Governor-General of India

The Governor-General of India (from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 1947, the representative of the Indian head of state. The office was created in 1773, with the title of ‘Governor-general of the Presidency of Fort William’. The officer had direct control only over Fort William, but supervised other East India Company officials in India. Complete authority over all of British India was granted in 1833, and the official came to be known as the "governor-general of India".

| Viceroy and Governor-General of India | |

|---|---|

.svg.png) Standard in the British Raj (1885–1947) | |

.svg.png) Flag in the Dominion of India (1947–1950) | |

Lord Mountbatten Last Viceroy of British Raj  Chakravarti Rajagopalachari Last Governor-General of Dominion of India | |

| Style | His Excellency |

| Residence | Government House (1858–1931) Viceroy's House (1931–1950) Viceregal Lodge (1888–1947) |

| Appointer |

|

| Formation | 20 October 1774 |

| First holder | Warren Hastings |

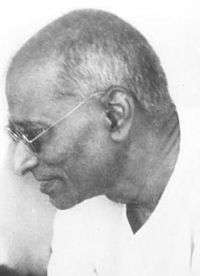

| Final holder | Chakravarthi Rajagopalachari |

| Abolished | 26 January 1950 |

In 1858, as a consequence of the Indian Rebellion the previous year, the territories and assets of the East India Company came under the direct control of the British Crown; as a consequence the Company Raj was succeeded by the British Raj. The Governor-General (now also the Viceroy) headed the central government of India, which administered the provinces of British India, including the Punjab, Bengal, Bombay, Madras, the United Provinces, and others.[1] However, much of India was not ruled directly by the British Government; outside the provinces of British India, there were hundreds of nominally independent princely states or "native states", whose relationship was not with the British Government or the United Kingdom, but rather one of homage directly with the British Monarch as sovereign successor to the Mughal Emperors. From 1858, to reflect the Governor-General's new additional role as the Monarch's representative in re the fealty relationships vis the princely states, the additional title of Viceroy was granted, such that the new office was entitled "viceroy and governor-general of India". This was usually shortened to "viceroy of India".

The title of viceroy was abandoned when British India split into the two independent dominions of India and Pakistan, but the office of governor-general continued to exist in each country separately—until they adopted republican constitutions in 1950 and 1956, respectively.

Until 1858, the governor-general was selected by the Court of Directors of the East India Company, to whom he was responsible. Thereafter, he was appointed by the sovereign on the advice of the British Government; the secretary of state for India, a member of the UK Cabinet, was responsible for instructing him or her on the exercise of their powers. After 1947, the sovereign continued to appoint the governor-general, but thereafter did so on the advice of the newly-sovereign Indian Government.

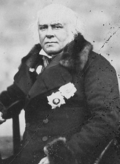

Governors-general served at the pleasure of the sovereign, though the practice was to have them serve five-year terms. Governors-general could have their commission rescinded; and if one was removed, or left, a provisional governor-general was sometimes appointed until a new holder of the office could be chosen. The first governor-general in India was Warren Hastings, the first official governor-general of British India was Lord William Bentinck, and the first governor-general of the Dominion of India was Lord Mountbatten.

History

Many parts of the Indian subcontinent were governed by the East India Company, which nominally acted as the agent of the Mughal emperor. In 1773, motivated by corruption in the Company, the British government assumed partial control over the governance of India with the passage of the Regulating Act of 1773. A governor-general and Supreme Council of Bengal were appointed to rule over the Presidency of Fort William in Bengal. The first governor-general and Council were named in the Act.

The Charter Act 1833 replaced the governor-general and Council of Fort William with the governor-general and Council of India. The power to elect the governor-general was retained by the Court of Directors, but the choice became subject to the sovereign's approval.

After the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the East India Company's territories in India were put under the direct control of the sovereign. The Government of India Act 1858 vested the power to appoint the governor-general in the sovereign. The governor-general, in turn, had the power to appoint all lieutenant governors in India, subject to the sovereign's approval.

India and Pakistan acquired independence in 1947, but governors-general continued to be appointed over each nation until republican constitutions were written. Louis Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma, remained governor-general of India for some time after independence, but the two nations were otherwise headed by native governors-general. India became a secular republic in 1950; Pakistan became an Islamic one in 1956.

Functions

The governor-general originally had power only over the Presidency of Fort William in Bengal. The Regulating Act, however, granted them additional powers relating to foreign affairs and defence. The other presidencies of the East India Company (Madras, Bombay and Bencoolen) were not allowed to declare war on or make peace with an Indian prince without receiving the prior approval of the governor-general and Council of Fort William.

The powers of the governor-general, in respect of foreign affairs, were increased by the India Act 1784. The Act provided that the other governors under the East India Company could not declare war, make peace or conclude a treaty with an Indian prince unless expressly directed to do so by the governor-general or by the Company's Court of Directors.

While the governor-general thus became the controller of foreign policy in India, he was not the explicit head of British India. That status came only with the Charter Act 1833, which granted him "superintendence, direction and control of the whole civil and military Government" of all of British India. The Act also granted legislative powers to the governor-general and Council.

After 1858, the governor-general (now usually known as the viceroy) functioned as the chief administrator of India and as the Sovereign's representative. India was divided into numerous provinces, each under the head of a governor, lieutenant governor or chief commissioner or administrator. Governors were appointed by the British Government, to whom they were directly responsible; lieutenant governors, chief commissioners, and administrators, however, were appointed by and were subordinate to the viceroy. The viceroy also oversaw the most powerful princely rulers: the Nizam of Hyderabad, the Maharaja of Mysore, the Maharaja (Scindia) of Gwalior, the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir and the Gaekwad (Gaekwar) Maharaja of Baroda. The remaining princely rulers were overseen either by the Rajputana Agency and Central India Agency, which were headed by representatives of the viceroy, or by provincial authorities.

The Chamber of Princes was an institution established in 1920 by a Royal Proclamation of King-Emperor George V to provide a forum in which the princely rulers could voice their needs and aspirations to the government. The chamber usually met only once a year, with the viceroy presiding, but it appointed a Standing Committee, which met more often.

Upon independence in August 1947, the title of viceroy was abolished. The representative of the British Sovereign became known once again as the governor-general. C. Rajagopalachari became the only Indian governor-general. However, once India acquired independence, the governor-general's role became almost entirely ceremonial, with power being exercised on a day-to-day basis by the Indian cabinet. After the nation became a republic in 1950, the president of India continued to perform the same functions.

Council

The governor-general was always advised by a Council on the exercise of his legislative and executive powers. The governor-general, while exercising many functions, was referred to as the "Governor-General in Council."

The Regulating Act 1773 provided for the election of four counsellors by the East India Company's Court of Directors. The governor-general had a vote along with the counsellors, but he also had an additional vote to break ties. The decision of the Council was binding on the governor-general.

In 1784, the Council was reduced to three members; the governor-general continued to have both an ordinary vote and a casting vote. In 1786, the power of the governor-general was increased even further, as Council decisions ceased to be binding.

The Charter Act 1833 made further changes to the structure of the Council. The Act was the first law to distinguish between the executive and legislative responsibilities of the governor-general. As provided under the Act, there were to be four members of the Council elected by the Court of Directors. The first three members were permitted to participate on all occasions, but the fourth member was only allowed to sit and vote when legislation was being debated.

In 1858, the Court of Directors ceased to have the power to elect members of the Council. Instead, the one member who had a vote only on legislative questions came to be appointed by the sovereign, and the other three members by the secretary of state for India.

The Indian Councils Act 1861 made several changes to the Council's composition. Three members were to be appointed by the secretary of state for India, and two by the Sovereign. The power to appoint all five members passed to the Crown in 1869. The viceroy was empowered to appoint an additional six to twelve members (changed to ten to sixteen in 1892, and to sixty in 1909). The five individuals appointed by the sovereign or the Indian secretary headed the executive departments, while those appointed by the viceroy debated and voted on legislation.

In 1919, an Indian legislature, consisting of a Council of State and a Legislative Assembly, took over the legislative functions of the Viceroy's Council. The viceroy nonetheless retained significant power over legislation. He could authorise the expenditure of money without the Legislature's consent for "ecclesiastical, political [and] defense" purposes, and for any purpose during "emergencies." He was permitted to veto, or even stop debate on, any bill. If he recommended the passage of a bill, but only one chamber cooperated, he could declare the bill passed over the objections of the other chamber. The Legislature had no authority over foreign affairs and defence. The president of the Council of State was appointed by the viceroy; the Legislative Assembly elected its president, but the election required the viceroy's approval.

Style and title

Until 1833, the title of the position was "governor-general of Bengal". The Government of India Act 1833 converted the title into "governor-general of India". The title "viceroy and governor-general" was first used in the queen's proclamation appointing Viscount Canning in 1858.[3] It was never conferred by an act of parliament, but was used in warrants of precedence and in the statutes of knightly orders. In usage, "viceroy" is employed where the governor-general's position as the monarch's representative is in view.[4] The viceregal title was not used when the sovereign was present in India. It was meant to indicate new responsibilities, especially ritualistic ones, but it conferred no new statutory authority. The governor-general regularly used the title in communications with the Imperial Legislative Council, but all legislation was made only in the name of the Governor-General-in-Council (or the Government of India).[5]

The governor-general was styled Excellency and enjoyed precedence over all other government officials in India. He was referred to as 'His Excellency' and addressed as 'Your Excellency'. From 1858 to 1947, the Governor-General was known as the Viceroy of India (from the French roi, meaning 'king'), and wives of Viceroys were known as Vicereines (from the French reine, meaning 'queen'). The Vicereine was referred to as 'Her Excellency' and was also addressed as 'Your Excellency'. Neither title was employed while the Sovereign was in India. However, the only British sovereign to visit India during the period of British rule was George V, who attended the Delhi Durbar in 1911 with his wife, Mary.

When the Order of the Star of India was founded in 1861, the viceroy was made its grand master ex officio. The viceroy was also made the ex officio grand master of the Order of the Indian Empire upon its foundation in 1877.

Most governors-general and viceroys were peers. Frequently, a viceroy who was already a peer would be granted a peerage of higher rank, as with the granting of a marquessate to Lord Reading and an earldom and later a marquessate to Freeman Freeman-Thomas. Of those viceroys who were not peers, Sir John Shore was a baronet, and Lord William Bentinck was entitled to the courtesy title 'lord' because he was the son of a duke. Only the first and last governors-general – Warren Hastings and Chakravarti Rajagopalachari – as well as some provisional governors-general, had no honorific titles at all.

Flag and Insignia

From around 1885, the Viceroy of India was allowed to fly a Union Flag augmented in the centre with the 'Star of India' surmounted by a Crown. This flag was not the Viceroy's personal flag; it was also used by Governors, Lieutenant Governors, Chief Commissioners and other British officers in India. When at sea, only the Viceroy flew the flag from the mainmast, while other officials flew it from the foremast.

From 1947 to 1950, the Governor-General of India used a dark blue flag bearing the royal crest (a lion standing on the Crown), beneath which was the word 'India' in gold majuscules. The same design is still used by many other Commonwealth Realm Governors-General. This last flag was the personal flag of the Governor-General only.

Badge of the Viceroy and Governor-General (1885–1947)

Badge of the Viceroy and Governor-General (1885–1947).svg.png) Standard of the Viceroy and Governor-general (1885–1947)

Standard of the Viceroy and Governor-general (1885–1947).svg.png) Standard of the Governor-General (1947–50)

Standard of the Governor-General (1947–50)

Residence

The governor-general of Fort William resided in Belvedere House, Calcutta, until the early nineteenth century, when Government House was constructed. In 1854, the lieutenant governor of Bengal took up residence there. Now, the Belvedere Estate houses the National Library of India.

Lord Wellesley, who is reputed to have said that ‘India should be governed from a palace, not from a country house’, constructed a grand mansion, known as Government House, between 1799 and 1803. The mansion remained in use until the capital moved from Calcutta to Delhi in 1912. Thereafter, the lieutenant governor of Bengal, who had hitherto resided in Belvedere House, was upgraded to a full governor and transferred to Government House. Now, it serves as the residence of the governor of the Indian state of West Bengal, and is referred to by its Bengali name Raj Bhavan.

After the capital moved from Calcutta to Delhi, the viceroy occupied the newly built Viceroy's House, designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens. Though construction began in 1912, it did not conclude until 1929; the palace was not formally inaugurated until 1931. The final cost exceeded £877,000 (over £35,000,000 in modern terms)—more than twice the figure originally allocated. Today the residence, now known by the Hindi name of 'Rashtrapati Bhavan', is used by the president of India.

Throughout the British administration, governors-general retreated to the Viceregal Lodge (now Rashtrapati Niwas) at Shimla each summer to escape the heat, and the government of India moved with them. The Viceregal Lodge now houses the Indian Institute of Advanced Study.

List

| Portrait | Name | Term | Appointer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before 1773 the Governor General of the Presidency of Fort William was named as Governor of Bengal (1757–1772). | ||||

| Governors General of the Presidency of Fort William (1773–1833) | ||||

|

Warren Hastings[nb 1] | 20 October 1773 |

8 February 1785 |

East India Company (1773–1858) |

_by_anonymous_(circa_1772-1792).jpg) |

John Macpherson (acting) |

8 February 1785 |

12 September 1786 | |

|

Charles Cornwallis, The Marquess Cornwallis[nb 2] |

12 September 1786 |

28 October 1793 | |

|

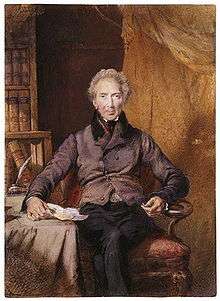

John Shore | 28 October 1793 |

18 March 1798 | |

|

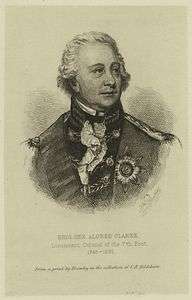

Alured Clarke (acting) |

18 March 1798 |

18 May 1798 | |

| Richard Wellesley, Earl of Mornington[nb 3] |

18 May 1798 |

30 July 1805 | ||

|

The Marquess Cornwallis | 30 July 1805 |

5 October 1805 | |

|

Sir George Barlow, Bt (acting) |

10 October 1805 |

31 July 1807 | |

|

The Lord Minto | 31 July 1807 |

4 October 1813 | |

.jpg) |

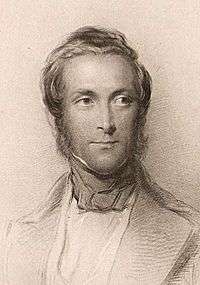

Francis Rawdon-Hastings, 1st Marquess of Hastings[nb 4] |

4 October 1813 |

9 January 1823 | |

|

John Adam (acting) |

9 January 1823 |

1 August 1823 | |

|

The Lord Amherst[nb 5] | 1 August 1823 |

13 March 1828 | |

|

William Butterworth Bayley (acting) |

13 March 1828 |

4 July 1828 | |

| Governors-General of India (1833–1858) | ||||

|

Lord William Bentinck | 4 July 1828 |

20 March 1835 |

East India Company (1773–1858) |

|

Charles Metcalfe, Bt (acting) |

20 March 1835 |

4 March 1836 | |

|

The Lord Auckland[nb 6] | 4 March 1836 |

28 February 1842 | |

|

The Lord Ellenborough | 28 February 1842 |

June 1844 | |

|

William Wilberforce Bird (acting) |

June 1844 |

23 July 1844 | |

|

Henry Hardinge[nb 7] | 23 July 1844 |

12 January 1848 | |

|

The Earl of Dalhousie[nb 8] | 12 January 1848 |

28 February 1856 | |

|

The Viscount Canning[nb 9] | 28 February 1856 |

31 October 1858 | |

| Viceroys and Governors-General of India (1858–1947) | ||||

|

The Viscount Canning[nb 10] | 1 November 1858 |

21 March 1862 |

Victoria.svg.png) (1837–1901) |

|

The Earl of Elgin | 21 March 1862 |

20 November 1863 | |

|

Robert Napier (acting) |

21 November 1863 |

2 December 1863 | |

|

William Denison (acting) |

2 December 1863 |

12 January 1864 | |

|

Sir John Lawrence, Bt | 12 January 1864 |

12 January 1869 | |

|

The Earl of Mayo | 12 January 1869 |

8 February 1872 | |

|

Sir John Strachey (acting) |

9 February 1872 |

23 February 1872 | |

|

The Lord Napier (acting) |

24 February 1872 |

3 May 1872 | |

|

The Lord Northbrook | 3 May 1872 |

12 April 1876 | |

|

The Lord Lytton | 12 April 1876 |

8 June 1880 | |

|

The Marquess of Ripon | 8 June 1880 |

13 December 1884 | |

|

The Earl of Dufferin | 13 December 1884 |

10 December 1888 | |

|

The Marquess of Lansdowne | 10 December 1888 |

11 October 1894 | |

|

The Earl of Elgin | 11 October 1894 |

6 January 1899 | |

|

The Lord Curzon of Kedleston[nb 11] | 6 January 1899 |

18 November 1905 | |

|

The Earl of Minto | 18 November 1905 |

23 November 1910 |

Edward VII.svg.png) (1901–1910) |

|

The Lord Hardinge of Penshurst | 23 November 1910 |

4 April 1916 |

George V.svg.png) (1910–1936) |

|

The Lord Chelmsford | 4 April 1916 |

2 April 1921 | |

|

The Earl of Reading | 2 April 1921 |

3 April 1926 | |

|

The Lord Irwin | 3 April 1926 |

18 April 1931 | |

|

The Earl of Willingdon | 18 April 1931 |

18 April 1936 | |

|

The Marquess of Linlithgow | 18 April 1936 |

1 October 1943 |

Edward VIII.svg.png) (1936) |

|

The Viscount Wavell | 1 October 1943 |

21 February 1947 |

George VI.svg.png) (1936–1952) |

|

The Viscount Mountbatten of Burma | 21 February 1947 |

15 August 1947 | |

| Governors-General of the Dominion of India (1947–1950) | ||||

|

The Viscount Mountbatten of Burma[nb 12] | 15 August 1947 |

21 June 1948 |

George VI.svg.png) (1936–1952) |

|

Chakravarti Rajagopalachari | 21 June 1948 |

26 January 1950 | |

See also

Notes

- Originally joined on 28 April 1772

- Earl Cornwallis from 1762; created Marquess Cornwallis in 1792.

- Created Marquess Wellesley in 1799.

- Earl of Moira prior to being created Marquess of Hastings in 1816

- Created Earl Amherst in 1826.

- Created Earl of Auckland in 1839.

- Created Viscount Hardinge in 1846.

- Created Marquess of Dalhousie in 1849.

- Created Earl Canning in 1859.

- Created Earl Canning in 1859.

- The Lord Ampthill was acting Governor-General in 1904

- Created Earl Mountbatten of Burma on 28 October 1947.

References

- The term British India is mistakenly used to mean the same as the British Indian Empire, which included both the provinces and the Native States.

- "Imperial Impressions". Hindustan Times. 20 July 2011. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012.

- Queen Victoria's Proclamation

- H. Verney Lovett, "The Indian Governments, 1858–1918", The Cambridge History of the British Empire, Volume V: The Indian Empire, 1858–1918 (Cambridge University Press, 1932), p. 226.

- Arnold P. Kaminsky, The India Office, 1880–1910 (Greenwood Press, 1986), p. 126.

External links

- Association of Commonwealth Archivists and Record Managers (1999) "Government Buildings – India"

- Forrest, G. W., CIE, (editor) (1910) Selections from the State Papers of the Governors-General of India; Warren Hastings (2 vols), Oxford: Blackwell's

- Encyclopædia Britannica ("British Empire" and "Viceroy"), London: Cambridge University Press, 1911, 11th edition,

- James, Lawrence (1997) Raj: the Making and Unmaking of British India London: Little, Brown & Company ISBN 0-316-64072-7

- Keith, A. B. (editor) (1922) Speeches and Documents on Indian Policy, 1750–1921, London: Oxford University Press

- Oldenburg, P. (2004). "India." Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia. (Archived 2009-10-31)

- mountbattenofburma.com – Tribute & Memorial website to Louis, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Governors-General of India. |

- Arnold, Sir Edwin (1865). The Marquis of Dalhousie's Administration of British India: Annexation of Pegu, Nagpor, and Oudh, and a general review of Lord Dalhousie's rule in India. Saunders, Otley, and Company.

- Dodwell H. H., ed. The Cambridge History of India. Volume 6: The Indian Empire 1858-1918. With Chapters on the Development of Administration 1818-1858 (1932) 660pp online edition; also published as vol 5 of the Cambridge History of the British Empire

- Moon, Penderel. The British Conquest and Dominion of India (2 vol. 1989) 1235pp; the fullest scholarly history of political and military events from a British top-down perspective;

- Rudhra, A. B. (1940) The Viceroy and Governor-General of India. London: H. Milford, Oxford University Press

- Spear, Percival (1990) [First published 1965], A History of India, Volume 2, New Delhi and London: Penguin Books. Pp. 298, ISBN 978-0-14-013836-8.

.svg.png)