri-fused PAH, pyrene is much more resonance-stabilized than its five-member-ring containing isomer fluoranthene. Therefore, it is produced in a wide range of combustion conditions. For example, automobiles produce about 1 μg/km.[1]

Reactions

Oxidation with chromate affords perinaphthenone and then naphthalene-1,4,5,8-tetracarboxylic acid. It undergoes a series of hydrogenation reactions, and it is susceptible to halogenation, Diels-Alder additions, and nitration, all with varying degrees of selectivity.[1] Bromination occurs at one of the 3-positions.[2]

Photophysics

Pyrene and its derivatives are used commercially to make dyes and dye precursors, for example pyranine and naphthalene-1,4,5,8-tetracarboxylic acid. It has strong absorbance in UV-Vis in three sharp bands at 330 nm in DCM. The emission is close to the absorption, but moving at 375 nm.[3] The morphology of the signals change with the solvent. Its derivatives are also valuable molecular probes via fluorescence spectroscopy, having a high quantum yield and lifetime (0.65 and 410 nanoseconds, respectively, in ethanol at 293 K). Pyrene was the first molecule for which excimer behavior was discovered.[4] Such excimer appears around 450 nm. Theodor Förster reported this in 1954.[5]

Applications

Pyrene's fluorescence emission spectrum is very sensitive to solvent polarity, so pyrene has been used as a probe to determine solvent environments. This is due to its excited state having a different, non-planar structure than the ground state. Certain emission bands are unaffected, but others vary in intensity due to the strength of interaction with a solvent.

Although it is not as problematic as benzopyrene, animal studies have shown pyrene is toxic to the kidneys and liver. It is now known that pyrene affects several living functions in fish and algae.[7][8][9][10]

Experiments in pigs show that urinary 1-hydroxypyrene is a metabolite of pyrene, when given orally.[11]

Pyrenes are strong electron donor materials and can be combined with several materials in order to make electron donor-acceptor systems which can be used in energy conversion and light harvesting applications.[3]

References

- Senkan, Selim and Castaldi, Marco (2003) "Combustion" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim.

- Gumprecht, W. H. (1968). "3-Bromopyrene". Org. Synth. 48: 30. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.048.0030.

- Tagmatarchis, Nikos; Ewels, Christopher P.; Bittencourt, Carla; Arenal, Raul; Pelaez-Fernandez, Mario; Sayed-Ahmad-Baraza, Yuman; Canton-Vitoria, Ruben (2017-06-05). "Functionalization of MoS 2 with 1,2-dithiolanes: toward donor-acceptor nanohybrids for energy conversion". NPJ 2D Materials and Applications. 1 (1): 13. doi:10.1038/s41699-017-0012-8. ISSN 2397-7132.

- Van Dyke, David A.; Pryor, Brian A.; Smith, Philip G.; Topp, Michael R. (May 1998). "Nanosecond Time-Resolved Fluorescence Spectroscopy in the Physical Chemistry Laboratory: Formation of the Pyrene Excimer in Solution". Journal of Chemical Education. 75 (5): 615. doi:10.1021/ed075p615.

- Förster, Th.; Kasper, K. (June 1954). "Ein Konzentrationsumschlag der Fluoreszenz". Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie. 1 (5_6): 275–277. doi:10.1524/zpch.1954.1.5_6.275.

- Pham, Tuan Anh; Song, Fei; Nguyen, Manh-Thuong; Stöhr, Meike (2014). "Self-assembly of pyrene derivatives on Au(111): Substituent effects on intermolecular interactions". Chem. Commun. 50 (91): 14089. doi:10.1039/C4CC02753A. PMID 24905327.

- Oliveira, M.; Ribeiro, A.; Hylland, K.; Guilhermino, L. (2013). "Single and combined effects of microplastics and pyrene on juveniles (0+ group) of the common goby Pomatoschistus microps (Teleostei, Gobiidae)". Ecological Indicators. 34: 641–647. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2013.06.019.

- Oliveira, M.; Gravato, C.; Guilhermino, L. (2012). "Acute toxic effects of pyrene on Pomatoschistus microps (Teleostei, Gobiidae): Mortality, biomarkers and swimming performance". Ecological Indicators. 19: 206–214. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2011.08.006.

- Oliveira, M.; Ribeiro, A.; Guilhermino, L. (2012). "Effects of exposure to microplastics and PAHs on microalgae Rhodomonas baltica and Tetraselmis chuii". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 163: S19–S20. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.05.062.

- Oliveira, M.; Ribeiro, A.; Guilhermino, L. (2012). "Effects of short-term exposure to microplastics and pyrene on Pomatoschistus microps (Teleostei, Gobiidae)". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 163: S20. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.05.063.

- Keimig, S. D.; Kirby, K. W.; Morgan, D. P.; Keiser, J. E.; Hubert, T. D. (1983). "Identification of 1-hydroxypyrene as a major metabolite of pyrene in pig urine". Xenobiotica. 13 (7): 415–20. doi:10.3109/00498258309052279. PMID 6659544.

Further reading

- Birks, J. B. (1969). Photophysics of Aromatic Molecules. London: Wiley.

- Valeur, B. (2002). Molecular Fluorescence: Principles and Applications. New York: Wiley-VCH.

- Birks, J. B. (1975). "Excimers". Reports on Progress in Physics. 38 (8): 903–974. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/38/8/001. ISSN 0034-4885.

- Fetzer, J. C. (2000). The Chemistry and Analysis of the Large Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. New York: Wiley.